Abstract

The events that lead to choroidal neovascularization in eyes with age-related macular degeneration are poorly understood. One possibility that has been explored in a number of studies is that macrophages can promote neovascular changes. In this manuscript we summarize the evidence for inflammation in general and macrophages in particular in pathologic neovascularization, and discuss how the diverse functions of these cells may promote or inhibit macular disease. We also discuss some of the conflicting findings regarding the role of macrophages in experimental choroidal neovascularization in mouse models, and suggest areas for future research.

Introductory comments:

During the American Civil War, it is popularly believed that the United States troops (or “the Union”) wore dark blue uniforms while the secessionist Confederate States troops wore gray. This was generally the case. However, since both armies included assorted militias from the member states, numerous exceptions existed in which Southern troops wore blue and Northern units wore gray. Added to the smoke, noise and confusion of battle, the inability of the respective commanders to unambiguously determine the affiliations and loyalties of approaching troops could lead to disastrous consequences. One example of the chaos resulting from this lack of certainty about the intentions of uniformed participants was seen in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri. The Union army, holding territory soon to be named Bloody Hill, mistakenly identified approaching blue-coated Confederate troops as friendly Union reinforcements, allowing them to march within a few yards before the Confederates opened fire and the Union troops were routed.

In the case of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD), there is ambiguity surrounding the role of macrophages in the disease process, with conflicting evidence regarding whether they are helpful or harmful. An improved understanding of whether these cells promote macular disease or are beneficial will be essential for scientists and clinicians interested in understanding and treating AMD. In this review we will discuss evidence that macrophages participate in exudative and non-exudative AMD, some of the relevant clinical studies, data from post-mortem human tissue, and interventional experiments using animal models. We will also suggest approaches to further clarify the roles of macrophages in AMD.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD):

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in the Western world (1–3). In the United States alone, nearly two million individuals are afflicted with severe, end stage AMD, and are legally blind. Seven million more have early stage AMD, or age-related maculopathy (ARM), and are at high risk for developing advanced AMD (4). As the population ages, the negative impact of AMD on society will increase (4, 5).

Defining "macrophages":

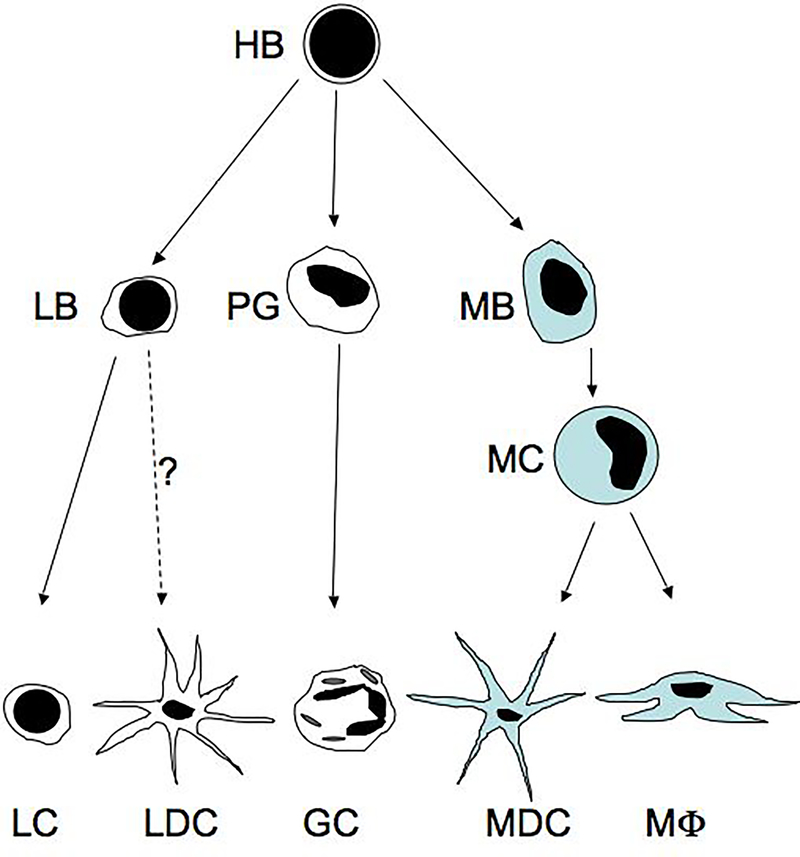

For the purposes of this review, “macrophage” will be defined as hematopoietic cells that are derived from hemocytoblasts in bone marrow and that travel through the systemic circulation as monocytes (Figure 1). These cells characteristically express the cluster differentiation (CD) antigens that include CD14, CD11b, CD18 and CD68, and perform roles in phagocytosis, scavenging debris, antigen presentation, and secretion of cytokines. Numerous classes of macrophages are recognized, with diversity that includes multinucleated osteoclasts in bone and alveolar macrophages that reside at the lung-air interface. In the eye, circulating monocytic cells exit the vasculature through endothelial cells in the choroid or retina during normal development, aging and disease. In the choroid, the distribution of resident cells is best appreciated by choroidal whole mounts which show these cells to be fairly evenly spaced in dense networks (6). Choroidal cells of monocytic origin include circulating monocytes, resident macrophages, and dendritic cells. Upon exiting the vasculature, monocytes can differentiate into either macrophages or dendritic cells depending on microenvironmental cues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simplified model of leukocyte differentiation.

