Abstract

To accomplish their critical task of removing infected cells and fighting pathogens, leukocytes activate by forming specialized interfaces with other cells. The physics of this key immunological process are poorly understood, but it is important to understand them because leukocytes have been shown to react to their mechanical environment. Using an innovative micropipette rheometer, we show in three different types of leukocytes that, when stimulated by microbeads mimicking target cells, leukocytes become up to 10 times stiffer and more viscous. These mechanical changes start within seconds after contact and evolve rapidly over minutes. Remarkably, leukocyte elastic and viscous properties evolve in parallel, preserving a well-defined ratio that constitutes a mechanical signature specific to each cell type. Our results indicate that simultaneously tracking both elastic and viscous properties during an active cell process provides a new, to our knowledge, way to investigate cell mechanical processes. Our findings also suggest that dynamic immunomechanical measurements can help discriminate between leukocyte subtypes during activation.

Significance

The mammalian immune response is largely based on direct interactions between white blood cells (leukocytes) and pathogens, inert particles, or other host cells. Mechanical properties of leukocytes regulate their migration in the microcirculation to reach their targets, and their interaction with these targets. Yet these mechanical properties and their evolution upon leukocyte activation remain poorly studied. We developed a micropipette-based rheometer to track cell viscous and elastic properties. We show that leukocytes become up to 10 times stiffer and more viscous during their activation. Elastic and viscous properties evolve in parallel, preserving a ratio characteristic of the leukocyte subtype. These mechanical measurements set up a complete picture of the mechanics of leukocyte activation and provide a signature of cell function.

Introduction

The understanding of cell mechanics has progressed with the development of micromanipulation techniques such as micropipette aspiration (1), indentation techniques (2), and others (3). Microfluidics-based approaches such as real-time deformability cytometry now allow high-throughput mechanical measurements (4,5). Yet these techniques make it difficult to track mechanical changes in cells stimulated by soluble molecules (6,7) and even more difficult when cells are stimulated by activating surfaces or partner cells (8).

Tracking these changes can bring a wealth of information on cell function in healthy conditions and diseases. Here, we illustrate this by focusing on white blood cells (leukocytes). These cells, among other functions, fight infected cells or pathogens, remove dead cells, and identify antigens at the surface of other cells and eventually build an immune response against a detected threat. To do so, leukocytes activate by forming with other cells specialized interfaces called immunological synapses. Different leukocytes form different types of synapses, which share several molecular (9) but also mechanical features. One of these mechanical features is force generation, which is now well documented in different types of leukocytes. For instance, we have shown that a T lymphocyte generates forces when forming a synapse (10,11). Others recently showed that B cells generate traction forces during activation (12,13), and Evans et al. quantified decades ago contractile forces generated during phagocytosis (14). The role of these forces is still an open question. Their suggested functions, such as allowing a tight cell-cell contact or probing the mechanical properties of the opposing surface, place these forces at the core of leukocyte activation (15,16). In this study, we focus on another mechanical feature: changes in leukocyte viscoelasticity during their activation. These changes have been shown to exist in T cells, phagocytes, and B cells. We have shown that during activation, T cells stiffen (17). Pioneering observations showed that during phagocytosis, the cortical tension of a phagocyte increases dramatically while this cell engulfs its prey (14,18), and more recent observations confirmed mechanical stiffening of leukocytes during phagocytosis (19). We also recently quantified elastic changes in B cells during activation (20).

As for force generation, the function of the mechanical properties of leukocytes during activation is not yet understood and open to speculation (see Discussion). Yet it is important to quantify and describe them for two reasons. First, we need a complete picture of the mechanics of leukocyte activation to properly incorporate mechanics into currently proposed models of the activation of the different types of leukocytes. Second, beside the fundamental interest of understanding these mechanical changes, they can have very important consequences in the context of disease. Indeed, mechanical properties of leukocyte dictate how easily leukocytes migrate in or out of tissue or flow in small blood vessels (21), so changes of these properties can perturb physiological processes. For instance, circulating neutrophils stimulated by proinflammatory molecules exhibit changes in their mechanical properties (22,23), which contributes to their trapping in pulmonary vasculature in lung diseases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (23,24). Being trapped or slowed down while traveling in a capillary can be due to an increased cell stiffness, but also to an increased cell viscosity. Understanding cell viscous properties is thus also important, although viscous properties are much less explored than elastic ones because of inherent difficulties in quantifying them.

Most measurements of leukocyte mechanics, including the ones mentioned above, were focused on elastic and not viscous properties. However, it was recognized decades ago that leukocytes are viscoelastic and not only elastic (25, 26, 27), so in many situations we miss an important aspect of leukocyte mechanics. Fabry et al. (28) and others have shown that one can expect the viscous properties of leukocytes to be linked to their elastic properties. It was recognized that resting leukocytes such as neutrophils (27,29) and macrophages (30) conserve a ratio of cortical tension/cell viscosity of ∼0.2–0.3 μm/s, even though macrophages can be 10 times more tensed than neutrophils. The ratio of viscous to elastic properties seems to be constrained within a rather narrow range of values, and many studies showed this peculiar aspect of biological matter in various cell types (28,31,32). Here, we asked whether for a given cell type, elastic and viscous properties of leukocytes respected a relationship while they were both evolving over time. To do so, we quantified the evolution of both elastic and viscous properties during the activation of three types of leukocytes. We used a micropipette rheometer to activate leukocytes with standardized activating antibody-covered microbeads (17,33, 34, 35), and we further probed early mechanical changes occurring in leukocyte-target cell contacts by using atomic force microscopy in single-cell force spectroscopy mode (36).

Materials and methods

Micropipette rheometer

The rheometer was build based on the evolution of our profile microindentation setup (37) and micropipette force probe (17,33,38). Micropipettes were prepared as described previously (17,33,37,38) by pulling borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) with a P-97 micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA), cutting them with an MF-200 microforge (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), and bending them at a 45° angle with an MF-900 microforge (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Micropipettes were held by micropipette holders (IM-H1; Narishige) placed at a 45° angle relative to a horizontal plane, so that their tips were in the focal plane of an inverted microscope under brightfield or DIC illumination (T cells: TiE; PLB cells: Ti2; Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 100× oil immersion, 1.3 NA objective (Nikon Instruments), and placed on an air suspension table (Newport, Irvine, CA). The flexible micropipette was linked to a nonmotorized micropositioner (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) placed on top of a single-axis stage controlled with a closed-loop piezo actuator (TPZ001; Thorlabs). The bending stiffness k of the flexible micropipette (∼0.2 nN/μm) was measured against a standard microindenter previously calibrated with a commercial force probe (model 406A; Aurora Scientific, Aurora, Canada). Once the activating microbead was aspirated by the flexible micropipette, the cell held by the stiff micropipette was brought into an adequate position using a motorized micromanipulator (MP-285; Sutter Instruments). Experiments were performed in glass-bottom petri dishes (Fluorodish; World Precision Instruments). Images were acquired using a Flash 4.0 CMOS camera (for T cells) or a SPARK camera (PLB cells), both from Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan. To perform rheological experiments, the setup automatically detects the position of the bead at the tip of the force probe at a rate of 400–500 Hz and imposes the position of the base of the flexible micropipette by controlling the position of the piezo stage. The deflection of the force probe is the difference between the position of the bead and the position of the piezo stage. Thus, the force applied to the cell is the product of this deflection by the bending stiffness k. A retroaction implemented in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) controlling both the camera via the Micro-Manager software (39) and the piezo stage moves the latter in reaction to the measurement of the bead position to keep the desired deflection of the cantilever; a controlled force is applied to the cell at any given time. Experiments were performed at room temperature to avoid thermal drift. Qualitative behavior of T cell and PLB cells is unchanged at 37°C (data not shown). We quantified the fluid drag due to micropipette translation (Supporting materials and methods, Section 1) and the potential effect of fast cell deformation on our rheological measurements (Supporting materials and methods, Section S2). The accuracy when measuring the phase shift depends on the acquisition frequency of both force and cell deformation (xtip), which is 400–500 Hz depending on the size of the region of interest chosen for the acquisition. This leads to a time resolution of 2–2.5 ms. The measured loss tangent had a typical value of η = = tan(φ) ≈ 0.3–0.5, i.e., φ ≈ 0.3–0.5. When expressed in seconds instead of radians, this phase lag represents a delay Δt = , where T = 1 s is the period of the oscillatory force modulation, which leads to Δt = 46–74 ms. This is reasonably long when compared with our time resolution so as to be accurately measured. Note that the uncertainty on the phase lag influenced more K″ than K′ because K″ is proportional to sin(φ), whereas K′ is proportional to cos(φ).

