Abstract

Introduction

The end-of-life symptom prevalence of non-cancer patients have been described mostly in hospital and institutional settings. This study aims to describe the average symptom trajectories among non-cancer patients who are community-dwelling and used home care services at the end of life.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective, population-based cohort study of non-cancer patients who used home care services in the last 6 months of life in Ontario, Canada, between 2007 and 2014. We linked the Resident Assessment Instrument for Home Care (RAI-HC) (standardized home care assessment tool) and the Discharge Abstract Databases (for hospital deaths). Patients were grouped into four non-cancer disease groups: cardiovascular, neurological, respiratory, and renal (not mutually exclusive). Our outcomes were the average prevalence of these outcomes, each week, across the last 6 months of life: uncontrolled moderate-severe pain as per the Pain Scale, presence of shortness of breath, mild-severe cognitive impairment as per the Cognitive Performance Scale, and presence of caregiver distress. We conducted a multivariate logistic regression to identify factors associated with having each outcome respectively, in the last 6 months.

Results

A total of 20,773 non-cancer patient were included in our study, which were analyzed by disease groups: cardiovascular (n = 12,923); neurological (n = 6,935); respiratory (n = 6,357); and renal (n = 3,062). Roughly 80% of patients were > 75 years and half were female. In the last 6 months of life, moderate to severe pain was frequent in the cardiovascular (57.2%), neurological (42.7%), renal (61.0%) and respiratory (58.3%) patients. Patients with renal disease had significantly higher odds for reporting uncontrolled moderate to severe pain (odds ratio [OR] = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.34) than those who did not. Patients with respiratory disease reported significantly higher odds for shortness of breath (5.37; 95% CI, 5.00 to 5.80) versus those who did not. Patients with neurological disease compared to those without were 9.65 times more likely to experience impaired cognitive performance and had 56% higher odds of caregiver distress (OR = 1.56; 95% CI: 1.43 to 1.71).

Discussion

In our cohort of non-cancer patients dying in the community, pain, shortness of breath, impaired cognitive function and caregiver distress are important symptoms to manage near the end of life even in non-institutional settings.

Introduction

Multiple randomized controlled trials, and other clinical trials, have shown that a palliative approach to care is beneficial to improve the dying experience and patient outcomes including improved well-being, symptom management, quality-of-life, satisfaction with care and decreased caregiver distress and Emergency Department visits at the end of life [1–8]. Despite evidence of the benefits of palliative care in non-cancer populations, referrals to palliative care services are more often happening in cancer patients versus non-cancer patients [9–14]. One reason for this might be that unmet symptoms and their symptom trajectories are very well described in the cancer population, as compared to the non-cancer population (e.g., chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, renal disease and Alzheimer’s dementia) where the illness trajectory tends to be much less predictable [15–21].

Research shows that patients with advanced cancer diagnoses compared to non-cancer diagnoses (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, etc.) have similar needs at the end-of life, including needs for emotional well-being, physical functioning and quality of life [22]. However, non-cancer patients often receive palliative care supports later in the illness trajectory. For instance, in retrospective studies of cancer vs. non-cancer patients, non-cancer patients presented with lower functional status when initially referred to palliative care [23, 24]. A systematic review of 15 studies around end-of-life needs of non-cancer patients reported the body of research-to-date as being qualitative and descriptive and suggested more longitudinal and observational studies are necessary to identify patients that would benefit from a palliative care referral in the context of their illness and associated symptom trajectories [16]. Many of these studies were conducted in hospital and institutional settings, and thus population-based symptom prevalence over time, particularly for community-dwelling patients dying at home, has not been well-studied.

To address this gap, our study focuses on a population-based non–cancer cohort in Ontario, Canada who accessed publicly-funded home care services. All individuals using homecare service receive a standardized assessment, specifically the Resident Assessment Instrument for Home Care (RAI-HC). The RAI-HC is completed every six months, providing us with a large sample of diverse patients who are followed over time in the community until death. Our study aimed to describe the average symptom trajectories for a cohort of non-cancer patients in the last six months of life and identify factors associated with having a symptom issue.

Materials and methods

Study design, participants, and setting

This is a retrospective, population-based cohort study of non-cancer patients who accessed publicly-funded home care services in the province of Ontario, Canada between January 1, 2007 to March 31, 2014. To be included, patients had to have a documented death during the study period (either at home or hospital), have used home care (and thus have a home care assessment) in the final six months of life, and a non-cancer diagnosis (as per the home care assessment).

