Abstract

Objective

Black and Hispanic survivors of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are at higher risk of recurrent intracranial bleeding. MRI-based markers of chronic cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) are consistently associated with recurrent ICH. We therefore sought to investigate whether racial/ethnic differences in MRI-defined CSVD subtype and severity contribute to disparities in ICH recurrence risk.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Massachusetts General Hospital ICH study (n = 593) and the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study (n = 329). Using CSVD markers derived from MRIs obtained within 90 days of index ICH, we classified ICH cases as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)–related, hypertensive arteriopathy (HTNA)–related, and mixed etiology. We quantified CSVD burden using validated global, CAA-specific, and HTNA-specific scores. We compared CSVD subtype and severity among White, Black, and Hispanic ICH survivors and investigated its association with ICH recurrence risk.

Results

We analyzed data for 922 ICH survivors (655 White, 130 Black, 137 Hispanic). Minority ICH survivors had greater global CSVD (p = 0.011) and HTNA burden (p = 0.021) on MRI. Furthermore, minority survivors of HTNA-related and mixed-etiology ICH demonstrated higher HTNA burden, resulting in increased ICH recurrence risk (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

We uncovered significant differences in CSVD subtypes and severity among White and minority survivors of primary ICH, with direct implication for known disparities in ICH recurrence risk. Future studies of racial/ethnic disparities in ICH outcomes will benefit from including detailed MRI-based assessment of CSVD subtypes and severity and investigating social determinants of health.

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the most devastating form of stroke, accounting for >40% of all stroke-related morbidity and mortality.1,2 Survivors of ICH are at high risk of recurrent ICH, which is particularly fatal.3-6 Individuals of Black and Hispanic racial/ethnic background are at an even higher risk for recurrence, and thus mortality, compared to their White counterparts.7 Hypertension is the most potent risk factor for first-ever and recurrent ICH.8,9 While minority ICH survivors in the United States display greater hypertension severity and higher blood pressure variability, these differences in hypertension control do not fully account for disparities in ICH recurrence risk.7 Identifying additional risk factors for recurrent ICH among minority populations is required to guide future clinical research, to develop more effective treatment guidelines, and to inform public health efforts.

Cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD), a disorder of the arterioles, capillaries, and venules of the CNS, underlies the vast majority of primary ICH.10,11 CSVD presents in 2 major subtypes: cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and hypertensive arteriopathy (HTNA). These can be distinguished via neuroimaging, with recent evidence suggesting that a not negligible group of patients with ICH show overlap between the 2 subtypes.12 CSVD severity is typically assessed via MRI-based imaging markers, including white matter hyperintensities (WMH), lacunes, enlarged perivascular spaces (EPVS), cerebral microbleeds (CMBs), and cortical superficial siderosis (cSS).13 These markers are consistently associated with increased risk of recurrent ICH, reflecting the central role of CSVD in ICH etiopathogenesis.14,15

Therefore, we sought to investigate whether (1) CSVD subtype or severity differs by self-reported race/ethnicity among ICH survivors and (2) racial and ethnic differences in CSVD subtype and burden contribute to higher rates of ICH recurrence. For this purpose, we leveraged existing data from 2 large longitudinal studies of ICH: the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) ICH study.

Methods

Participating Studies

We analyzed prospectively collected data of primary ICH survivors enrolled in 2 longitudinal studies. The ERICH study is a multicenter, multiracial, case-control study of ICH.16 ERICH enrolled 3,000 ICH cases and 3,000 ICH-free controls of self-identified White, Black, and Hispanic race/ethnicity (1,000 case-control pairs in each group) across 19 participating centers throughout the United States. Enrollment in ERICH took place between August 2010 and August 2017. For the purpose of the present analyses we included ICH cases enrolled in ERICH who fulfilled all the following criteria: (1) were alive at time of discharge from hospitalization for index ICH, (2) underwent brain MRI within 90 days of index ICH, and (3) were eligible (per Institutional Review Board statute) for enrollment in the longitudinal extension of the ERICH study with longer-term follow-up for recurrent stroke. The MGH ICH study is a single-center, longitudinal cohort study of ICH.5,7 Participants were recruited among consecutive patients presenting with a diagnosis of primary ICH at MGH between January 2006 and December 2017. Because MGH was one of the enrollment centers for the ERICH study, we excluded MGH participants enrolled in ERICH from all analyses of the ERICH dataset to avoid data duplication.

