(See the Major Article by Inghammar et al on pages e1084–9.)

The association between proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) has been troubling clinicians, epidemiologists, and basic scientists for almost 20 years since its discovery [1]. PPIs are the victims of their success. Their unparalleled efficacy for treating gastroesophageal reflux disease, erosive esophagitis, and peptic ulcer disease, along with a rather benign safety profile, has placed them among the most widely used and prescribed medication categories. Their extensive use, perhaps sometimes unjustified, is concentrated in people experiencing a vast array of symptoms, including even sore throat, chronic cough, tooth decay, vague abdominal discomfort, among others, who, not unexpectedly, are prone to be facing more health problems than those not using PPIs. Literature associating PPIs to multiple problems ranging from hypomagnesemia [2] to, most recently, coronavirus disease 2019 [3], including dementia [4], stroke, and myocardial infarction [5], has followed. Some of these associations stood the test of time, and others remain controversial to this day [6, 7].

The effects of PPIs in the diversity and composition of the gut microbiota with associated changes in metabolites lend biologic plausibility to the hypothesis of a causal relationship between PPI use and incident CDI [8]. A myriad of observational studies describes the association. Meta-analyses of such studies have, unsurprisingly, shown consistency in this association [9, 10]. Nonetheless, these studies are fraught with bias arising from the choice of control groups with lower baseline risk for CDI and residual confounding if attempts at controlling confounders are even undertaken. Meta-analyses can, unfortunately, serve as amplifiers of bias.

It is in this context that we read with interest Inghammar et al’s article in this issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases [11]. The authors present a smoothly written article that addresses PPIs and incident CDI, on this occasion in the community setting. To this end, they leverage the country-wide Danish database with a relatively newer observational method, the self-controlled case series (SCCS). This method includes patients with the outcome of interest (in this case, CDI) and then identifies the periods of exposure and nonexposure to the risk factor of interest (in this case, PPI use). The measure of association is the ratio between the incidences of the event in the exposed period and the unexposed period. The main advantage of SCCS is that every patient will be its control, thus eliminating sources of confounding that may not vary over time (time-independent confounders).

Briefly, 3583 cases of primary community-acquired adult CDI cases were identified over 4 years based on a centralized microbiology database. PPI exposure is defined based on centralized outpatient pharmacy prescription and filling data. Confounders such as age, gender, antibiotic and steroid exposure, and hospitalization are either adjusted for or addressed via sensitivity or subgroup analyses. The main finding is an adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 2.03 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.74–2.36) for CDI in PPI-exposed individuals. Also, the IRRs for the two 6-month periods chronologically following PPI use are provided and remain significant (IRR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.31–1.80 and IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.00–1.53).

This study has multiple strengths. First, the use of a centralized national database allows for population-level data that minimizes selection bias, loss to follow-up, and unmeasured exposures to PPI or other coexposures such as to antibiotics. Second, the SCCS design eliminates time-independent unmeasured covariables, so chronic conditions that affect CDI risk, such as chronic kidney failure, quiescent inflammatory bowel disease, or chronic immunosuppression are accounted for by design. Third, the authors carefully adjusted for some known time-dependent coexposures such as to antibiotics, corticosteroids, and hospitalization; 2 sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses for age and gender prove their findings robust.

