Abstract

Background

Recent studies have reported weight gain in virologically suppressed persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) switched from older antiretroviral therapy (ART) to newer integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)–based regimens. In this study, we investigated whether weight gain differs among treatment-naive PLWH starting INSTI-based regimens compared to other ART regimens.

Methods

Adult, treatment-naive PLWH in the Vanderbilt Comprehensive Care Clinic cohort initiating INSTI-, protease inhibitor (PI)–, and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)–based ART between January 2007 and June 2016 were included. We used multivariable linear mixed-effects models to generate marginal predictions of weights over time, adjusting for baseline clinical and demographic characteristics. We used restricted cubic splines to relax linearity assumptions and bootstrapping to generate 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Among 1152 ART-naive PLWH, 351 initiated INSTI-based regimens (135 dolutegravir, 153 elvitegravir, and 63 raltegravir), 86% were male, and 49% were white. At ART initiation, median age was 35 years, body mass index was 25.1 kg/m2, and CD4+ T-cell count was 318 cells/μL. Virologic suppression at 18 months was similar between different ART classes. At all examined study time points, weight gain was highest among PLWH starting dolutegravir. At 18 months, PLWH on dolutegravir gained 6.0 kg, compared to 2.6 kg for NNRTIs (P < .05), and 0.5 kg for elvitegravir (P < .05). PLWH starting dolutegravir also gained more weight at 18 months compared to raltegravir (3.4 kg) and PIs (4.1 kg), though these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

Treatment-naive PLWH starting dolutegravir-based regimens gained significantly more weight at 18 months than those starting NNRTI-based and elvitegravir-based regimens.

Keywords: integrase strand transfer inhibitors, treatment-naive adults with HIV, weight gain, HIV metabolic complications

This report evaluates the differences in weight gain among treatment-naive persons living with HIV (PLWH) initiating antiretroviral therapy. The results highlight enhanced weight gain among PLWH starting dolutegravir-based therapy and lower weight gain with elvitegravir-based therapy.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Wood on pages 1275–7.)

The decrease in morbidity and mortality of persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) has been associated with a parallel increase in the rate of noncommunicable diseases, particularly metabolic disorders [1]. In PLWH the traditional metabolic disease risk factors of obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and genetic predisposition intersect with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–specific risk factors, including metabolic perturbations related to antiretroviral therapy (ART) [2]. The median body mass index (BMI) and prevalence of baseline obesity among PLWH initiating ART has been steadily increasing [3], with greater weight gain in the first year after initiating ART among women and patients with lower CD4+ T-cell count. Short-term weight gain following ART initiation has been associated with increased risk of diabetes [4–7] and cardiovascular disease [5]. This is particularly concerning, as nearly half of people in the United States living with diagnosed HIV are currently aged ≥50 years [8]. We recently reported that virologically suppressed PLWH on efavirenz-based regimens who switched to integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)–based regimens experienced significantly more weight gain compared to those who remained on efavirenz, and weight gain was greatest among those who switched to dolutegravir [9]. Several other studies have also investigated the association between INSTI-based regimens and weight gain. In AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) study A5260, a substudy of A5257, raltegravir was associated with similar changes in lean mass and regional fat at 96 weeks compared to ritonavir-boosted darunavir and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir [10]. However, raltegravir was associated with increased leg and arm fat, but not truncal fat, when compared to lopinavir/ritonavir in the study comparing lopinavir/ritonavir + emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with a nucleoside sparing regimen consisting of lopinavir/ritonavir + raltegravir (PROGRESS) study [11]. In observational studies, INSTI-based regimens generally [12], and dolutegravir-based regimens in particular [13], have been associated with accelerated weight gain. In a cohort from Brazil, PLWH receiving INSTI-based regimens were noted to be 7 times more likely to develop clinical obesity compared to those receiving nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)–based or PI-based regimens [12]. However, data comparing the weight gain between different INSTI drugs are limited.