Data analysis

Rheological measurements were analyzed by postprocessing using a custom-made Python code. During force modulation, the sinusoidal xtip signal was fitted every 0.5–1 period interval over a window that was 1.5–2.5 periods long (i.e., every 0.5–1 s with a window of 1.5–2.5 s for a frequency of force modulation f = 1 Hz) using a function corresponding to a linear trend with an added sinusoidal signal (two free parameters for the linear trend, two for the sinusoidal signal when imposing the frequency f = 1 Hz). Best fit was determined using classical squared error minimization algorithm in Python.

T cell experiments

Cells and reagents

Mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood of healthy donors on a Ficoll density gradient. Buffy coats from healthy donors (both male and female donors) were obtained from Etablissement Français du Sang (Paris, France) in accordance with INSERM ethical guidelines. Human total CD4+ isolation kit (130-096-533; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was used for the purification of T cells. Isolated T cells were suspended in FBS:dimethyl sulfoxide (90%:10% vol/vol) and kept frozen in liquid nitrogen. 1–7 days before the experiment, the cells were thawed. Experiments were performed in RPMI 1640 1× with GlutaMax, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all from Life Technologies Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and filtered with 0.22 μm diameter pores (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA).

Beads

Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 for T Cell Expansion and Activation from Gibco were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (ref. 11131D; Carlsbad, CA). These 4.5 μm superparamagnetic polymer beads, coated with an optimized mixture of mouse anti-human monoclonal IgG antibodies against the CD3 and CD28 cell-surface molecules of human T cells, mimic stimulation by an antigen presenting cell (APC). The CD3 antibody is specific for the ε chain of human CD3. The CD28 antibody is specific for the human CD28 costimulatory molecule, which is the receptor for CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2). These beads induce the phosphorylation of several signaling proteins (17,40). Control beads were noncoated 4.5 μm polystyrene beads.

B cell experiments

B cells

Primary B lymphocytes were isolated from spleens of adult C57BL/6J mice (10 to 20 weeks old) and purified by negative selection using the MACS kit (130-090-862) in the total splenocytes. Animal procedures were approved by the CNB-CSIC Bioethics Committee and conform to institutional, national, and EU regulations. Cells were cultured in complete RPMI 1640-GlutaMax-I supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, and 2% sodium pyruvate (denominated hereafter as complete RPMI).

Beads

Silica beads (5 × 106; 5 μm diameter; Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN) were washed in distilled water (5000 rpm, 1 min, RT), incubated with 20 μL 1,2-dioleoyl-PC (DOPC) liposomes containing GPI-linked mouse ICAM-1 (200 molecules/μm2) and biotinylated lipids (1000 molecules/μm2) (10 min, RT), and washed twice with beads buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.5% FCS, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, and 0.5 g/L D-Glucose). Then, lipid-coated beads were incubated with AF647-streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (20 min, RT) followed by biotinylated rat anti-κ light chain antibody (clone 187.1; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (20 min, RT), used as surrogate antigen (su-Ag) to stimulate the B cell receptor. Control beads were coated with ICAM-1-containing lipids only (no su-Ag was added). The number of molecules/μm2 of ICAM-1 and su-Ag/biotin-lipids was estimated by immunofluorometric assay using anti-ICAM-1 or anti-rat-IgG antibodies, respectively; the standard values were obtained from microbeads with different calibrated IgG-binding capacities (Bang Laboratories). The lipid-coated silica beads were finally resuspended in complete RPMI before use. Such a use of lipid-coated silica beads as pseudo-APCs to study immune synapse formation, cell activation, proliferation, and antigen extraction by B cells has been previously set up and reported by us (20,41). They provide the adhesion ligand ICAM-1 for the integrin LFA-1 expressed at the B cell surface and tethered BCR-stimulatory signal (su-Ag) in a fluid phospholipid environment.

PLB cell experiments

Cells and reagents

The human acute myeloid leukemia cell line PLB-985 is a subline of HL-60 cells based on STR fingerprinting (42,43). Gene expression in the two lines is similar but not identical (44). PLB-985 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 1× GlutaMax (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% sterile heat-inactivated FBS and 1% sterile penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were passaged twice a week and differentiated into a neutrophil-like phenotype by adding 1.25% (v/v) of dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to the cell suspension the first day after passage and a second time 3 days after changing the culture media (45). 24 h before experiments, 2000 U/mL IFN-γ (Immuno Tools, Friesoythe, Germany) was added into the cell culture flask, cells were centrifuged for 3 min at 300 × g, and resuspended in 0.22-μm-filtered Hepes medium (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 1.8 mg/mL glucose, and 1% heat-inactivated FBS; filters from Merck Millipore). Differentiated PLB-985 cells stay in suspension and have neutrophil-like properties (Supporting materials and methods, Section S14).

Beads

20 and 8 μm diameter polystyrene microbeads at 106 beads/mL (Sigma-Aldrich) were washed three times by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 3 min and resuspended in Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS; Gibco) filtered with 0.22 μm diameter pores (Merck Millipore). Beads were then incubated overnight at room temperature with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS. Beads were washed again three times by centrifugation at 16,000 × g during 3 min, resuspended in DPBS, and incubated with 1:500 anti-bovine serum albumin rabbit antibody (ref. B1520; Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS for an hour at room temperature. These IgG-coated beads were washed three times by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 3 min with DPBS and resuspended in DPBS at 106 beads/mL before use. Control beads were uncoated polystyrene beads, inducing very rare cases of adhesion with the cell but no phagocytosis. PLB cells tried almost systematically to internalize 20 μm activating beads by performing frustrated phagocytosis and phagocyted 8 μm activating beads.

Atomic force microscope and single-cell force spectroscopy

Cells and reagents

3A9m T cells were obtained from D. Vignali (46) and cultured in RPMI completed with 5% FBS, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM sodium pyruvate in 5% CO2 atmosphere. COS-7 APCs were generated as previously described (47) by stably coexpressing the α and β chains of the mouse MHC class II I-Ak, cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; 5% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes, and geneticin 10 μg/mL). Cells were passaged up to three times a week by treating them with either trypsin/EDTA or PBS 1× (w/o Ca2+/Mg2+), 0.53 mM EDTA at 37°C for up to 5 min.

The anti CD45 antibodies used for this study were produced from the hybridoma collection of CIML, Marseille, France (namely H193.16.3) (48). Briefly, cells were routinely grown in complete culture medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate) before switching to the expansion and production phase. Hybridoma were then cultured in DMEM with decreasing concentrations of low-immunoglobulin FBS down to 0.5%. Cells were then maintained in culture for five additional days, enabling immunoglobulin secretion before supernatant collection and antibody purification according to standard procedures.

The expression of TCR and CD45 molecules on T cells and MHC II molecules on COS-7 APC was assessed once a week by flow cytometry (anti-TCR PE clone H57.597 and anti-CD45 Alexa Fluor 647 clone 30F11 were purchased from BD Pharmingen). The count and the viability, with trypan blue, were assessed automatically twice by using Luna automated cell counter (Biozym Scientific, Vienna, Austria). Mycoplasma test was assessed once a month. Culture media and PBS were purchased from Gibco (Life Technologies). PP2 (Lck inhibitor) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Substrates

Culture-treated, sterile glass-bottom petri dishes (Fluorodish FD35-100; World Precision Instruments) were incubated with 50 μg/mL anti-CD45 antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The surfaces were extensively washed with PBS 1× before a last wash with HBSS 1× 10 mM Hepes. The surfaces were kept wet with HBSS 1× 10 mM Hepes before seeding T cells.

T cell preparation

T cells were counted, centrifuged, and resuspended in HBSS 1× 10 mM Hepes and were kept for 1 h at 37°C 5% CO2 for recovery before seeding. The cells were seeded at room temperature, and after 30 min, a gentle wash was done by using two 1 mL micropipettes to maintain as much as possible a constant volume in the petri dish and hence avoid perturbations by important flows. After 1 h incubation, the petri dish was mounted in a petri dish heater system (JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany) to maintain the temperature of the sample at ∼37°C. 10 min before experiments, 10 μM (final concentration) of Lck kinase inhibitor (PP2 drug) was added and homogenized in the sample. We kept this drug present along all the experiments.

COS-7 APC preparation

The day before the experiment, COS-7-expressing MHCII cells were incubated with the peptide of interest with a final concentration of 10 μM, allowing 100% occupation of MHC II molecules. Before the experiment, the cells were detached from the cell culture plates by removing the cell medium and washing once with PBS 1× and then by a 0.53 mM EDTA treatment for 5 min at 37°C 10% CO2. The cells were resuspended in HBSS 1× 10 mM Hepes and were allowed to recover before to be seeded into the sample. The peptide p46.61 (which is CD4 dependent) was purchased from Genosphere (Paris, France) with a purity >95%.

