Abstract

Background:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exposed nurses to a rapidly changing patient care practice. This study explored nurses’ experiences in caring for COVID-19 patients.

Methods:

Eighteen nurses, head nurses, and clinical supervisors employed in one of the hospitals affiliated to the Shahid Beheshti Medical University to participate in this qualitative content analysis study. Data were collected through interviews and field notes. The data were analyzed with conventional content analysis.

Results:

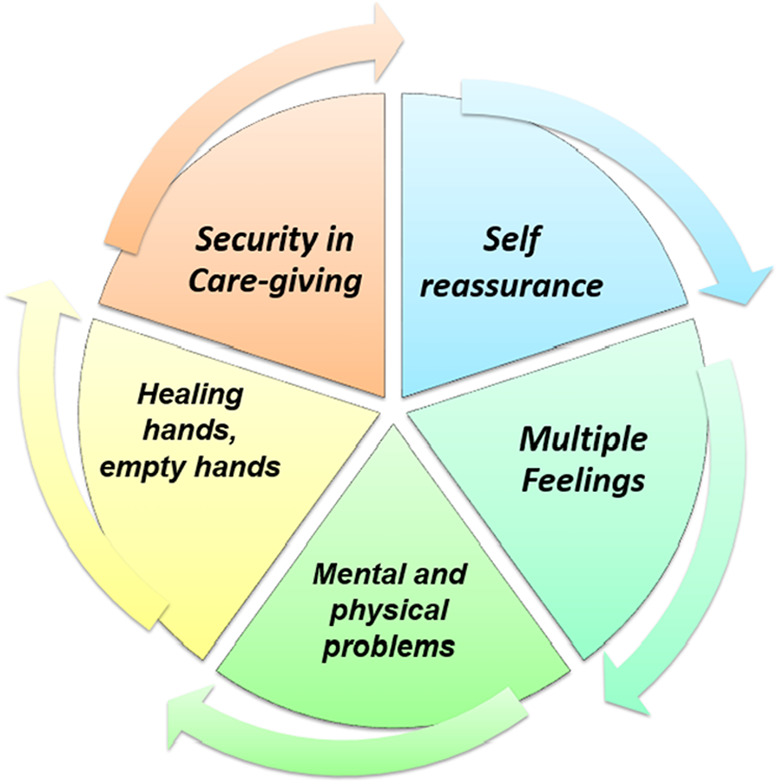

Data analysis of nurses’ experiences with respect to COVID-19 patients resulted in the extraction of information on 5 major categories: “security in care-giving,” “healing hands, empty hands,” “mental and physical problems,” “multiple feelings,” and “self-reassurance” and 11 subcategories.

Conclusion:

We found that giving care to COVID-19 patients entailed complex, intermingled, and interrelated physical, mental, and emotional aspects that underwent changes over time so that it can be called “journey of nursing in COVID-19 crisis.” The findings of this study further revealed that nurses’ experiences, feelings, and thoughts underwent modifications gradually, over time. They believed that they have undergone development in caregiving and experienced deeper aspects of nursing care.

Keywords: COVID-19, experience, content analysis, nurse, crisis

Introduction

In late December 2019, a group of patients with idiopathic pneumonia were reported to a local health care center. The etiologic cause of this idiosyncratic pneumonia was a novel coronavirus named Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (1). Coronavirus disease 2019 was declared a pandemic on March 11, and the disease has now spread to most countries (2). As of May 21, 2020, 4 893 186 patients had tested positive and confirmed for coronavirus disease, and 323 256 deaths have been reported in the world. But the exact number of patients remains unknown because asymptomatic cases or patients with very mild symptoms might not be tested and will not be identified (3). In March 2020, the first sample test was confirmed as positive for corona virus in Masih Daneshvari Hospital that is the reference center in Iran for all pulmonary and respiratory diseases (4).

The contagious nature of the condition demanded another coping strategy that served as a stubborn challenge for intensive care units (ICUs), physicians, and nurses (5). No specialized antivirus medication has been discovered yet to treat this condition. Hence, the management of these patients is based on supportive treatment. Since antiviral therapy is not available yet, giving care to these patients that are often involved in acute respiratory problems imposes a great workload on physicians and nurses, especially in pulmonary wards (6). Nursing care of patients with COVID-19 is very difficult and requires high standards and expert nurses (7).

