Dear editor,

Despite the damage they cause, disasters are a great challenge to the healthcare systems. Those events may be man-made like terrorist attacks or natural like storms and pandemics [1]. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the COVID-19 infection as a pandemic [2]. This pandemic unveiled the lack of resilience of the Healthcare service in Africa [3]. As healthcare facilities, blood banks were worldwide affected by this pandemic [4]. The American Association of blood banks (AABB) published a disaster operations handbook to help blood banks manage such events [5]. Nevertheless, low-middle income countries have not yet reached this level of preparedness, particularly in blood banks. Hence, maintaining the balance between blood demand and supply in a pandemic has been more challenging. On March 20, 2020, the Tunisian government announced a lockdown which impacted greatly on the blood supply. Many papers assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on blood donation have been published. Nonetheless, little data is available on the management of blood banks during this period. The study aim was to evaluate the satisfaction rate of packed red blood cells components (pRBCCsn) requests and assess the local response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Aziza Othmana's (a Tunisian hospital) blood deposit.

Six-week data was retrospectively obtained from the blood deposit records, from March 15 to April 30, 2020. All pRBCCsn requests from the hematology department were included. For each request, the following data were collected: The date of reception of the request; The date of satisfaction (date of reception the pRBCCsn from the Tunisian national center of blood transfusion; The date of transfusion (date of release of the pRBCCsn to the hematology department) and the number of requested and received pRBCCsn. Requests that lacked one of those variables were excluded. Initially nominative assigned pRBCCsn that were reassigned were identified. The request's satisfaction was defined as total if the number of requested pRBCCsn was the same as the received ones, partial if it was less, and unsatisfied if no pRBCCsn were received. The satisfaction time of satisfied requests was defined as the time from the date of reception to the date of satisfaction. The release time of each received pRBCCsn was defined as the duration between the date of satisfaction and the date of transfusion. The global and weekly transfusion rates of satisfactions were also calculated.

Aziza Othmana is a teaching hospital that has the main hematology department in the country. The hematology department includes an emergency, a day hospital, and a hospitalization (including a sterile unit).