AFM setup

The setup has been described in great detail elsewhere (49). Measurements were conducted with an AFM (Nanowizard I; JPK Instruments) mounted on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The AFM head is equipped with a 15 μm z-range linearized piezoelectric scanner and an infrared laser. The setup was used in closed-loop, constant height feedback mode (36). MLCT gold-less cantilevers (MLCT-UC or MLCT-Bio DC; Bruker, Billerica, MA) were used in this study. The sensitivity of the optical lever system was calibrated on the glass substrate and the cantilever spring constant by using the thermal noise method. Spring constant were determined using JPK SPM software routines in situ at the start of each experiment. The calibration procedure for each cantilever was repeated three times to rule out possible errors. Spring constants were found to be consistently close to the manufacturer’s nominal values and the calibration was stable over the experiment duration. The inverted microscope was equipped with 10× and 20× NA 0.8 and 40× NA 0.75 lenses and a CoolSnap HQ2 camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Brightfield images were used to select cells and monitor their morphology during force measurements through either Zen software (Zeiss) or Micro-Manager (39).

APC/T cell force measurements

Lever decoration. To make the cantilevers strongly adhesive, we used a modified version of our previous protocols (50). Briefly, cantilevers were activated using a 10 min residual air plasma exposure, then dipped in a solution of 0.25 mg/mL of wheat germ agglutinin or 0.5 mg/mL of concanavalin A in PBS 1× for at least 1 h. They were extensively rinsed by shaking in 0.2-μm-filtered PBS 1× and stored in PBS 1× at 4°C. Before being mounted on the glass block lever holder, they were briefly dipped in MilliQ-H2O to avoid the formation of salt crystals in case of drying and hence alteration of the reflection of the laser signal.

APC capture. In separate experiments, we used side view and micropipette techniques, and we observed that 1) this allows the presented cell to be larger than the lever tip, excluding any unwanted contact of T cell with lectins and 2) the binding is resistant enough to ensure that any rupture event recorded is coming from the cell-cell interface (Supporting materials and methods, Section S3; Fig. S2). After calibration, a lectin-decorated lever is pressed on a given COS7 cell for 20–60 s with a moderate force (typically 1–2 nN), under continuous transmission observation. Then, the lever is retracted far from the surface and the cell is allowed to recover and adhere or spread for at least 5 min before starting the experiments (Fig. S2).

Single-cell force spectroscopy experiment. The surrogate APC is then positioned over a desired T cell. Because the lever is not coated with gold and hence almost transparent, one can finely position the probe over the target. Force curves are then recorded using the following parameters: maximal contact force 1 nN, speeds 2 μm/s, acquisition frequency 2048 Hz, curve length 10 μm, and contact time 60 s. At the end of the retraction, lateral motion of the cells is made by hand by moving the AFM head in the (x, y) plane, relative to the petri dish substrate until no more force is recorded by the lever, signaling that full separation was achieved (Fig. S2). One APC cell was used to obtain one force curve on at least three different T cells, and three APCs at least were used for each condition. No apparent bias was detected in the data when carefully observing the succession of the measures for a given APC, for a given lever, and for a set of T cells.

Data processing and statistics. Force curves were analyzed using JPK Data Processing software on a Linux 64 bit machine. Each curve was evaluated manually, except for calculation and plotting of mean ± standard deviation (SD) for relaxation curves, for which ad hoc Python scripts were used. Data were processed using GraphPad Prism (v7) on a Windows 7 machine. On graphs, data are presented as scatter dot plots with median and interquartile range. A data point corresponds to a force curve obtained for a given coupled T cell-APC except for the small detachment events, for which one data point corresponds to one such event (all events were pooled). Significance was assessed using Mann-Whitney tests in GraphPad Prism v7 with ∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01,∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 below; not significant otherwise.

Results

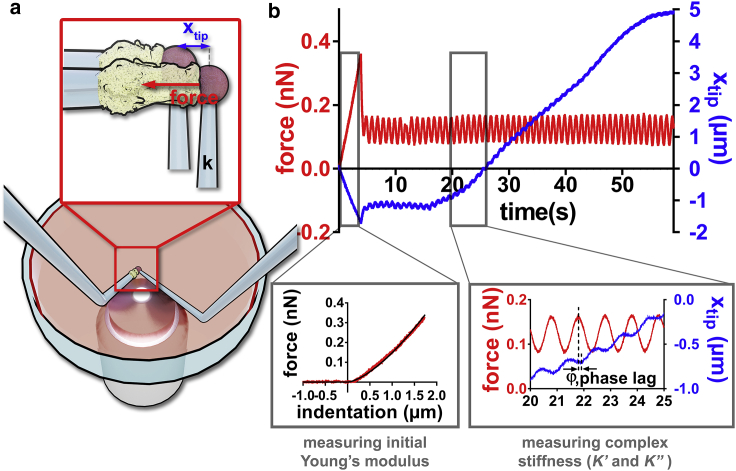

Micropipette rheometer for monitoring rapid morphological and mechanical changes in nonadherent cells

We implemented a real-time feedback loop in our micropipette force probe setup (Fig. 1 a; (17,33)) allowing us to impose a controlled small oscillatory force modulation ΔFcos(ωt) (angular frequency ω = 2πf, frequency f = 1 Hz) superimposed onto a constant force (F). A total force F(t) = (F) + ΔFcos(ωt) is thus applied to the leukocyte during its activation after the contact with an activating microbead coated with cell-specific antibodies. The contact is ensured by pressing the bead against the cell with a force Fcomp (0.12–0.36 nN). This initial compression, from which we extract the cell's effective Young’s modulus EYoung (Fig. 1 b, inset, bottom right; Supporting materials and methods, Section S4; (51,52)), is followed by an imposed force modulation regime, in which we measure oscillations in the position of the tip of the flexible micropipette xtip(t) = <xtip> + Δxtipcos(ωt − φ) of average value xtip, amplitude <xtip> (typically 100 nm, with accuracy within a few nanometers), and phase lag φ. Changes in xtip(t) reflect changes in cell length (Fig. 1 b). Because the cell is shorter when the force is higher, xtip(t) decreases when F(t) increases and corresponds to the lag between a maximum of the force and the following minimum of xtip(t) (Fig. 1 b, inset, bottom right). From xtip(t) and F(t), we deduce the complex cell stiffness K∗ = K′ + iK″, of elastic part K′ = and viscous part K″ = (Supporting materials and methods, Section S5; Video S1). We validated our setup by quantifying K∗ of red blood cells (Video S2). We obtained values of K′ very consistent with values predicted by existing models, and also obtained, as expected, very low values of K″ (Supporting materials and methods, Section S6).

Figure 1.

Rheological measurements during leukocyte activation. (a) Setup. Two micropipettes are plunged in a petri dish. A flexible pipette (right, bending stiffness k ≈ 0.2 nN/μm) holds an activating microbead firmly. A rigid micropipette (left) gently holds a leukocyte (aspiration pressure of 10–100 Pa). The base of the flexible micropipette is displaced to impose a desired force on the cell. (b) Force applied on the cell (in red) and the position xtip of the tip of the flexible micropipette (in blue). The cell is first compressed with a force Fcomp (here 0.36 nN) to measure the initial Young’s modulus of the cell (inset, bottom left). Then an oscillatory force is applied to the cell, leading to an oscillatory xtip signal (inset, bottom right) superimposed to a slower variation of the average value <xtip> because of the growth of a protrusion produced by the leukocyte. To see this figure in color, go online.

(top: T cell, middle: B cell, bottom: PLB cells). All bars represent 5 μm. Time is in minutes:seconds.

The bar represents 5 μm. Time is in minutes:seconds.

