Abstract

Objective: To determine the positive effect of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) combined with progesterone on endometrial thickness and pregnancy outcomes of patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) or early-stage endometrial cancer (EEC). Methods: Patients with AEH or EEC admitted to our hospital were enrolled, and assigned to a control group (con group) and a combination group (com group). Patients in the con group were treated with LNG-IUS, while those in the com group were treated with LNG-IUS combined with progesterone. After treatment, the two groups were compared in efficacy, menstrual blood volume (pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC) score), and changes in endometrial thickness. In addition, the incidence of adverse drug reactions and pregnancy outcomes of the patients were analyzed. Results: Before treatment, there was no significant difference in PBAC score and endometrial thickness between patients with AEH or EEC in the con group and those in the com group, but after 3 months and 6 months of treatment, the com group got a better PBAC score and better changes of endometrial thickness than the con group, and the incidence of adverse drug reactions in the com group was also significantly lower than that in the con group. In addition, the follow-up results of pregnancy outcomes of patients showed that the fertility rate and total effective rate of the com group were both significantly higher than those of the con group (both P<0.05). Conclusion: LNG-IUS combined with progesterone is more effective in treating patients with AEH or EEC. It can effectively improve the endometrial thickness of patients and fertility rate of those with fertility requirements after treatment.

Keywords: Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, progesterone, atypical endometrial hyperplasia, early-stage endometrial cancer, endometrial thickness, pregnancy outcome

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) and atypical hyperplasia are common clinical gynecological diseases [1]. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) is the main manifestation of precancerous lesions of EC. A large number of studies have confirmed that AEH often coexists with EC [2]. Therefore, endometrial hyperplasia that is not treated promptly and effectively can easily deteriorate into cancer, and eventually develops into endometrial adenocarcinoma. EC is linked to genetic factors [3] and physical factors such as long-term estrogen stimulation [4], obesity [5], hypertension [6], diabetes mellitus [7], sterility, and infertility [8]. In the very early stage, the disease is usually found only by chance during general screening or examination for other reasons due to the lack of obvious symptoms in this stage. In gynecological examination, patients with early stage EC show no obvious abnormality, because their uterus is normal in size and activity, and both fallopian tubes and ovaries are soft, without lump. Only when the disease gradually develops will the uterus be larger and slightly soft [9]. In addition, EC and AEH have high incidences among postmenopausal women. Studies have shown that approximately 5% of patients with this kind of disease are under 40 years old [10], and they are in a childbearing age, but their reproductive health and fertility are seriously threatened by the disease. At present, the first choice for clinical treatment of early-stage endometrial cancer (EEC) is surgical resection of uterine adnexa [11], and patients with advanced EC are generally treated with drugs. Although the effect of the surgical resection is ideal, it will cost the permanent lose of fertility, which is usually unacceptable to women of childbearing age. Therefore, oral progesterone is taken as the main treatment for AEH and EC. In clinical practice, it is required to choose reasonable treatment methods for patients according to their specific conditions to delay the development of the disease and buy time for further treatment.

Oral progesterone is the first choice of conservative treatment at this point, but it is prone to bring about adverse reactions such as nausea and vomiting, weight gain, and liver function damage after being taken at a large dose orally, and it causes poor compliance of patients [12]. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), also known as mirena, means that the levonorgestrel intrauterine sustained-release system is placed in the uterus, which can enhance the concentration of levonorgestrel in local tissues in the uterus to be much higher than the blood concentration, thereby significantly reducing the systemic adverse reactions of progesterone [13]. It has been gradually adopted to treat stage I EC. This study mainly compared the efficacy and safety of LNG-IUS alone and LNG-IUS combined with progesterone in the treatment of patients with AEH or EEC.