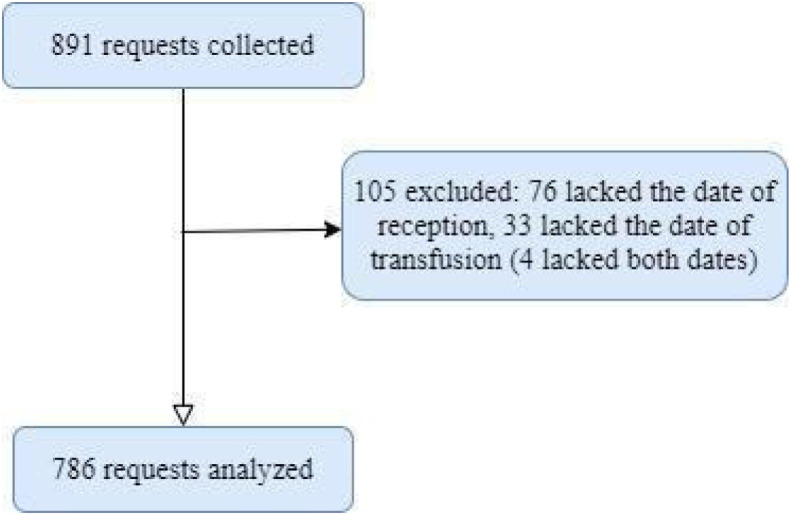

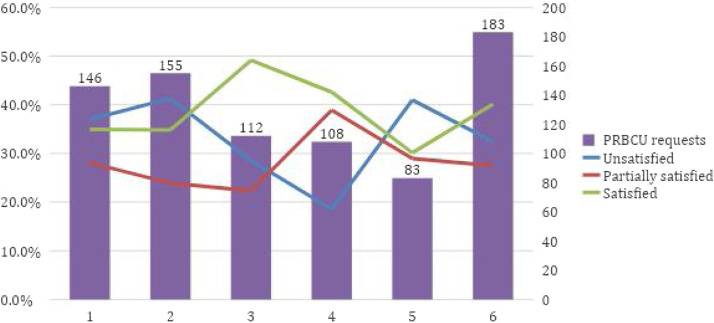

During the six-week study period, 891 PRBCCSN requests were received (Fig. 1 ). One third of the requests (n = 282, 36%) was for more than one unit. Thus, nearly two-thirds of the requests were partially satisfied and unsatisfied (28% and 33% respectively) while only 39% were satisfied (n = 304). During the sixth week, the gap between the number of PRBCCSN requests and blood supply was the most serious, the satisfaction rate was 30.1% (Fig. 2 ). Most satisfied requests (86.8%) were from the day hospital. The time of satisfaction varied from 0 days to 10 days with a median of 0 days. pRBCCsn were within a median of 2 days [0–28]. Seven pRBCCsn were returned to the national center of blood transfusion due to an error in the blood phenotyping while four pRBCCsn expired before being transfused. During the study period, 214 pRBCCsn (27.22%) were reassigned to other patients in urgent need for blood. The satisfaction rate was quite low. However, results should be interpreted cautiously as the study had potential limitations. In fact, the non-digitalization of the blood deposit led to a lack of certain data forcing us to exclude 105 pRBCCsn requests.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Fig. 2.

Weekly variation of satisfaction rate. PRBCU: Packed red blood cell units.

Most patients were in urgent need for blood. Hence, providing such patients with pRBCCsn in a blood shortage context was challenging, as reported in the literature [6]. Indeed, the pRBCCsn requests’ time of satisfaction reached five days leading to a life-threatening delay in transfusion.

In most general hospitals, the delay of non-urgent procedures led to a stabilization of blood supply [7]. In a survey taken in the Eastern Mediterranean region, the estimated decrease of blood supply and demand during the first month of the pandemic, in the Tunisian national blood center was 25% [8]. However, this was not the case for the study site's blood deposit where the satisfaction rate was quite low. This was observed despite the delay of chemotherapy consolidation cures and bone marrow transplant procedures.

In public health, especially in the field of blood transfusion, management practice assessment is a cornerstone [9]. This is especially intriguing in the context of a disaster such as a pandemic. The feedback provided in this paper, may help elaborate a specific plan for disaster management at a local scale and increase emergency blood banks preparedness. When dealing with patients with hematologic disorders, implementing a patient blood management (PBM) strategy proved difficult. Hemoglobinopathies, myelodysplastic syndromes, and hematological malignancies, for example, require frequent transfusions. Patients who receive insufficient blood are vulnerable to the long-term effects of chronic anemia. However, some PBM measures have been shown to be effective.

For instance, adopting a single-unit transfusion strategy in patients with hematologic disorders resulted in reduced pRBCCsn utilization with no increase of the length of stay or mortality [10]. During this study and faced with a scarce blood supply, doctors assessed the patient's clinical state to avoid unnecessary transfusions. When the transfusion decision was made, a single-unit transfusion strategy was preferred. In fact, only one third of the pRBCCsn requests were for more than one unit.

Another reported PBM measure was the use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents. It helped reduce pRBCCsn transfusions in selected myelodysplastic syndromes patients [11]. However, our limited resources did not allow us to prescribe erythropoiesis stimulating agents. Hence, we adopted good practice measures in order to manage the scarce blood supply.

Waiting for the pRBCCsn to arrive, doctors called the patients to reschedule their appointments. Patients were also called as soon as pRBCCsn were received to avoid useless and costly trips to the hospital, resulting in a prolongation of the release time with a median of 2 days. Meanwhile, staff made calls multiple times a day to the national center of blood transfusion to insist on the urgent need for blood.