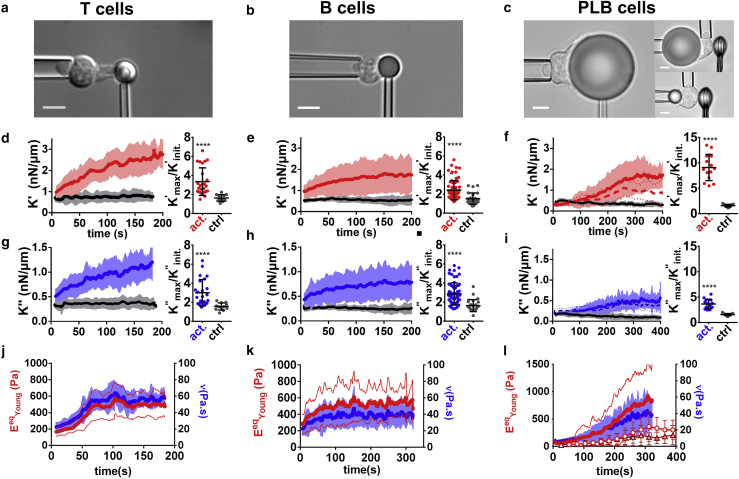

Leukocytes become stiffer and more viscous during activation

We probed three different types of leukocytes during their specific activation and observed qualitatively similar behavior: both K′ and K″ increase and reach a maximum that is three- to eightfold larger than their initial value within few minutes (∼2 min for T and B cells, ∼5 min for neutrophil-like PLB985 cells) after the contact between the leukocyte and the relevant activating microbead (Fig. 2; Video S1). The increase of K′ and K″ is in clear contrast with the constant values obtained using control nonactivating beads (black lines in Fig. 2). Yet it is worth mentioning that the initial value of K′ and K″ is higher for activating beads than for control beads for T and B cells. We explain this by the fact that the initial time point for K′ and K″ is actually already ∼10 s after initial cell-bead contact, leaving some time for early mechanical changes to occur (see later regarding mechanical changes). We evaluated the effect of temperature in the case of T cells by performing experiments at 37°C. T cells behaved qualitatively the same at 37°C but reacted faster and reached higher levels in K′ and K″ (Supporting materials and methods, Section S7).

Figure 2.

Both K′ and K″ increase during leukocyte activation. Each column corresponds to a different cell type. (a–c) Cell morphology. Scale bars, 5 μm. (d-f) Left: K′ for activating (red lines) and nonactivating control beads (gray lines). In (f), the solid red line is for 20 μm beads and the dashed red line for 8 μm beads with indentation in the back (see Fig. 3). Right: maximal/minimal ratio of K′-values for activating and nonactivating control beads. Error bars are SDs. (g–i) Left: K″-values corresponding to K′-values in (d)–(f). In (i), the solid blue line is for 20 μm beads and the dashed blue line for 8 μm beads with indentation in the back (see Fig. 3). Right: maximal/minimal ratio of K″-values for activating and nonactivating control beads. Error bars are SDs. (j–l) Equivalent Young’s modulus (red, left axis) and cell viscosity (blue, right axis). In (l), dots are the Young’s modulus measured in the back of the cell for 20 μm beads, and triangles are for 8 μm beads. In all panels, leukocyte-bead contact time (t = 0) is detected as a force increase; thick lines are mean ± SD over at least three pooled experiments (T cells, 21 cells; B cells, 71 cells; PLB cells, 14 cells). Mann-Whitney test, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. To see this figure in color, go online.

Changes in K′ and K″ correspond to changes in intrinsic leukocyte mechanical properties

Both K′ and K″ depend on cell geometry, so to exclude the possibility that changes in K′ and K″ only reflect geometrical changes, cell-intrinsic mechanical properties such as Young’s modulus and viscosity have to be extracted from K′ and K″. To do so, we first convert K′ and K″ into a storage modulus E′ and a loss modulus E″, respectively. In the case of T cells and B cells, we do so by modeling cell geometry (Supporting materials and methods, Section S8).

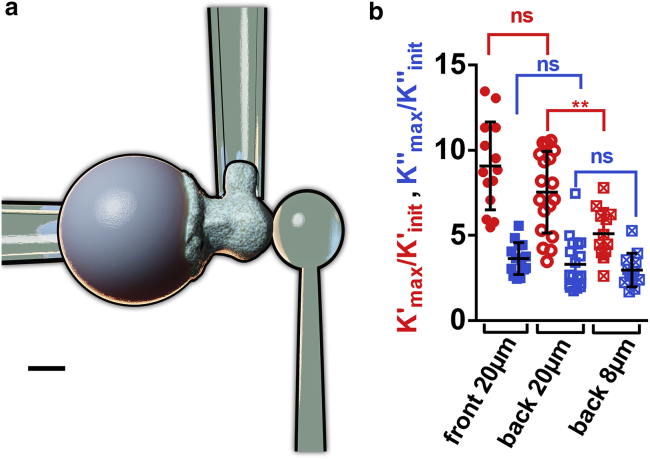

For PLB cells, we use a modified setup in which a nonadherent and nonactivating glass bead indents the cell on its “back” (37) while the cell phagocytoses an activating bead at its “front” (Fig. 3 a; Video S3; (37)). This alternative setup leads to the same increase in K′ and K″ as measured using the original setup with front indentation with an activating bead (Fig. 3 b). Having a sphere-against-sphere geometry, we can use a linearized Hertz model to extract E′ and E″ moduli (Supporting materials and methods, Section S8). Lastly, we performed cyclic indentation experiments to measure directly the Young’s modulus over time (with a limited time resolution of ∼30 s; dotted curves in Fig. 2 l); indentation occurs only for a short time at the beginning of each cycle, after which the indenter retracts from the cell, marking the end of a cycle, immediately followed by a new cycle (Video S4). In the case of PLB cells, we tested the influence of bead size by performing indentation in the “back” of cells phagocytosing either 20 or 8 μm beads. For both bead sizes, the cells’ Young’s modulus increased significantly during phagocytosis when comparing early (t = 52 s) versus late (t = 286 s) times (Fig. 2 l, EYoung (t = 286 s) > EYoung (t = 52 s), at least 14 cells from at least three independent experiments for each condition, p < 0.0001 for 20 and 8 μm beads, Mann-Whitney test).

Figure 3.

Indenting the “back” of a phagocyte during activation. (a) Modified setup. A stiff pipette holds the activating microbead (left), an auxiliary (stiff) pipette holds the cell by its “side” (top), and a flexible pipette whose tip consists of a nonadherent glass bead indents the cell on its “back” (right). Scale bar, 5 μm. (b) Maximal/minimal ratios for K′ and K″ obtained with both versions of the setup during PLB cell activation (ns: nonsignificant, two-tailed unpaired t-test). Using back indentation, in addition to the 20 μm beads used with the nonmodified setup, 8 μm beads were tested. Error bars are SDs. To see this figure in color, go online.

The bar represents 10 μm. Time is in minutes:seconds.

The bar represents 10 μm. Time is in minutes:seconds.

To allow a simple interpretation of E′ and E″, which were obtained in a regime of oscillatory forces, we convert them into an effective Young’s modulus and an effective viscosity ν, respectively. To calculate , we compare the Young’s modulus measured by initial compression and E′ measured right after, when force modulation begins (Supporting materials and methods, Section S9; Fig. S6). For PLB cells, we used cyclic back indentation again as described above to measure both Young’s modulus and E′ not only at initial time but during the whole activation. This showed that E′ and EYoung are proportional, with a phenomenological coefficient C such that E′ = CEYoung. C is measured to be constant over time for PLB cells, and so for T and B cells, we assume that C is also constant over time (Supporting materials and methods, Section S9).

Using this approach, we measured the effective Young’s modulus of the three cell types over time (Fig. 2, j–l). To calculate the effective cell viscosity, we consider a simple model consistent with a Newtonian liquid and cortical tension model of a cell (2), in which a Newtonian viscosity is introduced as ν = E″/ω. The resulting Young’s modulus and viscosity increase until reaching a maximal value that is two- to threefold higher than the baseline value for T and B cells, and ∼11-fold higher for PLB cells (Fig. 2, j–l).

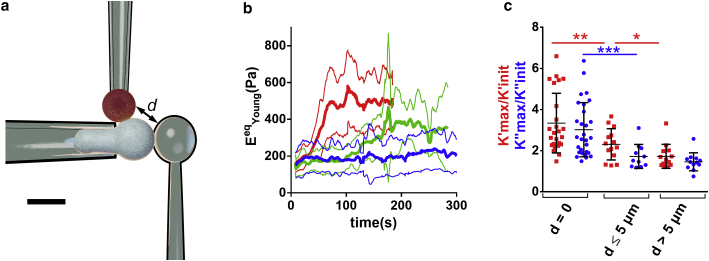

Mechanical changes are localized close to the cell-bead interface

We asked whether mechanical changes were localized close to the activation area in the leukocyte. In the case of T cells, we used a modified setup similar to the one allowing to indent PLB cells on their back (Fig. 3 a). In that case, an auxiliary pipette brought the activating microbead in contact with the T cell on its “side”: at the equatorial plane (distance between the activating and indenting beads smaller than 5 μm) or close to the tip of the holding pipette, at the farthest possible location from the activating bead (distance between the activating and indenting beads larger than 5 μm, Fig. 4; Video S5). This allowed us to quantify mechanical changes during activation depending on the distance to the cell-bead contact area. We computed an equivalent Young’s modulus EeqYoung as described in Supporting materials and methods, Section S9, which led to a good agreement with EYoung measured at the initial time. T cells exhibited a different behavior depending on the location of the activating microbead; the closer the indenter was to the activating bead, the larger the maximal value of EeqYoung measured during activation. Cell stiffening thus occurs with a different amplitude depending on the location on the cell relative to the contact zone with an activating surface.

