Abstract

The actual number of individuals infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is difficult to estimate using a case-reporting system (i.e., passive surveillance) alone because of asymptomatic infection. While wastewater-based epidemiology has been implemented as an alternative/additional monitoring tool to reduce reporting bias, the relationship between passive and wastewater surveillance data has not yet been explicitly examined. As there is strong age dependency in the symptomatic ratio of SARS-CoV-2 infections, here, we aimed to estimate i) an age-dependent association between the number of reported cases and viral load in wastewater and ii) the time lag between these time series. The viral load in wastewater was modeled as a combination of contributions from virus shedding by different age groups, incorporating the delay, and fitted with daily case count data collected from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration in wastewater recorded by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. The estimated lag between the time series of viral loads in wastewater and of reported cases was 10.8 (95% confidence interval: 10.2–11.6) and 8.8 (8.4–9.1) days for the northern and southern areas of the wastewater treatment plant, respectively. The estimated contribution rate of a reported case to the viral load in wastewater in the 0–19 yr age group was 0.38 (0.35–0.41) and 0.40 (0.37–0.43) for the northern and southern areas, and that in the 80+ yr age group was 0.67 (0.65–0.69) and 0.51 (0.49–0.52) for the northern and southern areas, respectively. The estimated lag between these time series suggested the predictability of reported cases 10 days later using viral loads in wastewater. The contribution of a reported case in passive surveillance to the viral load in wastewater differed by age, suggesting a large variation in viral shedding kinetics among age groups.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Wastewater, Wastewater-based epidemiology, Mathematical modeling

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WBE, wastewater-based epidemiology; PMMoV, pepper mild mottle virus

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Following the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2019 (Huang et al., 2020), the epidemic has resulted in a large number of deaths worldwide. The development of effective pharmaceutical interventions for the eradication of SARS-CoV-2 is ongoing, and non-pharmaceutical interventions (i.e., restriction of movement) are still required to reduce the risk of mortality. For the latter to be effective, an understanding of the current state of the epidemic is needed. In infectious disease epidemiology, the time series of the number of confirmed cases is monitored (known as passive surveillance) and used to understand the current state of an epidemic. However, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, such data have large biases because the testing frequency and propensity are not constant over time, and therefore, the sampling process is non-random (Omori et al., 2020a). For instance, the number of confirmed cases strongly depends on the number of people who recognize their infection or suspicious contact with infected individuals. SARS-CoV-2 is known to cause asymptomatic infections, and the rate of symptomatic infection depends on age (Kronbichler et al., 2020; Omori et al., 2020b). These characteristics make it difficult to estimate the actual number of incidences from the number of confirmed cases, necessitating alternative approaches to identify these potentially unreported transmissions.

In this context, wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) has garnered the attention of scientists (Bivins et al., 2020) and public health authorities (COVID-19 WBE Collaborative, 2021; Naughton et al., 2021). Even during the initial phase of the epidemic, SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in wastewater was reported in various countries including Australia (Ahmed et al., 2020), Japan (Haramoto et al., 2020), the United States (Sherchan et al., 2020), and several countries in Europe (La Rosa et al., 2020; Medema et al., 2020). The Netherlands has already implemented a nationwide wastewater monitoring system (The Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), 2020), and more than 40 states in the United States have utilized WBE (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021; Wu et al., 2021). While this system has potential as an early warning system, considerable challenges remain (Zhu et al., 2021). For instance, although several studies have conducted lagged correlation analysis (Nemudryi et al., 2020; Peccia et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020), there is a lack of explicit modeling methods that can relate the observed viral load in wastewater to the number of infected individuals.

To capture trends in ongoing transmissions from the viral load in wastewater, it is essential to understand their quantitative relationship. While the detection rate by passive surveillance strongly depends on the age of individuals, resulting in a bias in the number of confirmed cases, in principle, the viral load in wastewater reflects the actual infection levels in communities as long as the wastewater monitoring methods (i.e., condition of influent samples, timing of wastewater sampling, and virus detection protocols) are consistent over time. Therefore, a comparison between passive surveillance and wastewater surveillance could quantitatively measure age-dependent biases in passive surveillance.