Materials and methods

Research objects

A total of 47 patients with EEC and 56 patients with AEH admitted to Huaian Maternal and Child Health Hospital from January 2018 to December 2019 were enrolled, and assigned to a control group (con group) and a combination group (com group). Their average age was 30.12±6.76 years, and there were 25 patients with EEC and 20 patients with AEH in the con group, and 31 patients with EEC and 27 patients with AEH in the com group. The inclusion criteria of the study: Patients under 40 years old; patients who required fertility preservation; patients diagnosed as endometrioid adenocarcinoma or AEH according to pathological diagnosis; patients whose progesterone receptor was positive in immunohistochemical staining; patients with normal serum CA125; patients without myometrial infiltration, uterine involvement, and extrauterine metastasis; patients not allergic to related drugs, and those with good compliance. The exclusion criteria of the study: Patients with comorbid tumor in other parts; patients with distant metastasis, and those without fertility preservation requirement. There was no significant difference in general data between the two groups (P>0.05), so the two groups were comparable. All patients signed informed consent forms, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huaian Maternal and Child Health Hospital.

Methods

Patients in the com group were treated with both LNG-IUS and oral progesterone, while those in the con group were treated with LNG-IUS alone. The LNG-IUS was placed in the uterus of each patient after the patient signed consent form under the premise of fully understanding of the study. In addition, before the placement, a doctor was asked to fully understand the patient, inform the patient of related information, and then carry out a series of examinations to the patient, including hysteroscopy, transvaginal ultrasonography, colposcopy, TCT, routine gynecological examination, and basic general check-up. At 4-5 days after diagnostic uterine curettage (generally within 1 week after a menstrual cycle), the LNG-IUS was placed in the uterus of the patient. On the 5th day after menstruation, the patient was asked to orally take progesterone (medroxyprogesterone acetate with a specification of 2 mg) at 10 mg/d for 22 consecutive days, and the treatment was continued for 6 menstrual cycles. After treatment, the difference of efficacy between the two groups was evaluated.

Outcome measures

The efficacy on each patient was evaluated, and the pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC) was adopted to evaluate the improvement of menstruation after treatment. In addition, the changes in endometrial thickness of each patient were analyzed by the transvaginal ultrasonography, and adverse reactions in patients after treatment were recorded. Moreover, the patients were followed up to understand their pregnancy outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Data in this study were statistically analyzed using SPSS 22.0. Measurement data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and compared between groups using the t test. Enumeration data were presented by n (%), and analyzed by the chi-square test. P<0.05 was adopted to suggest a significant difference. Data in this study were visualized into figures using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Results

Comparison of general data

There was no significant difference between patients with EEC or AEH in the con group and those in the com group in general clinical data, so the two groups were comparable (all P<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

General data

| Early-stage endometrial carcinoma | χ2/t | P-value | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia | χ2/t | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| The control group (n=25) | The combination group (n=31) | The control group (n=20) | The combination group (n=27) | |||||

| Age | 0.0096 | 0.9217 | 0.0207 | 0.8857 | ||||

| <32 | 15 (60.0) | 19 (61.3) | 13 (65.0) | 17 (62.9) | ||||

| ≥32 | 10 (40.0) | 12 (38.7) | 7 (35.0) | 10 (27.5) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.0577 | 0.8102 | 0.1231 | 0.7257 | ||||

| <30 | 17 (68.0) | 22 (70.9) | 15 (75.0) | 19 (70.4) | ||||

| ≥30 | 8 (32.0) | 9 (29.1) | 5 (25.0) | 8 (29.6) | ||||

| Abnormal menstruation | 0.0075 | 0.9307 | 0.0026 | 0.9592 | ||||

| Yes | 14 (56.0) | 17 (54.8) | 12 (60.0) | 16 (59.3) | ||||

| No | 11 (44.0) | 14 (35.2) | 8 (40.0) | 11 (40.7) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 9 (36.0) | 11 (35.5) | 0.0016 | 0.9680 | 7 (35.0) | 9 (33.3) | 0.0142 | 0.9051 |

| Hypertension | 7 (28.0) | 10 (32.3) | 0.1187 | 0.7305 | 6 (30.0) | 7 (25.9) | 0.0953 | 0.7575 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (24.0) | 8 (25.8) | 0.0241 | 0.8767 | 5 (25.0) | 6 (22.2) | 0.0495 | 0.8240 |

| Family history of cancer | 2 (8.0) | 5 (16.1) | 0.8361 | 0.3605 | 1 (5.0) | 3 (11.1) | 0.5511 | 0.4579 |

| Insulin resistance | 12 (48.0) | 16 (51.6) | 0.0723 | 0.7881 | 10 (50.0) | 13 (48.1) | 0.0158 | 0.9001 |