Nurses are vital resources for every country. Their health and safety is very important not only for continuous and safe patient care but also for control of any outbreak and contagious diseases (8). However, providing care to COVID-19 patients has been a novel experience for nurses that in addition to increased workload may also cause stress and uncertainty (9). Some studies have paid attention to the psychological problems in nurses and the urgency of providing psychological care for them (10,11). However, no qualitative studies have been published about the experience of nurses in giving care to COVID-19 patients. Therefore, our study aims to understand and explored nurses’ experiences of nurses participating in nursing COVID-19 patients.

Methods

In this qualitative content analysis, purposive sampling method with maximal variability of the participants was used.

Setting and Participants

Participants included nurses, head nurses, and clinical supervisors employed in Masih-e Daneshvari Hospital affiliated to the Shahid Beheshti Medical University, Tehran, capital of Iran from February 20, 2019 to April 23, 2020. This hospital was the first reference center for COVID-19 patients. The inclusion criteria were holding a BSc, MSc, or PhD degree in nursing, history of at least 1-month work experience in caring for COVID-19 patients, and inclination for expressing experiences.

Data Collection

Data were collected through interviews and field notes. First, the researcher reached out to participants, to explain research goals and procedures, and to make an appointment for an interview if they were interested. Open questions with open-ended and interpretable answers were designed. Co-constructive questions were asked on the basis of participants’ responses to previous questions. The first question asked was “What’s your experience with giving care to COVID-19 patients?” The interview began with a general question and was co-constructed with participants’ replies. The items focused on determining nurses’ experiences with giving care to COVID-19 patients. The mean length of interviews varied from 30 minutes to 1 hour. All interviews were performed on the phone. Informed verbal consent was obtained from interviewing, voice recording, and data publication. The participants were assured that they could leave the study at any stage and information will be kept confidential. Taking detailed field notes was another method of data collection that was done at appropriate times. The participants were selected on the basis of interview analysis and data guidance.

To reach the theoretical saturation, 18 interviews were done with 18 participants and 5 field notes were taken; each interview was transcribed verbatim immediately after completion.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed with conventional content analysis (12,13). (Note1) In this method, data collection and analysis are done simultaneously. To do so, each interview was read several times, and the similar contents related to nurses’ experiences were placed in one text to form an analysis unit. Subsequently, semantic units were distilled from the participants’ expressions as primary codes. These codes were also minimized as far as possible on the basis of semantic and conceptual similarities and the summarized semantic units were extracted. The codes were placed in subcategories and similar subcategories were classified as one category. Finally, the latent meaning that was the covert content of the categories was placed in the categories/themes (12). The course of data reduction continued in all analysis units, categories, and subcategories. Ultimately, the data were contained in major categories that were more general and conceptual thence forming the themes. MAXQDATA10 was used in data analysis.

Rigor

Acceptability/confirmability of data was achieved through reviewing of the notes by the participants and by their complementary opinions and also via the researcher’s long-term involvement in the data. The findings were reviewed to make sure that they correspond to the participants’ experiences. Therefore, the extracted primary codes and categories were given to the participants to see whether they correspond to their experiences. Moreover, two expert faculty members, skilled in qualitative studies, supervised the research process. The research team made an attempt to record accurately all research stages and the decisions made so that other interested scholars may follow them up. To increase transferability, the method of selecting the participants, the culture governing them, and their characteristics were explained. Additionally, an attempt was made to increase the transferability through providing appropriate quotations in reporting the research (12).

Results

From February 20 to April 23, 1745 patients with COVID-19 were hospitalized in Masih Daneshvari Hospital. The polymerase chain reaction test showed that 1200 of them were definitely positive for corona virus. Of these, 196 passed away.

The participants (nurses) laid in the age range of 24 to 50 years with a mean age of 35.5 years. Of these, 6 were male and 12 females. The demographics of the participants are displayed in Table 1. The analysis of data on nurses’ experiences with giving care to COVID-19 patients led to the extraction of 5 main categories including “security in care-giving,” “healing hands, empty hands,” “mental and physical problems,” “multiple feelings,” and “self-reassurance” and 11 subcategories (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of the Participants.

| Characteristics of nurses | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 23-30 | 5 |

| 31-40 | 9 | |

| 41-50 | 4 | |

| Gender | Male | 6 |

| Female | 12 | |

| Position | Nurse | 12 |

| Head nurse | 4 | |

| Supervisor | 2 | |

| Work experience (year) | 10 -1 | 9 |

| 20-11 | 7 | |

| 30-21 | 2 | |

| Ward | ER | 2 |

| ICU | 5 | |

| Internal/pulmonology | 11 | |

| Academic degree | BS | 15 |

| MSc | 3 | |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Categories and Subcategories Extracted From Interviewing the Participants.