In the present study, we aimed to estimate the age-dependent association between the number of reported cases in passive surveillance and the viral load in wastewater to compare passive and wastewater surveillance methods. We constructed a statistical model describing the association between incidence per age group and the viral load in wastewater, and then estimated the lag of detection timing between passive surveillance and wastewater surveillance and age dependency in the contribution rate of incidences to the viral load in wastewater.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

Daily case count data were collected from situation reports produced by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (the Massachusetts Department of Public Health). “Confirmed” case was defined as a patient who met confirmatory laboratory criteria (i.e., detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a clinical or autopsy specimen using a molecular amplification test) (Council of State and Terrotoral Edpidemiologists, 2021). As age-specific data were available only until August 11, 2020, we analyzed the case series from March 22 through that date.

For wastewater, we used data from the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, including the SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration measured by Biobot Analytics (Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, 2020). The wastewater treatment facility used has two major influent streams (“northern” and “southern”), and wastewater samplings were conducted 3–7 times per week for each influent stream. The concentration of SARS-CoV-2 was normalized to the concentration of a human fecal indicator (PMMoV) to compensate for variations in fecal load in wastewater, which can be affected by factors such as fecal excretion patterns and dilution. Details of the sampling and molecular methods were described in a previous study (Wu et al., 2020).

2.2. Model

To understand the heterogeneity in the contribution of an incidence to the viral load in wastewater by age, age-group-specific incidences were compared to the viral load in wastewater. Assuming that the lag between the detection timing from wastewater and reporting by passive surveillance is similar between age groups, the viral load in wastewater at time t, w(t), can be written as follows:

| (1) |

where, τ denotes the lag between the detection timing from wastewater and reporting by passive surveillance, i a denotes the incidence in age group a, and k a denotes the contribution rate of an incidence in age group a to the viral load in wastewater. This model was fitted to the data for viral load in wastewater w data(t) by maximizing the likelihood function considering the Poisson sampling process, L:

| (2) |

We then calculated profile likelihood-based confidence intervals for each parameter. In the model, i a(t) was defined as the change in continuous time, but the sampling times of real data were discrete. To obtain this variable in continuous time, we determined the 2-week moving average of the reported cases from passive surveillance by cubic spline interpolation.

To understand the heterogeneity in the contribution of age-group-specific reported cases, we conducted a multiple regression analysis between the number of reported cases by passive surveillance and the viral load in wastewater. The coefficients in the model, k as, were compared to evaluate the contribution of each age group. The relative evaluation of coefficients in multiple regression is biased by multicollinearity if the explanatory variables (in our study, the number of reported cases per age group) are strongly correlated. To reduce this bias, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients between pairs of explanatory variables in the model (i a in Eq. (1)). If the correlation coefficient was >0.7, one of two explanatory variables was excluded until all correlation coefficients were <0.7. All of the above computations were implemented in Mathematica ver. 12.0.0.0.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Multicollinearity in the regression model of viral load in wastewater

