Abstract

Women with heart disease, stroke, and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) experience gender inequities across the health care continuum. The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada conducted needs assessment to inform its approach in addressing health inequities experienced by women with heart disease, stroke, and VCI across the continuum of care. Although specific input is confidential, this article outlines the engagement methods used and the evaluation results. The 3-stage engagement process consisted of an internal content review, 18 in-person discussion groups via a cross-Canada tour, 14 expert interviews, and a collaboration session. In total, 204 and 57 participants were recruited for the cross-Canada tour and collaboration session, respectively. Using the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool, participants scored the engagement processes positively and found participation to be a valuable use of their time. This undertaking highlighted aspects to consider when engaging people with lived experience and how engagement can support the recovery journey. Insights presented throughout this article can help inform future research that seeks to engage stakeholders at a national level.

Keywords: patient engagement, patient experience, heart disease, stroke, vascular cognitive impairment, continuum of care, health advocacy, gender equity

Introduction

Heart and Stroke Foundation in Canada (H&S) is a national health charity with the vision: Life, uninterrupted by heart disease and stroke. Heart and Stroke Foundation in Canada’s 2018 reports titled “Ms. Understood” (1) and “Lives Disrupted” (2) highlighted sex and gender inequities in the provision of care for those with heart disease, stroke, and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI)—primarily due to biased evidence (2/3 of research uses only male participants). Heart and Stroke Foundation in Canada conducted needs assessments to gather feedback from women with lived experience in order to inform its approach in addressing health inequities experienced by women. Although the specific input is confidential, the methods used for engagement and the evaluation results are shared. Heart and Stroke Foundation in Canada’s needs assessment had 3 objectives: demonstrate a model for meaningful engagement, understand the needs of people with lived experience (PWLE)—patients and unpaid caregivers, and make connections and strengthen existing relationships with PWLE.

Methods

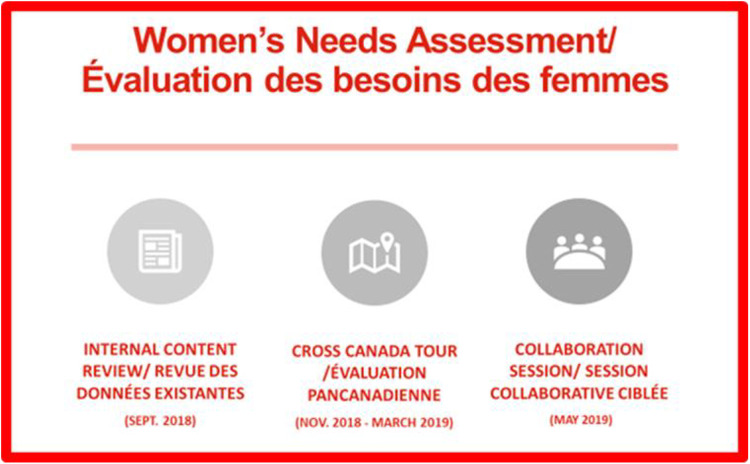

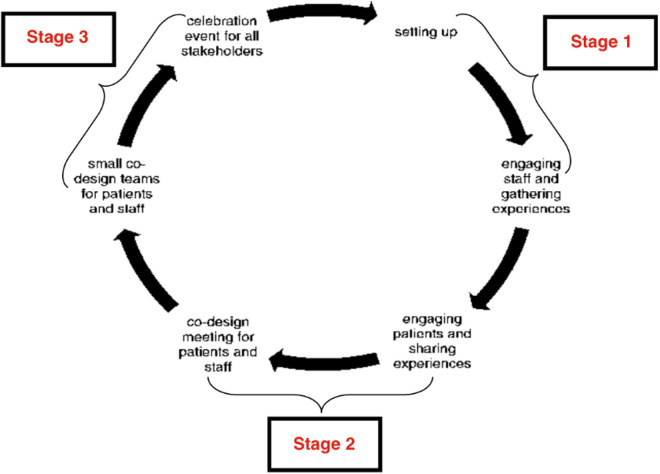

The 3-staged quality improvement initiative (ie, needs assessment) was conducted to identify systemic health care gaps and needs experienced by PWLE. The process included an internal content review, a cross-Canada tour to speak directly with PWLE and one large collaboration session with PWLE codeveloping aspects of a 5-year plan to address systemic disparities (Figure 1). The findings from each stage informed each subsequent stage, and the experience-based codesign cycle (3,4) were adopted as guiding framework (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The three phases of the Women’s Needs Assessment.

