Abstract

COVID-19, a pandemic disease caused by a viral infection, is associated with a high mortality rate. Most of the signs and symptoms, e.g. cytokine storm, electrolytes imbalances, thromboembolism, etc., are related to mitochondrial dysfunction. Therefore, targeting mitochondrion will represent a more rational treatment of COVID-19. The current work outlines how COVID-19’s signs and symptoms are related to the mitochondrion. Proper understanding of the underlying causes might enhance the opportunity to treat COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, mitochondrion, inflammation, cytokine storm, treatment

Introduction

COVID-19 is a new emerging pulmonary infection caused by SARS-COV-2. It is characterised by flu-like symptoms often followed by acute pulmonary inflammation. Multiple viruses are known to cause both inflammation and mitochondrial dysregulation (metabolic shifts). The influenza virus H1N1 targets the mitochondria of type II cells1. Multiple other inflammatory viruses are known to induce metabolic changes, such as the cytomegalovirus (CMV)2, the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)3, or the hepatitis virus (HCV)4. These viruses interfere with cellular metabolism, increase glucose uptake, and decrease the mitochondrial energy yield resulting in intense glycolysis. In Caco-2 cells, infection with SARS-CoV-2 has been found to up-regulate carbon metabolism and decrease oxidative phosphorylation. I removed it because it is out of context and there is no reference- also no reference for the Caco-2 cells.

The mitochondrion is a doubled-membrane organelle, represents the backbone of the eukaryote cell metabolism5,6. Mitochondrion is the cells' metabolic generator and plays a significant role in determining cellular proliferation7, cellular death pathways8 and also plays a crucial role in maintaining the redox state of the cell9.

Many viral diseases disturb the mitochondrial physiology10–12, e.g. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) affects mitochondrial fission13, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and pseudorabies virus (PRV) affect calcium homeostasis14, and many viruses, e.g. influenza viruses, Hepatitis B virus, support and/or encode proapoptotic proteins that lead to programmed cell death15–17.

Since the occurrence of unidentified pneumonia patients in Wuhan hospitals in China in late 2019 and the labelling of the disease by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the disease became a pandemic in less than three months, and as of the beginning of December 2020 the total confirmed cases of COVID-19 reached 65,257,767 worldwide according to a WHO update18–20.

Despite the increased global incidence records of the COVID-19 cases, most of the infected patients showed either mild infection with no fever or signs of pneumonia or moderate infection with clinical manifestations like cough, sore throat, fever ≥38 °C, fatigue, and shortness of breath21.

Severe infection with increased mortality rate occurs with pneumonia and respiratory failure. At the same time, other complications might present, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), microvascular thrombosis, coagulopathy, liver injury, acute kidney injury, acute cardiac failure and shock22–27. Factors affecting the infection’s severity are not fully understood; however, factors such as the state of the immune system, viral load, and underlying comorbid diseases might play a role in the severity of the infection28–30.

In the current work, we present COVID-19 as a mitochondriopathy and demonstrate that many of the hallmarks of COVID-19 are driven by mitochondrial injury.

The role of mitochondria and cytokine storm

Hyperinflammation – e.g. cytokine storm – is a hallmark of COVID-1931. Such hyper-inflammation occurs due to a massive increase in Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)32,33. Increased ROS results in the release of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin-1β (IL-1β)34,35. The mitochondrion is a significant source of ROS in mammalian cells36. Therefore, the mitochondrion lies within the cytokine storm's core37.

The inflammasome is a cytosolic complex composed of multiple proteins of innate immunity to promote and activate the proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-1838–41. One protein component is an intracellular pathogen sensor called nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors, or NOD-like receptors (NLRs)42. NLRP3 is one NOD-like receptor (NLRs) family member that represents the backbone of the inflammasome. The role of NLRP3 in inflammation and the cytokine storm is crucial and complex. As a consequence of its activation, the cell reprograms its metabolic machinery into increased glycolysis with a subsequent reduction of the Krebs' cycle43, i.e. induces mitochondrial atrophy. ROS also activates the NLRP3 where it is associated with mitochondrial cardiolipin40 and might be correlated with mitochondrial ageing (which stimulates the inflammasome)44.

SARS-COV-2 infection attacks the mitochondrion, especially the phosphorylation (OxPHOS) pathway, e.g. Complex-I45, which results in abnormal ROS production supporting cellular diseases and ageing. SARS-CoV-2 might directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, with consequent flaring-up of the inflammation cascade40. Hence, SARS-COV-2 alters mitochondrial physiology46,47.

COVID-19 disrupts the possible mitochondrial role in iron homeostasis

Iron is an essential nutrient and its levels differ from one tissue to another and also depend on the tissues pathological state48. Cellular iron homeostasis is a complexed process49, but generally, it could be described as: the entrance of iron to the cell through: (i) endocytosis of transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), or (ii) ferrous iron (Fe+2) transporters e.g. divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1)50 and Zinc transporters 8, 14 (ZIP8, ZIP14)51,52 with the assistance of the iron reductase enzyme Metalloreductase STEAP253, Duodenal cytochrome B (Dcytb)52, and Stromal cell-derived receptor 2 (SDR-2)54. After being taken-up, the iron is stored in ferritin55–57 for different biochemical functions including the formation of ROS58,59 and managing transcription through regulating the iron-responsive element-binding proteins (IRP1, IRP2)60,61. After that, iron export from the cell occurs via ferroportin-1 (also termed as solute carrier family 40 member 1 (SLC40A1) or iron-regulated transporter 1 (IREG1))62.