Comparison of efficacy in patients after treatment

The total effective rate of patients with EEC or AEH in the com group was significantly higher than that of patients with the same disease in the con group (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of efficacy in patients after treatment

| Efficacy | Early-stage endometrial carcinoma | ||||

|

| |||||

| Complete remission (CR) | Partial remission (PR) | Stable disease (SD) | Progressive disease (PD) | Total effective rate | |

|

| |||||

| The control group (n=25) | 15 (60.0) | 3 (12.0) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (8.0) | 18 (72.0) |

| The combination group (n=31) | 27 (87.1) | 2 (6.4) | 2 (6.4) | 0 | 29 (93.5) |

| χ2/t | 4.7641 | ||||

| P-value | 0.0291 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Efficacy | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia | ||||

|

| |||||

| Complete remission (CR) | Partial remission (PR) | Stable disease (SD) | Progressive disease (PD) | Total effective rate | |

|

| |||||

| The control group (n=20) | 11 (55.0) | 3 (15.0) | 6 (20.0) | 1 (5.0) | 14 (70.0) |

| The combination group (n=27) | 23 (85.2) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | 0 | 25 (92.6) |

| χ2/t | 4.1521 | ||||

| P-value | 0.0416 | ||||

PBAC score about menstrual blood volume of patients

The PBAC scores of patients with EEC or AEH before treatment, after 3 months of treatment, and 6 months of treatment were compared. It was turned out that before treatment, there was no significant difference in PBAC score between the com group and the con group (P>0.05), while after treatment, the PBAC scores of both groups decreased, and the PBAC score of the com group was significantly lower than that of the con group (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

PBAC score about menstrual blood volume of patients

| PBAC | Early-stage endometrial carcinoma | ||

|

| |||

| Before treatment | After 3 months of treatment | After 6 months of treatment | |

|

| |||

| The control group (n=25) | 153.36±18.52 | 66.25±8.36 | 38.61±6.25 |

| The combination group (n=31) | 157.64±17.38 | 53.35±7.26 | 30.23±6.02 |

| χ2/t | 0.8897 | 5.2199 | 5.0912 |

| P-value | 0.3776 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||

| PBAC | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia | ||

|

| |||

| Before treatment | After 3 months of treatment | After 6 months of treatment | |

|

| |||

| The control group (n=20) | 128.64±15.23 | 54.6±9.26 | 29.62±6.57 |

| The combination group (n=27) | 129.56±15.33 | 40.25±8.26 | 20.36±6.23 |

| χ2/t | 0.2039 | 5.5933 | 4.9229 |

| P-value | 0.8393 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

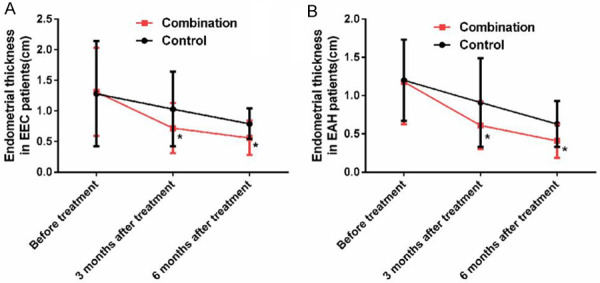

Analysis on amelioration of endometrial thickness

Before treatment, there was no significant difference in endometrial thickness between patients with EEC and patients with AEH (P>0.05), while after treatment, the endometrial thickness of all patients became thinner, and the thickness of the com group was significantly thinner than that of the con group (P<0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes of endometrial thickness in patients. A: Endometrial thickness in EEC patient; B: Endometrial thickness in EAH patient; *indicates P<0.05 vs. the control group.

