Abstract

The stimulator of interferon gene (STING) pathway controls both DNA and RNA virus infection. STING is essential for induction of innate immune responses during DNA virus infection, while its mechanism against RNA virus remains largely elusive. We show that STING signaling is crucial for restricting chikungunya virus infection and arthritis pathogenesis. Sting-deficient mice (Stinggt/gt) had elevated viremia throughout the viremic stage and viral burden in feet transiently, with a normal type I IFN response. Stinggt/gt mice presented much greater foot swelling, joint damage, and immune cell infiltration than wild-type mice. Intriguingly, expression of interferon-γ and Cxcl10 was continuously upregulated by approximately 7 to 10-fold and further elevated in Stinggt/gt mice synchronously with arthritis progression. However, expression of chemoattractants for and activators of neutrophils, Cxcl5, Cxcl7, and Cxcr2 was suppressed in Stinggt/gt joints. These results demonstrate that STING deficiency leads to an aberrant chemokine response that promotes pathogenesis of CHIKV arthritis.

Keywords: stimulator of interferon genes, STING, arthritogenic, alphavirus, chikungunya, viral, arthritis

Using a mouse model, we found that Sting deficiency resulted in increased chikungunya virus infection, inflammation in the footpad and joint, as well as interferon-γ and Cxcl10 expression in the joint.

Arthritogenic alphaviruses are transmitted by mosquitoes and pose a public health threat in the tropical/subtropical regions. Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is the causative agent of acute and chronic crippling arthralgia that reemerged on the Indian Ocean Islands in 2005–2006. Since late 2013, a new wave of CHIKV epidemics has taken place in the Americas, resulting in over 2.5 million infection cases in more than 40 countries (source, Pan America Health Organization) [1]. Approximately 50% of CHIKV-infected patients suffer from rheumatic manifestations that last 6 months to a year, whereas another approximately 5% of patients may have rheumatoid arthritis-like illness [2]. However, no licensed vaccines or specific antiviral therapeutics are available. This is partly due to an incomplete understanding of the protective and detrimental immune responses elicited by CHIKV. The type I interferon (IFN-I) system is clearly a critical early antiviral mechanism [3], while the antibody response is essential for viral clearance later [4]. However, the CHIKV viremia levels are not predictive of arthritis severity. For instance, even with heightened and prolonged viremia, B/T-cell deficient mice presented similar arthritic disease as wild type (WT) [5]. Of note, chronic CHIKV arthritis may progress without active viral replication [6].

The stimulator of interferon genes (STING) participates in innate immunity to both DNA and RNA viruses. During DNA virus infection, STING senses a second messenger cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which is synthesized by a viral DNA receptor, cGAMP synthase (cGAS) [7–9], leading to IFN-I expression. Our study with West Nile virus and other recent reports conclusively demonstrate that STING is also important for the control of RNA virus infection in mouse models [7, 10–12]; the underlying molecular mechanism, however, remains largely unclear. Several mechanisms of action have been proposed for STING during RNA virus infection. STING may cross-talk to retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) [7] or phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K) [13] to induce IFN-I. It may also sustain RIG-I signaling [14] at late stages of infection. Certain RNA virus infections, such as dengue virus, may damage mitochondria, which results in DNA leakage and activates the cGAS-STING pathway [15]. The cGAS-STING pathway may also be important to maintain a low basal level of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) as a sentinel against invading viruses [16]. Alternatively, STING could initiate IFN-I–independent antiviral actions, such as the adaptive immune response in the central nervous system [17], induction of a specific set of chemokines through signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) [12], and inhibition of viral protein translation [18]. Here we study the physiological function of STING in the pathogenesis of CHIKV. Sting-deficient mice have high viral loads and exacerbated arthritis, along with a normal IFN-I response. These mice also have higher expression of IFN-γ and Cxcl10 in the joints than WT.

METHODS

Mice

Wild-type C57BL/6J (JAX Stock number 000664) and Sting mutant (Stinggt/gt on C57BL/6 background, JAX Stock number 017537) breeders were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, sex and age (range 6–12 weeks)-matched mice were used for all the experiments. The animal protocol was approved and performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Connecticut Health Center and Yale University.

Reagents and Antibodies

The rabbit anti-GAPDH (catalogue number 5174), anti-STING (catalogue number 13647) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The mouse anti-OAS1a (catalogue number sc-365357) and rabbit anti-ISG56 (catalogue number sc-134949) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The rat anti-CD45 (catalogue number 103101), AF488 rat anti-Ly6C (catalogue number 128021), and AF 488 rat anti-F4/80 (catalogue number 123119) were purchased from BioLegend.

Cells and Viruses

Vero cells (monkey kidney epithelial cells, catalogue number CCL-81) and L929 (mouse fibroblasts, catalogue number CCL-1) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. These cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Corning). These cell lines are not listed in the database of commonly misidentified cell lines maintained by the International Cell Line Authentication Committee, and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination in our hands. To ensure cell culture mycoplasma free, we regularly treated cells with MycoZap (Lonza). Bone marrows were isolated from the tibia and femur bones and then differentiated into macrophages (BMDMs) in conditioned RPMI1640 (20% FBS, 30% L929-conditioned medium, antibiotics/antimycotics) in Petri dishes at 37°C for 5 days. The attached BMDMs were cultured in tissue-culture treated plastic wares in regular RPMI1640 medium (10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin) overnight before further treatment. The CHIKV French La Reunion strain LR2006-OPY1 was a kind gift of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven, CT.

