Abstract

Emergency physician empathy and communication is increasingly important and influences patient satisfaction. This study investigated if there is a need for improvement in provider empathy and communication in our emergency department and what areas could be targeted for future improvement. Patients cared for by emergency physicians with the lowest satisfaction scores were surveyed within 1 week of discharge. Patients rated their emergency provider’s empathy and communication and provided feedback on the patient–provider interaction. Compared to survey responses nationally, our providers fell between the 10th and 25th percentiles for all questions, except question 5 (making a plan of action with [the patient]) which was between the 5th and 10th percentile. Areas most frequently cited for improvement were “wanting to know why” (N = 30), “time is short” (N = 15), and “listen to the patient” (N = 13). Survey percentiles and open-ended suggestions demonstrate a need for providers to give thorough explanations, spend more time with the patient, and demonstrate active listening. These themes can be used to strengthen the provider–patient relationship.

Keywords: clinician–patient relationship, communication, emergency medicine, empathy

Background

The patient experience has become increasingly important in health care quality improvement initiatives. Patient satisfaction has an impact on adherence to treatment, clinical outcomes, readmission, profitability (1), emergency department (ED) utilization, and willingness to return (2). The emergency department is often a patient’s first experience during a hospital admission and impacts their impressions of the health care system. The ED visits typically occur during stressful times for patients, and the ED is often chaotic, overcrowded, and has a lack of patient privacy, which provides a challenge for establishing positive patient perceptions (3). Furthermore, the emergency physician is simultaneously tasked with caring for multiple patients, managing high-acuity situations, and limited by time constraints, which can further impact patient satisfaction (4). Prior qualitative research has shown patients cite wait times, staff–patient communication, staff empathy, and provider compassion as the greatest factors impacting their ED experience (2,3).

Although wait times impact patient satisfaction, this variable is beyond the limits of a single-quality improvement intervention as it is dependent on many factors, such as staffing, resource allocation, patient utilization, and the hospital–ED interface. The remaining factors impacting patient satisfaction comprise key components of the doctor–patient relationship (5 -13). This relationship is especially important in the high stakes environment of the ED where patients are vulnerable and ineffective communication can lead to detrimental patient outcomes and complications (4,14 –17). Prior research has shown that emergency physicians focus more attention on information gathering than information delivery during a patient’s encounter, frequently interrupt patients, and do not give detailed discharge instructions (18). This conflicts with patients’ expectations that their ED visit will be centered on understanding the causes and implications of their symptoms, reassurance, achieving symptom relief, and having a plan to manage symptoms and complications postdischarge (19).

Although prior work has identified provider empathy and communication as drivers of patient satisfaction, there is a paucity of specific patient-provided and action-oriented suggestions for improving this aspect of the patient–provider relationship (3). Our study seeks to identify if there is a need to improve physician empathy and communication in our ED. Should this need exist, we also investigate what specific areas of provider empathy and communication should be targeted for overall improvement.

Methods

Survey Development

Our research team developed a survey based on the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) survey, a tool with previously validated results measuring patient perceptions of empathy (20). Patients were asked 5 questions related to their recent physician–patient interaction in our ED. The 5 questions were chosen specifically to highlight aspects of patient expectations of an ED visit as laid out in the study by Villancourt et al mentioned above (19). Questions included, “How good was the physician at (1) really listening, (2) showing care and compassion, (3) fully understanding your concerns, (4) explaining things clearly, and (5) making a plan of action with you.” Prior research has shown a correlation between Press Ganey surveys and other surveys that partially inquire about the patient–provider relationship. However, the CARE survey tool has yet to be translated in the unique environment of the ED, presenting an opportunity for a more detailed empathy and communication investigation. After survey development, the research proposal was sent to the institutional review board (IRB) of the Mayo Clinic Arizona. The IRB deemed the study exempt, given minimal risk to participants and quality improvement nature of the project. The survey was pilot tested by all members of the research team to ensure content clarity and interview flow. No quantitative survey questions were added or removed after pilot testing. However to better capture a wide range of patient frameworks, the team added a series of open-ended questions asking about what else the provider could do to improve empathy and compassion (see Supplement 1).