Bone marrow hemocytoblasts (HB), which may already be specialized in some cases, give rise to progenitor cells including lymphoblasts (LB), progranulocytes (PG), and monoblasts (MB). These cells then differentiate into lymphocytes (LC) or arguably lymphoid dendritic cells (LDC), different classes of granulocytes (GC), and monocytes (MC), respectively. Circulating monocytes leave the vasculature and differentiate into myeloid dendritic cells (MDC) and macrophages (MΦ), based on microenvironmental cues.

Association of inflammation and macrophages with choroidal neovascularization—Clinical and Genetic Studies:

Several clinical studies have been published that provide information about the possible role of inflammatory cells in choroidal neovascularization (CNV). In an early phenotype association study, Blumenkranz and colleagues identified elevated white blood cell counts as one of the few systemic indicators correlating with neovascular AMD (7). Similarly, a recent report on the Blue Mountain cohort in Australia also found increased white blood cell counts associated with early AMD, drusen and possibly with geographic atrophy, although there was not a significant increase in patients with choroidal neovascularization (8). Moreover, there is evidence of increased activation of circulating monocytes in patients with CNV (9). In addition to studies of circulating cells, biochemical studies from CNV patients also have shown levels of C-reactive protein and the cytokine interleukin-6 to be elevated in the serum in association with progression to CNV (10, 11). These experiments are intriguing as they point to systemic inflammatory factors, in addition to local ocular events, in the pathogenesis of AMD.

Anti-inflammatory treatments that affect macrophages may also be beneficial to AMD patients. In several studies of CNV patients, intravitreal injection of the anti-inflammatory steroid triamcinolone has been shown to be beneficial (12), either alone or in conjunction with additional treatment modalities (e.g., photodynamic therapy) (13). Administration of triamcinolone via a synthetic implant was also found to be protective against experimental CNV in a rat model (14). It should be noted, however, that triamcinolone likely affects multiple intercellular pathways in addition to inflammation, and the modulation of these pathways (such as apoptosis) may be as important or more important than the impact of this steroid on inflammation.

In the last few years, there has been tremendous progress in identifying genetic risk factors for AMD (recently reviewed (15–17)). Notably, several AMD associated risk alleles are located in genes whose products participate in inflammation, either directly (CX3CR1, MHC alleles) (18, 19) or indirectly (complement factor H, complement factor 2, complement factor B) (20–23). Although the biochemical details of how each of these alleles affects protein function remain to be determined, these genetic associations contribute to the notion that inflammation has a role in the pathogenesis of AMD.

Evidence of inflammation and macrophage participation in CNV— Histopathologic Studies:

There is indirect evidence that macrophages may participate in both early AMD and in advanced, exudative AMD. Macular drusen represent important indicators of early AMD, and it is widely appreciated that the number, size, and confluency of drusen in the macula is a major risk factor for atrophic and/or neovascular changes in the aging macula (e.g., (24–26)). Studies examining the composition of drusen revealed that they are largely comprised of numerous mediators of inflammation (27–29).

Macrophages have been shown to be localized to degraded areas of Bruch’s membrane in eyes with advanced AMD (30, 31) and are found in increased numbers within the choroid of eyes with AMD (32). Human choroidal neovascular membranes have been shown to contain leukocytes of the macrophage lineage (33). These cells are concentrated near pathologic vascularization as found by transmission electron microscopy (34) and CD68 immunohistochemistry (35). Moreover, macrophages within CNVM have been shown to express pro-angiogenic cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), indicating that macrophages might directly promote aberrant endothelial cell growth in CNV (36).

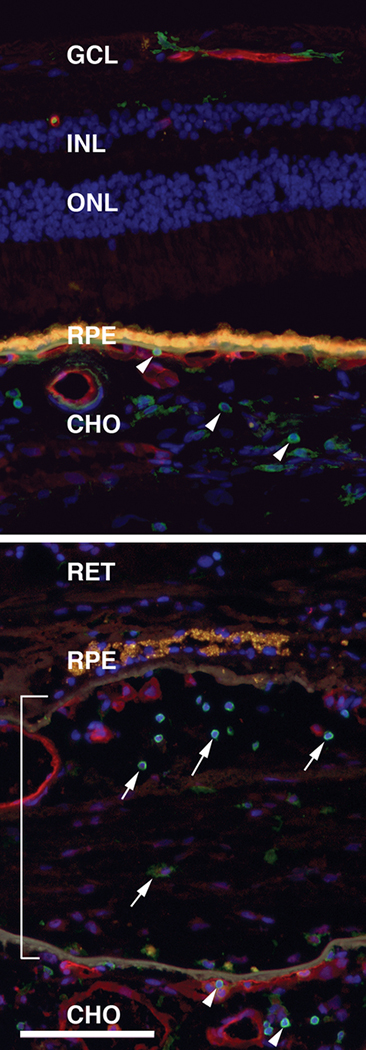

Figure 2 depicts immunohistochemical labeling of CD45 positive leukocytes in an unaffected eye (top) and in an eye with a choroidal neovascular membrane (bottom).

