Abstract

Background:

Pelvic floor physical therapy is a noninvasive option for relieving pain associated with dyspareunia, genital pain associated with sexual intercourse. Manual therapy is a clinical approach used by physical therapists to mobilize soft tissues, reduce pain, and improve function. To date, the systematic efficacy of manual therapy for treating dyspareunia has not been investigated.

Objective:

To examine the efficacy of manual therapy in reducing pelvic pain among females with dyspareunia.

Study Design:

Systematic review.

Methods:

A systematic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases for articles published between June 1997 and June 2018. Articles were reviewed and selected on the basis of defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The articles were assessed for quality using the PEDro and Modified Downs and Black scales.

Results:

Three observational studies and 1 randomized clinical trial met inclusion criteria. The primary outcome measured was the pain subscale of the Female Sexual Function Index. All studies showed significant improvements in the pain domain of the Female Sexual Function Index (P < .5), corroborating manual therapy as a viable treatment in relieving pain associated with dyspareunia. However, the quality across studies ranged from poor to good.

Conclusions:

Although these findings support the use of manual therapy for alleviating pain with intercourse, few studies exist to authenticate this claim. Moreover, the available studies were characterized by small sample sizes and were variable in methodological quality. More extensive research is needed to establish the efficacy of manual therapy for dyspareunia and the specific mechanisms by which manual therapy is beneficial.

Keywords: dyspareunia, manual therapy, pain, physical therapy

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that approximately 20% to 50% of all women will have dyspareunia at some point in their lives.1 Dyspareunia is defined as recurrent or persistent genital pain associated with sexual intercourse, marking distress or interpersonal difficulty.2 Dyspareunia can manifest in various forms, each classified by the location, time, and nature of the pelvic pain experienced. Deep dyspareunia is pain with deep vaginal penetration, whereas superficial dyspareunia is any pain in the vulvovaginal area during intercourse, particularly on initial penetration.2 Dyspareunia can be generalized when it occurs regardless of partner or situation, and it can be situational when a woman has pain with a specific partner or situation. Finally, primary dyspareunia is pain that has occurred since a woman’s first episode of intercourse, and secondary dyspareunia is pain that occurs after she has already experienced pain-free intercourse.3

Dyspareunia is associated with several different factors and comorbid conditions, including vulvar atrophy, endometriosis, pelvic congestion syndrome, uterine retroversion, adenomyosis, ovarian remnant syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome. Depression, anxiety, and a history of physical or sexual abuse are also associated with the disorder.4 Women who experience dyspareunia may develop fear of pain and pain-related anxiety, leading to avoidance of intercourse and loss of partner intimacy.5

Women diagnosed with dyspareunia are often referred to physical therapists to address any musculoskeletal component of their pain.4 Recently, a systematic review evaluated the efficacy of physical therapist–delivered modalities, such as biofeedback, dilators, and electrical stimulation, to decrease dyspareunia in women with provoked vestibulodynia.6 However, the specific efficacy of manual therapy for dyspareunia has not been systematically appraised. Manual therapy in physical therapist practice involves skilled hands-on techniques intended to increase range of motion, mobilize soft tissue and joints, induce relaxation, reduce pain, and improve function.7 In the area of dyspareunia, manual therapy may include massage, stretching, trigger point therapy, myofascial release, and joint and scar tissue manipulation performed internally and/or externally.8,9 The purpose of this review was to synthesize the literature regarding the efficacy of manual therapy in reducing pelvic pain in females with dyspareunia, as well as identify gaps in the literature to direct future research on this condition.

METHODS

Search Strategy

This systematic review was written in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies.10 To identify appropriate articles for our purpose, a systematic search was performed in 3 electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL) from June 1997 to June 2018. The following key words were used for the search strategy: vaginismus, genito-pelvic pain, penetration disorder, dyspareunia, sexual pain, painful coitus, physical therapy modalities, physical therapy, physiotherapy, rehabilitation, therapy, manual therapy, musculoskeletal manipulations, manipulation, massage, trigger point, myofascial, soft tissue mobilization, joint mobilization, female sexual function index, FSFI, numerical pain rating scale, NPRS, and pain measurement.