Enrollment Eligibility Criteria

Both studies enrolled patients ≥18 years of age who presented with an acute, primary ICH confirmed by CT scan (obtained within 24 hours of symptom onset) and provided informed consent (patient or surrogate) for longitudinal follow-up after ICH. Individuals with intracranial hemorrhage secondary to trauma, conversion of an ischemic infarct, rupture of a vascular malformation or aneurysm, and brain tumor were excluded.7 For the purposes of the present study, participants on oral anticoagulation at time of ICH were considered to have been diagnosed with spontaneous ICH. We also excluded individuals who did not receive a brain MRI within 90 days of symptom onset. Likewise, ICH survivors with MRIs considered to be uninterpretable by trained study staff were not included.

Baseline Data Collection

Trained study staff collected information of demographics and social and medical history in both studies via in-person interview of patients (and/or reliable informants) at time of enrollment.5,16 We then obtained additional information via review of medical records. Participants or informants also provided self-identified race and ethnicity, choosing from categories recommended by the NIH for use in research studies. For the purpose of this study, we determined self-reported race/ethnicity as White (i.e., non-Hispanic White), Black (i.e., non-Hispanic Black), and Hispanic (i.e., self-identifying as White-Hispanic or Black-Hispanic).7

Neuroimaging

CT and MRI Data Collection

All CT and MRI scans were deidentified, digitalized, and uploaded to the central neuroimaging repository at MGH for both the MGH-ICH and ERICH studies. All neuroimaging analyses for both studies were conducted by study personnel at MGH blinded to clinical and follow-up information. Brain MRIs were obtained with either 1.5T or 3.0T MRI scanners. They included (at a minimum) whole-brain T1-weighted, T2-weighted, T2*-weighted gradient recalled echo (T2*-GRE), diffusion-weighted imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient map, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR).12,16,17 For a subset of patients in both studies, blood-sensitive sequences included susceptibility-weighted images (SWIs). In the uncommon scenario of a patient having both a T2*-GRE and SWI available, we reviewed the SWI.

CT and MRI Data Acquisition and Analyses

We analyzed admission CT scans to determine ICH location, hematoma volume, and presence of intraventricular blood according to previously validated methodology.5,16 All MRI scans were reviewed by 2 trained study investigators (J.P.C., M.P.) blinded to clinical and follow-up information. Study staff extracted information for CSVD MRI-based markers in agreement with the Standards for Reporting Vascular Changes on Neuroimaging.13 The interrater agreement (Cohen κ) for all CSVD markers analyzed ranged from 0.91 to 0.95 and therefore were deemed excellent.18 WMH were defined as a hyperintense signal abnormality on FLAIR without cavitation. WMH severity was evaluated and visually graded on axial FLAIR sequences with the Fazekas scale.19 We defined lacunes as a round or ovoid, subcortical, fluid-filled (similar signal as CSF) cavity between 3 and ≈15 mm in diameter.13 To be defined as lacunes, the lesions had to be hypointense in T1-weighted images and have a central CSF-like signal with a surrounding rim of hyperintensity on FLAIR. GRE/SWI sequences were also reviewed to prevent the incorrect classification of CMBs as lacunes.17 We classified lacunes according to anatomic location as lobar and nonlobar.12,17 For each location, we determined the presence and count of lacunes. CMBs were defined as round or ovoid hypointense lesions of up to 10 mm in diameter on axial blood-sensitive MRI sequences (T2*-weighted GRE or SWI), devoid of signal hyperintensity on T1-weighted or T2-weighted sequences, and distinct from vessel flow voids or potential mimics.13,20 We determined the presence and count of CMBs according to their location as lobar and nonlobar. EPVS were defined as small, round, or linear structures of CSF intensity with a diameter generally <3 mm that follow the course of perforating vessels without a T2-hyperintense rim around the fluid-filled space. EPVS were rated in the basal ganglia (BG) and the centrum semiovale (CSO) on axial T2-weighted images in line with a validated visual rating scale (0 = no EPVS, 1 = <10 EPVS, 2 = 11–20 EPVS, 3 = 21–40 EPVS, and 4 = >40 EPVS).21 We defined cSS as a well-defined curvilinear hypointensity on T2*-GRE or SWI over the outer surface of the cortex and rated it using the cSS multifocality score (range 0–4; 0 = no cSS, 1 = mild and unifocal cSS; 2–4 = severe or multifocal cSS) and further classified it as focal (restricted to ≤3 sulci) and disseminated (diffuse to >3 sulci).22