Figure 2.

Stage 1: Internal Content Review

Stage 1 consisted of an internal content review (5,6) along with reviewing H&S’s online peer support group discussions. The objective was to review available feedback from women and highlight key areas requiring further exploration in subsequent stages. The internal content review included scanning H&S documents, presentations, reports, or quotes containing feedback from PWLE. To be included, the content must have (1) contained current (2008 or later) H&S quotes, reports, feedback, or data from PWLE in Canada; (2) noted gaps in services and care specific to PWLE mentioning women or applied to both sexes. Content was excluded if it was (1) older than 10 years at the time of review; (2) The data came from clinicians or health care practitioners, or people who have not experienced heart disease, stroke, VCI, or caregiving; and lastly, (3) The outcomes or insights of the content reported were from outside of Canada. An expert reviewer then conducted a qualitative and quantitative meta-analysis of the included documents.

Additionally, the internal content review involved an online peer support group trend analysis conducted in 2 H&S peer support communities. Search terms were developed by 3 internal investigators and verified by an external expert. Translated French terms were included. The qualitative results of the search informed the focus of stage 2: Cross-Canada tour and expert interviews and stage 3: Collaboration session. More specifically, we learned that among women the stages of recovery are experienced differently, and the trauma/mental health impacts of a health event are significant. This led to a full continuum of care exploration and emphasized the need for expert facilitation by someone with mental health training (stages 2 and 3).

Stage 2: Cross-Canada Tour—Recruitment

Participants for the cross-Canada tour were recruited though digital bilingual poster placement on H&S outreach channels. Recruitment messaging noted that H&S wanted to hear from women with lived experience with heart disease, stroke, or VCI OR the informal caregivers of women who met the same criteria. Interested participants meeting the criteria received an invitation to the discussion group closest to them. Provincial H&S staff assisted with selecting interviewees for an additional expert interview component to stage 2. This helped round out representation from certain components of the population: Indigenous women living in Northern communities, those living with aphasia, and those of south and east Asian descent. Interviewees were selected based on their ability to identify the specific needs of women within these populations (eg, health advocacy leads, community health leads).

Stage 2: Cross-Canada Tour—Methods

The cross-Canada tour was necessary to broaden H&S’s understanding of the needs of PWLE across geographical locations and to allow for greater understanding of women’s journeys throughout health care systems. After the cross-Canada recruitment periods elapsed, interested PWLE received an invitation to their local discussion session, including goals of the session, a summary of how their feedback would be used, the importance of collective confidentiality, and an agenda for the session. Potential attendees were informed that they would be compensated for travel and caregiving costs, were offered translation support if required, and were provided the option to attend the sessions remotely if needed. All interested members were able to be involved in either the discussion sessions or a follow-up call.

