Abstract

Dignity therapy as an intervention has been used for individuals receiving palliative care. The goal of this review is to explore the current state of empirical support to its use for end-of-life care patients. Data sources were articles extracted from search engines PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. The years searched were 2009 to 2019 (10-year period). The review process was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Results revealed the feasibility, acceptability, satisfaction, and effectiveness of dignity therapy for life-limiting cases/conditions of patients in different age groups. It also highlighted the importance of the therapy setting and the need to apply this in the cultural context. The meaning of dignity therapy to patients and their family care members also emerged. Findings showed most patients displayed the need to leave a legacy and from this their core values surfaced. In conclusion, this review highlighted the contribution of dignity therapy to the holistic care of patients who hope to leave a legacy. The therapy was also relevant to decrease the anxiety; depression, and burden of family members throughout the palliative care period of their loved ones.

Keywords: dignity, dignity therapy, end-of-life care, palliative care

Background/ Introduction

Dignity therapy was first developed as a way to assist patients in dealing with the approach to end of life (1). This intervention helped to conserve the dying patient’s dignity by addressing the sources of psychosocial and existential distress. It gave patients a chance to record the meaningful aspects of their lives and leave behind what can benefit loved ones in the future (2). It has relieved psychological and existential distress in patients by using life review as a form of psychotherapy (3).

The relevance of dignity therapy was grounded in the dying patients’ self-reported notions of dignity. It is used to addresses their need to feel that life has had meaning and to leave a sense of self to remain with loved ones beyond their own life. It helped patients to get in touch with accomplishments and experiences that made them unique and valued as human beings (2). Dignity therapy showed promise as a novel therapeutic intervention for suffering and distress at the end of life (1).

Dignity therapy was developed for use among individuals who are near death (4). Patients are asked to write a formal written narrative of their life to the person they choose. The therapeutic part was when the patient would be asked a series of questions about parts of their life that they remember the most and are most important about their life story. Answers to this were transcribed and returned to them for editing, going back and forth with the therapist for a polished documented result. This result can be given to their significant others, family, and friends. With the end goal of alleviating end-of-life suffering, dignity therapy has focused on crafting a person’s legacy by documenting important memories and writing messages for their loved ones to read. However, there was little known about its effect on the family members reading it (3).

The purpose of this literature review was to provide evidence-based information on the effect of dignity therapy as an intervention. The goal was to evaluate the current empirical support to its use for end-of-life care patients. This is congruent with the need to develop and utilize therapeutic interventions that support hopefulness, sense of meaning, and dignity, in order to alleviate psychosocial and existential distress in end-of-life care patients (5).

Methods

A literature review was conducted with the assistance of a medical librarian who refined the terms using search strategies. The key words identified were dignity therapy, terminal care, hospice care, palliative care, hospice and palliative care nursing, palliative medicine, end of life, and terminal illness. MESH terms were also included in the search.

