Abstract

Background

There has been substantial progress in research on preventing violence against women and girls (VAWG) in the last 20 years. While the evidence suggests the potential of well-designed curriculum-based interventions that target known risk factors of violence at the community level, this has certain limitations for working in partnership with communities in low- and middle-income (LMIC) countries, particularly when it comes to addressing the power dynamics embedded within north-south research relationships.

Methods

As an alternative approach, we outline the study design for the EVE Project: a formative research project implemented in partnership with community-based researchers in Samoa and Amantaní (Peru) using a participatory co-design approach to VAWG prevention research. We detail the methods we will use to overcome the power dynamics that have been historically embedded in Western research practices, including: collaboratively defining and agreeing research guidelines before the start of the project, co-creating theories of change with community stakeholders, identifying local understandings of violence to inform the selection and measurement of potential outcomes, and co-designing VAWG prevention interventions with communities.

Discussion

Indigenous knowledge and ways of thinking have often been undermined historically by Western research practices, contributing to repeated calls for better recognition of Southern epistemologies. The EVE Project design outlines our collective thinking on how to address this gap and to further VAWG prevention through the meaningful participation of communities affected by violence in the research and design of their own interventions. We also discuss the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the project in ways that have both disrupted and expanded the potential for a better transfer of power to the communities involved. This article offers specific strategies for integrating Southern epistemologies into VAWG research practices in four domains: ethics, theories of change, measurement, and intervention design. Our aim is to create new spaces for engagement between indigenous ways of thinking and the evidence that has been established from the past two decades of VAWG prevention research and practice.

Keywords: Violence against women; indigenous perspectives, Southern epistemologies, Co-design, Participatory research, Samoa, Peru

Background

Over the past 20 years, there has been substantial progress made in research on how to prevent violence against women and girls (VAWG) in low and middle income countries (LMICs) [1, 2]. The extent of the problem and risk factors for VAWG have been well documented [3–5], as have the serious mental and physical health consequences of violence for women’s lives [6–8]. In order to address violence and its consequences in LMICs, available evidence points to the potential of community-based interventions that use group training and community mobilisation techniques to prevent VAWG [9]. A handful of cluster randomised trials of curriculum-based community mobilisation interventions have equally demonstrated that reducing the prevalence of violence in relatively short timeframes is indeed possible [10–12], and recent evidence from the global programme on “What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls” emphasises that carefully planned interventions adapted for local contexts with a clear theory of change can achieve positive outcomes [13].

While well-designed interventions that target risk factors of violence is a useful starting point for thinking about how to design successful VAWG prevention interventions, the adaptation of predefined curricula in different settings around the world raises concerns around power and privilege when working with communities in LMICs with a colonial history. The social and structural factors that contribute to high levels of VAWG, including gender inequalities, extreme poverty and social marginalisation, are often magnified for communities with a legacy of colonialism [14]. For many postcolonial scholars, the violence of colonialism is intimately connected to the high rates of VAWG currently experienced in many LMICs and in aboriginal communities globally [15]. In much the same way, colonialism and new forms of imperialism are often blamed for undermining Southern practices and epistemologies, or ‘ways of knowing’, as part of research practices [16]. This has led to calls for ‘epistemic justice’ through a recognition of Southern epistemologies [17], e.g. theories of how knowledge is obtained, justified and reproduced that are historically aligned with the beliefs and practices of pre-colonial societies. In order to integrate Southern epistemologies into VAWG prevention interventions, the structural inequalities that have marginalised indigenous forms of knowledge need to first be addressed.

Towards this goal, we outline a study design for a novel participatory approach to involving communities affected by violence and with a history of colonialism in the design of their own VAWG prevention interventions. We use a place-based definition of community in this article, whereby communities are geographically and conceptually linked to a location or physical place. We argue that the participation of communities is necessary to address the limitations of current approaches to VAWG prevention research and to reverse the colonial practices that have contributed to the exclusion of a Southern perspective in intervention design and evaluation research. We discuss how the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic has also provided an opportunity for rethinking research relationships and giving more control over research ideas to local communities. As a means of bringing Southern epistemologies into VAWG prevention research, we have prioritised four research-related domains and outline a participatory study to address these domains as part of a strategy for decolonising our own research practices.

Decolonising VAWG research using participatory approaches to intervention design

Throughout the colonial period lasting from the 15th to the late twentieth century, research was often used as a means of re-affirming and consolidating the colonial project and the dominance of the coloniser over the colonised [18, 19]. For example, Turball outlines how Australian aboriginal remains were removed from ancient burial grounds as part of the scientific study of racial difference, and the justification of the colonial belief in the inferiority of aboriginal bodies [20]. Others argue that the extractive tendencies of Euro-Western research practices did not end with the colonial period, and that new forms of imperialism and post-colonial relationships between the researcher and the researched still persist in today’s research practices [21–23]. For instance, Latin American scholars have pointed to the ways in which the legacy of colonialism still configures social life in the region through current economic arrangements and political systems [24].

To address the legacy of colonial histories and new imperial relationships, scholars in Australia, New Zealand and Canada in particular have drawn attention to the importance of an anti-colonial approach to research [25–28]. These scholars point to the essential need to conduct research about indigenous issues in meaningful collaboration with communities and ensure that an indigenous worldview underpins research with direct benefits to the communities involved [16, 29]. Pacific researchers in particular have pointed to a unique ontology of research from the perspective of Pacific indigenous communities founded in relationality rather than individualistic values [28, 30]. Despite growing scholarship that adopts this more critical approach to research practices with indigenous populations [31, 32], an anti-colonial perspective has rarely been applied to research on VAWG prevention. As a potential explanation, scholars point to the hard-won assumption by feminist researchers that VAWG is directly caused by patriarchy and gender inequalities, which can undermine attention to indigenous explanations for VAWG as rooted in structural forms of violence that are also experienced by men [27]. Others have pointed to how the current emphasis on gender inequality as a key driver of violence in Northern scholarship may obscure the way that gender has been historically constituted [33, 34], and how this has been often been accomplished specifically through acts of VAWG (e.g. the rape of indigenous women and its role in reconfiguring sexuality, inheritance and notions of family) [35].

The aim of this article is not to provide a critique of research practices in VAWG research, which has been provided by others [27, 36]. Instead, we reflect on how participatory approaches can be used to create spaces that support dialogue between best practices in VAWG research and Southern epistemologies. This is consistent with what has been described as working as an ‘ally’ with marginalised populations to do their own research, or knowledge-sharing as part of a process of co-production [27, 37]. It also responds to calls for a solidarity-based epistemology characterised by horizontal formations of knowledge and mutual learning [38]. The participation of communities in research design, data collection and analysis is well recognised for its advantages in addressing the power dynamics that underpin research engagements [39], and is often seen as aligned with indigenous approaches to research in the Pacific and Latin American traditions [31, 40]. In this way, participatory research approaches offer a means of surfacing Southern epistemologies by drawing attention to the ‘epistemic privilege’ of mainstream research approaches, exposing the power dynamics embedded in knowledge production, and providing a space for open discussion [41].