Figure 2. Leukocyte localization in human eyes.

Leukocytes localized in the normal human choroid of an 84 year old donor (top panel) and in an eye from an 80 year old donor with choroidal neovascularization (lower panel). Sections were labeled with antibodies directed against leukocyte common antigen, a protein expressed in all classes of leukocytes (CD45; green labeling) and with the lectin Ulex europeaus agglutinin-I to visualize the vasculature (red labeling)(85). Nuclei are counterstained blue with DAPI. Yellow-orange fluorescence is due to RPE lipofuscin. Choroidal leukocytes are indicated by arrowheads, leukocytes within the CNVM are indicated by arrows, and the CNVM is indicated by the bracket. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; CHO, choroid. Scale bar = 100μm.

How might macrophages promote macular degeneration?

One of the more surprising findings made in studies of drusen composition is the presence of MHC class II antigens in these deposits (19, 27, 37). These transmembrane proteins (that are typically expressed by antigen-presenting cells) are located in core like structures and are often dispersed throughout drusen (19, 38). Although the possibility that these cells are removing drusen cannot be ruled out (see below), the dispersion of these antigens throughout the deposits may suggest that cells of monocytic origin are involved in the pathogenesis of drusen formation (37). Second, in order for subretinal neovascularization to occur, it is necessary for endothelial cells to migrate through defects in Bruch’s membrane. In the experimental CNV mouse model (discussed below), these defects are created by laser injury; in AMD, the precipitating event is not known. The dissolution of Bruch’s membrane, which is largely comprised of elastin and collagen, likely relies on matrix metalloproteinases. Macrophages and neutrophils play significant roles in extracellular matrix turnover and express a number of matrix metalloproteinases that could reasonably lead to Bruch’s membrane breakdown. Third, leukocyte transmigration through the endothelium can in itself promote endothelial cell injury and death in other tissues (39). Such a mechanism could place the macular, as compared to peripheral, choriocapillaris at greater risk for injury since the macular choriocapillaris tends to exhibit higher expression of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (40) and might therefore subject the macular endothelium to increased monocyte transmigration. Hypoperfusion of the choriocapillaris resulting from transmigration-induced endothelial injury is a plausible mechanism for exudative conversion in AMD, especially in eyes with high risk of developing CNV in which perfusion has been shown to be decreased (41). Finally, macrophages can secrete growth factors, cytokines and reactive oxygen species (42) that may negatively affect the choriocapillaris and RPE.

It is further worth considering that two areas of great recent interest in AMD—the complement system and anti-VEGF therapy—are likely to modulate the function of circulating leukocytes in AMD. For example, anaphylotoxins generated during the formation of complement complexes have a number of bioactive effects on leukocytes, including increased migration and synthesis of proinflammatory mediators(43). It is also interesting, in light of the success of anti-VEGF therapies in the management of neovascular AMD, that VEGF itself increases expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules and elevates recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils under some conditions, in addition to its well-appreciated direct effects on vascular growth(44, 45).

How might macrophages protect against macular degeneration?

