Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Sarcopenia is associated with decreased survival in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. This study sought to determine whether in-clinic multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) can identify survival-associated sarcopenia in patients with head and neck cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This prospective observational study enrolled 50 patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Baseline BIA measures of skeletal muscle (SM) mass, fat-free mass (FFM), and fat mass (FM) were compared to CT-based estimates using linear regression. Sex-specific BIA-derived thresholds for sarcopenia were defined by the maximum Youden Index on receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves. Patients were stratified by sarcopenia status and OS was compared using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test.

RESULTS:

Among 48 evaluable patients, BIA measures of body composition were strongly correlated with CT measures: SM mass (r = 0.97; R2 = 0.94; p < 0.0001), FFM (r = 0.97; R2 = 0.94; p < 0.0001) and FM (r = 0.95; R2 = 0.90; p < 0.0001). SM mass index < 9.19 kg/m2 identified sarcopenia men with high sensitivity (91.7%) and specificity (92.9%), whereas in women SM mass index < 6.53 kg/m2 was sensitive for sarcopenia (100%), but not specific. Patients with sarcopenia, defined by either CT or BIA, exhibited decreased OS (HR=not estimable; CT p = 0.009; BIA p = 0.03).

CONCLUSION:

BIA provides accurate estimates of body composition in head and neck cancer patients. Implementation of BIA in clinical practice may identify patients with sarcopenia at risk for poor survival.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, radiotherapy, sarcopenia, cachexia, bioelectrical impedance analysis, cancer, oropharyngeal

Introduction

Head and neck cancer patients with decreased muscle mass, or sarcopenia, exhibit poor survival and locoregional cancer control as well as impaired tolerance of radiotherapy (RT) and increased chemotherapy toxicity [1–6]. Weight loss itself shows little correlation with oncologic or functional outcomes, and weight-derived metrics, such as body mass index (BMI), are unable to differentiate between the lean and adipose contributions to body mass [7]. The gold standard for body composition measurement is dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), with more recent data validating the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or CT [8–10]. However, these modalities are expensive, involve radiation exposure (in the case of CT and DXA), and are often not pragmatic or available at radiation treatment centers. Furthermore, body composition analysis of CT or MRI scans is not routinely performed, so this information is unavailable for clinical use. Therefore, there is a need for body composition evaluation that can be rapidly implemented into routine clinical workflow.

BIA offers a non-invasive, cost-effective method for serially measuring body composition [11]. BIA measures an individual’s resistance to a weak electric current, from which fat (FM) and fat free mass (FFM) can then be estimated using empirically derived equations. BIA body composition values depend upon patient and electrode positioning, the frequency or frequencies of current, and the equation used to impute body composition [12]. Early studies found strong linear correlation between BIA and DXA in cancer patients, but broad limits of agreement, calling into question the clinical utility of estimating body composition with BIA (reviewed in [13]). More recent BIA platforms utilize designs that control for patient and electrode position and measure impedance at multiple frequencies in an effort to improve accuracy [14]. One such platform reported that BIA estimates of body composition in a healthy patient population did not differ significantly from estimates derived from the four-compartment model across multiple ethnic groups [14]. Patients with head and neck cancer represent a more challenging population given wide fluctuations in hydration status, nutrition, and muscle mass. Prior studies demonstrated utility of the direct BIA measures of phase angle and membrane capacitance in predicting survival among head and neck cancer patients, suggesting prognostic value of BIA in this population [15–20]. More recently, BIA was validated against DXA for the estimation of FFM in patients with head and neck cancers, demonstrating high concordance, but also relatively broad limits of agreement corresponding to ~7% of total FFM [21]. A similar study in patients with colorectal cancer showed that BIA could identify patients with malnutrition, defined by DXA FFM thresholds, with sensitivity and specificity >90% [22]. These studies suggest that BIA may also be able to accurately discriminate patients with low muscle mass.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether BIA can be used to identify sarcopenia associated with decreased survival in patients with head and neck cancer treated with RT. We first evaluated the concordance between eight-electrode multifrequency BIA, measured using the SECA medical Body Composition Analyzer (mBCA) 515 scale, and CT-based estimates of body composition. CT-based estimates were selected as the reference standard due to the previously described association between this measure of body composition and survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Secondary objectives were to serially examine the change in weight and body composition during RT using BIA.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Between February 2016 and March 2017, 50 patients were enrolled at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center during their treatment planning visits. Patients eligible for enrollment were age ≥ 18 years with pathologically confirmed head and neck cancer, AJCC 7th edition stage Tx-T4, N0–3, M0, dispositioned to RT to a dose of ≥ 60 Gy either as single modality or as part of a multimodality treatment approach. Additionally, they required a staging PET/CT scan within a 30-day period prior to initiation of RT. Exclusion criteria included prior overlapping RT, pregnancy, or concomitant medical conditions known to cause cachexia or sarcopenia, including NYHA class III-IV heart failure, oxygen-dependent pulmonary disease, advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, cirrhosis, end stage renal disease, or inherited/congenital disorders of metabolism. All patients underwent treatment per consensus recommendation by multidisciplinary tumor board, without regard for study inclusion. Patient demographics and treatment and tumor characteristics were abstracted from the electronic medical record. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to the date of death due to any cause. Chemotherapy completion was defined as having received all intended concurrent chemotherapy treatments without dose reduction, delay, or omission. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Treatment characteristics