This paper is organised around four domains of VAWG prevention research design: (1) ethical guidelines, (2) theories of change, (3) outcome measurement, and (4) intervention development. We discuss each of these domains in turn, briefly summarising the relevant literature within VAWG research and then discussing how we have used participatory methods to bring a Southern perspective into dialogue with the literature as part of the EVE Project (Evidence for Violence prevention in the Extreme).

The EVE project

The EVE Project is a mixed methods participatory project funded by UK Research and Innovation, which started in March 2020. The aim of this research project is to establish an evidence-base for how to prevent VAWG in high-prevalence settings globally (defined as settings with a prevalence of past year physical and/or sexual violence greater than the global median of 11.4%). The project has four main objectives, which are aligned with the four domains of VAWG prevention research design.

Methods/ design

The EVE Project includes two case studies of community-based research with communities to develop VAWG prevention interventions in Amantaní, an island located in Lake Titicaca of the Peruvian Andes, and Samoa, a group of islands in the Polynesian region of the Pacific. Both of these communities are situated in post-colonial contexts: which we have defined as previously colonised spaces, including either nations or populations within countries, characterised by new forms of imperialism [21, 42, 43].

Research settings

Amantaní, Peru

The island of Amantaní is inhabited primarily by a Quechua-speaking indigenous population. This population has reported extremely high rates of partner violence: according to the Demographic and Family Health Survey (ENDES) from 2019, 62.5% of women between the ages of 15 and 49 of native origin, including women self-identified as Quechua, experienced some type of violence exerted by their partner during their lives, markedly higher than the national prevalence (57.7%) [44]. The most common form of violence against women of native origin is psychological and/or verbal (57.5%). In addition, Amantaní is located in the broader region of Puno, which has amongst the highest prevalence rates of intimate partner violence in the country. 63.4% of women living in Puno report ever experiencing violence from a husband or partner, with 37.3% experiencing some form of intimate partner violence within the last year [44]. These high rates reflect socio-cultural views of violence as normal in women’s lives, the way in which Latin American history has reinforced community identities in Andean communities [45], and broader indigenous experiences of discrimination [46].

The Independent State of Samoa

The Pacific islands is the region with the highest prevalence of VAWG in the world: 68% of women will experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime [6]. In Samoa, a recent report from the Office of the Ombudsman reported that 86% of women currently experience physical violence from an intimate partner including kicking, punching and slapping [47]. Samoa has a complex society dating back 3000 years where family (āiga) and village (nu’u) structures are at the heart of social, political and economic organisation [48]. Since the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 1830s, the church also plays a significant role in cultural life and the social organisation of Samoan society [49]. The effects of colonising research practices on understanding these social structures are evident in long-standing debates among anthropologists that represent Samoan society as either inherently violent [50], or a unique example of a culture without conflict [51]. These anthropological accounts of violence in Samoa have been widely critiqued by postcolonial scholars who have highlighted the consequences of misinterpreting the meanings of Samoan cultural traditions through outsider research practices [52, 53].

Community engagement and selection

In both Peru and Samoa, as part of the EVE Project, community-based researchers (CBRs) have been engaged through organisations with a history of working with local communities. Our local Peruvian organisation, Hampi Consultores en salud (https://hampiconsultores.com/), has previously conducted population-based surveys on health and violence with Quechua communities and has significant local contacts and resource networks in the area [54]. Our Samoan partner organisation, the Samoa Victim Support Group (SVSG) (http://www.samoavictimsupport.org/), is a Samoan non-governmental organisation established in 2005 to provide an integrated, personalised, professional service to survivors of domestic violence. SVSG provides training and support for village representatives across Samoa to respond to domestic violence and sexual abuse cases.

The selection of communities in both settings will take into consideration the diversity of the communities, reflecting on dynamics such as community leadership and structure, population, accessibility, and proximity to urban areas. Community selection will also be guided by practical considerations including existing relationships and the level of trust between the implementing organisation and local leaders.

CBR selection and training

Community-based researchers

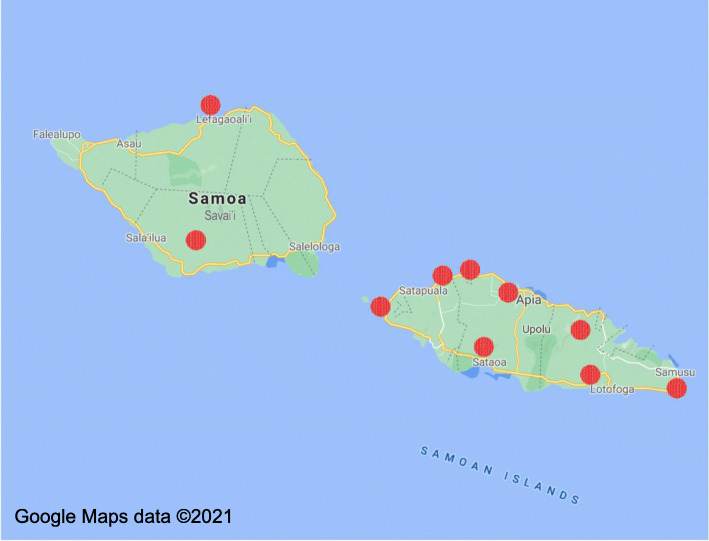

The community-based researchers (CBRs) hired as part of the EVE Project will be responsible for making the majority of decisions about how the project will be implemented. In Samoa, 20 CBRs from 10 villages will be purposively selected by SVSG from their existing network of over 1000 community representatives across the country (see Fig. 1). Selection of CBRs will be based on criteria including: gender balance (one man and one woman from each community), technical knowledge (e.g. ability to use mobile technology), and status within the community (necessary to facilitate community conversations). A mentor will also be selected by the CBRs from their community to ensure that the knowledge of community elders is integrated into the project design from its inception, and that local customs around appropriate communication are taken into consideration [48].

Fig. 1.

