Abstract

We describe a process of organizational strategic future forecasting, with a horizon of 2035, as implemented by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) on behalf of its members, and as a model approach for other organizations. The participants were members of the 2018–2020 AAN Boards of Directors and Executive Team, moderated by a consultant with expertise in future forecasting. Four predetermined model scenarios of import to our field (1 “expectable,” 1 “challenging,” and 2 “visionary”) were discussed in small groups, with alternative scenarios developed in specific domains. Common themes emerged among all scenarios: the importance of thoughtful integration of biomedical and information technology tools into neurologic practice; continued demonstration of the value of neurologic care to society; and emphasis on population management and prevention of neurologic disease. Allowing for the inherent uncertainties of predicting the future, the AAN's integration of structured forecasting into its strategic planning process has allowed the organization to prepare more effectively for change, such as the disruptions stemming from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The approaches outlined here will be integrated into future AAN operations and may be implemented to a similar effect by other organizations.

Introduction

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has historically utilized a collaborative strategic planning process that engages both physician leaders and the AAN staff, on a continuous cycle, to re-assess the Academy's mission, vision, values, goals, and objectives. Given recent trends in technology, health care delivery, and payment systems, the 2018–2020 AAN and AAN Institute Boards of Directors (Board) participated in a strategic planning session in early 2020 to incorporate a “futurist's framework” that would be relevant for the broad range of its membership.

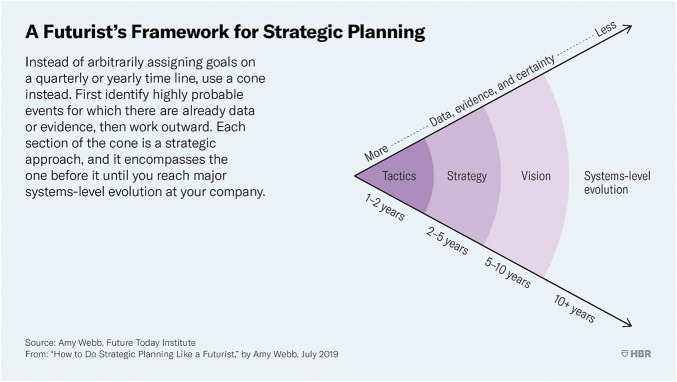

The objectives of the session were to create scenarios focused in certain areas, extending to 2035, and to discuss the elements and key drivers around those scenarios. The Board developed these scenarios with the understanding that as it projected further into the future, there was increasing uncertainty about outcomes—in essence, a time “cone” (figure 1).1 In doing so, consideration of our aspirational futures would lead to enhanced focus on our visionary success, in the hope of improving our ability to perceive and respond to threats or opportunities. Whereas the Board anticipated that the practice of neurology would surely change over the next decade, the Board could not have envisioned the profound consequences that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic would impose just 1 month after it completed this exercise.

Figure 1. Time Cone: A Futurist's Framework.

This illustrates a limitation of future forecasting: the further into the future, the greater the uncertainty. Reprinted with permission from “How to Do Strategic Planning Like a Futurist” by Amy Webb. Future Today Institute, July 20, 2019; hbr.org. Copyright 2019 by Harvard Business Publishing; all rights reserved.

The purpose of this article is to present the process and methods by which established techniques of futuristic strategic planning were used by the Board, to provide a summary of the findings generated as they pertain to neurology, and to show potential adjustments that would allow the AAN to remain indispensable to its members. We present an initial application of this process related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Approach to Futures Planning

