ABSTRACT

Mitochondrial dysfunction is behind several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease (AD). Accumulation of damaged mitochondria is already observed at the early stages of AD and has been linked to impaired mitophagy, but the mechanisms underlying this alteration are still not fully known. In our recent study, we show that intracellular cholesterol enrichment can downregulate amyloid beta (Aβ)-induced mitophagy. Mitochondrial glutathione depletion resulting from high cholesterol levels promotes PINK1 (PTEN induced kinase 1)-mediated mitophagosome formation; however, mitophagy flux is ultimately disrupted, most likely due to fusion deficiency of endosomes-lysosomes caused by cholesterol. Meanwhile, in APP-PSEN1-SREBF2 mice, an AD mouse model that overexpresses the cholesterol-related transcription factor SREBF2, cholesterol accumulation prompts an oxidative- and age-dependent cytosolic aggregation of the mitophagy adaptor OPTN (optineurin), which prevents mitophagosome formation despite enhanced PINK1-PRKN/parkin signaling. Hippocampal neurons from postmortem brain of AD individuals reproduce the progressive accumulation of OPTN in aggresome-like structures accompanied by high levels of mitochondrial cholesterol in advanced stages of the disease. Overall, these data provide new insights into the impairment of the PINK1-PRKN mitophagy pathway in AD and suggest the combination of mitophagy inducers with strategies focused on restoring the cholesterol homeostasis and mitochondrial redox balance as a potential disease-modifying therapy for AD.

KEYWORDS: Mitophagy, autophagy, cholesterol, PINK1, parkin, optineurin, aggresomes, Alzheimer disease

Selective autophagic degradation of mitochondria or mitophagy is one of the most important mitochondrial quality control mechanisms. When these processes fail, dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate, compromising cell viability. Thus, and given the high bioenergetics requirement of neurons reliant on mitochondria, it is not surprising to find abnormalities in mitochondria maintenance behind many neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer disease (AD).

We have previously demonstrated that changes in brain cholesterol homeostasis can affect the clearance of MAPT (microtubule associated protein tau) and amyloid-β (Aβ) by impairing macroautophagy/autophagy. According to our findings, the critical factor by which cholesterol influences the metabolism of these 2 key players in AD is most related to increases of the sterol levels in specific compartments within the cell, rather than changes in the total levels. In mitochondria, cholesterol mediates the depletion of glutathione (GSH), stimulating the Aβ-induced oxidative inhibition of the autophagy-related protein ATG4B, which results in increased autophagosome formation. In contrast, the rise of cholesterol in endosomes-lysosomes membranes impairs autophagosome and lysosome fusion ability, resulting in a buildup of MAPT- and Aβ-filled autophagic vesicles and enhanced secretory autophagy of Aβ.

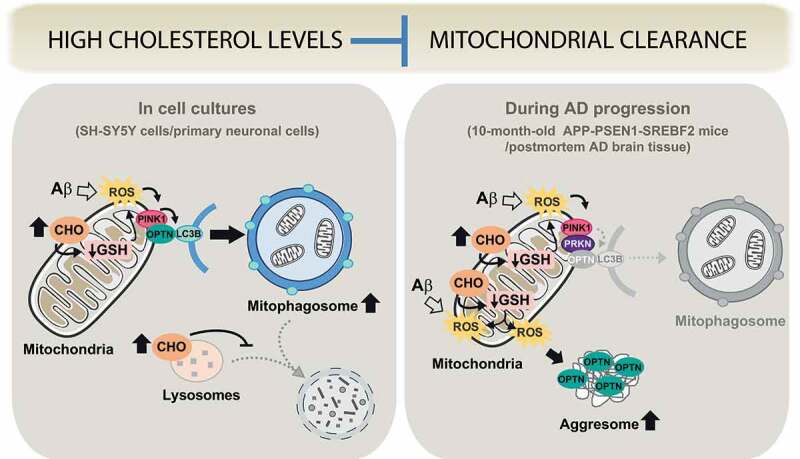

In our recent study [1], we show that high cholesterol can also affect mitophagy (Figure 1). Our data highlight the relevance of the PINK1-PRKN mitophagy pathway in the AD brain. Different mutations in the genes of both the kinase PINK1 and the ubiquitin-ligase PRKN have been described in familial Parkinson disease. Moreover, although basal mitophagy in the brain seems to proceed independently of this molecular pathway, recent works have demonstrated its activation under a pathological burst of mitochondrial stress. It is, therefore, conceivable that mitochondrial cholesterol enrichment through reducing the mitochondrial antioxidant defense may increase the Aβ-induced oxidative stress up to the threshold necessary for PINK-PRKN signaling activation.

Figure 1.

