Abstract

Background

This study presents a framework for determining the allocation and distribution of the limited amount of vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Methods

After analyzing the pandemic strategies of the major organizations and countries and with a literature review conducted by a core panel, a modified Delphi survey was administered to 13 experts in the fields of vaccination, infectious disease, and public health in the Republic of Korea. The following topics were discussed: 1) identifying the objectives of the vaccination strategy, 2) identifying allocation criteria, and 3) establishing a step-by-step vaccination framework and prioritization strategy based on the allocation criteria. Two rounds of surveys were conducted for each topic, with a structured questionnaire provided via e-mail in the first round. After analyzing the responses, a meeting with the experts was held to obtain consensus on how to prioritize the population groups.

Results

The first objective of the vaccination strategy was maintenance of the integrity of the healthcare system and critical infrastructure, followed by reduction of morbidity and mortality and reduction of community transmission. In the initial phase, older adult residents in care homes, high-risk health and social care workers, and personal support workers who work in direct contact with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients would be prioritized. Expansion of vaccine supply would allow immunization of older adults not included in phase 1, followed by healthcare workers not previously included and individuals with comorbidities. Further widespread vaccine supply would ensure availability to the extended adult age groups (50–64 years old), critical workers outside the health sector, residents who cannot socially distance, and, eventually, the remaining populations.

Conclusion

This survey provides the much needed insight into the decision-making process for vaccine allocation at the national level. However, flexibility in adapting to strategies will be essential, as new information is constantly emerging.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccines, Policy, Distribution, Survey, Korea

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has infected over 130 million people globally, resulting in 2,842,325 deaths as of April 4, 2021.1 To achieve a protection threshold in the population, 67% of people would have to develop natural immunity.2 Despite the increased number of infections, this seems difficult to attain, as studies in the United States (US) reported low rates of patients with antibodies to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (< 24%), even after the large wave in the winter.3 Similarly, poor results were reported in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) (1.0–8.5%)4,5 and the Republic of Korea (< 1.0%).6,7 Thus, it seems that vaccination is necessary to reach the protective threshold.

As of April 2, 2021, 28 vaccine candidates entered phase 3 of clinical trials.8 It is expected that 74% of phase 3 vaccines will be approved.9 Nevertheless, an initial limitation in the supply is expected because of manufacturing issues. The crucial question arising is who gets first access to vaccines when they become available.

During the previous H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009, many countries (including Republic of Korea) applied step-by-step strategies according to vaccine supply. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in the US has steadily updated guidelines on allocating and targeting vaccines during influenza pandemics.10,11 Currently, these principles have informed the ACIP's strategy concerning the COVID-19 vaccination. However, the SARS-CoV-2 is remarkably different from influenza, and new vaccine allocation protocols are necessary.

Unlike the 2009 pandemic, the incidence or severity of COVID-19 infection is relatively low in children and adolescents, and severe morbidity and mortality are prevalent in the older population. Transmission-related risk groups are also difficult to clearly define.12,13 Thus, considering the characteristics of COVID-19 known to date, the major organizations and countries, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), US, and United Kingdom (UK), suggest allocating the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines to healthcare personnel and populations at high risk of severe morbidity and mortality, such as older persons and persons with comorbidities.14,15,16 However, the range or ranking of each target population has not yet been specified in most countries, and the inclusion of high-exposure occupations varies between countries. The detailed strategy of each country should be based on its own situations, such as epidemiology, financial status, public acceptance, and availability of vaccine doses.

During the study period, it was not known which vaccines would be approved, although the minimum criteria for approval recommended by the WHO were presented,17 and the priority would vary depending on the characteristics of vaccines to be developed. Nevertheless, at this point, a draft of the preliminary strategy for allocation of the COVID-19 vaccine reflecting the domestic situation was necessary for vaccine introduction. The present study discusses and proposes foundational objects and outlines a framework for the allocation of COVID-19 vaccines in the Republic of Korea.