The role of mitochondria in iron homeostasis is one of the most challenging of recently addressed issues. Generally, ferritin is an intracellular protein that can act as an iron-buffering agent to re-equilibrate iron deficiency or iron overload63. Ferritin is stored in the mitochondrion and imported from the cytoplasm via mitoferrin carriers64,65.

Disruption of mitoferrin leads to hyperferritinemia, accompanied by hyper-inflammation, an additional hallmark of COVID-19 severity64,66,67. Severe iron overload leads to mitochondrial DNA damage that exacerbates the cellular oxidative stress68.

For this reason, the iron-chelating agent, Deferoxamine, has been introduced in the management of COVID-1969,70.

Lactate dehydrogenase in COVID-19

The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is an enzyme that catalyses a reversible biochemical reaction that converts pyruvate into lactate. After glucose entry, the hydrogen ions (proton, H+) level is rising, alters the cell's optimum pH to process its chemical pathways. After completing the Krebs' cycle, the cell yields in CO2, energy in ATP, and hydrogen ions. The oxygen reacts with H+ to produce water. Therefore, oxygen in cellular respiration acts as a detoxifying agent (acting as a buffer)71. During transient hypoxia, some tissues, e.g. heart, brain, kidney, are prone to damage.

In contrast, other tissues are slightly adaptable by expressing the lactate dehydrogenase enzyme to shift the cellular metabolism to prevent the Krebs' cycle. Therefore, the glucose utilisation after its entry ends up by forming lactic acid and furthering extracellular acidity via Monocarboxylate Transporters (MCTs)72–74. So, metabolic shifting to end in lactic acid will decrease the possible intracellular acidity and promote the extracellular acidity that exacerbates the cytokine storm as lactate is a signalling molecule that supports inflammation75,76.

The conversion of pyruvate to lactate is associated with the conversion of NADH to NAD+. Increasing of NAD+ level inhibits not only mitochondrial metabolism but also supports the inflammation process77,78.

LDH is correlated with COVID-19 and its severity79 because the lactate synthesis is increased. The level of blood lactate is a prognostic factor for the intensity of the lung's inflammation and decreased survival80.

Dysregulation of calcium homeostasis during COVID-19 affects mitochondrial biology

Calcium is a vital electrolyte that plays many critical roles in cellular physiology81. Calcium governs intracellular mitochondrial motility (mitochondrial dynamics)82,83, manages mitophagy84–86, controls ATP production87, and impacts the role of the mitochondrion in the redox statue of the cell88.

A reduced level of calcium is well-documented in covid-19 infection, and it is thought to have a role in its poor prognosis89. Therefore, hypocalcaemia has a detrimental effect on the mitochondrion, promotes ROS formation, and activates the inflammatory cascade.

The role of the mitochondrion on coagulability

D-dimer

While the term D-dimer reflects the dimerisation process (two subunits), it also seems to be an erroneous name suggested by one of the researchers that discovered it90,91. All in all, D-dimer is fibrin fragments that are crosslinked with polypeptide bonds due to the degradation of fibrinogen via plasmin92,93. Higher levels of D-dimer in the blood represent a severe sign of thromboembolism94–96 and recently has become an indicator of how COVID-19 patients develop thromboembolism and the disease severity97–99 since D-dimer level is markedly increased among critical patients and is a significant risk factor for mortality100

Oxidative stress is associated with thromboembolism101, in that ROS activates urokinase plasminogen activator (UPA)102, subsequently producing plasmin that hydrolyses fibrinogen into D-dimer. The increased Plasmin, in turn, increases ROS103, which produces an out-of-control positive feedback between ROS and plasmin. Furthermore, D-dimer expression also might increase the level of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (plasmin activator), and so it also enters a vicious cycle producing thromboembolism.

There is an inverse relationship between functional mitochondrial and urokinase plasminogen, such that upregulation of the UPA is an indicator of reduced mitochondrial function while, in contrast, downregulation of UPA restores mitochondrial function (e.g. activation of programmed cell death)103.

Troponins

These are a group of proteins found in the heart and skeletal muscle that mediate calcium-dependent muscle contraction104,105. An increased level of troponins in the blood is an indicator of necrosis rather than programmed cell death, i.e. mitochondrial injury or dysfunctionality due to hypoxia106–112.

COVID-19 is associated with higher troponin levels113, which might correlate with mortality114. Indeed, higher troponin levels were confined to cardiac disorder and other diseases, such as sepsis or renal disease115, both of which were correlated with COVID-19112,116,117. Also, during cardiac and muscle injury, troponin levels are increased significantly in severe disease patients, leading to progression towards multiple organ failure (MOF) and death.