Figure 4.

(a) Modified setup in which an auxiliary (stiff) pipette holds the activating microbead (top, red) to bring it in contact with the T cell at a chosen distance from a microindenter (right), which indents the cell on its “side” while the T cell gets activated. Scale bar, 5 μm. (b) Equivalent Young’s modulus for three different ranges of distance d between the activating bead and the microindenter (red: d = 0; green: 0 < d ≤ 5 μm; blue: d > 5 μm). Thick lines are means, thin lines are SDs. (c) K′max/K′init (red) and K″max/K″init (blue) ratios for the same ranges of distance d as in (b). Error bars are SDs. To see this figure in color, go online.

The bar represents 5 μm. Time is in minutes:seconds.

Mechanical changes in T cells start within seconds

In T cells, mechanical changes precede morphological ones; K′ increases slowly within seconds after cell-bead contact, before cell morphology starts changing (i.e., before the T cell produces a large protrusion (17); Video S1). The onset of this growth is followed by a short period during which K′ stays relatively constant. This phase ends by a faster increase of K′ during protrusion growth (Supporting materials and methods, Section S10; Fig. S7). The start of the faster increase in K′ starts when the tail of the cell in the holding pipette starts retracting (a sign that K′ and cell tension are two equivalent ways to describe cell stiffness; Supporting materials and methods, Section S11). Of note, T cells have large membrane surface stores (38), so it is unlikely that the acceleration in K′ increase could be explained by reaching the limits of membrane stores (Supporting materials and methods, Section S12).

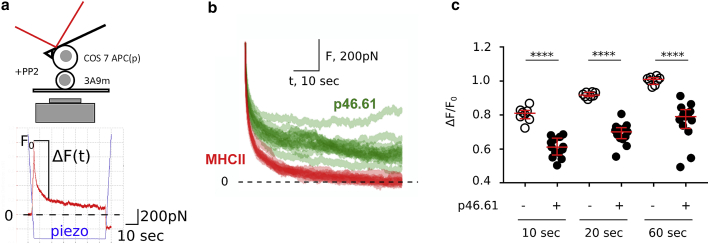

AFM measurements of early mechanical changes after T cell-APC contact

To confirm with an independent technique that T cell mechanics may be modulated within seconds when it encounters an APC before any large morphological change occurs, we used AFM and performed single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) experiments (Fig. 5 a; Supporting materials and methods, Section S3; (36)). As a model APC, we used COS-7 cells expressing MHCII molecules that can be loaded with peptides of desired affinity as previously shown (47,48). We used murine 3A9m T cells and immobilized them on a coverslip by adhering them using anti-CD45 antibodies (53). To measure rapid mechanical changes using this technique, we prevented potential large active cell deformations by using the pan-Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (Materials and methods). Although PP2 inhibits TCR-mediated Lck- or Fyn-dependent intracellular phosphorylation events and downstream signaling cascades (54), it does not inhibit all molecular events such as migration arrest, kinapse, or microcluster formation upon T cell activation (55, 56, 57). The washout experiment showed that PP2 in fact enables to pause signalization without abrogating the antigen dependence of early T cell activation (58,59).

Figure 5.

Cell-cell presentation induces early changes in force relaxation. (a) AFM SCFS setup (top) and example of individual force (in red) versus time curve (bottom). The piezo signal (in blue) reports the position of the base of the cantilever. (b) Relaxation part of force curves, for peptide (p46.61) versus no-peptide (MHCII) cases. One curve corresponds to one cycle, i.e., 1 APC-T cell couple. See Document S1. Supporting materials and methods and Figs. S1–S10, Video S1. Activation of three types of leukocytes studied with the micropipette rheometer, Video S2. Validation of the micropipette rheometer by performing microindentation measurements on a red blood cell, Video S3. Modified setup to indent the “back” of a PLB cell while the cell phagocytoses an activating bead on its “front”, Video S4. Cyclic indentation experiments to directly measure the Young’s modulus over time of a PLB cell phagocytozing an activating bead, Video S5. Modified setup using an auxiliary pipette to bring an activating microbead in contact with a T cell on its “side”h for plot of mean ± SD curves. (c) Quantification of the relaxation for three different time points for MHCII (−) and MHCII/p46.61 (+); ΔF/F0 is the ratio of the drop in force ΔF and the force level F0 imposed at initial time 0 (see a). This ratio is shown at three different times after cell-cell contact (10, 20, and 60 s) and shows a consistently lower ratio (hence a slower relaxation) in presence of the peptide (∗∗∗∗p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney). Bars are median and interquartile ranges. To see this figure in color, go online.

The SCFS experiments provide for each cell doublet the force-tip sample separation curve, which is the AFM equivalent of the force-indentation curve shown in Fig. 1 b (inset, bottom left), with three parts: 1) pushing the cells together, 2) maintaining the contact, and 3) detaching the cells by pulling them apart. The contact mechanics at initial time was quantified by measuring the slope of the force-tip sample separation curve (called contact slope herein), which reflects the stiffness of the cell doublet. This contact slope was not modified by the presence or absence on the APC of the hen egg lysozyme (peptide p46.61)-derived peptide recognized by the murine 3A9m T cells (Document S1. Supporting materials and methods and Figs. S1–S10, Video S1. Activation of three types of leukocytes studied with the micropipette rheometer, Video S2. Validation of the micropipette rheometer by performing microindentation measurements on a red blood cell, Video S3. Modified setup to indent the “back” of a PLB cell while the cell phagocytoses an activating bead on its “front”, Video S4. Cyclic indentation experiments to directly measure the Young’s modulus over time of a PLB cell phagocytozing an activating bead, Video S5. Modified setup using an auxiliary pipette to bring an activating microbead in contact with a T cell on its “side” d). However, in the separation part of the force curves, the presence of the peptide induced an increase in the force needed to fully detach the two cells in parallel with an increase of the number of discrete separation events, indicating that the interaction was indeed peptide specific (Fig. S2, e and f).

The measurement of the contact slope corresponds to the very first instant of cell-cell contact (Fig. 5 a, bottom). To measure cell mechanical changes after this contact, we quantified the force relaxation when the AFM lever motion was stopped and piezo position was kept constant after reaching a contact force of 1 nN (Fig. 5, b and c). We observed a striking difference in this force relaxation depending on the presence versus absence of a saturating concentration of the antigenic peptide (Fig. 5 b); the force relaxation was much slower in presence of the antigenic peptide, as quantified by the lower value of the ratio ΔF/F0 at different times after the start of the relaxation (Fig. 5 c). This measurement reflects global viscoelastic properties of the cell-cell doublet but does not disentangle elastic and viscous properties. Furthermore, having the two cells pressed against each other in series does not allow simply excluding a contribution of a mechanical change in the APC. However, mechanical properties of APC COS-7 cells were not modified by the presence of the peptide (Fig. S3). As a consequence, we expect that the major contribution to the difference in force relaxation is indeed due to the T cell. Our SCFS experiments are thus consistent with our micropipette force probe experiments and show that specific recognition during T cell-APC contact may induce mechanical changes within a few seconds and without any TCR signaling.