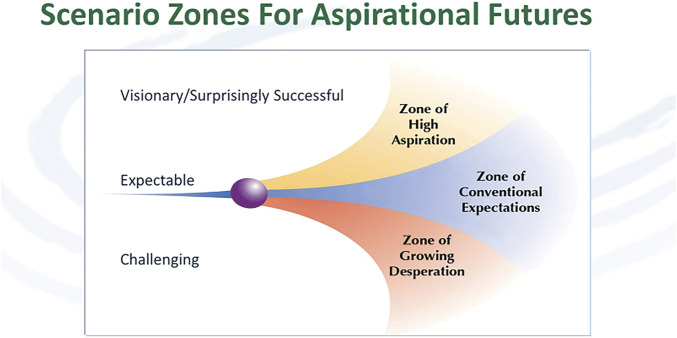

The AAN secured Clement Bezold, PhD, as a speaker and facilitator for the annual strategic planning session in January 2020. He is the founder and chairman of the Institute of Alternative Futures (IAF), a leader in the creation of preferred futures. For example, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, IAF published a document exploring different scenarios—expectable, challenging, and visionary—that set predictions for health care in 2032 (figure 2).2 Our goal was to imagine the future with the detail required to lead to action and improved strategies, based on scenarios developed by the IAF.

Figure 2. Scenario Zones for Aspirational Futures.

The conceptual framework for the various scenarios. Source: Institute for Alternative Futures; used with permission.

In preparation for the strategic planning process, a survey was developed and distributed to all members of the Board prior to the January future planning session, asking about greatest hopes and fears for the neurology profession (tables 1 and 2). Such views might vary according to demographics, sex or gender, type of practice, etc., of each Board member; in this, we recognize that the Board may not be an adequate surrogate sample of the Academy's membership. The AAN strives to have a diverse Board, representative of its membership, but any relatively small group cannot fully capture the diversity of a large organization.

Table 1.

Hopes for the Neurology Profession/Patient

Table 2.

Fears of the Neurology Profession/Patient

The Board also reviewed a series of articles on futures planning, related in process, that might inform its thinking about neurology.1-12

At the planning sessions, the AAN Executive Team and Board members were divided into 4 groups, so as to achieve a breadth of expertise and viewpoint in each group. Our 2035 forecasts were to enhance, interpolate, and expand on adaptations of previously published IAF alternative 2032 scenarios focused on the economy, society, and health care. The small groups reflected on expectable, challenging, or visionary scenarios, and were tasked with considering the implications of their scenario to neurology including incidence/conditions, diagnostic and treatment advances, practice, payment, and other implications.

Initial Scenarios

Scenario 1: Expectable (“Most Likely”)

The economy is transforming, with slow growth, but with rapid automation and associated job loss.

Technology changes our lives in the next decade more than it did in the last 2.

Climate change–related events grow in all regions.

Health care, pushed by economics, technology, and policy, lowers costs and takes care to the patient, including virtual care.

Amazon and other tech companies become major health care players. Provider systems consolidate.

Knowledge explodes, fueled by the “-omics,” personal biomonitoring, big data, and integrated records.

Prediction, prevention, and personalization of treatment become increasingly common for many conditions.

Scenario 2: Challenging (Explores “What Could Go Wrong”)

Although the Board was aware of the incipient pandemic, this was not explored as a specific case, although it was discussed among the authors during the crafting of this article (see Discussion).

Another major recession, high job loss to automation, and severe climate change–related events lead to increased poverty.

Federal government is constrained by debt.

Technology continues to advance, but this increases inequity.

Health care consolidation and bankruptcies grow along with value-based payments.

Distributed models of care, driven by artificial intelligence (AI) and delivered virtually, reduce cost.

Some breakthrough cures and prevention are developed, but these are costly and not covered by most insurers.

Scenario 3: Visionary A (“Zone of High Aspiration”)

Society, government, and the economy transform, driven by values supporting equity and inclusion.

High job loss leads to a guaranteed basic income and other increased support programs, including Medicaid expansion and Medicaid Buy In option.

Health care is shaped by disruptive innovations, including precision/predictive medicine, consumer diagnostic tools, and virtual health assistants; in turn, there is development of regenerative medicine, with slowing of aging, and the ability to address social determinants of health.

Large tech companies enter health care, accelerating disruption. Many consumers buy services directly via online marketplaces.

Scenario 4: Visionary B (“Zone of High Aspiration;” Some Differences in Outcomes and Pathways)

At a national level, hearts, minds, and policies shift, moved by empathy, equity, inclusion, and sustainability, to build cultures of health.