MRI-Based CSVD Scores

Using a recently described and validated total CSVD score, we rated global CSVD burden on an ordinal scale from 0 to 6 (table 1).23 We allocated 1 point for presence of (1) lacunes; (2) 1 to 4 CMBs; (3) moderate to severe BG EPVS (>20); and (4) moderate WMH (total periventricular + subcortical WMH grade 3–4). We allocated 2 points for presence of (1) ≥5 CMBs and (2) severe WMH (total periventricular + deep WMH grade 5–6). We also evaluated total CAA burden on MRI using a recently validated ordinal score that ranges from 0 to 6 (table 1).24 One point was allocated for presence of (1) 1 to 4 lobar CMBs; (2) presence of moderate to severe CSO EPVS (>20 CSO-EPVS); (3) deep WMs ≥2 or periventricular WMH >3; and (4) focal cSS. We allocated 2 points for (1) ≥ 5 lobar CMBs and (2) disseminated cSS. Finally, we evaluated HTNA burden on MRI using a previously validated ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 4 (table 1).25 One point was allocated for presence of (1) lacunes; (2) periventricular WMH grade 3 or deep WMH grade 2 to 3; (3) presence of ≥1 deep CMBs; and (4) presence of moderate to severe BG EPVS (>10 BG EPVS) (figure 1).

Table 1.

CSVD Scores Based on MRI Data

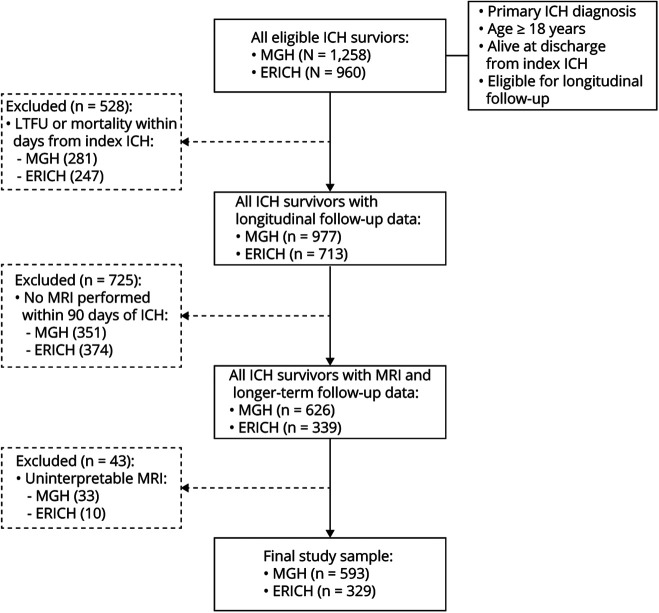

Figure 1. Flowchart of Participant Enrollment From the ERICH and MGH-ICH Studies.

ERICH = Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage; ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage; LTFU = lost to follow-up; MGH = Massachusetts General Hospital.

MRI-Based ICH Etiologic Classification

All patients with ICH were classified on the basis of the location of ICH and CMBs and presence of cSS as HTNA-related ICH, CAA-related ICH, and mixed ICH.12 Patients with HTNA-related ICH had strictly deep (when located in the BG, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum) hemorrhages with or without exclusively deep located CMBs (lobar CMBs and cSS not allowed). Patients with CAA-related ICH had lobar ICH involving the cerebral cortex and the underlying white matter with or without exclusively lobar located CMBs and cSS (deep located CMBs not allowed), meeting modified Boston criteria for probable and possible CAA.26 Patients with mixed ICH fulfilled 1 of the following criteria: (1) lobar ICH and ≥1 deep CMBs, (2) deep ICH and ≥1 lobar CMBs or presence of cSS, or (3) deep and lobar ICHs with or without CMBs in any location.12

Longitudinal Follow-up

ICH survivors and their caregivers were interviewed by dedicated study staff (blinded to baseline and neuroimaging information) at 3, 6, and 12 months after the first ICH and every 6 months thereafter for both studies following established protocols.5,16 Study staff collected medical records and information from participants pertaining to recurrence of ICH and current medication regimens. We supplemented telephone-based collection of follow-up data with semiautomated review of longitudinal electronic medical records as previously described.5 We also queried the Social Security Death Index national database as an alternative way of identifying deaths among ICH survivors.

