Abstract

Background:

In societies around the world, international migration and growing economic inequality have contributed to heightened perceptions of intergroup threat (i.e., feeling that people outside of one’s social group are hostile to their physical or emotional well-being). Exposures related to intergroup threat, like negative intergroup contact, are inherently stressful and may contribute to higher levels of psychological distress in the population. This longitudinal study investigated whether maternal experiences of negative intergroup contact are related to poor mental health outcomes among ethnically diverse children.

Methods:

Data are from 4,025 mother-child pairs in the Generation R Study, a multi-ethnic Dutch birth cohort initiated in 2005. Mothers’ experiences of negative intergroup contact were assessed during pregnancy. Child mental health was indexed by problem behavior reported by parents and teachers using the Child Behavior Checklist. Linear mixed-effects models tested longitudinal associations of maternal-reported negative intergroup contact with child problem behavior reported by mothers at ages 3, 5, and 9 years, considering a range of potential confounders. Sensitivity analyses examined whether results were replicated using child data from other informants.

Results:

In fully adjusted models, higher levels of negative intergroup contact were associated with more problem behavior averaged across childhood for both non-Dutch (standardized B=0.10, 95% CI=0.05, 0.14) and Dutch children (standardized B=0.12, 95% CI=0.08, 0.15). Sensitivity analyses with child data from other informants largely supported primary findings.

Conclusions:

Comparable adverse intergenerational effects on mental health were observed among both ethnic minority and ethnic majority children whose mothers experienced negative intergroup contact. These findings suggest that ethnically divisive social contexts may confer widespread risks, regardless of a child’s ethnic background. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine exposures related to intergroup threat from an epidemiologic perspective and provides proof of principle that such exposures may be informative for population health.

Keywords: social epidemiology, discrimination, intergroup threat, intergroup contact, child mental health, child behavior checklist

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 20 years, societies around the world have become more ethnically diverse and economically unequal, which has contributed to greater social discord and heightened intergroup threat (Craig et al., 2018; Oxendine, 2019). Intergroup threat is a psychological phenomenon in which individuals perceive people outside of their social group as hostile to their physical or emotional well-being (Stephan, 2014). At the individual level, a strong predictor of elevated threat is negative intergroup contact (Stephan et al., 2002). Negative intergroup contact is highly stressful and can lead individuals to experience a sense of ongoing hypervigilance towards those outside of their social group (Page-Gould et al., 2014; Paradies et al., 2008). Previous findings indicate that parent experiences of psychosocial stress can exert negative impacts on children’s psychological well-being (Lang & Gartstein, 2018), but no work has investigated whether exposures related to intergroup threat (i.e., negative intergroup contact) confer similar risks. Our study examines whether maternal-reported negative intergroup contact is related to poorer mental health in children over a six-year period in early to middle childhood.

Previous work on intergroup threat disproportionately focuses on socially advantaged groups’ attitudes towards marginalized groups (Riek et al., 2006), but numerous studies have also identified heightened threat perceptions among individuals from marginalized groups towards those who are more socially advantaged (Corenblum & Stephan, 2001; Stephan et al., 2002; Vedder et al., 2016). The integrated threat theory provides a useful framework to understand how threat manifests across diverse segments of the population, regardless of social status (Stephan & Stephan, 2017). According to the theory, an intergroup threat can take four different forms: (1) a feeling that the political or economic power, health, or well-being of one’s social group is in danger; (2) a feeling that the morals or values endorsed by one’s social group are under attack; (3) a sense of anxiety about being rejected or ridiculed based on one’s social identity; and (4) holding negative stereotypes towards individuals outside of one’s social group. Evidence shows that these different manifestations of threat are prevalent at comparable levels among lower and higher status groups, ultimately contributing to feelings of mutual distrust (Corenblum & Stephan, 2001; Stephan et al., 2002; Vedder et al., 2016).

To date, most work on intergroup threat has sought to understand how it contributes to prejudice in society (Riek et al., 2006), with little consideration of its broader effects on population mental health. Experiencing a threat based on one’s social identity can elicit negative emotions, including hypervigilance (Page-Gould et al., 2014; Paradies et al., 2008) and a sense of collective angst (Wohl & Branscombe, 2008), which may contribute to elevated levels of psychological distress. Although no epidemiologic studies have investigated the psychological impact of intergroup threat on children, studies of threat-related factors like negative intergroup contact (i.e., being harassed, abused, or discriminated against by members of other social groups) (Stephan et al., 2002; Stephan & Stephan, 2017), provide evidence of potential associations. Discrimination is a form of negative intergroup contact that has been studied extensively in relation to children’s mental health (Anderson et al., 2015; Becares et al., 2015; Cave et al., 2020; Ford et al., 2013; Heard-Garris et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2013; Tran, 2014). A recent longitudinal study of over 1,600 youth of color in the United Kingdom found that higher levels of discrimination reported by mothers when children were 5 years old were associated with greater psychosocial difficulties among these children at age 11 years (Becares et al., 2015). There is also evidence that white parents’ experiences of discrimination can contribute to poorer mental health outcomes in their children, despite the relatively low levels of exposure reported in white populations (Tran, 2014).

Although studies of discrimination provide some evidence of negative intergroup contact’s potential impact on children, they also raise critical questions. First, discrimination is a common experience among marginalized, low social status groups, but is less frequently encountered by non-marginalized, higher status groups. To study the population impact of negative intergroup contact more comprehensively, it is necessary to also consider other exposures that may have broader salience among both high and low social status individuals. Feeling rejected or denigrated by those outside of one’s social group is a psychological form of negative intergroup contact that may also offer important insight (Stephan et al., 2000). Yet, it is worth noting that these attitudes likely manifest differently depending on the relative power one’s social group holds in society (Quillian, 1995; Stephan et al., 2002). For example, the social conditions that contribute to a person of color’s feelings of rejection by white individuals are quite different from those that shape a white individual’s feelings of rejection by people of color. However, even if these circumstances vary by social group, the experience of negative intergroup contact itself is believed to be inherently stressful (Hayward et al., 2017), making these exposures particularly informative for the study of intergroup threat-related impacts on children from socially diverse backgrounds.

