Abstract

Objectives:

This study sought to assess whether poor sleep is associated with aspects of executive function (EF) among children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), or typical development (TD), after adjusting for demographic variables, stimulant medications, intelligence, anxiety, inattention, and hyperactivity.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Children recruited through ongoing studies at the Kennedy Krieger Institute.

Participants:

We studied 735 children (323 TD; 177 ASD; 235 ADHD) aged 8-12 years.

Measurements:

We investigated associations of parent-reported sleep measures from the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) with parent-report measures of EF and performance-based processing speed with each clinical population. EF was measured using 8 clinical T scores that fall under two domains (behavioral regulation and metacognition) from the Behavior Rating Inventory of EF (BRIEF) and the processing speed index from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV or -V.

Results:

Higher CSHQ scores were associated with poorer EF on all BRIEF scales, across all child groups, after adjustment for demographic factors, stimulant medications, and IQ. Among children with ADHD, these associations largely remained after adjusting for anxiety. Among those ASD, anxiety partially accounted for these associations, especially for behavioral regulation EF outcomes. Co-occurring symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity further accounted for the associations between sleep and EF. Poor sleep was not significantly associated with processing speed.

Conclusions:

Strong links exist between parent-reported poor sleep and executive dysfunction in children with typical development. Targeting anxiety may alleviate executive dysfunction, especially among children with ASD.

Keywords: Sleep, ADHD (attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder), ASD (autism spectrum disorder), Executive Function

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are among the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood. ASD is defined by social deficits and patterns of stereotyped and repetitive behavior, while ADHD is characterized by difficulties with attentiveness and/or activity regulation.1 Current prevalence estimates indicate that nearly 2% of school-aged children have an ASD.2 ADHD is even more common, affecting 8-10% of school age children.3 While first diagnosed in childhood, both ASD and ADHD can persist into adolescence and adulthood, contributing to impairments in academic, occupational, and social/interpersonal functioning as well as poor functional outcomes.4 Notably, at least half of children with ASD may also meet criteria for ADHD.5 Conversely, recent data suggests that about 12-13% of children with ADHD also have ASD.6 Accumulating evidence suggests that when ASD and ADHD symptoms co-occur there is a negative impact on long-term behavioral development,7 attentional performance,8 and adaptive behavior.9,10

Sleep-related problems are common in children with ASD and in those with ADHD. Among children and adolescents with ASD, 50-80% have sleep problems in contrast to 9-50% of the general population.11 Similarly, between 25% and 55% of children with ADHD have sleep problems according to their parents,12 and nearly 20% experience moderate to severe sleep problems at least once a week.13 For both disorders, these issues are characterized by greater latencies to sleep onset,14 night-time wakefulness,11,14 shorter sleep duration,15,16 greater daytime sleepiness,15,16 bedtime resistance,15,17 and early awakenings,15,18 relative to typically developing (TD) children.

Sleep disturbance in childhood and adolescence can have significant detrimental effects on cognition and various domains of behavior.19 Executive function represents one such construct and is also impaired in both ASD and ADHD.20 Executive functions are commonly considered mental control processes, largely supported by the prefrontal cortex, that permit self-control, problem-solving, and include a number of cognitive domains such as response inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility (e.g., in set-shifting).21

In children generally, sleep loss hinders executive control, including completion of complex tasks, creativity, integration, planning, supervisory control, problem solving, divergent thinking capacity and working memory;22 and poor sleep has been associated with impaired performance on tasks requiring higher attention or executive control, including a continuous performance task of sustained visual attention and a symbol-digit substitution task.23

A number of studies have also examined the association between poor sleep and executive function in children with ASD or ADHD.24-26 Among children with ASD, sleep disturbances, such as trouble falling and staying asleep, short and long sleep duration, and restless sleep, have been linked to poor working memory.25 In studies of children with ADHD, parent-reported total sleep disturbance (CSHQ total score) has been associated with deficits in executive function control skills.24

The link between poor sleep and executive function within these diagnostic groups is complex and may be accounted for by a number of factors. For example, stimulant medications, which influence executive function27 and are frequently prescribed to children with ASD or ADHD, may contribute to insomnia.28 Anxiety is quite common among individuals with ASD or ADHD, is closely linked to sleep,28 and influences cognitive function.29-30 Lastly, children with ASD often also have symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, regardless of whether they actually have a co-occurring diagnosis of ADHD, and these symptoms are closely tied to sleep and cognitive and behavioral outcomes as well.24,26,28

To our knowledge, however, no study has yet examined whether the association between sleep and executive function remains after adjusting for all these factors. To address these gaps, we measured parent-reported sleep disturbance in a large pediatric cohort (n = 735) of children with ASD, ADHD, or TD, investigated its association with quantitative measures of executive function, and assessed the degree to which covariates, including anxiety and symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity, account for this association. We hypothesized that associations between poor sleep and executive function would remain after adjusting for demographic variables, but would be largely accounted for by symptoms of anxiety, inattention, and hyperactivity.