Targeting the mitochondrion to treat COVID-19

In 1956, Otto Warburg suggested that cancer occurs due to mitochondrial injury and, in this respect, it seems that COVID-19 could be looked at as an extrapolation of cancer118. At least it could be analysed through Warburg's lens and could stimulate the debate of whether mitochondriopathy is a direct cause of COVID-19 via SARS-COV-2 infection or just a symptom of COVID-19 in which, at least, mitochondrial injury might represent an early step of the SARS-COV-2 disease cascade. In this regard, the administration of pharmacological and non-pharmacological modulators of mitochondrial function119 could enhance patient recovery and improve patients' quality of life and might boost the vaccine's efficacy in the aged population (mitochondrial is a hub of ageing). An example of those agents includes:

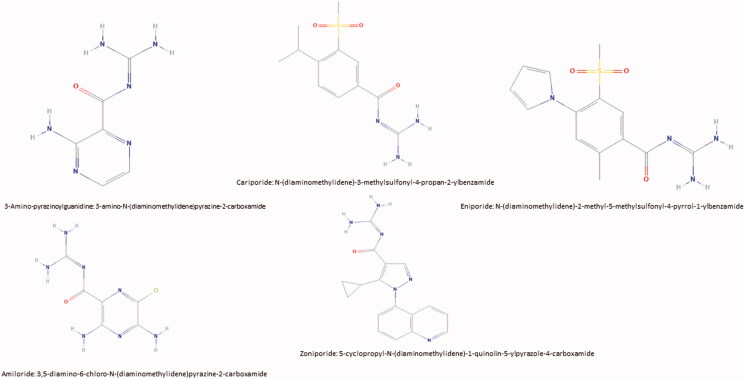

- NHE1 inhibitors:

- In 2000, Reshkin et al. observed that the over-expression of NHE1 is the first event of carcinogenesis followed by alkaline increases in intracellular pH (alkaline pHi)120,121; and alkaline pHi results in mitochondrial atrophy. Therefore, NHE1 inhibition, and specifically mitochondrial NHE1, will boost the mitochondrial functionality122 and so decrease the effect of SARS-COV-2.

- Amiloride also has potential as an anti-cytokine storm agent124. One of the possible mechanisms of action that explains how Amiloride antagonises the cytokine storm via contrasting the effect of proinflammatory mediators (e.g. the NF-κB transcription factor), by boosting the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators such as Interleukin-10 (IL-10), and nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (IκBα)124 (see Figure 1).

- Fermented wheat germ extract:

- Fermented wheat germ extract (FWGE) is a dietary supplement used to treat cancer and to slow ageing. The mode of action of FWGE is a mitochondrial restoration agent as it modulates the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex to support the production of ATP from mitochondria128. Also, FWGE inhibits LDH and reduces the NAD+ levels128. Moreover, it shows promising action as an anti-cytokine storm drug129–131.

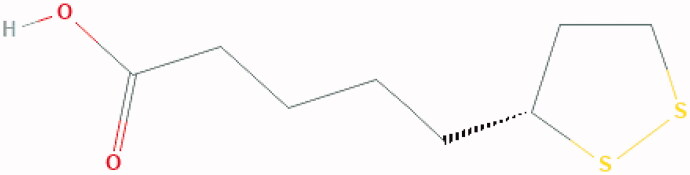

- α-lipoic acid:

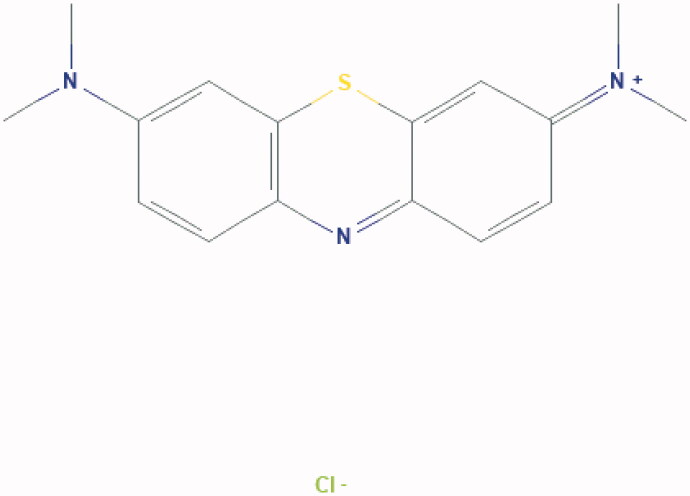

- Methylene Blue

- Methylene Blue is the oldest of synthetic drugs (Figure 4), even before aspirin. Heinrich Carro manufactured it in 1876 for the German firm BASF. Methylene blue is a simple molecule. The fusion of two benzene rings with one nitrogen and one sulphur atom leads to a tricyclic aromatic compound which has a complex pharmacology and multiple clinical indications. Its mechanism of action involves a stabilising effect on mitochondria. Also, Methylene blue inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2136 and we reported a cohort of patients treated for cancer by Methylene Blue in cases without SARS-CoV-2137.