In this study, we sought to examine the longitudinal relationship between maternal-reported negative intergroup contact during pregnancy and children’s mental health in a multiethnic sample of children enrolled in the Generation R Study in the Netherlands, where there is both a high prevalence of intergroup threat (Vedder et al., 2016) and striking ethnic disparities in child mental health (Flink et al., 2012). Following prior work on discrimination (Anderson et al., 2015; Becares et al., 2015; Cave et al., 2020; Ford et al., 2013; Heard-Garris et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2013; Tran, 2014), we hypothesized that high levels of negative intergroup contact would predict worse mental health among marginalized, racial/ethnic minority (i.e., non-Dutch) children. On the other hand, we expected that negative intergroup contact would have less of an impact on non-marginalized Dutch children, given their lower levels of exposure and privileged status as members of the dominant racial/ethnic group. To ensure our assessment of negative intergroup contact was relevant to both Dutch and non-Dutch populations, we measured it with respect to two domains: experiences of ethnic discrimination and perceiving hostility from members of other social groups (perceived out-group hostility). All associations were examined stratified by ethnic majority status to account for the different conditions that likely shape experiences of negative intergroup contact among Dutch and non-Dutch mothers. In line with past research, child mental health was indexed by maternal reports of child problem behaviors (Ivanova et al., 2010). To mitigate reporter bias, we adjusted for maternal depressive symptoms at the time negative intergroup contact was assessed, and also examined associations concerning ratings of child behavior provided by other informants. To our knowledge, this population-based study is the first to investigate the mental health impact of exposures related to intergroup threat.

METHODS

Sample

Participants are from the Generation R Study, a Dutch birth cohort (Kooijman et al., 2016). From April 2002 to January 2006, 9,778 pregnant women in Rotterdam were recruited into the study (61% participation rate) (Hofman et al., 2004). Data on their children were collected through questionnaires administered in fetal life through mid-childhood to primary caregivers (primarily mothers), their partners (primarily fathers), and teachers. Questionnaires were available in Dutch, Turkish, and Arabic. Generation R was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, and written informed parental consent was obtained from all participants.

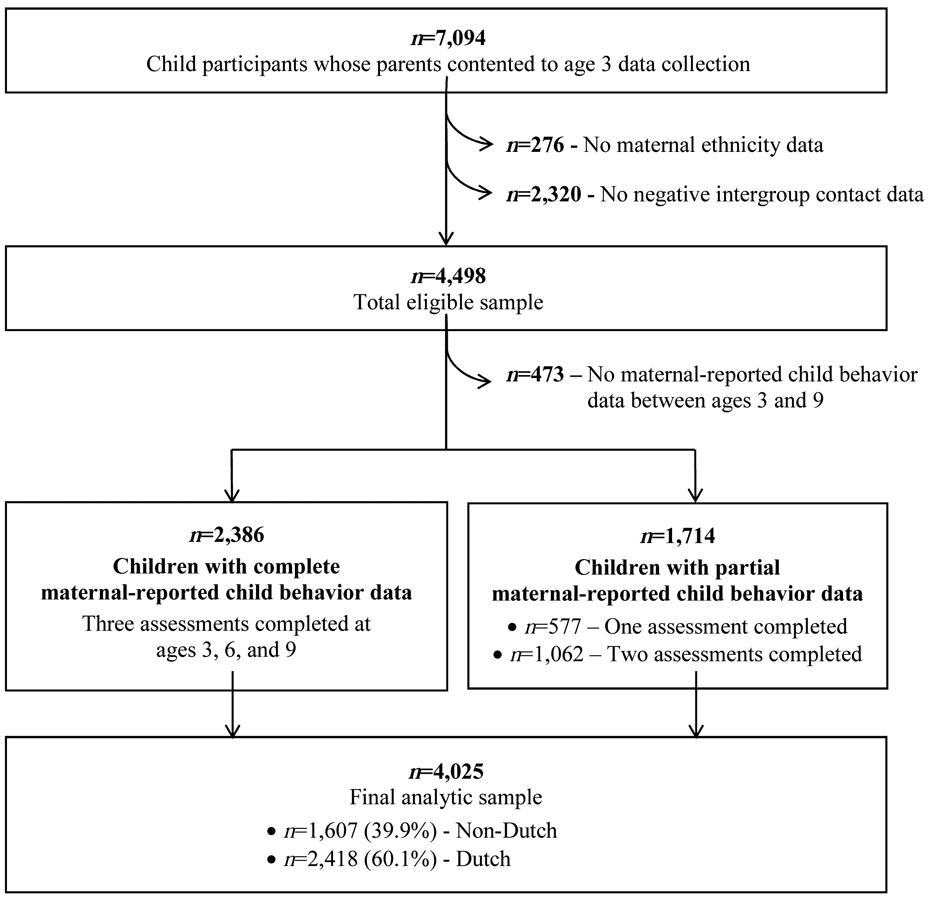

Figure 1 depicts the sample composition over the study period. At age 3, parents of 7,094 children provided consent for their child’s continued participation. Among this group, 276 children who did not have maternal ethnicity data recorded and 2,320 additional children whose mothers did not respond to any negative intergroup contact survey items during pregnancy were considered ineligible. Compared to mothers who responded to ≥1 negative intergroup contact item, those with incomplete data were more likely to be non-Dutch and were more socially disadvantaged. From the total eligible sample of 4,498 participants, children missing behavioral data at all assessments were excluded (n=473, 10.5% lost to follow-up), resulting in an analytic sample of 4,025 children. In the final analytic sample, only missing negative intergroup contact items and covariate data were multiply imputed.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of Generation R participants included in the final analytic sample.