Data sources

We used routinely collected clinical health administrative data. Specifically, our study merged the Resident Assessment Instrument for Home Care (RAI-HC) database for home care and the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) for hospitals at the individual-level through unique health insurance numbers. (See S1 Fig). Individuals expected to receive at least 60 days of home care and receive a standardized assessment tool, called the RAI-HC (akin to the Minimum Data Set in the USA). This assessment tool is mandated by the province for billing, accountability, and research purposes. The RAI-HC is completed in the patient’s home by a trained professional (typically a registered nurse) on a laptop, following a detailed coding manual [25]. Thus, the tool contains provider-reported outcome measures. The assessment is repeated roughly every 6 months, unless there is a major change in health status or a discharge from hospital [26]; thus patients can have multiple assessments completed. The assessor completes the RAI-HC based on an interview with the patient and their family in their homes and using their best clinical judgement. The assessment includes, but is not limited to, items that measure the client’s functional status, psychosocial well-being, physical health, and care needs [27]. There have been multiple studies that attest to the reliability and validity of items within the RAI-HC [25, 28–30]. If a patient dies while receiving home care, date of death is document in the RAI-HC. If a patient dies in hospital, date of death is recorded in the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD).

Variables

Our main variable was non-cancer diagnosis. Patients in the study population were grouped into four non-mutually exclusive diagnostic categories: 1) cardiovascular (cerebrovascular accident, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease); 2) neurological (Alzheimer’s dementia, dementia [other than Alzheimer’s], multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism); 3) respiratory (emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma); and 4) renal failure as indicated on the RAI-HC assessment (item J1a-ac). If a patient had cancer (item J1x), they were excluded from the cohort. Disease groups are not mutually exclusive, since individuals often have multiple co-morbid chronic conditions. To compare patients equally over time, we aligned patients’ date of death as time zero and then counted backwards 26 weeks (approximately 6 months) from death.

Outcomes

All outcomes of interest were derived from the RAI-HC assessment and included pain, shortness of breath (physical symptoms), cognitive performance and caregiver distress (psychosocial symptoms).

Pain: Moderate-severe daily pain that was also uncontrolled was measured by having a score of 2 or higher out of 4 on the Pain Scale (item K4a-b) (meaning the frequency is daily and the intensity is moderate to severe) and that the pain was uncontrolled (item K4e) (i.e., “medications do not adequately control pain”) [31].

Shortness of breath (item K3e): “Shortness of breath was present in the past 3 days” (yes/no)

Cognitive performance: Mild-severe cognitive impairment was measured as a score of 2 or higher out of 6 on the Cognitive Performance scale (CPS) (item B1-2 and C) [32]. The Cognitive Performance scale is a hierarchical screener which includes two items found on traditional cognitive assessments (e.g., short-term memory, daily decision making) and two items reflecting functional status (e.g., expressive communication, independence in eating). The scale ranges from zero to six (0 = no cognitive impairment; 1 = borderline intact; 2 = mild impairment; 3 = moderate impairment; up to 6 = very severe impairment).

Caregiver distress (item G2c): “Patient’s primary informal caregiver experiences feelings of anger, depression or distress” (yes/no).

Covariates

Other dichotomous covariates included: i) caregiver lives with patient (item G1e) (yes/no); ii) death in hospital (yes/no); iii) loss of appetite (item K2d) (yes/no); iv) social decline causing distress (item F2) (yes/no); v) signs and symptoms of depression as measured by the Depression Rating Scale (DRS) [33] score of 3 or more (item E1-4) (yes/no); and vi) moderate-severe impairment as measured by the Activities of Daily living (ADL) Self-performance Hierarchy scale [34] score of 2 or more (item H1-7) (yes/no). These covariates were shown to be associated with the outcomes in prior research [35].

Statistical methods

We used data from all RAI-HC assessments in any patient’s last 26 weeks of life to create the average trajectory of each symptom over time. When describing the demographic and health characteristics of our cohort, only the most recent RAI-HC assessment for each individual was used. The data present the proportion of patients who completed a RAI-HC from 26 weeks until one week (which represented 0–7 days) before death, and who had that symptom/issue present. Multivariate logistic regression models were created to compare the odds of having the outcomes respectively in the final 6 months of life, controlling for age, sex, disease group, and other covariates described above. All results were reported as an adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. As a sensitivity test, we examined the outcomes by those who died in hospital versus died at home separately; this was to explore the potential for selection bias, whereby patients who were more symptomatic would be admitted to hospital before reporting symptoms in the home care assessment. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4. The study was approved and deemed exempt by Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Project #3039) and the Wilfrid Laurier University Research Ethics Board (REB #5310) as it used de-identified secondary data analysis. All necessary permissions and approval to access the data were obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Results