Participant Recruitment

We surveyed patients within 1 week of discharge by the Mayo Clinic Arizona ED providers, with the lowest patient satisfaction scores as indicated by the Press Ganey survey. The goal was to capture a potential association between low satisfaction scores and patient perceived empathy and communication skills, should an association exist. It also offered the potential to target future empathy and communication improvement initiatives for providers with lower scores. A prior review of patient satisfaction scores indicates improving interpersonal interactions may lead to improved satisfaction scores (21). While prior work has suggested this, we hoped to better elucidate this relationship through our purposeful sampling. The providers with the lowest patient satisfaction scores were blinded to the study, with hopes of not biasing their typical patient care interaction framework. We wanted to avoid as much as possible a Hawthorne effect, and for this reason, we did not let providers know we were surveying their patients. Each week a report of patients discharged by these selected providers was deidentified and distributed to the research team. Patients less than age 18 were excluded from the study. Verbal consent was obtained, and patients were interviewed by trained research associates. Patients were asked 5 questions from the CARE survey and they rated their agreement with the statements on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“completely agree”). Patients were then asked to provide open-ended feedback to further assess how, if at all, empathy and communication could be improved in our local ED. These open-ended responses were recorded, transcribed, deidentified, and organized in Dropbox until they were later pooled together for final analysis within Dedoose software. Deidentified quantitative survey responses were recorded in Google spreadsheets and then reformatted into Microsoft Excel for final analysis within STATA). Data collection occurred between February and May 2020.

Quantitative Analysis

Using a convergent parallel mixed-method approach, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected during the patient phone calls and analyzed together after data collection was complete. CARE survey question-specific responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics and were then compared across providers to identify any one provider that had a significant difference in survey responses. The question-specific quantitative analysis compared average and median response scores for each of the 5 survey questions.

Qualitative Analysis

Participants’ transcribed and deidentified qualitative responses to how, if at all, provider care could be improved were analyzed by S.A. using primary inductive coding. S.A. then collapsed primary codes into broader codes, and S.A. and K.J. developed and refined the codebook. S.A. and K.J. used this finalized codebook to independently recode each transcript, using the constant comparative method until adequate agreement achieved (Cohen’s κ >.8). The codes were collapsed and final thematic analysis completed within a framework grounded in prior patient–provider relationship literature.

Results

Demographic Data

A total of 780 patients were called between February and May 2020. Of these, a total of 221 patients (response rate of 28.33%) agreed to participate in the phone survey. The majority of the patients who participated in the survey were between the ages of 51 and 75 (44.8%) and were female (50.7%).

Quantitative Responses

Patient quantitative scores for the survey questions ranged from a mean of 4.16 to 4.47, with question 5 (clear discharge plan) having the lowest mean and question 4 (clear explanations) having the highest mean (Table 1). Given the overall high CARE survey ratings, the data were not normally distributed and aggregate medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were also analyzed. The median score across all 5 questions was 5 and IQR 4 to 5 for all questions, except question 2 that focused on care and compassion. Survey question averages as well as medians were not significantly different across the 4 providers (P values: .12-.32), and all providers had question-specific averages greater than 3 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Aggregate Quantitative Results From the CARE Phone Survey.

| CARE survey question (topic discussed) | Mean (SD) | Median score (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Question 1 (listening) | 4.4 (1.12) | 5 (4–5) |

| Question 2 (care/compassion) | 4.45 (1.09) | 5 (5–5) |

| Question 3 (understanding concerns) | 4.36 (1.16) | 5 (4–5) |

| Question 4 (clear explanations) | 4.47 (1.03) | 5 (4–5) |

| Question 5 (clear discharge plan) | 4.16 (1.38) | 5 (4–5) |

| Total | 21.85 (5.18) | 25 (21-25) |

Abbreviations: CARE, Consultation and Relational Empathy; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Comparison of CARE Survey Reponses Across Providers.

