Abstract

Objective: The present study aims to investigate the influence of humanized care on self-efficacy, sleep quality (SQ) and quality of life (QOL) of patients in a cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit (CSICU). Methods: A total of 134 patients hospitalized in CSICU from July, 2017 to September, 2019 were randomly allocated into control group and observation group, of which 64 in control group were given routine nursing care, and 70 in observation group were given humanized care additionally. The cardiopulmonary function, self-efficacy, SQ, incidence of adverse reactions, anxiety and depression, QOL, and patient satisfaction were evaluated. Results: After nursing, patients in the observation group showed enhanced cardiopulmonary function and self-efficacy, better SQ and QOL, as well as lower incidence of adverse reactions and anxiety and depression, and higher satisfaction. Conclusion: Humanized care contributes to the recovery of cardiopulmonary function, and is effective in alleviating anxiety and depression and enhancing self-efficacy, SQ and QOL of patients in CSICU.

Keywords: Humanized care, cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit, self-efficacy, sleep quality and quality of life

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including coronary heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, complex congenital heart disease and macrovascular diseases, are global health risks and the main causes of death worldwide [1,2]. High mortality rates and high costs make them a significant issue in medical care corresponding to an aging population. People are paying increasing attention to the prevention and treatment of CVDs and the management of medical care system. In particular, due to the integration of advanced technology and specialized human resources in cardiovascular surgery, medical services have become increasingly important in an effective health care system [3,4]. However, patients still have a great risk of recurrence after treatment, which not only induces inflammation in the kidneys or other organs, but even leads to death in severe cases [5,6], making pre-, intra- and post-operative nursing cares essential. In this present study, we enrolled patients in a cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit (CSICU) to discuss the influence of humanized care in CVDs.

Humanized care, defined by WHO as the process of communication and mutual support between individuals, aims at transforming and understanding the basic spirit of life. From the perspective of health care intervention, it has great potential for physical and emotional intimacy between patients and professionals, and between patients and their families [7,8]. From the perspective of psychology, it involves patients with psychological counseling, contributing to their recovery [9,10]. Studies show that humanized care plays a vital role in physical recovery and anxiety relief, so is has been widely used in postoperative care of various diseases worldwide [11,12]. Although frequently adopted in postoperative care of cardiovascular diseases at home and abroad, the specific role of humanized care has rarely been explored. In this study, we investigated its influence on CSICU patients in terms of self-efficacy, sleep quality (SQ), quality of life (QOL), and other indicators.

Materials and methods

General data

A total of 134 patients hospitalized in Jiangsu Province Hospital CSICU from July, 2017 to September, 2019 were randomly allocated into control group and observation group, of which 64 in control group were given routine nursing care, and 70 in observation group were given humanized care additionally. Patients and their families were informed of the procedure and signed the consent form. The study was performed with the approval of ethics Committee.

Inclusion criteria: patients diagnosed with CVDs [13]; patients without other diseases that have a major impact on our conclusions; patients with normal postoperative vital signs and no mental abnormalities; patients without communication disorders. Exclusion criteria: patients with other diseases that have a major impact on our conclusion; patients with dysfunctions of organs (the liver, kidney, heart, etc.); patients with mental disorders; pregnant or lactating women.

Methods

Patients in the control group received routine nursing care. Routine preoperative preparations, such as skin preparation, establishment of vascular access, skin test, were conducted. Patients and their families were informed about the time of operation to facilitate their preoperative preparations and alleviate the anxiety of patients. During the operation, the nursing staff actively cooperated with the doctor, and at the same time made detailed records and observations of the changes in vital signs, and immediately contacted the doctor in case of emergency. Afterwards, postoperative care was conducted strictly following the doctor’s advice.

The observation group adopted humanized care on the basis of routine nursing care. Medical staff carried out the necessary basic work before the operation at the right time and for the right length of time, for example, avoiding patients’ treatment and meal times. After a detailed investigation on medical records and other general data, the medical staff introduced themselves to patients and their families in an approachable tone. These measures were designed to allow more communication between medical staff and patients, and to relieve the pressure and enhance the confidence of patients. Health education, including the operating room environment, doctors’ information, procedures and precautions during operation, was carried out to make patients prepare psychologically in advance. Medical staff conducted physical and psychological tests to comfort patients with depression, anxiety and other negative emotions, so as to build their confidence and sense of security. The medical staff kept warm-hearted when the patients entered the operating room, then checked their general data. The operating room was kept bright, tidy, and quiet, with a temperature between 21°C-25°C and a humidity between 40-60%. During the operation, the patients were encouraged to actively communicate with the medical staff so that doctors can better understand their conditions. After the operation, the patients were sent back to the ward and informed about precautions. During the period of rehabilitation, routine greetings and examinations were performed every day, and targeted measures were taken according to their physical and psychological conditions.