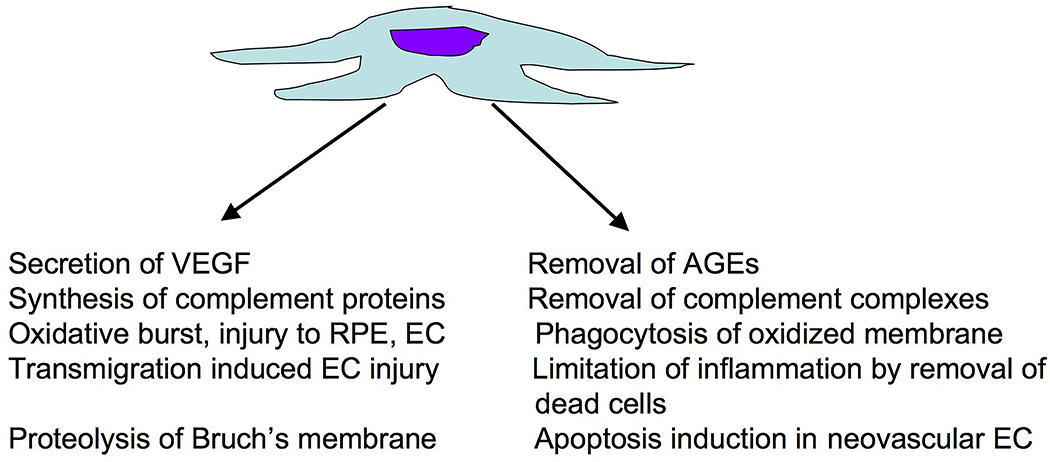

In addition to drusen, which are clinically apparent, the presence of membranous debris and basal linear deposit in Bruch’s membrane represent morphological signs of AMD (46–50). It has been suggested that macrophages play a role in removal of drusen and other waste products, perhaps preventing the severe end stage pathology that can occur after the accumulation of these deposits (51, 52). Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) is a chemokine that directs monocyte recruitment into inflamed tissues (53). Mice deficient for this protein, especially when also deficient for the chemokine receptor CX3CR1, were reported to exhibit drusen-like deposits, suggesting that impaired macrophage recruitment results in reduced clearance of debris from Bruch’s membrane(54)-(55). Aging human Bruch’s membrane accumulates advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) (56, 57), which can induce increased secretion of VEGF in cultured RPE cells (58). Since macrophages can endocytose and remove AGEs (59, 60), a failure to recruit macrophages could thus lead to increased AGE exposure to the RPE and choriocapillaris, with concomitant injury and/or increased levels of proangiogenic cytokines. The removal of apoptotic cell debris by macrophages can also limit inflammation through inhibiting the production of inflammatory cytokines (61). These proposed functions are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Potential harmful (left) and beneficial (right) roles of macrophages in the progression of neovascular AMD.

Functional studies of macrophages in CNV and their limitations:

As discussed in the previous sections, there is compelling histological evidence for a spatial association between immune cells (monocytes or macrophages) and human choroidal neovascular membranes. Of course, the presence of macrophages and other immune cells at the site of a lesion does not in itself show whether these cells are responsible for inducing the lesion or are somehow mitigating its severity. Studies that rely on human donor tissue, while the most reliable in terms of observing actual human pathology, are limited in that only a single “snapshot” of the disease process is surveyed (although it is hoped that sufficient numbers of static images from different stages of disease can produce a more dynamic and complete understanding). Animal models of CNV, in which genetic and environmental parameters can be altered, play a complementary role to human tissue based studies and can shed further light on the role of macrophages in CNV.

The most commonly employed animal model of choroidal neovascularization relies upon thermal laser-induced breaks in Bruch’s membrane, which allow subsequent subretinal neovascularization at the site of injury. The use of thermal laser to induce choroidal neovascularization was initially described in primates (62) and subsequently in rodents (63). This type of experiment has been of particular value in mice, in which the effects of different interventions and genetic backgrounds on CNV can be readily controlled. Although the events leading to human CNV are clearly different from those in laser induced trauma, the subsequent steps of angiogenesis that occur in human CNV are likely to be reflected in the laser injury model.

The use of thermal laser to induce CNV has been used in a number of elegant studies in which leukocyte function was inhibited in mice. Two studies published in 2003 evaluated the effects of monocyte depletion on laser induced choroidal neovascularization. Espinosa-Heidman et al. pretreated mice with clodronate liposomes prior to inducing CNV (64). Clodronate promotes apoptosis of monocytes and macrophages that phagocytose the liposomes, leading to depletion of both circulating and resident cell populations (65). CNV severity—as assessed by lesion size—was significantly decreased in mice that were injected with clodronate liposomes, compared with controls, following CNV induction. In a simultaneously published report, Sakurai et al. also utilized the clodronate liposome method (66). In these studies, the volume of CNVMs was significantly reduced in animals treated with clodronate. Moreover, morphological studies were interpreted as showing macrophages (CD45+, F4/80+ cells) preceding endothelial cells into areas of developing CNV. Significantly, the levels of vascular endothelial growth factor were decreased in clodronate-treated animals, suggesting that macrophages are contributing to VEGF synthesis, as suggested previously in human CNVMs (36).

Mice that are genetically deficient in macrophage recruitment or signaling show similarly decreased severity of CNV as mice that are pharmacologically depleted of macrophages. Knockout mice lacking Ccr2, the gene encoding the receptor for monocyte chemotactic protein-1, have severely impaired ability to recruit monocytes to areas of inflammation. When Bruch’s membrane of these animals is ruptured with thermal laser, they were found to produce much smaller neovascular membranes than wild type mice (67). Mice deficient for the endothelial surface molecule intercellular adhesion molecule-1 or one of its binding partners, CD18, also demonstrated impaired neovascularization following laser treatment (68). Thus, both pharmacologic and genetic impairment of monocytes appears protective against CNV in several studies.

In addition to monocytes/macrophages, the potential role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes has also been explored, with evidence for a modest contribution of these cells to experimental CNV (69, 70) although the significance of the observed effects on CNV size has differed between studies.

Taken together, there is considerable evidence for macrophage participation in the pathogenesis of CNV in the mouse model and, perhaps, human eyes with AMD.

The proposal that these cells exacerbate CNV has recently been challenged, however, by a multifaceted study in which Apte et al. provided evidence that macrophages inhibit the development of experimental CNV (71). These investigators also employed the laser-induced model of CNV, in this case with mice deficient for interleukin-10 (IL-10), in order to determine the effects of macrophage suppression on subsequent CNVM formation. IL-10 is a cytokine that is generally considered anti-inflammatory with a role in inhibiting the function of macrophages. One would hypothesize that, based on the proposed role of macrophages in promoting CNV, the severity of CNV would increase in the absence of IL-10. The opposite result was actually observed—with IL-10 knocked out, or its effective concentrations reduced by the addition of exogenous anti-IL-10 antibody, mice developed less severe CNV. This effect was correlated with the extent of macrophage (or CD11b and F4/80 positive cells) migration into the lesion site. To determine if the converse was true, transgenic mice over-expressing IL-10 were generated, and these animals exhibited increased susceptibility to CNV in comparison to the wild type littermates. In addition, Apte and colleagues found that monocytic cells injected into the vitreous, although not reflective of AMD pathophysiology, also prevented CNVMs from developing as significantly as in eyes injected with other cell types, through a mechanism likely to involve CD95 signaling. Overall, this study provided significant evidence from both positive and negative approaches that macrophages may mitigate the severity of choroidal neovascularization in the experimental injury model, challenging several previous studies.