Study Selection

Included in this review were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies involving females between the ages of 18 and 75 years who were diagnosed with dyspareunia. Studies selected required the use of manual therapy as a treatment intervention, which may have included massage, trigger point therapy, myofascial release, pelvic manipulation, or graded exposure. Studies were excluded if they were published in a language other than English or included patients who were either male or pregnant or those currently diagnosed with cancer, a sexually transmitted disease, vulvovaginal infection, or a dermatologic condition. Studies were also excluded if manual therapy treatment was combined with any other type of physical therapy (PT) intervention.

Selection Process

After completing the literature search, duplicate articles were removed. Titles and abstracts were then assessed for eligibility independently by 2 team members (R.K., M.B.Y.). A third reviewer (J.T.) assessed the full-text review data and coordinated consensus meetings with senior authors in the event of reviewer disagreement.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two review authors (E.L., M.A.) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies using the PEDro scale11 and Modified Downs and Black scale.12 Any discrepancies were settled in a meeting with a designated third reviewer (J.T.). The randomized clinical trial in the review was assessed with the PEDro scale, obtaining a score based on the number of individual quality criteria from the scale that the study satisfied. The first item, eligibility criteria, is not calculated into the final score, so this tool contains 11 items producing a score out of 10. All nonrandomized studies were assessed with the Modified Downs and Black scale, which addresses the potential for bias in the following areas: reporting, external validity, bias, confounding, and power. Higher overall scores on both the PEDro and Modified Downs and Black scales indicate better quality and lower risk of bias.