Participants and Methods

Participants

Children aged 8-12 years old were recruited through ongoing studies at the Center for Neurodevelopmental and Imaging Research (CNIR) at the Kennedy Krieger Institute (KKI) (n=736). We restricted our sample to children with complete data on the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ).33 Only 1 individual was dropped due to missing any data on the CSHQ. Our analytic sample (n=735) consisted of 323 TD children, 177 children with ASD, and 235 children with ADHD.

Participants were recruited through community resources including local chapters of the Autism Society of America, local public and private schools, clinics at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, volunteer organizations, medical institutions, and word of mouth. These studies were approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Interested parents were provided with a description of the study, after which they signed informed consent and children provided verbal assent. Participants were initially screened via parent telephone interview to determine eligibility (details below). After enrollment, participants attended two laboratory sessions (from 8:30-1:30 with a 1-hour lunch break at noon) during which they completed a neuropsychological assessment battery. Parents completed behavior rating scales, including the measures of executive function employed in this analysis, outside of the laboratory and at their own leisure.

Diagnostic and Exclusion procedures

ASD Diagnosis

Diagnosis of ASD was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth or Fifth Edition (DSM-IV or −5) criteria34 and confirmed using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)35 or Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2)36 and the clinical impression of a board-certified child neurologist (senior author SHM) with extensive experience with ASD. Children with histories of known etiology for ASD (e.g., fragile X syndrome) were excluded.

ADHD Diagnosis

Diagnosis of ADHD was based on DSM-IV or −5 criteria and confirmed using a structured parent interview, either the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-IV (DICA-IV)37 or the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS)38 as well as parent and teachers versions of a rating scale, either the Conners-Revised39 or Conners-340 Rating Scale and confirmed by a board-certified child neurologist with extensive experience with ADHD (SHM). Children who met criteria for both ADHD and ASD were classified as having ASD for the purposes of this analysis.

Exclusion Criteria from Parent Studies

This sample is derived from existing NIH- and foundation-funded parent studies that focused on examining brain-behavior relationships underlying sensory, motor, and cognitive dysfunction. Children with ASD and ADHD were recruited separately. Children were excluded from the parent studies if they had histories of neurologic illness or injury, genetic disorders, seizures, or intellectual disability. Children in all groups with a full-scale IQ (FSIQ) <8041,42 on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC)–IV or WISC-V were excluded unless there was a 12 point or greater index discrepancy between subscale scores,43 in which case either the Verbal Comprehension Index or Perceptual Reasoning Index was required to be > 80 and the lower of the two was required to be > 65.44 Children were also administered the Word Reading subtest from the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition WIAT-II45 to screen for a reading disorder and were excluded in the case of a significant discrepancy between FSIQ and WIAT-II. Children were included in the TD control group if they did not meet published cutoff criteria for ASD on the parent-report Social Responsiveness Scale, did not have a history of ADHD, developmental or psychiatric disorder, based on maternal and child responses assessed on the K-SADS,38 Conners Parent Rating Scales,39,40 and DuPaul ADHD Rating Scale46, and were free of immediate family members (sibling, parent) with ASD, as reported by the parent.

The WISC-IV FSIQ was calculated from the following ten subtests: three verbal comprehension (Vocabulary, Similarities, and Comprehension), three perceptual reasoning (Block Design, Picture Concepts, and Matrix Reasoning), two working memory (Digit Span and Letter-Number Sequencing), and two processing speed (Coding and Symbol Search).47 The WISC-V FSIQ was calculated from the following seven subtests: two verbal comprehension (Vocabulary, Similarities), one visual spatial (Block Design), two fluid reasoning (Matrix Reasoning, Figure Weights), one working memory (Digit Span), and one processing speed (Coding).48

Children meeting criteria for active psychosis, major depression, bipolar disorder, conduct disorder, or adjustment disorder, based on the DICA-IV or the K-SADS, were excluded from the parent studies. Children with ADHD or TD with comorbid anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, simple and social phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), were excluded. For children with ASD, comorbid anxiety disorders were allowed to participate, given that anxiety is common in ASD and repetitive repertoires resembling obsessive-compulsive behavior are components of the diagnostic criteria for ASD. None of the children with TD were taking psychotropic medications. Children with ADHD taking non-stimulant medications, SSRIs, or other psychotropic medications were excluded. Children with ASD or ADHD taking stimulant medications were asked to withhold their medication the day of and the day prior to study participation, to avoid effects on cognitive and behavioral measures. Children with ASD taking other psychotropic medications were allowed to participate and were allowed to continue these medications that would normally require a longer washout period, for both ethical and practical reasons. Medication information was provided by the parents and reported on a Developmental and Medical History Form completed at the time of enrollment. The medications classified as stimulants included Dextroamphetamine, Methylphenidate, Dexmethylphenidate, Lisdexamfetamine, and Quillivant, including any long-acting, extended, or sustained-release forms of these medications.