METHODS

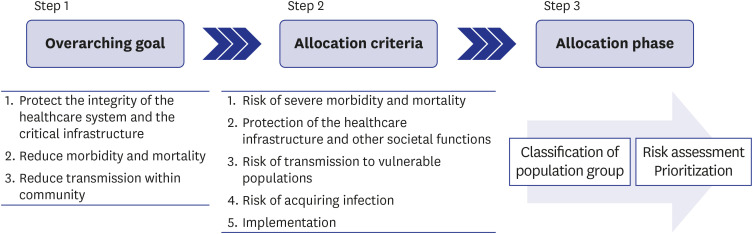

In the present study, three topics were discussed to create a framework for the allocation and prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination: 1) identifying the objectives of the vaccination strategy, 2) identifying the allocation criteria, and 3) establishing a step-by-step vaccination framework and prioritization strategy based on allocation criteria (Fig. 1). To manage the task, two panels were convened: a core panel and an expert panel. The core panel, consisting of 6 researchers, was the strategic steering group that oversaw the task. The modified Delphi technique was used, where the core panel collected updated data and background evidence, provided a structured questionnaire, hosted online meetings, and gathered expert opinions. The expert panel consisted of 13 relevant experts. This study was conducted from July 23, 2020, to October 31, 2020. Specifically, the survey on the first topic was carried out from August 11, 2020, to August 21, 2020; on the second topic, from August 21, 2020, to September 21, 2020; and, on the last topic, from September 21, 2020 to October 31, 2020 based on the previous surveys. During this period, the vaccination strategies of several organizations and countries were being updated.18,19,20,21,22,23 By referencing these standards and with an additional systematic review,15,24,25 the panels devised a strategy suitable for the domestic situation. The process was as follows:

Fig. 1. Process of creating a framework for allocation and prioritization of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination.

First, the core panels reviewed previous pandemic and vaccine strategies of major organizations and countries, assessed the progress of vaccine development, and prepared background evidence reports for each topic. Second, the standards were selected from representative frameworks and modified for the Korean situation. The core panel created and provided a structured questionnaire using the modified evidence. Third, expert opinions were gathered through several rounds of the modified Delphi technique. Fourth, the framework was completed through expert consensus and revision by the core panel. As the time period required to obtain enough vaccines was not known, the researchers considered the initial supply of vaccine to be tightly constrained, enough for only approximately 3–5% of the Korean population.18,26 Since vaccine supply would be phased incrementally with increasing supply, the researchers planned to list target groups according to how the vaccine would be secured in approximately 5 phases.

Research design

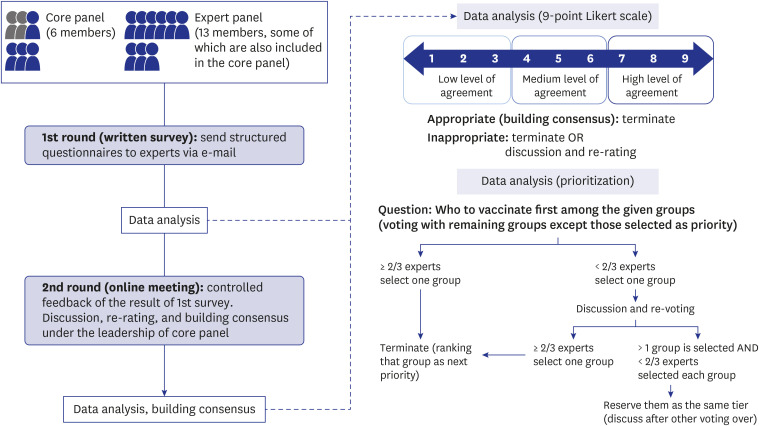

Two rounds of surveys were conducted for each topic, and a structured questionnaire was provided via e-mail in the first round. The questionnaire comprised close-ended questions (e.g., scoring level of consent, risk assessment) and open-ended questions. After the first round, the core panel calculated the aggregate ratings and summarized the comments. The responses to the open-ended questions in the first round were reflected in the second questionnaire after a discussion within the core panel. The second round of surveying was conducted through online meetings, where the results of the first round of the survey were shared and expert consensus was reached through discussion and voting (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Process of building consensus (the modified Delphi consensus process).

Data analysis

Expert opinions on the objectives, allocation criteria, and classification of the population group were mainly collected in the form of consensus. The experts answered the items in the structured questionnaire using a 9-point Likert scale, and the results were summed. If ≥ 30% of the experts rated an item in the lower third (ratings 1–3) and ≥ 30% rated it in the upper third (ratings 7–9), it was considered a “disagreement.” We regarded quality criteria with an overall median rating of 7 to 9, without disagreement, as “appropriate” or “building consensus.” We considered criteria with a median rating of 1 to 6 as “inappropriate” or “failed to reach consensus.” The criteria that elicited disagreement were considered “inappropriate.”27 During the second round of the survey, the results of the first survey were discussed and re-voted on. If the result of a certain question was still “inappropriate” in the second round, the question was eliminated or re-voting was held through discussion.