In attempting to reconcile these disparate findings, and better define the role of macrophages in CNV, a few considerations are outlined below:

What are the effects of macrophage depletion in the absence of laser?

Each of these studies utilized mice with genetic or pharmacologic interventions to affect macrophage number or function, followed by treatment with thermal laser and evaluation of CNV severity. Surprisingly, the possible effects of these treatments on non-lasered eyes have not been well established. It is possible, as suggested, that clodronate liposome treatment or other modalities may lead to death or injury of the endothelium, in addition to depletion of circulating monocytes (71). This is an important consideration; clearly a modality that kills or inhibits the proliferation of the choroidal endothelium would be expected to reduce the severity of CNVMs, and its simultaneous effects on macrophages would be interesting but irrelevant. Whereas animals exposed to clodronate liposomes in other studies are viable (65), and this delivery does not appear to cause widespread vascular dropout and tissue necrosis, it is feasible that the RPE and choriocapillaris are especially sensitive to this drug. This question might be addressed by clodronate treatment, followed by reconstitution of monocytes into the circulation; if untreated monocytes are unable to restore a severe CNV phenotype, this result would call into question whether clodronate’s most important biological effect in this experiment is through monocyte depletion.

Similarly, with respect to IL-10, it will be important to establish whether this cytokine affects the RPE-Bruch’s membrane-choriocapillaris complex in vivo. Whereas Apte and colleagues show that overexpression of IL-10 does not have a severe affect on the overall structure of the retina, detailed, high resolution quantitative studies will be necessary to explore whether there are subtle changes at the level of the choriocapillaris and/or Bruch’s membrane in IL-10 deficient mice, IL-10 transgenic mice, and clodronate-liposome treated mice. Careful immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies of the choroidal vasculature, Bruch’s membrane and RPE in animals with each of these treatment regimens and genotypes, such as those used previously to evaluate the effects of cigarette smoke on the RPE-choroid complex (72), are especially warranted.

Although IL-10 is generally considered an anti-inflammatory cytokine, it appears to have pleiotrophic effects, with either immunosuppressive or immunostimulatory functions, depending on its microenvironment, the type of stimulus, and the model system employed (73). One effect observed in vitro is endothelial cell activation and upregulation of the endothelial cell adhesion molecule E-selectin (74), and some human patients receiving IL-10 showed an increase in plasma levels of some pro-inflammatory cytokines (75). There may also be relevant extracellular matrix changes associated with loss of IL-10; this cytokine downregulates collagen I synthesis in vitro (76) and may therefore affect the kinetics of scar formation, as noted in a recent editorial (77). Moreover, collagen I is a component of Bruch’s membrane (78) and changes in the ECM composition of Bruch’s membrane may lead to altered propensity to form neovascular membranes. Therefore, while at face value each of these studies approaches the same question with regard to macrophage depletion, the biological impact of IL-10 administration, IL-10 deficiency, and clodronate treatment may be complex.

What are the effects of macrophage depletion in laser-independent models of CNV?

The laser induced CNV model is highly tractable, with a predictable time course and high degree of control by the investigator; however, the injury created in this model (in which a normal, healthy Bruch’s membrane is suddenly disrupted) differs substantially from the pathology in human CNV, which takes years to develop. Transgenic mice overexpressing VEGF exhibit intrachoroidal neovascularization, in a similar pattern to that described in human diabetic choroid (79), but have not been consistently found to develop subretinal neovascularization (80). Recently, alternative mouse models of subRPE deposits and spontaneous CNV have been described. Mice transgenic for the human apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele, when placed on a high fat diet, developed subRPE lesions as well as choroidal (and retinal) neovascularization. In addition, mice deficient for superoxide dismutase-1 (81) were also found to have focal drusen-like deposits, although these were less than the height of an RPE cell, and diffuse basal deposits. Spontaneous CNV was observed in these animals as well. As noted above, mice deficient for the genes encoding both MCP-1 and CX3CR1 also develop subRPE deposits and also develop spontaneous CNV (55). These models, and those that will be developed from genetic progress in understanding AMD, may offer new possibilities to evaluate the role of macrophages in CNV. Specifically, the effects of modifying the number and function of different classes of macrophages may be explored in what may be more medically relevant models of neovascularization.

Do different macrophage classes have different effects on CNV?

There has been considerable progress in identifying and characterizing phenotypically different classes of monocytes and macrophages in human (82) and mouse (83), (recently reviewed (84)). These distinct classes of monocytes appear to have different functional properties and varying propensities to differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells in response to different microenvironmental conditions. The murine studies to date have described macrophage populations in experimental CNVMs as F4/80+, CD11b+ and/or CD45+ cells. These markers appear to label all classes of mouse monocytes and macrophages, and do not discriminate between different subsets. Hence, it is possible that the increased transmigration of macrophages in IL-10 deficient mice may represent a different and more benign population of cells than those seen in other genotypes and associated with more severe CNV. Further studies using additional markers, such as CD11c and CD62L (84) may further refine whether the “macrophages” in each of these studies are truly the same cells.