In our study population of home care patients assessed between 2007–2014, the total number of unique individuals that contributed assessments during the last six months of life and fit the study criteria was 37,981. After excluding individuals with a cancer diagnosis from this group, the final sample size of unique individuals was 20,773 (33,596 assessments). Based on non-exclusive diagnosis categories, we had home care patients grouped into cardiovascular (n = 12,923), neurological (n = 6,935), respiratory (n = 6,357) and renal (n = 3,062) diagnoses. Overall, 64% patients died in the hospital. In our cohort, 42.4% had their most recent home care assessment 3 to 6 months before death, 36.9% in the 1–3 months before death, and 20.6% in the final 1 month of life.

Most of the patients were over the age of 75 years old (ranging from 81.2% in the circulatory, 87.8% in the neurological, 74.2% in the respiratory and 72.8% in the renal group). Half of the population were female. Approximately 60% of patients lived with a primary caregiver (Table 1). One-fifth of patients showed signs and symptoms of depression across the four disease groups. Moderate to severe impairment in completing Activities of Daily Living were highest in the neurological group (50.2%) compared to 31.0% in the circulatory, 23.4% in the respiratory, and 29.7% in the renal group. Social decline that caused distress was found in approximately 15% of patients in the disease groups, though was lower in the neurological group (7.8%).

Table 1. Characteristics and overall symptom burden by disease group.

| Cardiovascular (n = 12 923) | Neurological (n = 6935) | Respiratory (n = 6357) | Renal (n = 3062) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Under 65 | 6.1 (782) | 3.4 (237) | 7.9 (499) | 10.8 (332) |

| 65–74 | 12.7 (1642) | 8.7 (605) | 18.0 (1142) | 16.4 (503) |

| 75–84 | 34.4 (4445) | 35.9 (2492) | 37.4 (2379) | 36.1 (1104) |

| 85+ | 46.8 (6052) | 51.9 (3601) | 36.8 (2337) | 36.7 (1123) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48.5 (6267) | 47.0 (3257) | 48.5 (3083) | 53.4 (1634) |

| Female | 51.5 (6654) | 53.0 (3678) | 51.5 (3083) | 46.6 (1428) |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 43.3 (5591) | 48.2 (3343) | 41.7 (2649) | 49.1 (1503) |

| Primary caregiver lives with client | 57.9 (7477) | 63.5 (4403) | 55.8 (3550) | 63.4 (1942) |

| Education | ||||

| Completed Gr. 11 or less | 62.2 (8043) | 60.2 (4177) | 64.1 (4077) | 63.3 (1937) |

| Completed college, university or trade school | 21.6 (2792) | 23.4 (1625) | 18.9 (1199) | 21.4 (656) |

| Patient factors | ||||

| Signs/symptoms of depression (DRS score of > = 3) | 21.3 (2756) | 23.8 (1650) | 22.6 (1438) | 22.0 (672) |

| Moderate to severe impairment in activities of daily living (ADL) (rates 2 and up) | 31.0 (4006) | 50.2 (3483) | 23.4 (1487) | 29.7 (908) |

| Decline in social activities that causes the person distress | 15.1 (1948) | 7.8 (539) | 16.6 (1055) | 16.7 (511) |

| Outcome measures | ||||

| Moderate to severe pain (Pain Scale score > = 2) | 57.2 (7392) | 42.7 (2961) | 58.3 (3708) | 61.0 (1868) |

| Mild to severe cognitive impairment (CPS score of > = 2) | 54.4 (7026) | 91.3 (6330) | 45.2 (2873) | 50.8 (1554) |

| Caregiver experiences feelings of anger, distress or depression | 26.7 (3447) | 37.7 (2612) | 23.9 (1516) | 28.1 (861) |

| Timing of patient’s closest assessment to death | ||||

| 0–4 weeks before death | 20.7 (2676) | 19.3 (1338) | 20.9 (1331) | 21.6 (662) |

| 5–12 weeks before death | 37.2 (4808) | 36.6 (2541) | 37.9 (2410) | 36.2 (1108) |

| 13–26 weeks before death | 42.1 (5439) | 44.1 (3056) | 41.2 (2616) | 42.2 (1292) |