Tech, AI, and virtual reality reshape work and play, including health care.

Energy, food, and local manufacturing technologies are applied to lower the cost of living for low-income families.

Health care addresses the triple aim of care, education, and science, while tech supports personalization and virtual on-demand delivery of most care.

The health care industry consolidates and most care is value based.

Millions receive care through high deductible health plans purchased out of pocket on Amazon-like marketplaces that compare provider outcomes and costs.

Consumers want to become “previvors,” anticipating and preventing conditions.

Implications and Outcomes

Once developed, the small groups were then instructed, based on the outlined points, to consider “if x, then what?” for neurology, and then to interpolate and make further assumptions as needed: for example, if there were forecasts for advances across medicine, to consider whether and how they would be applied to neurologic conditions or practice, and make assumptions on how they will develop and identify implications. Each small group reported out their findings for further discussion by the full Board.

During discussion, specific questions were as follows: What elements should be included in AAN 2035 scenarios? What are the key drivers shaping developments in the expectable, challenging, and visionary scenarios? Major elements or themes, and key drivers, were identified (tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Major Elements Surrounding 2035 Scenarios

Table 4.

Key Drivers Identified in Board Discussion for Neurology

The 4 small groups of Board members were then asked in a second exercise to discuss those elements that might be included in alternative AAN 2035 scenarios and key drivers. In doing so, the groups focused on developing alternative forecasts related to 3 topics: (1) health care systems and payers; (2) AI, personal biomonitoring, and big data applications in health care and neurology; and (3) neurology care and practice—teams and solo practice, diagnostic and treatment tools, degree of neurology care provided by non-neurology trained providers, and neurology workforce.

As forecasts for each of the 3 topics were developed, the goal was to refine, adjust, or extend the topic forecast. As virtually all the topics are shaped by multiple forces, the groups were asked to describe what is enabling or shaping their forecast, e.g., what science or technology advances, regulation, or financing/policy changes may occur? For each forecast, the groups were asked to consider what is needed to further develop or confirm the forecast, i.e., What developments or milestones are needed to enable the forecast to come into being? What research and forecasts should be gathered, or which experts should be interviewed? The ultimate goal was a series of actionable forecasts that AAN leadership could use to refine the society's vision, mission, and goals, on behalf of its membership.

The final AAN 2035 scenarios were completed as follows:

Scenario 1: The “Expectable” Future

As a specialty in this version of the future, neurology will continue to evolve along with the rapidly changing aspects of patient interaction, practice environment, and health care demands.

External forces, including economic pressures and technological advances (encompassing increasing complexity of diagnoses), will shape the utilization of neurologic expertise, with a potential shift in the care pyramid towards neurologists seeing only the most complex cases.

Biomedical advances may have a substantial effect on the prevalence of neurologic disorders amendable to novel cures (e.g., single-gene disorders), while complex disorders (such as stroke and dementia) prevalence will grow with aging of the population, with increasing disparities in access to health care. Social justice will compel changes in addressing disparities.

New diseases may emerge with global influences on health care, but will require neurologic expertise in diagnosis and management of their neurologic manifestations.

To remain productive, neurologists will need to gain proficiency in technological innovations, including the virtual models of care delivery, interfaces with AI, biomonitoring, and big data applications; and with subspecialty practice and research.

Data privacy and bioethical considerations will remain central to all growing technological advances and care delivery models, adding to the demands on the field.

The humanistic aspects of neurologic disorders and the growing ability to deliver patient-centric, team-based care by neurologists may prove indispensable in the era of mounting demands of the ever-changing health care landscape.

Scenario 2: Challenging

In this scenario, there is increasing wealth disparity, with a growing percentage of wealth concentrated in the top 1%.

Increasing poverty levels will challenge the federal government's ability to offer safety net aid, with subsequent escalation in health care disparities.

Health care disparities would likely result in a higher dependency on local and state government and would lead to population migration looking to find safer places to live.

The economic decline will accentuate the dilemma patients have in budgeting between health care and other needs such as housing.