Outcome measures

Cardiopulmonary function: On admission and after 7 days of nursing, the cardiopulmonary function of patients was recorded. Chest CT was performed, and the forced expiratory volume in the first second/forced vital capacity (FEVI/FVC) within 15 seconds and the 6-minute walking distance (6MWD) were calculated.

Self-efficacy: On admission, after 7 and 14 days of nursing, patients’ self-efficacy was compared. General Self-efficacy Scale (GSES) [14] was employed for self-efficacy evaluation. With a total score of 10-40, higher scores indicated higher levels of self-efficacy.

Sleep quality: On admission, after 7 and 14 days of nursing, the SQ of patients was compared by Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (0-21 points) [15]. A score of ≤7 indicated a high SQ, a score of >7 indicated a poor SQ; the higher the score, the worse the SQ.

Anxiety and depression: On admission and after 14 days of nursing, the anxiety and depression of patients were compared with the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) [16] and self-rating depression scale (SDS) [17], respectively. Both SAS and SDS included 20 items with a total score of 100. The higher the score, the worse the mental health of patients.

Quality of life: The QOL of patients was assessed by 36-item short form (SF-36) after 14 days of nursing, with the score proportional to QOL [18].

Incidence of adverse reactions: The incidence of adverse reactions, including pulmonary infection, chest discomfort, arrhythmia, and hemorrhage, was compared.

Patient satisfaction: A self-made satisfaction questionnaire was employed to estimate the satisfaction of patients with the nursing care. The total score was 100: 100-85, satisfied; >70, moderately satisfied; and <70, dissatisfied.

Statistical methods

SPSS 25.0 (Asia Analytics Formerly SPSS China) was used for statistical analysis. Counting data were analyzed with X2 test, and measurement data expressed by (X±S) were analyzed by t test. Values of P<0.05 were assumed to be statistically significant.

Results

General data

There was no significant difference in general data of sex, age, body mass index (BMI), history of smoking and alcohol drinking, and obesity between the two groups (P>0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

General data of patients

| Classification | Observation group (n=70) | Control group (n=64) | t/X2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.09 | 0.767 | ||

| Male | 42 (60.00) | 40 (62.50) | ||

| Female | 28 (40.00) | 24 (37.50) | ||

| Age (years) | 43.96±7.41 | 44.21±7.17 | 0.20 | 0.843 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.87±2.65 | 27.32±2.86 | 0.95 | 0.346 |

| Classification of diseases | 1.13 | 0.567 | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 35 (50.00) | 28 (43.75) | ||

| Rheumatic heart disease | 28 (40.00) | 24 (37.50) | ||

| Aneurysm | 7 (10.00) | 10 (18.75) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.28 | 0.594 | ||

| Yes | 59 (84.29) | 56 (87.50) | ||

| No | 11 (15.71) | 8 (12.50) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.49 | 0.486 | ||

| Yes | 60 (85.71) | 52 (81.25) | ||

| No | 10 (14.29) | 12 (18.75) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.42 | 0.518 | ||

| Yes | 49 (70.00) | 48 (75.00) | ||

| No | 21 (30.00) | 16 (25.00) |

Enhanced cardiopulmonary function in observation group

Comparison of indexes of cardiopulmonary function revealed that the FEV1/FVC and 6MWD levels in the two groups increased evidently after nursing (refers to postoperative nursing), and in observation group were remarkably higher than those in control group (P<0.05) (Figure 1). Therefore, humanized care improves cardiopulmonary function more significantly than routine care.

Figure 1.

Cardiopulmonary function of patients. A. FEV1/FVC: FEV1/FVC level of patients in two groups increase significantly after nursing, and the observation group is significantly higher than the control group (P<0.05); B. 6MWD: 6MWD level in observation group is significantly higher than that in control group after nursing (P<0.05). Note: *P<0.05 vs. on admission, #P<0.05 vs. control group. FEV1/FVC: forced expiratory volume in the first second/forced vital capacity (FEVI/FVC); 6MWD: 6-minute walking distance.

Better recovery of self-efficacy in observation group

GSES scores in the two groups increased evidently after 7 and 14 days of nursing, and the observation group was remarkably higher than the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 2). Therefore, humanized care is associated with better self-efficacy.

Figure 2.

Self-efficacy of patients. GSES scores in the two groups increase evidently after 7 and 14 days of nursing, and the observation group is remarkably higher than the control group. Note: *P<0.05 vs. on admission, #P<0.05 vs. control group, ^P<0.05 vs. after 7 days of nursing.