Prioritization was identified using a slightly different method. In the first round, each target population group was rated on a 5-point scale based on the allocation criteria. The mean and standard deviation of the ratings for each population group were calculated separately for each criterion. Using this result as a reference, the ranking of each group was determined in the second round of the survey. The ranking was carried out to determine the group that ranked first among the remaining population groups (Fig. 2). When two-thirds of the experts selected a certain group, it was considered as “building consensus.” If less than two-thirds agreed, re-voting was conducted after sufficient discussion. If consensus was still not reached after the second vote, the decision was withheld and discussed again after all rankings were made to determine their ranking or to classify them in the same tier. Since it was important to determine the ranking in the context of limited vaccine supply, only the rankings corresponding to 50–60% of the total population were discussed. After listing them from first to last, the target groups to be vaccinated in 5 phases were listed in a step-by-step manner.

RESULTS

Participants

The expert panel consisted of 13 experts representing the relevant associations/societies: 3 experts each from the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, Korean Vaccine Society, Korean Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, and Korean Society of Epidemiology and 1 expert from the National Central Clinical Committee.

Step 1: Identifying the objectives of the vaccination strategy

All members of the expert panel responded to the first and second rounds of the survey to set the objectives of vaccination. All experts showed a high level of agreement with the inclusion of all the items in the questionnaire (Table 1). After a discussion in the second round, the inclusion objectives were ranked according to their level of agreement (mean score on the 9-point Likert scale). The most prioritized objective was to “protect the integrity of the healthcare system and critical infrastructure,” followed by “reduction in morbidity and mortality” and “prevention of transmission within community.”

Table 1. Identifying objectives of vaccination.

| Item | Agreement among 13 experts (mean scores on 9-point Likert scale) | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Protect the integrity of the healthcare system and the critical infrastructure | High level of agreement and appropriateness (8.6) | 1 |

| Reduce morbidity and mortality | High level of agreement and appropriateness (8) | 2 |

| Reduce transmission within community | High level of agreement and appropriateness (7.5) | 3 |

Step 2: Identifying allocation criteria

All members of the expert panel responded to the first and second rounds of the survey. In the first round, all items in the questionnaire were considered appropriate for inclusion in the allocation criteria (Table 2). Based on the items selected in the first round, the experts were asked to rate the relative importance of each item on a scale of 1 (least importance) to 5 (absolutely necessary) in the second round to rank the items. The rankings are presented in Table 2. The risks of severe morbidity and mortality were the highest priority, followed by protection of healthcare infrastructure and other societal functions, risk of transmission to vulnerable populations, and risk of acquiring infection. Implementation was ranked the lowest, and equity considerations were excluded from the criteria.

Table 2. Allocation criteria.

| Criteria candidate | Round 1: Rating | Round 2: Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of severe morbidity and mortality | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 1 |

| Protection of healthcare infrastructure and other societal functions | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 2 |

| Risk of transmission to vulnerable populations | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 3 |

| Implementation | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 5 |

| Risk of acquiring infection | 7.5 ± 2.2 | 4 |

| Equity considerations | 6.0 ± 2.8 | Exclude |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation not otherwise specified.

Step 3: Establishing a step-by-step vaccination framework and prioritization strategy based on the allocation criteria

Category of and estimated number in the population group

The framework for allocating and targeting the initial vaccination of certain groups included a structure that classified the population into 4 broad categories corresponding to the objectives of the vaccination program: 1) providing healthcare and community support, 2) providing COVID-19-related support, 3) maintaining critical infrastructure, and 4) the general population. These 4 categories covered the entire population. Each of these categories further included specific subpopulations defined by occupation, age, health status, or place of residence. The categories, population groups, and estimated numbers for each group are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Category, population group, and estimated number of each population group.

| Category | Population group | Estimated number (% of total populationa) | Reference or relevant instituteb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health care and community support services | High risk workers in healthcare facilities, workers in long-term care facilities/home welfare facilities | 1,395,000 (2.7) | MOHW, data obtained from HIRA |

| Other healthcare workers | |||

| COVID-19 support services | First responders (patient management, isolation, epidemiological investigation, quarantine), emergency medical technicians | 92,000 (0.2) | Local municipalities, KNFA |

| Other critical infrastructure | Police, firefighters, soldiers | 745,000 (1.4) | KNPA, KNFA, MND |

| Critical infrastructure workers who are indispensable for the public to maintain daily life (e.g., energy and water supply, transportation system) | 159,900 (0.3) | K-water, MOTIE, MOLIT | |

| General population | Infants & children (0–6 years) | 2,614,420 (5.0) | Statistics Korea43 |

| Elementary school aged children (7–12 year) | 2,827,468 (5.5) | ||

| Middle and high school aged children (13–18 year) | 2,849,595 (5.5) | ||

| Adults 19–49 years old | 22,663,859 (43.7) | ||

| Adults 50–64 years old | 12,525,494 (24.2) | ||

| Older adults (≥65 years old) | 8,359,117 (16.1) | ||

| Adults aged 19–64 years old with significant comorbid conditions | 6,026,894 (12.1) | Data obtained from HIRAc | |