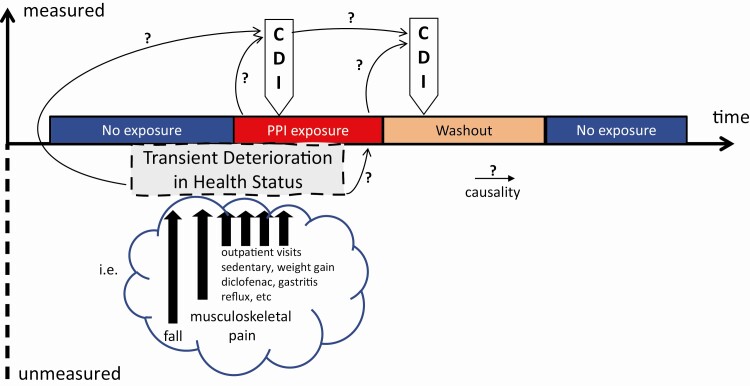

The study also has some limitations. First, while the SCCS design intrinsically controls for time-independent confounding and the authors controlled for some time-dependent confounding factors, many plausible health events may increase the risk of CDI and can be associated with PPI prescription or use. CDI tends to occur during periods of deterioration of people’s overall health. If this deterioration is profound, it may be captured by hospitalization. However, if this deterioration of overall health is significant enough to predispose to CDI and PPI use but transient, then we have unmeasured confounding. Figure 1 illustrates this concept and presents an example. To the authors’ credit, such events are difficult to capture, and adding multiple confounders to a model can lead to complex interactions or overfitting. While there is no perfect solution to this problem, accounting for polypharmacy or having a “negative control” drug (with no known or plausible association with CDI, that is, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory, statin) could lend more support to the conclusions. Second, there are missed opportunities of strengthening the study by leveraging the centralized national database, such as refining the CDI definition by including treatment with oral metronidazole, vancomycin or fidaxomicin; refining the indication of PPI prescription such as indication by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10 code); and refining the context of PPI prescription to account for other exposures or risk factors for CDI co-occurring. This could be achieved by the number of coprescription, the number of outpatient visits, and the number of other ICD-10 codes during the exposure period surrounding the event.

Figure 1.

Model for confounding despite the self-controlled case series design. Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

Taking all this into account, Inghammar et al’s study, with its many strengths, does not fully settle the question. Ideally, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) could bring a definitive answer. An ad hoc trial for this question would face multiple barriers, however. CDI event rates are low in the community; such a trial would require a large study population or focus on high-risk individuals, which could hinder its generalizability. Also, it may not be easy to recruit into a trial in which a potential side effect is being studied. Table 1 summarizes all the recent RCTs for PPIs where CDI has been a secondary outcome [12–16]. While these studies are admittedly underpowered for incident CDI as an outcome, they beg the question of whether such effort and investment should be directed toward a theoretical doubling of event rates from 0.05% to 0.1% [13] (number needed to harm = 200) in the community setting.

Table 1.

Randomized Controlled Trials Involving Proton Pump Inhibitors That Reported Incident Clostridioides difficile Infection as an Outcome

| Clostridioides difficile Infection Rate in | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | Proton Pump Inhibitor Group | Comparator Group | Comparator | Association Measure | Year | Author |

| ICU, ventilated | 40 of 13415 (0.30%) | 57 of 13392 (0.43%) | Histamine receptor 2 antagonists | RR, 0.74 (95% CI, .51–1.09) | 2020 | PEPTIC investigators |

| Community | 9 of 8791 (0.1%) | 4 of 8807 (0.05%) | Placebo | OR, 2.26 (95% CI, .70–7.34) | 2019 | Moayyedi et al |

| ICU | 19 of 1644 (1.2%) | 25 of 1647 (1.5%) | Placebo | RR, 0.76 (95% CI, .42–1.39) | 2018 | Krag et al |

| ICU | 2 of 49 (4.1%) | 1 of 42 (2.4%) | Placebo | RR, 1.71 (95% CI, .16–18.24) | 2016 | Alhazzani et al |

| ICU | 1 of 106 (0.94%) | 0 of 108 (0%) | Placebo | RR, 3.06 (95% CI, .13–74.19) | 2016 | Selvanderan et al |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; PEPTIC, proton pump inhibitors vs histamine-2 receptor blockers for ulcer prophylaxis treatment in the intensive care unit; RR, relative risk.

Despite all controversies surrounding PPI’s proposed side effects, multiple physicians and physician organizations have assumed causality, which is reflected in guidance recommending routine deprescription of PPIs. While attempts at decreasing polypharmacy and unneeded chronic medications are lauded, these efforts, when adopted too aggressively or without in-depth evaluation of PPI indication (which can happen quickly in fractionated healthcare systems such as the United States), may lead to unintended consequences. Furthermore, the acritical reporting of studies describing such associations in the lay media has placed the deprescription in the patient’s hands who, while empowered, may not be appropriately informed for this decision. Table 2 offers vignettes of representative clinical scenarios faced by practicing gastroenterologists; admittedly, there is a paucity of data on how frequently these situations occur.

Table 2.

