Abstract

Background

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) involves platelet activation and aggregation caused by heparin or HIT antibodies associated with poor survival outcomes. We report a case of HIT that occurred after hemodialysis was started for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN), which was caused by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV), and ultimately resulted in asymptomatic cerebral infarction.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old Japanese man was urgently admitted to our hospital for weight loss and acute kidney injury (serum creatinine: 12 mg/dL). Hemodialysis therapy was started using heparin for anticoagulation. Blood testing revealed elevated titers of myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and renal biopsy revealed crescentic glomerulonephritis with broad hyalinization of most of the glomeruli and a pauci-immune staining pattern. These findings fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for microscopic polyangiitis, and the patient was diagnosed with RPGN caused by AAV. Steroid pulse therapy, intermittent pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide, and oral steroid therapy failed to improve the patient’s renal function, and maintenance dialysis was started. However, on day 15, his platelet count had decreased to 47,000/µL, with clotting observed in the hemodialysis catheter. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head identified acute asymptomatic brain infarction in the left occipital lobe, and a positive HIT antibody test result supported a diagnosis of type II HIT. During hemodialysis, the anticoagulant treatment was changed from heparin to argatroban. Platelet counts subsequently normalized, and the patient was discharged. A negative HIT antibody test result was observed on day 622.

Conclusions

There have been several similar reports of AAV and HIT co-existence. However, this is a rare case report on cerebral infarction with AAV and HIT co-existence. Autoimmune diseases are considered risk factors for HIT, and AAV may overlap with other systemic autoimmune diseases. To confirm the relationship between these two diseases, it is necessary to accumulate more information from future cases with AAV and HIT co-existence. If acute thrombocytopenia and clotting events are observed when heparin is used as an anticoagulant, type II HIT should always be considered in any patient due to its potentially fatal thrombotic complications.

Keywords: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, Cerebral infarction, Autoimmune disease, Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, Heparin, Nafamostat, Argatroban

Background

Heparin is the most commonly used anticoagulant agent during hemodialysis because of its cost-effectiveness. However, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) can develop via an immunological response after the start of heparin treatment and reportedly occurs in 3.9 % of patients during the introductory phase of hemodialysis therapy, which frequently causes fatal thrombotic complications [1]. Furthermore, the development of HIT is associated with increased mortality among hemodialysis patients [2].

Cases of HIT can be classified as type I and type II [3]. Type I HIT is related to direct platelet stimulation by heparin, without an immune-related mechanism, leading to a mild decrease in the platelet count at 1–2 days after starting the heparin treatment. However, type I HIT is generally not problematic, as it is not associated with thromboembolic complications, and the platelet counts spontaneously normalize.

Type II HIT is caused by antibodies that recognize the platelet factor 4-heparin complex (HIT antibodies), and it is relatively rare (0.5–5 % of heparin-treated cases) [4]. HIT antibodies cause the activation of platelets, monocytes, vascular endothelial cells, and coagulation factors, resulting in the overproduction of thrombin, and ultimately, thrombopenia and thrombosis [5]. Moreover, patients often develop serious complications that are related to arteriovenous thrombosis and embolism [6]. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were firstly reported in 1982 as a group of autoantibodies, mainly of the IgG type, against antigens in the cytoplasm of neutrophil granulocytes [7].

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a group of relatively rare autoimmune diseases of unknown cause characterized by inflammation of blood vessels and the detection of ANCA in the blood. According to the European League Against Rheumatism [8], AAV has features of inflammation, vasculitis, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN), characteristic renal biopsy findings such as crescent formation, and/or ANCA-positive results. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) are included in AAV. Herein, we report a rare case of type II HIT that occurred after hemodialysis therapy was started for RPGN, which was caused by AAV, and ultimately resulted in asymptomatic cerebral infarction.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old Japanese man presented with a chief complaint of general fatigue, as well as weight loss that began in July 2018. He visited a nearby clinic in October 2018 because of his general fatigue and was referred to our hospital because of severe renal dysfunction (serum creatinine: 12 mg/dL). The patient was previously healthy with no notable medical or family history, including no history of allergy. He had smoked 30 cigarettes/day for approximately 55 years and occasionally consumed alcohol.