Plaque-Forming Assay

Quantification of infectious viral particles in cell culture supernatants/mouse tissue homogenates/mouse sera was performed on a Vero cell monolayer in a 6-well plate following an established protocol [19]. A serial of 10-fold dilutions of viral samples was prepared in DMEM without fetal bovine serum. In a 6-well plate, 500 µL of diluted samples were added to a Vero monolayer. The plate was incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 hours. The inoculum was then removed and replaced with 2 mL of complete DMEM medium with 1% SeaPlaque agarose (Lonza). The plate was incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 days, and plaques were visualized by a Neutral Red exclusion assay. The viral loads from footpads were normalized by tissue mass (gram).

Mouse Infection and Disease Monitoring

CHIKV, 3 × 105 plaque-forming units (PFUs), was inoculated subcutaneously in the mouse hind footpad. Foot swelling as an indicator of inflammation was recorded over a period of 8 days after infection. The thickness and width of the perimetatarsal area of the hind foot were measured using a precision digital metric caliper in a blinded fashion. The foot dimension was calculated as width × thickness, and the results were expressed as fold increase in the foot dimension after infection compared to before infection (day 0 baseline). For histology, footpads/joints were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified, and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Arbitrary arthritic disease scores (on a 1–5 scale with 1 being the lightest, 5 the worst) were assessed using a combination of histological parameters, including exudation of fibrin and inflammatory cells into the joints, alteration in the thickness of tendons or ligament sheaths, and hypertrophy and hyperlexia of the synovium [20] in a double-blinded manner. Slides were imaged using an Accu-Scope EXI-310 inverted microscope with Infinity Capture software.

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from blood samples and footpad tissues using a RNAasy mini-prep kit (Invitrogen) and converted into cDNA using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed with gene-specific primers and iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The primers for CHIKV were forward primer (5′-GCGAATTCGGCGCAGCACCAAGGACAACTTCA-3′) and reverse primer (5′-AATGCGGCCGCCTAGCAGCATATTAGGCTAAGCAGG-3′). The housekeeping gene control used was β-actin (Actb). The results were calculated using the –∆∆ threshold cycle (Ct) method. The qPCR primers and probes for immune genes were reported in our previous studies [21].

PCR Array

Total RNA was extracted from white blood cells or skinned ankle joints, and reverse-transcribed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). The cDNA was used for the real-time RT Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen) in combination with SYBR Green qPCR master mix. Delta Ct (threshold cycle of qPCR) was the difference between the gene of interest and an average of 5 reference genes (Actb, B2m, Gapdh, Gusb, and Hsp90ab1). Fold change was then calculated using formula 2^ −∆∆Ct [∆Ct (Stinggt/gt) − ∆Ct (WT)].

RNASeq and Data Analysis

For sample preparation, 2 × 106 bone marrow-derived WT and Stinggt/gt macrophages were infected with CHIKV at a multiplicity of infection of 5 for 12 hours or mock infected. RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy kit and quantitated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. To construct a transcript library for sequencing, mRNA was purified with poly-T oligoconjugated magnetic beads. The purified mRNA was fragmented and primed with random hexamers for cDNA synthesis. cDNA fragments were adenylated and then ligated to indexing adapters. The cDNA fragments were purified and enriched by PCR, then sequenced on a BGISEG-500 using single-ended read and 50bp cycles. The total clean reads were 21.9 M, clean bases 1.1 Gb. The clean read ratio was >99.7%, total mapping ratio >96%, and unique mapping ratio 77.3%–79.3%. Sequences are available from the GEO (accession number GSE159450). SOAPnuke version 1.5.2 (https://github.com/BGI-flexlab/SOAPnuke) was used to analyze the RNA-sequence data. Bowtie2 version 2.2.5 and RSEM version 1.2.12 were used to map sequencing read to mm10 genome and quantify reads. DESeq2 version 1.0.0 was applied to calculate the differential expression of genes. The genes with a ≥2 fold difference and false discovery rate ≤ 0.01 were analyzed for canonical functional pathways by the ingenuity pathway analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test, 2-tailed Student t test, or multiple t tests, depending on the data distribution and the number of comparison groups. P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