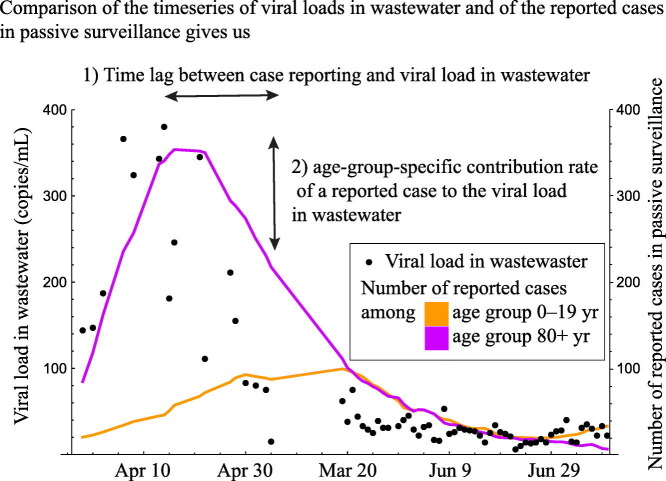

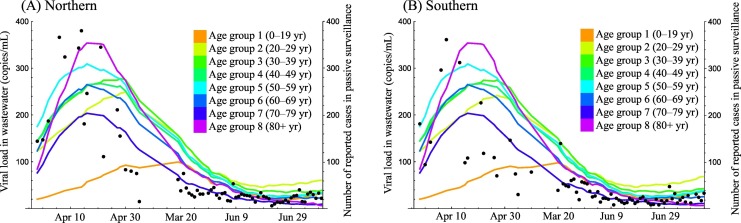

There were strong correlations in the number of reported cases by passive surveillance between age groups (Table 1 ), with an expected large bias in the multiple regression analysis. As shown in Fig. 1 , the time-series trends in the number of reported cases between the close age groups were similar. This similarity can be considered to induce multicollinearity in the regression model. The time series of reported cases by passive surveillance in age groups 0–19 years and 80+ years were chosen as the explanatory variables to satisfy the criteria. In the selected model, all correlation coefficients between explanatory variables were <0.7.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients of the time series of reported cases by passive surveillance between different age group pairs.

| Age group (yr) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | ||

| Age group | 0–19 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| 20–29 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.70 | ||

| 30–39 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.82 | |||

| 40–49 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.84 | ||||

| 50–59 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.83 | |||||

| 60–69 | 0.93 | 0.88 | ||||||

| 70–79 | 0.97 | |||||||

Fig. 1.

Comparison between the viral load in wastewater and the number of reported cases per age group in passive surveillance. Dots show the viral load in wastewater sampled in the (A) northern and (B) southern areas of the treatment plant. Solid lines show the 2-week moving average of the number of reported cases per age group in passive surveillance, with color representing age group.

3.2. Model fittings

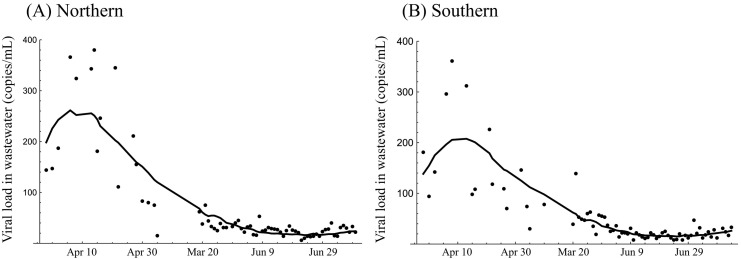

We used the model described in Eq. (1) to estimate the lag between the detection timing from wastewater and reporting from passive surveillance, τ, and the contribution rate of an incidence in age group a to the viral load in wastewater, k a. The maximum likelihood estimate of τ was 10.8 (95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 10.2–11.6) for the northern area and 8.8 (95% CI: 8.4–9.1) days for the southern area. The maximum likelihood estimate of k a for the age group 0–19 yr was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.35–0.41) for the northern area and 0.40 (95% CI: 0.37–0.43) for the southern area. The maximum likelihood estimate of k a for the age group 80+ yr was 0.67 (95% CI: 0.65–0.69) for the northern area and 0.51 (95% CI: 0.49–0.52) for the southern areas. The model's estimated parameters reasonably explained the data for viral load in wastewater sampled in both northern and southern areas (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Model fittings to the viral load in wastewater sampled in the (A) northern and (B) southern areas. Solid lines show the model prediction and dots show the viral load in wastewater.