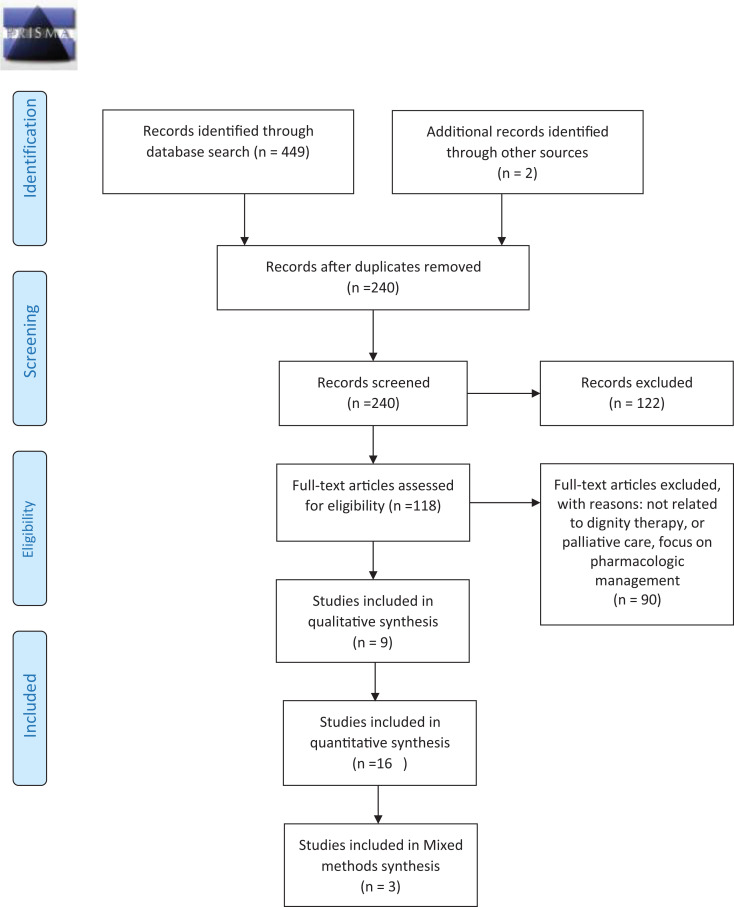

Databases searched were PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Articles were included if published within the past 10 years (2009-2019). The authors of the review identified the managing criteria for abstract screening and full-text review. The inclusion criteria were dignity therapy in end-of-life care, palliative care, hospice care, and terminal care across all age groups. The exclusion criteria were other therapeutic interventions and pharmacologic management for palliative, terminal, hospice and end-of-life care, and all systematic reviews on the topic. A total of 451 articles were identified for review. Title and abstract screening were conducted, followed by full-text review, and final lists of 28 were included. Articles were reviewed as guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 2009 framework (Figure 1) (6).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 2009 flow diagram.

Results

The review showed very extensive studies on the feasibility, acceptability, satisfaction, relevance, and effectiveness of dignity therapy that were conducted from 2009 to 2019 among end-of-life care patients. There were 28 publications included in this review that was further classified into 16 quantitative, 9 qualitative, and 3 mixed-method studies. The reviews were conducted primarily in Western countries, including the United States, Australia, and Canada. There were very few studies conducted in Asia, which only included Japan (7) and Taiwan (8).

In the quantitative studies, many used the pretest and post-test intervention design (1,5,9,10 –12); while the qualitative literature used a case study (13) and grounded theory (14) design.

Four of the studies used the protocol of Chochinov (13,15 –17). As cited by Andreis et al (13), the Chochinov protocol was used primarily with people who were terminally ill. It consists of a short-term psychotherapy intervention that includes 3 major aspects: the physical aspects related to the disease and symptoms, existential/spiritual aspects based on the patient’s life history, and the social relationships aspect linked to the quality of the relationship between the patient, practitioners, and family members.

Feasibility, Acceptability, and Satisfaction

Feasibility, acceptability, and satisfaction of patients and family caregivers to dignity therapy were usually assessed by completing a self-report questionnaire or participant feedback questionnaire. Many of the studies reported high acceptability and satisfaction to dignity therapy (9 –12,18,19).

Effectiveness

Effectiveness of dignity therapy were measured using the Patient Dignity Inventory to assess dignity-related distress, Herth Hope Index for hopefulness, and FACIT sp 12 for spiritual well-being (9,11). While for family caregivers, assessment of burden used were Zarit Burden Interview, Herth Hope Index for hopefulness, and HADS for anxiety and depression (9).

Meaning to Patients

For patients, dignity therapy promotes self-expression, connection with loved once, sense of dignity, purpose, and continuity/improved sense of self; strengthens identity (1,10,11,13,20); and increases hopefulness and dignity (1,11,15,21) and spirituality (20). Most importantly, dignity therapy decreases distress symptoms such as depression, desire for death, or suicidal thoughts (4,22). One study stated that dignity therapy promotes self- expression, connection with loved ones, sense of purpose, and continuity of self (20).

Legacy Project

Specifically, the development or creation of a legacy project, also called “generativity” documents (22), promotes independent reflection, autonomy, and opportunities for family interaction, which can lead to better relationships (11,13,20) and helping to address unfinished business (9,10). The generativity document provides a safe therapeutic environment that can deliver a detailed message to family members and caregivers to facilitate early palliative care, thus allowing the patient to reappraise aspects of their lives positively and enjoy the opportunities to reminisce (19). Through this, the core values of the patient become apparent (14). A patient who has developed the generativity documents can promote independent reflection, autonomy, and opportunities for family interaction during the review and discussion of the project (20).

To accomplish this, Dose et al (22) asked patients to produce a generativity document, which the patient can later share with their family. The document can also be made into a form of a life plan, which is a type of “bucket list” wherein the patient document future hopes and dreams.