| Adults aged 19–64 years old with moderate comorbid conditions | 5,647,911 (11.4) | ||

| Older adults in congregated or overcrowded settingsd | 566,400 (1.1) | Data obtained from HIRA | |

| Persons in congregated or overcrowded setting (except older adults)e | 63,927 (0.1) | Statistics of MOHW44 | |

| Child/adolescent education facility workers and staff | 675,000 (1.3) | Statistics of MOE45 | |

| Incarcerated/detained people and staff | 19,570 (0.04) | MOJ | |

| Pregnant women | 295,000 (0.6) | Data obtained from HIRA | |

| Household contacts of older adults or people with comorbid conditions | Not available |

MOHW = Ministry of Health and Welfare, KNFA = Korean National Fire Agency, KNPA = Korean National Police Agency, MND = Ministry of National Defense, K-water = Korea Water Resource Corporation, MOTIE = Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, MOLIT = Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs, MOE = Ministry of Education, HIRA = Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, MOJ = Ministry of Justice.

aCalculation based on the total population reported to Statistics Korea as of August 2020. The results extracted from the health insurance claims data were based on the total population of the data source. Owing to overlapping cases, the total proportion exceeded 100%; bThe number of population groups was estimated through relevant reference or by direct request to a relevant institute (unpublished data); cSince the amount of vaccines would be limited, the number of individuals with comorbidities that put them at higher risk was estimated by dividing them into significant and moderate groups, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classification as of September 2020.34 The number of individuals with significant or moderate comorbidity was estimated using Korean claims data (from April 2019 to May 2020); dThis includes residents of healthcare and non-healthcare congregate settings (e.g., group homes, long-term care facilities); eCenters for children; single parents; disabled people; mental health patients; people with unstable housing, tuberculosis, and Hansen's disease; and women's shelters.

Round 1: Scores for each group based on allocation criteria

All members of the expert panel responded to the first round of the survey and rated each population group on a 5-point scale based on the allocation criteria. Table 4 outlines the means and standard deviations of the scores given by the 13 experts for each population group.

Table 4. Score of each target population based on allocation criteria (results based on opinions of 13 experts).

| Target population | Risk of severe morbidity and mortality | Protection of social function | Risk of transmission to vulnerable populations | Risk of acquiring infection | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk healthcare workers | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| Other healthcare workers | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.9 |

| COVID-19 support services | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.7 |

| Police, firefighters, soldiers | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.2 |

| Other critical workersa | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.8 |

| Preschool children (0–6 years) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.8 |

| Elementary school age (7–12 years) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| Middle/high school age (13–18 years) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.9 |

| Adults (19–49 years) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

| Adults (50–64 years) | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.9 |

| Older adults (≥ 65 years) | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 0.8 |

| Older adults residing in care homes | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Adults with significant comorbidity | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

| Adults with moderate comorbidity | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.9 |

| People in group homes (except older adults) | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.9 |

| Teachers and relevant staff | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.8 |

| Incarcerated/detained people and staff | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.0 |

| Pregnancy | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 1.2 |

| Close contacts of older adults or people with comorbid conditions | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

Each population group was rated on a 5-point scale based on the allocation criteria: 1 (least importance) to 5 (absolute importance). The mean values of the 13 experts' opinions are indicated. Based on the mean value, the 5-point scale was divided into 3 equal parts and marked in different colors: 1 to 2.3 points, white (low score); above 2.3 and less than 3.6, light orange (medium score); and above 3.6, dark orange (high score). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 5-point scale.

aCritical infrastructure workers who are indispensable for the public to maintain daily life (e.g., energy and water supply, transportation system).

Based on the average score, the 5-point scale was divided into 3 sections, marked in different colors, referred to as low, medium, and high scores. Healthcare workers, individuals working in COVID-19 support services, and older adults in congregated or overcrowded settings received high scores on ≥ 3 criteria. The remaining older adults, individuals with comorbid conditions, and the group comprising police officers, firefighters, and soldiers received medium-to-high scores on more than half of the criteria. Household contacts with older adults or people with comorbidities and other critical workers had high scores in one criterion (the risk of transmission to vulnerable populations and protection of social function, respectively), but overall low scores in other criteria.