Statistical Methods

Overall Analysis Plan

We first sought to determine whether minority ICH survivors (i.e., non-White) demonstrated at the time of their index ICH (1) higher CSVD burden on MRI or (2) differences in proportions of CAA or HTNA. We next assessed the impact of disparities in CSVD burden and subtype on ICH recurrence risk.

Variable Definitions

Age at index ICH was analyzed as a continuous variable. Race/ethnicity was analyzed as a dichotomous variable, indicating self-reported White vs minority race/ethnicity. Educational level was dichotomized with the use of a cutoff of ≥12 years of education. CSVD MRI markers were analyzed as described above, with individual variables used for each marker of interest (WMH, lacunes, CMB, cSS, and EPVS). The outcome of interest was recurrent ICH, defined on the basis of concordance between information obtained from patients/surrogates and review of medical records (including review of neuroimaging).

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses

Categorical variables were compared by the Fisher exact test (2-tailed) and continuous variables by the Mann-Whitney rank-sum or unpaired t test as appropriate. We determined factors associated with ICH recurrence in univariable analyses using Kaplan-Meier plots, with significance testing via the log-rank test. Patient data were censored only in the case of death or loss to follow-up. All our models were adjusted for age, sex, and study source. We performed multivariable analyses using competing risk regression models via the Fine and Gray method.27 We initially included in multivariable modeling all factors associated with ICH recurrence in univariable analyses with values of p < 0.20. Because of potential associations between ICH recurrence and use of antiplatelet agents or oral anticoagulants during follow-up, we prespecified adjustment for these variables in our multivariable models (regardless of p value). On the basis of our predefined study goals, we also included self-reported race/ethnicity, CSVD subtype (CAA, HTNA, mixed), and CSVD severity (global burden score) in all multivariable models (regardless of p value). We also included data source (MGH-ICH vs longitudinal extension of ERICH) and time from ICH to MRI acquisition as covariates in all models. We subsequently used backward elimination procedures to arrive at a minimal model including only variables associated with ICH at p < 0.05. Multicollinearity was assessed by computing variance inflation factors for all variables. The proportional hazard assumption was tested via graphical inspection and calculation of Schoenfeld residuals.

Multiple Testing Adjustment

We corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method for adjustment.28 We report p values after FDR adjustment of original results. All significance tests were 2 tailed, and significance was set at p < 0.05 (after FDR adjustment). All analyses were performed with R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), version 3.6.2.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions, and informed consent was obtained from all participants or their authorized surrogates.

Data Availability

The authors certify they have documented all data, methods, and materials used to conduct the research presented. Anonymized data pertaining to the research presented will be made available on reasonable request from external investigators.

Results

Participants' Characteristics and Follow-up Information

A total of 2,218 survivors of primary ICH who were alive at time of discharge from index ICH hospitalization and consented to longitudinal follow-up were screened for enrollment (figure 1). A total of 528 participants were excluded because they lacked longitudinal follow-up data due to either mortality within 90 days of ICH or loss to follow-up within 90 days of ICH. Compared to those with longitudinal follow-up data, excluded individuals were more likely to present with larger hematoma volumes and with lower educational attainment (both p < 0.05). In addition, a total of 768 patients across both studies either did not undergo MRI or did not have MRI data of sufficient quality obtained within 90 days of ICH and were therefore excluded. We found no significant differences in demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education), medical history (vascular risk factor, prior ICH, prior ischemic stroke or TIA), and ICH characteristics (volume, location, intraventricular extension) when comparing ICH survivors with and without MRI imaging data (all p > 0.20).

After application of all inclusion and exclusion criteria, 922 ICH survivors originally enrolled in the ERICH (n = 329) and MGH-ICH (n = 593) studies were included in subsequent analyses (table 2). Of these, 655 self-identified as White, 130 as Black, and 137 as Hispanic. Compared to survivors in ERICH, patients in the MGH-ICH study were more likely to be older, to be of self-reported White race/ethnicity, to have more years of education, and to report medical history of atrial fibrillation. ERICH patients were more likely to present with nonlobar ICH on initial CT scans and with HTNA-related ICH on MRI data. We followed up ERICH study participants for a median follow-up time of 18.2 months (interquartile range [IQR] 14.5–23.8 months). We lost to follow-up (for reasons other than death) 10 of 329 patients, corresponding to a rate of 3.2%/y. We identified 49 recurrent ICH events among ERICH study participants, for an estimated annual recurrence rate of 2.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2%–3.7%). We followed up MGH-ICH study participants for a median of 46.5 months (IQR 35.5–58.9 months). We identified 41 of 593 participants who were lost to follow-up (for reasons other than death), corresponding to a rate of 1.4%/y. We identified 62 ICH recurrence events among MGH-ICH study participants, corresponding to an estimated annual recurrence rate of 4.2% (95% CI 2.8%–6.5%).