Physical examination revealed a height of 157 cm, a weight of 44.6 kg, body mass index of 18.1 kg/m2, blood pressure of 162/77 mmHg, heart rate of 89 beats/min, and body temperature of 36.6 °C. The patient was lucid and had signs of anemia at the palpebral conjunctiva, but no signs of jaundice at the bulbar conjunctiva. Furthermore, we did not observe any significant findings during examinations of the oral cavity, cervical lymph nodes, cardiopulmonary sounds, abdomen, bilateral costovertebral angle, feet, joints, skin, or related neurological findings.

The blood and urine test results obtained on admission are shown in Table 1. The blood tests revealed severe renal dysfunction, anemia, and elevated levels of C-reactive protein and myeloperoxidase ANCA. The urinalysis revealed positivity for protein and occult blood. Computed tomography revealed evidence of interstitial pneumonia in the posterior segments of the bilateral lower lobes and mild bilateral kidney enlargement, suggesting acute kidney injury. Based on these findings, the patient was urgently admitted for treatment.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings from the admission

| Urinalysis | Biochemistry, immunological, virologic, and coagulation parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 3+ | TP | 6.9 g/dL | Ferritin | 499 ng/mL |

| Occult blood | 3+ | Alb | 3.3 g/dL | IgG | 1,674 mg/dL |

| Red blood cells | > 100/HPF | UA | 8.3 mg/dL | IgA | 296 mg/dL |

| Protein | 5.72 g/gCr | BUN | 134.2 mg/dL | IgM | 69 mg/dL |

| NGAL | 1485 ng/mL | Cr | 13.96 mg/dL | C3 | 79 mg/dL |

| NAG | 17.8 U/L | eGFR | 3 mL/min/1.73 m2 | C4 | 27.3 mg/dL |

| α1MG | 91.8 mg/L | TB | 0.1 mg/dL | CH50 | 43 U/mL |

| β2MG | 37,676 µg/L | AST | 6 IU/L | Antinuclear Ab | 1:40 |

| Bence Jones protein | – | ALT | 10 IU/L | Anti-dsDNA Ab | – |

| Complete blood cell count | ALP | 249 IU/L | Anti-smith Ab | – | |

| White blood cells | 6,300/µL | γ-GT | 16 IU/L | Anti-CL-β2GP1 Ab | – |

| Neutrophils | 75.10 % | LDH | 166 IU/L | Direct Coombs test | – |

| Lymphocytes | 13.30 % | CK | 64 IU/L | Anti-MPO-ANCA | 1,700 IU/mL |

| Monocytes | 5.90 % | Na | 134 mEq/L | Anti-PR3-ANCA | – |

| Eosinophils | 5.20 % | K | 6.3 mEq/L | Cryoglobulin | – |

| Red blood cells | 238 × 104/µL | Cl | 102 mEq/L | HIV Ag/Ab | – |

| Hemoglobin | 7.5 g/dL | cCa | 7.7 mg/dL | HBs Ag/HBc Ab | – |

| Hematocrit | 22.60 % | IP | 7.3 mg/dL | HCV Ab | – |

| Platelets | 15.8 × 104/µL | CRP | 2.47 mg/dL | PT | 94 % |

| TC | 147 mg/dL | APTT | 24.9 s | ||

| TG | 220 mg/dL | D-dimer | 4.1 µg/mL | ||

| HbA1c | 5.40 % | ||||

| HANP | 340.6 pg/mL | ||||

| BNP | 140.0 pg/mL | ||||

NAG N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase, NAGL NAG ligand, α1MG alpha1-microglobulin, β2MG beta2-microglobulin, TP total protein, Alb albumin, UA uric acid, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Cr creatinine, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, AST aspartate transaminase, ALT alanine transaminase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, γ-GT gamma-glutamyl transferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CK creatine kinase, CRP C-reactive protein, TC total cholesterol, TG triglycerides, HBa1c glycated hemoglobin, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, PT prothrombin time, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time