In the current study, we sought to evaluate short-term weight gain among treatment-naive PLWH starting ART. We also aim to explore differences in short-term weight gain between different INSTI drugs and between these drugs and other PI- and NNRTI-based regimens.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of adults (aged ≥18 years) enrolled in care at the Vanderbilt Comprehensive Care Clinic, an outpatient HIV clinic in Nashville, Tennessee. The study cohort included all ART-naive patients, defined as having no prior history of any antiretroviral agent exposure, who initiated treatment between 1 January 2007 and 30 June 2016. Women who were pregnant at the time of ART initiation or became pregnant at any time during the study period were excluded. We also excluded patients who stopped or switched their initial ART regimen within the first 6 months of starting therapy. Patient weight was determined at routine clinic visits using a single measurement on the same mechanical scale. Clinical data were collected from an electronic medical record, which recorded patient encounter data including laboratory results. Research staff systematically extracted and validated all laboratory and clinical data, including medication start and stop dates, from the electronic medical record.

Data collected included weight, height, age at ART initiation, sex, race, duration from diagnosis of HIV infection to treatment, year of ART initiation, and treatment regimen, as well as pre– and post–ART initiation CD4+ T-cell lymphocyte count and plasma HIV type 1 (HIV-1) RNA measurements. Body weight nearest to ART initiation within the period from 180 days before to 30 days after treatment start was used to calculate baseline weight and BMI (kg/m2). Similarly, CD4 T-cell count and plasma HIV-1 RNA measurements nearest to ART initiation were used to define baseline levels. The absolute change in weight was defined as the difference between each subsequent weight measurement and baseline weight. Weight measurements were included from 1 year prior to study start date to 18 months following the predefined study end date.

Prevalence of virologic suppression, defined as having a viral load <200 copies/mL, was evaluated for all patients included in the study at 6 weeks and 3, 6, and 18 months. We assessed whether prevalence of virologic suppression, at these predefined time points, differed by ART class and individual INSTI drugs. Additionally, we evaluated whether virologic failure, defined as having a viral load of >1000 copies/mL after previously achieving virologic suppression, differed by ART classes or INSTI drugs.

The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board, and the requirement for an informed consent was waived. All patient records and pertinent information were de-identified prior to the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We compared patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics across different ART regimens, as well as across different INSTI antiretrovirals, using Pearson χ2, Wilcoxon rank-sum, or Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate. We used multivariable linear mixed-effects models to generate marginal predictions of weight over time, adjusting for age; sex; race; HIV acquisition mode; ART initiation year; and baseline weight, HIV-1 RNA, and CD4 T-cell count. We used restricted cubic splines to relax linearity assumptions for all continuous covariates and bootstrapping with 200 replicates to generate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the marginal predictions. Predicted weights by ART class were reported at 3-month intervals between 6 and 18 months.

Patients who completed at least 6 months of uninterrupted treatment with initial ART regimen were assigned to and analyzed by that class. Records from patients who were initiated on INSTI-based regimens were reviewed to identify any switches between different INSTI drugs.

Furthermore, we evaluated in a multivariable logistic regression model whether different ART regimens were associated with significantly different risk for incident obesity. In this model, we only included patients with baseline BMI <30 kg/m2 and evaluated the relative odds of incident obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) by regimen class within the follow-up period. The model was adjusted for baseline demographic (age, sex, race, and year of ART initiation) and clinical (baseline CD4 cell count, baseline viral load, and baseline BMI) variables. NNRTIs were used as the reference group.