All patients were treated utilizing an intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) technique using 6 MV photons. Treatments were planned using Pinnacle radiation planning system (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) and delivered with either static gantry approach consisting of 9 static gantry beams spaced at 40-degree intervals or volumetric modulated arc therapy, consisting of 2 arcs. In general, 3 clinical treatment volumes (CTVs) were defined for each patient: CTV1, which included gross disease or preoperative tumor bed with a margin; CTV2, which included the neck volume at high risk of harboring microscopic disease; and CTV3, the elective nodal volume at low risk of harboring microscopic disease. Patients were dispositioned to concurrent receipt of chemotherapy based on the recommendations of multidisciplinary tumor board. Concurrent chemotherapy doses and schedules are as follows: cisplatin 40 mg/m2 weekly or 100 mg/m2 delivered every three weeks; carboplatin AUC 2 weekly; cetuximab 400 mg/m2 loading dose one week prior to RT start followed by 250 mg/m2 delivered weekly; carboplatin 100 mg/m2 and paclitaxel 40 mg/m2 weekly. All patients received pre-RT speech and swallow evaluations and weekly dietary counseling. Feeding tubes were provided per clinician judgement during treatment and were not offered prophylactically.

Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis

Body composition was measured using the FDA-cleared SECA mBCA 515 scale (https://www.seca.com/en_no/products/all-products/product-details/seca515.html; seca gmbh & co. kg, Hamburg, Germany; Supplementary Figure 1). One of three possible hand positions was selected such that the angle between the body and arms was as close to 30 degrees as possible. Impedance is measured using a 100 μA current delivered at 19 frequencies ranging from 1–1000 kHz [14]. To avoid additional barriers to adequate nutrition and exercise, participants were instructed to not alter their food intake or activity prior to measurement. Estimations of body composition were based on equations previously validated in healthy adults and incorporated into SECA analytics 115 software (SECA North America, Chino, CA) [14]. BIA data were measured prior to RT initiation (baseline), then at weekly clinic visits during treatment. Measurements were stored outside the patients’ medical records and were not used for medical decision making.

CT Image Analysis

Cross-sectional images of the third lumbar vertebrae (L3) were extracted from the CT component of pre-RT whole-body diagnostic PET-CT scans for each participant [9, 23–25]. Both SM mass and FM were calculated from L3 contours, as previously described [9]. The mean cross-sectional area of muscle and adipose tissue was divided by the square of height in meters to normalize for patient height and reported as the lumbar SM index (SMI) or adipose index (ADI) [9, 23, 25]. SM depletion was defined a priori as an SMI of less than 52.4 for men and less than 38.5 for women [1, 25, 26].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test and differences between groups were assessed using the 2-tailed Student’s t test (for normally distributed continuous variables), Mann Whitney test (for non-normally distributed continuous variables), and Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s Exact Test (for categorical variables). Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier technique. We used the log-rank test to compare survival between groups of patients. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, using two-sided tests. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP (version 15; SAS Institute, Inc.).

For the primary outcome, we used linear regression analysis to determine the correlation between baseline lean body mass and fat mass predicted from impedance measurement and CT imaging. The Pearson correlation, r, between BIA and CT imaging estimates of lean and fat body mass before RT as well as the coefficient of determination, R2, were calculated. Both sexes were included in correlation calculations as these relationships are age and sex invariant [8]. RMSE analysis was utilized to quantify the average error from BIA-derived body composition calculations. SM mass, FFM, and FM estimates were calculated from BIA using the manufacturer’s previously validated formulae [14] and compared against CT-measured tissue Cross-Sectional Area (CSA). Comparisons of SM mass for each body segment (torso, R & L legs, R & L arms) were repeated against whole body L3 CT CSA. Height-normalized BIA estimates were compared against CT-derived SMI and ADI as well as BMI. To identify BIA-based thresholds for sarcopenia, ROC analyses were performed using the sex-specific CT-based sarcopenia definitions described above as ground truth. BIA sarcopenia thresholds were defined by identifying the optimal threshold from the ROC analyses based on maximum Youden Index—the value of the tested variable at which the sum of sensitivity and specificity is greatest. Sensitivity and specificity were then calculated for each regressor using the optimized threshold. To evaluate whether weight loss during RT reflects changes in body composition, the changes in each BIA-measured tissue compartment and BMI were calculated by subtracting the baseline value from the measurement during the final week of treatment. R2 and RMSE were calculated from linear regression analysis comparing change in SM mass, FFM, and FM to change in BIA.