Core Values

The core values identified in the various studies were (1) family (1,11,20), (2) autonomy (7,9,10,20), (3) sense of self or sense of identity (9 –11,13,20), (4) spirituality (5,15,21), (5) hopefulness (5), (6) acceptance (11), and (7) sense of purpose or meaning (1,22) in life.

Meaning to Family Care Members

Dignity therapy was reported as a source of comfort for family care members during bereavement (9 –11,23). Furthermore, the therapy decreased the burden, anxiety, and depression among family members and even increased their hopefulness (5,11) for their loved ones. Some family care members believed that a dignity therapy document would be a comfort during their time of bereavement (10).

Cases and Age groups

Most of the studies observed middle and older adults with advanced cancer and motor neurone disease (MND), but Newman (24) completed a study on the efficacy of dignity therapy to patients who need allogenic bone marrow transplant (BMT) and Rodriguez (25) has assessed the benefits of dignity therapy to a group of adolescents with advanced cancer. Similarly, to other studies, dignity therapy was found to be beneficial to patients with BMT in reducing existential distress after transplantation (24). The adolescent group with advanced cancer reported similar responses. However, their main concern was being worried about death and dying. According to them, they need to identify to whom and in which way they can verbalize their worries (25).

Table 1.

The literature reviews for Dignity Therapy.

| Author(s) | Title | Design and methodology | Population/demographics | Therapy process | Primary outcomes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akechi et al 7 | Dignity therapy: preliminary cross-cultural findings regarding implementation among Japanese advanced cancer patients | Survey | n = 11 | Chochinov | Terminally ill cancer patients who wish that they were unaware of their impending death may be less likely to participate in DT. Their aversion to participating in the study may not have been due to the DT per se, but rather, their having been confronted with information that they did not wish to hear.a | Although DT should not be routinely recommended to all terminally ill Japanese cancer patients, this therapy may be promising for patients who hope to leave a legacy. |

| Andreis et al 13 | Dignity therapy: A new psychotherapeutic approach for people facing advanced disease | Case study | 4 patients | The interview uses 10 core questions, and the responses are used to create a written legacy document. | DT showed to be a new promising therapeutic intervention for suffering and distress at the end of life. The literature review finds robust evidence for DT’s overwhelming acceptability, rare for any medical intervention, especially in psychosocial-spiritual care. | The DT is a multidimensional psychosocial intervention for patient-centered care, and it depends on experiences of generativity and the pursuit of purpose and meaning. |

| Aoun et al 9 | Dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease and their family caregivers: a feasibility study | Repeated-measures design preintervention and postintervention. | 27 patients and 18 family and caregivers | Patients are invited to discuss issues that they would most want remembered about their life. | This is the first DT study to focus on MND and on home-based caregiving. The therapy needs to be offered earlier. | Results established the importance of narrative and generatively for patients with MND and may open the door for other neurodegenerative conditions. |

| Beck et al 20 | Abbreviated dignity therapy for adults with advanced-stage cancer and their family caregivers: qualitative analysis of a pilot study | Qualitative | Interview with 11 participants | The legacy projects were coded for expression of core values. | Suggest that abbreviated DT effectively promotes 1 self-expression, 2 connection with loved ones, 3 sense of purpose, and 4 continuity of self.a | Direct content analysis was used to assess feedback from the interviews about benefits, barriers, and recommendations regarding abbreviated DT. |

| Bentley et al 5 | Is dignity therapy feasible to enhance the end of life experience for people with motor neurone disease and their family carers? | Cross-sectional study utilizing a single-treatment group and a pre-/post-test design. | 50 people diagnosed with MND and their nominated family carers. | Outcomes for participants include hopefulness, spirituality, and dignity. | Outcomes for family carers include perceived caregiver burden, hopefulness, and anxiety/depression. | Suggest the need to develop and utilize interventions that will support hopefulness, a sense of meaning, and dignity in order to alleviate psychosocial and existential distress in persons with MNDa |

| Bentley et al 10 | Dignity therapy: a psychotherapeutic intervention to enhance the end of life experience for people with motor neurone disease and their family carers | A pre–post design | 26 people with MND and 17 family carers | Mild cognitive decline and pseudobulbar affect were found to have minimal impact on the acceptability/feasibility of the psychotherapy. | DT was beneficial to people with MND, especially in the areas of encouraging acceptance (70%), strengthening identity (70%), helping to address unfinished business (65%), and helping to feel they could still play an important role (65%).a Acceptability was high, with 84% reporting the therapy was helpful to them and 92% reporting the therapy was satisfactory. Acceptability was also high with family carers, with 94% finding it helpful to their family member and 75% recommending it to others.a | Low base rates of distress precluded being able to demonstrate significant postintervention differences on measures of distress. |