RESULTS

Study Selection

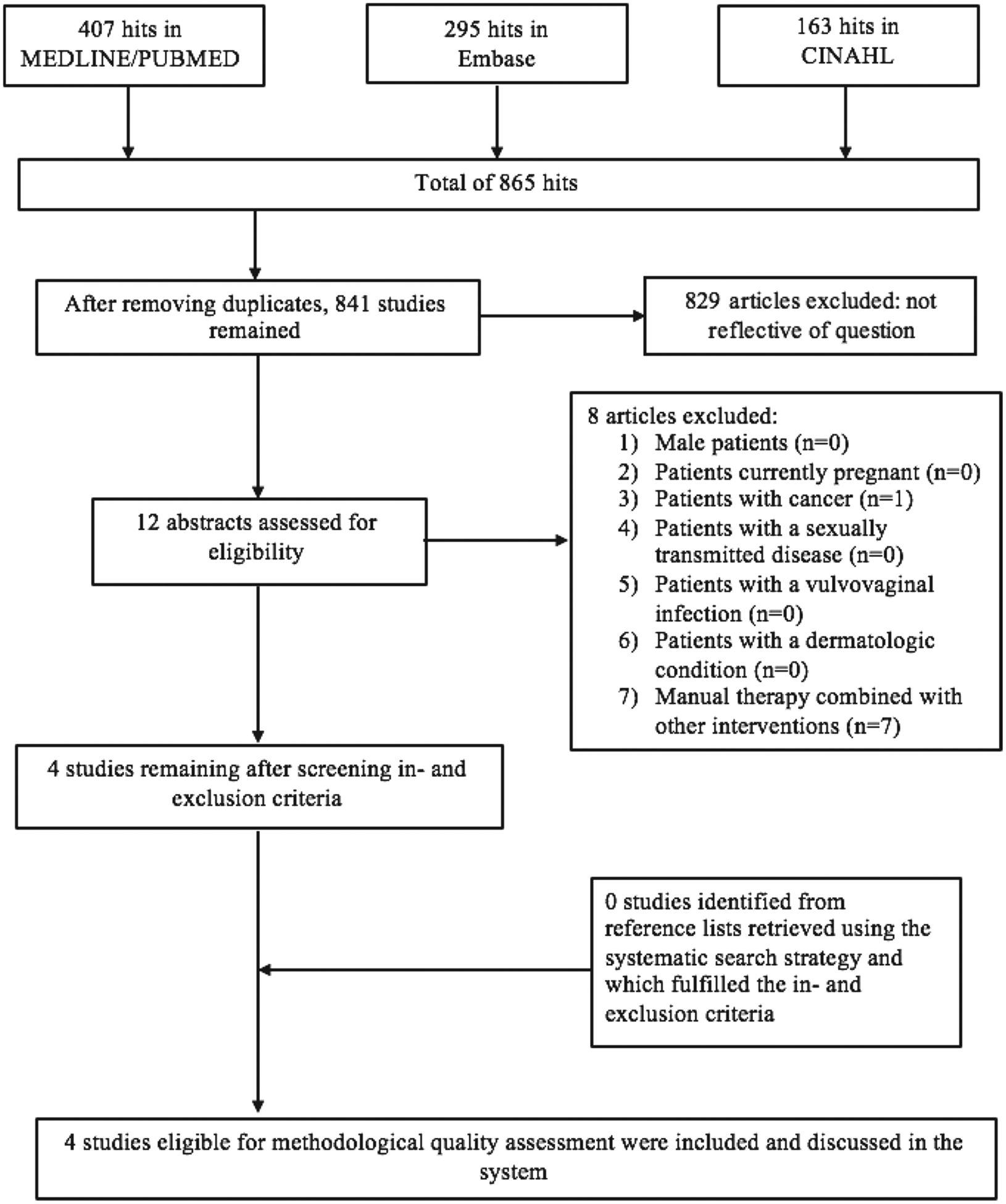

The article selection process is demonstrated in the Figure. The initial search resulted in 870 hits (412 in MEDLINE, 295 in EMBASE, and 163 in CINAHL). After removing duplicates, 846 studies remained. After title/abstract and full-text screening, a total of 4 studies remained.

Figure.

Flowchart study selection.

Summary of Study Results

Study results are summarized in Table 1. Three studies were nonrandomized designs,13,18,20 and only 1 study was prospective in nature. Each of these studies concluded that manual therapy treatment resulted in significant improvement in women with dyspareunia, particularly in terms of sexual dysfunction and pain intensity. Results from the B. F. Wurn et al18 study should be interpreted with caution, as they are based on results from women specifically with endometriosis who participated in the L. J. Wurn et al20 study, generating 2 data sets for the same intervention. One study21 was an RCT. This study also concluded that manual therapy improved sexual function and pain intensity in women with dyspareunia.

Table 1.

Data included from Extracted Studiesa

| Study | Design | n | Age (Range)/Mean | Population | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silva et al (2016)13 | Nonrandomized clinical assay | 8 | (NR)/31.3y | Females with dyspareunia and no CPP (dyspareunia group) | Manual therapy: transvaginal massage using the Thiele method (5-min session; 1x/wk; duration 4 wk) | FSFI,14 VAS,15 McGill Pain Index,16 HADS17 | Improved total FSFI in the dyspareunia group (P < .0001) |

| No change in the total FSFI score in the CPP group (P = .058) | |||||||

| 10 | (NR)/35.0 y | Females with dyspareunia and CPP (CPP group) | |||||

| Improved FSFI pain domain score in the dyspareunia group (P < .0001) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI pain domain score in the CPP group (P = .003) | |||||||

| Improved VAS and McGill Pain Index scores for both groups (P < .05) | |||||||

| No difference in the HADS score for both groups (data not shown) | |||||||

| B. F. Wurn et al (201 l)18 | Study I: Retrospective analysis | 14 | (25–43)/33.8 y | Females with dyspareunia associated with endometriosis | Manual therapy: Wurn technique (20-h total treatment; varied frequency) | FSFI,14 Mankoski Pain Scale19 | Improved total FSFI score (P < .001) |

| Improved FSFI pain domain score (P < .001) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI desire domain score (P = .011) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI arousal domain score (P = .0038) | |||||||

| Study II: Prospective analysis | 18 | (31–43)/37.4 y | Females with dyspareunia and/or dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis | Manual therapy: Wurn technique (20-h total treatment; varied frequency) | Improved FSFI lubrication domain score (P = .010) | ||

| Improved FSFI orgasm domain score (P = .0039) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI satisfaction domain score (P = .0054) | |||||||

| Improved Mankoski Pain Scale “during intercourse” domain score (P = .001) | |||||||

| L. J. Wurn et al (2004)20 | Nonrandomized clinical assay | 23 | (25–43)/33.8 y | Females with dyspareunia with infertility or abdominopelvic pain-related problems | Manual therapy: Uterovesical and myofascial release (20-h total treatment; varied frequency) | FSFI,14 3 supplemental 10-point rating scales of sexual pain levels | Improved total FSFI score (P < .001) |