| CARE survey question (topic discussed) | Provider 1 median score (IQR) | Provider 1 mean score (SD) | Provider 2 median score (IQR) | Provider 2 mean score (SD) | Provider 3 median score (IQR) | Provider 3 mean score (SD) | Provider 4 median score (IQR) | Provider 4 mean score (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 (listening) | 5 (5–5) | 4.5 (1.15) | 5 (4–5) | 4.5 (0.89) | 5 (4–5) | 4.6 (1.16) | 5 (3–5) | 4.15 (1.2) | .12 |

| Question 2 (care/compassion) | 5 (5–5) | 4.6 (1.10) | 5 (5–5) | 4.52 (0.98) | 5 (5–5) | 4.67 (1.04) | 5 (3–5) | 4.22 (1.16) | .15 |

| Question 3 (understanding concerns) | 5 (5–5) | 4.47 (1.15) | 5 (4–5) | 4.48 (0.91) | 5 (5–5) | 4.56 (1.12) | 5 (3–5) | 4.13 (1.31) | .32 |

| Question 4 (clear explanations) | 5 (4–5) | 4.47 (1.11) | 5 (4–5) | 4.43 (0.91) | 5 (5–5) | 4.76 (0.93) | 5 (4–5) | 4.34 (1.12) | .12 |

| Question 5 (clear discharge plan) | 5 (5–5) | 4.3 (1.40) | 5 (4–5) | 4.02 (1.37) | 5 (5–5) | 4.49 (1.14) | 5 (3–5) | 4.0 (1.49) | .30 |

| Total | 25 (23.5-25) | 22.35 (5.63) | 24 (21-25) | 21.96 (3.99) | 25 (24-25) | 23.07 (5.1) | 24 (16-25) | 20.85 (5.57) | .009 |

Abbreviations: CARE, Consultation and Relational Empathy; IQR, interquartile range.

Qualitative Analysis

A total of 221 patients offered feedback to the open-ended question at the end of the survey. From this feedback, a total of 135 patients commented on areas where their care could be improved. Of the remaining 86, 43 patients commented on aspects of their visit that went well, and the rest reported they had no suggestions improving the patient–provider interaction.

Requesting improved explanations

Of the 135 open-ended patient suggestions, better provider explanation was a theme most frequently cited by patients. Within this theme, codes of “wanting to know why” (N = 30) and “wanting clear discharge explanations” (N = 10) emerged (Figure 1). Patients discussed wanting clear explanations for all aspects of their treatment plan and medical encounter, expressing frustrations when providers are “so focused what’s going on and how can I help you and then not as focused on explaining or taking time with me.” Others stated they were unsure of how their clinical course would continue after the ED visit and were unsure about how to utilize certain equipment given to them at the time of discharge. This related closely to patients’ frustrations with diagnostic expectations (N = 4), which could have possibly been ameliorated if the provider explained why their symptoms did or did not fit with patient’s perceived symptom and diagnosis pairings.