Samoan communities (villages) [87]

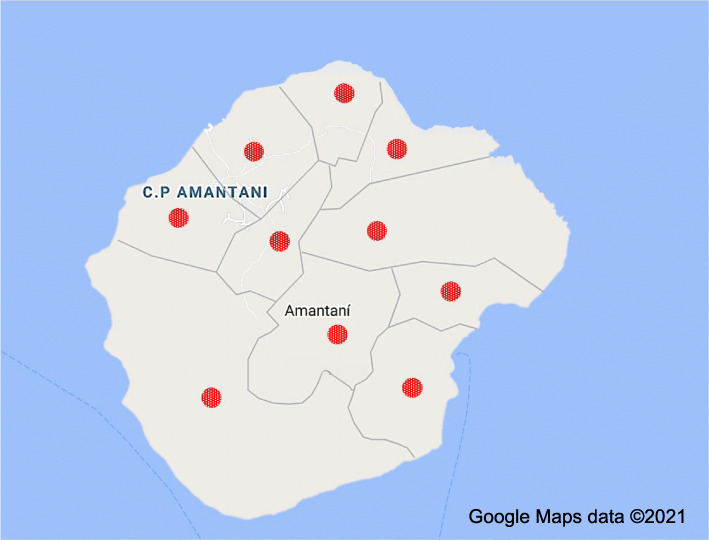

Hampi does not have an existing network of village representatives to draw on, and CBRs will therefore be identified using snowballing techniques and one-to-one conversations with community members and local leaders. A total of 10 CBRs will be identified; one from each of Amantaní’s 10 districts (see Fig. 2). Selection of the CBRs will be based on geographic diversity, and the ability of the CBR to communicate via technology (e.g. mobile phone). Given low literacy rates among women on the island, this will not be a requirement for participation of the CBRs and all activities will be adapted to make their full participation possible. The Amantaní CBRs will all be women to address potential concerns around power dynamics undermining women’s perspectives in mixed groups.

Fig. 2.

Amantaní communities [88]

In both Peru and Samoa, CBRs will be involved in 170 h of structured participatory workshops as part of the project, provided by SVSG and Hampi. These workshops will provide a means of discussing the ideas and assumptions of VAWG scholars about the drivers of violence and strategies for its prevention, and training CBRs in research techniques including semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis. Workshop activities will encourage input by the CBRs into the research process (e.g. by altering topic guide questions and formats, collaboratively discussing participant selection, discussing when privacy may be necessary and how to achieve it, etc.). The research process itself will be done iteratively with the potential for CBRs to make significant changes to the types of data collected, how to analyse these data, and themes to include in the study’s results.

The CBRs will also provide their own data as part of the project through three interviews at the beginning, middle and end. These interviews will be semi-structured to include topics such as their individual experiences to date, any challenges raised, and their own thoughts and ideas about how violence could be prevented in their community. This will help to ensure that every CBR is able to input their own ideas into the project design and not only those who are most outspoken during workshops. It also provides a means of understanding how the project is progressing and the reasons behind challenges or changes that need to be made.

Community participants

The CBRs in each setting will select participants from their communities to participate in the study. During a training workshop on research techniques, CBRs will take part in an activity to discuss who they might select. CBRs will be encouraged to think creatively, considering all community members that may have knowledge on the problem of VAWG, rather than only selecting victims or survivors of violence and community members in positions of power. In Samoa, men will be encouraged to interview men and women to interview women to be considerate of local gender norms and to encourage open and honest dialogue.

Decolonising research about violence against women and girls

The four domains of VAWG research targeted as part of the EVE Project correspond with the project’s objectives and timeline. Each domain represents an independent phase of the project: Phase 1 ‘Developing Ethical Guidelines’; Phase 2 ‘Theory of Change’; Phase 3 ‘Outcome Measurement’; and Phase 4: ‘Intervention development’. We have integrated a space for interaction between the UK-based research team and CBRs, and between the CBRs and the communities they represent as part of each component, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The EVE Project objectives and design components

| Objectives | Design Components | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| To co-create ethical guidelines for violence prevention research and intervention in collaboration with high-prevalence communities | 1. Developing ethical guidelines |

Semi-standardised interviews Participatory hermeneutic analysis |

| To establish the causal mechanisms for how community participation prevents VAWG in high-prevalence settings | 2. Developing theories of change |

Stories of change as case studies Collaborative thematic analysis |

| To develop, validate and feasibility-test new tools for assessing VAWG prevalence in high-prevalence settings | 3. Outcome measurement |

Participatory listing/ ranking exercises Focus group discussions |

| To co-create an intervention in collaboration with high-prevalence communities | 4. Participatory Community-led Intervention Development (PCID) | Participatory action research workshops and activity testing |

Phase 1: developing ethical guidelines

In 2001, researchers belonging to the International Research Network on Violence Against Women (IRNVAW) developed a set of ethical guidelines for VAWG researchers that were later published by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and widely recognised as ethical standards for the field [55]. Several scholars have since discussed how the guidelines need to be adapted for particular settings [56–59]. The adaptations of the WHO guidelines for several purposes and contexts points to the need for a more situated approach to ethical engagement [57, 60]. Towards this goal, the project is designed to use semi-standardised interviews conducted by each CBR with 3–5 community participants to identify the moral decision-making process [61] that community members use to respond to cases of violence. Semi-standardised interviews are a social psychological tool used to investigate subjective theories during the interview process [62]. This is done by asking questions that are designed to elicit both explicit and implicit knowledge on a topic, for example, direct questions about how community members are responding to VAWG and more controversial questions around what participants thought of ideas that are widely accepted by VAWG researchers (e.g. that childhood experiences of violence are a risk factor for experiencing and perpetrating violence later in life) [5].

The CBRs will then participate in a workshop where they will use the data from the interviews to develop a unique set of ethical guidelines for each setting. The aim of the workshop is to ensure that CBRs’ reflections on the moral reasoning of participants provides the basis for the identification of themes from the data. We have developed a unique approach for accomplishing this drawing on a hermeneutic phenomenological analysis of ethical decision-making processes first described by Lindseth and Norberg [63], and adapting it for use as a participatory method as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participatory hermeneutic analysis for the development of ethical guidelines

| Hermeneutic Phenomenological Analysis of ethical decision-making [63] | Participatory hermeneutic analysis for the EVE Project |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: Developing a naïve interpretation of the meaning of the topic under investigation |

Semi-standardised interviews about the meaning of VAWG with community participants, conducted by CBRs; Drawing from the interviews and in collaboration with the research team, CBRs develop a set of guiding phrases for how people should respond to a woman in the community experiencing violence; |

| Stage 2: Identifying themes and sub-themes, and back-checking these against the naïve interpretation |

CBRs identify themes arising from the interviews about decisions around responding to women experiencing violence; Grouping these themes into organising categories (higher order themes); |

| Stage 3: Validate themes against stories of lived experience that tell us about the essence of the topic under investigation |

CBRs validate the guiding phrases about how community members should respond to violence against the themes and categories; Further validation provided through comparison with local myths and stories. |

We will adapt this process to draw directly on the CBRs’ interpretations of the interviews by leading them as a group through a simplified version of these three stages, which results in a set of guiding phrases/ guidelines for how communities (and the research team) should respond to women experiencing violence. This then provides a reference point for developing practical strategies for implementing WHO guidelines, developing new ethical guidelines where needed, and making informed decisions about adaptations to project activities.