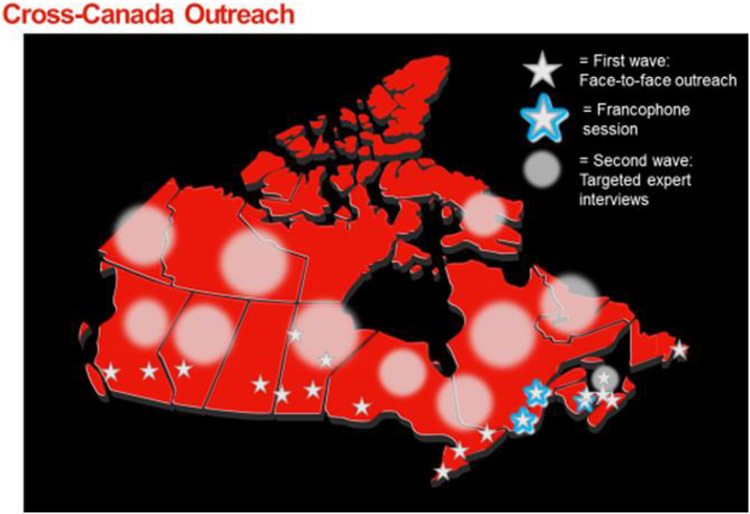

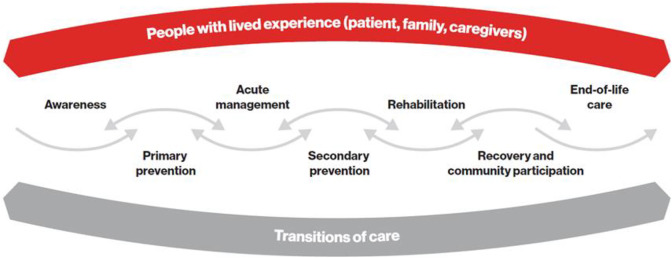

Heart and Stroke Foundation in Canada held 18 in-person discussion sessions throughout the nation (3/18 French; Figure 3). Participants had the autonomy to contribute in whatever way they deemed fit. In order to foster a gender-supportive environment, the same trained female social worker facilitated each session. Sessions lasted 3 hours, with the first half consisting of roundtable introductions and open-ended descriptions of participant health care journeys. The second half consisted of detailed conversation regarding supports and challenges faced by participants across the continuum of care and a brief slideshow. The slideshow highlighted the goals of the broader women’s initiative: (1) Encourage research for and about women, (2) Mobilize Canadians to take action, (3) Improve women’s diagnosis and treatment, (4) Increase awareness, and (5) Facilitate supportive connections. Participants were encouraged to consider their own experiences through the lens of the 5 goals, provide feedback on how H&S could best meet these goals by engaging with PWLE and identify potential gaps within the goals. Feedback was visually placed on a continuum of care map to showcase the value of each contribution and where it fit on the continuum (Figure 4) (7). No personal identifiers were recorded.

Figure 3.

Cross-Canada Outreach Session.

Figure 4.

Heart and stroke continuum of care (7).

Standardized expert interviews were used to fill in demographic gaps observed within the original participants recruited. The interviews followed an identical format to the discussion groups but were conducted over the phone, one on one. For both in-person participants and interview respondents, a visual/color-coded representation of collective feedback was shared after each of the discussion sessions. Participants had joint ownership over their contributions and could make note of any important insights realized after the session or corrections.

All participants were asked to complete the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET) (8), either in person after the discussion session or through an online survey. This tool was used to assess experiential feedback regarding the engagement process itself was anonymous and voluntary. French and English survey findings were amalgamated. Qualitative findings were individually coded and underwent thematic analysis by 2 expert reviewers (one being the stage 2 facilitator). Interrater reliability was assessed. In areas of contradiction, raters discussed and agreed on the likely intent/meaning of the qualitative data. Two additional reviewers assessed the coding with no requested alterations. Results from the cross-Canada tour informed engagement processes and the selection of key topics for the collaboration session.

Stage 3: Collaboration Session—Recruitment

A recruitment email was sent to participants of the cross-Canada tour informing them of the collaboration session. Similar to stage 2, individuals who responded to the poster were then sent an invitation with a detailed agenda and informed that they would be compensated for travel and caregiving costs, offered simultaneous translation support if required, and provided with the option to attend remotely if needed.

Stage 3: Collaboration Session—Methods

The 5 topics chosen for the collaboration session were selected based on frequent points of feedback provided during the cross-Canada tour. Along with the response to invitation, attendees completed a ranking survey to preselect topics they wanted to collaborate on and were assigned their top 2 topics. Participants were then provided with collated feedback from the content review and cross-Canada tour specific to their selected topics and were asked to review these summaries and associated reflection questions prior to the event.