All analyses were conducted in R version 3.4.3 and StataSE 15 software.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 1152 patients were included in the analysis. Of these, 454 (39%) started PI-based regimens whereas 347 (31%) started NNRTI-based and 351 (30%) started INSTI-based regimens. Among those starting INSTI-based regimens, 63 of 351 (18%) patients started raltegravir, while 153 of 351 (44%) and 135 of 351 (39%) started elvitegravir and dolutegravir, respectively. The most commonly used ART combinations among PLWH starting NNRTI-, PI-, and INSTI-based regimens are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine constituted the nucleoside backbone for the majority of NNRTI-, PI-, elvitegravir-, and raltegravir-based regimens. Meanwhile, abacavir and lamivudine were the predominant nucleoside backbone for the dolutegravir-based regimens. Most PI-based regimens were ritonavir-boosted and all the elvitegravir-based regimens were cobicistat-boosted.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were men. The median age of ART initiation was significantly lower among patients starting elvitegravir and dolutegravir. A higher proportion of women started PI-based regimens compared to men. The median baseline CD4+ T-cell count at time of ART initiation was higher among patients starting INSTI-based regimens, especially in those starting elvitegravir and dolutegravir. The median baseline HIV-1 RNA at time of ART initiation was 4.4 log10 copies/mL, with the lowest levels in those starting elvitegravir and the highest in those starting dolutegravir. Patients starting PI-based regimens had significantly lower baseline weight compared to other ART classes. NNRTI and PI-based regimens were more commonly used prior to 2013, whereas INSTI-based regimens were predominant from 2014 onward. Among INSTIs, elvitegravir-based combination ART was the most commonly prescribed in 2014 to early 2015, after which it was surpassed by dolutegravir-based combination ART. Regimen distribution by year is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The variation of baseline BMI and CD4 T-cell count by year of ART initiation are shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Observed baseline BMI (mean ± standard deviation) increased from 25.7 ± 5.7 kg/m2 in 2007 to 27.7 ± 7.1 kg/m2 in 2016, with an increase in the prevalence of baseline obesity (defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2) from 19% in 2007 to 34% in 2016. In contrast, baseline CD4+ T-cell count steadily increased over the study period. Patients with baseline CD4+ T-cell count <200 cells/µL dropped from 54% in 2007 to 19% in 2016.

Table 1.

Distribution of Study Patients by Regimen Class

| Factor | All Regimens | NNRTI-based Regimens | PI-based Regimens | INSTI-based Regimens | P Valuea | Raltegravir | Elvitegravir | Dolutegravir | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, No. (%) | 1152 | 347 (30.5) | 454 (39.4) | 351 (30.1) | 63 (17.9) | 153 (43.6) | 135 (38.5) | |||

| Age at time of ART initiation, y, median (IQR) | 35 (27–44) | 38 (29–45) | 36 (26–44) | 33 (26–43) | .002 | 38 (28–46) | 32 (25–40) | 33 (25–45) | .01 | |

| Birth sex | Male | 985 (85.5) | 310 (88.3) | 306 (88.2) | 369 (81.3) | .005 | 54 (85.7) | 140 (91.5) | 116 (85.9) | .26 |

| Female | 167 (14.5) | 41 (11.8) | 85 (18.7) | 41 (11.7) | 9 (14.3) | 13 (8.5) | 19 (14.1) | |||

| Race group | White | 559 (48.5) | 169 (48.1) | 189 (54.5) | 201 (44.3) | 38 (60.3) | 72 (47.1) | 59 (43.7) | ||

| Black | 484 (42.0) | 124 (35.7) | 216 (47.6) | 144 (41.0) | .01 | 19 (30.2) | 65 (42.5) | 60 (44.4) | .28 | |

| Other | 109 (9.5) | 34 (9.8) | 37 (8.1) | 38 (10.8) | 6 (9.5) | 16 (10.5) | 16 (11.9) | |||

| Baseline CD4 T-cell count, cells/µL, median (IQR) | 318 (159–469) | 291 (144–440) | 282 (127–427) | 401 (234–594) | <.001 | 302 (117–451) | 453 (288–657) | 380 (241–591) | <.001 | |

| Baseline log HIV RNA, copies/mL, median (IQR) | 4.4 (3.4–5.0) | 4.5 (3.3–5.0) | 4.5 (3.7–5.1) | 4.4 (3.0–4.9) | .002 | 4.6 (3.9–5.1) | 4.2 (2.5–4.7) | 4.5 (3.2–5.0) | .008 | |

| Baseline weight, kg, median (IQR) | 76.8 (67.1–87.9) | 77.6 (68.0–88.5) | 75.4 (66.4–86.0) | 78.1 (67.3–91.9) | .02 | 79.4 (70.2–86.6) | 77.6 (65.8–92.5) | 78.0 (67.2–96.2) | .84 | |

| Year of ART initiation, median (IQR) | 2011 (2009–2014) | 2010 (2008–2011) | 2011 (2009–2012) | 2014 (2014–2015) | <.001 | 2010 (2010–2012) | 2014 (2014–2015) | 2015 (2015–2016) | <.001 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

aComparing the difference in baseline characteristics by regimen class (INSTI-, NNRTI-, and PI-based regimens).

bComparing the difference in baseline characteristics by class of integrase inhibitor (raltegravir, elvitegravir, and dolutegravir).