Unintended Consequences of Proton Pump Inhibitor Deprescription

| Vignette | Indication for PPI | Theoretical Risks | Real Consequence | End Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61-year-old female with 1 episode of CDI after antibiotic course for community-acquired pneumonia | Nonerosive GERD with prior endoscopic evidence of hiatal hernia | ↑CDI recurrence ↑risk of pneumonia | Recurrence of symptomatic GERD Referral to gastroenterology to assess need for PPI Underwent open access EGD prior to referral |

Morbidity Unnecessary procedure Unnecessary referral PPIs were restarted |

| 37-year-old male with chronic kidney disease stage 3, from diabetic nephropathy with worsening renal function and osteopenia | Maintenance of remission for eosinophilic esophagitis with prior food bolus impactions | ↑risk of interstitial nephritis ↑osteoporosis | Recurrence of eosinophilic esophagitis with food bolus impaction Emergent EGD under general anesthesia Small perforation during EGD Admission for observation for 3 days |

Medical emergency Need for emergent procedure Complication of procedure Need for hospitalization PPIs were restarted |

| 52-year-old female who was found to have a small antral ulcer on EGD for abdominal pain, histology positive for Helicobacter pylori | Triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori, including PPI | ↑risk of coronavirus disease 2019, seen in press | After 2 days of treatment, patient discontinued triple therapy Abdominal pain persists Patient could not be convinced to take triple therapy, may consider when Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 vaccine available |

Morbidity Risk of bleeding or perforation |

Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; EGD, esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

In conclusion, Inghammar et al’s study, with an elegant design and incomparable dataset, bring new and valuable information to an age-old debate, which may unfortunately not be settled soon. A pragmatic approach to PPI prescription and deprescription in patients at risk for CDI is warranted in the meantime. Careful prescription at the lowest effective dose and only for the duration of a clear indication is recommended. If needed, deprescription must have a thorough investigation of PPI’s initial indication as a prerequisite, should be done in a shared decision-making context, and should have a careful proactive follow-up for any unintended effects [17].

Notes

Financial support. National Institutes of Health T32DK007760.

Potential conflicts of interest. The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author has submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Cunningham R, Dale B, Undy B, Gaunt N. Proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. J Hosp Infect 2003; 54:243–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. William JH, Danziger J. Proton-pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: current research and proposed mechanisms. World J Nephrol 2016; 5:152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Almario CV, Chey WD, Spiegel BMR. Increased risk of COVID-19 among users of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:1707–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73:410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sehested TSG, Gerds TA, Fosbøl EL, et al. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, dose-response relationship and associated risk of ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction. J Intern Med 2018; 283:268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Villafuerte-Gálvez JA, Kelly CP. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of Clostridium difficile infection: association or causation? Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2018; 34:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaezi MF, Yang YX, Howden CW. Complications of proton pump inhibitor therapy. Gastroenterology 2017; 153:35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Imhann F, Bonder MJ, Vich Vila A, et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut 2016; 65:740–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arriola V, Tischendorf J, Musuuza J, Barker A, Rozelle JW, Safdar N. Assessing the risk of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection with proton pump inhibitor use: a meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37:1408–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao F, Chen CX, Wang M, et al. Updated meta-analysis of controlled observational studies: proton-pump inhibitors and risk of Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 2018; 98:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inghammar M, Svanström H, Voldstedlund M, Melbye M, Hviid A, Mølbak K, Pasternak B. Proton-pump inhibitor use and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile nfection. Clin Infect Dis 2021:ciaa1857. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa185733629099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. PEPTIC Investigators for the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Alberta Health Services Critical Care Strategic Clinical Network, and the Irish Critical Care Trials Group, Young PJ, Bagshaw SM, et al. Effect of stress ulcer prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors vs histamine-2 receptor blockers on in-hospital mortality among ICU patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation: The PEPTIC randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 323:616–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology 2019; 157:682–91.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krag M, Marker S, Perner A, et al. ; SUP-ICU Trial Group . Pantoprazole in patients at risk for gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:2199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alhazzani W, Guyatt G, Alshahrani M, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group . Withholding pantoprazole for stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a pilot randomized clinical trial and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:1121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Selvanderan SP, Summers MJ, Finnis ME, et al. Pantoprazole or Placebo for Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis (POP-UP): randomized double-blind exploratory study. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:1842–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiens E, Kovaltchouk U, Koomson A, Targownik LE. The clinician’s guide to proton-pump inhibitor discontinuation. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019; 53:553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]