Technological and scientific advances are still expected in this scenario but access to those will be for the fortunate few who still have private insurances or independent wealth. The less fortunate patients will not be able to afford access and will not benefit.

In this setting of insecure health care, there are poorly conceptualized AI tools that take short cuts and provide algorithmic but unsophisticated health care to those who cannot afford to see a neurologist.

As health care becomes cost prohibitive, or medical science is doubted, more patients may seek health care from other areas such as naturopaths, chiropractors, and unqualified laypersons.

The neurologic field will have a harder time recruiting into its ranks as the new graduates, burdened with growing debt, will not choose a field with uncertain income. Neurologists may be more reliant on the “gig” economy and set up more concierge type practices that further contribute to health disparities by offering care to those that can afford it. Medical tourism grows and there may be a “brain drain” of US-trained neurologists to other countries where they can be offered a more secure income and lifestyle.

There may be limitations in travel, whether due to climate change, increases in communicable diseases, or inability to afford travel. This may markedly influence the AAN's education platforms and annual meetings. It may not be feasible to consider meetings where approximately 14,000 members get together yearly to learn, advance knowledge, and grow from community support. The COVID-19 pandemic provides one example of such a scenario. The necessity of offering a variety of education venues and embracing technology and virtual learning must be discussed and implemented as necessary.

Scenario 3: Technology Revolutionizes Health Care

As specialists in this version of the future, neurologists will need to learn how to integrate their practices with the technology solutions that industry has developed and patients expect. This will require competencies in performing or using complex analytic and informatics tools.

Neurologists will have to be able to articulate their value to payers, who will be heavily consolidated with extraordinary pricing power, and also to patients who will direct their discretionary spending to specialty services that deliver the biggest bang for the buck. Value will need to be expressed to patients and other third parties in quantitative as well as qualitative terms.

With data-driven algorithms for diagnosis of many common neurologic diagnoses, neurologists may be able to focus on a patient population enriched with complex disorders. While clinical volumes may be lower proportionately, neurologists may find themselves caring for a patient population better suited to their capabilities, with potential associated improvements in neurologist professional well-being.

Advances in neurologic therapeutics will allow neurologists to offer disease-modifying treatments to growing numbers of patients. Prevention of disease will become a more widely accepted focus in neurologic care.

To maintain a talented pipeline, neurologists will need to foster an inclusive culture that matches our society and demonstrate the excitement of revolutions in treatment of neurologic disease. Training programs will require considerable updates to incorporate content that prepares trainees for a more complex clinical environment.

This aspirational vision of a technology-enhanced practice of neurology comes with some challenges. Change management will be a crucial competency for neurologists who must adapt their skills and teams to a rapidly changing practice milieu.

Scenario 4: Health Policy Transforms Care Delivery

This scenario should reflect an ambitious agenda, whereby society is healthier, but also has access to higher quality, point of care service at reduced costs. Neurologists play a critical role in this transformation, supporting patients' and communities' health, and leading neurologic disease care at the bedside, regional, and national levels. These goals would be best accomplished by (1) defragmentation of the health care system, (2) massive expansion of health promotion efforts, (3) technological innovation, (4) expanded role of neurologists in leadership, and (5) patient empowerment through improved dissemination of scientific information.

Society recognizes the real costs, economic and clinical, incurred by a fragmented health care system. As a capitalist culture, political parties find common ground and meaningful compromises to better balance the values of social support and profit, maintaining innovation in a humane way. Defragmentation of care delivery begins as Medicaid expands across state lines, ensuring all Americans can receive preventive care, health promotion services, and catastrophic services. These benefits are consistent across all states. Further, patients may buy-in at a cost-effective rate, allowing all Americans access. Because these services are offered to all Americans in a more cost-effective manner, employers decrease their health benefit costs, instead focusing on added health benefits for their employees. Individuals retain options to purchase additional insurance packages to meet their needs as well.