Table 2.

Participants' Characteristics

Racial and Ethnic Variations in CSVD

Minority survivors displayed significantly higher values for the global CSVD score and HTNA-CSVD score, indicating greater severity of underlying microvascular disease (table 3). Among individual MRI markers, nonlobar lacunes, nonlobar CMBs, and BG EPVS were more prevalent among minority individuals, reflecting greater severity of HTNA (all p < 0.05, table 3). We subsequently investigated racial/ethnic differences in CAA and HTNA burden within individual ICH etiologic subtypes. As expected, CAA-related ICH had the highest CAA MRI score (median 2, IQR 1–3) in comparison (p = 0.028 for trend test across categories) with mixed-etiology ICH (median 1, IQR 0–2) and HTNA-related ICH (median 1, IQR 0–1). Minority individuals displayed lower CAA burden when presenting with CAA-ICH, while no differences in CAA burden existed across race/ethnic groups in patients with mixed-etiology and HTNA-related ICH (figure 2). HTNA burden on MRI gradually decreased (p = 0.009 for trend test across categories) moving from hypertensive ICH (median 2, IQR 1–3) to mixed-etiology ICH (median 2, IQR 1–2) and then to CAA-related ICH (median 0, IQR 0–1). Minority survivors of hypertensive and mixed-etiology ICH had greater HTNA burden than their White counterparts, while no racial/ethnic differences existed in hypertensive small vessel disease severity after CAA-ICH (figure 2).

Table 3.

MRI-Based Evaluation of CSVD Across Racial/Ethnic Groups Among Study Participants

Figure 2. CAA and HTNA Small Vessel Disease Severity Across Racial/Ethnic Groups.

Graph presents stacked column plots of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and hypertensive arteriopathy (HTNA) small vessel disease scores on MRI among survivors of CAA-related, HTNA-related, and mixed-etiology intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) cases with comparison between White and minority (Black or Hispanic) groups. For each score value, the column labels report the percentage of patients in the group of interest. Total sample size in each group is presented below the columns. Comparison of score distribution between White and minority participants in each group resulted in the p values presented above each pair of columns.

CSVD and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in ICH Recurrence

We next investigated whether racial/ethnic variations in CSVD were associated with previously identified disparities in ICH recurrence risk. In univariable models, both self-reported race/ethnicity and CSVD severity (global CSVD burden score) were associated with ICH recurrence risk (table 4). In addition, underlying CSVD subtype (as defined by ICH etiologic classification) was associated with ICH recurrence risk. Survivors of CAA-related ICH were at highest risk for recurrence (annual recurrence rate 6.1%, 95% CI 5.3%–7.0%), followed by survivors of mixed-etiology ICH (annual recurrence rate 3.9%, 95% CI 3.2%–4.5%) and then hypertensive ICH (annual recurrence rate 1.6%, 95% CI 1.1%–2.3%). Multivariable modeling (table 4) indicated that CSVD subtype and severity did not fully account for racial/ethnic disparities in ICH recurrence; self-reported Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity remained independently associated with higher recurrent hemorrhagic stroke risk (data available from Dryad, table e1: doi.org/10.5061/dryad.51c59zw7v).

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of ICH Recurrence Risk

We present in figure 3 the combined effect of race/ethnicity and CSVD severity on ICH recurrence risk. Minority ICH survivors were at higher risk for ICH recurrence than their White counterparts in both the high CSVD burden (subhazard ratio 1.73, 95% CI 1.16–2.58, p = 0.011) and the low CSVD burden (subhazard ratio 1.48, 95% CI 1.05–2.09, p = 0.031) groups. We found no evidence for an interaction between race/ethnicity status and CSVD severity (interaction p = 0.11). CSVD subtype also affected the association between race/ethnicity and ICH recurrence risk. Compared to White participants (data available from Dryad, table e2: doi.org/10.5061/dryad.51c59zw7v), minority ICH survivors were at increased risk for recurrent cerebral bleeding after both hypertensive ICH (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.13–2.78, p = 0.021) and mixed ICH (HR 1.63, 95% CI 1.08–2.46, p = 0.026). The association between non-White race/ethnicity and recurrent hemorrhagic stroke after CAA-related ICH was not significant (HR 1.33, 95% CI 0.97–1.82, p = 0.091).