Better recovery of SQ in observation group

PSQI scores in the two groups decreased evidently after 7 and 14 days of nursing, and the observation group was remarkably lower than the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 3). This indicates that humanized care enhances the SQ of patients in CSICU.

Figure 3.

Sleep quality of patients. PSQI scores in two groups decrease significantly after 7 and 14 days of nursing, and the observation group is remarkably lower than the control group (P<0.05). Note: *P<0.05 vs. on admission, #P<0.05 vs. control group, ^P<0.05 vs. after 7 days of nursing.

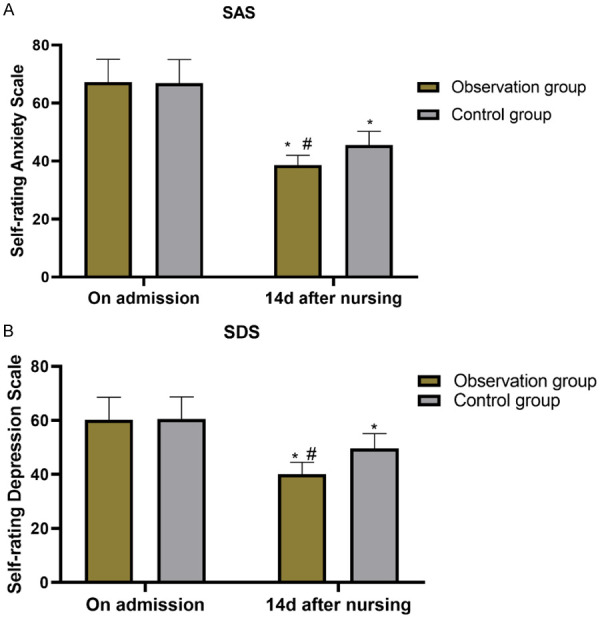

Lower anxiety and depression in observation group

Scores of SAS and SDS in the two groups decreased evidently after 14 days of nursing, and the observation group was remarkably lower than the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 4). So patients receiving humanized care have alleviated depression and improved mental health.

Figure 4.

SAS and SDS scores of patients. A. SAS: SAS score decreases significantly in the two groups after nursing, and the observation group is significantly lower than the control group (P<0.05); B. SDS: SDS score decreases significantly in the two groups after nursing, and the observation group is significantly lower than the control group (P<0.05). Note: *P<0.05 vs. on admission, #P<0.05 vs. control group. SAS: Self-rating anxiety scale; SDS: Self-rating depression scale.

Higher quality of life in observation group

Comparison of QOL demonstrated that the SF-36 score in observation group was remarkably higher than that in the control group (P<0.05) (Table 2), suggesting improved QOL of patients in the observation group.

Table 2.

SF-36 score of patients

| Classification | Observation group (n=80) | Control group (n=50) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 71.54±5.87 | 65.43±4.58 | 6.67 | <0.001 |

| Psychological functioning | 79.27±7.39 | 62.69±3.43 | 16.40 | <0.001 |

| Social functioning | 73.51±4.67 | 66.42±3.32 | 10.04 | <0.001 |

| Emotional functioning | 81.43±7.34 | 72.21±5.67 | 8.08 | <0.001 |

Lower incidence of adverse reactions in observation group

The adverse reactions of chest discomfort, arrhythmia, pulmonary infection and hemorrhage were monitored. It turned out that the incidence of adverse reactions in observation group was remarkably lower than that in control group (P<0.05) (Table 3). This led to the conclusion that patient safety is more effectively guaranteed by humanized care, which resulted in greatly reduced adverse reactions.

Table 3.

Incidence of adverse reactions

| Classification | Observation group (n=70) | Control group (n=64) | X2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest discomfort | 1 (1.43) | 4 (6.25) | - | - |

| Arrhythmia | 1 (0.00) | 3 (4.69) | - | - |

| Pulmonary infection | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.56) | - | - |

| Hemorrhage | 0 (1.43) | 4 (6.25) | - | - |

| Incidence of adverse reactions (%) | 2 (2.86) | 12 (18.75) | 9.03 | 0.003 |

Higher patient satisfaction in observation group

Patients in observation group were more satisfied with the nursing than those in control group (P<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Satisfaction of patients

| Classification | Observation group (n=70) | Control group (n=64) | X2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied | 42 (60.00) | 24 (37.50) | - | - |

| Moderately satisfied | 21 (30.00) | 24 (37.50) | - | - |

| Dissatisfied | 7 (10.00) | 16 (25.00) | - | - |

| Satisfaction rate (%) | 63 (90.00) | 48 (75.00) | 5.29 | 0.021 |

Discussion

Surgical treatment is a crucial intervention for CSICU patients to relieve symptoms of CVDs and improve their QOL [19], however, it may lead to high mortality [20]. To minimize damages caused by surgery, the selection of pre-, intra- and post-operative nursing cares is of great significance. From the anxiety and depression recovery, as well as the physical recovery of patients, we discussed the influence of humanized care.