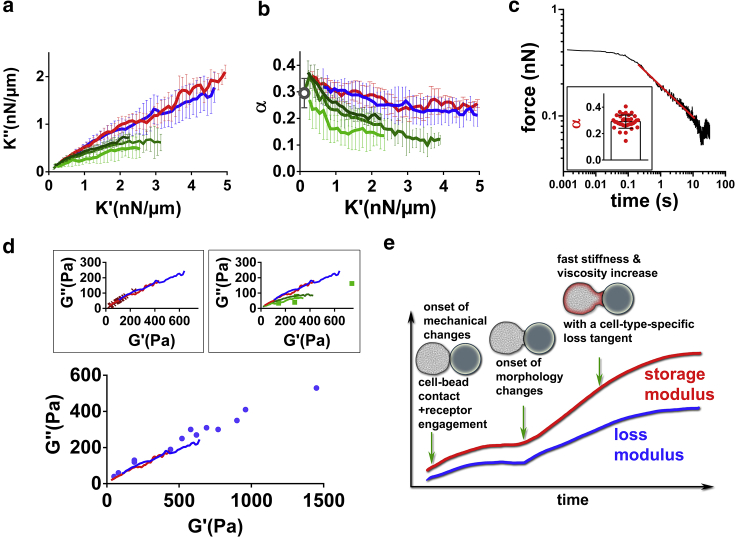

Relationship between elastic and viscous properties during leukocyte activation

We then asked whether variations in elastic and viscous properties were related to each other. Prior works show that in several cell types, the loss modulus E″ and storage modulus E′ of a cell are related to each other. In fact, their ratio η = , the loss tangent, lies within a narrow range of 0.1–0.3 (6,28,31,60, 61, 62). For a material such as a purely viscous liquid, the storage modulus vanishes so that η is arbitrarily large, whereas for a purely elastic material, the loss modulus vanishes and so does η. A finite and constant value of η for a cell implies that the stiffer the cell, the more viscous it is. This narrow range of loss tangent is consistent with the conserved ratio of cortical tension to cell viscosity in leukocytes (see Introduction). In biological matter, similar to soft glassy materials (63,64), stress relaxation over time often follows a power-law (with an exponent that we shall call α) (31,32,60,65,66). The loss tangent η is frequency dependent and is expected to be approximately equal to tan at low frequencies (Supporting materials and methods, Section S13). Therefore, by measuring the power-law exponent α independently, we should recover the value of η = (which should also be equal to because the contribution from geometry is eliminated in this ratio (7)). To test this prediction, we performed stress relaxation experiment on resting PLB cells (Fig. 6 c) and obtained values for α that were very consistent with the predicted value of (which is equivalent to comparing and ; gray circle in Fig. 6 b). We then compared K″ vs. K′ curves obtained during activation of T cells, B cells, and PLB cells (Fig. 6 a). In Fig. 6 b, we plot the corresponding value of α = ; these curves are remarkably consistent for T and B cells, and for PLB cells, K″-K′ curves obtained by indentation in the front and in the back of the cell are very similar and differ from the T and B cell common curve. Interestingly, Bufi et al. (67) measured storage and loss moduli of various leukocytes at resting state or after priming by different inflammatory signals. Their data lead to a loss tangent η consistent with our measurements (Fig. 6 d), but their measurements were made at a single time point. Maksym et al. (6) tracked over time both the loss and storage moduli of human airway smooth muscle cells contracting because of the administration of histamine (Fig. 6 d, inset, top left). Their data are again very consistent with our measurements. Roca-Cusachs et al. (2) used AFM on neutrophils and found a loss tangent very consistent with our measurements on PLB cells obtained with 20 and 8 μm beads (Fig. 6 d, inset, top right).

Figure 6.

Relationship between elastic and viscous cell properties (a) K″ vs. K′ during activation of T cells (red), B cells (blue), and PLB cells (front indentation: green (20 μm beads), back indentation: light green (20 μm beads) and dark green (8 μm beads)). Error bar are SDs. (b) α = , corresponding to the same data as in (a). The gray circle is the value of the power-law exponent in force relaxation experiments on resting PLB cells. (c) Example of force relaxation curve of a PLB cell. In the log-log plot, a power-law relaxation is identified by the straight line (red), whose slope is the exponent α. Inset: individual α-values (one dot per cell). (d) Loss modulus G″ vs. storage modulus G′ obtained by Bufi et al. (67) (bottom, blue dots), Maksym et al. (6) (inset, top left, red crosses), and Roca-Cusachs et al. (2) (inset, top right, green dots). Our data from (a) (red and blue solid lines) are consistent with the abovementioned published data. (e) Proposed model of mechanical changes during leukocyte activation. To see this figure in color, go online.

Based on our results, we propose a simple model of leukocyte mechanical changes during activation (Fig. 6 e): mechanical changes begin seconds after receptor engagement at the leukocyte surface. Cell morphological changes start a few tens of seconds later, concomitant with stiffening and increase in viscosity. Viscous and elastic properties of the leukocyte evolve following a characteristic relationship defined by the loss tangent.

Discussion

We showed that during activation, various types of leukocytes see their stiffness and viscosity increase significantly within few minutes. The initiation of mechanical changes upon contact with an activating surface starts within seconds and these changes precede morphological changes. By using the same technique—avoiding potential differences due to different techniques (3)—we show for the first time, to our knowledge, with ∼1 s time resolution how both viscous and elastic properties evolve during immune cell activation. We further show that elastic and viscous properties follow a relationship that is cell-type dependent; T and B cells keep the same ratio between viscous and elastic properties, whereas neutrophils follow a different ratio, independently of the size of their target.

Most published measurements of cell viscosity were performed on leukocytes in a resting state. Some micropipette aspiration studies led to leukocyte viscosity in the range of 100–200 Pa.s (68, 69, 70, 71) and are consistent with values obtained in fibroblasts (72). These values are higher than the viscosities of ∼5–20 Pa ⋅ s that we measured in resting leukocytes. This discrepancy might be explained by model dependence and by differences in the shear rate applied to cells. Our measurements are much closer to results by other groups; Sung et al. (73) obtained a cytotoxic T cell viscosity of ∼30 Pa ⋅ s, Schmid-Schönbein et al. (25) measured a leukocyte viscosity of ∼13 Pa ⋅ s, and Hochmuth et al. (29) extrapolated a value for neutrophil viscosity of ∼60 Pa ⋅ s. Interestingly, Lipowsky et al. (74) did not restrict to baseline viscosity and studied neutrophils stimulated by the chemoattractant FMLP. The authors reported a neutrophil viscosity increasing from ∼5 Pa ⋅ s at resting state to ∼70 Pa ⋅ s upon stimulation.

Mechanical changes might not have a function per se but might be concomitant to force generation by cells. Indeed, cell contractility and cell stiffness are correlated in muscle cells (75, 76, 77, 78, 79), and single cells mirror mechanical and energetic features of muscle contraction; single myoblasts follow a single-cell equivalent of a Hill relationship between force generation and rate of contraction (80,81). Furthermore, it also appears that single muscle cells become stiffer when they contract; Shroff et al. (79) observed a roughly twofold increase in the stiffness of a cardiomyocyte during its contraction. Although leukocytes have a different organization of their actomyosin cytoskeleton, it is tempting to speculate that all leukocytes share generic cytoskeletal-based properties requiring that cells stiffen to generate force. This could explain the apparent contradiction that in leukocytes, the stiffening that we have quantified occurs in situations requiring an efficient spreading. Indeed, phagocytes need to increase their surface by spreading on their prey to engulf it, whereas T and B cells need to spread widely on the cell they encounter to quickly scan a surface that is as large as possible on the cell they interact with (18,82). Alternatively, forming a stiff synapse might allow its stabilization (83,84).

Although the molecular details leading to changes in viscoelastic properties are yet to be understood, cell-scale physical considerations allowed Evans et al. (71,85) to conclude that viscous properties of cells are conferred by bulk components of the cell, as opposed to surface viscosity due to the actin cortex. As a result, we expect that the large increase in the viscous properties of leukocytes that we observed are largely due to intracellular reorganization, not only cortical reorganization. Interestingly, Tsopoulidis et al. recently showed that T cell receptor engagement triggers the formation of a nuclear actin network in T cells (86), which could contribute to these bulk mechanical changes. Fritzsche et al. observed submembrane actin pattern reorganization that influenced the membrane architecture of HeLa cells, but not their mechanical properties (87). These observations may lift an apparent contradiction in T cells, in which the formation of an immunological synapse requires actin to depolymerize at the center of the synapse, including in cytotoxic T cells where actin gets actually depleted across the synapse within 1 min (88). Other contributors must then explain the stiffening that we observe, and in addition to the nuclear actin network (86), another possible contributor may be a secondary actin network. Indeed, Fritzsche et al. (84) found in T cells that besides the dense cortical network forming a rosette-shaped structure in the basal lamellipodium and devoid of actin at its center up to 3 min after initial contact, another actin network assembles 150–300 nm above the cell-substrate contact.

We expect inner reorganizations causing mechanical changes to impact inner cell dynamics, such as organelle trafficking. This includes mitochondrial relocation that is known to happen in several types of leukocytes upon activation (89,90). Regarding the cell surface, although we dismissed surface effects as key contributors to cell viscosity, surface receptors are transmembraneous, so the formation of diffusional barriers with slowed diffusion at the cell surface as observed during leukocyte activation could be one manifestation of the increase in cell viscosity (91,92). As an alternative to the above considerations that mechanical changes might not have a specific function, these changes in viscosity might help confining molecules of interest in the vicinity of the synapse. By sequestering these molecules because of higher stiffness and viscosity (implicating an increased energetical cost to move away from this zone), early mechanical changes might help integrate at the cellular scale the information input incoming from the single-receptor scale at the synapse. Considering this efficient processing from nano- to microscale is also worth integrating in mechanistic description of early immunological signaling, including models considering a frictional coupling of the TCR to the cytoskeleton (93,94).