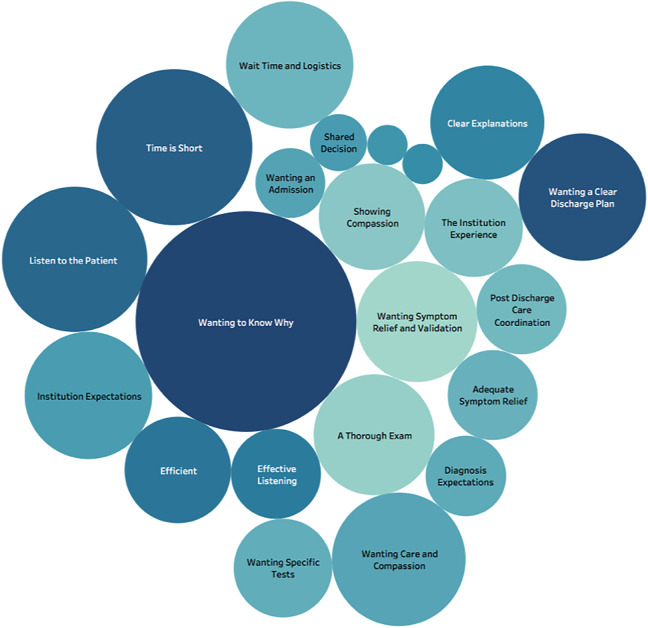

Figure 1.

Patient priorities for provider empathy and communication size of circles correlate with the frequency that patients cite a qualitative theme in areas of provider empathy and communication. Patients most frequently emphasized themes related to the provider–patient interaction, such as “wanting to know why,” “time is short,” and “listen to the patient” and less frequently emphasized care logistic themes of “wanting specific tests” or “postdischarge care coordination.”

Listening to the patient

Another frequently cited theme was patients wanting their provider to listen to them (N = 13). Some gave suggestions on how providers could more effectively show patients they were actively listening:

“[The provider] could have verbalized back to me like ‘so what you are saying is this is what happened and this is how you felt and you are concerned by such and such.”

Others expressed that this improved listening could take the form of symptom validation (N = 9). Patients expressed feeling their symptoms were not serious enough to warrant an ED visit when they felt poorly listened to. One patient said the provider made her feel “stupid that [the patient] even went in” to the ED. Beyond symptom validation, patients also cited wanting general care and compassion from their provider (N = 11) during all aspects of the clinical encounter.

An emphasis on quality time

Many patients reported feeling the provider did not spend enough time with them (N = 15), despite few (N = 10) suggesting that wait times were a component of their ED visit frustrations. Multiple patients cited feeling “rushed” by the provider when the provider was in the room. Some patients even expressed understanding that the ED is busy and an understanding of realistic expectations in regard to an ED provider’s time; however, they also emphasized that when a provider is in their examination room, they want the provider’s full attention. This theme of having a provider’s undivided attention also incorporated the code of wanting a thorough examination (N = 9). Patients wanted the physician to look at and lay hands on the areas of concern, even if patients knew they would also be receiving other tests and imaging necessary for diagnosis.

“I just think that [the provider] was fine except the no hands on type thing which I was not used to. At least [the provider] could have looked at my legs more closely or felt for pulses. Maybe listened to my lungs or felt my abdomen.”

Patients expressed wanting more hands on care. They often used adverbs or adjectives such as “more closely” and “more thoroughly,” placing and emphasis on quality time, not just on the exact metric of minutes spent in the room.

Logistical concerns

Similar to few patients describing wait times as highly influencing their provider satisfaction ratings, patients rarely cited external logistics outside the provider’s control. When logistical themes did come up, patients discussed wanting a hospital admission (N = 3) and wanting specific tests ordered (N = 6) as the other potential areas of improvement. However, the want for specific tests could easily be collapsed under the theme of wanting a more thorough explanation of what diagnostic tests they would need and why. Patients also expressed concerns about postdischarge care coordination between specialties (N = 5), and thus, only a total of 18 of the 135 patients cited logistical factors as future areas for ED quality improvement. When asked for suggestions for improvement, interestingly several patients expressed a high regard for the institution, and because of this, they did not report action-item suggestions, but rather a perspective of holding higher expectations for their ED care in general, and focused on comparing their recent ED visit with prior non-ED care evaluations or subspecialty procedures (N = 10).

How patients appreciate care

Of the 221 patients surveyed, 43 patients offered unsolicited positive feedback on what aspects of their visit that went well. Some patients expressed gratitude with how the physician showed support throughout their visit, including showing care and compassion (N = 8), giving clear explanations (N = 8), effective listening (N = 5), and offering shared decision-making (N = 2). This was best conveyed by one patient who stated the physician: “…talked with me and not to me.”