| Bentley et al 11 | Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for family carers of people with motor neurone disease | Cross-sectional study utilizing a 1-group pretest and post-test design | 18 family carers of people diagnosed with MND | Examining family carers’ involvement in the therapy. | There were no significant pretest and post-test changes on the group level, but there were decreases in anxiety and depression on the individual level.a. | DT is not likely to alleviate caregiver burden in MND family carers, but it may have the ability to decrease or moderate anxiety and depression in distressed MND family carers. |

| Bentley et al | Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease | Cross-sectional feasibility study using a 1-group pretest and post-test design | 29 people diagnosed with MND | Examining the length of time taken to complete DT | There were no significant pretest and post-test changes for hopefulness, spirituality, or dignity on the group level, but there were changes in hopefulness on the individual.a | DT for people with MND is feasible and acceptable. Further research is warranted to explore its ability to diminish distress. |

| Bernat et al 18 | Piloting an abbreviated dignity therapy intervention using a legacy-building web portal for adults with terminal cancer: a feasibility and acceptability study | A pilot legacy-building intervention | 16 participants enrolled in the study (12 females, 4 males). | This differed from traditional DT in 3 ways as mentioned. | Participant satisfaction was high with the intervention (mean = 8.82, SD = 1.08) and the final legacy project they created (mean = 8.55, SD = 1.13). Although the interventionist trained all participants in use of the web portal, fewer than half (45%) of the participants reported using it to complete their legacy project; the majority used a word processing program.a | Results suggest that our legacy-building intervention was both feasible and mostly acceptable. |

| Brozek et al 15 a | Dignity Therapy as an aid to coping for COPD patients at their end-of-life stage | Survey | 10 patients with severe COPD | DT intervention was implemented according to the protocol established by Chochinov et al | Satisfaction questionnaire showed a positive effect of DT on the patient’ well-being.a

The analyses of the patients’ original statements enabled an effective identification of the spiritual suffering and spiritual resources and faced by COPD patients.a |

Conclusion: DT is an intervention well received by COPD patients, which may help them in recognizing and fulfilling their spiritual needs in the last phase of their life. |

| Chochinov et al 1 | Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life | Correlational pretest and post-test design. | Terminally ill inpatients | DT invites patients to discuss issues that matter most or that they would most want remembered | 91% of participants reported being satisfied with DT; 76% reported a heightened sense of dignity; 68% reported an increased sense of purpose; 67% reported a heightened sense of meaning; 47% reported an increased will to live; and 81% reported that it had been or would be of help to their family.a | DT shows promise as a novel therapeutic intervention for suffering and distress at the end of life. |

| Chochinov et al 4 | Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial | RCT | 165 of 441 patients were assigned to DT | DT is an individualized, short-term psychotherapy | No significant differences were noted in the distress levels before and after completion of the study in the 3 groups.a | Secondary outcomes of self-reported end-of-life experiences were assessed in a survey that was undertaken after the completion of the study. |

| Dose et al 22 | Dignity therapy feasibility for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy | Feasibility study | N = 10 | DT is a brief psychotherapeutic intervention consisting of a focused LR. | Two-thirds were satisfied/very satisfied with DT/LP, and 78% found study participation worthwhile and DT/LP timing to be just right, and they would recommend DT/LP to others. QoL improved (baseline mean = 7.0; T2 = 7.25). Distress scores improved (baseline mean = 6.13; T2 = 5.63).a | Implications for research, policy, or practice. Conducting DT/LP in an outpatient oncology chemotherapy setting for newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients is both feasible and acceptable. |

| Dose et al | Outcomes of a dignity therapy/life plan intervention for patients with advanced cancer undergoing chemotherapy | Intervention study | N = 18 patients | DT entailed interviews during 3 outpatients | No variables were significantly different from baseline to postintervention and 3 months later, except for less distress between baseline and 3 months (P = .04).a | Participants documented life goals as their life plan. |