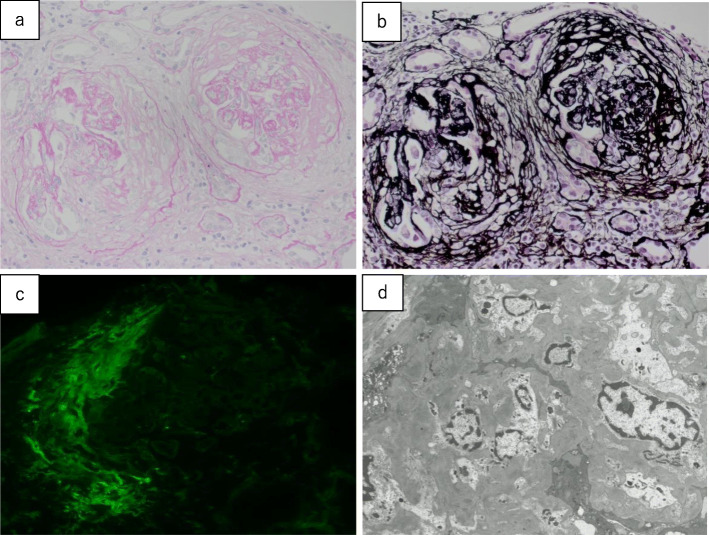

Hemodialysis was started for acute kidney injury on day 1 using heparin as an anticoagulant. Renal biopsy was performed on day 7, which revealed that 3 of 15 glomeruli were completely hyalinized, and the remaining 12 glomeruli were mostly hyalinized, with crescent formation and transitioning to fibrous crescents, as well as collapsed and destroyed glomerular loops (Fig. 1). Lymphocyte infiltration was observed in the tubulointerstitium, and 60–70 % of all renal tubules were atrophied. Immunostaining revealed a pauci-immune pattern, and these findings fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for MPA. Thus, the patient was diagnosed with RPGN related to acute kidney injury caused by AAV.

Fig. 1.

Renal biopsy findings. a Periodic acid-Schiff staining (40×), b periodic acid-methenamine silver staining (40×), c immunostaining for fibrinogen, and d electron microscopy findings (2,000×). Fifteen glomeruli (3 were completely hyalinized, and 12 were mostly hyalinized) exhibit evident crescent formation, with transitioning to fibrous crescents. The glomerular loops are collapsed and destroyed with fibrin deposition. Expansion of the mesangial matrix and an increase in the mesangial cell count are observed, although no double contours or spike formation of the glomerular basement membranes are observed. Lymphocyte infiltration is evident in the tubular interstitium, and 60–70 % of all renal tubules are atrophied. Moderate arteriosclerosis resulting from intimal thickening and medial atrophy is observed in the interlobular arteries (a, b). Immunofluorescence failed to detect the expression of IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C4, or C1q, and only fibrinogen expression is observed in the crescents (c). Electron microscopy reveals no electron-dense deposits, and podocyte degeneration is observed with evident disappearance of the podocyte foot processes (d)

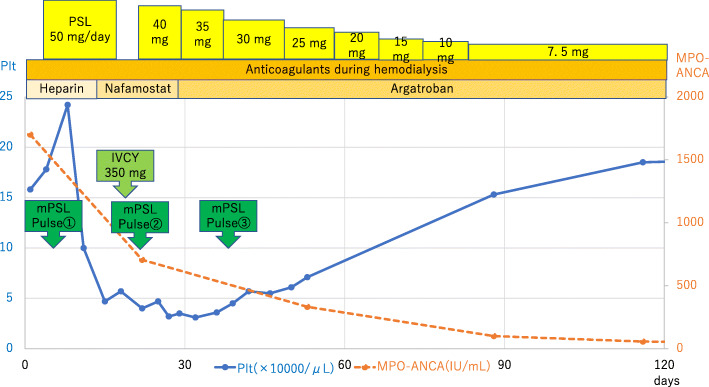

The Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score was 18, and no alveolar hemorrhage or neurological symptoms were observed. The patient was treated using three sessions of steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone at 1,000 mg/day), one session of intermittent intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse (IVCY) therapy (because we considered avoiding aggressive immunosuppression since the kidney biopsy results showed more chronic changes and fibrosis/atrophy than the active disease), and oral steroid therapy (prednisolone at 50 mg/day) (Fig. 2). However, the patient’s renal function did not improve, and maintenance dialysis was started.