| Category | Subcategory | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Security in caregiving | - Occupational security - fear of infection - personal protective equipment. |

- “The virus is unknown. Suppose I am infected and then recover. What are the complications? What part of my body does it damage? My kidney, my lungs,…? It is not really clear.” (P. 1). - “I don’t eat or drink anything since morning when I come to work so that I may not need the toilet” (P. 4). - “I sweat heavily in these clothes; I get soaked. The face mask has injured my face. Breathing is difficult with them. It is difficult to work with this equipment, especially when we work with critically ill patients” (P. 11). One nurse stated in this regard: “I don’t take off this equipment even for one moment. I feel secure when I put on the isolation gown, mask, and face shield” (P. 16). - “I am afraid that I may lose my job if my lungs get affected by the disease; there is no treatment available; everything is in the trial and error phase. The future of the infected nurse is not clear” (P. 17). - “Every nurse that was infected was supported by the nursing office regarding meds, costs, and emotions. One of my tasks was to inquire about the infected nurses’ health status” (P. 5). |

| Healing hands, empty hands | - Lack of certainty - increased workload |

- “I come to work at the patient’s bedside with many questions in my mind: will this patient get well? Will a drug be discovered? (P. 10). - “Now that the treatments do not respond, I feel desperate. Everybody utters something. Even the WHO has changed its guidelines several times” (P. 8). - “The patient is fully lonely. They have nobody but me. Even their families are afraid of them. I sympathize with patients for their loneliness” (P. 7). |

| Mental and physical problems | - Mental problems - physical problems |

- “I can’t laugh even when I watch comic films. Sometimes, I want to cry deeply but I can’t. I can’t sleep at night without taking tranquilizers (she cries…)” (P. 14). - “Every day, I think I am infected. During these 50 days, I told myself 50 times that everything is finished, I am positive for COVID-19; still, I am not infected yet” (P. 13). - “My appetite has gone; I lost some pounds at the beginning; then, I returned to the previous state again” (P. 6). - “From now on, we think of the post-corona period. I know that my nurses were under great physical and mental pressure. I am going to ask an experienced psychiatrist to give consultation to them” (P. 5). |

| Multiple feelings | - Ethical hero - fear and hope |

- “Nurses have never been seen to this extend. We are now the heroes/heroines of the people. We should appear strong before their eyes. I believe that nurses can defeat COVID-19 with the help of patients” (P. 9). - “I went to the shop beside the hospital to buy something. The shop-keeper noticed that I work in the hospital and asked me to leave his shop quickly!!” (P. 2). - “I’m not afraid of my own infection. I’m a nurse and this is my job. I’m worried about my mother. I’m afraid that I might be a carrier and infect her. Something bad may happen to her; then, how can I live with the conscience torment?” (P. 3). |

| Self-reassurance | - Assurance - Recovery |

- “The WHO has announced pandemic; this means all the world are facing this challenge and all nurses around the world are involved. The feeling that you are not alone is a good one” (P. 18). - “Nurses were different in day 50 compared to day 1. The change was crystal-clear. There was much fear and anxiety among nurses in day 1. Now, nurses attend the patient’s bedside more comfortably” (P. 16). - “Nurses of day 1 were different from nurses of day 30; they were not fearful anymore and felt more comfortable; even their talking had changed” (P. 15). - “I thought I was doing a futile job. As the patients recovered gradually, I felt that the treatment was effective. This means that I had done my job successfully” (P. 1). - “During this time, I cleaned the whole house. Now, I am a real house-keeper; I cook and bake cakes to forget what has happened during those hours” (P. 14). |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

The main categories indicated a wide range of nurses’ experiences with giving care to COVID-19 patients as it named journey of nursing in COVID-19 crisis (Note3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Journey of nursing in COVID-19 crisis.