Our study highlights that variations of both elastic and viscous properties are relevant to understand immune cell mechanics during activation, as well as their relationship in the form of the loss tangent η, and how the latter evolves over time. All the leukocytes that we tested show very large changes in both elastic and viscous properties, but monitoring the time evolution of the loss tangent exhibits a mechanical fingerprint specific to cell types. It is tempting to speculate that the evolution of the loss tangent during activation can become a valuable tool to discriminate between healthy and pathological leukocytes, as already suggested by considering static values of η (95).

Finally, our observations suggest a possible generalization to cells other than leukocytes. In line with what was observed by Thoumine et al. (96) in fibroblasts or Abidine et al. in epithelial cancer cells (97), we propose that getting stiffer and more viscous while spreading is a common behavior across cell types. The time evolution of the loss tangent during cell spreading remains to be explored.

Author contributions

P.-H.P., Y.H., and J.H. designed experiments. A.Z., S.V.M.-C., A.S., F.M., Y.H., P.-H.P., and J.H. performed experiments. A.Z., A.S., Y.H., P.-H.P., and J.H. analyzed the data. A.B., S.D., E.H., S.D.-C., H.-T.H., A.I.B., Y.R.C., Y.H., C.H., and O.N. contributed material. P.-H.P. and J.H. wrote the manuscript with helpful critical reading by the other authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D. Gonzalez-Rodriguez (LCP-A2MC, Univ. De Lorraine), R. Roncagalli (CIML), P. Recouvreux (IBDML), and L. Limozin and F. Rico (LAI) for discussion and support. The authors also thank Leila Bouchab, Jérémy Joly, Gwladys Texier; L. B. was a recipient of a doctoral grant from Region Ile de France (DIM Malinf, France).

This work has benefited from the financial support of the Labex LaSIPS (ANR-10-LABX-0040-LaSIPS) managed by the French National Research Agency (France) under the “Investissements d’avenir” program (no. ANR-11-IDEX-0003-02), from a CNRS PEPS (France) grant, from Ecole Polytechnique (Palaiseau,France), from an endowment in cardiovascular bioengineering from the AXA Research Fund, and from the platform SpICy at Institut de Chimie Physique (France). This work was supported by funding from 1) Prise de Risques CNRS and ANR JCJC « DissecTion » (to P.-H.P.); 2) the Labex IN-FORM (ANR-11-LABX-0054) and A∗MIDEX project (ANR-11-IDEX-0001-02), sponsored by the Investissements d’Avenir project funded by the French Government, managed by the French National Research Agency (to LAI and CIML and as PhD grant to A.S.); and 3) the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 713750, with the financial support of the Regional Council of Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (France) and with of the A∗MIDEX (no ANR- 11-IDEX-0001-02), funded by the Investissements d’Avenir project funded by the French Government, managed by the French National Research Agency (as PhD grant to F.M.). Part of this work was also supported by institutional grants from Inserm (France), CNRS (France), and Aix-Marseille University (France) to the LAI and CIML. S.D. and C.H. have benefited from funding by French National Research Agency (France): ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL∗ and ANR-11-LABX-0043. Material or technical help: R. Balland (Sensome) for RBCs; M. Pélicot-Biarnes (LAI); L. Borge (PCC cell culture facility); S. Mailfert, M. Fallet, and PICSL imaging facility of the CIML (ImagImm), member of the national infrastructure France-BioImaging supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-INBS-04); and A. Formisano (He and Marguet lab). Companies: F. Eghiaian, T. Plake, and JPK Instruments (Berlin, Germany), now part of Bruker, are thanked for continuous support and generous help, and Zeiss France for support. S.V.M.-C. and Y.R.C. have benefited from the financial support of an FPI contract (BES-2014-068006) and the grant BFU2013-48828-P from the Spanish Ministry of Economy.