None of the patients initiated on dolutegravir-, elvitegravir-, or raltegravir-based regimens switched their regimen during the study period.

Virologic Suppression

Among all PLWH, 350 (30.4%) achieved virologic suppression by 6 weeks, and viral suppression at 3, 6, and 18 months was 60.2%, 87.2%, and 97.3%, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Patients starting INSTIs were significantly more likely to be virally suppressed early after treatment initiation (at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months). However, by the end of the study follow-up, the rates of viral suppression were similar across all ART regimens. There was no difference in rates of viral suppression throughout the study period between INSTI-based regimens (Supplementary Table 2).

A total of 74 patients (6.4%) had virologic failure during study follow-up (Supplementary Table 2). Prevalence of virologic failure was significantly higher among PLWH starting a PI (41/145 [9.0%]) than among those starting an NNRTI (13/347 [3.7%]) or INSTI (20/351 [5.7%]). Proportions with virologic failure were similar across the different INSTI drugs (Supplementary Table 2).

Weight Gain

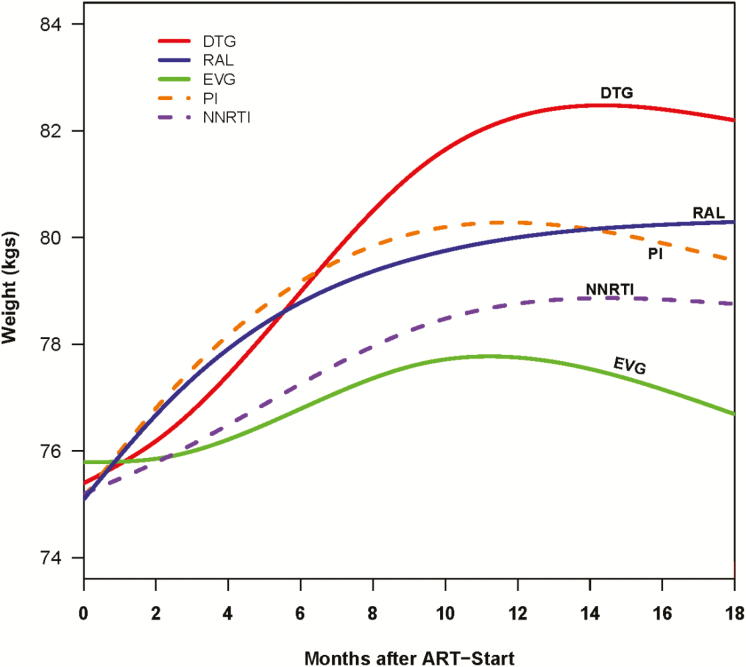

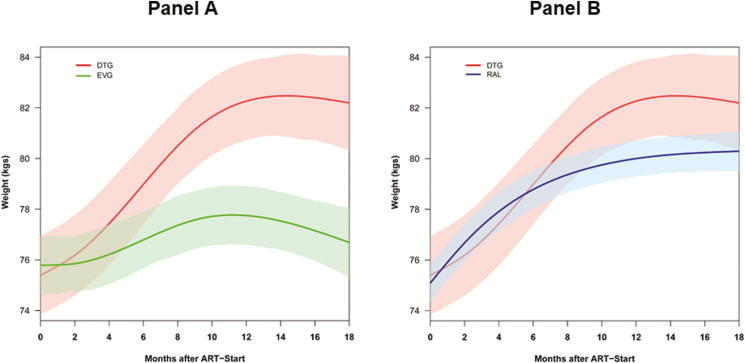

All patients had substantial weight gain within the first year of starting ART, after which time the rate of weight gain slowed. The predicted changes in weight over time by treatment regimen from our multivariable model are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3. Overall, the adjusted average weight gain was 2.4 kg (95% CI, 1.0–3.7 kg) at 6 months and 3.9 kg (95% CI, 2.4–5.4 kg) at 18 months. Among INSTIs, adjusted average weight gain varied by individual drug, with patients on dolutegravir gaining more weight than those on elvitegravir or raltegravir (Figure 2). Dolutegravir-based regimens were associated with adjusted average weight gain of 2.9 kg and 6.0 kg at 6 and 18 months, respectively, which was significantly higher than the adjusted average weight gain associated with elvitegravir at these time points (0.6 kg and 0.5 kg, respectively). The adjusted average weight gain associated with raltegravir-based regimens at 6 and 18 months (3.0 kg and 3.4 kg, respectively) was significantly higher than that with elvitegravir, but not significantly different than the adjusted average weight gain associated with dolutegravir (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1.