Phase 2: Theories of Change

The few models that exist for reducing VAWG primarily draw on the behavioural sciences. These models have been widely used to develop strategies for addressing different risk factors for VAWG, including toxic masculinity, social norms of gender and violence, conflict within family and intimate relationships, and harmful drinking behaviours [64–66]. As part of a decolonising approach, local understandings of violence and community perceptions of its solutions should also inform our theory of change for the EVE Project [67].

To deliver this, we will develop a theory of change in partnership with CBRs using data they have collected from their own communities. This will involve using the semi-standardised interviews collected by CBRs in Phase 1 to collaboratively develop a ‘story’ of violence prevention for each individual community, which can then be used as a case study for analysis. These stories of violence will be developed through a series of participatory activities designed to help CBRs create a narrative from the interviews they have collected. The participatory activities will help facilitate the development of characters for each community’s story, a narrative sequence of events, and a main objective or purpose for the story. The final case studies may discuss either positive or negative examples of violence prevention, and will explicitly talk about how community involvement contributes to either increased or decreased violence in the community. Once developed, the case studies will be collaboratively analysed by the CBRs to identify causal mechanisms of violence prevention evidenced in the community case studies. The co-produced theory of how community involvement contributes to violence prevention will then be presented by the CBRs back to their communities for community discussion and input before being finalised.

The use of storytelling to develop case studies in this way is underpinned methodologically by the importance of stories in both generating spaces for social change and accounting for changes that have taken place. Samoans have rich oral traditions of stories and myths, which have been used by others to understand the rich cultural history of Samoan society [68, 69]. This provides a basis for using stories to understanding local meanings of violence prevention in this study design.

Phase 3: outcome measurement

In the vast majority of VAWG research, the primary outcome of interest is the reduction of VAWG. However, what constitutes violence and what level of reduction is meaningful in the lives of women is highly subjective and context-specific. The vast majority of VAWG survey tools draw on the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) [70], which asks about specific acts of physical violence (e.g. being hit, beaten, slapped, kicked, etc.), psychological abuse, and sexual coercion. While asking about specific acts of violence has provided an opportunity for understanding the extent of violence when individuals may not themselves consider certain actions violent or harmful, the list of actions included in the majority of survey tools fails to account for acts of VAWG that fall outside of the sphere of either intimate partner violence or non-partner rape, such as acid attacks, honour killings, and sexual slavery [71–73]. The CTS and its variations have also been critiqued for not adequately capturing how gender inequalities and contexts of coercive control influence violent behaviours [74, 75]. A broader understanding of the types of violence women may experience may be needed to capture the full extent of the problem in different contexts.

In the EVE Project, we address this by first asking what types of violence are recognised as important to a diverse range of community members during the interviews conducted by CBRs. CBRs will be asked to probe for types of violence that may not be immediately recognised as violence, but that do cause harm to another individual, e.g. economic violence, controlling behaviours, honour-related violence, modern slavery. During the analysis workshop, we will ask CBRs to create a list of types of violence and to use the data to rank the importance of these types according to the importance they hold in women’s lives in each setting. This preliminary conceptualisation of VAWG will then be used as a basis for a series of 4–5 focus groups with women in communities about how the different types of violence impact their everyday lives and what a meaningful reduction in the violence would look like, exploring dimensions of type, frequency, and severity. The findings of these two data collection approaches will provide a basis for selecting and adapting relevant survey tools. The final survey tool will then be further adapted to local epistemologies using cognitive interview techniques [76].

Phase 4: participatory community-led intervention development (PCID)

The EVE Project will use a Participatory Community-led Intervention Development (PCID) approach first developed as part of the Gender-based violence prevention in the Amazon of Peru (GAP) Project [77]. PCID draws on well-recognised components of participatory action research (PAR) including: the participation of targeted groups in the research process to answer the questions they themselves define, a cyclical process of data collection and analysis, and conceptual attention to addressing structural forms of violence through asking critically-informed questions about the problem and proposed solutions (in this case, VAWG) [78, 79]. Similar to PAR, the PCID approach encourages participants to develop understandings of the inequalities that guide their behaviours and develop critical consciousness or conscientização [80] (e.g. about the structural reasons for a high prevalence of violence in their communities). This approach is aligned with the Latin American educationalist Paulo Friere, whose particular pedagogy involves engaging participants in asking critical questions about their lives and experiences rather than ‘teaching’ participants [81]. In the PCID approach, critical consciousness is achieved through engaging participants in identifying the reasons behind VAWG in their communities and designing an intervention to address it as part of the research/action cycle.

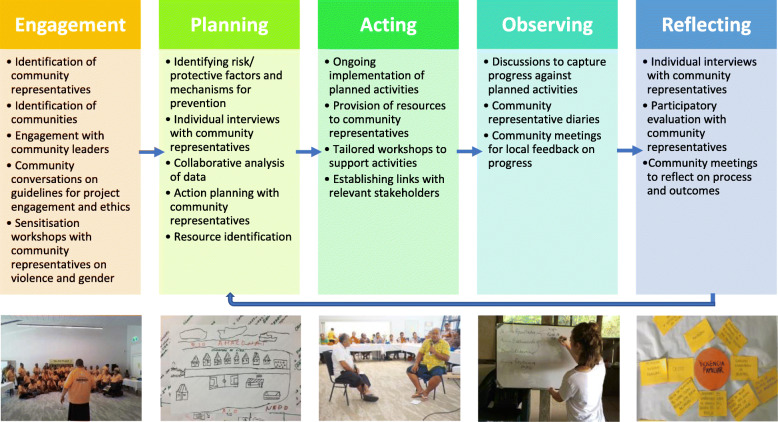

In practice, the PCID approach uses a combination of concept mapping, project management techniques, role play, and participatory evaluation activities with CBRs at different time points, to ensure a shared understanding of relevant concepts and to develop specific VAWG prevention intervention activities for communities as described in Fig. 3. The approach draws on the PAR cycle stages of planning, acting, observing and reflecting, which helps to ensure an iterative intervention design and long-term sustainability with minimal external input [77].

Fig. 3.