Participant Non-Response and Missing Data Analyses

Our eligible sample excluded the mothers of roughly one-third of participants (n=2,320) who did not respond to any survey items on negative intergroup contact. Compared to mothers who responded to at least one negative intergroup contact item (n=4,498), those with incomplete data were more likely to be non-Dutch (46.3% vs. 43.2%; p=0.02), to have a secondary school or lower level of education (55.4% vs. 45.8%; p<0.001), to report a monthly family income less than €2,000 (25.7% vs. 22.3%; p=0.08), and to be over the age of 35 years at the time of their child’s birth (23.7% vs. 20.2%; p=0.001). They were also more likely to be a first-generation Dutch citizen, and less likely to speak Dutch as their native language. Notably, maternal depression during pregnancy was not associated with non-response.

Although our final analytic sample excluded participants who were missing data on all four negative intergroup contact items, 465 mothers (11.6%) had incomplete data on less than four items. Maternal non-response to individual negative intergroup contact items was not significantly associated with child behavior at follow-up assessments. Yet, when compared to those with complete responses, mothers who did not complete all negative intergroup contact items were more likely to be Dutch (87.1% vs. 56.5%, p<0.001), report a monthly family income more than €4,000 (34.4% vs. 30.9%, p=0.002) and be over 35 years of age at the time of the child’s birth (26.5% vs. 21.3%; p=0.01). Mothers with partial negative intergroup contact data were also less likely to experience depression during pregnancy (4.3% vs. 7.9%, p=0.01), less likely to be a first-generation Dutch citizen, and more likely to speak Dutch as their native language compared to those with complete data.

Among participants in the analytic sample, missing data on individual study covariates ranged from 0% to 28.4%, with family income and maternal native language measures having the highest proportion of missingness (28.4% and 12.5%, respectively). Concerning child problem behavior data, 59.3% of the final analytic sample had measurements available at all three assessments, 26.4% had data from two assessments, and 14.3% had data from only one assessment. In the final analytic sample, only missing negative intergroup contact items and covariate data were multiply imputed.

Measures

Child Mental Health.

Mothers reported child problem behaviors at ages 3, 5, and 9 years using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 2000). A 99-item instrument was administered at ages 3 years (n=3,373; α=0.93) and 5 years (n=3,580; α=0.94), and a 118-item instrument at age 9 years (n=2,906; α=0.94). To examine changes in child problem behavior over time using different versions of the CBCL, scores were transformed onto a common scale (range=0-100) with higher values denoting more problem behavior. Problem behaviors were also assessed via questionnaires completed by fathers at age 9 years (n=2,221; α=0.89) and teachers at age 7 years (n=2,222; α=0.96). For those who were missing ≥25% of CBCL items, scores were weighted to account for missingness. To allow for the estimation of standardized coefficients that could be compared across stratified models, all behavior scores (mother, father, teacher) were standardized within ethnic groups.

Negative Intergroup Contact.

In the third trimester of pregnancy, mothers reported their experiences living in a multicultural society. Negative intergroup contact was assessed using a 4-item measure addressing two types of contact: experiences of ethnic discrimination (“I have been taunted or insulted due to my ethnic background,” “I have been threatened or attacked due to my ethnic background”) and perceived out-group hostility (“I do not feel accepted by [Dutch people/people of other ethnic groups],” “I feel that [Dutch people/people of other ethnic groups] have something against me”). Separate threat measures were constructed for non-Dutch and Dutch participants (see Supplemental Table S1). For each group, overall scores (range=0-16) were derived by summing mothers’ responses across all 4 items, with higher values indicating higher levels of negative intergroup contact. Continuous scores were standardized within ethnic groups and used as the main exposure in all analyses. A 3-category measure was also created to differentiate mothers who experienced no negative intergroup contact (0) from those who reported low (1-4) or high levels (≥5). For sensitivity analyses, subscale measures of ethnic discrimination and perceived out-group hostility were constructed by summing mothers’ ratings on the two items corresponding to each domain, then standardizing within ethnic groups.

Our measure of negative intergroup contact had adequate internal consistency in this sample (αnon-Dutch=0.77, αDutch=0.75). Construct validity was assessed by exploratory factor analysis using iterated principal axis factoring (Hendrickson & White, 1964). Results confirmed that the instrument adhered to a one-factor structure, which accounted for 79.7% of the variance in responses among non-Dutch mothers, and 70.9% of the variance among Dutch mothers (Eigenvaluenon-Dutch=2.0; EigenvalueDutch=2.1). Convergent validity was tested by examining differences in reports of negative intergroup contact by mothers’ social network composition since lower levels are commonly reported in ethnically diverse social networks (ten Berge et al., 2017). During pregnancy, mothers were asked how many people with whom they spent leisure time were Dutch or from other ethnic groups. As expected, participants who spent leisure time with many versus no ethnic out-group friends had lower negative intergroup contact scores (Non-Dutch mean: 1.2 vs. 3.5, p<0.001; Dutch mean: 1.9 vs. 3.1, p=0.1). Divergent validity was assessed by testing associations between maternal reports of negative intergroup contact and the likelihood of having a female child, and no significant trends were observed.

Covariates.