Results

Fifty patients were enrolled, and 48 patients remained in the study and evaluable. Two patients withdrew consent to the study prior to data collection, and two patients requested to withdraw from the study because their treatment occurred offsite; their baseline data were included in analysis. Patients had a mean age of 60 ± 12 years at enrollment. The patient sample was predominately male (40 men [83%] vs 8 women [17%]) with mean BMI of 30 ± 5 kg/m2 for men and 24 ± 5 kg/m2 for women. The oropharynx was the most common primary cancer site, with 26 cases (54%). The majority of patients (28 [58%]) had multiple involved lymph nodes at diagnosis (AJCC 7th edition N2–3). Human papillomavirus was detected by p16 immunohistochemistry or HPV polymerase chain reaction in all 26 oropharynx cancer patients (54%) and was not tested in 19 other patients (40%). Forty-seven of 48 patients (98%) had ECOG PS 0–1. Patient and treatment characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient and Treatment Characteristics.

Separated by sex. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; CUP, cancer of unknown primary; HPV, human papillomavirus; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; SM, skeletal muscle. P-values calculated using Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney test for continuous variables, χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test for categorical variables.

| mean | Men (n = 40, 83%) SD | mean | Women (n = 8, 17%) SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 60 | 11 | 52 | 17 | 0.23 |

| Height (m) | 1.79 | 0.06 | 1.61 | 0.06 | <.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 97 | 17 | 63 | 12 | <.0001* |

| BM (kg/m2) | 30 | 5 | 24 | 5 | 0.02 |

| RT | |||||

| Dose (Gy) | 68 | 3 | 67 | 4 | 0.19* |

| Fractions | 32 | 2 | 32 | 2 | 0.71* |

| Package time (d) | 42 | 3 | 43 | 4 | 0.54* |

| No. | % | No. | % | P | |

| Cancer Site | 0.54 | ||||

| Nasopharynx | 2 | 5 | 1 | 13 | |

| Oropharynx | 24 | 60 | 2 | 25 | |

| Glottis | 4 | 10 | 1 | 13 | |

| CUP | 2 | 5 | 2 | 25 | |

| Sinonasal | 2 | 5 | 1 | 13 | |

| Skin | 2 | 5 | - | - | |

| Salivary Gland | 1 | 3 | 1 | 13 | |

| T stage | 0.57 | ||||

| TX | 2 | 5 | - | - | |

| T0–2 | 28 | 70 | 5 | 63 | |

| T3–4 | 10 | 25 | 3 | 38 | |

| N stage | 0.04 | ||||

| N0–1 | 14 | 35 | 6 | 75 | |

| N2–3 | 26 | 65 | 2 | 25 | |

| Grade | 0.11 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mod differentiated | 12 | 30 | 2 | 25 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 15 | 38 | 1 | 13 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 23 | 5 | 63 | |

| HPV-status | 0.53 | ||||

| Positive | 23 | 58 | 3 | 38 | |

| Negative | 2 | 5 | 1 | 13 | |

| Not tested | 15 | 38 | 4 | 50 | |

| ECOG PS | 0.18 | ||||

| 0 | 25 | 63 | 6 | 75 | |

| 1 | 13 | 33 | 1 | 13 | |

| 2 | - | - | 1 | 13 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 5 | - | - | |

| SM depleted* | 0.28 | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 30 | 4 | 50 | |

| No | 28 | 70 | 4 | 50 | |

| RT indication | 0.82 | ||||

| Definitive | 33 | 79 | 6 | 75 | |

| Adjuvant | 9 | 21 | 2 | 25 | |

| Concurrent chemoRT | 0.70 | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 67 | 5 | 63 | |

| No | 14 | 33 | 3 | 38 | |

| Concurrent chemo type | 0.05 | ||||

| Weekly cetuximab | 9 | 21 | 1 | 13 | |

| Weekly cisplatin | 12 | 29 | 1 | 13 | |

| Weekly carboplatin | 3 | 7 | 2 | 25 | |

| Cisplatin q3w | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| Induction chemotherapy | 0.22 | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 10 | - | - | |

| No | 36 | 90 | 8 | 100 | |

, Mann Whitney test.