Changes in weight within 18 months of treatment initiation among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus, by antiretroviral regimen. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DTG, dolutegravir; EVG, elvitegravir; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; RAL, raltegravir.

Figure 2.

Changes in weight within 18 months of treatment initiation among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus starting dolutegravir and elvitegravir (A) or dolutegravir and raltegravir (B). Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DTG, dolutegravir; EVG, elvitegravir; RAL, raltegravir.

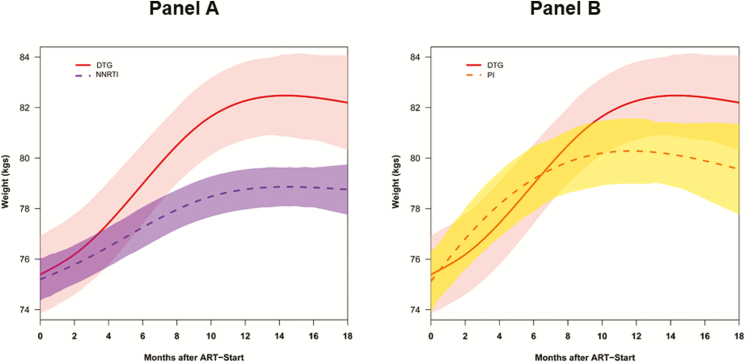

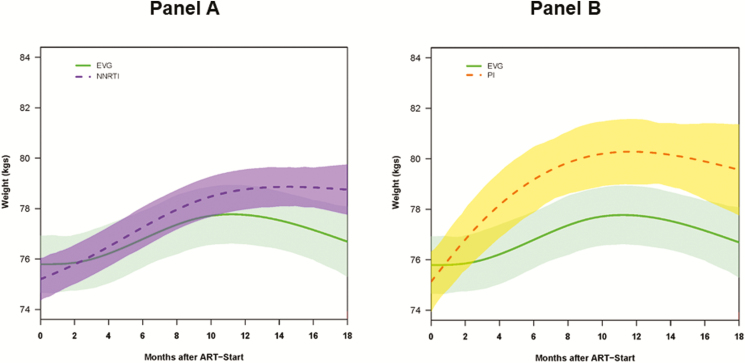

At 6 and 18 months, NNRTI-based regimens were associated with adjusted average weight gains of 1.1 kg and 2.6 kg, respectively; at 18 months, weight gain on NNRTI-based regimens was significantly lower compared to dolutegravir-based regimens (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3). The adjusted average weight gain associated with NNRTI-based regimens was not significantly different compared to elvitegravir-based regimens (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in weight within 18 months of treatment initiation among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus starting dolutegravir and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (A) or dolutegravir and protease inhibitors (B). Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DTG, dolutegravir; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

Figure 4.

Changes in weight within 18 months of treatment initiation among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus starting elvitegravir and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (A) or elvitegravir and protease inhibitors (B). Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; EVG, elvitegravir; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

In comparison, PI-based regimens were associated with 2.6 kg and 4.1 kg weight gains at 6 and 18 months, respectively. PI-based regimens were associated with significantly higher weight gain compared to that seen with elvitegravir-based regimens (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 3). While PI-based regimens were associated with lower weight gain compared to dolutegravir-based regimens, the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3).

Moreover, neither sex nor race had a significant effect on weight gain. In our adjusted models, weight gain among women was, on average, 0.4 kg (95% CI, –2.1 to 1.4) lower than that among men. Additionally, weight gain among black patients was, on average, 0.1 kg (95% CI, –1.1 to 1.3) higher than weight gain among whites and other races.

Among PLWH with BMI <30 kg/m2, the odds of incident obesity during study follow-up did not differ by ART regimen. Nevertheless, dolutegravir-based regimens were associated with the highest, albeit non–statistically significant, odds of incident obesity (odds ratio, 1.6 [95% CI, .6–4.4]).