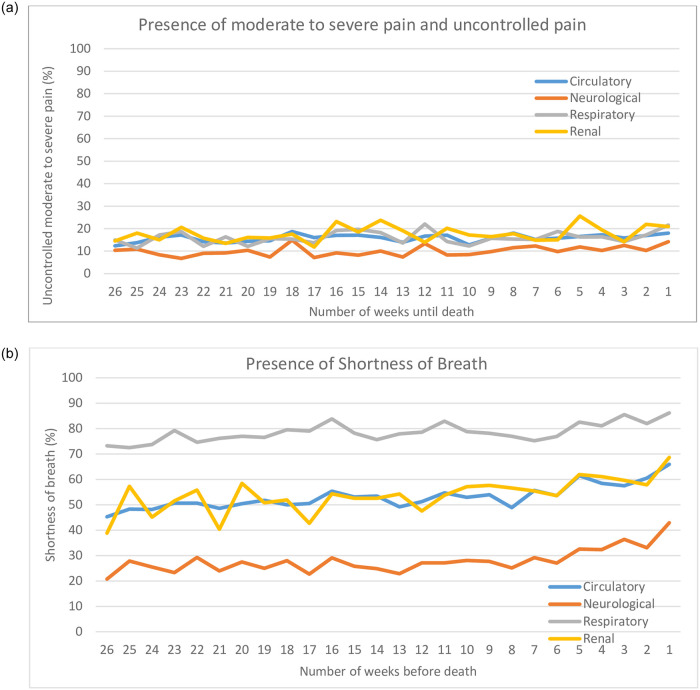

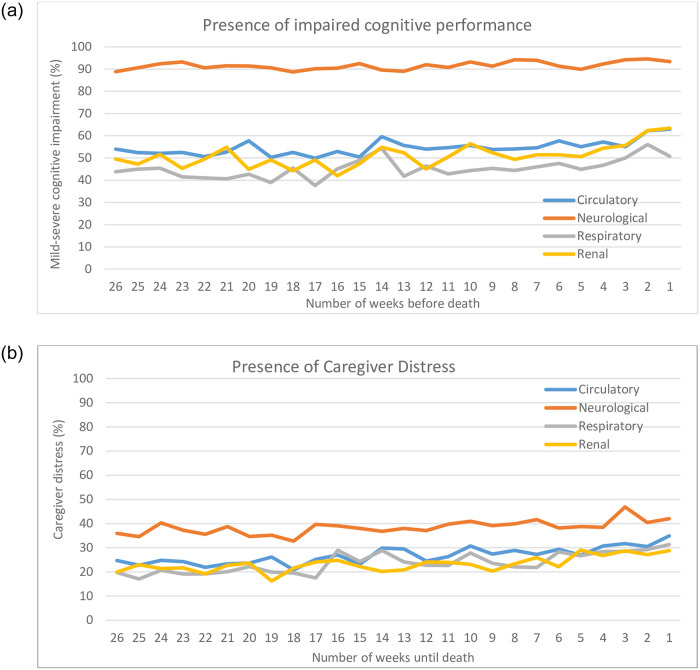

Examining outcomes in the last assessment closest to death, there was a higher prevalence of moderate-severe pain in the cardiovascular (57.2%), renal (61.0%) and respiratory group (58.3%), compared to the neurological group (42.7%) (Table 1). 91.3% of patients with neurological disease had documented mild-severe cognitive impairment. Shortness of breath was reported in 70–85% of patients grouped in the respiratory category. This was on average lower reported in the circulatory, renal, and neurological group (40–65%, 45–65% and 20–40%, respectively).

Mean symptom trajectories over the last 26 weeks of life across the 4 disease groups are shown in Figs 1 and 2. Overall, there was a consistent proportion of patients reporting symptoms prevalence each week across the last 6 months of life for uncontrolled moderate-severe pain, mild-severe cognitive impairment, and caregiver distress; in fact, the prevalence for these symptoms increased slightly by 5–10% closer to death. While moderate to severe pain was reported in nearly half of disease groups, the proportion who also rated that pain as uncontrolled pain dropped to approximately 20% of patients across all disease groups. Cognitive impairment was consistently prevalent in nearly half the disease groups, with the exception being those with neurological disease, where it remained at higher than 90%. Caregiver distress was also evident in about 20% of patients and this proportion rose by 10% or more as one approached death; note neurological disease groups had higher rates over time starting at 35% 6 months before death.

Fig 1. Physical symptom prevalence in the last 6 months of life.

Fig 2. Psychosocial symptom prevalence in the last 6 months of life.