Participatory Community-led Intervention Development (PCID) approach for preventing violence against women

Adapting the EVE project for COVID-19

The EVE Project in both Amantaní and Samoa will need to be adapted given restrictions in place surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. The evolving global situation will have a differential impact on the two countries, and adaptations will need to vary across settings. Strict international travel restrictions were implemented in Samoa from as early as January 2020. Since then there have been only three confirmed COVID-19 cases in the country [82]. Whilst international borders remain closed, movement within Samoa is permitted as usual. In Peru, the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were in March 2020. This was promptly followed by a strict national lockdown and a ban on international and domestic travel. At the time of writing, Peru was preparing for a possible third wave of the pandemic with additional tightening of restrictions and very limited mobility within and in and out of the country. The pandemic will impact the activities that can take place.

For example, to develop local ethical guidelines for the projects in both Amantaní and Samoa, the plan is to conduct a series of large community meetings at the beginning of the project to discuss and generate ideas. If this is not possible due to restrictions on large gatherings, ethical guidelines will be developed as part of a longer, more iterative process. CBRs will conduct interviews in their communities and work with the local organisations and the research teams in small groups to collaboratively develop these ethical approaches throughout the project. Moreover, training workshops for CBRs in Samoa will need to be delivered by the local partner organisation with a staff member at the National University of Samoa (NUS) acting as facilitator, instead of the UK research team as originally planned. As a respected local organisation, this will provide an opportunity for SVSG to foster a sense of community and togetherness during the training, which may not otherwise have been possible. This adaptation in particular will contribute towards increasing community involvement and ownership of the project; an overarching objective of the EVE Project.

As a result of restricted travel across Peru, the Peruvian team will conduct a remote health systems assessment as a method of gaining knowledge around the structures in place in Amantaní and Puno (the broader region) before community-based activities can begin. The exploration of how local governance works with regard to VAWG and what services are available to support victims and survivors will help to establish networks within the local area and lay the foundations for the project in Amantaní. Following this, the team will use a small number of local contacts in Amantaní to recruit 10 women as CBRs to begin collecting artefacts relevant to the project. This activity can be done remotely through the use of smartphones to capture images and provide a platform for the sharing of stories. This process will help to gain a better understanding of the local context, whilst also building relationships within the communities for the next phase of the project. This will enable the research process to be much more iterative and flexible, providing greater space for CBRs to contribute to the methodologies involved in the next phase. This is a necessity when working towards a decolonised approach to VAWG research; ensuring that it is informed by local constructions of knowledge and meaning.

Discussion

This EVE Project study design described in this article reflects our collective thinking about how to decolonise our own research practices in VAWG research. This is an iterative process rather than a clearly defined prescriptive procedure. Trying to address power differentials that are embedded in research practices is a constant struggle between reflection, and trial and error. Our study design describes how we have brought social theory and participatory approaches into our reflections about who we are as researchers and the standpoint we take to VAWG prevention and response [21, 22].

We hope that this makes a welcome contribution to the field of VAWG research as part of an ongoing discussion with researchers, practitioners and activists about how we can better account for and recognise Southern epistemologies. The need for community participation to be an integral part of VAWG interventions is widely recognised [83], and the involvement of violence survivors and their communities as stakeholders and partners in research has been adopted as best practice [84]. However, survivors, perpetrators, and the communities they live in, are still rarely involved in the research process itself. They may be considered valuable research participants, but are rarely thought of as potential researchers. As we have argued throughout this article, acknowledging Southern epistemologies in VAWG research will require this integration of the people experiencing the violence into the research process.

The experience of COVID-19 and its impacts on international research relationships has brought the need to reconsider our research practices. The pandemic has demonstrated a clear need to be adaptable and constantly reflective about the ethical challenges and power structures that may be impacted, particularly with research on sensitive topics [85]. For the EVE Project, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to adjust our activities and give far more control over the research design to local partner organisations. We feel strongly that this will be beneficial to the outcomes of the project by making it more context-specific, more localised, and more grounded in Southern epistemologies. This equally provides an important lesson about the need to fundamentally shift the institutional structures that underpin global health research for the longer term [86].

A more critical perspective on decolonising mainstream research methodologies may argue that research frameworks and tools should ideally be developed entirely from the ground up with local communities driving the process according to their own needs [26]. In contrast to this, we have instead chosen a pragmatic approach that tries to establish a dialogue between Western and non-Western epistemologies, while constantly engaging in reflection about how to subvert the power dynamics this entails. This decision has its limitations, but we are optimistic about the possibilities it holds for drawing into question some of the widely held assumptions of VAWG research, while also recognising the decades of both Northern and Southern activism that have gone into shaping the field of VAWG research and practice over the past 20 years.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Peruvian community health workers who were involved in co-designing the PCID approach to intervention development as part of the GAP Project. The Samoa Victim Support Group (SVSG) and EVE Project Teams in Samoa and Amantaní have been instrumental in the development and implementation of the project. This work would not have been possible without them.

Abbreviations

- CBRs

Community-based researchers

- CTS

Conflict tactics scale

- EVE project

Evidence for Violence prevention in the Extreme

- GAP project

Gender-based violence prevention in the Amazon of Peru

- IRNVAW

International Research Network on Violence Against Women

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- NUS

National University of Samoa

- PAR

Participatory action research

- PCID

Participatory community-led intervention development

- SVSG

Samoa Victim Support Group

- VAWG

Violence against women and girls

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

JM wrote the first draft of the article and conceptualised the overall study. The Samoan case study was collaboratively developed by JM, SAA, RB, ECM, HL and LB, while the Peruvian case study was developed by JM, MC, CCV, HL and LB. The PCID approach to intervention development was first developed by JM and GS as part of the GAP Project. All authors contributed to a second and third iteration of the manuscript, and everyone read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Jenevieve Mannell is an Associate Professor in the Institute for Global Health at University College London (UCL). Her research focuses on community responses to violence against women and girls with active projects in Afghanistan, India, Peru, Samoa, and South Africa. She has published extensively on women’s experiences of violence, community participation and methodology, and is an advocate for the participation of communities experiencing high levels of violence in research about their own lives.

Safua Akeli Amaama has been Head of New Zealand Histories & Pacific Cultures at Te Papa Museum in Wellington since 2000. As a historian she has research interests in gender, health, cultural heritage and governance. Previously, she was Director of the Centre for Samoan Studies at the National University of Samoa.

Ramona Boodoosingh is a member of the School of Nursing at the National University of Samoa. Her research interests include capacity development and violence against women. She is currently involved in research on pelvic organ prolapse, food security, obesity, gender and film.