Our estimated length of lag between the detection timing from wastewater and reporting by passive surveillance suggested that the former can occur earlier than the latter. Our estimated length of lag, 8.4–11.6 days, agrees with that of previous studies; monitoring of the viral load in wastewater can detect the outbreak 5–11 days ahead of passive surveillance if a delay of 0–3 days from symptom onset to reporting is assumed (Nemudryi et al., 2020; Peccia et al., 2020; Rusinol et al., 2021). Compared to the incubation period of SARS-CoV-2 (Guan et al., 2020; Lauer et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020), our estimate of τ suggests that the virus is discharged from the body to sewers in the early stages of infection. These results also suggest the potential success of early outbreak detection using wastewater. The estimated lag length was similar between the areas. The lag length was related to the natural history of the pathogen (i.e., the timing of virus discharge from body to sewer and the timing of symptom onset, which triggers testing in passive surveillance) and testing capacity. These factors were likely similar between the areas because of geographical proximity. It should also be noted that the lag length can depend on the diagnosis rate in passive surveillance. A previous study reported that the lag length decreased or disappeared over time (Rusinol et al., 2021), which suggests that early outbreak detection using wastewater can be successful only when the testing rate in passive surveillance is low, for example, in the early stage of outbreak.

The contribution of reported cases from the passive survey in age group 80+ yr to the viral load in wastewater was larger than that in age group 0–19 yr, a trend that was similar between both areas. This estimate suggests that the amount of virus shedding to wastewater by young individuals was smaller than that by elderly individuals. Furthermore, as the rate of asymptomatic infection among young individuals is higher than that among the elderly individuals (Kronbichler et al., 2020), the amount of virus shedding to wastewater among individuals with asymptomatic infection may be smaller than that among individuals with symptomatic infection. Because a previous study showed the association between viral loads from respiratory tract and urine and severity of illness (Fajnzylber et al., 2020), it can be assumed that the amount of virus shedding to wastewater is also associated with the severity of illness. Furthermore, the increase in symptom severity in elderly patients because of the increase in intestinal SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 expression has been proposed (Vuille-dit-Bille et al., 2020). This suggests the association of viral load in feces (and fecal shedding prevalence) with age. On the contrary, the number of confirmed cases from passive surveillance largely depends on the rate of symptomatic infection. If the amount of virus shedding to wastewater depends on the severity of symptoms, wastewater surveillance will also be affected by the rate of symptomatic infection.

The goodness of fit was better for the decreasing parts of the time series (Fig. 2). This might be because the beginning of the time series contained too many uncertainties (e.g., the difficulty in the prediction of the number of infected individuals due to the large variation in the amount of virus shedding to wastewater at individual level (Miura et al., 2021), under-reporting in passive surveillance, and substantial heterogeneity in viral load within a sewer system across time and space). However, another possible interpretation is that the estimability of parameters is ensured by an observation period that contains rich information on the clearance of viruses from infected individuals. In such a case, the difference in shedding kinetics among age groups determines the temporal changes in the viral load in wastewater. Because the viral RNA in serum persists longer in patients with severe illness (van Riel et al., 2021), it can be hypothesized that elderly individuals who tend to exhibit severe illness show a prolonged shedding pattern in feces. In such a case, it is likely that prolonged higher viral concentrations would be observed in wastewater if the age composition in the given community has subgroups with elderly individuals. Although previous studies have investigated the duration of shedding or its time course with mainly symptomatic patient data (Han et al., 2020; Miura et al., 2021; Wolfel et al., 2020), further studies on the determinants of the excretion characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 are needed.

4. Conclusions

The estimated lag between the time series of viral loads in wastewater and of reported cases in passive surveillance suggested the predictability of reported cases 10 days later using viral loads in wastewater. Our modeling of the association between passive and wastewater surveillance showed that the contribution of a reported case in passive surveillance to the viral load in wastewater differed by age, emphasizing the importance of understanding age-dependent shedding kinetics. Further insights into the relationship between the amount of virus discharge to wastewater, age, and severity of symptoms would improve the predictive ability of WBE and make it more robust as a surveillance system.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ryosuke Omori: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Fuminari Miura: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Masaaki Kitajima: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by JST, CREST [grant number JPMJCR20H1]; JSPS KAKENHI [grant number 20J00793], and Grants-in-Aid for Cross Departmental Young Researcher Grants of Hokkaido University, Japan.