Patients also appreciated how efficient the providers were (N = 7) in their ability to complete their evaluation and discharge them from the ED in a timely manner. Others expressed that they were thankful the provider gave them adequate symptom relief (N = 5) and correctly diagnosed their problem (N = 1). A fair number of patients stated that they were happy with their care because of their broader positive feelings toward the institution (N = 6). Patients seemed to place the institution in high regard, which was reflected in unsolicited comments such as “[the institution] is number 1 in my books,” or “I love [the institution], it’s amazing over there. I have had no problems.” This preconceived expectation seemed to create some leniency, such that even if patients thought there were areas for improvement, they wanted to highlight that “anyone who has a bad experience at [the institution] just doesn’t have a realistic idea of what it takes to run this sort of facility” (Table 3).

Table 3.

Thematic Analysis.

| Themes | Sample quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient frustrations | Codes | |

| A thorough examination | “I hit my head and [the provider] didn’t even touch my head, [the provider] just sent me to go get x-rays.” | |

| Diagnosis expectations | “…[the provider] thought I had a low blood pressure episode cause I had diabetes. But when I got home, I realized I could have very well been dehydrated because they have very similar symptoms. I think I very well was dehydrated. So [the provider] didn’t look into that option.” | |

| Institution expectations | “The good feelings I have toward [the institution] are part of why I was so disappointed.” | |

| Listen to the patient | “[The provider] could have actually listened to our concerns and did something about the infection that I had instead of ignoring me and my mom[‘s] concern and walking out of the room as we were talking to [the provider].” | |

| Postdischarge care coordination | “[The provider] understood the problem and got a hold of the ophthalmologist and told me that he would see me that day but that I had to call him at 8 am to set that up. Given my level of concern and anxiety it would have been nice for this appointment to have been set up internally.” | |

| Time is short | “I think spent more time. I was there for almost 5 hours. And I saw [the provider] for a total of 10 minutes. It didn’t seem like my situation was important to [the provider], like it didn’t deserve [the provider’s] time.” | |

| Wait time and logistics | “The only thing is we got to the hospital at 9:30 pm and we left at 5:30 am in the morning. In the respect, it was really lengthy. I don’t know how they could improve on that but improve in ways that it wouldn’t take so long.” | |

| Wanting a clear discharge plan | “I guess I just didn’t even see [the provider] at the end of the visit, a nurse just kinda gave me my discharge info, and I was supposed to get a filter to bring home which I didn’t receive.” | |

| Wanting an admission | “My situation was when I came back the next day, I needed to be admitted. My symptoms were the same on Sunday as on Monday but [the provider] didn’t admit me. I wish I would have gotten started on everything a little sooner.” | |

| Wanting care and compassion | “I have a history of IV drug abuse and endocarditis with a replaced valve…. I felt like they were like ‘you’ve been in here 3 times before with this and if this happens a fourth time don’t bother coming back’ and like addiction is a disease too and I just don’t feel like they cared about me.” | |

| Wanting-specific tests | “I would have slept better if I had been given an ultrasound. I’m fine now and the leg is getting better but if I would have had a blood clot I could have been dead right now.” | |

| Wanting symptom relief and validation | “I realize they were extremely busy that day I will give [them] that. I walked away with the feeling, “your bone is not broken, what are you complaining about?” It didn’t feel very good.” | |

| Wanting to know why | “I guess…I didn’t know what all the tests were for…It would have been nice to know what all the results meant. Like if [the provider] explained why [they were] ordering something or what [they] found from it. Like to know the blood test I gave was normal, urine test was normal. Or this is what we found, it lines up with your symptoms.” | |

| How patients’ appreciate care | ||

| Adequate symptom relief | “I left with the feeling that I was on the right drug, the right cycle, and that I would get better.” | |