Fig. 2.

The treatment course and changes in platelet count over time. The treatments involved steroid therapy with prednisolone (PSL), anticoagulant treatment during hemodialysis, intravenous cyclophosphamide (IVCY) therapy, and steroid pulse therapy with methylprednisolone (mPSL). The laboratory test parameters were changes in myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (MPO-ANCA) titers (red) and platelet counts (blue). The platelet counts improved after argatroban was started as anticoagulant treatment during hemodialysis

On day 15, clotting was observed in the hemodialysis catheter. Complete blood count with biochemical parameters was performed as a follow-up to assess anemia and the state of AAV after steroid pulse therapy revealed a drastic drop in the patient’s platelet count to 47,000/µL without elevated levels of C-reactive protein. HIT related to hemodialysis using heparin was strongly suspected, and D-Dimer with other coagulation parameters were evaluated to assess diseases causing thrombocytopenia. The D-dimer concentration had increased acutely to 22.7 µg/mL up from 4.1 µg/mL on admission despite the negative level of C-reactive protein after AAV treatment suggesting improvement of AAV. Because type II HIT can potentially cause critical thrombosis, physical and image examinations were performed based on a suspicion of thrombosis.

The patient was lucid after hemodialysis initiation, symptoms were absent, and vital signs were as follows: blood pressure of 133/68 mmHg, heart rate of 67 beats/min, body temperature of 36.2 °C, and oxygen saturation of 99 %. Regarding physical findings, no findings of vision loss, restricted visual field, abnormal cardiopulmonary sounds, abdominal pain, and livedo reticularis were observed. The pulse of the bilateral radial arteries and the bilateral dorsalis pedis artery were normal. There were no findings of motor paralysis, sensory disorders, gait disturbance, dysarthria, aphasia, and unilateral spatial neglect. No significant neurological findings were observed, and no findings of thromboembolism were observed in the trunk or limbs. However, we performed head magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography of the trunk to establish differential diagnoses of thrombosis, inflammatory disease, and chronic diseases related to acute thrombocytopenia with an increase in D-dimer concentration and clotting in the hemodialysis catheter. This is because we consider that AAV is often accompanied by thrombosis and is rarely accompanied by cerebral aneurysm or arterial stenosis resulting from vasculitis. Moreover, thrombosis could similarly be caused by type II HIT.