There was more variation in the trajectory of prevalence of shortness of breath. Those with respiratory disease had the highest average prevalence, beginning with a proportion of 73% in the 6 months before death, which rose to 86% in the final week of life. Those with cardiovascular or renal diseases began with roughly 42% reporting shortness of breath, which rose to a prevalence of 69% in the week before death. Neurological disease began at 21% and rose to 43% over the last 6 months of life. Nonetheless, regardless of the disease groups, the prevalence of shortness of breath increased roughly 15%-20% or more in the last four weeks of life. Our sensitivity analysis showed that there was no difference in the symptom trajectories among those who died in hospital vs. died at home across the 4 disease groups.

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression on the factors associated with having the outcomes in the last six months of life. During the last six months of life, age did not consistently affect the odds of reporting symptom scores. Older age increased the likelihood of experiencing shortness of breath (OR: 1.29 to 1.41), impaired cognitive performance (OR: 1.35 to 3.16) and caregiver distress (OR: 1.13 to 1.28). Females had significantly higher odds for reporting uncontrolled pain (OR: 1.24; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.35). Those with neurological disease had higher odds for impaired cognitive performance (9.65; 95% CI, 8.67 to 10.73) and caregiver distress (1.56; 95% CI, 1.43 to 1.71) than those without neurological disease. Those with respiratory disease reported significantly higher odds for shortness of breath (5.37; 95% CI, 5.00 to 5.80) and uncontrolled pain (1.77; 95% CI, 1.61 to 1.96) than those without respiratory disease. Cardiovascular patients reported significantly higher odds for shortness of breath (1.39; 95% CI, 1.29 to 1.50), impaired cognitive performance (1.14; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.23), and caregiver distress (1.28; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.22) compared to those without cardiovascular disease. Patients with renal disease reported significant higher odds for pain (1.21; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.34), shortness of breath (1.18; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.28) and caregiver distress (1.13; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.24) compared to those without renal disease. Those who died in hospital were more likely to have uncontrolled moderate-severe pain (1.11; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.21) and less likely to have cognitive impairment (0.76; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.82).

Table 2. Adjusted odds ratio of having symptoms (moderate to severe pain, shortness of breath, cognitive impairment, caregiver distress, self-reported poor health) in the last six month of life using multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for covariates*.

| Moderate to severe pain and uncontrolled | Shortness of breath | Mild to severe cognitive impairment | Caregiver distress | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||||||

| Age (reference: <65) | 65–74 | 0.69 | (0.59 to 0.82) | 1.29 | (1.11 to 1.50) | 1.35 | (1.15 to 1.57) | 1.13 | (0.69 to 1.33) |

| 75–84 | 0.62 | (0.53 to 0.71) | 1.38 | (1.21 to 1.58) | 1.93 | (1.67 to 2.22) | 1.22 | (1.05 to 1.41) | |

| ≥85 | 0.60 | (0.51 to 0.69) | 1.41 | (1.23 to 1.61) | 3.16 | (2.74 to 3.64) | 1.28 | (1.10 to 1.48) | |

| Sex (reference: male) | Female | 1.24 | (1.15 to 1.35) | 0.97 | (0.91 to 1.03) | 0.94 | (0.88 to 1.01) | 0.76 | (0.71 to 0.81) |

| Cardiovascular Diagnosis (reference: no) | Yes | 0.82 | (0.13 to 1.36) | 1.39 | (1.29 to 1.50) | 1.14 | (1.04 to 1.23) | 1.28 | (1.05 to 1.22) |

| Neurological Diagnosis (reference: no) | Yes | 1.01 | (0.73 to 1.92) | 0.53 | (0.49 to 0.58) | 9.65 | (8.67 to 10.73) | 1.56 | (1.43 to 1.71) |

| Respiratory Diagnosis (reference: no) | Yes | 1.77 | (1.61 to 1.96) | 5.37 | (5.00 to 5.80) | 0.92 | (0.85 to 1.00) | 0.95 | (0.87 to 1.03) |

| Renal Diagnosis (reference: no) | Yes | 1.21 | (1.08 to 1.34) | 1.18 | (1.08 to 1.28) | 1.05 | (0.96 to 1.15) | 1.13 | (1.02 to 1.24) |

| Died in hospital (reference: died at home) | Yes | 1.11 | (1.02 to 1.21) | 0.97 | (0.91 to 1.06) | 0.76 | (0.71 to 0.82) | 1.00 | (0.94 to 1.08) |

* Each of the four models was adjusted for these additional covariates: caregiver lives with patient; moderate-severe impairment in Activities of Daily Living; social decline causing distress; signs and symptoms of depression; and loss of appetite.