Figure 3. ICH Recurrence Risk Based on Small Vessel Disease Severity and Race/Ethnicity.

Kaplan-Meier plot of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) recurrence risk across study sub-groups identified based on race/ethnicity, i.e., White vs Black or Hispanic, and cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) severity, defined using the global MRI burden score values as high burden (score >2) vs low burden (score 0–2). Cutoff global CSVD burden score value of 2 was selected because it represents the median value in the overall study dataset. Sample size in the study during follow-up is presented above the horizontal axis (marked n). *p < 0.01 for comparison of groups (log-rank test); **p < 0.001 for comparison of groups (log-rank test).

Discussion

We provide evidence that minority ICH survivors (i.e., of Black or Hispanic self-reported race/ethnicity) present with higher CSVD burden on MRI at the time of first ICH. This disparity contributes to higher risk of ICH recurrence among minority individuals. Our analyses specifically demonstrated greater severity of HTNA among minority ICH survivors. In turn, minority survivors of hypertensive and mixed-etiology ICH were at higher risk for recurrent bleeding compared to their White counterparts. Overall, our findings suggest the existence of racial and ethnic differences in underlying CSVD epidemiology among ICH survivors.

In agreement with previous studies, we confirmed that Black and Hispanic ICH survivors are at significantly higher risk for recurrent cerebral bleeding compared to their White counterparts. In a previous study, we identified significant differences in average systolic blood pressure and its variability between White and minority ICH survivors.7 However, we also demonstrated that differences in hypertension control after ICH did not fully account for racial/ethnic disparities in recurrence risk. The present analyses point to underlying CSVD subtype and severity as independent factors accounting for this health inequality. These findings will be critical in guiding future clinical and research efforts in the realm of secondary prevention after ICH. Specifically, the role of MRI-based CSVD evaluation in identifying at-risk minority ICH survivors deserves attention in future studies. As an example, our results warrant further investigation into whether CSVD burden, as determined by a validated rating score (e.g., global CSVD score23), could inform blood pressure control goals in patient groups at increased risk for recurrent ICH.

We also provide evidence that HTNA disease burden at baseline (i.e., time of index ICH) was greater among Black and Hispanic patients. MRI-based markers of HTNA (namely nonlobar CMB, nonlobar lacunar infarcts, and basal ganglia EPVS) were significantly more prevalent among Black and Hispanic patients compared to their White counterparts. In contrast, we did not find a significant difference in prevalence of neuroimaging markers of CAA across self-reported racial/ethnic groups. Given the known association between HTNA and hypertension,10 greater HTNA severity among minority ICH survivors may reflect disparities in hypertension control long predating the acute hemorrhagic event.29 Of note, minority survivors of hypertensive and mixed-etiology ICH presented with more severe HTNA on MRI at the time of ICH. In contrast, minority survivors of CAA-related ICH demonstrated lower CAA disease burden on MRI. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that APOE ε4 (an established genetic risk factor for CAA) increased risk for recurrent lobar hemorrhages among White but not minority ICH survivors.30 Taken together, these findings imply differences in CSVD epidemiology between White and minority ICH survivors, deserving of additional investigation in future studies. In-depth exploration of racial/ethnic differences in hypertension and CSVD epidemiology among survivors of ICH is limited by the nature of available data collected for participating individuals in our study. However, disparities in the prevalence and control of vascular risk factors, particularly hypertension, health care access, and socioeconomic factors at large, affect minority groups disproportionately.29,31,32 In turn, higher rates of inadequately treated blood pressure likely lead to chronic CSVD progression and ultimately ICH recurrence. A deeper understanding of the health disparities and social determinants of health contributing to uncontrolled hypertension and higher CSVD burden among minority ICH survivors will be critical to decrease the incidence of first-ever and recurrent ICH.