Health promotion grows in importance and technology empowers patients and communities to understand and address their social determinants, such as safe housing, nutrition, quality education, and access to economic and job opportunities. Hospitals expand their roles within communities to accelerate these efforts; this results in being financially rewarded for their successes, allowing additional financial diversification from their core income of disease management and elective procedures.

There is an exponential acceleration in technological advancements in care delivery. Technology companies play pivotal roles in (1) new methods for remote monitoring of diseases; (2) improved communication platforms to create a more immersive and comprehensive telehealth experience, allowing patients to receive high quality of care at distant sites; (3) improved AI to support prevention at the patient or community level, as well as individual patient diagnosis and treatment planning; and (4) health services on demand. Neurologists benefit as well with enhanced support in medical record documentation.

The relationship between neurology leaders and government representatives continues to grow, building greater trust and allowing neurologists more oversight over value-based care models. Through growth in the AAN's Axon registry, neurologists continue to practice in the manner in which they are most comfortable (in-person or virtual visits), as their de-identified patient data are uploaded without additional time, effort, or cost to their practices. Data encryption and protection remains a top priority. Through real-time dashboard reports generated from the registry, neurologists can monitor successes and challenges, and compare their validated outcomes to national and regional variations. Commercial payers and employers realize the cost savings associated with these reports and further collaborate to support centralized information. Because of trust and relationship development, payers also share cost data with providers, allowing further enhancement of the payer–provider alliance and support of the patient and the community as the centers of care.

Communication strategies also evolve to support patients, taking complex information and making it understandable to build empowerment, trust in science, and reductions in the stigma of neurologic illness. As valid information becomes more transparent, disseminated, and automated, neurologists once more place their full focus on informed patients, addressing health promotion and disease management, without worrying about extra clicks, administrative burdens of prior authorizations or step therapies, or patient volume, for their financial well-being.

Scenario 5: Post COVID-19 Pandemic

A Board member who served as leader for one of the visionary small groups incorporated the framework for our initial 2035 scenarios into a “scenario 5” that contemplates the future in the context of the current pandemic. While not part of our initial process, this further illustrates the importance of long-term planning to broaden our mission perspective even when our focus and energies are being spent on more immediate priorities.

Deregulations and payment parity from government and commercial payers allowed the rapid deployment and acceptance of telehealth. Digital technologies not only demonstrated capabilities to support this type of widespread care delivery, but also allowed opportunities to work as a community and disseminate best practices among each other on a national, if not global, level. Preliminary evidence has since supported that telehealth delivers quality care; a satisfactory experience for providers, patients, and caregivers; and increased accessibility, convenience, and efficiency for patients or their caregivers. Telehealth has become etched into the fabric of care delivery and there will be increasing recognition and value to allow ongoing access to care across state lines and where services are needed. Mass production of additional technologies to support telehealth, such as remote stethoscopes, should reduce the price of the goods, and allow expanded telehealth at home or at local, secure health centers where additional remote monitoring devices may be used. Nonetheless, payment levels for telehealth will likely change after the public health emergency resolves. Neurology will need to maintain vigilance as malpractice cases will likely rise as well.

AI has played a prominent role during the COVID-19 pandemic, including predictive modeling, virus understanding, pharmaceutical research and development, management of services and resources across health care centers, and data analysis to shape policy decisions. However, current use tends to be limited to larger corporate entities. Expanding production of AI systems will further reduce prices of these services, allowing individual neurologists to access machine learning and AI algorithms to not only evaluate their patients at the bedside but to detect and forecast trends in their communities.

COVID-19 also brought to light many of the challenges of our current health system, including the lack of a robust public surveillance system, the negative consequences on populations with comorbid medical conditions that may have been lessened with better management of social determinants, and the lack of resource allocation systems resulting in excess or deficits in supplies across geographies. Neurologists can play pivotal roles to leverage technologies, lead their systems, and advocate for policy changes to better resolve these gaps not only for neurology, but at a more global level.