** bold indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Discussion

Our data present trajectories of symptoms in the last six months of life in a non-cancer population of home care patients among four disease groups: cardiovascular, neurological, renal, and respiratory. Across all non-cancer disease groups, the trajectory of symptom prevalence increased slightly each week towards death. Cognitive impairment was evident in at least half of the patients in the disease groups, and over 90% in the neurological group. Prevalence of shortness of breath rose by 20% over time across all groups, with the highest prevalence being among those with respiratory disease at 86% in the last week of life. Caregiver distress rose by 10% over time and was prevalent in 35%-40% of patients in the final weeks of life. With a sample size of 20,773 assessments, this is a very large population-based cohort focusing on describing average weekly symptom prevalence among those receiving home care.

Pain, a leading symptom and concern in cancer patients at the end of life [19, 36, 37], was reported as moderate to severe in nearly half or more of the non-cancer cohort, yet only one-fifth described the pain as uncontrolled. This suggests pain may be well-managed by home care services, and pain intensity alone is insufficient to understand one’s overall pain experience. Having renal disease and respiratory disease, respectively, compared to not having those disease, increased one’s odds for moderate to severe uncontrolled pain. Reasons for this are likely complex and multifactorial. Patients with renal and respiratory diseases might not receive enough narcotic treatments, as there are reported concerns in starting higher narcotic treatment strategies in chronic respiratory and renal diseases based on concerns around respiratory depression [36, 38, 39]. Additionally, shortness of breath is known to become more common and severe in the final stage of patients with cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [40]. In our analysis, shortness of breath increased in prevalence across all four disease groups in the final 6 months of life. Patients with respiratory, renal and cardiovascular diseases reported higher prevalence of shortness of breath, in line with other literature [41, 42].

As expected, patients with neurological disease had the highest prevalence of cognitive impairment and caregiver distress among the four groups. This finding supports prior literature linking caregiver distress with caring for a relative with cognitive impairment [43–47]. Caregivers perform a critical role in the socioeconomic context of providing care to a dying patient. To maintain sustainability of this form of care, caregiver needs must be identified, and support systems must be made available accordingly. Ultimately, understanding the trajectory of symptoms and the factors that are associated with increased odds of having complex symptoms can help to identify earlier those who could benefit from palliative care services. This includes non-cancer patients dying at home, where multidisciplinary treatment approaches such as physiotherapy, psychosocial support and better symptom management can improve symptom burden and patient and family outcomes.

Using administrative home care data to describe the weekly average symptom prevalence in the 6 months before death has limitations and strengths. The limitations include the real potential for selection bias in that we lose out on data from patients with very complex symptom issues who then refuse home care services or when they go to hospital; thus, the symptoms of each disease group at those points could be under-reported. We did examine those who died in hospital compared to those who died at home as a sensitivity test, and found no difference in the symptom trajectories, though those dying in hospital were more likely to have uncontrolled pain. Also other data show most terminal hospitalizations are less than 2 weeks and home care is protective of end-of-life hospitalizations [48]. Moreover, it is also possible that those with very complex symptoms would be more willing to accept home care services. Nonetheless, the timing of these formal assessments are typically far apart and only about half the patients had repeated measures, meaning that the trajectories are an average of the cohort and not individual trajectories of symptoms reported weekly. However, a strength of our approach is that it avoids some of the major issues with conducting studies at end of life, which include low recruitment, high missing data, and high attrition rates because patients are too tired or sick to participate [49]. Also in our study, there is virtually no missing data, as the RAI-HC is a mandatory standardized clinical assessment for most individuals receiving publicly-funded home care. Thus, our data is an inclusive population-based cohort, producing a large sample size, and allows us to look at trajectories over time on a weekly basis (for the subset of the cohort who reported in that week).

Other limitations of our data are the inability to have mutually exclusive data for our four analyzed disease groups and control for specific comorbidities. This should be addressed in subsequent research with broader data linkage. Some outcomes, such as shortness of breath, were dichotomous, and do not capture intensity as other validated measures do [50]. Our study is not able to describe the quality of care nor details around symptom management. Since the RAI-HC does not define whether or not the person received specialized palliative care, it is unclear whether changes in treatment plans or initiations of other supportive measures were initiated; this could be addressed in future research. Focusing on users of publicly-funded home care at the end of life means we do not have data on those who did not use home care services, strictly used private home care services, or died in long-term care (approximately 20–25% of the population).