STING Signaling Restricts CHIKV Infection and Arthritis Pathogenesis

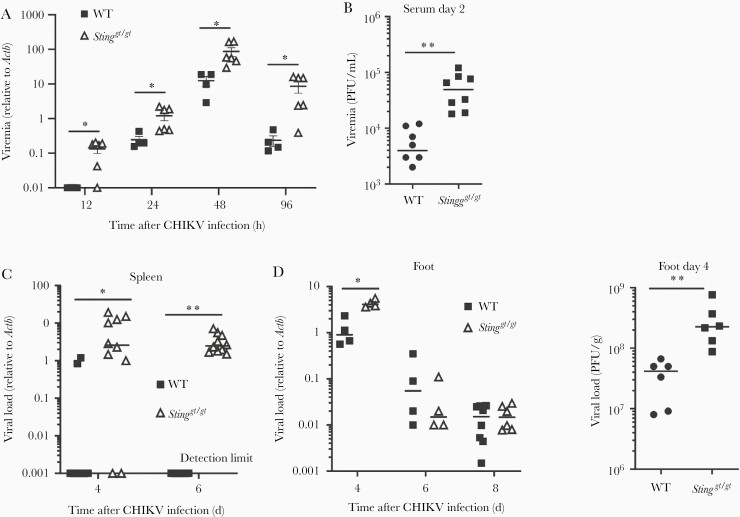

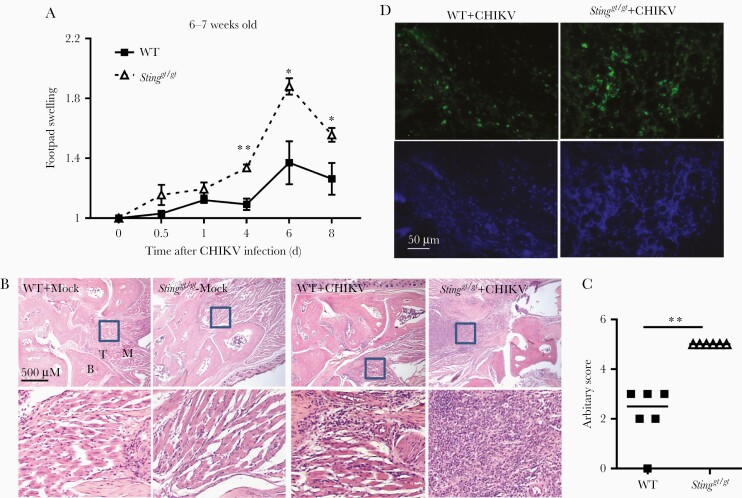

Our studies with West Nile virus and other recent studies conclusively demonstrated that STING is also important for the control of RNA virus infection in mouse models [7, 10–12]. This was also observed with CHIKV infection (Figure 1). When inoculated directly into a mouse footpad, CHIKV elicits brief viremia that lasts approximately 5 days with overt arthritic symptoms, including the first peak of foot swelling characteristic of edema during 2–3 days, followed by a second peak at 6–8 days post infection (dpi) [22] with massive infiltration of immune cells into infected feet [23, 24]. Sting-deficient mice (Stinggt/gt) [25] presented a significant increase in viremia from 12 through 96 hours post infection (hpi) compared to WT mice (Figure 1A and 1B), which accompanied higher viral loads in the spleen of Stinggt/gt than WT mice (Figure 1C). The viral loads in the feet were elevated at 4 dpi in Stinggt/gt compared to WT mice; however, this difference disappeared by 6–8 dpi. (Figure 1D). Moreover, Stinggt/gt mice showed much greater footpad swelling from 4 to 8 dpi compared to WT mice (Figure 2A). Hematoxylin and eosin and immunofluorescence staining for CD45 demonstrated a significant increase of immune cells in the muscle/synovial cavity/tendon of Stinggt/gt compared to WT mice (Figure 2B–2D). Interestingly, although the viral loads in Stinggt/gt joints were the same as WT at 6 and 8 dpi (Figure 1D), the foot and joint disease manifestations were much more severe in Stinggt/gt (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Increased CHIKV infection in Stinggt/gt mice. Age- and sex-matched, C57BL/6 (WT) and STING deficient (Stinggt/gt) mice were infected with CHIKV. A, Quantitative RT-PCR quantification of CHIKV loads in whole-blood cells. B, Viremia of day 2 sera quantified by plaque forming assay (PFU/mL serum). C, Quantitative PCR analysis of CHIKV loads in the spleen. D, Footpads viral load in day 4, 6, and 8 and viral titers in day 4 post infection (PFU/g tissue). Each symbol represents 1 mouse; short horizontal line indicates the median. The data represent 2 independent experiments. *, P < .05; **, P < .01 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test). Abbreviations: CHIKV, chikungunya virus; PFU, plaque-forming unit; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; STING, stimulator of interferon gene; WT, wild type.

Figure 2.

Exacerbated joint inflammation in Stinggt/gt mice. A, Fold changes in the footpad dimensions of infected (at days 0.5, 1, 4, 6, and 8 post infection) over the uninfected (day 0). Bars indicate mean + SEM. B, Representative micrographs of staining H&E from mock- and CHIKV-infected joints at day 8 post infection (× 40). The boxed areas indicate the regions with severe immune cell infiltration and tissue damage (× 200). C, Arbitrary H&E scores for the CHIKV-infected footpads/ankle joints at day 8 post infection using a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 representing the worst disease presentation. Each symbol represents 1 mouse; short horizontal line indicates the median. n = 6/genotype. *, P < .05; **, P < .01 (2-tailed unpaired Student t test). The data represent 2 independent experiments. D, Confocal microscopic images of immunofluorescence staining for a pan-immune cell marker CD45 (× 200). Abbreviations: B, bone; CHIKV, chikungunya virus; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; M, muscle; STING, stimulator of interferon gene; T, tendon; WT, wild type.