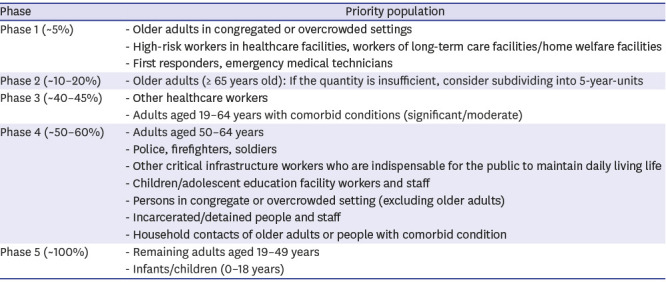

Round 2: Prioritization and establishment of a vaccination framework

Using the results of Round 1 as a reference, each group was ranked by voting in the second round of the survey (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). Ten to eleven experts (77–85%) participated in the second round. Six votes were used to rank the population groups. Since an increase in vaccine production over time was expected, the remaining half of the population that was not ranked by voting was largely divided into 2 groups (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Considering the voting results and rankings, estimated population numbers, and vaccine amount-securing scenarios, Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 1 show the framework of the vaccine allocation strategy in 5 phases.

Table 5. Framework of the allocation and prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination according to expected vaccine availability.

| Phase | Priority population |

|---|---|

| Phase 1 (~5%) | - Older adults in congregated or overcrowded settings |

| - High-risk workers in healthcare facilities, workers of long-term care facilities/home welfare facilities | |

| - First responders, emergency medical technicians | |

| Phase 2 (~10–20%) | - Older adults (≥ 65 years old): If the quantity is insufficient, consider subdividing into 5-year-units |

| Phase 3 (~40–45%) | - Other healthcare workers |

| - Adults aged 19–64 years with comorbid conditions (significant/moderate) | |

| Phase 4 (~50–60%) | - Adults aged 50–64 years |

| - Police, firefighters, soldiers | |

| - Other critical infrastructure workers who are indispensable for the public to maintain daily living life | |

| - Children/adolescent education facility workers and staff | |

| - Persons in congregate or overcrowded setting (excluding older adults) | |

| - Incarcerated/detained people and staff | |

| - Household contacts of older adults or people with comorbid condition | |

| Phase 5 (~100%) | - Remaining adults aged 19–49 years |

| - Infants/children (0–18 years) |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Older adult residents in care homes and high-risk health and social care workers (in terms of risk of transmission to vulnerable persons and acquiring infection) would be given the top priority. It was difficult to determine how to prioritize the 2 groups even after several discussions. As they comprise only less than 5% of the total population, the 2 groups were jointly ranked first. Another group included in the first phase was COVID-19 support workers (first responders, emergency medical technicians), as they had a similar level of risk as the high-risk health and social care workers in the first-round survey.

In phase 2, all older adults not included in phase 1 were included. Considering the incidence of COVID-19 infection across different ages in the Republic of Korea,13 older adults were defined as those aged ≥ 65 years. However, if the amount of vaccine doses was insufficient, this group could be further subdivided into 5-year intervals and considered for vaccination, starting from the older age group.

In phase 3, expansion of vaccine supply would allow for the immunization of another cohort of individuals with comorbid conditions and healthcare workers not included in phase 1. Adults aged 50–64 years might be considered as an alternative to those with comorbidity due to the high proportion of comorbid conditions among them28 and for improved implementation. Nevertheless, individuals with comorbid conditions had clear benefits of vaccination in terms of the risk of severe morbidity and mortality29; therefore, it was decided that they had to be given high priority.

In phase 4, the vaccine supply would become widely available and allow broader immunization. Since the severity of COVID-19 is found to increase in patients aged 50 years and over in the Republic of Korea, adults aged 50–64 years were placed under this phase. Individuals at high risk of exposure due to occupation or place of residence and critical infrastructure workers outside the healthcare sector were included in this phase. In addition, despite the possible difficulties in implementation, people living with older adults or those with comorbidities were recommended to get vaccinated in this phase.

Finally, once vaccine supply becomes widely available (phase 5), vaccines would be made available to children and healthy young adults. An important issue here is that broad immunization of children would depend on whether new COVID-19 vaccines are adequately tested for safety and efficacy in those age groups.

DISCUSSION

This study proposed pandemic frameworks for COVID-19 vaccine allocation by organizing a Delphi survey of experts from the fields of vaccination, infectious disease, and public health in the Republic of Korea. The results of this survey are in line with those of previous reports that focused on initially reducing mortality and protecting the health system.18,19,23,30 Reduction of transmission was also a fundamental objective, but this approach was difficult to apply initially for the following reasons. First, any substantial impact of vaccination on reducing transmission would require a mass of individuals to be vaccinated. In the early phase, there would not be a sufficient amount of vaccines available for this effective transmission-focused strategy. Moreover, ongoing vaccine trials have not been designed to estimate the impact on transmission, and evidence of such an impact might not be available for some time after approval. Furthermore, considering the lack of data on transmission risk groups, it is important to focus on a reasonable group that will clearly benefit from vaccination at the start of the vaccination program.