Security in Caregiving

Experiences of all nurses demonstrate that regardless of type of ward, work place, work experience, professional experience, and gender, “security in caregiving” was the most important category in caregiving for COVID-19 patients. This category consisted of the subcategories: “occupational security,” “fear of infection,” and “personal protective equipment.” All nurses were continually afraid of their infection with the disease as well as that of family and colleagues. All nurses had experienced the fear of death, fear of reinfection, fear of idiosyncratic complications after infection, fear of lack of support after infection, and fear of contamination/infection in the living environment and community. The nurses expressed that when they wear personal protective equipment, they ask themselves: Would this equipment provide sufficient protection? Some nurses were doubtful whether the personal protective equipment will be available to the end of the crisis. Can the hospital provide adequate amounts of these supplies? The great heat during wearing these clothes, the effect of mask and goggles on the nurses’ face, the feeling of being pressed, difficulty in walking and working while having personal protective equipment on, lack of fulfilling of physiological needs like urinating and defecating, and tolerating hunger and thirst were referred to by all nurses. On the other hand, the results of our study revealed that the nurses gained some confidence in their personal protective equipment after some weeks. They acquired the belief that they won’t catch the disease as long as they use this equipment correctly. Most nurses were concerned with changes in their behavior toward the infected patients, financial support after infection, continuation of insurance support, and continuation of their job in the case of complications after infection. They felt that their occupational security is jeopardized.

Healing Hands, Empty Hands

This category consists of the subcategories “lack of certainty” and “increased workload.” The experiences of all nurses demonstrated that they have been affected by lack of certainty and insolvency to varying degrees. Absence of a definitive cure, the obscure outcome of the current treatments, frequent changes of guidelines, and feelings of futile efforts by nurses were all effective in the created insolvency. Infection of a number of nurses, increasing number of critically ill patients; patients’ loneliness and their greater need for mental support besides physical support, exhaustion, isolation gown, and personal protective equipment; and consequently, nurses’ diminished efficiency all lead to nurses’ increased workload, increased physical contacts, and heavy pressure on their mind. Despite the help of voluntary forces, the nurses felt that their workload has increased and that they are highly exhausted.

Mental and Physical Problems

This category consisted of the subcategories “physical problems” and “mental problems.” The experiences of all nurses showed that they were mostly affected by mental problems such as inability to discharge their mind; inability to enjoy and laugh; feeling of crying spells; feeling of anger toward the disease and the present condition; feeling of loneliness, sleep disorders, and insomnia; feeling of depression, disappointment, and anxiety; feeling of tension and inclination for conflict and aggression; and feeling of shortness of breath, hypochondriasis, getting nostalgic for the family and ordinary days, the need for mourning, disturbance in communicating with the family and patients, and reduced threshold of tolerance. (Note2) Nurses’ physical problems were reduced appetite, profuse sweating, palpitation, irregular menses, tachycardia, tachypnea, constipation, facial rashes/acne, sweat burns, and nervous tics.

Multiple Feelings

This category consists of the subcategories “ethical hero” and “fear and hope.” The experiences of all nurses suggested that they have been converted to champions (heroes and heroines) due to the fact that they fight in the frontline of COVID-19 and due to the approach of people and media toward them, a hero that is morally obliged to resist failure even at the moments when they feel weak and fatigued. This feeling of the championship had both positive and negative aspects. The negative aspect entailed the feeling that champions may fade away after crisis, struggling for maintaining the position of the championship, creation of duty obligation by the community, and feeling of being sacrificed. The positive aspect was feeling of love for the profession, resisting the situation, and never giving up. Most nurses asserted that they have gained contradictory feelings. They could see themselves fluctuating between fear and hope. They were bothered by the hope for patients’ recovery and discovery of a definitive drug on one hand, and concern with patients’ death, increased length of crisis, and the following events, social seclusion, social stigma, rejection by colleagues, and concern with colleagues’ unawareness, on the other hand. Nurses with small children or elderly parents were worried more.

Self-Reassurance

This category consists of the subcategories “assurance” and “recovery.”

The nurses asserted that the main duty of nurses is caregiving. But support by family and coworkers, people and the charitable, higher order organizations, Ministry of Health, audio-visual mass media, journals, and being seen in the virtual space induced energy and feelings of value and thankfulness in them. Moreover, after WHO announced the pandemic state of the disease, nurses felt that they are not alone and that thousands of nurses round the globe are fighting the virus and giving care to these patients. Support by international organizations and other countries induced a better feeling in them. After some patients were discharged and nurses observed the patients’ recovery in the ward, the nurses felt that their performance has been effective. Indeed, they returned to themselves again and regained their self-confidence and professional performance. Nurses’ experiences indicated that they used some coping strategies to fight the created mental problems. Dancing, singing, phone communication, watching films, cooking, and praying helped nurses to maintain their high spirits and return to their previous feelings.