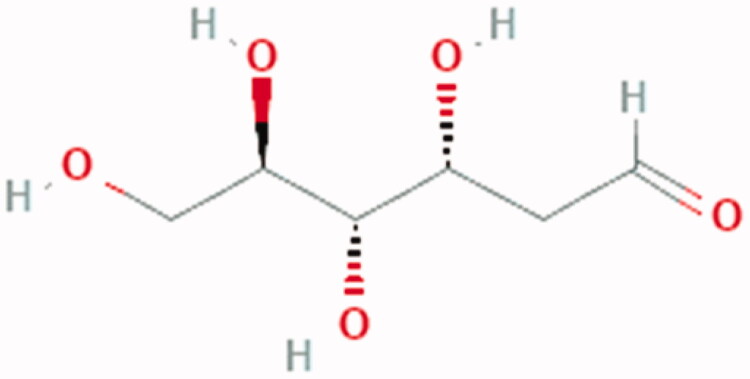

- 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG)

- The German scientist Otto Warburg discovered the Warburg effect in the 1920s138. Warburg stated that cancer cells display increased glycolysis and lactic acid secretion and, opposite to normal cells, the presence of oxygen does not inhibit this fermentation. The advent of Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan combined with radio-labelled fluorodeoxyglucose has revived interest in the Warburg effect as there is an increased uptake of labelled glucose in the primary tumour and its distant metastases. The Warburg effect explains some of the cancer's hallmarks118,135 shift to aerobic glycolysis that has been reported to stimulate cell growth, evade tumour suppression, and resist cell death139. Increased pressure resulting from unrelenting proliferation in the affected organ's limited space results in cells' extrusion in the vasculature and distant metastases. The release of lactic acid in the extracellular space is a consequence of the Warburg effect. Lactic acid promotes angiogenesis and immune cell modulation140.

- The Warburg hypothesis was based on mitochondrial injury, but the debate is whether it is a cause of malignant transformation or just a consequence. Irrespective of which is correct, mitochondrial damage supports evolutionary tumour trajectory142. Parallel to this context, COVID-19 is associated with mitochondrial injury and such injury supports SARS-COV-2 pathogenicity and confers its evolutionary advantage. However, a significant concern is whether COVID-19 patients will develop cancer in the future due to such mitochondrial injury?

Figure 1.

How does Amiloride re-equilibrate the cytokine storm via boosting the anti-inflammatory cytokines and suppressing the proinflammatory cytokines.

Figure 2.

Different chemical formula of some of NHE1 inhibitors.

Figure 3.

Chemical Structure of lipoic acid: 5-[(3R)-dithiolan-3-yl] pentanoic acid.

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of methylene blue: [7-(dimethylamino) phenothiazin-3-ylidene]-dimethylazanium;chloride.

Figure 5.

Chemical Structure of 2DG: (3 R,4S,5R)-3,4,5,6-tetrahydroxyhexanal.

Recommendations and concluding remarks

COVID-19 has become a pandemic disease. The biology of the disease is exceptionally intricate, including many overlapping pathways. However, while the mitochondrion lies at the core of these pathways, its importance demands immediate attention and further investigation. A proper understanding of mitochondrial biology in COVID-19 pathogenesis will significantly enhance the strategy of fighting SARS-COV-2 (Figure 6). This paper has discussed and suggests a couple of pharmacological modulators that might represent potentially promising anti-COVID-19 treatments to block its progression and alleviate its aggressiveness.

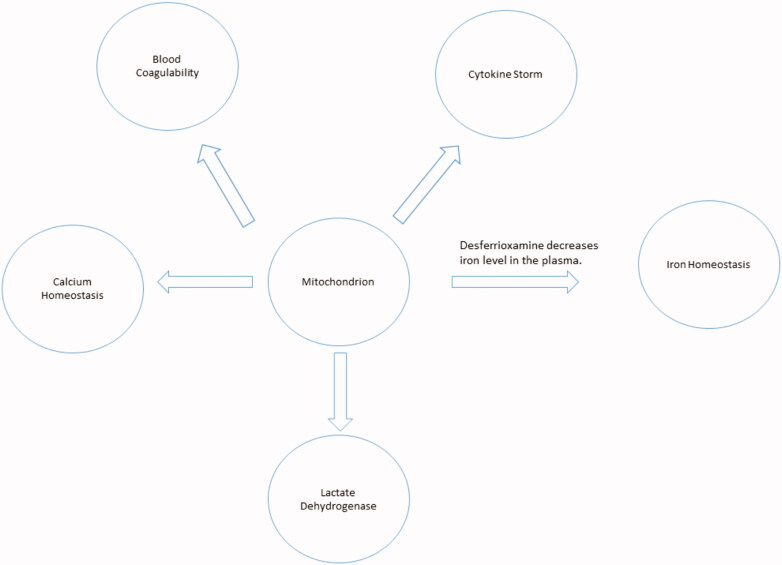

Figure 6.