STING Signaling Is Dispensable for the IFN-I Response During CHIKV Infection

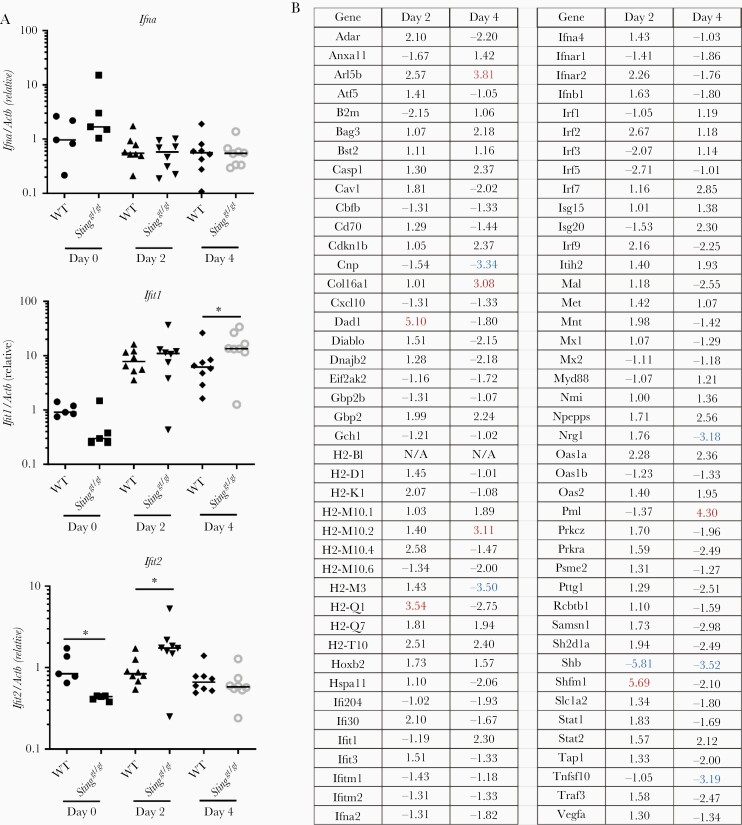

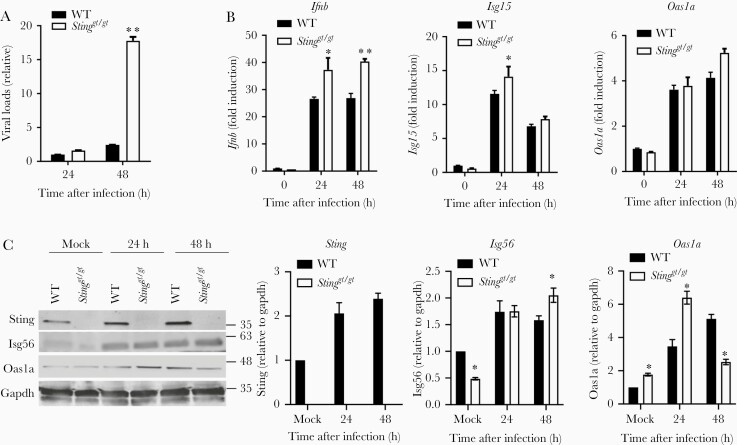

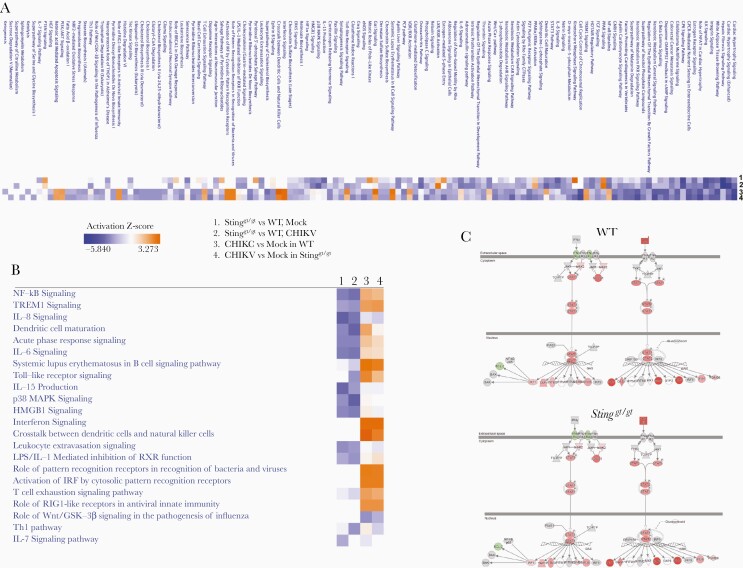

The aforementioned results clearly demonstrate the importance of STING in the control of CHIKV infection at the very early stage of infection and disease pathogenesis in vivo. Next, we evaluated the IFN-I response. The mRNA expression of Ifna by leukocytes was barely induced at the peaks of viremia (days 2–4) in both WT and Stinggt/gt mice, consistent with a dominant role of nonhematopoietic cells in IFN-I production [3]. While Ifit1 and Ifit2 ISGs were both upregulated by CHIKV infection and increased in Stinggt/gt mice on 4 and 2 dpi, respectively (Figure 3A). We further analyzed the expression of 84 genes related to the IFN-I response by PCR array in WT and Stinggt/gt mice. Considering the larger variations among individual mice, we set an arbitrary cutoff of >3 fold. We observed no genes with a >3-fold difference at both time points (Figure 3B). In vitro, the intracellular CHIKV load was increased in bone-marrow–derived Stinggt/gt macrophages compared to WT cells (Figure 4A). The mRNA expression of Ifnb1 and ISGs (Isg15, Isg56, and Oas1a) was slightly higher in Stinggt/gt than WT cells after infection (Figure 4B), as was Isg56 (48 hpi) and Oas1a (24 hpi) protein expressions, while Oas1a was modestly lower in Stinggt/gt (48 hpi) (Figure 4C). Sting protein expression was also upregulated throughout infection (Figure 4C), suggesting that CHIKV-induced IFN-I signaling is largely intact in Stinggt/gt. To unbiasedly examine if the IFN-I response or other immune signaling pathways were deficient in Stinggt/gt cells during CHIKV infection, we performed RNAseq analysis of whole-genome transcripts in bone-marrow–derived macrophages following mock or CHIKV infection. We compared the global gene expression profile between WT and Stinggt/gt without infection (mock) or 12 hours after infection (CHIKV), between mock- and CHIKV-infected WT, and between mock- and CHIKV-infected Stinggt/gt cells. We identified differentially expressed genes (Supplementary Table 1) and the biological pathways that were significantly altered between 2 groups using the differentially expressed genes with a log2-fold change ≤ −1 (downregulated) or ≥1 (upregulated) and Q ≤ .01 (Figure 5). The expression levels of 909 genes in Stinggt/gt were different from those in WT without infection, and 677 were altered after CHIKV infection. Compared to the uninfected mock, 2754 genes in WT cells and 3541 genes in Stinggt/gt were either up- or downregulated after CHIKV infection (Supplementary Table 1). The top pathways that were repressed by CHIKV infection in both WT and Stinggt/gt cells were cardiac hypertrophy signaling, cell cycle control of chromosomal replication, and xenobiotic metabolism signaling (Figure 5A). Compared to WT, hepatitis fibrosis, GP6, and cardiac hypertrophy signaling pathways were attenuated in Stinggt/gt cells without (mock) or with CHIKV infection. Not surprisingly, the primary pathways activated by CHIKV were immune related, including IFN, pathogen pattern recognition receptors, cross-talk between dendritic cells and natural killer cells, and systemic lupus erythematosus. The activation Z scores for these pathways were similar between WT and Stinggt/gt (Figure 5B). A specific examination of the IFN-I signaling pathway revealed that Ifna/b, Ifit1, Ifit3, and G1p2 were upregulated most significantly and similarly between WT and Stinggt/gt (Figure 5C). These results are in agreement with the aforementioned PCR array and qPCR results, suggesting that STING is nonessential for the IFN-I response during CHIKV infection.