DISCUSSION

Our observational analysis is the first to explore differences in short-term weight gain following treatment initiation among different INSTI drugs and between INSTI-, PI-, and NNRTI-based regimens. Our findings highlight the variation in short-term weight gain among ART-naive PLWH starting INSTI-based regimens according to the INSTI drug used. We observed that PLWH starting dolutegravir- and raltegravir-based regimens gained significantly more weight compared to persons starting elvitegravir-based regimens. Additionally, PLWH starting dolutegravir-based regimens gained significantly more weight at 18 months compared to persons starting NNRTI-based regimens. Those on dolutegravir-based regimens also gained more weight than persons initiating PI-based regimens, but the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, elvitegravir-based regimens were associated with the least short-term weight gain. PLWH starting elvitegravir-based regimens gained significantly less weight than persons starting PI-, dolutegravir-, and raltegravir-based regimens.

Initiation of ART among treatment-naive PLWH is often associated with a short period of weight gain, especially among patients with low baseline BMI, those with profound depletion of CD4 T cells, and high baseline HIV-1 RNA viral load [10, 14–16]. In the early ART era, weight gain among PLWH was associated with improved immunologic recovery and better survival [14, 17–20]. Therefore, early in the clinical experience of treating PLWH when untreated patients suffered from cachexia and wasting, weight gain following ART initiation was seen as part of the “return to health” phenomenon. This phenomenon was thought to be a direct result of successfully suppressing viral replication, controlling inflammation, and normalizing resting energy expenditure [21]. However, obesity is increasingly prevalent among PLWH initiating ART [3]. By 2016, one-third of the patients starting ART in our study were obese and more than half had a BMI higher than normal (≥25 kg/m2). In the context of higher pretreatment BMI among patients starting ART in the current era, short-term weight gain after ART initiation may represent an undesirable effect that is placing patients at higher risk for cardiovascular and metabolic complications. In a recent study, short-term gain in BMI following ART initiation appeared to increase the longer-term risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes compared to HIV-negative persons [5, 6]. Additionally, weight gain following ART initiation has been associated with worsening of 2 key risk factors for cardiovascular disease among overweight and obese patients: dyslipidemia [22] and systemic inflammation [23]. This is especially concerning as PLWH are already at a higher risk of hypertension [24], myocardial infarction [24–28], peripheral arterial disease [24, 29], and impaired renal function [24, 30] compared to the general population.

In our study, weight gain varied between ART regimens after controlling for several baseline clinical and demographic characteristics that have been previously associated with higher BMI gain following treatment initiation (ie, sex, baseline BMI, CD4+ T-cell count, and HIV-1 viral load) [10, 14, 16]. One variable we did not adjust for was the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) backbone. In our cohort, most patients who received dolutegravir had abacavir/lamivudine as the NRTI backbone whereas tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine was the NRTI backbone used with the majority of other INSTI, NNRTI, and PI medications. However, in light of previously published studies, we do not expect for the NRTI backbone to have significant effects on weight gain. In the ACTG study A5224s, a substudy of A5202, changes in weight, BMI, and lean body mass were not statistically different between PLWH receiving ART with abacavir/lamivudine NRTI backbone, compared to those receiving ART with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine NRTI backbone [31]. Moreover, changes in insulin resistance were also similar among ART-naive patients randomized to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine vs an abacavir/lamivudine–based regimen [32].