Laura J Brown is a Postdoctoral Researcher at UCL’s Institute for Global Health. She is an interdisciplinary mixed-methods population health scientist whose research centres on a holistic approach to improving women’s health in different environmental contexts. Her research includes exploring environmental links with breastfeeding in the UK and the environment-gender-health nexus in Peru, as well as macro-level quantitative analyses of risk factors for early menarche and menopause in LMICs and intimate partner violence globally.

Maria Calderon is the Director of Hampi Consultores en Salud in Peru and a Peruvian medical doctor, with a Master in Infectious Diseases and International Health from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. In 2017, she led a health need assessment project in Amantani and has worked as an external consultant for the Ministry of Health in Peru and the Peruvian National Institute of Health providing health technology assessment, systematic reviews and policy briefs. She is currently working in Newcastle Upon Tyne Foundation Trust as a research fellow in infectious diseases.

Esther Cowley-Malcolm is a social scientist, Lead facilitator and Lead trainer in the alternatives to violence programme, an educational programme that empowers communities to ‘Create peaceful pathways and alternatives to violence’ in 60 plus countries through-out the world, including Samoa. She has held many roles in relation to research, including research governance, management of the longitudinal “Pacific Islands Pacific study” and has co-authored peer reviewed published papers on interpersonal violence, traditional gift giving in Pacific families and Samoan parenting.

Hattie Lowe is a Research Assistant in the Institute for Global Health at UCL working on the EVE project. She holds an MSc in Reproductive and Sexual Health Research from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Her previous work has focused on gender norms and reproductive health among nomadic pastoralist communities in Kenya and sexual and reproductive health interventions for people with disabilities in LMICs. Hattie is interested in the use of community-based participatory approaches for understanding and improving women’s and adolescent health.

Angélica Motta is an Associate Professor at the Anthropology Department of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos and Director of the Master Program in Gender and Development at the same program. Her research focuses on gender in intersection with health, education, sexuality and violence. Her vast experience in the field includes work in Andean and Amazon communities.

Geordan Shannon is an Australian medical doctor, lecturer in global health and director of the Global Health and Development Masters’ Programme at the UCL Institute of Global Health. Her work focuses on critical approaches to understanding gender and health systems, and transformative, transdisciplinary and transnational approaches to global health with a focus on systems thinking, human-centred design and participatory research.

Helen Tanielu is a Senior Lecturer Sociology in the Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts, National University of Samoa. Her current research focusses on specific factors in Samoan society that need more attention in the design of VAWG/ GBV intervention programs and policies specifically in the context of Samoa. She has published in this area and that of social and community health of Pacific peoples in New Zealand and Samoa. She advocates through work with civil society organizations in Samoa in support of eliminating VAWG.

Carla Cortez-Vergara is a Peruvian medical doctor with specialty in Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. She has training and clinical experience in systemic therapy and in the comprehensive management of mental health problems in children, adolescents, adults and families with an emphasis on prevention. Her research experience focuses on mental health, prevention of mental health problems in children, adolescents, adults and families, and early childhood development.

Funding

Funding for this article and the EVE Project has been provided by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship awarded by the UK Medical Research Council to Dr. Jenevieve Mannell (ref. MR/S033629/1). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from University College London (ref: 9663/002), the National University of Samoa (ref: 2020-06-09), and Comité Institucional de Bioética de Via Libre (ref: 6315). Written signed consent will be taken from all participants involved in the study.

Consent for publication

The images of people provided in Fig. 3 have been published with signed photograph consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jenevieve Mannell, Email: j.mannell@ucl.ac.uk.

Safua Akeli Amaama, Email: safua.akeli@gmail.com.

Ramona Boodoosingh, Email: r.boodoosingh@nus.edu.ws.

Laura Brown, Email: laura.brown@ucl.ac.uk.

Maria Calderon, Email: mariacalderon40@gmail.com.

Esther Cowley-Malcolm, Email: ecm2412@gmail.com.

Hattie Lowe, Email: hattie.lowe@ucl.ac.uk.

Angélica Motta, Email: amottao@unmsm.edu.pe.

Geordan Shannon, Email: geordan.shannon.13@ucl.ac.uk.

Helen Tanielu, Email: h.tanielu@nus.edu.ws.

Carla Cortez Vergara, Email: cortez_vergara@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Bourey C, Williams W, Bernstein EE, Stephenson R. Systematic review of structural interventions for intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries: organizing evidence for prevention health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1165. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temmerman M. Research priorities to address violence against women and girls. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):e38–e40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61840-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):e278–e290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yakubovich AR, Stöckl H, Murray J, Melendez-Torres GJ, Steinert JI, Glavin CEY, et al. Risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence against women: systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective–longitudinal studies. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(7):e1–e11. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Costa BM, Kaestle CE, Walker A, Curtis A, Day A, Toumbourou JW, et al. Longitudinal predictors of domestic violence perpetration and victimization: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2015;24:261–72. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.06.001.

- 6.WHO . Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang EC, Kahle ER, Hirsch JK. Understanding how domestic abuse is associated with greater depressive symptoms in a community sample of female primary care patients: does loss of belongingness matter? Violence Against Women. 2015;21(6):700–711. doi: 10.1177/1077801215576580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eberhard-Gran M, Schei B, Eskild A. Somatic symptoms and diseases are more common in women exposed to violence. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1668–1673. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, Contreras M, et al. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1555–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Abramsky T, Devries KM, Michau L, Nakuti J, Musuya T, Kyegombe N, et al. The impact of SASA!, a community mobilisation intervention, on women’s experiences of intimate partner violence: secondary findings from a cluster randomised trial in Kampala, Uganda. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(8):818–25. 10.1136/jech-2015-206665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wagman JA, Namatovu F, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka D, Nakigozi G, Gray R, et al. A public health approach to intimate partner violence prevention in Uganda: The SHARE project. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(12):1390–412. 10.1177/1077801212474874. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gibbs A, Washington L, Abdelatif N, Chirwa E, Willan S, Shai N, et al. Stepping stones and creating futures intervention to prevent intimate partner violence among young people: cluster randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(3):323–35. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Jewkes R, Willan S, Heise L, Washington L, Shai N, Kerr-Wilson A, et al. Effective design and implementation elements in interventions to prevent violence against women and girls, what works to prevent VAWG? Global Programme Synthesis Product Series; 2020.https://www.whatworks.co.za/resources/evidence-reviews/item/691-effective-design-and-implementation-elements-in-interventions-to-prevent-violence-against-women-and-girls. Accessed 14 Apr 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Montesanti SR. The role of structural and interpersonal violence in the lives of women: a conceptual shift in prevention of gender-based violence. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0247-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mama A. Talking about feminism in Africa. Agenda. 2001;50(2001):58–63. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2001.9675993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos B d S. Epistemologies of the South. Routledge; 2015. 10.4324/9781315634876.