At the time of enrollment, no patients were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), 8 patients (17%) had normal BMI (18.5–24.9), 23 patients (48%) were overweight (BMI 25–29.9), and 17 patients (35%) were obese (BMI - 30). By CT analysis, 16 patients (33%) were sarcopenic at the time of enrollment. Full body composition details measured by CT and BIA are shown in Table 2. Age, height, tumor site, T stage, N stage, grade, HPV status, smoking status, and use of induction chemotherapy did not vary by sarcopenic status (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2. Pre-treatment Body Composition.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CT, computed tomography; CSA, cross sectional area; SMI, skeletal muscle index; SM, skeletal muscle; ADI, adipose index; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; FFM, fat free mass. Data represent mean ± SD. P-values calculated using Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney test for continuous variables, χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test for categorical variables.

| Body Composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=48 | Male N=40 | Female N=8 | P-value (sex) | |

| BMI categories, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| <18.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 8 (17%) | 3 (7.5%) | 5 (62%) | |

| 25–29.9 | 23 (48%) | 22 (55%) | 1 (13%) | |

| ≥30 | 17 (35%) | 15 (37.5%) | 2 (25%) | |

| CT measures, mean ± SD | ||||

| L3 Muscle CSA (cm2) | 166 ± 41 | 179 ± 30 | 99 ± 13 | <.0001 |

| SMI (cm2/m2) | 53 ± 10 | 56 ± 8 | 39 ± 5 | <.0001 |

| Sarcopenia, n (%) | 16 (33%) | 12 (30%) | 4 (50%) | 0.41 |

| L3 Fat CSA (cm2) | 346± 135 | 354± 135 | 305 ±138 | 0.34* |

| ADI (cm2/m2) | 113 ± 45 | 111 ± 43 | 120 ± 58 | 0.62* |

| BIA measures, mean ± SD | ||||

| SM mass (kg) | 29 ± 7 | 32 ± 5 | 17 ± 3 | <.0001 |

| SM mass (% body weight) | 15 ± 2% | 16 ± 1.4% | 12 ± 2% | 0.002 |

| SM mass index (kg/m2) | 9 ± 2 | 9.9 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | <.0001 |

| Fat free mass (kg) | 61 ± 12 | 65 ± 8 | 39 ± 4 | <.0001 |

| Fat free mass (% body weight) | 67 ± 7% | 68 ± 6% | 63 ± 9% | 0.2 |

| FFM index (kg/m2) | 19 ± 3 | 20 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | <.0001 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 30 ± 11 | 32 ± 10 | 24 ± 10 | 0.06* |

| Fat mass (% body weight) | 33 ± 7% | 32 ± 6% | 37 ± 9% | 0.2 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | 10 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 | 9 ± 4 | 0.74 |

, Mann Whitney test.