To achieve the goal of reducing mortality and protecting the health system, the WHO and COVAX facilities included the following groups as reasonable targets for Tier 1: frontline workers in health and social care settings, people over the age of 65 years, and people who have underlying comorbidities that put them at higher risk of death.14,30 Similar priority groups were proposed in Europe, the UK, Canada, and Australia.31,32,33,34 The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) and Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) also suggested similar concepts but especially emphasized high-risk individuals among health and social care workers (in terms of risk of transmission to vulnerable persons and acquiring infection) and older adults in congregate settings.18,34 Thus, the possible priority groups presented in this study are similar to those prioritized by major countries or institutions. Among these priority groups, people with comorbid conditions were divided into two groups (significant and moderate) in this study, as they accounted for a quarter of the total population. However, the evidence used to classify them is still insufficient. In the framework suggested by the NASEM, those with two or more high-risk comorbidities were classified as having significant risk, while those with only one were classified as having moderate risk.18 In the present study, significant- and moderate-risk comorbidities were temporarily classified according to the level of evidence presented by the Centers for Disease Control.35 This classification may change continuously as data are collected, and the classification itself may be meaningless if sufficient amounts of vaccine doses are secured at once.

In this study, the ranking of pregnant women was not discussed. Because pregnancy is one of the possible conditions that puts women at high risk,35 the ranking needs to be reviewed as soon as the vaccine efficacy and safety data are collected. In addition, the ranking of children and adolescents was low because of the low mortality rate in this group.36 Although data are still limited, this group could be meaningful as a transmission source, as with influenza, and the vaccination of this group could be significant in terms of resumption of education and reducing outbreaks in the population.37 The ranking of this group will be reviewed as soon as more information is collected.

The framework presented in this study was based on the evidence and epidemiological situation as of October 31, 2020. There was a lack of certainty about the characteristics of COVID-19 vaccines that could become available in the Republic of Korea, and gaps remain in the scientific knowledge of the virus and disease. Because a range of uncertain factors may affect the implementation of the framework, these results should be interpreted cautiously, and it is necessary to consider various scenarios in advance. First, the vaccination strategy against COVID-19 will ultimately be guided by the available vaccines and the outcomes against which each vaccine will provide protection. If the efficacy is inferior in older adults or people with comorbidities, changes in the framework of the priority target group should be considered. It would be helpful to perform mathematical modeling of whether individuals in the priority groups in the framework should still be offered vaccination if the vaccine is less efficacious for these groups. The actual efficacy is also affected by how well people adhere to the basic non-pharmaceutical interventions; therefore, appropriate public health messages and education emphasizing such interventions are necessary. Another important issue is vaccine safety. Knowledge about vaccine safety from clinical trials is limited. Monitoring the side effects and adjusting the allocation framework are necessary steps to minimize safety concerns. Transparent communication with the public about the risks and benefits of vaccines is crucial. Before moving on to the next step in ranking, it would be necessary to make the best effort to vaccinate all prioritized populations. There may also be a scenario in which several vaccines with different characteristics are concomitantly approved. For the best results, available information should be gathered to determine the optimal vaccine for each target group. When multiple vaccines are used, the importance of monitoring efficacy and safety must be re-emphasized. The severity of the outbreak will also influence vaccine allocation. If the pandemic is severe and a substantial number of people are infected, the maintenance of social infrastructure may become a more important objective, and, in this case, critical infrastructure workers outside the health sector as well as all healthcare workers might take priority. In addition, the route and frequency of administration; stability in storage and transportation for each vaccine; and social, economic, and legal aspects may also affect the implementation of the framework.

During the study period, data on the characteristics of each vaccine were scarce. Since November 2020, phase 3 results of representative vaccine candidates were released,38,39,40 and some vaccines were approved and widely administered. The recently published results of Phase 3 clinical trials, which focused on the prevention of symptomatic COVID-19 infection, showed substantially higher efficacy than the minimal recommendation of the WHO,17 with some vaccines reportedly having more than 90% efficacy. However, vaccine efficacy is considerably decreased depending on the variant strains, highlighting the need for monitoring of circulating strains at the time of administration. Some vaccines showed similar efficacy in older adults,38,39 while others have not yet been analyzed among older adults.41,42 Persons with comorbidities were usually included, but immunocompromised or pregnant women were not included in most studies, and there were scarce data on children. Vaccination plans and strategies need to be adapted as more information becomes available. For this, high-quality surveillance and adequate modeling capacities should be emphasized.