- 18.Green J, Basilico M, Kim H, Farmer P. Colonial medicine and its legacy. In: Reimagining Global Health: An Introduction: University of California Press; 2013. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CXdxDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA33&dq=history+colonialism+in+global+health+research&ots=kaqXxyvbUm&sig=ilQ8GmJ-lNZXDO50tVW-A_C4-kU#v=onepage&q=history colonialism in global health research&f=false. Accessed 14 Apr 2021.

- 19.Birn AE. The stages of international (global) health: histories of success or successes of history? Glob Public Health. 2009;4(1):50–68. doi: 10.1080/17441690802017797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turbull P. Foreign Bodies: Oceania and the Science of Race 1750–1940. 2008. British Anthropological Thought in Colonial Practice: the appropriation of Indigenous Australian bodies, 1860–1880. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanner C. Positionality at the center. Int J Qual Methods. 2015;14(4):160940691561809. doi: 10.1177/1609406915618094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreton-Robinson A. Towards an Australian indigenous Women’s standpoint theory: a methodological tool. Aust Fem Stud. 2013;28(78):331–347. doi: 10.1080/08164649.2013.876664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop R. Freeing Ourselves. Transgressions: Cultural Studies and Education. SensePublishers; 2011. Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quijano A. Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina. In: La Colonialidad Del Saber: Eurocentrismo Yciencias Sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas: CLASCO; 2000.

- 25.Bailey A. Locating Traitorous Identities: Toward a View of Privilege-Cognizant White Character. In: Hypatia. Vol 13. Indiana University Press; 1998:27–42. 10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01368.x, 3

- 26.Held MBE. Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: an unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1609406918821574. doi: 10.1177/1609406918821574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Max K. Chapter Four: Anti-Colonial Research: WORKING as an ALLY with ABORIGINAL PEOPLES. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanga K, Reynolds M. To know more of what it is and what it is not: Pacific research on the move. Pacific Dyn J Interdiscip Res. 2017;1(2):198–204. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson E. Anti-colonial methodologies and practices for settler colonial studies. Settl Colon Stud. 2017;7(4):496–517. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2016.1241213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tualaulelei E, McFall-McCaffery J. 2019. The Pacific research paradigm: opportunities and challenges. MAI A New Zeal J Indig Scholarsh. 2019;8(2):188–204. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaioleti TM. Talanoa Research Methodology: A Developing Position on Pacific Research. Waikato J Educ. 2016;12(1). 10.15663/wje.v12i1.296.

- 32.Tamasese K, Peteru C, Waldegrave C, Bush A. Ole Taeao Afua, the new morning: a qualitative investigation into Samoan perspectives on mental health and culturally appropriate services. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry. 2005;39(4):300–309. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segato RL. Los cauces profundos de la raza latinoamericana: una relectura del mestizaje. In: Critica y Emancipacion: CLASCO; 2010.

- 34.Oyewùmí O. The invention of women: making African sense of Western gender discourses: University of Minnesota Press; 1997.

- 35.Mudimbe VY. The idea of Africa: African Systems of Thought: Indiana University Press; 1994.

- 36.Kea PJ, Roberts-Holmes G. Producing victim identities: female genital mutilation and the politics of asylum claims in the United Kingdom. Identities. 2013;20(1):96–113. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2012.758586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tembo D, Hickey G, Montenegro C, Chandler D, Nelson E, Porter K, et al. Effective engagement and involvement with community stakeholders in the co-production of global health research. BMJ. 2021;372. 10.1136/bmj.n178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Connell R. Meeting at the edge of fear: theory on a world scale. Fem Theory. 2015;16(1):49–66. doi: 10.1177/1464700114562531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minkler M, Wallerstein M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed: Jossey-Bass; 2008.

- 40.Ponton V. Utilizing Pacific Methodologies as Inclusive Practice. SAGE Open. 2018;8(3). 10.1177/2158244018792962.

- 41.Kovach M. Emerging from the margins: Indigenous methodologies. In: Research As Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, & Anti-Oppressive Approaches: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2005. p. 19–36. https://occupyresearchcollective.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/research_as_resistance__critical__indigenous__and_anti_oppressive_approaches1.pdf.

- 42.Harvey D. In what ways is “the new imperialism” really new? Hist Mater. 2007;15(3):57–70. doi: 10.1163/156920607X225870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tikly L. Education and the new imperialism. Comp Educ. 2004;40(2):173–198. doi: 10.1080/0305006042000231347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru). Violencia contra las mujeres, niñas y niños. In: Perú: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar-ENDES 2019 (Peru Demographic and Family Health Survey 2019): National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru); 2020.

- 45.Canessa A. Intimate Indigeneities: Race, Sex and History in the Small Spaces of Andean Life: Duke University Press; 2012. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Intimate_Indigeneities/2McS8Lonb_gC?hl=en&gbpv=1&kptab=overview. 10.1215/9780822395379. Accessed 14 Apr 2021.

- 46.Cripe SM, Espinoza D, Rondon MB, Jimenez ML, Sanchez E, Ojeda N, et al. Preferences for intervention among peruvian women in intimate partner violence relationships. Hisp Heal Care Int. 2015;13(1):27–37. 10.1891/1540-4153.13.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Samoa Office of the Ombudsman . National Public Inquiry into Family Violence in Samoa. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macpherson C, Macpherson L. The Warm Winds of Change: Globalisation and Contemporary Samoa: Auckland University Press; 2009. . https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=8OBaAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT4&dq=cluny+macpherson+samoa&ots=8qov7Gu66F&sig=mmsoZx0eMhqLzwgPQrP5DfN8YpE#v=onepage&q=cluny macpherson samoa&f=false. Accessed 16 Apr 2021.

- 49.Thornton A, Kerslake MT, Binns T. Alienation and obligation: religion and social change in Samoa. Asia Pac Viewp. 2010;51(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8373.2010.01410.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman D. Margaret Mead and Samoa: The making and unmaking of an anthropological myth: Australian National University Press; 1983.

- 51.Mead M. Coming of age in Samoa: a psychological study of primitive youth for Western civilisation: William Morrow Paperbacks; 1928.