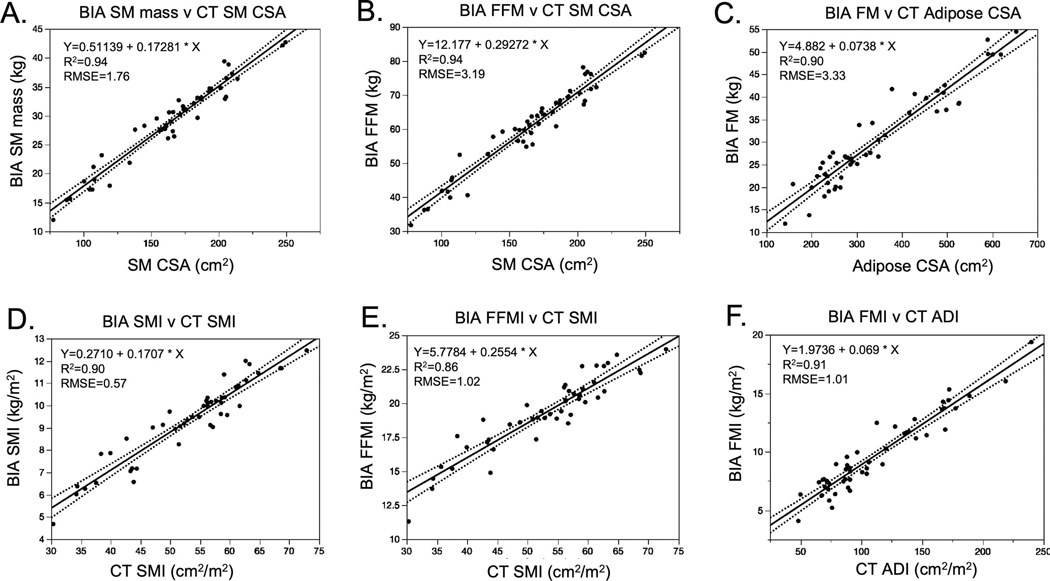

To determine whether BIA could accurately replicate CT-derived body composition metrics, we conducted a series of linear regressions. We first evaluated the relationships between BIA measures of SM mass, FFM, and FM against unnormalized CT-derived SM and adipose CSA (Figure 1). BIA SM mass was highly correlated to CT SM CSA with SM mass (kg) = 0.511 + 0.173 x [SM CSA at L3 (cm2)], r = 0.97; p < 0.0001. BIA FFM was also closely associated with CT SM CSA; FFM (kg) = 12.18 + 0.293 x [SM CSA at L3 (cm2)], r = 0.97; p < 0.0001. BIA accurately represented CT measures of fat mass; FM mass (kg) = 4.882 + 0.074 x [Adipose CSA at L3 (cm2)], r = 0.95; p < 0.0001.

Figure 1. BIA measures of body composition compared to CT-based estimates and BMI.

A, Skeletal Muscle (SM), B, Fat Free Mass (FFM) and C, Fat Mass (FM) measured by BIA compared to SM and FM estimates derived from lumbar CT scans. Normalized measures of body composition D, Skeletal Muscle Index (SMI), E, Fat Free Mass Index (FFMI) and F, Fat Mass Index (FMI) measured by BIA compared to SMI and adipose index (ADI) estimates derived from lumbar CT scans.

Because thresholds for survival-associated sarcopenia are based on normalized body composition indices, we repeated these correlations using normalized tissue compartment measures. For BIA, this includes the SM index (SMI), FFM index (FFMI), and FM index (FMI), each of which is automatically calculated by dividing the measured mass value by the square of height in meters. Linear regression revealed close associations between BIA and CT (Figures 1D–1F):

BIA SMI (kg/m2) = 0.271 + 0.171 x [CT SMI (kg/m2)]; r = 0.95, p < 0.0001

BIA FFMI (kg/m2) = 5.778 + 0.255 x [CT SMI (kg/m2)]; r = 0.93, p < 0.0001

BIA FMI (kg/m2) = 1.974 + 0.069 x [CT ADI (kg/m2)]; r = 0.95, p < 0.0001

We then tested the association between BIA measures of body composition and BMI, to identify which tissue compartments are best estimated by BMI. BIA measures were less closely associated with BMI than CT, with the strongest association seen between BIA FMI and BMI (Supplementary Figures 2A-2C).

Having observed close correlation between BIA and CT measured SM mass estimates, we then sought to use these relationships to define sex-specific BIA cutoffs for sarcopenia. For men, optimal cutoffs for SM mass and FFM, both raw and normalized to the square of height in meters, demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for defining sarcopenia, as evidenced by ROC c-statistics > 0.92 (Table 3). The best discriminator for sarcopenia, as defined by the highest ROC c-statistic, was SM mass index < 9.2 kg/m2 for men (c-statistic 0.96, sensitivity 92%, specificity 93%). Analysis of the optimized cutoff in women was limited by the small number of women in the study. Despite this, discriminatory performance was also highest when using SM mass index < 6.5 kg/m2 (c-statistic 1.0, sensitivity 100%, specificity 0%).

Table 3.

BIA measures of SM depletion.Receiver operator curve analysis to identify optimal sex-specific BIA thresholds for SM depletion. Sensitivity and specificity reflect values at the maximum Youden Index for each regressor. Abbreviations: SM, skeletal muscle; FFM, fat free mass.

| Male N=40 | Female N=8 | |||||||||

| Measure | Youden Index | Sarcopenia Threshold | c-statistic | sensitivity | specificity | Youden Index | Sarcopenia Threshold | c-statistic | sensitivity | specificity |

| SM mass (kg) | 0.82 | 31 | 0.93 | 100% | 82% | 0.75 | 16 | 0.81 | 75% | 0% |

| SM mass (% body weight) | 0.35 | 14% | 0.57 | 33% | 93% | 0.25 | 13% | 0.50 | 50% | 25% |

| SM mass index (kg/m2) | 0.85 | 9.2 | 0.96 | 92% | 93% | 1.0 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 100% | 0% |

| Fat free mass (kg) | 0.82 | 62 | 0.93 | 100% | 82% | 0.75 | 36 | 0.81 | 75% | 0% |

| FFM index (kg/m2) | 0.79 | 20 | 0.94 | 100% | 89% | 0.75 | 14 | 0.94 | 100% | 25% |