This study presented a framework for allocation and distribution decisions related to scarce SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. While reaching consensus, the members of the expert panel used information available as of October 31, 2020, to identify priority groups. Flexibility in adapting strategies is essential, especially as new information is emerging almost every day, which could influence our assessment of priority groups. Although the final decision on vaccine allocation must also take into account national policies on the type and amount of vaccine supply, public acceptability, epidemiologic consideration, equity, and other factors, this survey provides much needed insight into the decision-making process for vaccine allocation at the national level. Furthermore, the process presented here may assist policymakers in other countries by providing guidance on how to allocate the COVID-19 vaccine, at least in the initial stages of deployment.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (grant number 2020-E2405-00).

Disclosure: The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this article do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

- Conceptualization: Peck KR, Cheong HJ, Kim SI.

- Data curation: Choi MJ, Choi WS, Seong H.

- Formal analysis: Choi MJ, Choi WS.

- Investigation: Choi MJ, Choi WS, Seong H.

- Methodology: Choi MJ, Choi WS, Lee H.

- Software: Choi JY, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Cho EY, Kim DH, Park H, Lee H, Kim NJ, Song JY.

- Validation: Choi MJ, Choi WS, Seong H, Cheong HJ, Kim SI, Peck KR.

- Writing - original draft: Choi MJ, Choi WS.

- Writing - review & editing: Peck KR, Kim SI, Cheong HJ, Park H, Kim YJ.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

The result of the second round of surveys to reach consensus on priorities

Prioritization of each target population

Vaccination phases and population groups

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 6 April 2021. [Updated April 4, 2021]. [Accessed April 6, 2021]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---6-april-2021.

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the EU/EEA and the UK – eighth update. 8 April 2020. [Updated April 8, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-rapid-risk-assessment-coronavirus-disease-2019-eighth-update-8-april-2020.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Nationwide commercial laboratory seroprevalence survey. [Accessed March 2, 2021]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#national-lab.

- 4.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Immune responses and immunity to SARS-CoV-2. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/latest-evidence/immune-responses.

- 5.Rostami A, Sepidarkish M, Leeflang MM, Riahi SM, Nourollahpour Shiadeh M, Esfandyari S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(3):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. [Updated November 23, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?brdId=&brdGubun=&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=361276&contSeq=361276&board_id=140&gubun=BDJ.

- 7.Noh JY, Seo YB, Yoon JG, Seong H, Hyun H, Lee J, et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among outpatients in southwestern Seoul, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(33):e311. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Draft landscape and tracker of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. [Updated April 2, 2021]. [Accessed April 4, 2021]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines.

- 9.Thomas DW, Burns J, Audette J, Carroll A, Dow-Hygelund C, Hay M. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim updated planning guidance on allocating and targeting pandemic influenza vaccine during an influenza pandemic. [Accessed March 2, 2021]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/national-strategy/planning-guidance/index.html.

- 11.Kim WJ. Development of policy and strategy for novel influenza A (H1N1) vaccination. [Updated 2010]. [Accessed December 6, 2020]. https://scienceon.kisti.re.kr/srch/selectPORSrchReport.do?cn=TRKO201300000256.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by age group. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed December 6, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html.

- 13.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Occurrence status of COVID-19 in South Korea. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed December 6, 2020]. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/bdBoardList_Real.do?brdId=1&brdGubun=11&ncvContSeq=&contSeq=&board_id=&gubun.

- 14.World Health Organization. A global framework to ensure equitable and fair allocation of COVID-19 products and potential implication for COVID-19 vaccines. WHO Member States Briefing. [Updated June 18, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.ccghr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Global-Allocation-Framework.pdf.

- 15.Mbaeyi S ACIP COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group. Considerations for COVID-19 vaccine prioritization. [Updated June 24, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-06/COVID-08-Mbaey-508.pdf.

- 16.Independent report. Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation: interim advice on priority groups for covid-19 vaccination. [Updated June 18, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi/interim-advice-on-priority-groups-for-covid-19-vaccination.

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO target product profiles for COVID-19 vaccines. [Updated April 9, 2020]. [Accessed February 14, 2021]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-target-product-profiles-for-covid-19-vaccines.

- 18.Gayle H, Foege W, Brown L, Kahn B. Framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 2, 2021]. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25917/framework-for-equitable-allocation-of-covid-19-vaccine.

- 19.Independent report. JCVI: updated interim advice on priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination. [Updated September 25, 2020]. [Accessed February 11, 2021]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi-25-september-2020/jcvi-updated-interim-advice-on-priority-groups-for-covid-19-vaccination.

- 20.Oliver S ACIP COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group. Overview of vaccine equity and prioritization frameworks. [Updated September 22, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-09/COVID-06-Oliver-508.pdf.

- 21.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Key aspects regarding the introduction and prioritisation of COVID-19 vaccination in the EU/EEA and the UK. [Updated October 26, 2020]. [Accessed February 11, 2021]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/key-aspects-regarding-introduction-and-prioritisation-covid-19-vaccination.