The mitochondrion lies within the core of COVID-19 cardinals.

Author contributions

KOA contributed to the conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, software, writing (original draft). SJR contributed to the supervision, conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, software, writing (review and editing). STA, AH, and LS contributed to the conceptualisation, data curation, resources, writing (original draft). ASA, SBMA, AMA, and SSA contributed to methodology, resources, software. AKM, HA, AHHB, and MI contributed to the investigation, methodology, visualisation. SH, MR, and RAC contributed to investigation, methodology, and resources. SH also contributed to review and correct the final text.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Davis I, Doolittle L, Guttridge D, et al. H1N1 influenza A virus infection of mice induces the warburg effect in ATII cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:A3842. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Y, Clippinger AJ, Alwine JC.. Viral effects on metabolism: changes in glucose and glutamine utilization during human cytomegalovirus infection. Trends Microbiol 2011;19:360–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darekar S, Georgiou K, Yurchenko M, et al. Epstein-barr virus immortalization of human B-cells leads to stabilization of hypoxia-induced factor 1 alpha, congruent with the Warburg effect. PLoS One 2012;7:e42072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ripoli M, D'Aprile A, Quarato G, et al. Hepatitis C virus-linked mitochondrial dysfunction promotes hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-mediated glycolytic adaptation. J Virol 2010;84:647–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabaldón T, Huynen MA.. From endosymbiont to host-controlled organelle: the hijacking of mitochondrial protein synthesis and metabolism. Subramaniam S, ed. PLoS Comput Biol 2007;3:e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittis AA, Gabaldón T.. Late acquisition of mitochondria by a host with chimaeric prokaryotic ancestry. Nature 2016;531:101–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan XJ, Yu X, Wang XP, et al. Mitochondria play an important role in the cell proliferation suppressing activity of berberine. Sci Rep 2017;7:41712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Ouchida AT, Norberg E.. The role of mitochondria in metabolism and cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;482:426–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handy DE, Loscalzo J.. Redox regulation of mitochondrial function. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012;16:1323–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reshi L, Wang H-V, Hong J-R.. Modulation of mitochondria during viral infections. In: Taskin E, Guven C, eds. Mitochondrial diseases. London: InTech; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan M, Syed GH, Kim SJ, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics and viral infections: a close nexus. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015;1853:2822–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiku V, Tan MW, Dikic I.. Mitochondrial functions in infection and immunity. Trends Cell Biol 2020;30:263–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young LS, Rickinson AB.. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:757–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer T, Enquist LW.. Alphaherpesvirus infection disrupts mitochondrial transport in neurons. Cell Host Microbe 2012;11:504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takada S, Shirakata Y, Kaneniwa N, et al. Association of hepatitis B virus X protein with mitochondria causes mitochondrial aggregation at the nuclear periphery, leading to cell death. Oncogene 1999;18:6965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennet T, Peterhans E, Stocker R.. Alterations in antioxidant defences in lung and liver of mice infected with influenza A virus. J General Virol 1992;73:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henkler F, Hoare J, Waseem N, et al. Intracellular localization of the hepatitis B virus HBx protein. J General Virol 2001;82:871–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinze G, Schemper M.. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2002;21:2409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet 2020;395:809–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anon . WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/ [accessed 5 Dec 2020].