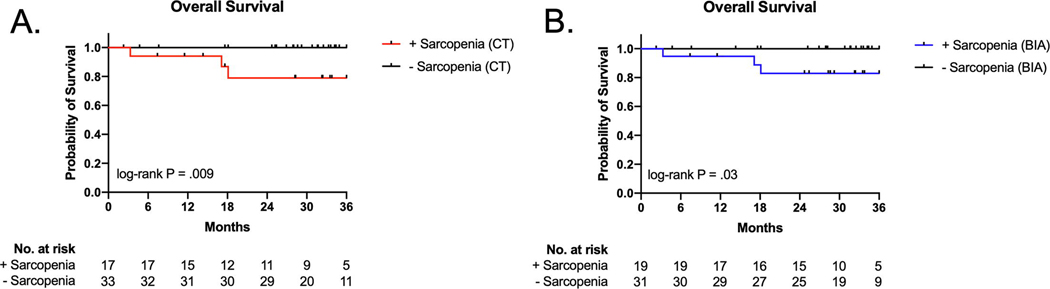

With a median follow up of 31 months [interquartile range: 23 months, 36 months], patients who had CT-defined sarcopenia at the time of diagnosis exhibited poorer survival (hazard ratio not assessable due to absence of events in one group, log-rank P = 0.009, Figure 2A), consistent with prior reports [1–3]. When BIA was used to define sarcopenia, utilizing the optimal thresholds described above, again sarcopenia was associated with poorer survival (hazard ratio not assessable, log-rank P = 0.03, Figure 2B). All deceased patients were sarcopenic by both measures at the time of diagnosis. There was no difference in RT dose, fractionation, package time, the proportion of patients dispositioned to concurrent chemoradiation or the proportion of patients whose chemotherapy regimen was delayed, dose reduced, or abridged (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. The effect of sarcopenia at diagnosis on overall survival.

A, Patients with sarcopenia on presentation, measured using CT imaing, demonstrated decreased overall survival compared with patients with normal SMI. B, Patients with BIA-defined sarcopenia on presentation also demonstrated decreased overall survival compared with patients with a normal SM mass index.

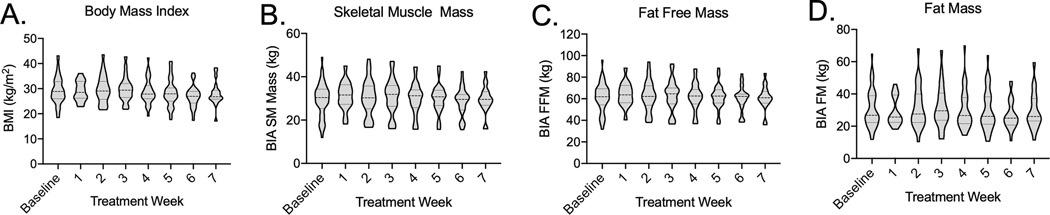

Patients lost an average of 6 ± 6 kg during treatment, with mean BMI dropping from 29 ± 6 kg/m2, to 28 ± 5 kg/m2 at treatment completion (Figure 3A). SM mass decreased by a mean of 2 ± 2 kg during treatment from 30 ± 8 kg to 28 ± 7 kg (Figure 3B). FFM decreased by a mean of 3 ± 3 kg from a mean of 62 ± 13 kg to 59 ± 12 kg (Figure 3C). Mean FM loss was 2 ± 3 kg, from an initial mean FM of 31 ± 12 kg to 29 ± 11 kg (Figure 3D). Patients lost an average of 0.8 ± 1.8 kg of total body water during RT. Eight patients crossed below the above-defined BIA thresholds for sarcopenia during RT. There were no deaths among this subpopulation of patients.

Figure 3. Body composition measures during treatment.

Violin plot showing distribution of A, BMI, B, SM mass, C, FFM, and D, FM at baseline and at each weekly clinic visit during RT.

Discussion

BIA measures of body composition were very strongly correlated with CT-based estimates, and BIA could discriminate sarcopenia among male patients with a sensitivity and specificity >90%. The close associations between BIA and CT were observed despite methodology that did not control for variations in eating, drinking, or exercising prior to BIA. Given the difficulties in maintaining nutrition exhibited by many head and neck cancer patients, we felt it is important to derive meaningful results without the need for fasting or other metabolic challenges. BIA was easy to perform and was readily integrated into a busy radiation oncology clinic; in our study weekly BIA was performed by registered dieticians and took fewer than 5 minutes per visit. In contrast to DXA, which is seldom available in radiation centers, or CT or MRI, which are expensive to perform and require dedicated post-analysis, BIA provided rapid results that were immediately interpretable. Given the plurality of studies reporting an association between depleted SM mass and shortened survival, interrogation of body composition can help clinicians with a priori risk stratification and may prove useful for patient stratification in future clinical trials, particularly those testing nutritional interventions or de-escalated therapy in patients with low-risk disease.