During the collaboration session itself, the room had 5 large circular tables with signage denoting the topic of discussion for each table. Attendees gathered around their assigned tables, which aligned with their top preselected topics of interest. Participants rotated tables midway through the morning switching to their second preselected topic. Each table was facilitated by the H&S staff member most responsible for the associated goal in the Women’s Initiative. Facilitators were matched this way to provide participants with deeper contextual information if needed and to provide the H&S staff member with direct access to PWLE feedback. Voluntary facilitation coaching was offered to table leads ahead of time. A variety of feedback collection strategies such as role-playing, visual mapping, elevator speeches, and storytelling were used to encourage discussion. The focus of the collaboration session shifted during the second half of the day to collect feedback from attendees on H&S’s online presence and digital needs of PWLE.

Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (8) evaluation responses were collected after the event and members were encouraged to sign-up for follow-up engagement opportunities related to the Women’s Initiative. Evaluation data analysis followed the same process as noted in stage 2. A summary of results from the entire 3-stage process were shared with participants in a detailed 48-page report which included acknowledgment of all PWLE contributors. All contributors were offered the opportunity to provide secondary feedback. This report was also shared with H&S staff to inform their Women’s Initiative planning and to foster a greater organizational understanding of the needs of women with lived experience.

Results

Stage 1: Internal Content Review Results

The internal request for literature resulted in 39 documents (5 exclusions based on publication date) published from 2010 to 2018 and represented feedback of over 6600 people. Only 13 (38%) of the 34 included documents identified the gender of the people providing feedback.

More than 1000 conversations were searched during the online peer group trend analysis on November 8, 2018, resulting in 140 hits to terms used in the Women’s Initiative.

Stage 2: Cross-Canada Tour Participation

A total of 204 PWLE (26 Francophones) were recruited for the cross-Canada tour. Discussion groups ranged from 3 to 24 participants, with a mode of 11. In all, 132 (65%) of participants completed the evaluations.

Stage 3

The collaboration session included 57 PWLE with cross-Canada representation and equal balance between those with lived experience of stroke and those with lived experience of heart disease. In all, 34 (60%) completed the evaluations.

Quantitative Evaluation

Quantitative data indicated success in achieving the first objective of the needs assessment: To demonstrate a model of meaningful engagement. For example, all 16 PPEET (8) questions were rated positively at 87% or higher for the cross-Canada tour and collaboration session. More specifically, following the cross-Canada tour, 98% of respondents were confident that the input provided through the engagement process would be used by H&S, and this increased to 100% following the collaboration session. Although 90% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they had a clear understanding of the purpose of the discussion group, this slightly decreased to 87% when asked if they thought the discussion group achieved its objectives. Results from the collaboration session reflected a similar trend with 94% indicating they understood the purpose of the collaboration session, and 91% agreeing or strongly agreeing that the objectives were achieved. The PPEET (8) results highlighted that participants in both stages felt their voices were heard and were satisfied with the engagement initiative.

Qualitative Evaluation

The PPEET (8) administered during the cross-Canada tour and collaboration session included 6 qualitative questions. Results were thematically coded into positive themes and constructive themes by 2 separate reviewers with 98% interrater reliability.

Cross-Canada Tour—Top 2 Positive Themes

Supportive facilitation and discussion—among the open-ended feedback, more than 32% of respondents indicated they felt supported, comfortable, and safe when speaking during the discussion groups. Participants felt a sense of inclusion, and one participant noted they “felt safe with peers who understand.” When asked about the strengths of the discussion group, many responded that the facilitator was crucial in fostering a supportive atmosphere.

Contribution to impact/outcomes, hope, and motivation—Participants felt the discussion groups would influence future work to mitigate gender inequities. When asked about the influence of their feedback, one individual responded, “I feel confident that now with this information there could be positive changes to the healthcare system.”