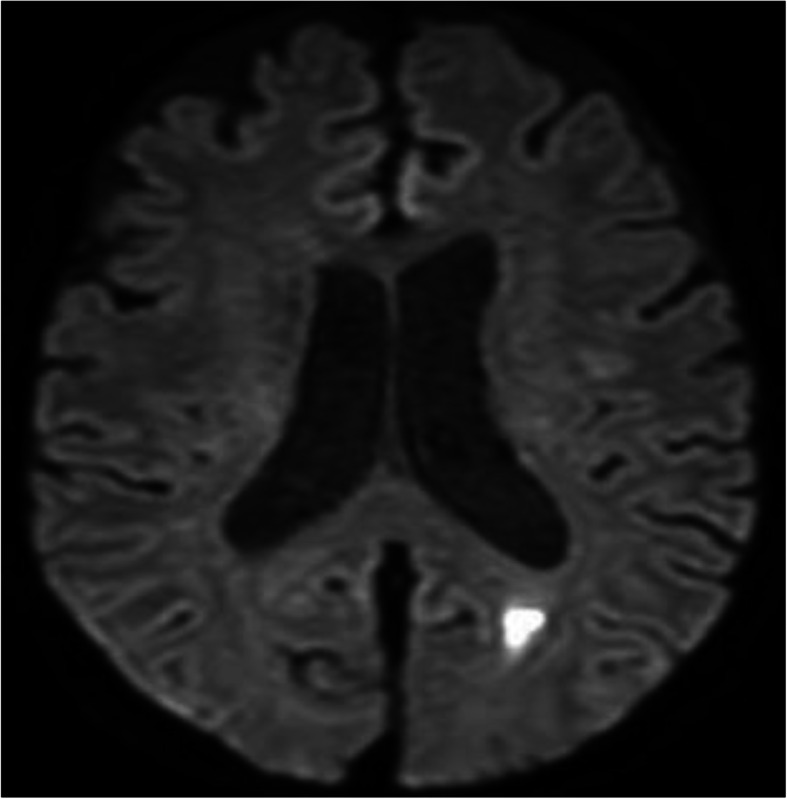

Consequently, acute asymptomatic cerebral infarction was observed in the left occipital lobe without findings of vasculitis in cerebral arteries during head magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 3). In contrast, computed tomography of the trunk revealed no findings of thrombosis, inflammatory disease, and chronic diseases. Thus, HIT was suspected based on the decreased platelet count after starting heparin treatment and the development of asymptomatic cerebral infarction, as well as clotting in the hemodialysis catheter. Disseminated intravascular coagulation was considered unlikely based on the absence of infection or malignant tumors, and thrombotic microangiopathy was considered unlikely based on the haptoglobin value being within the normal range. Furthermore, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura was considered unlikely based on the negative results for anti-platelet antibodies (Table 2), and there was no atrial fibrillation. However, a high likelihood of HIT was judged based on the HIT scoring system (a 4Ts score of 6) [9], and the presence of HIT antibodies on day 15 supported a diagnosis of asymptomatic cerebral infarction caused by type II HIT (Table 2). Because there was no bleeding lesion in the brain, the patient was treated using aspirin (200 mg/day).

Fig. 3.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the head reveals a high-intensity signal in the left occipital-temporal lobe, which indicates acute cerebral infarction

Table 2.

Laboratory findings from day 15

| Platelets | 4.7 × 104/µL |

| CRP | < 0.3 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 22.7 µg/mL |

| Haptoglobin | 160 mg/dL |

| Anti-thrombocyte antibodies | − |

| Anti-platelet factor 4-heparin complex antibodies | +, 5.6 U/mL |

CRP C-reactive protein

After thrombocytopenia was confirmed, the anticoagulant treatment during hemodialysis was changed from heparin to nafamostat on day 15, which we have commonly used for patients in whom heparin is contraindicated. However, the platelet count did not begin to recover until after the anticoagulant treatment was changed from nafamostat to argatroban on day 29. The platelet counts gradually improved, and the patient was discharged on day 51, with argatroban treatment during the subsequent hemodialysis. The patient did not experience any vascular events after the discharge, and a negative result was observed for a second HIT antibody test that was performed on day 622.

Discussion and conclusions

This report describes our experience with a case of type II HIT that occurred after hemodialysis therapy was started for RPGN, which was caused by AAV, and ultimately resulted in asymptomatic cerebral infarction. Asymptomatic cerebral infarction was probably caused by either HIT or AAV, or a combination of both, because they both evidently induce arteriolar infarction. However, because this is diagnosed as acute cerebral infarction with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the head without findings of vasculitis in the cerebral arteries and with negative levels of C-reactive protein after AAV treatment suggesting improvement of AAV, we consider that this asymptomatic cerebral infarction was more likely caused by type II HIT than by AAV.

The principal stroke mechanism of posterior cerebral artery (PCA) infarction was suggested to be cardioembolic (54.1 %) in the superficial PCA territory, lacunar (46.2 %) in the proximal PCA territory, and undetermined (40.2 %) in both the proximal and the superficial territories; thus, we believe that the mechanism underlying cerebral infarction in this case is “undetermined” [10]. The patient’s platelet count improved after heparin was replaced with argatroban as the anticoagulant. In this context, type II HIT is caused by antibodies that bind to the platelet factor 4-heparin complex and form an immune complex, which leads to platelet activation and a hypercoagulable state that causes arterial and venous thrombosis [9, 11]. The emergence of HIT typically occurs 5–14 days after the start of heparin treatment, and thrombocytopenia usually resolves 7–10 days after the discontinuation of heparin treatment. Clinical suspicion of HIT is based on a sharp decrease in platelet counts during heparin treatment, which generally resolves after the heparin is discontinued. The diagnosis of HIT is based on a clinical scoring system [12, 13] and serologically supported by the detection of HIT antibodies [14]. The differential diagnoses of HIT include other pathological conditions that cause thrombocytopenia during the acute phase of AAV, such as thrombotic microangiopathy [15], non-heparin drug-induced thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation caused by infection.