| Improved FSFI pain domain score (P < .001) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI orgasm domain score (P < .001) | |||||||

| Improved score on all 3 pain scales: | |||||||

| Worst pain (P < .001) | |||||||

| Best pain (P = .002) | |||||||

| Average pain (P < .001) | |||||||

| Secondary outcomes: | |||||||

| Improved FSFI desire domain score (P < .001) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI arousal domain score (P = .0033) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI lubrication domain score (P < .001) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI satisfaction domain score (P < .001) | |||||||

| Zoorob et al (2014)21 | Randomized comparative trial | 29 | (NR)/41.5 y | Females with pelvic floor myalgia and sexual pain | Manual therapy: Levator massage, myofascial/trigger point release, intra-vaginal stretching, and compression maneuvers (six to ten 60-min sessions) | FSFI,14 NRS,22 PGI-I23 | Overall, pain based on the NRS score reduced in both groups as more therapy was administered, but mean change in the NRS score did not differ between groups (P = .8) |

| Number of weeks to report being at least “a little better” were 7.3 (PT group) and 4.4 (LTPI group) (P = .01) | |||||||

| Controlling for the number of treatment sessions, mean change in the NRS score did not differ between groups (P = .4) | |||||||

| Per treatment session, change in the NRS score favored LTPI (P = .01) | |||||||

| Improved total overall FSFI score in both groups, with greater improvement in the PT group (P = .04) | |||||||

| Improved FSFI pain domain score greater in the PT group (P = .02) | |||||||

| PGI-I score did not differ between treatment groups |

Abbreviations: CPP, chronic pelvic pain; FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index; LTPI, levator-directed trigger-point injection; NR, not reported; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement Scale; PT, Physical therapy.

Significance level set to p < .50.

The mean age of participants for all studies was between 31 and 38 years. The presentations of dyspareunia among participants were heterogeneous across the studies; these included dyspareunia associated with chronic pelvic pain (CPP), endometriosis, infertility, and abdominopelvic pain. All studies were characterized by small sample sizes with all less than 30.

Sexual function was measured with the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI).14 The FSFI addresses 6 domains of sexual function, including desire, subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain.14 Total FSFI scores improved in all studies except in those with CPP in the Silva et al13 study, in which only the pain domain of the FSFI showed significant improvement. Pain outcome measures varied across all studies, but each treatment resulted in improved client pain levels at follow-up (Table 1). Outcome measures to assess pain, patient perceived improvement, and emotional experience across studies included the Visual Analog Scale,15 McGill Pain Index,16 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,17 Mankoski Pain Scale,19 Numerical Rating Scale,22 and the Patient Global Impression of Improvement Scale.23

PEDro—Risk of Bias

The RCT by Zoorob et al21 scored a 6/10 on the PEDro risk of bias assessment (Table 2), which equates to “good” quality and internal validity and a low risk of bias.

Table 2.

PEDro Results

| Study | Item Number | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | |

| Zoorob et al21 (2014) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6/10 |

Does not contribute to the total score.

Modified Downs and Black—Risk of Bias

The risk of bias for the nonrandomized trials is shown in Table 3. There was considerable variability in the methodological quality across studies. Scores for nonrandomized studies ranged from below 14/28 to 19/28 (“poor” to “fair” quality), whereas the RCT by Zoorob et al21 scored greater than 20/28, suggesting “good” quality.

Table 3.

Modified Downs and Black Scale Results

| Study | Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting (n = 11) | External Validity (n = 3) | Internal Validity, Bias (n = 7) | Internal Validity, Confounding (n = 6) | Power (n = 1) | Total (n = 28) | |

| Silva et al (2017)13 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 17 |

| B. F. Wurn et al (2011)18 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 19 |

| L. J. Wurn et al (2004)20 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Zoorob et al (2014)21 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 21 |

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

Dyspareunia is a significant health issue, usually involving social, psychological, and physical components.4 Its negative consequences include decreased sexual function, quality of life, and overall health. The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the efficacy of manual therapy for the treatment of dyspareunia in females. While previous studies have shown that physical therapist–delivered treatment may reduce pain experienced during intercourse in women with specific pelvic pain conditions,6 no systematic review has been conducted specific to the efficacy of manual therapy in reducing dyspareunia in females.