Incidence of adverse drug reactions

Compared with the con group, the incidence of adverse drug reactions in the com group was significantly lower (P<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of adverse drug reactions in patients

| Weight gain | Menstrual changes | Mammary swelling pain | Nausea and vomiting | Dizziness and hypodynamia | The total incidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early-stage endometrial carcinoma | The control group (n=25) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 9 (36.0) |

| The combination group (n=31) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.9) | |

| χ2/t | 8.0953 | ||||||

| P | 0.0441 | ||||||

| Atypical endometrial hyperplasia | The control group (n=20) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| The combination group (n=27) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| χ2/t | 3.9151 | ||||||

| P | 0.0479 | ||||||

Pregnancy outcomes of patients requiring fertility preservation

Among patients with complete remission, the patients in the con group all asked for fertility preservation, and in the com group, there were unmarried and divorced patients, so patients who asked for fertility preservation were fewer. In terms of patients with EEC who required fertility preservation, the fertility rate of the com group (55%) was significantly higher than that of the con group (20%). In terms of patients with AEH who required fertility preservation, the fertility rate of the com group (62%) was also significantly higher than that of the con group (18.1%) (P<0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of pregnancy outcomes of patients

| Number of patients requiring fertility preservation | Number of patients with pregnancy | Pregnancy rate | Number of pregnancies | Successful delivery | Fertility rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early-stage endometrial carcinoma | The control group (n=25) | 15 | 7 | 7/15 | 12 | 3 | 1/5 |

| The combination group (n=31) | 20 | 13 | 13/20 | 19 | 11 | 11/20 | |

| χ2/t | 4.3751 | ||||||

| P-value | 0.0365 | ||||||

| Atypical endometrial hyperplasia | The control group (n=20) | 11 | 5 | 5/11 | 9 | 2 | 2/11 |

| The combination group (n=27) | 16 | 12 | 3/4 | 13 | 10 | 5/8 | |

| χ2/t | 5.1851 | ||||||

| P-value | 0.0228 | ||||||

Discussion

Modern medicine believes that the occurrence of endometrial hyperplasia is mainly related to the constant stimulation of estrogen on endometrium and the lack of progesterone in the body for antagonism [14], which leads to abnormal menstruation of patients. Endometrial hyperplasia is mainly manifested as an ovulatory dysfunction, and it will induce cancer in severe cases, namely EC. Oral progesterone can resist the induction of estrogen on the proliferation of endometrium, so it is effective in the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia to a certain extent. However, during treatment, progesterone should be used in a large dose and for a long term, which may bring about a wide range of adverse reactions to the whole body, but if the treatment of progesterone does not continue, patients will face a higher rate of recurrence [15]. One study has shown that after treatment with medroxyprogesterone, lynestrenol, or norethisterone for 3 months, the endometrial reversal rates of patients are all low, and the patients still require further treatment [16]. LNG-IUS is a T-shaped intrauterine device placed in the uterine cavity. The T-shaped plastic frame is a frame made of polyethylene, with a hormone repository around the trunk. It contains a total of 52 mg levonorgestrel and can release 20 μg levonorgestrel into the uterine cavity every day, and the released drug directly acts on the endometrium and myometrium. Progesterone with a local high concentration in the uterus can better inhibit the proliferation of endometrium, and after treatment with it, endometrium will change to be in secretory phase or atrophy and the interstitial cells will become decidualized [17,18].