| Clear explanations | “Well, I think [the provider] sat down and zeroed in on what I was saying and asked more questions. [the provider] made sure I was clear on what [the provider] was saying before I left so I don’t think [the provider] could have done anything else.” | |

| Diagnostic appreciation | “[The provider] diagnosed it right away and at the end was spot on, so kudos to him.” | |

| Effective listening | “[The provider] was patient and listened carefully and responded to every comment or question.” | |

| Efficient | “I was very happy that they were methodical but quick, got me in and out as fast as possible.” | |

| Shared decision-making | “I was extremely impressed with [the provider’s] willingness to involve me in the decision-making process.” | |

| Showing compassion | “[The provider] made it comfortable for me in a time where you can’t get in contact with your normal doctor.” | |

| Showing support | “I did not want to stay in the hospital – and it was a severe thing but [the provider] was very supportive about my reasoning.” | |

| The institution experience | “The [institution] is number one in my book and I am from out of state. They make you feel better…it is the nicest place to go. I really don’t have any negative feelings.” | |

Discussion

By completing quantitative and qualitative analyses of patients’ perceptions of emergency provider empathy and communication, we aimed to determine what aspects of the doctor–patient relationship most significantly impact patient satisfaction at our institution. Although patients rated provider empathy and communication highly using the quantitative scale, qualitative analysis of patient’s responses provided specific aspects of the patient–provider interaction that can be targeted for future quality improvement.

Overall, patients rated provider empathy and communication highly, with question averages falling between a mean of 4.16 and 4.48 on a 5-point scale and median responses of 5 out of 5 across all of the CARE survey questions. However, when these results are compared against patient responses for the CARE survey nationally (22), our providers fall between the 10th and 25th percentiles for patient satisfaction with provider listening, care and compassion, fully understanding a patient’s concerns, and giving clear explanations (questions 1-4). Our providers fell between the 5th and 10th percentile for patients’ satisfaction with a clear plan of action after the visit (question 5). This question also received the lowest average score of a 4.16. The CARE survey is an internationally used survey that was created in the department of general practice in Edinburgh University and Glasgow University. The survey is mostly used by general practitioners, and because of this, we recognize that compared to a population of patients who have longitudinal relationships with their providers, our ED providers are going to fall in a lower percentile. Furthermore, our providers fell in the lowest percentile for their ability to give a clear plan of action after the visit. This is an area that is inherently challenging for a specialty with no patient follow-up, which makes it difficult to compare with longitudinal primary care practices. Our providers lower CARE survey scores relative to the national average also correlate with the participant selection of surveying patients cared for by providers with the lowest Press Ganey satisfaction survey scores. However, similar to prior CARE survey responses, our data are also right skewed, making it difficult to detect differences across providers, evaluate improvements, or advocate for empathy and communication training interventions. A benefit of the qualitative analysis is showing specific areas potentially needing improvement such as patients wanting to know why (N = 30), wanting more time spent with the doctor (N = 15), wanting better provider listening (N = 13), and wanting care and compassion (N = 11). It also allowed patients to voice concerns that fell outside the patient–provider relationship, such as issues with wait times and hospital logistics (N = 10) or wanting a clear discharge plan (N = 10).

Although prior qualitative investigations showed that patients most frequently cited wait times as an area for patient satisfaction improvement in the ED, our patients focused less on logistical concerns and more on provider-sided factors (2). A few patients surveyed did voice concerns about wait times, the busy environment of the ED, and technology issues. However, patients more commonly wanted changes relating to aspects of the doctor–patient relationship. Many of the patients’ suggestions for improvement fell under the umbrella theme of “wanting to know why.” This category encompasses patients’ desires for easy to understand, yet thorough, explanations about aspects of their health care ranging from medical diagnosis to treatment options to visit progression and test results. One patient remarked, “I just wish [the provider] went over [their] concerns, the treatments that would be done, and which doctors would be working with me moving forward.” Interestingly, even in areas where patients talked about wait times or other external factors outside the provider’s control, the provider could have provided an explanation to mitigate many of their concerns. One patient said, “I think that during my 6-hour wait, [the provider] could have come around and explained why the wait was taking so long. This would have given me a lot of reassurance.”