Discussion

The findings of this study further revealed that nurses’ experiences, feelings, and thoughts underwent modifications gradually, over time. They believed that they have undergone development in caregiving and experienced deeper aspects of nursing care. The feeling of insecurity at disease initiation changed by time passes. However, previous studies suggest that fear of transmission of infectious respiratory diseases exists in nurses (14,15). Nurse gained confidence in personal protective equipment during their exposure to COVID-19 and observed standard precautions and transmission-based precautions better than ever. Nurses’ experiences indicated that the use of this protective equipment bestows a feeling of security on nurses, leading to promoted caregiving for COVID-19 patients. Extensive provision of protective supplies was effective in creating a feeling of security in nurses. Some studies further suggest that inward wherein nurses routinely use the personal protective equipment their usage is obligatory, fewer nurses are affected by respiratory viruses (16,17).

Additionally, the provision of needs and all-inclusive mental and financial support of nurses infected with COVID-19, and returning to work after recovery, were also effective in creating feelings of security in nurses. After some time, the nurses were no longer afraid of COVID-19. Most nurses believed that fear of the virus had predisposed to care promotion and maturation. They also believed that all-inclusive support by the Ministry of Health, people, mass media, and nursing and hospital managers has been highly effective in this development. Fear of one’s infection and also family’s infection with the virus is common among nurses (18). Therefore, the health care authorities of a hospital or country and the management ought to support the staff during an epidemic, enabling them to overcome their fear (19). At first, the nurses believed that they should give care to patients with empty hands, and thus, feeling of uncertainty was annoying them. They first encountered an enormous global challenge and had a limited time to get familiar with this disease and method of caregiving for these patients. Lack of a definitive treatment and effective medicine, and frequent changes in caregiving and protective protocols, was disturbing, too. Lack of certainty in nursing can occur during diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and way of infection (9). Besides, the role of nurses in giving care to COVID-19 patients was complex and multilayered. This had led to nurses’ increased workload. They had to both give care to these patients and support the patients and their families both physically, mentally, and emotionally. Patients’ loneliness in the hospital and their unawareness of the manner of their infection caused nurses to have greater sympathy with patients. The sympathy created in nurses resulted in their better and more sympathetic care to meet all of their needs. Caring for infectious patients is a difficult task imposing a great workload of nurses (5). Nurses rendered the feelings they perceived as a turning point in their nursing experience and tried to reach a reciprocal understanding of their colleagues and patients. Indeed, while they were aware of the chance of infection with the virus, they supported the patient both mentally and spiritually. Singing, dancing, and playing music in the ward and talking to patients was an important part of giving care to these patients. Nurses’ experience showed that though nurses had many unpleasant memories of forgetting the champions, they rendered patients’ recovery and satisfaction with nursing services as the best reward for the nursing profession leading to nurses’ satisfaction. Studies have shown that nurses which caring patients with COVID-19 have greater risks of mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, and stress (20).

Despite many physical and mental problems created by giving care to these patients, most nurses tried to overcome these problems via the use of coping strategies. This experience had helped them to estimate the rate of their inducement and interest to continue the nursing profession. They were sure that they will participate again in such crises even with greater experience and enthusiasm. Anyway, this crisis in the health care system moved the physicians and nurses closer together. Nurses raced to give care to COVID-19 patients in the health care system. It made no difference whether that patient was a physician, a nurse, or other health care worker (9). Nursing managers also described their management in COVID-19 crisis as highly novel and complex. They believed that the nursing experience in the crisis was very constructive and has led to their development. They believed that they were concerned with the method of behaving nurses and physicians and managers’ crisis management after crisis more than frontline nurses; they were especially worried about forgetting these heroes after crisis. Hence, though they were combating the crisis, they were planning for the post–corona era. Crises like corona influence not only nurses but also their lifestyle and families (21). Another concern for nursing managers was the incidence of new, unknown crises and preparing nurses for such conditions (22). Presence of psychologists in the hospital, purchase of sports equipment, merrymaking factors, considering rewards for nurses, and offering off-days for them were among the recommendations offered by nursing managers to increase nurses’ coping skills in post–corona era. Nursing managers also recommended producing films, short clips, diary-writing, books, and pictures to be published in the virtual space to prevent fading away of these champions of corona frontline.

Conclusion

This study tried to show different aspects of caregiving for COVID-19 patients, an experience occurring for the first time globally and in Iran. The results of the study demonstrated that giving care to COVID-19 patients entailed complex, intermingled, and interrelated physical, mental, and emotional aspects that underwent changes over time so that it can be called “journey of nursing in COVID-19 crisis.”