| Flad et al 26 | Dignity therapy at an Austrian acute care hospital: feasibility and acceptance on wards that are not specialised in palliative care | Mixed-method study | N = 10 | Conducting DT on wards | As patients usually spend only a very short time in hospital, professionals are put under pressure to conduct DT immediately and quickly.a | DT represents an appreciated and valuable contribution to a holistic care of patients with palliative care needs in an acute care hospital under the condition of open communication about the life-limiting character of the disease. |

| Gagnon et al 19 | Dignity therapy: an intervention to diminish psychological distress in palliative care patients | Intervention study | N = 33 | DT | Results confirmed the relevance of this intervention and showed that it is associated with a high level of satisfaction for participants and family members. | |

| Goddard et al 23 | Dignity therapy for older people in care homes: a qualitative study of the views of residents and recipients of ‘generativity’ documents | Qualitative exploration | N = 14 | Framework approach | Four categories are reported: views on the document, impact on residents, impact on family, and potential impact on care homes.a | Family members felt DT had helped them. Findings suggest that DT may be useful for enhancing the end-of-life experience for residents and families |

| Hack et al 14 | Learning from dying patients during their final days: life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy | Qualitative study Grounded theory approach | 100 terminally ill patients | DT is a transcript of the edited therapy session(s). | The transcripts revealed that DT serves to provide a safe, therapeutic environment for patients to review the most meaningful aspects of their lives in such a manner that their core values become apparent. | The findings are discussed in terms of values theory, the role of DT, and consideration of values clarification in clinicians’ efforts to enhance the dignity of terminally ill patients. |

| Łabuś-Centek et al 16 | Application of dignity therapy in an advanced cancer patient — wider therapeutic implication | Mixed methods | An advanced cancer patient within a Polish hospital setting | MH. Chochinov’s DT protocol was applied. | The survey questionnaire indicated that by far the greatest benefit consisted in an overall improvement of his mental well-being (4.67). Benefits for the family followed 4 , including his hope for recovering family ties 4 . An unexpected therapeutic effect consisted in re-establishing a broken relationship with his daughters. | The patient was also asked to complete a survey questionnaire designed to assess the therapeutic effectiveness of DT in the intervention. |

| Lee et al | Envoy service, a form of dignity therapy, to assist to express personal values and communication with family members and caregivers: a preliminary report | Case studies | The study has 10 patient’s experiences. | “Envoy service” was to deliver a detailed message to family members | “Envoy service” could be valuable for patients with incurable disease to help to express regarding their personal life values and communication in end-of-life options between the patients, family members and caregivers and might help to facilitate early palliative care.a | The assigned patients were helped by trained dialogist to express in narrative form regarding the personal values and end-of-life care options. |

| Li et al 27 | Conceptualizations of dignity at the end of life: exploring theoretical and cultural congruence with dignity therapy | Qualitative exploration | N = 9 | DT—a novel nurse-delivered psychotherapeutic intervention | Being a valuable person is the core meaning of patients’ dignity and this comprises intrinsic characteristics and extrinsic factors.a | The concept of dignity is culturally bound and understood differently in the Chinese and Western context; such differences should be considered when planning and delivering care. |

| Newman 24 | Efficacy of dignity therapy for allogeneic bone marrow transplant patients: A qualitative pilot study | Mixed methods | 5 patients | DT is a brief empirically validated psychotherapy. | The DT intervention appears to be a feasible, relevant, and meaningful intervention to this novel, nonterminally ill patient population.a | 3 visits; consent documents were signed at the first; the DT interview was conducted at the second, which was then transcribed and edited. |

| Rodriguez 25 | Assessing the benefit of dignity therapy for adolescents with advanced cancer: a prospective explorative mixed-method study | A small-scale open-label RCT | Adolescents with advanced cancer | Qualitative interviews with participants and family members | The findings of my research to date are suggestive that children have similar responses and worries about death and dying to adult populations, but they struggle to decide who to verbalize these worries to. Currently, there is no shared intervention for this purpose with children.a | Family members will also be asked to reflect on the benefits of the therapy 3 months after bereavement. |

| Tait et al | Meaning and legacy in the terminally-ill elderly: dignity therapy and its impact on patients and health professionals | Qualitative interviews | Dignity interviews were administered to 12 elderly patients by residents. | Medical residents were taught to utilize DT | From a developmental perspective, a dying elderly patient’s meaning and legacy making, often in the form of imparting wisdom, may solidify navigation through Erikson’s final and socially contextualized stage of Ego-Integrity vs Despair in a preparatory life-completion process.a | DT is a single 1-hour session intervention that provides patients an opportunity to make meaning out of life and impending death and to solidify a sense of integrity by using one’s individual agency to create a legacy that bears one’s addressees in mind. |