Editor: Paul Janmey.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.02.042.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Hochmuth R.M. Micropipette aspiration of living cells. J. Biomech. 2000;33:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roca-Cusachs P., Almendros I., Navajas D. Rheology of passive and adhesion-activated neutrophils probed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3508–3518. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu P.-H., Aroush D.R.-B., Wirtz D. A comparison of methods to assess cell mechanical properties. Nat. Methods. 2018;15:491–498. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toepfner N., Herold C., Guck J. Detection of human disease conditions by single-cell morpho-rheological phenotyping of blood. eLife. 2018;7:e29213. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillou L., Dahl J.B., Kumar S. Measuring cell viscoelastic properties using a microfluidic extensional flow device. Biophys. J. 2016;111:2039–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maksym G.N., Fabry B., Fredberg J.J. Mechanical properties of cultured human airway smooth muscle cells from 0.05 to 0.4 Hz. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;89:1619–1632. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith B.A., Tolloczko B., Grütter P. Probing the viscoelastic behavior of cultured airway smooth muscle cells with atomic force microscopy: stiffening induced by contractile agonist. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2994–3007. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dura B., Dougan S.K., Voldman J. Profiling lymphocyte interactions at the single-cell level by microfluidic cell pairing. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5940. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niedergang F., Di Bartolo V., Alcover A. Comparative anatomy of phagocytic and immunological synapses. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:18. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hivroz C., Saitakis M. Biophysical aspects of T lymphocyte activation at the immune synapse. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:46. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huse M. Mechanical forces in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:679–690. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., Lin F., Liu W. Profiling the origin, dynamics, and function of traction force in B cell activation. Sci. Signal. 2018;11:eaai9192. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aai9192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumari A., Pineau J., Pierobon P. Actomyosin-driven force patterning controls endocytosis at the immune synapse. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2870. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans E., Leung A., Zhelev D. Synchrony of cell spreading and contraction force as phagocytes engulf large pathogens. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:1295–1300. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.6.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumari S., Mak M., Irvine D.J. Cytoskeletal tension actively sustains the migratory T-cell synaptic contact. EMBO J. 2020;39:e102783. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019102783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masters T.A., Sheetz M.P., Gauthier N.C. F-actin waves, actin cortex disassembly and focal exocytosis driven by actin-phosphoinositide positive feedback. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2016;73:180–196. doi: 10.1002/cm.21287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawicka A., Babataheri A., Husson J. Micropipette force probe to quantify single-cell force generation: application to T-cell activation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:3229–3239. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herant M., Heinrich V., Dembo M. Mechanics of neutrophil phagocytosis: behavior of the cortical tension. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1789–1797. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irmscher M., de Jong A.M., Prins M.W.J. A method for time-resolved measurements of the mechanics of phagocytic cups. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2013;10:20121048. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merino-Cortés S.V., Gardeta S.R., Carrasco Y.R. Diacylglycerol kinase ζ promotes actin cytoskeleton remodeling and mechanical forces at the B cell immune synapse. Sci. Signal. 2020;13:eaaw8214. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaw8214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekpenyong A.E., Toepfner N., Chilvers E.R. Mechanical deformation induces depolarization of neutrophils. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1602536. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Worthen G.S., Schwab B., III, Downey G.P. Mechanics of stimulated neutrophils: cell stiffening induces retention in capillaries. Science. 1989;245:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.2749255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bashant K.R., Vassallo A., Toepfner N. Real-time deformability cytometry reveals sequential contraction and expansion during neutrophil priming. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019;105:1143–1153. doi: 10.1002/JLB.MA0718-295RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preira P., Forel J.-M., Theodoly O. The leukocyte-stiffening property of plasma in early acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) revealed by a microfluidic single-cell study: the role of cytokines and protection with antibodies. Crit. Care. 2016;20:8. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1157-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid-Schönbein G.W., Sung K.L., Chien S. Passive mechanical properties of human leukocytes. Biophys. J. 1981;36:243–256. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84726-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans E.A. Structural model for passive granulocyte behaviour based on mechanical deformation and recovery after deformation tests. Kroc Found. Ser. 1984;16:53–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tran-Son-Tay R., Needham D., Hochmuth R.M. Time-dependent recovery of passive neutrophils after large deformation. Biophys. J. 1991;60:856–866. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82119-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabry B., Maksym G.N., Fredberg J.J. Scaling the microrheology of living cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:148102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochmuth R.M., Ting-Beall H.P., Tran-Son-Tay R. Viscosity of passive human neutrophils undergoing small deformations. Biophys. J. 1993;64:1596–1601. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81530-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam J., Herant M., Heinrich V. Baseline mechanical characterization of J774 macrophages. Biophys. J. 2009;96:248–254. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alcaraz J., Buscemi L., Navajas D. Microrheology of human lung epithelial cells measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2071–2079. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahaffy R.E., Park S., Shih C.K. Quantitative analysis of the viscoelastic properties of thin regions of fibroblasts using atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1777–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basu R., Whitlock B.M., Huse M. Cytotoxic T cells use mechanical force to potentiate target cell killing. Cell. 2016;165:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Husson J., Chemin K., Henry N. Force generation upon T cell receptor engagement. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zucchetti A.E., Paillon N., Husson J. Influence of external forces on actin-dependent T cell protrusions during immune synapse formation. Biol. Cell. 2021 doi: 10.1111/boc.202000133. Published online January 20, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puech P.H., Poole K., Muller D.J. A new technical approach to quantify cell-cell adhesion forces by AFM. Ultramicroscopy. 2006;106:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guillou L., Babataheri A., Husson J. Dynamic monitoring of cell mechanical properties using profile microindentation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21529. doi: 10.1038/srep21529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillou L., Babataheri A., Husson J. T-lymphocyte passive deformation is controlled by unfolding of membrane surface reservoirs. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:3574–3582. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-06-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edelstein A.D., Tsuchida M.A., Stuurman N. Advanced methods of microscope control using μManager software. J. Biol. Methods. 2014;1:e10. doi: 10.14440/jbm.2014.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larghi P., Williamson D.J., Hivroz C. VAMP7 controls T cell activation by regulating the recruitment and phosphorylation of vesicular Lat at TCR-activation sites. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:723–731. doi: 10.1038/ni.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roman-Garcia S., Merino-Cortes S.V., Carrasco Y.R. Distinct roles for Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase in B cell immune synapse formation. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2027. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drexler H.G., Dirks W.G., MacLeod R.A.F. False leukemia-lymphoma cell lines: an update on over 500 cell lines. Leukemia. 2003;17:416–426. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romano P., Manniello A., Parodi B. Cell Line Data Base: structure and recent improvements towards molecular authentication of human cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D925–D932. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rincón E., Rocha-Gregg B.L., Collins S.R. A map of gene expression in neutrophil-like cell lines. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:573. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4957-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedruzzi E., Fay M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M.A. Differentiation of PLB-985 myeloid cells into mature neutrophils, shown by degranulation of terminally differentiated compartments in response to N-formyl peptide and priming of superoxide anion production by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Br. J. Haematol. 2002;117:719–726. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vignali D.A., Strominger J.L. Amino acid residues that flank core peptide epitopes and the extracellular domains of CD4 modulate differential signaling through the T cell receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1945–1956. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salles A., Billaudeau C., Hamon Y. Barcoding T cell calcium response diversity with methods for automated and accurate analysis of cell signals (MAAACS) PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hueber A.O., Pierres M., He H.T. Sulfated glycans directly interact with mouse Thy-1 and negatively regulate Thy-1-mediated adhesion of thymocytes to thymic epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1992;148:3692–3699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cazaux S., Sadoun A., Puech P.H. Synchronizing atomic force microscopy force mode and fluorescence microscopy in real time for immune cell stimulation and activation studies. Ultramicroscopy. 2016;160:168–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franz C.M., Taubenberger A., Muller D.J. Studying integrin-mediated cell adhesion at the single-molecule level using AFM force spectroscopy. Sci. STKE. 2007;2007:pl5. doi: 10.1126/stke.4062007pl5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson K.L. Contact mechanics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;37:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenbluth M.J., Lam W.A., Fletcher D.A. Force microscopy of nonadherent cells: a comparison of leukemia cell deformability. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2994–3003. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadoun A., Biarnes-Pelicot M., Puech P.-H. Controlling T cells shape, mechanics and activation by micropatterning. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.09.15.295964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanke J.H., Gardner J.P., Connelly P.A. Discovery of a novel, potent, and Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Study of Lck- and FynT-dependent T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moreau H.D., Lemaître F., Bousso P. Signal strength regulates antigen-mediated T-cell deceleration by distinct mechanisms to promote local exploration or arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:12151–12156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506654112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campi G., Varma R., Dustin M.L. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1031–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yokosuka T., Sakata-Sogawa K., Saito T. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Faroudi M., Zaru R., Valitutti S. Cutting edge: T lymphocyte activation by repeated immunological synapse formation and intermittent signaling. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1128–1132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osborne D.G., Wetzel S.A. Trogocytosis results in sustained intracellular signaling in CD4(+) T cells. J. Immunol. 2012;189:4728–4739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kollmannsberger P., Fabry B. Linear and nonlinear rheology of living cells. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2011;41:75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balland M., Desprat N., Gallet F. Power laws in microrheology experiments on living cells: comparative analysis and modeling. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2006;74:021911. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.021911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bursac P., Lenormand G., Fredberg J.J. Cytoskeletal remodelling and slow dynamics in the living cell. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nmat1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sollich P. Rheological constitutive equation for a model of soft glassy materials. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys., Plasmas, Fluids, Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 1998;58:738–759. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fabry B., Fredberg J.J. Remodeling of the airway smooth muscle cell: are we built of glass? Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2003;137:109–124. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fabry B., Maksym G.N., Fredberg J.J. Time scale and other invariants of integrative mechanical behavior in living cells. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68:041914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.041914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takahashi R., Okajima T. Mapping power-law rheology of living cells using multi-frequency force modulation atomic force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;107:173702. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bufi N., Saitakis M., Asnacios A. Human primary immune cells exhibit distinct mechanical properties that are modified by inflammation. Biophys. J. 2015;108:2181–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsai M.A., Waugh R.E., Keng P.C. Passive mechanical behavior of human neutrophils: effects of colchicine and paclitaxel. Biophys. J. 1998;74:3282–3291. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)78035-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsai M.A., Frank R.S., Waugh R.E. Passive mechanical behavior of human neutrophils: effect of cytochalasin B. Biophys. J. 1994;66:2166–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)81012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Needham D., Hochmuth R.M. A sensitive measure of surface stress in the resting neutrophil. Biophys. J. 1992;61:1664–1670. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81970-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Evans E., Yeung A. Apparent viscosity and cortical tension of blood granulocytes determined by micropipet aspiration. Biophys. J. 1989;56:151–160. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garcia P.D., Guerrero C.R., Garcia R. Time-resolved nanomechanics of a single cell under the depolymerization of the cytoskeleton. Nanoscale. 2017;9:12051–12059. doi: 10.1039/c7nr03419a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sung K.L., Sung L.A., Chien S. Dynamic changes in viscoelastic properties in cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated killing. J. Cell Sci. 1988;91:179–189. doi: 10.1242/jcs.91.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lipowsky H.H., Riedel D., Shi G.S. In vivo mechanical properties of leukocytes during adhesion to venular endothelium. Biorheology. 1991;28:53–64. doi: 10.3233/bir-1991-281-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang N., Tolić-Nørrelykke I.M., Stamenović D. Cell prestress. I. Stiffness and prestress are closely associated in adherent contractile cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C606–C616. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00269.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.MacKay J.L., Keung A.J., Kumar S. A genetic strategy for the dynamic and graded control of cell mechanics, motility, and matrix remodeling. Biophys. J. 2012;102:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang N., Naruse K., Ingber D.E. Mechanical behavior in living cells consistent with the tensegrity model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:7765–7770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141199598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stamenović D., Liang Z., Wang N. Effect of the cytoskeletal prestress on the mechanical impedance of cultured airway smooth muscle cells. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92:1443–1450. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00782.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shroff S.G., Saner D.R., Lal R. Dynamic micromechanical properties of cultured rat atrial myocytes measured by atomic force microscopy. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:C286–C292. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Étienne J., Fouchard J., Asnacios A. Cells as liquid motors: mechanosensitivity emerges from collective dynamics of actomyosin cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2740–2745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417113112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mitrossilis D., Fouchard J., Asnacios A. Single-cell response to stiffness exhibits muscle-like behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18243–18248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903994106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simon S.I., Schmid-Schönbein G.W. Biophysical aspects of microsphere engulfment by human neutrophils. Biophys. J. 1988;53:163–173. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lomakin A.J., Lee K.C., Danuser G. Competition for actin between two distinct F-actin networks defines a bistable switch for cell polarization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:1435–1445. doi: 10.1038/ncb3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fritzsche M., Fernandes R.A., Eggeling C. Cytoskeletal actin dynamics shape a ramifying actin network underpinning immunological synapse formation. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1603032. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yeung A., Evans E. Cortical shell-liquid core model for passive flow of liquid-like spherical cells into micropipets. Biophys. J. 1989;56:139–149. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82659-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tsopoulidis N., Kaw S., Fackler O.T. T cell receptor-triggered nuclear actin network formation drives CD4+ T cell effector functions. Sci. Immunol. 2019;4:eaav1987. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]