Schema illustrating our proposed model of differential cholesterol (CHO) regulation of mitophagy in in vitro and in vivo AD models. In cholesterol-enriched SH-SY5Y cells and SREBF2 mouse embryonic neurons, Aβ exposure induces a PINK1-mediated and PRKN-independent mitophagy that cannot be properly resolved due to cholesterol-mediated inhibition of mitophagosome-to-lysosome fusion. In contrast, during AD progression (in old APP-PSEN1-SREBF2 mice and postmortem brain tissue of late-stage AD individuals), sustained Aβ-induced mitochondrial damage, exacerbated by cholesterol loading, prevents mitophagosome formation despite PINK1-PRKN signaling induction; in this scenario, the chronic increase of mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes the cytosolic accumulation of the autophagy receptor OPTN (optineurin) in aggresome-like structures, thereby preventing its recruitment to mitochondria and mitophagy progression

We have found that high cholesterol blocks mitophagy in both cell cultures and in vivo in mice expressing APP (amyloid beta precursor protein) with the familial Alzheimer Swedish mutation (Mo/HuAPP695swe) and mutant PSEN1 (presenilin 1; PS1-dE9) together with the active form of SREBF2 (sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2). However, differences are observed depending on the chronicity of cholesterol changes and AD progression. In SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma-derived cells exposed to oligomeric Aβ, cholesterol enrichment stimulates mitophagosomes but causes impairment of mitophagy flux, with a reduction of mitolysosome formation (Figure 1). Similarly, in embryonic neurons from SREBF2 mice, incubation of Aβ favors the mitochondrial stabilization of PINK1 and the subsequent mitophagosome formation, independently of PRKN recruitment. Although a typical mitochondrial insult behind mitophagy induction is the loss of membrane potential, mitophagosome formation in SREBF2 neurons after Aβ exposure occurs without mitochondrial depolarization, in line with recent studies that show that depolarization is not a sufficient condition to induce mitophagy. Moreover, it has been described that early steps of the nascent autophagosome synthesis require a transient generation of mitochondrial ROS. In agreement, treatment with GSH ethyl ester that recovers cholesterol-mediated depletion of mitochondrial GSH significantly lowers the presence of mitophagosomes, thus indicating that mitophagy induction mainly depends on cholesterol-enhanced mitochondrial oxidative stress. These data complement previous studies that illustrate how modulation of the mitochondrial antioxidant protein SOD2 (superoxide dismutase 2) has a direct impact on mitophagy progression, and point to mitochondrial ROS production as an upstream inducer of the process.

In mitochondria from APP-PSEN1-SREBF2 mice, we observe an age-dependent stabilization and activation of PINK1 accompanied by the recruitment of PRKN (Figure 1). High cholesterol loading in hippocampal neurons induces PINK1-mediated accumulation of mitophagosomes but prevents mitophagy completion, reproducing somehow the results obtained in cholesterol-enriched cell cultures. The mitophagy inhibition by cholesterol results in an upregulated mitochondrial content (estimated by analyzing mtDNA copy numbers per diploid nuclear genome), with a negligible contribution of mitochondrial biogenesis to this increase, at least in older ages. Interestingly, and unlike results from cell cultures, mitochondria from APP-PSEN1-SREBF2 mice do not show recruitment of the autophagosomal marker LC3B, despite the engagement of the PINK1-PRKN pathway. A deeper analysis into the nature of these alterations during mice aging unravel a progressive oxidative-mediated aggregation of the autophagy receptor OPTN (optineurin) into large inclusion body-like structures, called aggresomes. In turn, recovery of the mitochondrial pool of GSH, following 2 weeks of GSH ethyl ester treatment, markedly reduces the presence of these aggregates. Cellular inclusions of mutant OPTN have been identified in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/ALS and primary open-angle glaucoma/POAG. It has been reported that oxidative stress stimulates the formation of covalently-bonded oligomers of OPTN, which become sequestered into aggresomes when the ubiquitin-proteasome system fails, as in AD, and are eventually cleared via autophagy. Our findings indicate that the long-term increase of brain cholesterol levels by enhancing oxidative stress and impairing autophagy would favor the formation of OPTN aggregates, thereby preventing OPTN mitochondrial recruitment and mitophagosome formation despite mitophagy induction.

Postmortem brains from individuals with advanced AD phenocopy the same pattern observed in hippocampal sections from elderly APP-PSEN1-SREBF2 mice. Pyramidal neurons in CA3-CA2 layers display OPTN-containing aggresome-like structures in their soma, in parallel with increased levels of mitochondrial cholesterol, becoming more evident at the late stages of the disease.

In conclusion, we describe a link between intracellular cholesterol accumulation and mitophagy impairment in AD. However, while the acute intracellular cholesterol increase in cell cultures prevents mitophagosome maturation, in vivo brain cholesterol loading, with the subsequent exacerbation of mitochondrial oxidative damage during AD progression, promotes OPTN aggregation and directly hampers mitophagosome formation. Thus, specific brain cholesterol-lowering strategies to recover lysosomal function and restrain excessive mitochondrial ROS, in combination with autophagy inducers may be of significance in the treatment of AD.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Fundació la Marató de TV3 [2014-093]; Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (ES) [RTI2018-095572-B-100].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Reference

- [1].Roca-Agujetas V, Barbero-Camps E, De Dios C, et al. Cholesterol alters mitophagy by impairing optineurin recruitment and lysosomal clearance in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16(1):1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]