Figure 3.

A normal type I IFN response in Stinggt/gt mice during CHIKV infection. A, qPCR quantification of immune gene expression in whole-blood cells. Each symbol represents 1 mouse; short horizontal line indicates the median. The data represent 2 independent experiments. *, P < .05 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test). B, PCR array of differentially expressed type I IFN response-related genes in the white blood cells of WT and Stinggt/gt mice at 2 and 4 days post CHIKV infection (samples pooled from 8 mice, respectively). The results represent fold changes of Stinggt/gt over WT mice. A negative value (highlighted in blue) indicates downregulation; a positive (highlighted in red) denotes upregulation. N/A indicates expression below detection in either Stinggt/gt or WT. The cutoff is arbitrarily set at 3-fold. Abbreviations: CHIKV, chikungunya virus; IFN, interferon; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; STING, stimulator of interferon gene; WT, wild type.

Figure 4.

An intact type I IFN response in Stinggt/gt macrophages during CHIKV infection. qPCR quantification of the (A) cellular viral loads and (B) select immune genes in WT and Stinggt/gt BMDMs infected with CHIKV at a multiplicity of infection of 2 (n = 4 replicates). C, Immunoblots of the indicated interferon stimulated genes in BMDMs. Bars indicate mean + SEM. *, P < .05; **, P < .01 (2-tailed unpaired Student t test). The data shown are representative of 2 independent reproducible experiments. Abbreviations: BMDM, bone-marrow–derived macrophage; CHIKV, chikungunya virus; IFN, interferon; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; STING, stimulator of interferon gene; WT, wild type.

Figure 5.

Analysis of altered canonical functional pathways in Stinggt/gt macrophages. Bone-marrow–derived macrophages from 3 individual WT/Stinggt/gt mice were infected by CHIKV at a multiplicity of infection of 5 for 12 hours or not infected (mock). The whole-genome transcriptome was analyzed by RNAseq. The genes with a ≥2 fold difference and Q ≤ .01 were included for analysis of canonical functional pathways by ingenuity pathway analysis: (1) Stinggt/gt versus WT cells without CHIKV (mock), (2) WT and Stinggt/gt cells CHIKV-infected, (3) CHIKV-infected versus mock-infected WT cells, and (4) CHIKV-infected versus mock-infected Stinggt/gt cells. The ranking of activation (orange) or suppression (blue) of a pathway is indicated by Z-score. A, The top activated/suppressed canonical pathways. B, The immune pathways. C, The type I IFN pathway. The individual genes highlighted in red/green were up- or downregulated in CHIKV-infected compared to uninfected cells. The genes in gray were not significantly different after infection (≥2-fold difference and false discovery rate ≤ 0.01). Genes in white were not present in the dataset. WT and Stinggt/gt are presented separately. The color intensity correlates with expression level: the darker the color, the higher the gene expression. Abbreviations: CHIKV, chikungunya virus; IFN, interferon; STING, stimulator of interferon gene; WT, wild type.