In this study, we compared the efficacy of LNG-IUS alone and LNG-IUS combined with progesterone in the treatment of patients with AEH or EEC. After 3 months and 6 months of treatment, the com group got better PBAC score and better changes of endometrial thickness than the con group, and the incidence of adverse drug reactions in the com group was also significantly lower than that in the con group. It has been reported that LNG-IUS has good curative effect on atypical complex hyperplasia or EC and contributes to good fertility outcomes [19]. The follow-up results of pregnancy outcomes revealed that the fertility rate of the com group was significantly higher than that of the con group, and the total effective rate of the com group was significantly higher than that of the con group. As an intrauterine system, LNG-IUS is a white tubular drug with antiestrogenic activity and with an opaque film on the outer layer [20]. One previous study has found that gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist combined with LNG-IUS can be used as an alternative therapy to retain fertility in patients with EC or AEH [21].

The placement of the system into the uterus will cause local accumulation of high-concentration levonorgestrel, which directly and accurately acts on endometrial stroma and endometrial gland to exert the antagonistic effect on endometrial hyperplasia, promotes the atrophy of endometrium, increases the viscosity of cervical mucus, prevents sperm from entering the cervical canal to prevent fertilization, converts the endometrium from proliferative type to secretory type, and reduces and shortens menstruation [22,23]. However, if it is used alone, it needs a long course of treatment, and older patients with fertility requirement may have to face a delay in giving birth. Progesterone belongs to estrogen, mainly secreted by luteohormone [24], which is effective in preventing fertilization, increasing patients’ body temperature, promoting blood circulation, enhancing endometrial hyperplasia, preventing maternal abortion, and ensuring normal menstrual cycle [25]. Estrogen can maintain acidic environment for vagina, enhance antibacterial ability of vagina, coordinate menstrual cycle, ensure normal menstrual flow, increase extracellular fluid, and promote water and sodium conservation [26]. However, progesterone needs a long course of treatment and has enormous side effects, which will increase the burden of the liver and kidney and increase the incidence of other complications [27]. During combination use of LNG-IUS and progesterone, LNG-IUS will not increase blood concentration and has little side effect, and progesterone can shorten the use of drugs and reduce systemic adverse reactions. Such a complementary effect can improve the treatment compliance of patients and shorten the course of treatment for patients who require fertility.

To sum up, LNG-IUS combined with progesterone can improve the efficacy on patients with AEH or EEC, improve their menstrual status and endometrial thickness, and shorten the treatment course required by one single drug on the basis of reducing adverse reactions, so it is worthy of clinical application.