The scores of SAS and SDS (anxiety and depression recovery) in observation group adopting humanized care were remarkably lower than those in the control group. CVDs not only lead to a decline of patients’ self-care ability, but also induce depression and cognitive dysfunction, resulting in their pessimistic attitude toward life [21-23]. Besides, if patients with CVDs are depressed and anxious, the demand for nursing care will increase, which will also bring new challenges to their families [24]. Although traditional nursing care plays a role in easing the tension of patients, many problems remain unsolved, along with inadequate nurse-patient communication, resulting in the improvement of negative emotions being inferior to that of other nursing modes [25,26]. In the present study, because nurse-patient communication in the control group was not as much as that in the observation group, negative emotions were not alleviated significantly. Effective communication is very important in all nursing modes, especially in humanized care, which not only enables patients rebuild their confidence and dignity, but also reduces their negative emotions [27]. Therefore, the anxiety and depression of patients in the observation group were greatly relieved.

The cardiopulmonary function and self-efficacy of patients in observation group were enhanced after nursing (physical recovery). Negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, can only lead to aggravation of diseases ande deterioration of related indicators, so a more optimistic mentality makes patients recover from diseases faster [28]. Self-efficacy, the most primary determinant of the emergence and change of behavior, is regulated by CVD-induced pain and pain-induced depression [29]. Better recovery of from depression, coupled with pre- and intra-operative health education, helped patients in the observation group make fewer mistakes, leading to their better recovery of self-efficacy. This also means that they can act and change their actions more autonomously after surgery. 6MWD is a repeatable, simple and cheap test used as a function indicator of patients with CVDs and pulmonary diseases. It objectively measures the ability to perform daily activities and the recovery of exercise endurance of patients with chronic heart failure or other CVDs [30]. The increase of FEV1/FVC indicates the good restoration of patients’ respiratory function [31]. A study on the treatment of bedsores with wet healing therapy reports that humanized care facilitates the treatment, significantly relieves symptoms, and reduces the area of pressure sores [32], which is similar to our results. In the present study, the patients in the observation group recovered better from the surgery. In addition, the recovery of self-efficacy, respiratory and cardiac functions portended higher SQ and QOL. Also, health education and communication before and during the surgery enhanced the confidence of patients, and achieved a tacit understanding between the patients and the medical staff. This facilitates the medical staff to play a better role in the surgery, which reduces the incidence of postoperative adverse reactions in the observation group.

One of the limitations of this study lies in that we failed to test the patients’ compliance. In the future research, we will make statistical comparison on patients’ compliance in order to improve nursing measures. Besides, it is necessary to determine the inflammatory factors and related signal pathways to better analyze our results.