Editor: Damia Barcelo

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O’Brien J.W., et al. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., North D., Ahmad A., Ahmed W., Alm E., Been F., et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology: global collaborative to maximize contributions in the fight against COVID-19. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:7754–7757. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2021. National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) [Google Scholar]

- Council of State and Terrotoral Edpidemiologists . 2021. Update to the Standardized Surveillance Case Definition and National Notification for 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 WBE Collaborative. 2021.

- Fajnzylber J., Regan J., Coxen K., Corry H., Wong C., Rosenthal A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 2020:11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y., Liang W.-H., Ou C.-Q., He J.-X., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.S., Seong M.W., Kim N., Shin S., Cho S.I., Park H., et al. Viral RNA load in mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic children with COVID-19, Seoul, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:2497–2499. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Malla B., Thakali O., Kitajima M. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.L., Wang Y.M., Li X.W., Ren L.L., Zhao J.P., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronbichler A., Kresse D., Yoon S., Lee K.H., Effenberger M., Shin J.I. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;98:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Iaconelli M., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Bonadonna L., et al. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Water Resources Authority . 2020. Wastewater COVID-19 Tracking. [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura F., Kitajima M., Omori R. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding in faeces as a parameter for wastewater-based epidemiology: re-analysis of patient data using a shedding dynamics model. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;769 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton C.C., Roman F.A., AGF Alvarado, Tariqi A.Q., Deeming M.A., Bibby K., et al. 2021. Show us the Data: Global COVID-19 Wastewater Monitoring Efforts, Equity, and Gaps. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemudryi A., Nemudraia A., Wiegand T., Surya K., Buyukyoruk M., Cicha C., et al. Temporal detection and phylogenetic assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater. Cell Rep. Med. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori R., Mizumoto K., Chowell G. Changes in testing rates could mask the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) growth rate. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:116–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori R., Mizumoto K., Nishiura H. Ascertainment rate of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Japan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;96:673–675. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccia J., Zulli A., Brackney D.E., Grubaugh N.D., Kaplan E.H., Casanovas-Massana A., et al. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1164–1167. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinol M., Zammit I., Itarte M., Fores E., Martinez-Puchol S., Girones R., et al. Monitoring waves of the COVID-19 pandemic: inferences from WWTPs of different sizes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;787 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherchan S.P., Shahin S., Ward L.M., Tandukar S., Aw T.G., Schmitz B., et al. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater in North America: a study in Louisiana, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) 2020. Coronavirus Monitoring in Sewage Research. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- van Riel D., Embregts C.W.E., Sips G.J., van den Akker J.P.C., Endeman H., van Nood E., et al. Temporal kinetics of RNAemia and associated systemic cytokines in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. mSphere. 2021 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00311-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuille-dit-Bille R.N., Liechty K.W., Verrey F., Guglielmetti L.C. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 gene expression in small intestine correlates with age. Amino Acids. 2020;52:1063–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00726-020-02870-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Muller M.A., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Xiao A., Zhang J., Moniz K., Endo N., Armas F., et al. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Titers in Wastewater Foreshadow Dynamics and Clinical Presentation of New COVID-19 Cases. Medrxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Xiao A., Zhang J., Moniz K., Endo N., Armas F., et al. 2021. Wastewater Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 across 40 US States. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Oishi W., Maruo C., Saito M., Chen R., Kitajima M., et al. Early warning of COVID-19 via wastewater-based epidemiology: potential and bottlenecks. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;767 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]