Data were collected through maternal questionnaires administered during pregnancy and when the participating child was 3 years old. Sociodemographic covariates included the child’s sex, advanced maternal age at the child’s birth (≥35 years), low maternal education reported during pregnancy (primary or secondary school, lower vocational/higher vocational and university), and monthly family income reported at age 3 years (<€2,000, €2,000-€3,999, ≥€4,000). Additional maternal covariates included ethnicity defined as mothers’ self-reported country of birth (Dutch, Caribbean, Middle Eastern, African, Asian, other European, or other), native language (Dutch/non-Dutch), and Dutch citizenship (first generation Dutch/second generation Dutch or later). At mid-pregnancy, maternal depression was assessed using a 6-item subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (De Beurs, 2004; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Following the BSI manual, responses were summed then divided by participants’ total endorsed symptoms (range=0-4). Mothers were classified as experiencing depression (yes/no) if they scored above the clinical threshold of 0.80 (De Beurs, 2004).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated in observed data. Differences in mean negative intergroup contact scores by study covariates were evaluated using linear regression in multiply imputed data, while differences in the proportion of mothers who ever experienced negative contact by covariates were assessed using logistic regression.

Associations between maternal-reported negative intergroup contact and repeated child behavior assessments were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with random intercepts and a first-order autoregressive variance-covariance structure (Laird & Ware, 1982; Littell et al., 2000). First, within-individual changes in raw problem behavior scores were examined both overall and by ethnic minority status. Next, standardized associations between maternal-reported negative intergroup contact and child problem behavior averaged over the follow-up period were evaluated separately among non-Dutch and Dutch children. Minimally adjusted models controlled for sex and ethnicity, and fully adjusted models controlled for all study covariates. We then added an interaction between threat and time to fully adjusted models to determine whether negative intergroup contact was related to children’s yearly rate of change in problem behavior. Continuous standardized negative intergroup contact scores were the primary exposure in all analyses however relationships were also assessed with discrete levels of negative intergroup contact (none, low, high) to identify potentially discontinuous associations. Domain-specific measures of negative intergroup contact were also examined as separate exposures to determine whether observed relationships might be driven more strongly by ethnic discrimination or perceived out-group hostility.

To mitigate reporter bias, we also assessed negative intergroup contact regarding child problem behavior rated by different informants. Since repeated measures were not available from all informants, linear regression models compared associations between negative intergroup contact and standardized child problem behavior rated by participants’ mothers at age 9 years, fathers at age 9 years, and teachers at age 7 years. All analyses were conducted in Stata MP v.15.1.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The composition of the sample was ethnically diverse, with 39.9% of mothers reporting a non-Dutch ethnicity (25.9% Middle Eastern, 22.3% Caribbean, 21.8% other European). Table 1 describes the non-Dutch and Dutch subsamples. Among non-Dutch participants, 59.7% had a mother who received a secondary school level education or lower (vs. 30.3% of Dutch), 39.4% reported a monthly family income ≤€2,000 (vs. 12.5% of Dutch), and 12.5% had mothers who met criteria for depression during pregnancy (vs. 4.2% of Dutch). Only one-third of ethnic minority mothers reported speaking Dutch as their native language, and nearly two-thirds were first-generation citizens of the Netherlands.

Table 1.

Distribution of maternal-reported negative intergroup contact level by study covariates, stratified by ethnic minority status.a

| Negative Intergroup Contact |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Dutch (N=1,607) |

Dutch (N=2,418) |

|||||

| n (Percent) | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | n (Percent) | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Mother’s Ethnicity | ||||||

| Dutch | 2,418 (100.0) | 2.79 (2.7, 2.9) | -- | |||

| Caribbean | 358 (22.3) | 2.71 (2.4, 3.1) | -- | |||

| Middle Eastern | 416 (25.9) | 3.50 (3.2, 3.8) | 0.001 | |||

| African | 164 (10.2) | 2.48 (2.0, 3.0) | 0.4 | |||

| Asian | 251 (15.6) | 1.99 (1.6, 2.4) | 0.006 | |||

| Other European | 351 (21.8) | 1.46 (1.2, 1.7) | <0.001 | |||

| Other | 67 (4.2) | 1.55 (0.8, 2.3) | 0.006 | |||

| Child’s Gender | ||||||

| Female | 817 (50.8) | 2.49 (2.3, 2.7) | 0.7 | 1,183 (48.9) | 2.8 (2.6, 3.0) 0.7 | |

| Male | 790 (49.2) | 2.42 (2.2, 2.7) | 1,235 (51.1) | 2.8 (2.6, 2.9) | ||

| Advanced Maternal Age at Child’s Birth | ||||||

| 35 Years or Older | 296 (18.4) | 2.11 (1.8, 2.5) | 0.04 | 586 (24.2) | 2.8 (2.5, 3.0) | 0.8 |

| Younger than 35 Years | 1,311 (81.6) | 2.54 (2.4, 2.7) | 1,832 (75.8) | 2.8 (2.7, 2.9) | ||

| Maternal Education | ||||||

| Low | 935 (59.7) | 3.86 (3.3, 4.4) | <0.001 | 730 (30.3) | 4.2 (3.7, 4.7) | <0.001 |

| High | 632 (40.3) | 2.90 (2.0, 3.8) | 1,677 (69.7) | 3.4 (2.6, 4.2) | ||

| Monthly Family Income at 3y | ||||||

| ≥ €4,000 | 455 (39.4) | 3.37 (3.1, 3.6) | -- | 257 (12.5) | 3.5 (3.2, 3.9) | -- |

| €2,000-€3,999 | 497 (43.1) | 2.11 (1.5, 2.8) | <0.001 | 1,012 (49.1) | 2.9 (2.1, 3.6) | 0.002 |