Author propose that the health care systems of all countries train their staff rapidly at the time of disease outbreaks to be able to prevent any potential crisis. This preparedness may include holding training classes for nurses and other health care personnel, maneuvers of putting on personal protective equipment, forming crisis management teams, identifying all roles and responsibilities, and mental and spiritual preparedness of the health care team, especially nurses, to avoid crisis and surprising situations. This study was conducted in just one hospital, thus it is recommended that future studies involve more hospitals and the results be compared to our findings to maximally increase nurses’ knowledge of the disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the nurses in Masih-e Daneshvari Hospital affiliated to Shahid Beheshti Medical University in frontline of COVID-19.

Author Biographies

Fatemeh Monjazebi is a 10 years of experience in intensive care and heart transplantation, Instructor of Nursing Intensive Care, and PhD in Nursing.

Shirin Esmaeili dolabi is a 20 years of experience in intensive care and heart transplantation, Head of Nursing in Masih Daneshvari Hospital National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Neda Doozandeh Tabarestani is a 20 years of experience in intensive care and heart transplantation.

Gordafarid Moradian is a 20 years of experience in intensive care and heart transplantation.

Hamidreza Jamaati is a Chairman of Chronic Respiratory Diseases Research Center, National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (NRITLD), Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Maryam Peimani is a researcher of Diabetes research center, endocrinology and metabolism clinical sciences institute, Tehran university of medical sciences.

Notes

Conventional content analysis is one type of latent analysis, and in these type of analysis the meaning units classify in sub categories and categories (12).

Mental problems were inability to discharge their mind, inability to enjoy and laugh, feeling of crying spells, feeling of anger toward the disease and the present condition, feeling of loneliness, sleep disorders and insomnia, feeling of depression, disappointment, and anxiety, feeling of tension and inclination for conflict and aggression, feeling of shortness of breath, hypochondriasis, getting nostalgic for the family and ordinary days, the need for mourning, disturbance in communicating with the family and patients, and reduced threshold of tolerance.

Brief description of figure is in the main manuscript: The main categories indicated a wide range of nurses’ experiences with giving care to COVID-19 patients as it named Journey of Nursing in COVID-19 Crisis.

Authors’ Note: All authors have been correspondence to collecting and analyzing data. All authors have written the first draft of manuscript and approved the final version. The study proposal was approved by Ethic Committee of Shahid Beheshti Medical University with code of ethics no: IR.SBMU.NRITLD.REC.1399.066 and research code no: 22955 dated 16.4.2020. This study was distilled from a research project at Shahid Beheshti Medical University with research code no: 22955.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by funding from Chronic Respiratory Diseases Research Center, National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The funding source had no involvement in preparation of the article, study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

ORCID iD: Fatemeh Monjazebi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8311-0296

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8311-0296

References

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation Report—122. World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed 21 May 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jamaati H, Dastan F, Dolabinjad SE, Varahram M, Reza Hashemian SM, Rayeini SN, et al. COVID-19 in Iran: a model for crisis management and current experience. Iran J Pharm Res. 2020;19:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun N, Wei L, Shi S, Jiao D, Song R, Ma L, et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Members WC, Wang H, Zeng T, Wu X, Sun H. Holistic care for patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019: an expert consensus. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7:128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang D, Xu H, Rebaza A, Sharma L, Cruz CSD. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo Q, Wang XQ, Liu S, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e790–e798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:228–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koh Y, Hegney D, Drury V. Nurses’ perceptions of risk from emerging respiratory infectious diseases: a Singapore study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2012;18:195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Al Knawy BA, Al-Kadri HM, Elbarbary M, Arabi Y, Balkhy HH, Clark A. Perceptions of postoutbreak management by management and healthcare workers of a Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in a tertiary care hospital: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e017476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, Ko SM, Qian F, Ng V, et al. Risk perception and impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore what can we learn? Med Care. 2005;43:676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gan WH, Lim JW, David KO. Preventing intra-hospital infection and transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare workers. Saf Health Work. 2020;11:241–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;27:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rana W, Mukhtar S, Mukhtar S. Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e17–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:2133–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuteifan K, Pasquier P, Meyer C, Escarment J, Theissen O. The outbreak of COVID-19 in Mulhouse: hospital crisis management and deployment of military hospital during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Mulhouse, France. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]