The financial ramifications of the pandemic will have far-reaching implications. Shrinking margins in private practice may lead to provider consolidation into larger networks and systems while salaries and benefits to employed physicians may decline. While medical school costs have revealed considerable elasticity in terms of student applications, it is not known whether the field of neurology will increase, stay the same, or decrease when students realize their incurred debt will need to be repaid. Travel nationally and internationally will become more restricted due to increasing costs and fears, risking reduced networking and scientific collaboration and discovery. Neurologists will rely more heavily on technological interfaces to expand their professional circles.

While barriers to reaching aspirational scenarios will be restricted due to the more limited upfront availability of funds for investment, overwhelming concerns of another pandemic may force government and other stakeholders to increase expenditures to ensure a viable health care delivery system in the near and distant future.

Incorporation and Application of Futures Planning

This exercise in futures planning by the AAN Board and the AAN Executive Team was instituted as part of annual strategic planning. Whereas all strategic planning takes the future into account, this was the first attempt to consider long-range planning to prepare a process by which the AAN could take account of possible alternative futures and prepare for them. As the timeline gets longer, uncertainty grows, so planning necessarily took into account growing uncertainty. At the conclusion of its futures planning discussion, the Board discussed what would be needed to further develop the 2035 scenarios, including involvement of experts or other sources of forecasts, future topics to consider, and optimal uses of the scenarios for AAN member learning and AAN visioning and strategic planning.

The COVID-19 pandemic serves as an example, perhaps extreme, of how some aspects of scenario 2 (challenging) and scenarios 3 and 4 (technology and health care delivery) might have been utilized at a practical level. For example, telehealth has been growing—it is routine for stroke care and has increasing evidence in outpatient neurology, Parkinson disease and stroke perhaps being the best examples.13,14 These areas of telehealth presage the use of telemedicine more generally; anticipating such a future compels consideration of greater advocacy efforts and the growth of the technologies to support telemedicine practice, billing considerations, and security measures.

At the start of this exercise, scenario 2 (“challenging”) seemed less likely than the “expectable” or aspirational scenarios (3 and 4). A few weeks later, the COVID-19 pandemic markedly affected all our lives: patients stopped coming to the office; elective surgeries shut down; hospitals converted regular wards into intensive care units dedicated to treatment of patients most severely affected by COVID-19; shelter in place orders led to distance learning. There were conference cancellations, and for many neurologists, furloughs or pay cuts were instituted, making this scenario less far-fetched, even prescient. With national protests regarding social injustice, resulting from decades (if not centuries) of disparities, this scenario seemed to be more “expected,” on a shorter timeline than anticipated. The AAN will need to plan for a more unstable future where social justice, equal access, and outside pressure affecting the emotional, physical, and financial well-being of our members will play a large role in sculpting how we continue to be indispensable to our members.

This futures planning effort better positioned the AAN for the pandemic. As COVID-19 became our new reality, the importance of futures planning principles learned from these efforts was apparent (see appendix, links.lww.com/WNL/B367). The AAN Executive Team and Senior Leaders, under the leadership of the new CEO Mary Post, immediately embarked on scenario planning, using a STEEP analysis (i.e., identifying social, technology, economic, environment, and political factors) to identify key drivers and trends, and translating that analysis to develop multiple future scenarios that were considered by the Board of Directors in the context of the Academy's already existing 2020 strategic and operational plan.15 A “most likely” Lingering Disruption scenario was embraced by the Board, which framed deliberation by the Executive Team on programmatic priorities for building the 2021 AAN budget and strategic plan.

Our view of the future was not entirely dystopian. Although the challenging scenario might appear overwhelming, each group member recognized the potential for hope after decline. Disparities such as lack of access could be sources of inspiration to aspirational philanthropists and corporations to embrace and develop more social justice forums. Communities might develop a stronger drive towards volunteerism and the medical community may become less financially driven and more focused on health as a right for all.

There were, of course, limitations to our approach. While the AAN strives to have a diverse Board, such a small sample of individuals (10 men and 7 women, including 2 Black members and 1 Asian member, and 2 pediatric neurologists) cannot be a strong surrogate sample of our society's membership. Just as research studies often rely on surrogate measures, with the value of the work dependent on the quality of the surrogates, the success of any futures planning relies on the input of those developing its scenarios. The AAN should seek reactions to these efforts, and seek additional input, so as to inform more broadly its preparedness strategies. We would encourage members to contact the AAN Chief Governance and Strategy Officer (Bruce Levi, JD, at blevi@aan.com) with their perspectives.