| < €2,000 | 202 (17.5) | 1.15 (0.4, 1.3) | <0.001 | 793 (38.5) | 2.5 (1.7, 3.3) | <0.001 |

| Maternal Depression in Pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 1,221 (87.5) | 2.78 (2.1, 2.5) | <0.001 | 2,098 (95.8) | 2.7 (2.6, 2.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 175 (12.5) | 3.67 (3.0, 4.3) | 93 (4.2) | 4.1 (3.3, 4.8) | ||

| Mother’s Dutch Citizenship History | ||||||

| Second Generation Citizen or Later | 568 (36.5) | 1.89 (1.6, 2.2) | <0.001 | 2,358 (98.2) | 2.8 (2.7, 2.9) | 0.3 |

| First Generation Citizen | 989 (63.5) | 2.79 (2.2, 3.4) | 44 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.3, 3.3) | ||

| Mother’s Native Language | ||||||

| Non-Dutch | 875 (66.4) | 2.9 (2.7, 3.1) | <0.001 | 5 (0.2) | 2.8 (−0.7, 6.3) | 0.7 |

| Dutch | 442 (33.6) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.2) | 2,187 (99.8) | 2.5 (0.7, 4.3) | ||

ns are based on observed values and may vary due to missing data.

Mean negative intergroup contact levels and 95% CIs were calculated in multiple imputed data. p-values indicate unadjusted differences in negative intergroup contact levels by study covariates among non-Dutch and Dutch participants.

Correlates of Negative Intergroup Contact

Mean negative intergroup contact levels by study covariates are provided in Table 1. Middle Eastern mothers reported experiencing the highest levels of negative intergroup contact, followed by Dutch and Caribbean mothers. When ethnic groups were combined to examine mean levels of contact by ethnic minority status, a larger proportion of Dutch mothers indicated experiencing any negative contact (66.6%) compared to non-Dutch (52.3%; p<0.001). For non-Dutch mothers, younger age, speaking a non-Dutch native language, and being a first-generation Dutch citizen predicted higher levels of negative intergroup contact, while low levels of education and income, and experiencing depression during pregnancy were associated with higher levels of exposure in both groups.

When negative intergroup contact was disaggregated into ethnic discrimination and perceived out-group hostility, a somewhat different picture emerged. A greater proportion of non-Dutch mothers (29%) reported experiencing discrimination compared to Dutch mothers (13.6%; p<0.001), while more Dutch mothers (66.0%) reported perceiving out-group hostility compared to non-Dutch mothers (45.2%; p<0.001). Social disadvantage also predicted higher levels of ethnic discrimination and perceived hostility among both groups, mirroring trends with overall levels of negative intergroup contact.

Longitudinal Associations Between Negative Intergroup Contact and Child Mental Health

Among all children, problem behavior significantly declined over time after adjusting for age at baseline, sex, and ethnicity (bper year=−0.53, 95% CI=−0.57, −0.48). After stratifying by ethnic minority status, problem behavior decreased at a faster rate for non-Dutch (bper year=−0.87, 95% CI=−0.96, −0.78) compared to Dutch children (bper year=−0.35, 95% CI=−0.40, −0.31; Pinteraction<0.001).

For all children, regardless of ethnic minority status, higher levels of maternal-reported negative intergroup contact were associated with more problem behavior at every time point over the follow-up period (Figure 2). Adjusting for age at baseline, sex, and ethnicity, each standard deviation (SD) increase in negative intergroup contact was associated with a 0.12-0.14-SD higher problem behavior score averaged across the follow-up period (Bnon-Dutch=0.12, 95% CI=0.08, 0.16; BDutch=0.14, 95% CI=0.11, 0.18). Among non-Dutch participants, associations varied in magnitude by ethnicity, with the strongest relationships observed among Asian (B=0.25, 95% CI=0.14, 0.36) and African children (B=0.17, 95% CI=0.03, 0.31), and the weakest among Middle Eastern children (B=0.07, 95% CI=−0.02, 0.15). Formal tests for interactions did not find evidence of substantial differences between groups. Overall associations were only slightly attenuated after adjusting for all study covariates (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Raw child emotional and behavioral problem scores over the follow-up period by levels of maternal-reported negative intergroup contact among non-Dutch (N=700) and Dutch (N=1,383) participants.a

a Sample sizes based on participants with available child behavior problem data at all follow-up points and complete data on negative intergroup contact.

Table 2.

Fully adjusted, standardized associations between levels of maternal-reported negative intergroup contact and child problem behavior scores averaged across the follow-up period, stratified by ethnic minority status.a, b

| Child Problem Behaviors, Per 1-SD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Dutch (N=1,607) |

Dutch (N=2,418) |

|||

| B (95% CI) | p-value | B (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Negative Intergroup Contact, Per 1-SD | 0.10 (0.05, 0.14) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.08, 0.15) | <0.001 |

| Time | −0.00 (0.02, 0.01) | 0.38 | 0.002 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.57 |

Child problem behavior scores were standardized within ethnic groups at each time point over the follow-up period. Effect estimates should be interpreted as the standard deviation (SD) difference in CBCL scores across childhood associated with standard deviation higher exposure to negative intergroup contact.

Fully adjusted model controlled for child’s age at baseline, sex, maternal ethnicity, advanced maternal age at child’s birt maternal education, family income at age 3, mother’s Dutch citizenship history, and mother’s native language.

Associations between categorical levels of negative intergroup contact and standardized problem behaviors are provided in Supplemental Table S2. For both Non-Dutch and Dutch children, compared to those whose mothers reported no exposure, those whose mothers reported high levels of negative intergroup contact experienced roughly a quarter-SD more problem behaviors across childhood. To put the magnitude of this relationship into perspective, the effect estimates for high levels of exposure were comparable to the impact of having a low versus high family income (e.g., non-Dutch bhigh threat=0.24 vs. blow income=0.26; Dutch bhigh threat=0.26 vs. blow income=0.17). Notably, even low levels of exposure were associated with more problem behaviors for both groups of children (non-Dutch blow threat=0.19, 95% CI=0.085, 0.30; Dutch blow threat=0.17, 95% CI=0.082, 0.26).