The principal finding of this review is a potential reduction in pelvic pain associated with sexual intercourse and a subsequent overall increase in sexual function among females after receiving manual therapy treatment. This improvement was displayed by significantly improved FSFI pain domain scores posttreatment in all 4 studies retrieved.13,18,20,21 In addition, there were significantly improved scores on the Visual Analog Scale, McGill Pain Index, Mankowski Pain Scale, and 10-point pain rating scales in 3 of the studies, further suggesting that pelvic pain specifically associated with sexual intercourse may be alleviated with manual therapy (Table 1).

Different types of manual therapy were applied to subjects in the retrieved studies. Thiele massage, utilized in the Silva et al13 study, consists of transvaginal massage from origin to insertion along the direction of vaginal muscle fibers with an amount of pressure tolerable to the subject. Some of its benefits are that it is relatively easy to learn and carries no risk, so women or their partners can learn Thiele massage and apply it at home, making it an accessible intervention for women who may not be able to afford a regular PT rehabilitation program.24 B. F. Wurn et al18 and L. J. Wurn et al20 utilized techniques that focused on increasing mobility at adhesion sites throughout subjects’ abdomen and pelvis. With this approach, therapists used traction on soft tissue until collagenous cross-links in the musculature were perceived to release and then released the tension of traction either suddenly or gradually depending on the desired effect.20

It is worth noting that in the one RCT included, manual therapy was compared with levator-directed trigger-point injections (LTPI) for treatment of sexual dysfunction and levator-related pelvic pain. The manual therapy used in this study involved pelvic massage and trigger point therapy, specifically utilizing vaginal stretching and compression maneuvers in problem areas. Although both groups reported a reduction in pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction posttreatment, the change in the FSFI pain domain was greater among women treated with manual PT than with LPTI, leading to greater total FSFI scores in the PT group, which signifies greater increased overall sexual function.21 The LTPI group had a shorter time-to-improvement than the PT group, suggesting that LTPI may be more beneficial for individuals seeking improvement in a reduced time frame. While the LTPI group demonstrated more rapid alleviation in pain symptoms, the PT group received a noninvasive treatment with a greater overall amount of pain alleviation. These findings indicate that patient preference should be taken into account when determining treatment options.

L. J. Wurn et al20 published a follow-up study to assess the longevity of the alleviation in dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea after manual therapy treatment with the Wurn technique, which utilizes soft tissue traction to release tension throughout the pelvic musculature.25 Seven of the original 18 patients from study II returned to follow-up at 4 and 12 months posttreatment and reported pain levels with menstruation and intercourse according to the Mankoski Pain Scale. The patients available for follow-up maintained their alleviation in dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea as compared with the pretreatment values. These findings suggest that the Wurn technique may offer a minimally invasive, low-risk option for treatment of dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea, specifically in patients with endometriosis, though poor follow-up in this study dampens the enthusiasm for these findings.

While the results of the included studies suggest that manual therapy may be effective for treating pelvic pain, the methodological quality of available literature is a concern. Every trial scored either “good” or “fair” in the risk of bias assessment, and each of the studies had a small sample size with a range of only 14 to 29 subjects per study. The potential for bias and the range of sample sizes call for caution when interpreting the findings of these studies. The heterogeneity in the types of manual treatment, as well as in the length of time for treatment among subjects, also calls for caution with interpretation of these studies, as it cannot be concluded that there is one specific type of manual therapy or amount of treatment time that is effective for the treatment of dyspareunia.

In addition, results from B. F. Wurn et al18 should be interpreted with caution, as they are based on results from women specifically with endometriosis who participated in the L. J. Wurn et al20 study, generating 2 data sets for the same intervention. Furthermore, in the Silva et al13 study, while both the dyspareunia and CPP groups had significant improvements in the FSFI pain domain score, only the dyspareunia group had significant improvements in the total FSFI score. This reflects the complex causes and symptoms that may be associated with pelvic pain, often requiring therapy interventions that are individualized to each patient.