The mechanism explaining the difference noted in weight gain among INSTI-based regimens and between these regimens and NNRTI- or PI-based regimens is unknown. One possible explanation is the rapid drop in viral load seen with INSTI-based regimens and the correlation of virologic suppression with lower energy expenditure [33]. However, we did not observe a marked difference in rates of virologic suppression between dolutegravir- and elvitegravir-based regimens at the time points examined. Another possible mechanistic explanation is differences in inflammatory biomarkers, and potentially related catabolic processes, between regimens. As an example, switching from PI-based regimens to a raltegravir-based regimen has been associated with statistically significant decline in soluble CD14 [34], a monocyte activation marker, as well as a decrease in levels of other systemic inflammatory biomarkers (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, tumor necrosis factor–α, and D-dimer) [35]. However, this hypothesis falls short of explaining the difference in weight gain noted between raltegravir and dolutegravir when compared to elvitegravir, especially in that the latter has also been associated with decrease in plasma levels of systemic, vascular, and monocyte activation biomarkers [36]. Other plausible hypotheses include possible differential effects of ART regimens on systems regulating energy homeostasis and food intake and on insulin resistance. For example, in vitro dolutegravir has been shown to affect the activity of melanocyte-stimulating hormone, a family of peptide hormones and neuropeptides involved in appetite control. Therefore, increased appetite with dolutegravir could be a plausible explanation for the higher weight gain noted with this drug [37]. Moreover, further studies are needed to evaluate whether secondary effects of cobicistat, the pharmacologic enhancer used with all the elvitegravir-based regimens, could explain the lower weight gain seen with this regimen.

Our study had several limitations. It was a retrospective analysis of a predominantly male cohort from a single center in the southeastern United States; the results may therefore not be generalizable to other populations. Based on the recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of dolutegravir in August 2014, we limited our analysis window to 18 months to reduce data sparseness over a longer time period. Additionally, patients who initiated and completed 6 months of therapy with a treatment regimen were assigned and analyzed to that class without accounting for the possibility of regimen switches during the 18-month follow-up. However, as mentioned in the results, none of the patients who were assigned and analyzed in either the raltegravir, elvitegravir, or dolutegravir groups had switched classes during the study period. Moreover, we did not have data regarding patients’ caloric intake or physical activity levels. We also did not account for concomitant medication usage that may have caused weight changes (ie, metformin, psychiatric medications). Furthermore, to ensure adequate follow-up, we limited our study to patients who initiated ART prior to 1 July 2016 and therefore did not include any patients on bictegravir, approved by the FDA in February 2018, or tenofovir alafenamide, approved in November 2016.

While our results highlight the association between dolutegravir and increased weight gain among treatment-naive patients, the impact of our findings on clinical practice are, as yet, unclear. A central question is whether the increased weight gain on dolutegravir is related to off-target effects of the medication on energy storage and adipose tissue accumulation, as opposed to greater antiviral efficacy resulting in lower basal energy expenditure in the setting of HIV infection. Similarly, the impact of the increased weight gain on metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes is unclear at this time. Until additional studies can clarify the mechanisms related to differences in weight gain on different ART regimens, the patient characteristics associated with the greatest weight change, and the impact of the increased weight gain, we believe clinicians should continue utilizing dolutegravir if it represents the best choice for a patient given other factors.

In summary, short-term weight gain following ART initiation varied among the different INSTIs. Patients starting dolutegravir-based regimens were at the highest risk for short-term weight gain; in contrast, weight gain was minimal among those starting elvitegravir-based regimens. Future multicenter cohort studies and randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm our findings in addition to evaluating potential mechanisms linking antiretroviral agents and body weight changes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the Tennessee Center for AIDS Research (grant number P30 AI110527).