One of the good practice measures also adopted by the blood bank was reassigning 214 pRBCCsn to other patients who were in urgent need of blood. This practice was conducted in collaboration with the hematology department doctors. This strong framework of accepted procedures with clinicians is in fact a sine qua none condition to the success of local hospital initiatives for PBM. Despite those initiatives, national blood shortage negatively impacted patient management. Indeed, on April 10, the national center of blood transfusion published a call for blood donations stating that the blood supply reached very low values. One of the factors explaining this decline in blood supply was the general lockdown. National efforts were, thus, displayed to encourage blood donation. For example, special circulation authorizations were sent by email to prospect blood donors.

In the blood centers of Zhejiang province China, to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission, which discouraged donors, social sterilization and social distancing were strictly respected. To reduce blood demand, elective surgeries were postponed, and restrictive transfusion strategies were adopted [12]. Meanwhile, in King Abdullah Hospital, Saudi Arabia, mobile blood drives at donors’ homes were organized after coordinating with the donors through their private social media [13].

Knowing that the current COVID-19 pandemic is probably going to be a lengthy battle, preparing a plan to manage blood supply is urgent and mandatory. The role of transfusion specialist seems more essential than ever. That is why, in collaboration with the Tunisian Ministry of Health, many transfusion specialists, mainly blood bank directors and physicians in blood banks and deposits, are reviewing the national blood transfusion strategy to avoid future blood shortage disasters.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Presented during the 1st EFLM/AFCB Conference “Laboratory Medicine for Mobile Societies” and the XXXIVth National Days of Clinical Biology, held virtually from February 18th to February 20th 2021.

References

- 1.Pourhosseini S.S., Ardalan A., Mehrolhassani M.H. Key Aspects of Providing Healthcare Services in Disaster Response Stage. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(1):111–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease.(COVID-19) outbreak [Online]. [Cited 2021 Jan 31]; Available from https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19).

- 3.Barrett C.L. Primary healthcare practitioners and patient blood management in Africa in the time of coronavirus disease 2019: Safeguarding the blood supply. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2021;12(1) doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouka E. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the adequacy of blood supply: Specialists in transfusion medicine need to establish models of preparedness. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102960. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association of Blood Banks. Disaster Response [online]. [Cited 2021 Jan 31] Available from: https://www.aabb.org/about-aabb/organization/disaster-response.

- 6.Garraud O. COVID-19: Is a paradigm change to be expected in health care and transfusion medicine? Transfus Clin Biol. 2020;27(2):59–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velázquez-Kennedy K., Luna A., Sánchez-Tornero A., Jiménez-Chillón C., Jiménez-Martín A., Vallés Carboneras A., et al. Transfusion support in COVID-19 patients: Impact on hospital blood component supply during the outbreak. Transfusion. 2020 doi: 10.1111/trf.16171. [trf.16171] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Riyami A.Z., Abdella Y.E., Badawi M.A., Panchatcharam S.M., Ghaleb Y., Maghsudlu M., et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on blood supplies and transfusion services in Eastern Mediterranean Region. Transfus Clin Biol. 2021;28(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettman T.L., Armstrong R., Doyle J., Burford B., Anderson L.M., Hillgrove T., et al. Strengthening evaluation to capture the breadth of public health practice: ideal vs. real. J Public Health. 2012;34(1):151–155. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowman Z., Fei N., Ahn J., Wen S., Cumpston A., Shah N., et al. Single versus double-unit transfusion: safety and efficacy for patients with hematologic malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102(5):383–388. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman MT. Patient blood management in hematology and oncology [online]. [Cited 2021 Mai 19]. Available from: https://www.aabb.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/resources/pbm-in-hematology-and-oncology.pdf?sfvrsn=21725df9_0.

- 12.Wang Y., Han W., Pan L., Wang C., Liu Y., Hu W., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on blood centres in Zhejiang province China. Vox Sang. 2020;115(6):502–506. doi: 10.1111/vox.12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yahia A.I.O. Management of blood supply and demand during the COVID-19 pandemic in King Abdullah Hospital, Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59(5) doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102836. [102836] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]