The association between BIA-determined sarcopenia and overall survival supports the utility of this instrument for identifying clinically meaningful decrements in skeletal muscle mass, although the low number of women included in the study limit the generalizability of these findings to female patients. The thresholds identified in this study fall within the range of “moderate sarcopenia”, identified by Janssen and colleagues as being associated with physical disability among older adults [27]. That normalized SM mass values in this range are associated with poor outcomes in both populations supports the interpretation that low muscle mass is a common indicator of underlying pathology. However, because head and neck cancers are increasingly common among younger patients, both age- and cancer-specific thresholds for sarcopenia may be necessary for clinical implementation.

Our results show no association between sarcopenia and other factors prognostic for survival, including HPV status, smoking history, age, and tumor stage. Sarcopenia was equally prevalent among patients with HPV-associated cancers, which often present with a small primary tumor and involved neck lymph nodes. That sarcopenia portends worse outcome among patients with HPV+ cancers adds to a growing literature suggesting that the association between sarcopenia and survival is independent of HPV status [1, 28–30]. As recently published retrospective data question this association, the prognostic value of sarcopenia among HPV-positive cancers, which are typically associated with improved survival should be the subject of future prospective analysis [4].

As a secondary outcome, we evaluated whether BIA was sensitive enough to monitor individual changes in body composition across treatment. BIA offers more information than body weight and may identify patients approaching the sarcopenia threshold. However, in this study the changes in FFM observed fell within the limits of agreement reported in the initial validation study performed on healthy individuals. A similar study in patients with colorectal cancer found that although single frequency BIA imprecisely measured changes in FFM, BIA could identify ≥ 5% in FFM with 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity [22]. Thus, BIA could potentially help stratify patients based on predefined thresholds in nutritional and supportive care trials investigating nutritional, exercise-based, and pharmacologic approaches to improving muscle mass, such as the ongoing investigation by the DAHANCA group [31].

Limitations

The low number of women participants precludes generalizability of our findings to female patients with head and neck cancer. Specific thresholds for BIA-determined sarcopenia need to be validated and refined in larger studies that include greater numbers of women patients. Evaluation of this technology in other cancer sites may demonstrate the need for cancer-specific and age-specific sarcopenia cut-offs. Our study also did not include post-RT imaging to validate the accuracy of post-treatment changes in body composition or the ability of BIA to identify new-onset sarcopenia.

Conclusions

In this prospective observational study, BIA was closely correlated with CT-derived measures of SM mass and FM. BIA demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for identifying male patients with sarcopenia, a negative prognostic factor in head and neck cancer. The use of BIA may be a practical solution for identifying patients with sarcopenia in routine clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

BIA- and CT-derived estimates of body composition are closely correlated

BIA identifies sarcopenia with sensitivity and specificity exceeding 90%

Sarcopenia defined by BIA portends poorer survival head and neck cancer

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Charles R. Thomas, MD, for his critical review of our final manuscript, and Yiyi Chen, PhD, for her review of the statistical methodology.

Study supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (1K08CA245188); National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248) and Academic-Industrial Partnership Award (1R01 DE028290-01); the National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Mathematical Sciences, Joint NIH/NSF Initiative on Quantitative Approaches to Biomedical Big Data (QuBBD) Grant (NSF 1557679); the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Early Stage Development of Technologies in Biomedical Computing, Informatics, and Big Data Science Award (1R01CA214825); the NCI Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148); the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Pilot Research Program Award from the UT MD Anderson CCSG Radiation Oncology and Cancer Imaging Program (P30CA016672); the NIH/NCI Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Developmental Research Program Award (P50 CA097007); and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) Research Education Program (R25EB025787). In-kind support provided by seca gmbh & co.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