Patients’ desires for clear explanations, wanting to be heard by the provider, and wanting time spent with the provider all demonstrate a patients’ wish to play an active role in their health care and to be a central member of the health care team. Our results provide us with targeted recommendations to improve and strengthen provider–patient relationships in our ED going forward. However, the themes cited by patients in our study are not just specific to ED care. These themes can be easily applied to any specialty, as they are all key aspects of the doctor–patient relationship.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, we chose to only survey patients seen by providers with the lowest satisfaction scores. In choosing to not survey all patients seen in our ED, we may have missed opportunities for patients who otherwise rated their provider highly, to provide broader general suggestions for areas of improvement for our ED. In addition, this patient cohort could have provided suggestions for things providers do well which their colleagues should adopt. However, literature suggests that targeting interpersonal communication skill improvement should be the focus of future patient satisfaction quality improvement interventions (21). It is possible that all providers could learn from patient suggestions discovered by this analysis. The 28% of patients wiling to complete the phone survey may have been a biased cohort, which could have skewed the data. However, despite their overall positive quantitative responses, many offered open-ended suggestions for how emergency providers could improve their future patient–provider experience. In addition, the novel use of the CARE survey in the ED setting could have biased the results since these questions were originally validated for general practitioners who have more time to spend with patients. Lastly, our study was conducted in a large tertiary care ED with a national reputation, with some patients referencing this institutional reputation as a reason for why they had a positive perspective toward the ED and also as a reason for why they expected more from the providers. These unique and preconceived expectations of our patient population may not be generalizable or transferrable to other EDs in a community setting.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrates that while patients rate local ED providers highly on scores of empathy and communication, when compared nationally to CARE survey responses, our providers fall in the bottom percentiles. Although the novel use of the CARE survey within the ED is not necessarily generalizable to prior general practitioner metrics, open-ended responses demonstrate room for improvement. Patients emphasize targeting specific areas such as providing patients with thorough explanations, use of active listening techniques, and maximizing time spent with patients. Although results were based on providers with the lowest satisfaction scores, future efforts will include giving all ED physicians within this practice access to this quality improvement data so as to identify and improve upon weaknesses in regard to physician empathy and communication.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_2374373521996981 for Patient Suggestions to Improve Emergency Physician Empathy and Communication by Sophia Aguirre, Kristen M Jogerst, Zachary Ginsberg, Sandeep Voleti, Puneet Bhullar, Joshua Spegman, Taylor Viggiano, Jessica Monas and Douglas Rappaport in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jpx-10.1177_2374373521996981 for Patient Suggestions to Improve Emergency Physician Empathy and Communication by Sophia Aguirre, Kristen M Jogerst, Zachary Ginsberg, Sandeep Voleti, Puneet Bhullar, Joshua Spegman, Taylor Viggiano, Jessica Monas and Douglas Rappaport in Journal of Patient Experience

Author Biographies

Sophia Aguirre is from Tucson, Arizona. She is a current third year medical student at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine in Arizona.

Kristen M Jogerst is a current general surgery resident physician at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Zachary Ginsberg was born in Canada but raised in Scottsdale, Arizona. He is a current second year medical student at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine in Arizona.

Sandeep Voleti was raised in Queens, New York. He is a current second year medical student at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine in Arizona.

Puneet Bhullar was raised in Tracy, California. She is a current third year medical student at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine in Arizona.

Joshua Spegman was raised in Tucson, Arizona. He is a current third year medical student at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine in Arizona.

Taylor Viggiano was raised in Scottsdale, Arizona. She is a current second year medical student at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine in Arizona.