The treatment of HIT involves complete cessation of heparin treatment during hemodialysis, with a switch to argatroban (an antithrombin drug) [9, 16]. Nafamostat may be an alternative anticoagulant agent during hemodialysis; however, it cannot suppress the hypercoagulable state induced during the acute phase of HIT and does not help improve platelet counts. Therefore, in Japan, argatroban is a more desirable and established anticoagulant agent for use during the acute phase of HIT. However, HIT antibodies only exist temporarily and reportedly become undetectable at 50–85 days after the discontinuation of heparin [17]. When the HIT antibodies become undetectable, nafamostat and argatroban can be used as anticoagulant agents during maintenance dialysis. In addition, re-administering heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin while monitoring for HIT antibodies did not cause HIT recurrence [18–20]. Although immunosuppressive therapy is rarely used for HIT, there was one reported case of refractory HIT treated using plasma exchange and rituximab [21]. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin may also be an effective adjunct to anticoagulation treatment for HIT [22].

Although HIT and AAV have different etiologies, HIT is thought to involve autoimmune mechanisms, as its pathophysiology is related to the production of immune complexes. Titers of HIT antibodies (IgM, IgA, and IgG) increase simultaneously from the fifth day after the start of heparin treatment [23], and HIT IgG antibodies activate platelets, monocytes, and vascular endothelial cells, leading to the development of HIT [24]. Thus, HIT may involve a mechanism that is different from a normal antigen-antibody reaction. Furthermore, HIT is significantly more common among patients undergoing hemodialysis and those with autoimmune diseases, as autoimmune diseases are reportedly a risk factor for HIT because of abnormal immune complex production [25]. Moreover, there are statistically significant associations between the prevalence of HIT and several autoimmune diseases, including antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and nonischemic cardiomyopathy [26]. Thus, although the association between HIT and autoimmune disease is not clearly understood, the development of an autoimmune disease and HIT may have some commonalities. First, HIT requires the formation of a specific “neoantigen” (the heparin-platelet factor 4 complex), which is similar to the citrullinated proteins that are central to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis [27, 28]. Second, IgG antibodies that bind this complex can be detected for some period of time, similar to the post-vaccination Arthus reaction (type III hypersensitivity reaction) [29]. Because the most frequent autoimmune disease associated with AAV is rheumatoid arthritis, followed by the other systemic autoimmune diseases [30], AAV may be related to these mechanisms. Although the co-occurrence of AAV and HT is rare, a search of the PubMed database revealed several reports of HIT that occurred at the start of hemodialysis therapy for AAV, which is similar to that in the present case [31–35] (Table 3). Regarding the clinical characteristics of the six cases of coexistent AAV and HIT, including this case, all cases involved immunosuppressive therapy and used unfractionated heparin for dialysis or prevention of deep vein thrombosis. The onset of HIT from heparin use was 10.7 ± 3.6 days. Five of six patients had thrombotic or clotting events, and five of six patients were treated with argatroban for HIT. However, the present case is a rare case report of asymptomatic cerebral infarction with AAV and HIT co-existence.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of six cases of coexisting AAV and HIT, including this case

| Literature | Age | Sex | Type of ANCA | Organ injury | Treatment for AAV | Onset of HIT | Type of heparin | Thrombotic event | Treatment for HIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roe et al. [31]. | 65 | M | PR3 |

Crescentic glomerulonephritis Pulmonary hemorrhage |

mPSL pulse, PSL, CY Hemodialysis |

9 days after the start of hemodialysis | Unfractionated heparin |

Deep venous thrombosis |

Danaparoid |

| Kaneda et al. [32]. | 91 | F | MPO |

Kidney dysfunction Pulmonary hemorrhage |

mPSL pulse, PSL, Hemodialysis |

13 days after the start of hemodialysis | Unfractionated heparin | N/A | Argatroban |

| Mandai et al. [33]. | 40 | M | MPO |

Crescentic glomerulonephritis Interstitial pneumonia |

mPSL pulse, PSL, CY, PE, Hemodialysis |

5 days after the start of hemodialysis | Unfractionated heparin | Clotting in hemodialysis catheter | Argatroban |