AJG, CDR, JE, ASRM, DR, AC, PR, JP, GBG, SJF, WHM, ASG, CDF, and DIR declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Grossberg AJ, Chamchod S, Fuller CD, Mohamed AS, Heukelom J, Eichelberger H, et al. Association of Body Composition With Survival and Locoregional Control of Radiotherapy-Treated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:782–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chargi N, Bril SI, Emmelot-Vonk MH, de Bree R. Sarcopenia is a prognostic factor for overall survival in elderly patients with head-and-neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:1475–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jung AR, Roh JL, Kim JS, Kim SB, Choi SH, Nam SY, et al. Prognostic value of body composition on recurrence and survival of advanced-stage head and neck cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ganju RG, Morse R, Hoover A, TenNapel M, Lominska CE. The impact of sarcopenia on tolerance of radiation and outcome in patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2019;137:117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sealy MJ, Dechaphunkul T, van der Schans CP, Krijnen WP, Roodenburg JLN, Walker J, et al. Low muscle mass is associated with early termination of chemotherapy related to toxicity in patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Nutr. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zwart AT, van der Hoorn A, van Ooijen PMA, Steenbakkers R, de Bock GH, Halmos GB. CT-measured skeletal muscle mass used to assess frailty in patients with head and neck cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chamchod S, Fuller CD, Mohamed AS, Grossberg A, Messer JA, Heukelom J, et al. Quantitative body mass characterization before and after head and neck cancer radiotherapy: A challenge of height-weight formulae using computed tomography measurement. Oral Oncol. 2016;61:62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, Gallagher D, St-Onge MP, Albu J, et al. Visceral adipose tissue: relations between single-slice areas and total volume. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mourtzakis M, Prado CM, Lieffers JR, Reiman T, McCargar LJ, Baracos VE. A practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33:997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, Gallagher D, St-Onge MP, Albu J, et al. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004;97:2333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Baracos V, Caserotti P, Earthman CP, Fields D, Gallagher D, Hall KD, et al. Advances in the science and application of body composition measurement. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:96–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gómez JM, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis--part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:1226–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Haverkort EB, Reijven PL, Binnekade JM, de van der Schueren MA, Earthman CP, Gouma DJ, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis to estimate body composition in surgical and oncological patients: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bosy-Westphal A, Schautz B, Later W, Kehayias JJ, Gallagher D, Muller MJ. What makes a BIA equation unique? Validity of eight-electrode multifrequency BIA to estimate body composition in a healthy adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67 Suppl 1:S14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Axelsson L, Silander E, Bosaeus I, Hammerlid E. Bioelectrical phase angle at diagnosis as a prognostic factor for survival in advanced head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:2379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Büntzel J, Krauß T, Büntzel H, Küttner K, Fröhlich D, Oehler W, et al. Nutritional parameters for patients with head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2119–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Büntzel J, Micke O, Kisters K, Büntzel J, Mücke R. Malnutrition and Survival - Bioimpedance Data in Head Neck Cancer Patients. In Vivo. 2019;33:979–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lundberg M, Dickinson A, Nikander P, Orell H, Mäkitie A. Low-phase angle in body composition measurements correlates with prolonged hospital stay in head and neck cancer patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019;139:383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Małecka-Massalska T, Mlak R, Smoleń A, Brzozowska A, Surtel W, Morshed K. Capacitance of Membrane As a Prognostic Indicator of Survival in Head and Neck Cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Władysiuk MS, Mlak R, Morshed K, Surtel W, Brzozowska A, Małecka-Massalska T. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle as a prognostic indicator of survival in head-and-neck cancer. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:e481–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jager-Wittenaar H, Dijkstra PU, Earthman CP, Krijnen WP, Langendijk JA, van der Laan BF, et al. Validity of bioelectrical impedance analysis to assess fat-free mass in patients with head and neck cancer: an exploratory study. Head Neck. 2014;36:585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ræder H, Kværner AS, Henriksen C, Florholmen G, Henriksen HB, Bøhn SK, et al. Validity of bioelectrical impedance analysis in estimation of fat-free mass in colorectal cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, Reiman T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lyons W, Gallagher D, Ross R. Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;85:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:629–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Parsons HA, Baracos VE, Dhillon N, Hong DS, Kurzrock R. Body composition, symptoms, and survival in advanced cancer patients referred to a phase I service. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Janssen I, Baumgartner RN, Ross R, Rosenberg IH, Roubenoff R. Skeletal muscle cutpoints associated with elevated physical disability risk in older men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stone L, Olson B, Mowery A, Krasnow S, Jiang A, Li R, et al. Association Between Sarcopenia and Mortality in Patients Undergoing Surgical Excision of Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145:647–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chargi N, Bril SI, Swartz JE, Wegner I, Willems SM, de Bree R. Skeletal muscle mass is an imaging biomarker for decreased survival in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2020;101:104519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tamaki A, Manzoor NF, Babajanian E, Ascha M, Rezaee R, Zender CA. Clinical Significance of Sarcopenia among Patients with Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:480–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lonkvist CK, Lonbro S, Vinther A, Zerahn B, Rosenbom E, Primdahl H, et al. Progressive resistance training in head and neck cancer patients during concomitant chemoradiotherapy -- design of the DAHANCA 31 randomized trial. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.