To sum up, humanized care contributes to the recovery of cardiopulmonary function, and is effective in alleviating anxiety and depression and enhancing self-efficacy, SQ and QOL of patients in CSICU.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosala Nezhad Z, Poncelet A, de Kerchove L, Gianello P, Fervaille C, El Khoury G. Small intestinal submucosa extracellular matrix (CorMatrix(R)) in cardiovascular surgery: a systematic review. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;22:839–850. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivw020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pimpin L, Wu JH, Haskelberg H, Del Gobbo L, Mozaffarian D. Is butter back? A systematic review and meta-analysis of butter consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and total mortality. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim M, Yoon SJ, Choi JS, Kim MJ, Sim SB, Lee KS, Chee HK, Park NH, Park CS. Imbalance in cardiovascular surgery medical service use between regions. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;49:S14–S19. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2016.49.S1.S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanon S, Lee VV, Elayda MA, Gondi S, Livesay JJ, Reul GJ, Wilson JM. Predicting early death after cardiovascular surgery by using the Texas Heart Institute Risk Scoring Technique (THIRST) Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:156–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu J, Chen R, Liu S, Yu X, Zou J, Ding X. Global incidence and outcomes of adult patients with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30:82–89. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvin IM, Leitch J, Gill R, Poser K, McKeown S. Humanization of critical care psychological effects on healthcare professionals and relatives: a systematic review. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:1348–1371. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Y, Liu C, Guo B, Zhao L, Lou F. The impact of emotional intelligence on work engagement of registered nurses: the mediating role of organisational justice. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2115–2124. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Fuentes MDC, Jurado M, Gazquez Linares JJ. Explanatory value of general self-efficacy, empathy and emotional intelligence in overall self-esteem of healthcare professionals. Soc Work Public Health. 2019;34:318–329. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2019.1606752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Fuentes MDC, Herrera-Peco I, Molero Jurado MDM, Oropesa Ruiz NF, Ayuso-Murillo D, Gazquez Linares JJ. A cross-sectional study of empathy and emotion management: key to a work environment for humanized care in nursing. Front Psychol. 2020;11:706. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beltran Salazar OA. The meaning of humanized nursing care for those participating in it: importance of efforts of nurses and healthcare institutions. Invest Educ Enferm. 2016;34:18–28. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v34n1a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos BMD, Silva R, Pereira ER, Joaquim FL, Goes TRP. Nursing students’ perception about humanized care: an integrative review. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71:2800–2807. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcarea A, Sovaila S, Udrea G, Rezus E, Gheorghe A, Tiu C, Stoica V. Utility of different cardiovascular disease prediction models in rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Life. 2014;7:588–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crandall A, Rahim HF, Yount KM. Validation of the general self-efficacy scale among qatari young women. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;21:891–896. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.12.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mollayeva T, Thurairajah P, Burton K, Mollayeva S, Shapiro CM, Colantonio A. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:52–73. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Jin D, Qiao F, Chen J, Gong J. Relationship between the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale score and the success rate of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2016;51:47–55. doi: 10.1177/0091217415621265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jokelainen J, Timonen M, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Harkonen P, Jurvelin H, Suija K. Validation of the Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS) in older adults. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37:353–357. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1639923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunevicius A. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire in patients with brain tumors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:92. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0665-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eghbali-Babadi M, Shokrollahi N, Mehrabi T. Effect of family-patient communication on the incidence of delirium in hospitalized patients in cardiovascular surgery ICU. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2017;22:327–331. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.212985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DJ, Park KH, Isamukhamedov SS, Lim C, Shin YC, Kim JS. Clinical results of cardiovascular surgery in the patients older than 75 years. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;47:451–457. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2014.47.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyagenda JO, Ddumba E, Odokonyero R, Kaddumukasa M, Sajatovic M, Smyth K, Katabira E. Post-stroke depression among stroke survivors attending two hospitals in Kampala Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:1220–1231. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i4.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi MC, Chu FN, Li C, Wang SC. Thrombolysis in acute stroke without angiographically documented occlusion. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:1509–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein BI, Carnethon MR, Matthews KA, McIntyre RS, Miller GE, Raghuveer G, Stoney CM, Wasiak H, McCrindle BW American Heart Association Atherosclerosis; Hyperten-sion and Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder predispose youth to accelerated atherosclerosis and early cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:965–986. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carvalho IG, Bertolli ED, Paiva L, Rossi LA, Dantas RA, Pompeo DA. Anxiety, depression, resilience and self-esteem in individuals with cardiovascular diseases. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2016;24:e2836. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.1405.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan D, Han L, Qu W, Tian S, Li Z, Zhang W, Xu L, Gao H, Zhang N. Comprehensive nursing based on feedforward control and postoperative FMA and SF-36 levels in femoral intertrochanteric fracture. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2019;19:516–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortega Barco MA, Munoz de Rodriguez L. Evaluation of the nursing care offered during the parturition process. Controlled clinical trial of an intervention based on Swanson’s theory of caring versus conventional care. Invest Educ Enferm. 2018;36:e05. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v36n1e05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franca JR, da Costa SF, Lopes ME, da Nobrega MM, de Franca IS. The importance of communication in pediatric oncology palliative care: focus on humanistic nursing theory. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21:780–786. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692013000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell R, Scott NW, Manyande A, Bruce J, Vogele C, Byrne-Davis LM, Unsworth M, Osmer C, Johnston M. Psychological preparation and postoperative outcomes for adults undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD008646. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008646.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruber-Baldini AL, Velozo C, Romero S, Shulman LM. Validation of the PROMIS((R)) measures of self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:1915–1924. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1527-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal MB, Awad NT. Correlation between six minute walk test and spirometry in chronic pulmonary disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:OC01–04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13181.6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho O, Oh YT, Chun M, Noh OK, Heo JS. Prognostic implication of FEV1/FVC ratio for limited-stage small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:1797–1805. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.02.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luan XR, Li WH, Lou FL. Applied analysis of humanized nursing combined with wet healing therapy to prevent bedsore. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:4162–4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]