Jessica Monas is a current practicing Emergency Medicine physician at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Douglas Rappaport is a current practicing Emergency Medicine physician at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The institutional review board deemed the study exempt given minimal risk to participants and quality improvement nature of the project. Patient consent was obtained verbally before proceeding with survey questions.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Sophia Aguirre  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8197-1735

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8197-1735

Zachary Ginsberg  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2809-1560

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2809-1560

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Richter JP, Muhlestein DB. Patient experience and hospital profitability: is there a link? Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Natsui S, Aaronson EL, Joseph TA, Natsui S, Aaronson EL, Joseph TA. et al. Calling on the patient’s perspective in emergency medicine: analysis of 1 year of a patient callback program. J Patient Exp. 2019;6:318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sonis JD, Aaronson EL, Lee RY, Philpotts LL, White BA. Emergency department patient experience: a systematic review of the literature. J Patient Exp. 2018;5:101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ackermann S, Bingisser MB, Heierle A, Langewitz W, Hertwig R, Bingisser R. Discharge communication in the emergency department: physicians underestimate the time needed. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86:359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Welch SJ. Twenty years of patient satisfaction research applied to the emergency department: a qualitative review. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruberton PM, Huynh HP, Miller TA, Kruse E, Chancellor J, Lyubomirsky S. The relationship between physician humility, physician–patient communication, and patient health. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Waard CS, Poot AJ, den Elzen WPJ, Wind AW, Caljouw MAA, Gussekloo J. Perceived doctor-patient relationship and satisfaction with general practitioner care in older persons in residential homes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2018;36:189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walsh S, O’Neill A, Hannigan A, Harmon D. Patient-rated physician empathy and patient satisfaction during pain clinic consultations. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188:1379–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang H, Kline JA, Jackson BE, Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Cowden CD. et al. Association between emergency physician self-reported empathy and patient satisfaction. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaitoff A, Sun B, Windover A, Bokar D, Featherall J, Rothberg MB. et al. Associations between physician empathy, physician characteristics, and standardized measures of patient experience. Acad Med. 2017;92:1464–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, Lyna P, Coffman CJ, Dolor RJ. et al. Physician empathy and listening: associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:665–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaelber DC, Bates DW. Health information exchange and patient safety. J Biomed Inform 2007;40:S40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scotten M, Manos EL, Malicoat A, Paolo AM. Minding the gap: interprofessional communication during inpatient and post discharge chasm care. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:895–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bartlett G, Blais R, Tamblyn R, Clermont RJ, MacGibbon B. Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. CMAJ. 2008;178:1555–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rhodes KV, Vieth T, He T, Miller A, Howes DS, Bailey O. et al. Resuscitating the physician-patient relationship: emergency department communication in an academic medical center. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaillancourt S, Seaton MB, Schull MJ, Cheng AHY, Beaton DE, Laupacis A. et al. Patients’ perspectives on outcomes of care after discharge from the emergency department: a qualitative study. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70:648–58.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mercer SW, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. The Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) measure: development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam Pract. 2004;21:699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boudreaux ED, O’Hea EL. Patient satisfaction in the emergency department: a review of the literature and implications for practice. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Department of General Practice at Edinburgh University and Glasgow University. CARE measure certificate for sample user, physiotherapist. Published 2012. Accessed November 30, 2020. www.caremeasure.org/samplereport.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_2374373521996981 for Patient Suggestions to Improve Emergency Physician Empathy and Communication by Sophia Aguirre, Kristen M Jogerst, Zachary Ginsberg, Sandeep Voleti, Puneet Bhullar, Joshua Spegman, Taylor Viggiano, Jessica Monas and Douglas Rappaport in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jpx-10.1177_2374373521996981 for Patient Suggestions to Improve Emergency Physician Empathy and Communication by Sophia Aguirre, Kristen M Jogerst, Zachary Ginsberg, Sandeep Voleti, Puneet Bhullar, Joshua Spegman, Taylor Viggiano, Jessica Monas and Douglas Rappaport in Journal of Patient Experience