Clinical Indications

The findings of this systematic review indicate there is limited high-quality evidence that supports manual therapy as an effective treatment of women with dyspareunia. Only one of the 4 studies reviewed was of good methodological quality, whereas the others were of fair-poor quality. In addition, it is unclear which types of manual therapy and treatment times are most effective. At this point, clinicians should recognize that manual therapy may be appropriate for patients with pelvic pain, but personal goals and preferences should be taken into account. For example, if patients are uncomfortable with internal manual therapy, it may be appropriate to teach them how to use a self-management manual therapy tool so that they can perform the intervention privately at home. Dilators and wands can be used for self-treatment, and patients may find that including a partner in the home program is another helpful approach. These alternatives could affect patient satisfaction and improvement over time.

Further literature needs to be published in order to develop established clinical guidelines for managing dyspareunia with manual therapy. This review captured only 4 empirical studies regarding this topic, which is a low number, given the expansion of the women’s health field of PT and its recent media attention for the ways therapists can treat sexual dysfunction. A future RCT may compare the results of different types of manual therapy on females with dyspareunia, such as the Wurn technique versus the Thiele massage. This comparison may guide therapists in the clinic to incorporate either transvaginal massage or traction of soft tissue in their manual therapy work depending on the results of the study. Another trial may study the effects of different durations and frequencies of manual therapy by comparing the outcomes of patients who receive manual therapy 3 times a week for 20 minutes per session and those who receive the same treatment once a week for 60 minutes per session over the course of 6 weeks. The results of such a study could potentially identify ways to minimize health care costs and maximize clinical efficiency.

Limitations of the Review

While this review closely followed PRISMA guidelines10 to minimize bias and produce an adequate synthesis of evidence, some limitations were inevitably present. For example, the lack of current literature on this topic allotted only 4 studies from which to draw conclusions. These studies were characterized by small sample sizes, and 3 of them were non-RCT studies. However, excluding non-RCT studies and those with limited sample size would lead to a limited review of the literature due to a lack of current evidence on this topic. In addition, the search focused solely on dyspareunia, rather than looking at the broad spectrum of conditions associated with persistent pelvic pain. While this could be seen as a limitation, given the small number of studies that were available for review, including a broad search term such as “chronic pelvic pain” would have generated a variety of studies that looked at other causes, obscuring the ability to isolate the effects of manual therapy on pelvic pain associated specifically with dyspareunia.

Reviewing the effects of solely manual therapy, rather than including other interventions (eg, education, therapeutic exercise, modalities), could be seen as a limitation as an isolated therapy intervention may not accurately represent clinical practice, which is multimodal in nature. However, because of the small amount of evidence available regarding the effects of PT intervention on dyspareunia, the review aims to determine the effectiveness of manual therapy alone in order to help develop an optimal multimodal approach as more interventions are examined in the future. Another limitation was the heterogeneity of pain outcome measures, treatment frequency, and follow-up time frame across the studies. The varying outcome measures prevented the determination of how pain intensity changed proportionately among participants in different studies, further limiting the analysis of results. In addition, lack of homogeneity with regard to treatment frequency and follow-up time frame limited the ability to determine an optimal dose of treatment for intervention. Finally, the systematic literature search included only studies published by June 2018; studies published after these date were not included.

Further Research

While the use of manual therapy as treatment of dyspareunia seems promising, more high-quality literature is needed to support the use of manual therapy among pelvic health physical therapists. There is a significant lack of RCTs that evaluate the influence of manual therapy on female pelvic pain. However, one trial by Fitzgerald et al9 studied the feasibility of performing a clinical trial that compared 2 forms of manual treatment (myofascial PT and global therapeutic massage) for urological CPP. Patients were randomized between the 2 treatments, therapist adherence to intervention protocols was excellent, and the rates of withdrawal and severe adverse effects were low. Although this trial did not directly assess whether myofascial PT was superior to massage therapy for CPP, findings suggested that a full clinical trial of myofascial PT is feasible and that this intervention may offer significant clinical benefit to patients with urological CPP.9 Given the feasibility of this study, more randomized studies should be performed, especially those that analyze the effects of different forms of manual therapy.