| Testoni et al 17 | Dignity as wisdom at the end of life: sacrifice as value emerging from a qualitative analysis of generativity documents | Qualitative thematic analysis | 5 patients in end-of-life and palliative care | Chochinov protocol using Schwartz’s matrix of values. | The results showed the role of values in the construction of wisdom and confirmed the importance of family relationships. The value of sacrifice, which is supported by various religious traditions, emerged as a perceived factor, indicating personal wisdom.a | The implications, not only for end-of-life counseling but also for other fields and disciplines focusing on spiritual care, in particular for pastoral psychology, are significant. |

| Vergo et al 12 | A feasibility study of dignity therapy in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer actively receiving second-line chemotherapy | Pretest/post-test design. | 15 of 17 patients | DT early in the disease trajectory | Most of the patients who completed DT reported being satisfied and felt it was helpful, that it increased their sense of meaning, that it would be helpful to their family, and that it increased their sense of dignity, their sense of purpose, and their will to live.a

|

Conclusion: DT is a highly feasible, satisfying, and meaningful intervention for advanced colorectal cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapy earlier in the course of their and may result in an understanding of disease and goals of care at the end of life. |

| Vuksanovic et al | Dignity therapy and life review for palliative care patients: a randomized controlled trial | Evaluation | 70 adults with advanced terminal disease | DT shows evidence of acceptability and utility in palliative care setting | There were no significant changes for dignity-related distress or physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being among the 3 groups.a | Primary outcome measures were the Brief Generativity and Ego-Integrity Questionnaire, Patient Dignity Inventory, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, version 4, and treatment evaluation questionnaires. |

| Vuksanovic et al 28 | Dignity therapy and life review for palliative care patients: a qualitative study | Qualitative | 56 participants | Context DT | Themes of spirituality, illness impacts, and unfinished business were relatively less common in WDT participants.a | Conclusion: This study provides further insight into what palliative care patients consider to be most important and meaningful to them when taking part in DT and LR. |

| Extracted studies: 28 | Quantitative: 16 Qualitative: 9 Mixed methods: 3 Total 28 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DT, digital therapy; MND, motor neurone disease; RCT, randomized controlled trial; LP, lumbar puncture; LR, life review; QoL, quality of life; WDT, waitlist DT.

aThe number of reviewed literatures in Table 1 per research category.

Therapy Setting

Dignity therapy was commonly done at home and given by someone who specializes in palliative care. However, one study explored the use of an acute care hospital in Austria for the feasibility and acceptance of dignity therapy (26). This study met a major challenge in identifying a target group, since the patients spent a very short time in the hospital. The study necessitated an immediate and quick conduction of the therapy. As a result, the notable observation was to realize that dignity therapy conducted within a short amount of time requires a sufficient number of human resources to be successful (26).

Cultural Context

Dignity therapy’s theoretical and cultural congruence has also been explored in literatures (8). There was a study that concluded the concept of dignity as culturally bound and understood differently in the Asian culture compared to the Western context. From an Asian cultural perspective, a person’s value was the core meaning of their dignity and a dynamics relationship exists between extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Similarly, another study (7) suggested that there was an underlying difference regarding the general attitude of a person toward a “good death” between the Western and Japanese culture. Thus, this difference in perspectives may influence a lower participation rate to dignity therapy in Japan.

Limitations

The review was limited to the use of dignity therapy among end-of life care patients. Other therapies in combination to this were not included. The pharmacodynamics of the patients was also not included in the review. Similar studies and systematic reviews were excluded in this project.

The patient’s gender did not emerge as a factor for consideration in doing dignity therapy. There was also no mention of negative consequences that arise from its use.

Conclusions

Dignity therapy represents an appreciated and valuable contribution to holistic care of patients with palliative care needs. Even in acute care hospitals under the condition of open communication, the therapy can also address the life-limiting characteristics of a disease (26). Therapy outcomes are encouraging, beneficial, and effective in enhancing the end-of-life experience for patients who hope to leave a legacy.