Cross-Canada Tour—Top 2 Constructive Themes

Need for follow-up—“I would like more feedback when the initiative is complete” was the most common constructive feedback received. Participants voiced that they would like H&S to share future work informed by their insights.

Logistics—The second most common constructive theme received related to logistical issues. Participants indicated they had trouble hearing due to the room being too loud or because of technology issues. Other logistical concerns related to the length of the session (either too long or too short) and time of day.

Collaboration Session—Top 2 Positive Themes

Supportive facilitation and discussion—Supportive facilitation emerged as the most prominent positive theme from the participants. Similar to the discussion groups, the facilitators were vital in ensuring participants felt heard and to keep the conversation flowing.

Meeting others, solidarity, and collaboration—Several attendees noted the value of meeting other PWLE. When asked about the strengths of the collaboration session, one participant said, “meeting women in different circumstances across Canada.”

Collaboration Session—Top 2 Constructive Themes

Not enough time to feel heard—28% of evaluation responses indicated that the session was not long enough, thus impacting the ability to contribute. “More time for engagement was needed” was a common response when asked how the discussion groups could be improved.

Logistics—It was evident through the results that the facility was not ideal. Participants specified that a larger room and a venue with a more accessible layout would improve the session.

Although constructive input was received, qualitative results under the themes “Supportive facilitation and discussion” and “Contribution to impact/outcomes, hope & motivation” indicated that participants felt understood and trusted that their input would make a positive impact on future H&S efforts toward system change. These results denoted achievement of the needs assessment’s second objective: to understand the needs of PWLE. The theme “Meeting Others, Solidarity and Collaboration” highlighted that participants obtained a sense of solidarity with each other and with H&S. This offered an indication that the third objective was accomplished: to make connections and strengthen relationships with PWLE.

Efforts were made to promote diversity however, cultural and ethnic gaps were observed and noted by participants during both the discussion sessions and the collaboration session. In addition, although the overall list of participants was balanced by diagnosis, qualitative findings from the collaboration session highlighted that some participants felt representation of diagnoses were unequally dispersed between table groups.

Survey response rates could have been improved by providing more time for completion. That said, all staff members completed the PPEET (8) following the cross-Canada tour and collaboration session. Taking part in the collaboration session increased staff members’ facilitation confidence and desire for future engagement activities. Staff members found this to be a good use of resources that would add value and guide future work by H&S—indicating positive impressions of a demonstrated model for meaningful engagement.

Discussion

The survey results suggest that the engagement process achieved benefits beyond the intended objectives of the Needs Assessment. Participants valued the opportunity to inform future work that will contribute to closing the gender equity gap in health care and the ability to share experiences among new companions was an unintended therapeutic benefit for many.

The removal of financial and logistical barriers as well as empathetic facilitation were fundamental components to robust engagement. The facilitation experience varied during the collaboration session as tables were led by both staff and PWLE volunteers. Some attendees noted that others used disproportionately longer amounts of time when speaking and attributed this to a lack of facilitation skills. It would have been beneficial to require training for all facilitators.

Qualitative findings from the cross-Canada tour and collaboration session emphasized the importance of considering the venue accessibility and logistical aspects when engaging PWLE. Although this was considered in planning, advance site visits would have been beneficial. In addition, events were held during the day, and limited some individuals’ attendance due to work or travel conflict. Weather conditions also made it challenging for both H&S staff and participants to attend on occasion.

Several PWLE expressed that their advocacy in the sessions was a healing or cathartic exercise and felt a duty to advocate for the next wave of PWLE coming through the health care system. Moreover, advocacy was thought to be part of their recovery journey, specifically an end point that should have been included on the continuum of care map.

Although the 3-stage engagement process proved successful and beneficial to H&S, it did require organizational commitment and support, both financial and human resource, to be properly executed. Prior to utilization of this novel approach, organizational investment toward evidenced-based engagement methodology and commitment to PWLE feedback incorporation is crucial. Evaluation findings noted this sense of organizational trust and commitment to honoring the opinions of those involved.