Conclusions:

In summary, despite several excellent studies to date, there is a lack of consensus on whether macrophages act to reduce CNV, exacerbate CNV, have mixed effects depending on genotype and environmental milieu, or are incidental bystanders in the process. Subtle, but important, differences in the experimental approaches taken by different groups make comparison of these experiments difficult. Understanding the role of circulating inflammatory cells in the development and progression of AMD is of clear importance regarding additional therapeutic approaches for this devastating disease. Future studies will require determining the effects of clodronate liposomes and of IL-10, CD18 and ICAM-1 deficiencies alone on the biology of the RPE-Bruch’s membrane-choriocapillaris complex. If possible, separating the anti-inflammatory from the anti-angiogenic activities of IL-10 will be helpful, especially if these are found to be mediated by different receptors. In addition, it will be important to demonstrate that a severe CNV phenotype can be “rescued” in mice deficient for CD18 or treated with clodronate liposomes by transfusion of healthy monocytes (of various subpopulations) into treated animals.

Based on the preponderance of data, we propose that it is most likely that macrophages contribute to the transition to neovascular AMD. It is especially compelling that observations from human eyes in which macrophages have consistently been observed at the scene of the crime (within CNVMs) and holding a smoking revolver (or at least expressing VEGF). This suggests that inhibition of their activity would be helpful for patients.

However, there are alternative explanations for the findings in human eyes, and studies in mouse models suggest that the picture may be complicated. A more thorough understanding of the role of leukocytes in AMD will be of significant benefit. One can easily envision a situation in which some classes of leukocytes promote CNV. In this case, it would be beneficial to interfere with their migration, signaling, VEGF secretion and other functions in an eye with high risk of developing CNVM (for example, in an eye with soft macular drusen, a high risk genotype and a CNVM in the contralateral eye). However, if some classes of leukocytes in the better eye are slowing the course of CNV, then inhibiting these cells would be counterproductive and harmful. Further refining the harmful and potential helpful roles of these cells in choroidal neovascularization will be beneficial in guiding the development of new therapies and in applying existing therapies that act on leukocytes and inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