Future studies must allow for standardization of treatment as well as optimization of therapy according to patient abnormalities. Larger sample sizes in these studies will create a more accurate representation of the population of females with pelvic pain, and longer-term follow-ups will allow researchers to analyze of the sustainability of results. More RCTs may compare the effects of manual therapy in patients with different diagnoses associated with dyspareunia, such as endometriosis or vaginismus. As the research on manual therapy for pelvic pain expands, additional studies may compare manual therapy to other PT approaches, such as education, modalities, and therapeutic exercise. Once these comparisons are explored, therapists can determine optimal interventions and combinations for their patients. Additional studies are warranted to offer practitioners more evidence on which to base clinical decisions, particularly regarding the use of manual therapy as a treatment of dyspareunia in females.

CONCLUSION

Based on this current systematic review of the literature, fair-quality but limited evidence supports that dyspareunia in females may be alleviated with manual therapy. Manual therapy is a noninvasive, nonsurgical intervention that could be an addition to current gynecological and medical treatments of sexual pain. Further implementation of RCTs is necessary to establish the true efficacy of manual therapy and its specific effects on dyspareunia. Future studies with larger sample sizes and additional parameter controls are needed to verify these findings.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the International Consensus Development Conference on Female Sexual Dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163(3):888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binik YM. The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:292–303.doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jean M, Irion GLI. Women’s Health in Physical Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher KA. Management of dyspareunia and associated levator ani muscle overactivity. Phys Ther. 2007;87(7):935–941. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alappattu MJ, Bishop MD. Psychological factors in chronic pelvic pain in women: relevance and application of the fear-avoidance model of pain. Phys Ther. 2011;91 (10):1542–1550. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morin M, Carroll MS, Bergeron S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of physical therapy modalities in women with provoked vestibulodynia. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(3):295–322. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith AR Jr. Manual therapy: the historical, current, and future role in the treatment of pain. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:109–120. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss JM. Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndrome. J Urol. 2001;166(6):2226–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J Urol. 2013;189 (1)(suppl):S75–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centre for Evidence-Based Physiotherapy. PEDro scale. PEDro Web site. https://www.pedro.org.au/wp-content/uploads/PEDro_scale.pdf. Updated June 21, 1999. Accessed August 25, 2017.

- 12.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Silva APM, Pazin C, Salata MC, et al. Assessment of the effectiveness of Thiele massage, sexual function, pain in women with dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2013;10:365. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langley GB, Sheppeard H. The Visual Analogue Scale: its use in pain measurement. Rheumatol Int. 1985;5 (4):145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melzack R The McGill Pain Questionnaire: from description to measurement. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(1):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, Garcia C, Jr Pereira WA. [Mood disorders among inpatients in ambulatory and validation of the anxiety and depression scale HAD]. Rev Saude Publica. 1995;29(5):355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wurn BF, Wurn LJ, Patterson K, Richard King C, Scharf ES. Decreasing dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea in women with endometriosis via a manual physical therapy: results from two independent studies. J Endometriosis. 2011;3(4):188–196. doi: 10.5301/JE.2012.9088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas ME, Randleman ML, DeLane AM, Palmer GA. Determining pain scale preference in a veteran population experiencing chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(3):625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wurn LJ, Wurn BF, King CR, Roscow AS, Scharf ES, Shuster JJ. Increasing orgasm and decreasing dyspareunia by a manual physical therapy technique. MedGenMed. 2004;6(4):47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zoorob D, South M, Karram M, et al. A pilot randomized trial of levator injections versus physical therapy for treatment of pelvic floor myalgia and sexual pain. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(6):845–852. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2606-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan GH, Bushnell MC, Lavigne GJ. Comparison of verbal and visual analogue scales for measuring the intensity and unpleasantness of experimental pain. Pain. 1989;37(3):295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srikrishna S, Robinson D, Cardozo L. Validation of the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) for urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(5):523–528. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Souza Montenegro ML, Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Candido dos Reis FJ,Rosa e Silva JC, Nogueira AA, Poli Neto OB. Thiele massage as a therapeutic option for women with chronic pelvic pain caused by tenderness of pelvic floor muscles. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):981–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wurn LJ. Update on “Decreasing dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea in women with endometriosis via a manual physical therapy: results from 2 independent studies.” J Endometriosis Pelvic Pain Disord. 2014;6(3):161–162. doi: 10.5301/je.5000193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]