Aberrant Chemokine Expression in the Stinggt/gt Joints During CHIKV Arthritis Progression

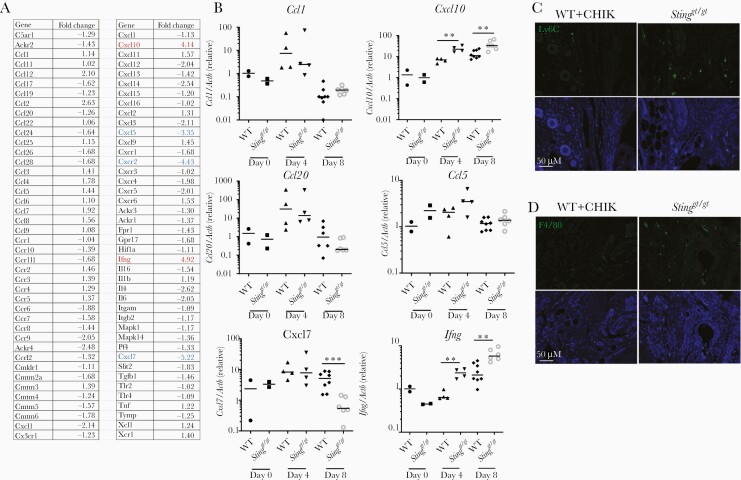

Because immune cell infiltration into joints and muscles is a hallmark of CHIKV arthritis, we examined chemoattractant expression in mouse ankle joints. A chemokine PCR array was performed with joint samples at the peak of disease (8 dpi). Two genes, Ifng and Cxcl10 (also known as IFN-γ inducible gene-IP10, a chemoattractant for T cells, monocytes/macrophages), were upregulated by 4 to 5-fold and 3 genes, Cxcl5, Cxcr2, and Cxcl7 (known to participate in neutrophil recruitment and activation) were downregulated by over 3-fold in Stinggt/gt compared to WT mice (Figure 6A). We next validated the PCR array results and investigated the kinetics of chemokine expression during the course of CHIKV infection. In WT mouse joints, Ifng and Cxcl10 mRNA expression was continuously upregulated by approximately 7 to 10-fold, and further elevated in Stinggt/gt mice at 4–8 dpi (Figure 6B), synchronously with arthritis progression. Cxcl7 expression was equally upregulated in both WT and Stinggt/gt mice at 4 dpi, but rapidly decreased at 8 dpi in Stinggt/gt mice (Figure 6B). Ccl5 (a chemoattractant for T cells, eosinophils, and basophils), Ccl1 (chemoattractant for monocytes), and Ccl20 (strongly chemotactic for lymphocytes) were transiently upregulated at 4 dpi and downregulated at 8 dpi similarly in both WT and Stinggt/gt mice (Figure 6B). In agreement with increased expression of Cxcl10, the numbers of monocytes (Ly6C+) and macrophages (F4/80+) were increased at 8 dpi in Stinggt/gt relative to WT footpads (Figure 6C and 6D). These data demonstrate that IFN-γ and CXCL10 expression kinetics are in line with arthritis progression and suggest a role for IFN-γ and CXCL10 in disease pathogenesis.

Figure 6.

Differential chemokine expression in the joints of Stinggt/gt following CHIKV infection. A, PCR array of differentially expressed chemokine genes in the ankle joints of WT and Stinggt/gt mice at day 8 post infection (samples pooled from 8 mice per strain). The results represent fold changes of Stinggt/gt over WT mice. A negative value (highlighted in blue) indicates downregulation; a positive (highlighted in red) denotes upregulation. The cutoff is arbitrarily set at 3-fold. B, qPCR validation of PCR array results. Each symbol represents 1 mouse; short horizontal line indicates the median. The data represent 2 independent experiments. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test). C and D, Representative microscopic images of immunofluorescence staining for Ly6C and F4/80 in the footpads at day 8 post CHIKV infection (objective lens × 20). Abbreviations: CHIKV, chikungunya virus; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; STING, stimulator of interferon gene; WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

The function and regulation of STING signaling has been well established in the context of cytosolic DNA stimulation of either self or foreign origin [26]. However, its anti-RNA virus mechanisms remain largely elusive [26]. The IFN-I expression in Sting−/− cells and/or mice was mildly decreased during influenza virus [27], vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), and Sendai virus (SeV), but not encephalomyocarditis virus [7, 8, 25]. We, however, observed no significant differences in the IFN-I response elicited by CHIKV in Stinggt/gt macrophages and mice by multiple approaches (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5). One possible explanation for these discrepancies is that CHIKV activates both RIG-I and MDA5 for a full IFN-I response [28, 29], while VSV, SeV, and influenza viruses rely predominantly on RIG-I [30, 31], which may promote cross-talk with STING to induce IFN-I [8]. Of note, several ISGs, Ifit1/Ifit2, were slightly higher in Stinggt/g mice. This may be a result of increased viremia that activates STING-independent pathways such as RIG-I, MDA5, and Toll-like receptors (TLR) to produce more IFN-I and ISGs. Alternatively, ISG transcription can be induced directly by transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1), IRF2, and IRF3 [32], which could be more active due to elevated viremia in Stinggt/gt than WT mice. Altogether, our results suggest that STING could initiate IFN-I–independent antiviral actions. Indeed, STING could activate STAT6 to induce a specific set of chemokines to RNA virus infection [12] and inhibit viral protein translation [18]. Additionally, STING could activate autophagy [33] to limit CHIKV infection in mice [34]. Our RNAseq analyses of whole-genome transcripts in CHIKV-infected macrophages revealed 2 upregulated signaling pathways, peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) and liver X receptor (LXR)/retinoid X receptor (RXR), and a number of downregulated genes in Stinggt/gt (Figure 5). Although the role of top downregulated genes, hepatitis fibrosis, GP6, and cardiac hypertrophy signaling pathways, in CHIKV infection is not clear, many others are immune related, such as NF-κB, dendritic cell activation, p38 MAPK, interleukin-6 (IL-6), etc. that may contribute to antiviral immune responses during CHIKV infection. Of note, PPAR and LXR are nuclear receptors that suppress the activity of transcription factors like NF-κB, STAT, and AP-1 [35], potentially leading to weakened antiviral immune responses.