Another limitation of our futures planning process was that it represented a first step; as such, this report outlines the processes and methods used to develop our scenarios. Our discussion did not extend greatly into the exact means by which the AAN will utilize the scenarios, which is a job best carried out by staff, who will work to accomplish the Academy's mission through the operational processes they develop. Whereas many scenarios can be anticipated, there are many more that cannot, and we did not define the optimal number or types of scenarios to model. We anticipate an iterative process: as the operational aspects are worked out, this will inform how to improve the development of future scenarios, whether related to specific topics (e.g., social justice) or to how to improve the process by which scenarios are developed. One clear outcome, as evidenced by the COVID-19 experience, is that futures planning is essential to the AAN and similar organizations.

Our process was soundly conceived and carried out, but there is more work to do. We anticipate detailed work on select areas, once identified, will be necessary, the COVID-19 pandemic being a prime example. Because the AAN has as its vision to be indispensable to its members, such efforts will be conceived and executed with this principle in mind.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Clement Bezold, PhD, for facilitating the strategic planning session and Karen Kasmirski for assistance with manuscript formatting.

Glossary

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- AI

artificial intelligence

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- IAF

Institute of Alternative Futures

Appendix 1. Authors

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Webb A. How to do strategic planning like a futurist. Harvard Business Review. July 30, 2019. Accessed October 5, 2020. hbr.org/2019/07/how-to-do-strategic-planning-like-a-futurist. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute for Alternative Futures. Health and health care in 2032: report from RWJF Futures Symposium, June 20–21, 2012. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://wayback.archive-it.org/13466/20200205002414/https://altfutures.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/2012_Report_Health-and-Health-Care-in-2032-Scenarios.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco RL. Neurology: challenges, opportunities, and the way forward. Neurology 2019;93(21):911-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu SH, Peck J, Weinstein SM, Arikan Y, Bell KR, Kaelin DL. Physiatry practice now and in 2032: how to thrive in the post-health care reform world. PM R 2014;6(10):876-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare advantage checkup. N Engl J Med 2018;379(22):2163-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DK, Pagel C, Koller CF. The future of health care reform: a view from the states on where we go from here. N Engl J Med 2018;379(23):2189-2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joynt Maddox KE, McClellan MB. Toward evidence-based policy making to reduce wasteful health care spending. JAMA 2019;322(Number 15):1460-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shortell SM. U.S. health care system reform is not yet at the tipping point. The Commonwealth Fund blog; January 14, 2020. Accessed October 5, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/us-health-care-system-reform-not-yet-tipping-point. [Google Scholar]

- 9.20 medical technology advances: medicine in the future, parts I and II. The Medical Futurist. October 17, 2019. Accessed October 5, 2020. medicalfuturist.com/20-potential-technological-advancesin-the-future-of-medicine-part-i/#. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatcher JM, Adams JL, Anderson ER, et al. Telemedicine in neurology: Telemedicine Work Group of the America Academy of Neurology update. Neurology 2020;94(1):30-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callaghan BC, Burke JF, Kerber KA, et al. The association of neurologists with headache health care utilization and costs. Neurology 2018;90(6):e525-e533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute for Alternative Futures. Primary care 2025: a scenario exploration. 2012. Accessed April 30, 2020. https://kresge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IAF-PrimaryCare2025Scenarios.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Achey M, Aldred JL, Aljehani H, et al. The past, present and future of telemedicine for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2014;29(7):871-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wechsler LR, Demaerschalk BM, Schwamm LH, et al. Telemedicine quality and outcomes in stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2017;48(1):3-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta A. Environmental and pest analysis: an approach to external business environment. Merit Res J Art Soc Sci Humanities 2013;1(2):13-17. [Google Scholar]