For family care members, dignity therapy was essential to decrease anxiety, depression, and burden associated with end-of-life care. It was suggested that dignity therapy could influence various important aspects of the end-of-life experience for the family (9), including helping patients attend to unfinished business and make them feel like they were still themselves (11).

Dignity therapy was used for patients in different age groups with terminal illness, such as cases of advanced cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other neurodegenerative conditions including BMT patients in a home-based setting. However, for dignity therapy to be meaningful and relevant, it is essential to provide adequate time when conducting sessions.

The factors to consider in implementing and delivering effective dignity therapy were (1) differences in general attitude toward good death, especially those patients who deny the impending death (7); (2) information on patients resources and spiritual challenges (15); (3) the importance of family ad autonomy to patients (20); and (4) mild cognitive decline and pseudobulbar effect to patients with MND (10,11). Nurses in delivering dignity therapy to end-of-life care patients must consider these factors.

Cultural differences were considered when planning and delivering dignity therapy (27). The meaning of dignity to end-of-life patients from different countries was considered to be culture based. One example demonstrated that “unawareness of death” was a relevant concept of good death in Japan (7).

The study by Akechi et al (7) suggested that terminally ill cancer patients in Japan may try to cope with their terminal condition by denying their impending death, and this must be noted upon assessment. Additionally, the importance that patients place on family should not be underestimated. Nurses caring for end-of-life patients should honor their autonomy (20). The nurse as a dignity therapist may provide a better experience for the family members when they are aware of acceptance levels and quality of partner relationships (11). Nurses must offer ongoing psychosocial support to patients with life-limiting diseases. This is a way to identify suitable dignity therapy participants and to know the right moment to offer it to patients (26).

Since the review attested to the effectiveness of dignity therapy, it was suggested that this brief psychotherapeutic intervention be tested on future larger trials (12). Although dignity therapy may be bound with cultural considerations, this therapy was promising for patients who hope to leave a legacy (7). Dignity therapy could fill in a gap and provide a possible solution to psychosocial distress at the end of life, an area of palliative care widely acknowledged as in need of improvement (5).

Author Biographies

Pearl Ed Cuevas, PhD, MAN, RN, FGNLA, is an associate professor at Centro Escolar University Manila. She was International Visiting Scholar at Johns Hopkins, School of Nursing in 2019 and was distinguished educator in Gerontology Nursing Nursing by the National Hartford Center for Gerontological Nursing Excellence in 2020.

Patricia Davidson, PhD, MEd, RN, FAAN, is the dean of the Johns Hopkins University, School of Nursing. She is one of the most influential nursing leaders in the United States. She mentored the first author as an international visiting scholar at Johns Hopkins.

Joylyn Mejilla, MAN, RN, is a faculty of Centro Escolar University, Manila. She is also the assistant to the dean for Curriculum and Supervision at the School of Nursing.

Tamar Rodney, PhD, RN, PMHNP-BC, CNE, is a faculty of the Johns Hopkins University, School of Nursing. She is an experienced researcher and a psychiatric-mental health specialist.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Pearl Ed Cuevas, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2574-2222

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2574-2222

References

- 1. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5520–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dignity in Care. Toolkit. 2016, Updated June 22, 2020. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://dignityincare.ca/en/toolkit.html