Our findings reinforce the importance of implementing secondary stroke prevention strategies aimed at minority ICH survivors, who are disproportionately affected by hemorrhage recurrence.7,33 Focusing on modifiable vascular risk factors previously associated with CSVD risk and progression (especially high blood pressure) may lower ICH recurrence risk among minority patients with high microvascular disease burden.10 We and other previously showed that hypertension control rates are low among ICH survivors and lower still among minority individuals.7 Secondary stroke prevention after ICH will therefore benefit from focusing clinical care on adequate antihypertensive management (focusing on drug selection, avoiding medication undertreatment, and encouraging medication adherence), regular outpatient follow-up, and lifestyle modifications (increased physical activity, dietary modification, smoking cessation, weight reduction).8

Our study has some limitations. First, the majority of enrollment sites for participating studies were tertiary care centers with expertise in ICH care. As a result, ICH survivors with more severe hemorrhages and higher CSVD burden may be overrepresented in our study population, resulting in severity bias. Second, not all ICH survivors eligible for enrollment underwent an MRI as part of either the MGH-ICH or ERICH study. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that more severe cases may have been systematically prevented from undergoing MRI scans, thus resulting in limited generalizability to ICH survivors at large. However, we found no significant differences between individuals who did and did not undergo MRI after ICH. Third, due to the nature of our study design, we are limited to describing associations between race/ethnicity, CSVD, and recurrent ICH, rather than being able to establish a definitive causal link. Fourth, we used self-reported race/ethnicity as a proxy for the complex network of partially overlapping biological, socioeconomic, and cultural traits associated with racial/ethnic background. Social and cultural aspects of racial/ethnic disparities in ICH are beyond the ability of our study to investigate in-depth and therefore deserve to be fully addressed in future studies.

Our study also displays several strengths. We were able to study a large sample of ethnically diverse ICH survivors with comparatively low loss to follow-up among both White and minority participants. In addition, ICH survivors in both studies underwent dedicated MRI and participated in longitudinal follow-up using highly compatible protocols. Although participants in the ERICH and MGH-ICH study differed considerably in their demographics, medical history, and ICH characteristics, we found highly consistent associations between race/ethnicity and CSVD across both studies. Our observations are therefore likely to be generalizable to ICH survivors at large. MRI scans were systematically evaluated by trained raters using validated methods for interpretation of CSVD-related markers. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing racial/ethnic disparities in CSVD severity and ICH recurrence risk.

We demonstrated that Black and Hispanic ICH survivors present with greater CSVD severity on MRI at the time of initial hemorrhagic stroke. In turn, this contributes to previously identified disparities in ICH recurrence risk. The HTNA CSVD subtype was more prevalent and more severe among minority ICH survivors, especially those presenting with hypertensive or mixed-etiology hemorrhages. Future studies of ICH survivors will benefit from incorporating MRI-based assessment of underlying CSVD and will need to focus on other potential contributors to racial/ethnic disparities in ICH recurrence, including social determinants of health.

Glossary

- BG

basal ganglia

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CI

confidence interval

- CMB

cerebral microbleed

- CSO

centrum semiovale

- cSS

cortical superficial siderosis

- CSVD

cerebral small vessel disease

- FDR

false discovery rate

- EPVS

enlarged perivascular spaces

- ERICH

Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- HTNA

hypertensive arteriopathy

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- IQR

interquartile range

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- SWI

susceptibility-weighted image

- T2*-GRE

T2*-weighted gradient recalled echo

- WMH

white matter hyperintensities

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

The authors' work on this study was supported by funding from the US NIH (K23NS100816, R01NS093870, R01NS103924, and R01AG26484).