| Thong et al. [34]. | 71 | M | PR3 | Kidney dysfunction |

mPSL pulse, PSL, CY, Hemodialysis |

15 days after the start of hemodialysis | Unfractionated heparin | Circuit and catheter clotted | Argatroban |

| Nonaka et al. [35]. | 87 | F | MPO | Kidney dysfunction |

PSL Hemodialysis |

8 days after the start for prevention of deep vein thrombosis | Unfractionated heparin | Deep venous thrombosis | Argatroban |

| This case | 76 | M | MPO |

Crescentic glomerulonephritis Interstitial pneumonia |

mPSL pulse, PSL, CY Hemodialysis |

14 days after the start of hemodialysis | Unfractionated heparin |

cerebral infarction Clotting in hemodialysis catheter |

Aargatroban |

ANCA Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, AAV anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, HIT heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, PR3 proteinase 3, MPO myeloperoxidase, mPSL methylprednisolone, PSL prednisolone, CY cyclophosphamide, PE plasma exchange

Most patients in these reported cases had received immunosuppressive therapy, but only developed HIT after starting hemodialysis for AAV-induced renal failure. Therefore, the immunosuppressive therapy may not suppress the production of antibodies that target the platelet factor 4-heparin complex. However, no reports have examined the relationship between AAV and HIT, and the precise reason for the co-existence of these two diseases is poorly understood. Nevertheless, HIT causes thromboembolic diseases in approximately 20–50 % of patients [6] and has a mortality rate of approximately 5 % [36]. Moreover, AAV is a significant risk factor for deep vein thrombosis [9, 37, 38].

In conclusion, there are several reports regarding the co-existence of AAV and HIT. To confirm the relationship between these two diseases, it is necessary to conduct further studies on cases with AAV and HIT co-existence. If acute thrombocytopenia and clotting events are observed when heparin is used as an anticoagulant, type II HIT should always be considered in any patient due to its potentially fatal thrombotic complications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- AAV