Intriguingly, exacerbated pathology progressed in Stinggt/gt mouse feet even when viral loads were reduced to a similarly low level between WT and Stinggt/gt mice at 6 and 8 dpi, respectively (Figure 1D and Figure 2). These results are in agreement with previous observations showing that CHIKV arthritis severity is not always positively correlated with viral loads [36], but is rather a primary consequence of dysregulated inflammatory responses. Indeed, immune cell infiltration is a hallmark of acute CHIKV infection, primarily including macrophages and monocytes, but also neutrophils, dendritic cells, NK cells, and lymphocytes [37]. Of note, although CD4+ T cells constitute only a small fraction of immune infiltrates in CHIKV-infected joints [38], they contribute significantly to arthritis pathogenesis [36]. In agreement with this, expression of CXCL10, a chemoattractant primarily for monocytes, macrophages, and T cells, was highly upregulated synchronously with arthritis progression, along with further elevation of monocytes and macrophages in Stinggt/gt joints (Figure 6). In particular, the severity of CHIKV arthritis in humans is associated with a high level of serum CXCL10 and CXCL9 [39, 40]. Interestingly, we also noted elevated Ifng expression in Stinggt/gt compared to WT joints, and its kinetics was coincident with disease progression (Figure 6B). This is in agreement with previous studies showing an association between elevated IFN-γ expression and CHIKV arthritis [40, 41]. IFN-γ could be predominantly expressed by infiltrating NK during the early stage of CHIKV infection (Figure 6B, day 4), and by CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ T cells once antigen-specific immunity develops (Figure 6B, day 8) [37, 42]. Thus, elevated Ifng mRNA expression in Stinggt/gt joints suggests increased infiltration of these cells. In contrast, CXCL10 can be produced by many infiltrating immune cells including monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils, etc. In particular, synovial macrophages could be a source of CHIKV persistence and CXCL10 [23, 43]. Moreover, CXCL10 is expressed by many tissue cells where synovial fibroblast hyperplasia is a signature of CHIKV arthritis [23]. These cells are also a primary target of CHIKV [44], and may express abundant CXCL10 through pathogen pattern recognition receptors and IFN-γ signaling pathways [45]. Skeletal muscle cells are a primary target of CHIKV and may also contribute to CXCL10 production [46]. Thus, our data suggest that STING signaling may not only limit viral replication at the early stage, but also keep aberrant inflammatory responses in check to avoid immunopathology at the late stage of infection. Indeed, STING signaling can induce expression of negative regulators of innate immune signaling, such as suppressor of cytokine signaling, to control TLR-mediated hyperinflammatory immune responses in a lupus mouse model [47]. In particular, TLR7 (a viral RNA sensor) signaling could contribute to immunopathology as plasmacytoid dendritic cells express a very high level of TLR7 and were the most rapidly and highly expanded immune infiltrate in CHIKV-infected mouse footpads [48].