Supported in part by National Eye Institute grant EY-017451 and the Macula Vision Research Foundation. The authors would like to thank Drs. John E. Mullins, Michael G. Anderson, John H. Fingert, Markus H. Kuehn and Stephen R. Russell for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Klein R, Klein B, Cruickshanks K. The prevalence of age-related maculopathy by geographic region and ethnicity. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:371–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buch H, Vinding T, Nielsen N. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment according to World Health Organization and United States criteria in an aged, urban Scandinavian population: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith W, Assink J, Klein R, Mitchell P, Klaver C, Klein B, et al. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: Pooled findings from three continents. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman D, O'Colmain B, Munoz B, Tomany S, McCarty C, deJong P, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.VanNewkirk M, Nanjan M, Wang J, Mitchell P, Taylor H, McCarty C. The prevalence of age-related maculopathy: the visual impairment project. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMenamin P. The distribution of immune cells in the uveal tract of the normal eye. Eye. 1997;11:183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenkranz M, Russell S, Robey M, Kott-Blumenkranz R, Penneys N. Risk factors in age-related maculopathy complicated by choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar A, Mitchell P, Rochtchina E, Tan J, Wang JJ. Association between Circulating White Blood Cell Count and Long-Term Incidence of Age-related Macular Degeneration. Am J Epidemiol. 2006. November 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cousins S, Espinosa-Heidmann D, Csaky K. Monocyte activation in patients with age-related macular degeneration: a biomarker of risk for choroidal neovascularization? Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1013–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seddon J, Gensler G, Milton R, Klein M, Rifai N. Association between Creactive protein and age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 2004;291:704–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seddon JM, George S, Rosner B, Rifai N. Progression of age-related macular degeneration: prospective assessment of C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and other cardiovascular biomarkers. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005. June;123(6):774–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranson NT, Danis RP, Ciulla TA, Pratt L. Intravitreal triamcinolone in subfoveal recurrence of choroidal neovascularisation after laser treatment in macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002. May;86(5):527–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser PK. Verteporfin therapy in combination with triamcinolone: published studies investigating a potential synergistic effect. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005. May;21(5):705–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciulla TA, Criswell MH, Danis RP, Fronheiser M, Yuan P, Cox TA, et al. Choroidal neovascular membrane inhibition in a laser treated rat model with intraocular sustained release triamcinolone acetonide microimplants. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003. August;87(8):1032–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddad S, Chen CA, Santangelo SL, Seddon JM. The genetics of age-related macular degeneration: a review of progress to date. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006. Jul-Aug;51(4):316–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullins RF. Genetic insights into the pathobiology of age-related macular degeneration. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholl H, Fleckenstein M, Charbel Issa P, Keilhauer C, Holz F, Weber B. An update on the genetics of age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 2007;13:196–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuo J, Smith BC, Bojanowski CM, Meleth AD, Gery I, Csaky KG, et al. The involvement of sequence variation and expression of CX3CR1 in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Faseb J. 2004. August;18(11):1297–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goverdhan S, Mullins R, Howell W, Osmond C, Hodgkins P, Self J, et al. Association of HLA Class I and Class II Polymorphisms with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005 May 2005;46(5):1726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein R, Zeiss C, Chew E, Tsai J, Sackler R, Haynes C, et al. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards A, Ritter R, Abel K, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer L. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haines J, Hauser M, Schmidt S, Scott W, Olson L, Gallins P, et al. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:419–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold B, Merriam JE, Zernant J, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Gehrs K, et al. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006. April;38(4):458–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bressler S, Maguire G, Bressler N, Fine S. Relationship of drusen and abnormalities of the retinal pigment epithelium to the prognosis of neovascular macular degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1990;108:1442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauleikhoff D, Barondes M, Minassian D, Chisholm I, Bird A. Drusen as risk factors in age-related macular disease. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1990;109:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risk factors for choroidal neovascularization in the second eye of patients with juxtafoveal or subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1997;115(6):741–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullins R, Anderson D, Russell S, Hageman G. Ocular drusen contain proteins common to extracellular deposits associated with atherosclerosis, elastosis, amyloidosis, and dense deposit disease. FASEB Journal. 2000;14:835–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson L, Ozaki S, Staples M, Erickson P, Anderson D. A potential role for immune complex pathogenesis in drusen formation. Exp Eye Res. 2000;70:441–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hageman G, Anderson D, Johnson L, Hancox L, Taiber A, Hardisty L, et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7227–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penfold P, Killingsworth M, Sarks S. An ultrastructural study of the role of leucocytes and fibroblasts in the breakdown of Bruch's membrane. Australian Journal of Ophthalmology. 1984;12:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penfold P, Provis J, Billson F. Age-related macular degeneration: ultrastructural studies of the relationship of leukocytes to angiogenesis. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1987;225:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penfold P, Killingsworth M, Sarks S. Senile macular degeneration: the involvement of immunocompetent cells. Graefe's Archives for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1985;223:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez P, Grossniklaus H, Lambert H, Aaberg T, Capone A, Sternberg P, et al. Pathologic features of surgically excised subretinal neovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1991;112:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grossniklaus H, Green W. Histopathologic and ultrastructural findings of surgically excised choroidal neovascularization. Submacular Surgery Trials Research Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:745–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossniklaus H, Cingle K, Yoon Y, Ketkar N, ĽHernault N, Brown S. Correlation of histologic 2-dimensional reconstruction and confocal scanning laser microscopic imaging of choroidal neovascularization in eyes with age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:625–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossniklaus HE, Ling JX, Wallace TM, Dithmar S, Lawson DH, Cohen C, et al. Macrophage and retinal pigment epithelium expression of angiogenic cytokines in choroidal neovascularization. Mol Vis. 2002. April 21;8:119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hageman G, Luthert P, Chong N, Johnson L, Anderson D, Mullins R. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch's membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:705–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hageman GS, Mullins RF. Association of major histocompatibility class II antigens with core subdomains present within human ocular drusen. In: Zierhut M, Rammensee H, Streilein WJ, editors. Antigen-presenting Cells and the Eye. London: Taylor & Francis Medical Books; 2007. p. 209–16. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radi Z, Kehrli M, Ackermann M. Cell adhesion molecules, leukocyte trafficking, and strategies to reduce leukocyte infiltration. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:516–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mullins R, Skeie J, Malone E, Kuehn M. Macular and peripheral distribution of ICAM-1 in the human choriocapillaris and retina. Mol Vis. 2006;12:224–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grunwald J, Metelitsina T, Dupont J, Ying G, Maguire M. Reduced foveolar choroidal blood flow in eyes with increasing AMD severity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1033–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szekanecz Z, Koch A. Macrophages and their products in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;19:289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gasque P. Complement: a unique innate immune sensor for danger signals. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:1089–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinders M, Sho M, Izawa A, Wang P, Mukhopadhyay D, Koss K, et al. Proinflammatory functions of vascular endothelial growth factor in alloimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1655–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zittermann S, Issekutz A. Endothelial growth factors VEGF and bFGF differentially enhance monocyte and neutrophil recruitment to inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarks S. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinicopathological study. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1976;60(5):324–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green W, Enger C. Age-related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1519–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curcio C, Millican C. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1999;117:329–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curcio C, Presley J, Malek G, Medeiros N, Avery D, Kruth H. Esterified and unesterified cholesterol in drusen and basal deposits of eyes with age-related maculopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:731–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarks S, Cherepanoff S, Killingsworth M, Sarks J. Relationship of Basal laminar deposit and membranous debris to the clinical presentation of early age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:968–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duvall J, Tso M. Cellular mechanisms of resolution of drusen after laser coagulation: an experimental study. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1985;103:694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forrester J. Macrophages eyed in macular degeneration. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:1350–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Charo I, Taubman M. Chemokines in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Circ Res. 2004;95:858–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ambati J, Anand A, Fernandez S, Sakurai E, Lynn B, Kuziel W, et al. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(11):1390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuo J, Bojanowski C, Zhou M, Shen D, Ross R, Rosenberg K, et al. Murine ccl2/cx3cr1 deficiency results in retinal lesions mimicking human age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3827–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Handa J, Verzijl N, Matsunaga H, Aotaki-Keen A, Lutty G, te Koppele J, et al. Increase in the advanced glycation end product pentosidine in Bruch's membrane with age. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1999;40(3):775–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishibashi T, Murata T, Hangai M, Nagai R, Horiuchi S, Lopez P, et al. Advanced glycation end products in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1629–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma W, Lee S, Guo J, Qu W, Hudson B, Schmidt A, et al. RAGE ligand upregulation of VEGF secretion in ARPE-19 cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.el Khoury J, Thomas C, Loike J, Hickman S, Cao L, Silverstein S. Macrophages adhere to glucose-modified basement membrane collagen IV via their scavenger receptors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohgami N, Nagai R, Ikemoto M, Arai H, Kuniyasu A, Horiuchi S, et al. CD36, a member of the class b scavenger receptor family, as a receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fadok V, Bratton D, Konowal A, Freed P, Westcott J, Henson P. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin INvest. 1998;101:890–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryan S. Subretinal neovascularization after argon laser photocoagulation. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1980. none given;215(1):29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tobe T, Okamoto N, Vinores M, Derevjanik N, Vinores S, Zack D, et al. Evolution of neovascularization in mice with overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor in photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:180–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Espinosa-Heidman D, Suner I, Hernandez E, Monroy D, Csaky K, Cousins S. Macrophage depletion diminishes lesion size and severity in experimental choroidal neovascularization. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(8):3586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Biewenga J, van der Ende M, Krist L, Borst A, Ghufron M, van Rooijen N. Macrophage depletion in the rat after intraperitoneal administration of liposome-encapsulated clodronate: depletion kinetics and accelerated repopulation of peritoneal and omental macrophages by administration of Freund's adjuvant. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakurai E, Anand A, Ambati B, van Rooijen N, Ambati J. Macrophage depeletion inhibits experimental chorodial neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(8):3578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsutsumi C, Sonoda KH, Egashira K, Qiao H, Hisatomi T, Nakao S, et al. The critical role of ocular-infiltrating macrophages in the development of choroidal neovascularization. J Leukoc Biol. 2003. July;74(1):25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakurai E, Taguchi H, Anand A, Ambati B, Gragoudas E, Miller J, et al. Targeted disruption of the CD18 or ICAM-1 gene inhibits choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2743–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsutsumi-Miyahara C, Sonoda K, Egashira K, Ishibashi M, Qiao H, Oshima T, et al. The relative contributions of each subset of ocular infiltrated cells in experimental choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004 September 2004;88(9):1217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou J, Pham L, Zhang N, He S, Gamulescu M, Spee C, et al. Neutrophils promote experimental choroidal neovascularization. Mol Vis. 2005;11:414–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Apte RS, Richter J, Herndon J, Ferguson TA. Macrophages Inhibit Neovascularization in a Murine Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. PLoS Med. 2006. August 15;3(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Suner IJ, Catanuto P, Hernandez EP, Marin-Castano ME, Cousins SW. Cigarette smoke-related oxidants and the development of sub-RPE deposits in an experimental animal model of dry AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006. February;47(2):729–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mocellin S, Marincola F, Rossi C, Nitti D, Lise M. The multifaceted relationship between IL-10 and adaptive immunity: putting together the pieces of a puzzle. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vora M, Romero L, Karasek M. Interleukin-10 induces E-selectin on small and large blood vessel endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li B, Nayini J, Sivaraman S, Song S, Larson A, Toofanfard M, et al. In vivo effects of IL-4, IL-10, and amifostine on cytokine production in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;41:1661–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wangoo A, Laban C, Cook H, Glenville B, Shaw R. Interleukin-10- and corticosteroid-induced reduction in type I procollagen in a human ex vivo scar culture. Int J Exp Pathol. 1997;78:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lightman S, Calder V. Is IL-10 a Good Target to Inhibit Choroidal Neovascularisation in Age-Related Macular Disease? PLoS Med. 2006;3(8):Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Newsome D, Hewitt A, Huh W, Robey P, Hassell J. Detection of specific extracellular matrix molecules in drusen, Bruch's membrane, and ciliary body. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1987;104:373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fukushima I, McLeod D, Lutty G. Intrachoroidal microvascular abnormality: a previously unrecognized form of choroidal neovascularization. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1997;124(4):473–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schwesinger C, Yee C, Rohan R. Intrachoroidal neovascularization in transgenic mice overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor in the retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Imamura Y, Noda S, Hashizume K, Shinoda K, Yamaguchi M, Uchiyama S, et al. Drusen, choroidal neovascularization, and retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction in SOD1-deficient mice: a model of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11282–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock H. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman D. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gordon S, Taylor P. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mullins R, Grassi M, Skeie J. Glycoconjugates of choroidal neovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 2005;11:509–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]