Negative intergroup contact was not related to children’s rate of decline in problem behavior among non-Dutch participants, but an association was observed among Dutch children (ptime interaction=0.06). Those whose mothers reported no exposure (b=−0.40, 95% CI=−0.48, −0.32) experienced a faster decline in problem behaviors than those whose mothers reported low (b=−0.37, 95% CI=−0.46, −0.28) and high levels (b=−0.31, 95% CI=−0.41, −0.22).

Associations of Ethnic Discrimination and Perceived Out-Group Hostility with Child Mental Health

Results from fully adjusted analyses considering longitudinal associations with ethnic discrimination and perceived out-group hostility separately are provided in Table 3. Both forms of negative intergroup contact were associated with more problem behavior averaged across childhood for all children, regardless of ethnic minority status. Among non-Dutch participants, the fully adjusted association between problem behavior and maternal-reported discrimination (B=0.10, 95% CI=0.06, 0.14) was comparable to that with perceived out-group hostility (B=0.06, 95% CI=0.01, 0.11). In contrast, for Dutch participants, the relationship of child behavior with ethnic discrimination was weak (B=0.01, 95% CI=0.01, 0.02), but more substantial and in the expected direction with perceived hostility (B=0.11, 95% CI=0.08, 0.15).

Table 3.

Fully adjusted, standardized associations between (a) maternal-reported ethnic discrimination, and (b) perceived out-group hostility, respectively, and child problem behavior scores averaged across the follow-up period, stratified by ethnic minority status.a, b

| Child Problem Behaviors, Per 1-SD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Dutch (N=1,607) |

Dutch (N=2,418) |

|||

| B (95% CI) | p-value | B (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Ethnic Discrimination, Per 1-SD | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14) | <0.001 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | <0.001 |

| Time | −0.00 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.37 | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.58 |

| Perceived Out-Group Hostility, Per 1-SD | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.01 | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) | <0.001 |

| Time | −0.00 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.38 | 0.00 (0.08, 0.15) | 0.57 |

Child problem behavior scores were standardized within ethnic groups at each time point over the follow-up period. Effect estimates should be interpreted as the standard deviation (SD) difference in CBCL scores across childhood associated with standard deviation higher exposure to each form of negative intergroup contact.

Fully adjusted model controlled for child’s age at baseline, sex, maternal ethnicity, advanced maternal age at child’s birth, maternal education, family income at age 3, mother’s Dutch citizenship history, and mother’s native language.

Prospective Analyses Across Multiple Informants

Results from analyses using child behavior data from different informants are reported in Supplemental Table S3. Among non-Dutch participants, a significant association between negative intergroup contact and child problem behavior was observed only with maternal-reported behavior, but associations with paternal- and teacher-rated behavior were evident and in the expected directions. Among Dutch participants, significant associations were observed with both maternal-reported and teacher-reported problem behaviors, and the association with paternal-rated problem behaviors was also evident in the same direction.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have identified factors in children’s immediate social environments that confer elevated psychiatric risk (Yap et al., 2014), but less research has examined exposures related to intergroup threat, like negative intergroup contact. In a diverse, community-based sample, we found that higher levels of negative intergroup contact reported by mothers during pregnancy were associated with poorer child mental health over a 6-year period. Moreover, findings were independent of mothers’ psychological distress at the time negative intergroup contact was assessed and were largely confirmed using evaluations of child behavior from other informants. Although the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain poorly understood, research on discrimination indicates that the stress of such experiences may impair parents’ mental health and parenting practices, which can leave lasting effects on youth (Becares et al., 2015; McNeil et al., 2014; Tran, 2014).

Although we hypothesized that exposure to negative intergroup contact would be less impactful for Dutch children due to their lower levels of exposure as members of a non-marginalized group, our results showed remarkably comparable associations among both Dutch and non-Dutch participants (see Figure 2 and Table 2). Prior work documenting the negative mental health effects of discrimination among white adults may help contextualize this unexpected finding (Malat et al., 2018). Some researchers hypothesize that since white (i.e., racial/ethnic majority) populations are infrequently targeted based on their social identity, poor outcomes may be attributable to insufficient coping resources to handle threats to their social standing (Kessler, 1979; Malat et al., 2018). It is important to recognize, however, that the negative intergroup contact reported by Dutch and non-Dutch mothers in our study are unlikely to be shaped by similar social conditions. Research in social psychology finds that intergroup threat exposure among people of color is largely driven by their experiences of poor treatment in society as well as negative public sentiment directed towards racial/ethnic minority groups (Stephan et al., 2002). On the other hand, perceptions of threat among white individuals are often psychologically based, deriving from normative prejudicial attitudes towards minorities (Quillian, 1995). Regardless, our findings may suggest that negative intergroup contact confers similar risks on mental health for both Dutch and non-Dutch children because it is inherently stressful, irrespective of the different social circumstances in which it occurs.