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study describes symptom trajectories in non-cancer home care recipients in Ontario, Canada at end of life. We found across all non-cancer disease groups; the trajectory of symptom prevalence increased slightly each week towards death. Moderate to severe pain was prevalent in nearly half or more of the cohort, but only one-fifth described the pain as uncontrolled. In contrast, shortness of breath, impaired cognitive function and caregiver distress were more highly and consistently prevalent across time near the end of life. Our results suggest the non-cancer population has unmet symptoms needs outside institutional settings.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

Data are available from the Canadian Institute for Health Information for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Interested readers can access these data in the same manner as the authors. These data represent third party data that are not owned nor collected by the study authors. A data request form can be found here: https://www.cihi.ca/en/access-data-and-reports/make-a-data-request.

Funding Statement

This work is funded by the Canadian Centre for Applied Research in Cancer Control (ARCC). ARCC receives core funding from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (grant #2015-703549). The senior author is also supported by the Canada Research Chairs program. Authors otherwise did not receive funding for this work.

References

- 1.Amblas-Novellas J, Murray SA, Espaulella J, Martori JC, Oller R, Martinez-Munoz M, et al. Identifying patients with advanced chronic conditions for a progressive palliative care approach: a cross-sectional study of prognostic indicators related to end-of-life trajectories. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012340. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton R, Rocker G, Dale A, Young J, Hernandez P, Sinuff T. Implementing a palliative care trial in advanced COPD: a feasibility assessment (the COPD IMPACT study). J Palliat Med. 2013;16(1):67–73. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0285 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Palliative care in chronic illness. BMJ. 2005;330(7492):611–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.611 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Developing primary palliative care: primary palliative care services must be better funded by both day and night. BMJ. 2005;330(7492):671. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.671-a . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330(7498):1007–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. Epub 2010/09/08. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–30. Epub 2014/02/25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantin B, Rothuisen LE, Buclin T, Pereira J, Mazzocato C. Referrals of cancer versus non-cancer patients to a palliative care consult team: do they differ? J Palliat Care. 2009;25(2):92–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalkin SM, Lhussier M, Philipson P, Jones D, Cunningham W. Reducing inequalities in care for patients with non-malignant diseases: Insights from a realist evaluation of an integrated palliative care pathway. Palliat Med. 2016;30(7):690–7. doi: 10.1177/0269216315626352 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fassbender K, Watanabe SM. Early palliative care and its translation into oncology practice in Canada: barriers and challenges. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):135–49. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.06.01 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seow H, O’Leary E, Perez R, Tanuseputro P. Access to palliative care by disease trajectory: a population-based cohort of Ontario decedents. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e021147. Epub 2018/04/08. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021147 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn KL, Wegier P, Stukel TA, Huang A, Bell CM, Tanuseputro P. Comparison of Palliative Care Delivery in the Last Year of Life Between Adults With Terminal Noncancer Illness or Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210677. Epub 2021/03/05. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0677 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn KL, Stukel T, Stall NM, Huang A, Isenberg S, Tanuseputro P, et al. Association between palliative care and healthcare outcomes among adults with terminal non-cancer illness: population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m2257. Epub 2020/07/08. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2257 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kite S, Jones K, Tookman A. Specialist palliative care and patients with noncancer diagnoses: the experience of a service. Palliat Med. 1999;13(6):477–84. Epub 2000/03/15. doi: 10.1191/026921699670359259 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luddington L, Cox S, Higginson I, Livesley B. The need for palliative care for patients with non-cancer diseases: a review of the evidence. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001;7(5):221–6. Epub 2002/08/01. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.5.12635 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz K, Lynn J, Dy S, Hughes R, Mularski RA, Shugarman LR, et al. Cancer care quality measures: symptoms and end-of-life care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2006;(137):1–77. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy S, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, Shugarman LR, et al. Quality measures for symptoms and advance care planning in cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4933–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8650 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seow H, Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D, Dudgeon D, Atzema C, et al. Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1151–8. Epub 2011/02/09. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7173 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(5):715–24. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515220 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD007760. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinhauser KE, Arnold RM, Olsen MK, Lindquist J, Hays J, Wood LL, et al. Comparing three life-limiting diseases: does diagnosis matter or is sick, sick? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(3):331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.11.006 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen WJ, Buma S, Gootjes JR, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS, Loer SA. The palliative performance scale applied in high-care residential hospice: a retrospective study. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(1):67–70. Epub 2014/08/15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0645 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bostwick D, Wolf S, Samsa G, Bull J, Taylor DH Jr., Johnson KS, et al. Comparing the Palliative Care Needs of Those With Cancer to Those With Common Non-Cancer Serious Illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(6):1079–84 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.02.014 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris JN, Bernabei R, Ikegami N, Gilgen R, Frijters D, Hirdes JP, et al. RAI-Home Care (RAI-HC) Assessment Manual for Version 2.0. Washington, DC: interRAI Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook RJ, Berg KB, Lee KA, Poss JW, Hirdes JP, Stolee P. Rehabilitation in home care is associated with functional improvement and preferred discharge. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;94(6):1038–47. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook RJ, Berg KB, Lee KA, Poss JW, Hirdes JP, Stolee P. Rehabilitation in home care is associated with functional improvement and preferred discharge. Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(6):1038–47. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirdes JP, Ljunggren G, Morris JN, Frijters DH, Finne-Soveri H, Gray L, et al. Reliability of the interRAI suite of assessment instruments: a 12-country study of an integrated health information system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(277):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H, Jung YI, Sung M, Lee JY, Yoon JY, Yoon JL. Reliability of the interRAI Long Term Care Facilities (LTCF) and interRAI Home Care (HC). Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(2):220–8. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12330 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawes C, Fries BE, James ML, Guihan M. Prospects and pitfalls: use of the RAI-HC assessment by the department of veterans affairs for home care clients. Gerontologist. 2007;47(3):378–87. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fries BE, Simon SE, Morris JN, Flodstrom C, Bookstein FL. Pain in US nursing homes: validating a pain scale for the Minimum Data Set. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(2):173–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–82. Epub 1994/07/01. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin L, Poss JW, Hirdes JP, Jones RN, Stones MJ, Fries BE. Predictors of a new depression diagnosis among older adults admitted to complex continuing care: implications for the Depression Rating Scale (DRS). Age and Ageing. 2008;37(1):51–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris JN, Berg K, Fries BE, Steel K, Howard EP. Scaling functional status within the interRAI suite of assessment instruments. BioMed Central. 2013;13(128):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seow H, Stevens T, Barbera LC, Burge F, McGrail K, Chan KKW, et al. Trajectory of psychosocial symptoms among home care patients with cancer at end-of-life. Psychooncology. 2020. Epub 2020/10/03. doi: 10.1002/pon.5559 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romem A, Tom SE, Beauchene M, Babington L, Scharf SM, Romem A. Pain management at the end of life: A comparative study of cancer, dementia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Palliat Med. 2015;29(5):464–9. Epub 2015/02/15. doi: 10.1177/0269216315570411 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(1):58–69. Epub 2006/01/31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellershaw J, Smith C, Overill S, Walker SE, Aldridge J. Care of the dying: setting standards for symptom control in the last 48 hours of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21(1):12–7. Epub 2001/02/27. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00240-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koncicki HM, Unruh M, Schell JO. Pain Management in CKD: A Guide for Nephrology Providers. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(3):451–60. Epub 2016/11/25. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.08.039 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kuhnbach R, Haberland B, Higginson IJ. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1109–18. Epub 2010/09/15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0068 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2016;69(12):1167. Epub 2016/11/30. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.11.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(3):128–49. Epub 2017/03/10. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.02.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dirikkan F, Baysan Arabaci L, Mutlu E. The caregiver burden and the psychosocial adjustment of caregivers of cardiac failure patients. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2018;46(8):692–701. Epub 2018/12/06. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mavounza C, Ouellet MC, Hudon C. Caregivers’ emotional distress due to neuropsychiatric symptoms of persons with amnestic mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(3):423–30. Epub 2018/12/28. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1544208 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sevilla-Cazes J, Ahmad FS, Bowles KH, Jaskowiak A, Gallagher T, Goldberg LR, et al. Heart Failure Home Management Challenges and Reasons for Readmission: a Qualitative Study to Understand the Patient’s Perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1700–7. Epub 2018/07/12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4542-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soto-Rubio A, Perez-Marin M, Barreto P. Frail elderly with and without cognitive impairment at the end of life: Their emotional state and the wellbeing of their family caregivers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;73:113–9. Epub 2017/08/12. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.07.024 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szeto JY, Mowszowski L, Gilat M, Walton CC, Naismith SL, Lewis SJ. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson’s Disease: Impact on Caregiver Outcomes. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6(3):589–96. Epub 2016/05/11. doi: 10.3233/JPD-160823 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seow H, Qureshi D, Isenberg SR, Tanuseputro P. Access to Palliative Care during a Terminal Hospitalization. J Palliat Med. 2020. Epub 2020/02/06. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0416 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, Yennu S, Bruera E. Attrition rates, reasons, and predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1098–105. Epub 2012/11/08. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27854 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bausewein C, Farquhar M, Booth S, Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Measurement of breathlessness in advanced disease: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2007;101(3):399–410. Epub 2006/08/18. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]