Potential conflicts of interest. P. F. R. and J. R. K. have received grant funding through an investigator-sponsored research grant from Gilead Sciences. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Wong C, Gange SJ, Moore RD, et al. North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) . Multimorbidity among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:1230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lake JE, Currier JS. Metabolic disease in HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:964–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Lau B, et al. North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) . Rising obesity prevalence and weight gain among adults starting antiretroviral therapy in the United States and Canada. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016; 32:50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Isa SE, Oche AO, Kang’ombe AR, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus and risk of type 2 diabetes in a large adult cohort in Jos, Nigeria. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:830–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Achhra AC, Mocroft A, Reiss P, et al. D:A:D Study Group . Short-term weight gain after antiretroviral therapy initiation and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: the D:A:D study. HIV Med 2016; 17:255–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herrin M, Tate JP, Akgun KM, et al. Weight gain and incident diabetes among HIV-infected veterans initiating antiretroviral therapy compared with uninfected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73:228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Justman JE, Benning L, Danoff A, et al. Protease inhibitor use and the incidence of diabetes mellitus in a large cohort of HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003; 32:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, vol. 29. 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed 1 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Norwood J, Turner M, Bofill C, et al. Brief report: weight gain in persons with HIV switched from efavirenz-based to integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 76:527–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McComsey GA, Moser C, Currier J, et al. Body composition changes after initiation of raltegravir or protease inhibitors: ACTG A5260s. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:853–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reynes J, Trinh R, Pulido F, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir combined with raltegravir or tenofovir/emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive subjects: 96-week results of the PROGRESS study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29:256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bakal DR, Coelho LE, Luz PM, et al. Obesity following ART initiation is common and influenced by both traditional and HIV-/ART-specific risk factors. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73:2177–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Menard A, Meddeb L, Tissot-Dupont H, et al. Dolutegravir and weight gain: an unexpected bothering side effect? AIDS 2017; 31:1499–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuh B, Tate J, Butt AA, et al. Weight change after antiretroviral therapy and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1852–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lakey W, Yang LY, Yancy W, Chow SC, Hicks C. Short communication: from wasting to obesity: initial antiretroviral therapy and weight gain in HIV-infected persons. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29:435–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Lau B, et al. Body mass index and early CD4 T-cell recovery among adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in North America, 1998–2010. HIV Med 2015; 16:572–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koethe JR, Limbada MI, Giganti MJ, et al. Early immunologic response and subsequent survival among malnourished adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in urban Zambia. AIDS 2010; 24:2117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koethe JR, Lukusa A, Giganti MJ, et al. Association between weight gain and clinical outcomes among malnourished adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53:507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Madec Y, Szumilin E, Genevier C, et al. Weight gain at 3 months of antiretroviral therapy is strongly associated with survival: evidence from two developing countries. AIDS 2009; 23:853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paton NI, Sangeetha S, Earnest A, Bellamy R. The impact of malnutrition on survival and the CD4 count response in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2006; 7:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tate T, Willig AL, Willig JH, et al. HIV infection and obesity: where did all the wasting go? Antivir Ther 2012; 17:1281–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maia Leite LH, De Mattos Marinho Sampaio AB. Progression to overweight, obesity and associated factors after antiretroviral therapy initiation among Brazilian persons with HIV/AIDS. Nutr Hosp 2010; 25:635–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mave V, Erlandson KM, Gupte N, et al. ACTG PEARLS and NWCS 319 Study Team . Inflammation and change in body weight with antiretroviral therapy initiation in a multinational cohort of HIV-infected adults. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, et al. AGEhIV Cohort Study Group . Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1787–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Drozd DR, Kitahata MM, Althoff KN, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected individuals in North America compared with the general population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 75:568–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klein DB, Leyden WA, Xu L, et al. Declining relative risk for myocardial infarction among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative individuals with access to care. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1278–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, et al. French Hospital Database on HIV-ANRS CO4 . Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS 2010; 24:1228–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beckman JA, Duncan MS, Alcorn CW, et al. Association of human immunodeficiency virus infection and risk of peripheral artery disease. Circulation 2018; 138:255–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Overton ET, Nurutdinova D, Freeman J, Seyfried W, Mondy KE. Factors associated with renal dysfunction within an urban HIV-infected cohort in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2009; 10:343–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Erlandson KM, Kitch D, Tierney C, et al. Weight and lean body mass change with antiretroviral initiation and impact on bone mineral density. AIDS 2013; 27:2069–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erlandson KM, Kitch D, Tierney C, et al. Impact of randomized antiretroviral therapy initiation on glucose metabolism. AIDS 2014; 28:1451–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mulligan K, Tai VW, Schambelan M. Energy expenditure in human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:70–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lake JE, McComsey GA, Hulgan T, et al. Switch to raltegravir decreases soluble CD14 in virologically suppressed overweight women: the women, integrase and fat accumulation trial. HIV Med 2014; 15:431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martínez E, Polyana M, Llibre JM, et al. Changes in cardiovascular biomarkers in HIV-infected patients switching from ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors to raltegravir. AIDS 2012; 26:2315–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hileman CO, Kinley B, Scharen-Guivel V, et al. Differential reduction in monocyte activation and vascular inflammation with integrase inhibitor-based initial antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:345–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hill A, Waters L, Pozniak A. Are new antiretroviral treatments increasing the risks of clinical obesity? J Virus Erad 2019; 5:41–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.