While we were unable to test this directly in our study, it is supported by trends we observed with ethnic discrimination and perceived out-group hostility, respectively. In our main analyses, an overall exposure measure was created by equally weighting both forms of negative intergroup contact, yet, when each was examined separately, findings indicated that associations may depend on their respective salience to each group (see Table 3). Ethnic discrimination reflects lived experiences of negative intergroup contact and therefore may be a more relevant measure among marginalized groups. Indeed, this was affirmed in our sample, as discrimination was more commonly reported by non-Dutch than Dutch mothers, and also appeared to have a more substantial impact on non-Dutch children. On the other hand, perceived out-group hostility reflects a psychological dimension of negative intergroup contact that may be more meaningful to non-marginalized groups. Again, this was confirmed in our sample, as Dutch mothers reported higher levels of perceived hostility compared to non-Dutch mothers, and its impact on the mental health of Dutch children also appeared to be more sizable than that among non-Dutch children. Notably, these findings reflect broader trends in the Netherlands, where ethnic discrimination is frequently experienced by citizens of non-Dutch ethnicities and negative attitudes towards racial/ethnic minorities are widespread (Gonzalez et al., 2008; Savelkoul et al., 2012).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has some limitations. Maternal perceptions of negative intergroup contact reported in childhood may be more predictive of behavior problems than those reported during pregnancy. Since negative intergroup contact was only assessed once in Generation R, we were unable to examine changes over time; still, we expect that associations with more proximal assessments may be stronger than what we observed. Data availability also precluded us from examining whether the impact of negative intergroup contact is distinct from maternal stress more generally. Although associations were robust to adjustment for maternal psychological distress, future work should assess exposures related to intergroup threat while accounting for other forms of psychosocial stress. Another limitation relates to participant non-response. Mothers who were included in our final sample differed from those who were excluded on important covariates, namely they were more likely to be Dutch and were more socially advantaged. As a result, non-Dutch mothers in our study may represent a somewhat resilient sub-sample, limiting generalizability and perhaps making our findings a somewhat conservative estimate of the impact of negative intergroup contact on non-Dutch children. Lastly, maternal ethnicity was assessed via mothers’ self-reported country of birth and therefore may have been susceptible to misclassification among Dutch citizens of non-Dutch ethnicities. Although we were unable to address this directly, fully adjusted analyses accounted for Dutch citizenship history and maternal native language in both subsamples.

This study also has numerous strengths. By expanding our focus beyond discrimination to also consider a psychological form of negative intergroup contact (perceived out-group hostility), we captured intergroup threat-related exposures that are as relevant to non-marginalized populations as they are to those who are more marginalized. Furthermore, we examined associations separately among Dutch and non-Dutch children to account for differences in the social conditions that may influence mothers’ exposure to negative intergroup contact within each group. Although this prevented us from formally testing for differences in the strength of associations between these groups, we were able to examine effect modification by ethnic subgroups among those from non-Dutch backgrounds. Relatedly, our study was conducted in a large, multi-ethnic cohort, which included a sizeable number of ethnic minority participants, providing sufficient statistical power to identify potential differences between these groups.

To our knowledge, this epidemiologic study is the first to examine the impact of exposures related to intergroup threat on children’s mental health. Notably, we found that both high and low levels of maternal-reported negative intergroup contact were associated with more problem behaviors among both ethnic minority and majority youth, suggesting that risk may be conferred even when parental exposure is less severe. From a public health perspective, this suggests that even small shifts in negative intergroup contact at the population level may lead to improvements in children’s mental health. Prior work finds that positive contact may reduce perceptions of threat (Christ et al., 2014), which in turn might reduce child problem behavior in the population if encouraged through widespread policy or program initiatives. Among youth, positive contact can be promoted through diverse friendship networks, which may help mitigate intergroup threat-related exposures over time, particularly as young people form social relationships outside of the home (Davies et al., 2011). Future research should examine the mental health impact of socially inclusive policies that facilitate positive contact between diverse groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Intergroup threat is a widespread psychological phenomenon with particular relevance to the present sociopolitical climate of many diverse societies around the globe. Although well-documented in the social psychology literature, research exploring its potential health impacts is scarce. Our findings serve as proof of the principle that intergroup threat-related exposures may be informative for children’s psychological well-being, warranting further study regarding other health outcomes across the life course.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Studied mother-child pairs in the Generation R Study, a multi-ethnic Dutch birth cohort.

Maternal-reported negative intergroup contact predicted poorer child mental health.

Associations were comparable among marginalized and non-marginalized groups.

Results suggest negative contact may exert population-wide effects on mental health.

Acknowledgements:

The Generation R Study is conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center in close collaboration with the Erasmus University Rotterdam, School of Law and Faculty of Social Sciences, the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, the Rotterdam Homecare Foundation, and the Stichting Trombosedienst and Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond (STAR). The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of general practitioners, hospitals, midwives, and pharmacies in Rotterdam.

Financial support for the Generation R Study comes from the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Erasmus University Rotterdam, and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). This research was conducted by the authors. Dr. Qureshi was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 098048 and T32 CA 009001 at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youths & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Hussain SB, Wilson MN, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, & Williams JL (2015). Pathways to pain: Racial discrimination and relations between parental functioning and child psychosocial well-being. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 491–512. DOI: 10.1177/0095798414548511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, & Leaf PJ (2011). Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20, 40–49. DOI: 10.1002/mpr.329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becares L, Nazroo J, & Kelly Y (2015). A longitudinal examination of maternal, family, and area-level experiences of racism on children's socioemotional development: Patterns and possible explanations. Social Science & Medicine, 142, 128–135. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave L, Cooper MN, Zubrick SR, Shepherd CCJ (2020). Racial discrimination and child and adolescent health in longitudinal studies: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 250, 112864. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ O, Schmid K, Lolliot S, Swart H, Stolle D, Tausch N, et al. (2014). Contextual effect of positive intergroup contact on outgroup prejudice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 3996–4000. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1320901111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corenblum B, & Stephan WG (2001). White fears and native apprehensions: An integrated threat theory approach to intergroup attitudes. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 33, 251. DOI: 10.1037/h0087147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig MA, Rucker JM, & Richeson JA (2018). The pitfalls and promise of increasing racial diversity: Threat, contact, and race relations in the 21st century. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 188–193. DOI: 10.1177/0963721417727860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K, Tropp LR, Aron A, Pettigrew TF, & Wright SC (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 332–351. DOI: 10.1177/1088868311411103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Melisaratos N (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beurs E (2004). Brief Symptom Inventory, Handleiding (Manual).