- 22.Toner E, Barnill A, Krubiner C, Bernstein J, Privor-Dumm L, Watson M. Interim Framework for COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation and Distribution in the United States. Baltimore, MD, USA: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; [Updated August 2020]. [Accessed March 2, 2021]. https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/publications/interim-framework-for-covid-19-vaccine-allocation-and-distribution-in-the-us. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. WHO SAGE values framework for the allocation and prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination. [Updated September 14, 2020]. [Accessed March 2, 2021]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-sage-values-framework-for-the-allocation-and-prioritization-of-covid-19-vaccination.

- 24.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccines. [Updated July 13, 2009]. [Accessed February 7, 2021]. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_vaccine_20090713/en/

- 25.Mbaeyi S ACIP COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group. COVID-19 vaccine prioritization: work group considerations. [Update July 29, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-07/COVID-07-Mbaeyi-508.pdf.

- 26.Dooling K ACIP COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group. COVID-19 vaccine prioritization: work group considerations. [Updated August 26, 2020]. [Accessed November 29, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-08/COVID-08-Dooling.pdf.

- 27.Kim SY, Choi MY, Shin SS, Ji SM, Park JJ, Yoo JH, et al. NECA's Handbook for Clinical Practice Guideline Development. Seoul, Korea: National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi MJ, Song JY, Noh JY, Yoon JG, Lee SN, Heo JY, et al. Disease burden of hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in South Korea: Analysis based on age and underlying medical conditions. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(44):e8429. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji W, Huh K, Kang M, Hong J, Bae GH, Lee R, et al. Effect of underlying comorbidities on the infection and severity of COVID-19 in Korea: a nationwide case-control study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(25):e237. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Fair allocation mechanism for COVID-19 vaccines through the COVAX Facility. Final working version. [Updated September 9, 2020]. [Accessed March 2, 2021]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/fair-allocation-mechanism-for-covid-19-vaccines-through-the-covax-facility.

- 31.European Commission. EU vaccines strategy. [Accessed February 12, 2021]. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/public-health/coronavirus-vaccines-strategy_en.

- 32.Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) Preliminary advice on general principles to guide the prioritisation of target populations in a COVID-19 vaccination program in Australia. [Updated November 13, 2020]. [Accessed February 12, 2021]. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/atagi-preliminary-advice-on-general-principles-to-guide-the-prioritisation-of-target-populations-in-a-covid-19-vaccination-program-in-australia.

- 33.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) Guidance on the prioritization of initial doses of COVID-19 vaccine(s) [Accessed February 12, 2021]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-prioritization-initial-doses-covid-19-vaccines.html.

- 34.Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) Independent report. Priority groups for coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination: advice from the JCVI, 30 December 2020. [Update December 30, 2020]. [Accessed February 12, 2021]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi-30-december-2020.

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19, people at increased risk and other people who need to take extra precautions. [Accessed October 30, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/index.html.

- 36.Sung HK, Kim JY, Heo J, Seo H, Jang YS, Kim H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 3,060 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea, January–May 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(30):e280. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viboud C, Boëlle PY, Cauchemez S, Lavenu A, Valleron AJ, Flahault A, et al. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(506):684–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The first interim data analysis of the Sputnik V vaccine against COVID-19 phase III clinical trials in the Russian Federation demonstrated 92% efficacy [press release] [Updated November 11, 2020]. [Accessed February 14, 2021]. https://sputnikvaccine.com/newsroom/pressreleases/the-first-interim-data-analysis-of-the-sputnik-v-vaccine-against-covid-19-phase-iii-clinical-trials-/

- 42.Novavax. Novavax COVID-19 vaccine demonstrates 89.3% efficacy in UK phase 3 trial [press release] [Updated January 29, 2021]. [Accessed February 14, 2021]. https://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-demonstrates-893-efficacy-uk-phase-3.

- 43.Statistics Korea. Population sector. [Accessed February 11, 2021]. https://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsListIndex.do?menuId=M_01_01&vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parmTabId=M_01_01&outLink=Y&entrType=#A11_2015_1_10_10.6.

- 44.Ministry of Health and Welfare, Social Welfare Facility Information System. The status of facility residents. [Accessed October 27, 2020]. http://www.w4c.go.kr/intro/introFcltInmtSttus.do.

- 45.Ministry of Education. Kindergarten, elementary, middle, and high school education statistics for 2020. [Accessed October 27, 2020]. https://kess.kedi.re.kr/index.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The result of the second round of surveys to reach consensus on priorities

Prioritization of each target population

Vaccination phases and population groups