- 3. Martínez M, Arantzamendi M, Belar A, Carrasco JM, Carvajal A, Rullán M. et al. ‘Dignity therapy’, a promising intervention in palliative care: a comprehensive systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2017;31:492–509. doi:10.1177/0269216316665562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T. et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:753–62. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bentley B, Aoun SM, O’Connor M, Breen LJ, Chochinov HM. Is dignity therapy feasible to enhance the end of life experience for people with motor neurone disease and their family carers? BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-11-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Akechi T, Akazawa T, Komori Y, Morita T, Otani H, Shinjo T. et al. Dignity therapy: preliminary cross-cultural findings regarding implementation among Japanese advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2012;26:768–9. doi:10.1177/0269216312437214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li H, Armes J, Richardson A. An investigation of terminally ill Taiwanese patients’ and palliative care professionals’ perspectives on dignity: a preliminary study for conducting dignity therapy in Taiwan. Palliat Med. 2010;24:S212. doi:10.1177/0269216310366390 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aoun S, Chochinov H, Kristjanson L. Dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease and their family caregivers: a feasibility study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15:90. doi:10.3109/21678421.2014.960176/064 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bentley B, Aoun S, O’Connor M, Breen LJ, Chochinov HM. Dignity therapy: a psychotherapeutic intervention to enhance the end of life experience for people with motor neurone disease and their family carers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:13–4. doi:10.3109/21678421.2013.838413/023 22642305 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bentley B, O’Connor M, Breen LJ, Kane R. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for family carers of people with motor neurone disease. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-13-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vergo MT, Nimeiri H, Mulcahy M, Benson A, Emmanuel L. A feasibility study of dignity therapy in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer actively receiving second-line chemotherapy. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12:446–53. doi:10.12788/jcso.0096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andreis F, Gadaldi E, Meriggi F, Mirandola M, Rota L, Abeniet C. et al. Dignity therapy: a new psychotherapeutic approach for people facing advanced disease. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:vi86. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx434 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hack TF, McClement SE, Chochinov HM, Cann BJ, Hassard TH, Kristjanson LJ. et al. Learning from dying patients during their final days: life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliat Med. 2010;24:715–23. doi:10.1177/0269216310373164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brozek B, Fopka-Kowalczyk M, Labus-Centek M, Damps-Konstańska I, Ratajska A, Jassem E. et al. Dignity therapy as an aid to coping for COPD patients at their end-of-life stage. Adv Respir Med. 2019;87:135–45. doi:10.5603/ARM.a2019.0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Łabuś-Centek M, Adamczyk A, Jagielska A, Brożek B, Graczyk M, Larkin P. et al. Application of dignity therapy in an advanced cancer patient — wider therapeutic implications. Medycyna Paliatywna W Praktyce. 2019;12:218–23. doi:10.5603/PMPI.2018.0015 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Testoni I, Bingaman KA, D’Iapico G, Marinoni GL, Zamperini A, Grassi L. et al. Dignity as wisdom at the end of life: sacrifice as value emerging from a qualitative analysis of generativity documents. Pastoral Psychol. 2019;68:479–89. doi:10.1007/s11089-019-00870-9 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bernat JK, Helft PR, Wilhelm LR, Hook NE, Brown LF, Althouse SK. et al. Piloting an abbreviated dignity therapy intervention using a legacy-building web portal for adults with terminal cancer: a feasibility and acceptability study. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1823–5. doi:10.1002/pon.3790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gagnon P, Chochinov HM, Cochrane J, Le Moignan Moreau J, Fontaine R, Croteau L. Psychothérapie de la dignité: Une intervention pour réduire la détresse psychologique chez les personnes en soins palliatifs [Dignity therapy: an intervention to diminish psychological distress in palliative care patients]. Psycho-Oncologie. 2010;4:169–75. doi:10.1007/s11839-010-0267-1 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beck A, Cottingham AH, Stutz PV, Stutz PV, Gruber R, Bernat JK. et al. Abbreviated dignity therapy for adults with advanced-stage cancer and their family caregivers: qualitative analysis of a pilot study. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17:262–8. doi:10.1017/S1478951518000482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dose AM, Rhudy LM. Perspectives of newly diagnosed advanced cancer patients receiving dignity therapy during cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:187–95. doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3833-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dose A, Hubbard J, Sloan J, McCabe P. Dignity therapy feasibility for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:425–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goddard C, Speck P, Martin P, Hall S. Dignity therapy for older people in care homes: a qualitative study of the views of residents and recipients of ‘generativity’ documents. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:122–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Newman E. Efficacy of dignity therapy for allogeneic bone marrow transplant patients: a qualitative pilot study. Psychooncology. 2015;24:52. doi:10.1002/pon.3874 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez AM. Assessing the benefit of dignity therapy for adolescents with advanced cancer: a prospective explorative mixed-method study. Palliat Med. 2012;26:551–2. doi:10.1177/0269216312446391 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flad B, Raggl-Schäuble T, Juen J, Wöll E, Sandra M, Kurz M. et al. Dignity therapy at an Austrian acute care hospital: feasibility and acceptance on wards that are not specialised in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2018;32:286. doi:10.1177/0269216318769196 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li H, Richardson A, Speck P, Armes J. Conceptualizations of dignity at the end of life: exploring theoretical and cultural congruence with dignity therapy. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:2920–31. doi:10.1111/jan.12455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vuksanovic D, Green H, Morrissey S, Smith S. Dignity therapy and life review for palliative care patients: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:530–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]