- Flink IJ, Jansen PW, Beirens TM, Tiemeier H, van IMH, Jaddoe VW, et al. (2012). Differences in problem behaviour among ethnic minority and majority preschoolers in the Netherlands and the role of family functioning and parenting factors as mediators: The Generation R Study. BMC Public Health, 12, 1092. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Hurd NM, Jagers RJ, & Sellers RM (2013). Caregiver experiences of discrimination and African American adolescents' psychological health over time. Child Development, 84, 485–499. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01864.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez KV, Verkuyten M, Weesie J, & Poppe E (2008). Prejudice towards Muslims in The Netherlands: Testing integrated threat theory. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 667–685. DOI: 10.1348/014466608X284443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LE, Tropp LR, Hornsey MJ, & Barlow FK (2017). Toward a comprehensive understanding of intergroup contact: Descriptions and mediators of positive and negative contact among majority and minority groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 347–364. DOI: 10.1177/0146167216685291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard-Garris NJ, Cale M, Camaj L, Hamati MC, & Dominguez TP (2018). Transmitting Trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 230–240. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson AE, & White PO (1964). Promax: A quick method for rotation to oblique simple structure. British Journal of Statistical Psychology, 17, 65–70. DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1964.tb00244.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman A, Jaddoe VWV, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Snijders RFM, Steegers EAP, et al. (2004). Growth, development and health from early fetal life until young adulthood: The Generation R Study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 18, 61–72. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2003.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Harder VS, Ang RP, Bilenberg N, et al. (2010). Preschool psychopathology reported by parents in 23 societies: Testing the seven-syndrome model of the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1.5-5. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 1215–1224. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly Y, Becares L, & Nazroo J (2013). Associations between maternal experiences of racism and early child health and development: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67, 35–41. DOI: 10.1136/jech-2011-200814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (1979). Stress, social status, and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 20, 259–272. DOI: 10.2307/2136450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM, Duijts L, Franco OH, van Ijzendoorn MH, et al. (2016). The Generation R Study: Design and cohort update 2017. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 1243–1264. DOI: 10.1007/s10654-016-0224-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird NM, & Ware JH (1982). Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics, 38, 963–974. DOI: 10.2307/2529876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, & Gartstein MA (2018). Intergenerational transmission of traumatization: Theoretical framework and implications for prevention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19, 162–175. DOI: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1329773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Pendergast J, & Natarajan R (2000). Modelling covariance strucutre in the analysis of repeated measures data. Statistics in Medicine, 19, 1793–1819. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malat J, Mayorga-Gallo S, & Williams DR (2018). The effects of whiteness on the health of whites in the USA. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 148–156. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil S, Harris-McKoy D, Brantley C, Fincham F, & Beach SRH (2014). Middle class African American mothers' depressive symptoms mediate perceived discrimination and reported child externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 381–388. DOI: 10.1007/s10826-013-9788-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxendine AR (2019). The political psychology of inequality and why it matters for populism. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 8, 179. DOI: 10.1037/ipp0000118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page-Gould E, Mendoza-Denton R, & Mendes WB (2014). Stress and coping in interracial contexts: The influence of race-based rejection sensitivity and cross-group friendship in daily experiences of health. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 256–278. DOI: 10.1111/josi.12059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Williams DR, Heggenhougen K, & Quah S (2008). Racism and health. International Encyclopedia of Public Health (2nd ed., pp. 249–259). Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L (1995). Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review, 60, 586–611. DOI: 10.2307/2096296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riek BM, Mania EW, & Gaertner SL (2006). Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 336–353. DOI: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelkoul M, Scheepers P, van der Veld W, & Hagendoorn L (2012). Comparing levels of anti-Muslim attitudes across Western countries. Quality & Quantity, 46, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan CW, Stephan WC, Demitrakis KM, Yamada AM, & Clason DL (2000). Women's attitudes toward men: An Integrated Threat Theory approach. Psychology of women Quarterly, 24, 63–73. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01022.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan WG (2014). Intergroup anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 239–255. DOI: 10.1177/1088868314530518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan WG, Boniecki KA, Ybarra O, Bettencourt A, Ervin KS, Jackson LA, et al. (2002). The role of threats in the racial attitudes of blacks and whites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1242–1254. DOI: 10.1177/01461672022812009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan WG, & Stephan CW (2017). Intergroup threat theory. The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication (pp. 1–12). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- ten Berge JB, Lancee B, & Jaspers E (2017). Can interethnic friends buffer for the prejudice increasing effect of negative interethnic contact? A longitudinal study of adolescents in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 33, 423–435. DOI: 10.1093/esr/jcx045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran A (2014). Family contexts: Parental experiences of discrimination and child mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 37–46. DOI: 10.1007/s10464-013-9607-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedder P, Wenink E, & van Geel M (2016). Explaining negative outgroup attitudes between native Dutch and Muslim youth in The Netherlands using the Integrated Threat Theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 53, 54–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl MJ, & Branscombe NR (2008). Collective angst: How threats to the future vitality of the ingroup shape intergroup emotion. In Wayment HA & Bauer JJ (Eds.), Transcending self-interest: Psychological explorations of the quiet ego (p. 171–181). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, Pilkington PD, Ryan SM, & Jorm AF (2014). Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 156, 8–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.