Disclosure

J.P. Castello, M. Pasi, J.R. Abramson, A. Rodriguez-Torres, S. Marini, S. Demel, L. Gilkerson, P. Kubiszewski, A. Charidimou, C. Kourkoulis, Z. DiPucchio, K. Schwab, M.E. Gurol, C.D. Langefeld, M.L. Flaherty, A. Towfighi, and D. Woo report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S.M. Greenberg is supported by R01AG26484. A. Viswanathan is supported by P50AG005134. C.D. Anderson is supported by R01NS103924, AHA18SFRN34250007, and MGH received research support from Bayer AG and consulting fees from ApoPharma, Inc. J. Rosand is supported by R01NS036695, UM1HG008895, R01NS093870, and R24NS092983 and has consulted for New Beta Innovations, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer Inc. A. Biffi is supported by MGH and by K23NS100816. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Poon MT, Fonville AF, Al-Shahi Salman R. Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(6):660-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Perez A, Gaist D, Wallander MA, McFeat G, Garcia-Rodriguez LA. Mortality after hemorrhagic stroke: data from general practice (The Health Improvement Network). Neurology. 2013;81(6):559-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae H, Jeong D, Doh J, Lee K, Yun I, Byun B. Recurrence of bleeding in patients with hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;9(2):102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey RD, Hart RG, Benavente O, Pearce LA. Recurrent brain hemorrhage is more frequent than ischemic stroke after intracranial hemorrhage. Neurology. 2001;56(6):773-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biffi A, Anderson CD, Battey TW, et al. Association between blood pressure control and risk of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA. 2015;314(9):904-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casolla B, Moulin S, Kyheng M, et al. Five-year risk of major ischemic and hemorrhagic events after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;50(5):1100-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Torres A, Murphy M, Kourkoulis C, et al. Hypertension and intracerebral hemorrhage recurrence among White, Black, and Hispanic individuals. Neurology. 2018;91(1):e37-e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemphill JC IIIGreenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46(7):2032-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arima H, Tzourio C, Anderson C, et al. Effects of perindopril-based lowering of blood pressure on intracerebral hemorrhage related to amyloid angiopathy: the PROGRESS trial. Stroke. 2010;41(2):394-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannistraro RJ, Badi M, Eidelman BH, Dickson DW, Middlebrooks EH, Meschia JF. CNS small vessel disease: a clinical review. Neurology. 2019;92(24):1146-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(7):689-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasi M, Charidimou A, Boulouis G, et al. Mixed-location cerebral hemorrhage/microbleeds: underlying microangiopathy and recurrence risk. Neurology. 2018;90(2):e119-e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulouis G, Charidimou A, Pasi M, et al. Hemorrhage recurrence risk factors in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: comparative analysis of the overall small vessel disease severity score versus individual neuroimaging markers. J Neurol Sci. 2017;380:64-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rensma SP, van Sloten TT, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CDA. Cerebral small vessel disease and risk of incident stroke, dementia and depression, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehavioral Rev. 2018;90:164-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo D, Rosand J, Kidwell C, et al. The Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study protocol. Stroke. 2013;44(10):e120-e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasi M, Boulouis G, Fotiadis P, et al. Distribution of lacunes in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive small vessel disease. Neurology. 2017;88(23):2162-2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Med. 2012;22(3):276-282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazekas F, Barkhof F, Wahlund LO, et al. CT and MRI rating of white matter lesions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(13suppl 2):31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):165-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Pasi M, et al. MRI-visible perivascular spaces in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive arteriopathy. Neurology. 2017;88(12):1157-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Roongpiboonsopit D, et al. Cortical superficial siderosis multifocality in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a prospective study. Neurology. 2017;89(21):2128-2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau KK, Li L, Schulz U, et al. Total small vessel disease score and risk of recurrent stroke: validation in 2 large cohorts. Neurology. 2017;88(24):2260-2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charidimou A, Martinez-Ramirez S, Reijmer YD, et al. Total magnetic resonance imaging burden of small vessel disease in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: an imaging-pathologic study of concept validation. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(8):994-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staals J, Makin SD, Doubal FN, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Stroke subtype, vascular risk factors, and total MRI brain small-vessel disease burden. Neurology. 2014;83(14):1228-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linn J, Halpin A, Demaerel P, et al. Prevalence of superficial siderosis in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2010;74(17):1346-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keselman HJ, Cribbie R, Holland B. Controlling the rate of type I error over a large set of statistical tests. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2002;55(pt 1):27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh KB, Woo D, Sekar P, et al. Untreated hypertension: a powerful risk factor for lobar and nonlobar intracerebral hemorrhage in Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Circulation. 2016;134(19):1444-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marini S, Crawford K, Morotti A, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E with intracerebral hemorrhage risk by race/ethnicity: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(4):480-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutierrez J, Williams OA. A decade of racial and ethnic stroke disparities in the United States. Neurology. 2014;82(12):1080-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safford MM. Intracerebral hemorrhage, racial disparities, and access to care. Circulation. 2016;134(19):1453-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leasure AC, King ZA, Torres-Lopez V, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage recurrence. Neurology. 2020;94(3):e314-e322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors certify they have documented all data, methods, and materials used to conduct the research presented. Anonymized data pertaining to the research presented will be made available on reasonable request from external investigators.