- 21.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New Engl J Med 2020;382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez-Recalde Á, Solano-López J, Miguelena-Hycka J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiogenic shock. Different cardiovascular presentations with high mortality. Revista Española de Cardiología 2020;73:669–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du R-H, Liang L-R, Yang C-Q, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020;55:2000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang HJ, Zhang YM, Yang M, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2002439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciceri F, Ruggeri A, Lembo R, et al. Decreased in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Pathogens Global Health 2020;114:281–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paek JH, Kim Y, Park WY, et al. Severe acute kidney injury in COVID-19 patients is associated with in-hospital mortality. Hirst JA, ed. PLoS One 2020;15:e0243528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malas MB, Naazie IN, Elsayed N, et al. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2020;29-30:100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:811–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in Critically ill patients in the seattle region – case series. New Engl J Med 2020;382:2012–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng S, Fan J, Yu F, et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January. Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coperchini F, Chiovato L, Croce L, et al. The cytokine storm in COVID-19: an overview of the involvement of the chemokine/chemokine-receptor system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2020;53:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, et al. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:1126–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naha PC, Davoren M, Lyng FM, et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced cytokine production and cytotoxicity of PAMAM dendrimers in J774A.1 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010;246:91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang D, Elner SG, Bian ZM, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines increase reactive oxygen species through mitochondria and NADPH oxidase in cultured RPE cells. Exp Eye Res 2007;85:462–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamata H, Honda SI, Maeda S, et al. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFα-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 2005;120:649–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J 2009;417:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saleh J, Peyssonnaux C, Singh KK, et al. Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Mitochondrion 2020;54:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature 2004;430:213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broz P, Dixit VM.. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:407–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J.. The Inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-β. Mol Cell 2002;10:417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sui A, Chen X, Shen J, et al. Inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome with MCC950 ameliorates retinal neovascularization and leakage by reversing the IL-1β/IL-18 activation pattern in an oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy mouse model. Cell Death Dis 2020;11:901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw MH, Reimer T, Kim YG, et al. NOD-like receptors (NLRs): bona fide intracellular microbial sensors. Curr Opin Immunol 2008;20:377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JPY.. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol 2019;19:477–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kauppinen A. Mitochondria-associated inflammasome activation and its impact on aging and age-related diseases. In: Fulop T, Franceschi C, Hirokawa K, Pawelec G, eds. Handbook of immunosenescence. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouyang L, Gong J.. Mitochondrial-targeted ubiquinone: a potential treatment for COVID-19. Med Hypotheses 2020;144:110161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh KK, Chaubey G, Chen JY, et al. Decoding sars-cov-2 hijacking of host mitochondria in covid-19 pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020;319:C258–C267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganji R, Reddy PH.. Impact of COVID-19 on mitochondrial-based immunity in aging and age-related diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2020;12:614650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao N, Enns CA.. Iron transport machinery of human cells, players and their interactions. In: Orlov S, ed. Current topics in membranes. Vol. 69. San Diego: Academic Press Inc.; 2012:67–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins JF, Anderson GJ.. Molecular mechanisms of intestinal iron transport. In: Johnson LR, ed. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Vol. 2. London: Elsevier Inc.; 2012:1921–1947. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garrick MD. Human iron transporters. Genes Nutr 2011;6:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liuzzi JP, Aydemir F, Nam H, et al. Zip14 (Slc39a14) mediates non-transferrin-bound iron uptake into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:13612–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKie AT, Barrow D, Latunde-Dada GO, et al. An iron-regulated ferric reductase associated with the absorption of dietary iron. Science 2001;291:1755–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ji C, Kosman DJ.. Molecular mechanisms of non-transferrin-bound and transferring-bound iron uptake in primary hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem 2015;133:668–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vargas JD, Herpers B, McKie AT, et al. Stromal cell-derived receptor 2 and cytochrome b561 are functional ferric reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003;1651:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackenzie EL, Iwasaki K, Tsuji Y.. Intracellular iron transport and storage: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid Redox Signal 2008;10:997–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arosio P, Elia L, Poli M.. Ferritin, cellular iron storage and regulation. IUBMB Life 2017;69:414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Domenico I, McVey Ward D, Kaplan J.. Regulation of iron acquisition and storage: consequences for iron-linked disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bystrom LM, Guzman ML, Rivella S.. Iron and reactive oxygen species: friends or foes of cancer cells? Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:1917–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dixon SJ, Stockwell BR.. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol 2014;10:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cairo G, Recalcati S.. Iron-regulatory proteins: molecular biology and pathophysiological implications. Exp Rev Mol Med 2007;9:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou ZD, Tan EK.. Iron regulatory protein (IRP)-iron responsive element (IRE) signaling pathway in human neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurodegener 2017;12:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yanatori I, Richardson DR, Imada K, et al. Iron export through the transporter ferroportin 1 is modulated by the iron chaperone PCBP2. J Biol Chem 2016;291:17303–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daru J, Colman K, Stanworth SJ, et al. Serum ferritin as an indicator of iron status: what do we need to know? Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:1634S–9S. Vol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paradkar PN, Zumbrennen KB, Paw BH, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial iron import through differential turnover of mitoferrin 1 and mitoferrin 2. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29:1007–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shaw GC, Cope JJ, Li L, et al. Mitoferrin is essential for erythroid iron assimilation. Nature 2006;440:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao G, Chang YZ.. Mitochondrial ferritin in the regulation of brain iron homeostasis and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Pharmacol 2014;5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen C, Paw BH.. Cellular and mitochondrial iron homeostasis in vertebrates. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1823:1459–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walter PB, Knutson MD, Paler-Martinez A, et al. Iron deficiency and iron excess damage mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:2264–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vlahakos VD, Marathias KP, Arkadopoulos N, et al. Hyperferritinemia in patients with COVID‐19: an opportunity for iron chelation? Artif Organs 2021;45:163–7. aor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abobaker A. Can iron chelation as an adjunct treatment of COVID-19 improve the clinical outcome? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2020;76:1619–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alfarouk KO, Verduzco D, Rauch C, et al. Glycolysis, tumor metabolism, cancer growth and dissemination. A new pH-based etiopathogenic perspective and therapeutic approach to an old cancer question. Oncoscience 2014;1:777–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alfarouk KO. Tumor metabolism, cancer cell transporters, and microenvironmental resistance. J Enzyme Inhibit Med Chem 2016;31:859–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hertz L, Dienel GA.. Lactate transport and transporters: general principles and functional roles in brains cells. J Neurosci Res 2005;79:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bosshart PD, Kalbermatter D, Bonetti S, et al. Mechanistic basis of L-lactate transport in the SLC16 solute carrier family. Nature Commun 2019;10:2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haas R, Smith J, Rocher-Ros V, et al. Lactate regulates metabolic and proinflammatory circuits in control of T cell migration and effector functions. PLoS Biol 2015;13:e1002202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pucino V, Bombardieri M, Pitzalis C, et al. Lactate at the crossroads of metabolism, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol 2017;47:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gerner RR, Klepsch V, Macheiner S, et al. NAD metabolism fuels human and mouse intestinal inflammation. Gut 2018;67:1813–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adriouch S, Hubert S, Pechberty S, et al. NAD + released during inflammation participates in T cell homeostasis by inducing ART2-mediated death of naive T cells in vivo. J Immunol 2007;179:186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henry BM, Aggarwal G, Wong J, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase levels predict coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality: a pooled analysis. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:1722–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Booth AL, Abels E, McCaffrey P.. Development of a prognostic model for mortality in COVID-19 infection using machine learning. Modern Pathol 2021;34:522–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Romero-Garcia S, Prado-Garcia H.. Mitochondrial calcium: transport and modulation of cellular processes in homeostasis and cancer (Review). Int J Oncol 2019;54:1155–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Paupe V, Prudent J.. New insights into the role of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;500:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Contreras L, Drago I, Zampese E, et al. Mitochondria: the calcium connection. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1797:607–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, et al. PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Mol Cell 2009;33:627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dagda RK, Cherra SJ, Kulich SM, et al. Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem 2009;284:13843–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gelmetti V, De Rosa P, Torosantucci L, et al. PINK1 and BECN1 relocalize at mitochondria-associated membranes during mitophagy and promote ER-mitochondria tethering and autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2017;13:654–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jouaville LS, Pinton P, Bastianutto C, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by calcium: evidence for a long-term metabolic priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:13807–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kennedy ED, Rizzuto R, Theler JM, et al. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion correlates with changes in mitochondrial and cytosolic Ca2+ in aequorin-expressing INS-1 cells. J Clin Invest 1996;98:2524–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang C, Ma X, Wu J, et al. Low serum calcium and phosphorus and their clinical performance in detecting COVID‐19 patients. J Med Virol 2021;93:1639–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gaffney PJ, Brasher M.. Subunit structure of the plasmin-induced degradation products of crosslinked fibrin. BBA 1973;295:308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gaffney PD. dimer. History of the discovery, characterisation and utility of this and other fibrin fragments. Fibrinol Proteol 1993;7:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Haverkate F, Timan G.. Protective effect of calcium in the plasmin degradation of fibrinogen and fibrin fragments D. Thrombosis Res 1977;10:803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Favresse J, Lippi G, Roy P-M, et al. D-dimer: preanalytical, analytical, postanalytical variables, and clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2018;55:548–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kelly J, Rudd A, Lewis RR, et al. Plasma D-dimers in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:747–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pulivarthi S, Gurram MK.. Effectiveness of D-dimer as a screening test for venous thromboembolism: an update. North Am J Med Sci 2014;6:491–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Matsuo H, Nakajima Y, Ogawa T, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in screening deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized japanese patients with acute medical diseases/Episodes. Ann Vasc Dis 2016;9:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cho ES, McClelland PH, Cheng O, et al. Utility of D-dimer for diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis in coronavirus disease-19 infection. J Vasc Surg 2021;9:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu HH, Qin C, Chen M, et al. D-dimer level is associated with the severity of COVID-19. Thrombosis Res 2020;195:219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yao Y, Cao J, Wang Q, et al. D-dimer as a biomarker for disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a case control study. J Intens Care 2020;8:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang Q, Zennadi R.. Oxidative stress and thrombosis during aging: the roles of oxidative stress in RBCS in venous thrombosis. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee KH, Kim JR.. Reactive oxygen species regulate the generation of urokinase plasminogen activator in human hepatoma cells via MAPK pathways after treatment with hepatocyte growth factor. Exp Mol Med 2009;41:180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tykhomyrov AA, Zhernosekov DD, Guzyk MM, et al. Plasminogen modulates formation of reactive oxygen species in human platelets. Ukrain Biochem J 2018;90:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wijnker PJM, Sequeira V, Foster DB, et al. Length-dependent activation is modulated by cardiac troponin I bisphosphorylation at Ser23 and Ser24 but not by Thr143 phosphorylation. Am J Physiol 2014;306:H1171–H1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sun YB, Lou F, Irving M.. Calcium- and myosin-dependent changes in troponin structure during activation of heart muscle. J Physiol 2009;587:155–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Korff S, Katus HA, Giannitsis E.. Differential diagnosis of elevated troponins. Heart 2006;92:987–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Skeik N, Patel DC.. A review of troponins in ischemic heart disease and other conditions. Int J Angiol 2007;16:53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Daubert MA, Jeremias A.. The utility of troponin measurement to detect myocardial infarction: review of the current findings. Vasc Health Risk Manage 2010;6:691–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Okamoto R, Hirashiki A, Cheng XW, et al. Usefulness of serum cardiac troponins T and I to predict cardiac molecular changes and cardiac damage in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int Heart J 2013;54:202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pankuweit S, Richter A.. Mitochondrial disorders with cardiac dysfunction: an under-reported aetiology with phenotypic heterogeneity. Eur Heart J. 36:2894–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Amgalan D, Pekson R, Kitsis RN.. Troponin release following brief myocardial ischemia: apoptosis versus necrosis. JACC 2017;2:118–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Park KC, Gaze DC, Collinson PO, et al. Cardiac troponins: from myocardial infarction to chronic disease. Cardiovasc Res 2017;113:1708–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tersalvi G, Vicenzi M, Calabretta D, et al. Elevated troponin in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: possible mechanisms. J Cardiac Fail 2020;26:470–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lombardi CM, Carubelli V, Iorio A, et al. Association of troponin levels with mortality in italian patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019: results of a multicenter study. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1274–E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mannu GS. The non-cardiac use and significance of cardiac troponins. Scott Med J 2014;59:172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Collado S, Arenas MD, Barbosa F, et al. COVID-19 in grade 4–5 chronic kidney disease patients. Kidney Blood Pressure Res 2020;45:768–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ajaimy M, Melamed ML.. Covid-19 in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;15:1087–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Alfarouk KO, Shayoub MEA, Muddathir AK, et al. Evolution of tumor metabolism might reflect carcinogenesis as a reverse evolution process (dismantling of multicellularity). Cancers 2011;3:3002–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Andreux PA, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J.. Pharmacological approaches to restore mitochondrial function. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 2013;12:465–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Reshkin SJ, Bellizzi A, Caldeira S, et al. Na+/H+ exchanger-dependent intracellular alkalinization is an early event in malignant transformation and plays an essential role in the development of subsequent transformation-associated phenotypes. FASEB J 2000;14:2185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cardone RAR, Alfarouk KOK, Elliott RLR, et al. The role of sodium hydrogen exchanger 1 in dysregulation of proton dynamics and reprogramming of cancer metabolism as a sequela. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alvarez BV, Villa-Abrille MC.. Mitochondrial NHE1: a newly identified target to prevent heart disease. Front Physiol 2013;4:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wilson L, Gage P, Ewart G.. Hexamethylene amiloride blocks E protein ion channels and inhibits coronavirus replication. Virology 2006;353:294–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Haddad JJ, Land SC.. Amiloride blockades lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis in an IκB-α/NF-κB-dependent mechanism: evidence for the amplification of an antiinflammatory pathway in the alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jankun J, Skrzypczak-Jankun E.. Molecular basis of specific inhibition of urokinase plasminogen activator by amiloride. Cancer Biochem Biophys 1999;17:109–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vassalli JD, Belin D.. Amiloride selectively inhibits the urokinase-type plasminogen activator. FEBS Lett 1987;214:187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Javadov S, Choi A, Rajapurohitam V, et al. NHE-1 inhibition-induced cardioprotection against ischaemia/reperfusion is associated with attenuation of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Cardiovasc Res 2007;77:416–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bencze G, Bencze S, Rivera KD, et al. Mito-oncology agent: fermented extract suppresses the Warburg effect, restores oxidative mitochondrial activity, and inhibits in vivo tumor growth. Sci Rep 2020;10:14174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mueller T, Voigt W.. Fermented wheat germ extract – nutritional supplement or anticancer drug? Nutr J 2011;10:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sukkar SG, Cella F, Rovera GM, et al. A multicentric prospective open trial on the quality of life and oxidative stress in patients affected by advanced head and neck cancer treated with a new benzoquinone-rich product derived from fermented wheat germ (Avemar). Mediterranean J Nutr Metab 2008;1:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jeong H-Y, Choi Y-S, Lee J-K, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of citric acid-treated wheat germ extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Nutrients 2017;9:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mijnhout GS, Kollen BJ, Alkhalaf A, et al. Alpha lipoic acid for symptomatic peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Endocrinol 2012;2012:2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhong M, Sun A, Xiao T, et al. A randomized, single-blind, group sequential, active-controlled study to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of α-Lipoic acid for critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). medRxiv 2020:2020.04.15.20066266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Schwartz L, Seyfried T, Alfarouk KO, et al. Out of Warburg effect: an effective cancer treatment targeting the tumor specific metabolism and dysregulated pH. Semin Cancer Biol 2017;43:134–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schwartz L, Supuran CT, Alfarouk KO.. The Warburg effect and the hallmarks of cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem 2017;17:164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gendrot M, Andreani J, Duflot I, et al. Methylene blue inhibits replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;56:106202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Henry M, Summa M, Patrick L, et al. A cohort of cancer patients with no reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection: the possible preventive role of Methylene Blue. Substantia 2020;4:888. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956;123:309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB.. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009;324:1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Dhup S, Dadhich RK, Porporato PE, et al. Multiple biological activities of lactic acid in cancer: influences on tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Curr Pharm Des 2012;18:1319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ayres JS. A metabolic handbook for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Metab 2020;2:572–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Alfarouk KO, Muddathir AK, Shayoub MEA.. Tumor acidity as evolutionary spite. Cancers 2011;3:408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]