Acknowledgements

Jiangsu Province Maternal and Child Health Research Project. Project name: A randomized controlled clinical study of levonorgestrel intrauterine system combined with progesterone in the treatment of endometrial atypical hyperplasia and early endometrial carcinoma (F201839).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Lax SF. Pathology of endometrial carcinoma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;943:75–96. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-43139-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pal N, Broaddus RR, Urbauer DL, Balakrishnan N, Milbourne A, Schmeler KM, Meyer LA, Soliman PT, Lu KH, Ramirez PT, Ramondetta L, Bodurka DC, Westin SN. Treatment of low-risk endometrial cancer and complex atypical hyperplasia with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:109–116. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson WJ, Hoivik EA, Halle MK, Taylor-Weiner A, Cherniack AD, Berg A, Holst F, Zack TI, Werner HM, Staby KM, Rosenberg M, Stefansson IM, Kusonmano K, Chevalier A, Mauland KK, Trovik J, Krakstad C, Giannakis M, Hodis E, Woie K, Bjorge L, Vintermyr OK, Wala JA, Lawrence MS, Getz G, Carter SL, Beroukhim R, Salvesen HB. The genomic landscape and evolution of endometrial carcinoma progression and abdominopelvic metastasis. Nat Genet. 2016;48:848–855. doi: 10.1038/ng.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanderson PA, Critchley HO, Williams AR, Arends MJ, Saunders PT. New concepts for an old problem: the diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:232–254. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsuhashi A, Uehara T, Hanawa S, Shozu M. Prospective evaluation of abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin resistance in patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1495–1501. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3554-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Azevedo JM, de Azevedo LM, Freitas F, Wender MC. Endometrial polyps: when to resect? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:639–643. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corzo C, Barrientos Santillan N, Westin SN, Ramirez PT. Updates on conservative management of endometrial cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li M, Song JL, Zhao Y, Wu SL, Liu HB, Tang R, Yan L. Fertility outcomes in infertile women with complex hyperplasia or complex atypical hyperplasia who received progestin therapy and in vitro fertilization. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2017;18:1022–1025. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Tian JW, Xu Y, Cheng W. Role of transvaginal contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the early diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:416–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang B, Xu Y, Zhu Q, Xie L, Shan W, Ning C, Xie B, Shi Y, Luo X, Zhang H, Chen X. Treatment efficiency of comprehensive hysteroscopic evaluation and lesion resection combined with progestin therapy in young women with endometrial atypical hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennich G, Rudnicki M, Lassen PD. Laparoscopic surgery for early endometrial cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:894–900. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim DH, Seong SJ, Kim MK, Bae HS, Kim M, Yun BS, Jung YW, Shim JY. Dilatation and curettage is more accurate than endometrial aspiration biopsy in early-stage endometrial cancer patients treated with high dose oral progestin and levonorgestrel intrauterine system. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28:e1. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandi G, Farulla A, Sileo FG, Facchinetti F. Levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine systems as female contraceptives. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:677–686. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1462337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socolov D, Socolov R, Lupascu IA, Rugina V, Gabia O, Garauleanu DM, Carauleanu A. Immunohistochemistry in endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial adenocarcinoma. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2016;120:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamagami W, Susumu N, Makabe T, Sakai K, Nomura H, Kataoka F, Hirasawa A, Banno K, Aoki D. Is repeated high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) therapy permissible for patients with early stage endometrial cancer or atypical endometrial hyperplasia who desire preserving fertility? J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29:e21. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozdegirmenci O, Kayikcioglu F, Bozkurt U, Akgul MA, Haberal A. Comparison of the efficacy of three progestins in the treatment of simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;72:10–14. doi: 10.1159/000321390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wrona W, Stepniak A, Czuczwar P. The role of levonorgestrel intrauterine systems in the treatment of symptomatic fibroids. Prz Menopauzalny. 2017;16:129–132. doi: 10.5114/pm.2017.72758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yun BH, Jeon YE, Seo SK, Park JH, Yoon SO, Cho S, Choi YS, Lee BS. Effects of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on the expression of steroid receptor coregulators in adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:1539–1548. doi: 10.1177/1933719115589411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Martinelli F, Dondi G, Bogani G, Chiappa V, Evangelista MT, Liberale V, Ditto A, Ferrero S, Raspagliesi F. Efficacy and fertility outcomes of levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system treatment for patients with atypical complex hyperplasia or endometrial cancer: a retrospective study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30:e57. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson AL. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS 12) for prevention of pregnancy for up to five years. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10:833–842. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1341308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou H, Cao D, Yang J, Shen K, Lang J. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist combined with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or letrozole for fertility-preserving treatment of endometrial carcinoma and complex atypical hyperplasia in young women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:1178–1182. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patseadou M, Michala L. Usage of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in adolescence: what is the evidence so far? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:529–541. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moraes LG, Marchi NM, Pitoli AC, Hidalgo MM, Silveira C, Modesto W, Bahamondes L. Assessment of the quality of cervical mucus among users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system at different times of use. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:318–322. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2016.1193139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickar JH. Progesterone. Climacteric. 2018;21:305. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2018.1462910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Renzo GC, Giardina I, Clerici G, Brillo E, Gerli S. Progesterone in normal and pathological pregnancy. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2016;27:35–48. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2016-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stachenfeld NS, Taylor HS. Effects of estrogen and progesterone administration on extracellular fluid. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;96:1011–1018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01032.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang YX, Liu L, Jin ZY, Liang XH, Fu YS, Gu XW, Yang ZM. The high concentration of progesterone is harmful for endometrial receptivity and decidualization. Sci Rep. 2018;8:712. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18643-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]