Abstract

This cross-sectional study assesses compliance within a random sample of hospitals with a federal rule requiring hospitals to disclose the prices they negotiate with insurers.

In the US, hospital prices vary widely but are not visible to patients or the public. In 2019, the federal government finalized a rule requiring hospitals to disclose the prices they negotiate with insurers.1 The rule—which survived legal challenges from hospitals—took effect on January 1, 2021, and includes 2 new major requirements.2 First, for all services, hospitals must publish discounted cash prices (applicable to uninsured patients) and payer-specific negotiated rates. Second, hospitals must display price data, including expected out-of-pocket costs, for “shoppable services” that can be scheduled in advance (eg, office visits) in a consumer-friendly manner that facilitates service-specific comparisons across hospitals (eg, price estimator tools).3

Although price-shopping by patients is limited even when prices are observable, transparency could lower prices through other means.4,5 However, compliance could be limited because the penalties for noncompliance are minimal (maximum $300 per day) and the costs of disclosure potentially great. We assessed early compliance with the new requirements.

Methods

We analyzed a random sample of 100 (out of 6171) hospitals and the 100 hospitals with highest gross revenue in 2017.6 We examined highest-revenue hospitals because the administrative costs of compliance should be inconsequential, but the repercussions of disclosure may be greater. For each hospital, we determined whether a machine-readable file with charge data and a separate tool for shoppable services were available. For the file, we assessed whether payer-specific negotiated rates and discounted cash prices were included. For shoppable services, we examined whether patients’ health insurance information was required to access hospital rates for that insurer. Data acquisition and analysis were conducted from March 1 through 10, 2021. The Harvard Medical School Committee on Human Studies determined that the study was not research on human participants.

Results

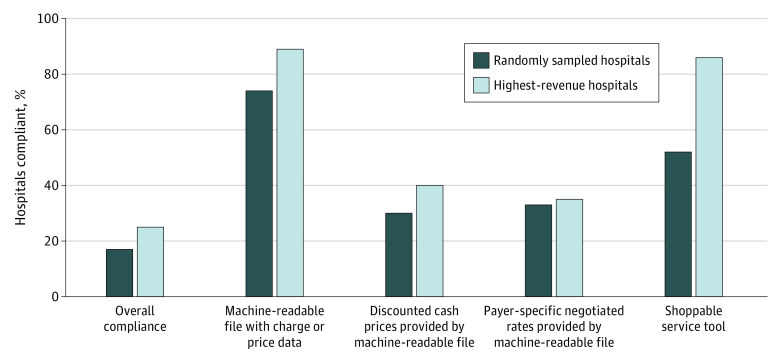

The Table lists the characteristics of the hospitals. Of the 100 randomly sampled hospitals, 83 (83%; 95% CI, 74%-90%) were noncompliant with at least 1 major requirement (Figure). Only 33 reported payer-specific negotiated rates, and 30 reported discounted cash prices in a machine-readable file.

Table. Hospital Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. | Mean | Hospitals, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of beds | Total annual discharges | Gross revenue (millions), $ | Rural | Critical access | Teaching | ||

| Randomly sampled hospitals | 100 | 147 | 7077 | 808 | 44 | 22 | 64 |

| Highest-revenue hospitals | 100 | 837 | 42 170 | 7006 | 8 | 0 | 96 |

Source: Hospital Cost Report Public Use File from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6

Figure. Compliance With US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Price Transparency Rule Among US Hospitals.

Shoppable service tool refers to whether a consumer-friendly display of shoppable services (eg, price estimator) was available.

A total of 52 hospitals offered a price estimator tool for shoppable services, of which 23 (44.2%) posted payer-specific negotiated rates in a machine-readable file. All price estimator tools required personal health plan information to access price or cost-sharing information; discounted cash prices could be viewed without plan information since they are not insurer-specific.

Of the 100 highest-revenue hospitals, 75 (75%; 95% CI, 65%-83%) were noncompliant with at least 1 requirement (Figure). Only 35 reported payer-specific negotiated rates, and 40 reported discounted cash prices in a machine-readable file. A total of 86 offered a price estimator tool, of which 34 (39.5%) posted payer-specific negotiated rates in a machine-readable file.

Discussion

As of March 2021, a small proportion of US hospitals were compliant with the major requirements of the new federal rule requiring disclosure of negotiated prices. Hospitals exhibited selectively higher compliance with the requirement of a price estimator for patients to view personalized out-of-pocket costs for shoppable services; a smaller proportion made their data fully accessible to the public by posting a machine-readable file with payer-specific negotiated rates.

Selective compliance was especially pronounced for the 100 highest-revenue hospitals, a low proportion of which fully disclosed their negotiated rates despite high compliance with the price estimator tool requirement. Because patient-oriented price estimator tools make prices visible only for a given patient and insurance plan and not to payers or the public, selective compliance may fail to expose abuses of market power, affect price negotiations, or support broad analysis of price variation to the extent intended by the transparency initiative. Policy makers could consider several strategies to improve compliance, including stiffer penalties, technical assistance, and public reporting of noncompliance.

A limitation of this study is that the low overall compliance must be interpreted in context. We examined websites 65 to 70 days after the rule’s implementation, and the rule took effect during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rule was finalized well before the pandemic, however, and the effective date was set in November 2019. Compliance may increase over time, but the early selective compliance suggests reluctance that may persist.

References

- 1.Verma S. Commentary: you wouldn’t buy a car without knowing the price. So why are health care prices hidden? Chicago Tribune. December 3, 2019. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-opinion-health-care-prices-20191203-mpphzha4ofhwhftwid3od4mxoi-story.html

- 2.Health and Human Services Department . Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020. hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. November 27, 2019. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/27/2019-24931/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2020-hospital-outpatient-pps-policy-changes-and-payment-rates-and#p-1010

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Hospital price transparency frequently asked questions (FAQs). December 23, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/hospital-price-transparency-frequently-asked-questions.pdf

- 4.Sinaiko AD. What is the value of market-wide health care price transparency? JAMA. 2019;322(15):1449-1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glied S.Price transparency—promise and peril. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210316. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Hospital cost report public use file. November 19, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Cost-Report/HospitalCostPUF