Conclusion

This unique engagement process was undertaken to help inform H&S’s approach in addressing health inequities PWLE face across the health care continuum by allowing us to see through the lens of lived experience and hear the voices of those nearest to the cause. In the process, new connections were cultivated, and existing relationships were strengthened with PWLE across Canada. Insight gathered informed the development of offerings geared toward women and led to additional engagement opportunities. Organizational and participant benefits beyond the preplanned objectives were observed. In particular, the collaboration and engagement process itself was deemed to be a valuable experience and was seen by PWLE to be a part of their healing journey. The findings will assist to ensure future decision-making includes considerations that would resonate with H&S’s constituents and enhance meaning and value to our work. These findings can be used to inform future engagement endeavors with PWLE in a national context. This article presents a unique model to meaningfully engage PWLE using evidence-based codesign, evaluation, and a relationship stewardship processes.

Author Biographies

Moira E Teed is a social worker and was the senior specialist and liaison for people with lived experience at the Heart and Stroke Foundation at the time of this research. She led phase 2 and 3 of the Women's Needs Assessment and co-led the development of this manuscript.

Julia Ianiro was a master’s student in public health at Western University at the time of this research. She participated in the development of this manuscript during a practicum placement with the Heart and Stroke Foundation.

Cynthia Culhane is a person with lived experience and was an active participant in phase 2 and phase 3 of the Women’s Needs Assessment. She acted as master of ceremony in phase 3 and participated in the development of this manuscript.

Jennifer Monaghan is a person with lived experience and was an active participant in phase 2 and 3 of the Women’s Needs Assessment. She acted as a facilitator in phase 3 and participated in the development of this manuscript.

Judit Takacs is a project lead for Lived Experience, Engagement and Support with the Heart and Stroke Foundation. She led phase 1 and acted as a facilitator in phase 3 of the Women’s Needs Assessment and participated in the review of this manuscript.

Gavin Arthur was the lead for patient engagement at the Heart and Stroke Foundation at the time of this research. He participated in the review of this manuscript.

Amanda Nash is the Health Promotion and Nutrition Manager with the Heart and Stroke Foundation. She assisted in phase 2 of the Women’s Needs Assessment and was co-lead on the development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Ethical approval is not applicable for this article. This article looks at the process and evaluation used for a needs assessment and does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants of the needs assessment for their anonymized information to be published. This article focuses on the assessment process and there are no human subjects in this article. Informed consent is not applicable.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The women’s needs assessment process and evaluation as well as the authorship and publication of this paper was funded in its entirety by Heart and Stroke Canada.

ORCID iD: Amanda Nash  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1791-1359

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1791-1359

References

- 1. Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. 2018 Heart & Stroke Report: Ms. Understood. Heart & Stroke; 2018. Accessed February 1, 2018. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/2018-heart-month/hs_2018-heart-report_en.ashx,2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. 2018 Heart & Stroke Report: Lives disrupted: The Impact of Stroke on Women. Heart & Stroke; 2018. Accessed June 5, 2018. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/stroke-report/strokereport2018.ashx?rev=8491d9c349f7404491f36be67f649c0b&hash=1BCC40A8A71C6EE5CBB3BEE2AD1941B7,2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boaz A, Robert G, Locock L, Sturmey G, Gager M, Vougioukalou S, et al. What patients do and their impact on implementation. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30:258–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donetto S, Tsianakas V, Robert G. Using Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) to Improve the Quality of Healthcare: Mapping Where we are Now and Establishing Future Directions . King’s College London; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual: 2015 edition: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015. Accessed November 15, 2018. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v2.pdf

- 6. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. 2019 Heart & stroke report: (Dis)connected. 2019. Accessed February 7, 2019. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/2019-report/heartandstrokereport2019.ashx?rev=970f91b3504b4194ae93a2ef92272172,2019

- 8. Abelson J. Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET). McMaster University: Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution—Non-Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License. McMaster University; 2018. [Google Scholar]