- 52.Shankman P. The history of Samoan sexual conduct and the Mead-Freeman controversy. Am Anthropol. 1996;98(3):555–567. doi: 10.1525/aa.1996.98.3.02a00090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas N, Holmes LD. Quest for the Real Samoa: The Mead/Freeman Controversy and Beyond. Vol 23. Greenwood publishing Group; 1988. 10.2307/2802828, 2, 390

- 54.Calderón M, Alvarado-Villacorta R, Barrios M, Quiroz-Robladillo D, Guzmán Naupay DR, Obregon A, et al. Health need assessment in an indigenous high-altitude population living on an island in Lake Titicaca, Perú. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):94. 10.1186/s12939-019-0993-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Ellsberg M, Heise L. Bearing witness: ethics in domestic violence research. Lancet. 2002;359(9317):1599–1604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Contreras-Urbina M, Blackwell A, Murphy M, Ellsberg M. Researching violence against women and girls in South Sudan: ethical and safety considerations and strategies. Confl Heal. 2019;13(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0239-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mannell J, Guta A. The ethics of researching intimate partner violence in global health: a case study from global health research. Glob Public Health 2017;0(0):1–15. doi:10.1080/17441692.2017.1293126, 13, 8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Paavilainen E, Lepistö S, Flinck A. Ethical issues in family violence research in healthcare settings. Nurs Ethics. 2014;21(1):43–52. doi: 10.1177/0969733013486794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sikweyiya Y, Jewkes R. Perceptions and experiences of research participants on gender-based violence community based survey: implications for ethical guidelines. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Houghton C. Young People’s perspectives on participatory ethics: agency, power and impact in domestic abuse research and policy-making. Child Abuse Rev. 2015;24(4):235–248. doi: 10.1002/car.2407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hedgecoe AM. Critical bioethics: beyond the social science critique of applied ethics. Bioethics. 2004;18(2):120–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2004.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flick U. The SAGE Handbook of qualitative data analysis: SAGE Publications; 2014. 10.4135/9781446282243.

- 63.Lindseth A, Norberg A. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18(2):145–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minckas N, Shannon G, Mannell J. The role of participation and community mobilisation in preventing violence against women and girls: a programme review and critique. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1). 10.1080/16549716.2020.1775061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Cislaghi B, Denny EK, Cissé M, Gueye P, Shrestha B, Shrestha PN, et al. Changing social norms: the importance of “organized diffusion” for scaling up community health promotion and women empowerment interventions. Prev Sci. 2019;20(6):936–46. 10.1007/s11121-019-00998-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Abramsky T, Devries KM, Michau L, Nakuti J, Musuya T, Kiss L, et al. Ecological pathways to prevention: how does the SASA! Community mobilisation model work to prevent physical intimate partner violence against women? BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):339. 10.1186/s12889-016-3018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Mannell J, Seyed-Raeisy I, Burgess R, Campbell C. The implications of community responses to intimate partner violence in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2018;13(5). 10.1371/journal.pone.0196584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Lilomaiava-Doktor Oral Traditions, Cultural Significance of Storytelling, and Samoan Understandings of Place or Fanua. Nativ Am Indig Stud. 2020;7(1):121. doi: 10.5749/natiindistudj.7.1.0121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lichtenberg S. Experiencing Samoa through stories: myths and legends of a people and place. Indep Study Proj Collect. Published online April 1, 2011. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1057.

- 70.Straus MA. Conflict Tactics Scale 1979. In: Dahlberg LL, Toal SB, Behrens CB, editors. Measuring Violence-Related Attitudes, Beliefs, and Behaviors Among Youths: Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bsltests/723. Accessed 14 Apr 2021.

- 71.Gibbs A, Said N, Corboz J, Jewkes R. Factors associated with ‘honour killing’ in Afghanistan and the occupied Palestinian Territories: Two cross-sectional studies. PLoS One. 2019;14(8). 10.1371/journal.pone.0219125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Chowdhury EH. Transnationalism reversed: women organizing against gendered violence in Bangladesh. Transnationalism Reversed Women Organ against Gendered Violence Bangladesh. 2011;20(2):1–222. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2012.698916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahmad L, Anctil AP. Misogyny in ‘post-war’ Afghanistan: the changing frames of sexual and gender-based violence. J Gend Stud. 2018;27(1):86–101. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2016.1210002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Myhill A. Measuring domestic violence: context is everything. J Gender-Based Violence. 2017;1(1):33–44. doi: 10.1332/239868017X14896674831496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walby S, Towers J, Balderston S, et al. The Concept and Measurement of Violence against Women and Men: Policy Press; 2017. 10.26530/oapen_623150.

- 76.Willis GB. Analysis of the cognitive interview in questionnaire design. Public Opin Q. Published online 2015.

- 77.Shannon G, Mannell J. Participation and power: Engaging peer researchers in preventing gender-based violence in the Peruvian Amazon. In: Bell S, Aggleton P, Gibson A, editors. Peer Research in Health and Social Development: International Perspectives on Participatory Research. Routledge: Forthcoming; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brydon-Miller M. Participatory action research: psychology and social change. J Soc Issues. 1997. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1997.tb02454.x.

- 79.O’Grady M. The Sage handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. Action Learn Res Pract. 2013;10(2):195–199. doi: 10.1080/14767333.2013.799394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freire P. Pedagogy_of_the_Oppressed_30th_Anniversary_Edition_----_(Chapter_4): Bloomsbury Publishing; 2005.

- 81.Smith WA. The meaning of Conscientizacao: The goal of Paulo Freire’s pedagogy. Published online 1976. Accessed May 12, 2020. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=cie_nonformaleducation

- 82.Worldometer. Samoa COVID: 3 Cases and 0 Deaths - Worldometer. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/samoa/

- 83.Daruwalla N, MacHchhar U, Pantvaidya S, et al. Community interventions to prevent violence against women and girls in informal settlements in Mumbai: The SNEHA-TARA pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):743. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Glass N, Perrin N, Clough A, Desgroppes A, Kaburu FN, Melton J, et al. Evaluating the communities care program: best practice for rigorous research to evaluate gender based violence prevention and response programs in humanitarian settings. Confl Heal. 2018;12(1):1–10. 10.1186/s13031-018-0138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Townsend E, Nielsen E, Allister R, Cassidy SA. Key ethical questions for research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):381–383. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30150-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mannell J, Abubakar I, Bastawrous A, Osrin D, Patel P, Piot P, et al. UK’s role in global health research innovation. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):721–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30303-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Google Maps. The Independent State of Samoa. . https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Samoa/@-13.7688769,-172.4025259,9.41z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x71a513a364ec1003:0xa6870c9674617872!8m2!3d-13.759029!4d-172.104629

- 88.Google Maps. Isla Amantaní, Peru. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Amantaní/@-15.6647654,-69.7275935,14z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x915d78dbe94fc57b:0xc292df5c2fc0bbf3!8m2!3d-15.6662082!4d-69.710821%0A

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.