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis

- ANCA

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

- PCA

Posterior cerebral artery

- RPGN

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

Authors’ contributions

YF, MK, JY, TY, AN, RI, HT, and YS provided medical treatment for the patient. YF conceived and designed the report. YF acquired the data. YF drafted the manuscript. YF critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the manuscript version to be published. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yamamoto S, Koide M, Matsuo M, Suzuki S, Ohtaka M, Saika S, Matsuo T. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in hemodialysis patients. Am J Dis. 1996;28:82–5. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(96)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrier M, Rodger MA, Fergusson D, Doucette S, Kovacs MJ, Moore J, et al. Increased mortality in hemodialysis patients having specific antibodies to the platelet factor 4-heparin complex. Kidney Int. 2008;73:213–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong BH. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1471–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong BH, Berndt MC. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 1989;58:53–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00320647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brieger DB, Mak KH, Kottke-Marchant K, Topol EJ. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1449–59. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00134-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arepally GM, Ortel TL. Clinical practice. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:809–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies DJ, Moran JE, Niall JF, Ryan GB. Segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis with antineutrophil antibody: possible arbovirus aetiology? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6342.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellmich B, Flossmann O, Gross WL, Bacon P, Cohen-Tervaert JW, Guillevin L, et al. EULAR recommendation for conducting studies and/or clinical trials in systemic vasculitis focus on anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:605–17. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsh J, Heddle N, Kelton JG. Treatment of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a critical review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:361–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander BM, Daniel CB, Julien B. Posterior cerebral artery infarction from middle cerebral artery infarction. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:938–41. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davenport A. Antibodies to heparin-platelet factor 4 complex: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:361–74. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo GK, Juhl D, Warkentin TE, Sigouin CS, Eichler P, Greinacher A. Evaluation of pretest clinical score (4T’s) for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in two clinical settings. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:759–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warkentin TE. How I diagnose and manage HIT. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program Book. 2011;2011:143–9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Althaus K, Hron G, Strobel U, Abbate R, Rogolino A, Davidson S, et al. Evaluation of automated immunoassays in the diagnosis of heparin induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb Res. 2013;131:e85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagai K, Kotani T, Takeuchi T, Shoda T, Hata-Kobayashi A, Wakura D, et al. Successful treatment of thrombocytopenic purpura with repeated plasma exchange in a patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:643–6. doi: 10.3109/s10165-008-0107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis BE, Wallis DE, Berkowitz SD, Matthai WH, Fareed J, Walenga JM, et al. Argatroban anticoagulant therapy in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Circulation. 2001;103:1838–43. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.14.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warkentin TE, Kelton JG. Temporal aspects of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1286–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuo T, Kusano H, Wanaka K, Ishihara M, Oyama A. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in a uremic patient requiring hemodialysis: an alternative treatment and reexposure to heparin. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2007;13:182–7. doi: 10.1177/1076029606298996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartman V, Malbrain M, Daelemans R, Meersman P, Zachee P. Pseudo-pulmonary embolism as sign of acute heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in hemodialysis patients: safety of resuming heparin after disappearance of HIT antibodies. Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;104:143–8. doi: 10.1159/000094959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeEugenio DL, Ruggiero NJ, Thomson LJ, Menajovsky LB, Herman JH. Early-onset heparin-induced thrombocytopenia after a 165-day heparin-free interval. case report and review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:615–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.4.615.61036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schell M, Petras M, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Ornstein DL. Refractory heparin induced thrombocytopenia with thrombosis (HITT) treated with therapeutic plasma exchange and rituximab as adjuvant therapy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2013;49:185–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warkentin TE. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a review. Expert Rev Hematol. 2019;12:685–98. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2019.1636645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greinacher A, Kohlmann T, Strobel U, Sheppard JA, Warkentin TE. The temporal profile of the anti-PF4/heparin immune response. Blood. 2009;113:4970–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warkentin TE, Sheppard JA, Moore JC, Cook RJ, Kelton JG. Studies of the immune response in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2009;113:4963–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato S, Takahashi K, Ayabe K, Samad R, Fukaya E, Friendmann P, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: analysis of risk factor in medical in-patients. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:373–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klinkhammer B, Gruchalla M. Is there an association between heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and autoimmune disease? WMJ. 2018;117:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai Z, Zhu Z, Greene MI, Cines DB. Atomic features of an autoantigen in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:752–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vossenaar ER, van Venrooij WJ. Citrullinated proteins: sparks that may ignite the fire in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:107–11. doi: 10.1186/ar1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salter BS, Weiner MM, Trinh MA, Heller J, Evans AS, Adams DH, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a comprehensive clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2519–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martín-Nares E, Zuñiga-Tamayo D, Hinojosa-Azaola A. Prevalence of overlap of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis with systemic autoimmune diseases: an unrecognized example of poliautoimmunity. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roe SD, Cassidy MJ, Haynes AP, Byrne JL. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and thrombosis in a haemodialysis-dependent patient with systemic vasculitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:3226–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.12.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneda K, Fukunaga N, Kudou A, Ohno E, Imagawa Y, Ohishi K, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) in an acute uremic patient with ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. Nihon Toseki Igakkai Zasshi. 2009;42:453–8. doi: 10.4009/jsdt.42.453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandai S, Nagahama K, Tsuura Y, Hirai T, Yoshioka W, Takahashi D, et al. Recovery of renal function in a dialysis-dependent patient with microscopic polyangiitis and both myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies. Intern Med. 2011;50:1599–603. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thong KM, Toth P, Khwaja A. Management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) in patients with systemic vasculitis and pulmonary haemorrhage. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6:622–5. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sft075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nonaka T, Harada M, Sumi M, Ishii W, Ichikawa T, Kobayashi M. A case of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia that developed in the therapeutic course of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2019;2019:2724304. doi: 10.1155/2019/2724304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, Koster A, Lincoff AM. Treatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133:340S-80S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Kang A, Antonelou M, Wong NL, Tanna A, Arulkumaran N, Tam FWK, et al. High incidence of arterial and venous thrombosis in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:285–93. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stassen PM, Derks RP, Kallenberg CG, Stegeman CA. Venous thromboembolism in ANCA-associated vasculitis-incidence and risk factors. Rheumatology. 2008;47:530–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.