Neutrophils infiltrate the joints rapidly after CHIKV infection and seem to contribute to CHIKV arthritis pathogenesis [49]. Surprisingly, 3 genes related to neutrophil recruitment and activation (Cxcr2 and its ligands Cxcl5 and Cxcl7) [50] were down-regulated in Stinggt/gt joints at 8 dpi (Figure 6B), which could result from elevated expression of IFN-γ, a suppressor of CXCL5 and CXCL7 [50]. These data suggest that increased arthritis severity in Stinggt/gt mice is a result of accumulation of immune cells other than neutrophils. An abnormally high level of IFN-γ/CXCL10 could drive a robust Th1 response that exacerbates arthritis [49] in Stinggt/gt joints. In the future, it would therefore be interesting to examine the kinetics of each immune population in the joints during the course of CHIKV infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. T. G. designed and performed the majority of the experimental procedures and data analyses. T. L., A. G. H., and D. Y. contributed to experiments and/or provided technical support. A. T. V. and E. F. helped with data interpretations and writing. P. W. conceived and oversaw the study. T. G. and P. W. wrote the paper and all the authors reviewed and/or modified the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01AI132526 to P. W.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Kendrick K, Stanek D, Blackmore C; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Notes from the field: Transmission of chikungunya virus in the continental United States–Florida, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:1137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weaver SC, Lecuit M. Chikungunya virus and the global spread of a mosquito-borne disease. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schilte C, Couderc T, Chretien F, et al. Type I IFN controls chikungunya virus via its action on nonhematopoietic cells. J Exp Med 2010; 207:429–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akahata W, Yang ZY, Andersen H, et al. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med 2010; 16:334–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poo YS, Rudd PA, Gardner J, et al. Multiple immune factors are involved in controlling acute and chronic chikungunya virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang AY, Martins KAO, Encinales L, et al. Chikungunya arthritis mechanisms in the Americas: a cross-sectional analysis of chikungunya arthritis patients twenty-two months after infection demonstrating no detectable viral persistence in synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70:585–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature 2008; 455:674–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature 2009; 461:788–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 2013; 339:786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nazmi A, Mukhopadhyay R, Dutta K, Basu A. STING mediates neuronal innate immune response following Japanese encephalitis virus infection. Sci Rep 2012; 2:347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. You F, Wang P, Yang L, et al. ELF4 is critical for induction of type I interferon and the host antiviral response. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:1237–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen H, Sun H, You F, et al. Activation of STAT6 by STING is critical for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 2011; 147:436–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holm CK, Jensen SB, Jakobsen MR, et al. Virus-cell fusion as a trigger of innate immunity dependent on the adaptor STING. Nat Immunol 2012; 13:737–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Y, Goulet ML, Sze A, et al. RIG-I-mediated STING upregulation restricts herpes simplex virus 1 infection. J Virol 2016; 90:9406–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aguirre S, Luthra P, Sanchez-Aparicio MT, et al. Dengue virus NS2B protein targets cGAS for degradation and prevents mitochondrial DNA sensing during infection. Nat Microbiol 2017; 2:17037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoggins JW, MacDuff DA, Imanaka N, et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 2014; 505:691–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGuckin Wuertz K, Treuting PM, Hemann EA, et al. STING is required for host defense against neuropathological West Nile virus infection. PLoS Pathog 2019; 15:e1007899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Franz KM, Neidermyer WJ, Tan YJ, Whelan SPJ, Kagan JC. STING-dependent translation inhibition restricts RNA virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:E2058–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang P. Exploration of West Nile virus infection in mouse models. Methods Mol Biol 2016; 1435:71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pal U, Wang P, Bao F, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi basic membrane proteins A and B participate in the genesis of Lyme arthritis. J Exp Med 2008; 205:133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang L, Wang L, Ketkar H, et al. UBXN3B positively regulates STING-mediated antiviral immune responses. Nat Commun 2018; 9:2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fox JM, Diamond MS. Immune-Mediated protection and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. J Immunol 2016; 197:4210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoarau JJ, Jaffar Bandjee MC, Krejbich Trotot P, et al. Persistent chronic inflammation and infection by chikungunya arthritogenic alphavirus in spite of a robust host immune response. J Immunol 2010; 184:5914–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gasque P, Couderc T, Lecuit M, Roques P, Ng LF. Chikungunya virus pathogenesis and immunity. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2015; 15:241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sauer JD, Sotelo-Troha K, von Moltke J, et al. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect Immun 2011; 79:688–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen Q, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:1142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holm CK, Rahbek SH, Gad HH, et al. Influenza A virus targets a cGAS-independent STING pathway that controls enveloped RNA viruses. Nat Commun 2016; 7:10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goubau D, Deddouche S, Reis e Sousa C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity 2013; 38:855–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akhrymuk I, Frolov I, Frolova EI. Both RIG-I and MDA5 detect alphavirus replication in concentration-dependent mode. Virology 2016; 487:230–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 2006; 441:101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Loo YM, Fornek J, Crochet N, et al. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J Virol 2008; 82:335–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang W, Xu L, Su J, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Transcriptional regulation of antiviral interferon-stimulated genes. Trends Microbiol 2017; 25:573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gui X, Yang H, Li T, et al. Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature 2019; 567:262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang L, Geng T, Yang G, et al. Macrophage scavenger receptor 1 controls chikungunya virus infection through autophagy in mice. Commun Biol 2020; 3:556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glass CK, Ogawa S. Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6:44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Teo TH, Lum FM, Claser C, et al. A pathogenic role for CD4+ T cells during chikungunya virus infection in mice. J Immunol 2013; 190:259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Silva LA, Dermody TS. Chikungunya virus: epidemiology, replication, disease mechanisms, and prospective intervention strategies. J Clin Invest 2017; 127:737–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morrison TE, Oko L, Montgomery SA, et al. A mouse model of chikungunya virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease: evidence of arthritis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and persistence. Am J Pathol 2011; 178:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kelvin AA, Banner D, Silvi G, et al. Inflammatory cytokine expression is associated with chikungunya virus resolution and symptom severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011; 5:e1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Long KM, Ferris MT, Whitmore AC, et al. γδ T cells play a protective role in chikungunya virus-induced disease. J Virol 2016; 90:433–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nakaya HI, Gardner J, Poo YS, Major L, Pulendran B, Suhrbier A. Gene profiling of chikungunya virus arthritis in a mouse model reveals significant overlap with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:3553–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol 2007; 96:41–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Labadie K, Larcher T, Joubert C, et al. Chikungunya disease in nonhuman primates involves long-term viral persistence in macrophages. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:894–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwartz O, Albert ML. Biology and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010; 8:491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kato M. New insights into IFN-γ in rheumatoid arthritis: role in the era of JAK inhibitors. Immunol Med 2020; 43:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lentscher AJ, McCarthy MK, May NA, et al. Chikungunya virus replication in skeletal muscle cells is required for disease development. J Clin Invest 2020; 130:1466–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sharma S, Campbell AM, Chan J, et al. Suppression of systemic autoimmunity by the innate immune adaptor STING. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:E710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gardner J, Anraku I, Le TT, et al. Chikungunya virus arthritis in adult wild-type mice. J Virol 2010; 84:8021–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Poo YS, Nakaya H, Gardner J, et al. CCR2 deficiency promotes exacerbated chronic erosive neutrophil-dominated chikungunya virus arthritis. J Virol 2014; 88:6862–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Persson T, Monsef N, Andersson P, et al. Expression of the neutrophil-activating CXC chemokine ENA-78/CXCL5 by human eosinophils. Clin Exp Allergy 2003; 33:531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.