Measures

Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire

Parent-report of sleep problems was collected at recruitment using the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), a 33-item scale that queries about common clinically reported pediatric sleep problems (bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, shorter sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), and daytime sleepiness).33 Each item has a 3-point scale to specify the frequency of the sleep problem: “usually” (i.e., 5–7 times within the past week), “sometimes” (i.e., 2–4 times within the past week), or “rarely” (i.e., never or 1 time within the past week). The CSHQ is scored as a continuous measure, with a total score and 8 subscale scores, calculated from its 33 items, with higher scores indicating more disturbed sleep. Individuals can also be classified according to whether or not they met clinical levels of sleep disturbance (total score ≥41)33 Individual items, subscales, and total score all demonstrate good validity in a school-age typically developing population.33

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were the clinical T scores from the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF).49 The BRIEF scores are represented by two domains or indices: the behavioral regulation and metacognition indices. In addition, a global executive composite score can be calculated, which was summarized in this paper for descriptive purposes but not included as an outcome in regression analyses. The ‘behavioral regulation’ index consists of the Inhibit, Shift, and Emotional Control clinical T scores. The ‘metacognition’ index consists of the Initiate, Working Memory, Planning/Organization, Organization of Materials and Monitor clinical T scores. Additionally, we included the processing speed index (PSI) from the WISC-IV or -V (depending which was administered) as a performance-based measure of executive function which represents the speed of cognitive processes and response output.50

Covariates

In addition to the measures described above, participants provided demographic data, including age, gender, race (White; African-American; Asian; Biracial), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino; non-Hispanic/Latino), and Hollingshead51 Index family socioeconomic status (SES) score. The General Ability Index (GAI) from the WISC IV or WISC V was used as an overall measure of intellectual ability. The Anxiety Problems T score from the Child Behavior Checklist,52 and the Inattentive and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity Scale T scores from the parent-report version of either the Conners-R39 (46%) or Conners-340 (54%) were also included as covariates. The CBCL Anxiety Problems T score is a DSM-V-oriented scale predictive of generalized anxiety disorder, separation disorder, and specific phobia, and demonstrates strong reliability and convergent and discriminative validity.52 The Conners-R and Conners-3 Parent Rating Scales are designed to assess ADHD and common co-occurring problems in children 6-18 years old, based on the parent’s observation of their child’s behavior. Groups of items on the Conners comprise various content scales or domains of behavior, such as inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scales.39,40

Imputation

Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to impute missing data. Missingness was infrequent (<5%) across all variables, except for the CBCL Anxiety Problems T score (16% missing) and race (13% missing). Fifty imputations were performed, with 50 iterations per imputation. Predictive mean matching and polytomous logistic regression were used for continuous and categorical covariates, respectively, using the R package “mice” (version 3.8.0).53

Analytic Procedures

We summarized the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample across diagnostic groups using the mean (standard deviation) or frequency and percentage. We calculated ANOVA and Chi-square tests to assess whether these characteristics differed statistically by diagnosis. The estimated marginal means of the sleep predictors were calculated, adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, SES, use of stimulant medications, CBCL Anxiety Problems T score, and GAI. Next, we fit a series of multivariable linear regression models to estimate the associations between the sleep predictor (continuous CSHQ total score) and the EF outcomes. We ran this analysis within three diagnostic groups: children with TD, ASD, and ADHD.

We ran models first adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, SES, use of stimulant medications, and GAI (“Model 1”). Next, we adjusted for the CBCL Anxiety Problems T score in addition to Model 1 covariates (“Model 2”). Lastly, in Model 3, we further adjusted for Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity scores in addition to the Model 2 covariates. In models of individuals with TD, we did not adjust for stimulant medications because no participants were taking any.

Results

Participants were approximately 10 years old on average (range 8-12 years), mostly male, and mostly White, non-Hispanic (Table 1). Children with ASD were significantly more likely to be boys relative to children with TD or ADHD (both p<0.01). As expected, children with TD showed lower severity on the Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores, BASC Anxiety T score, and all BRIEF scores (all p<0.0001). Children with ADHD had higher Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores compared to children with ASD (p<0.0001), whereas children with ASD had higher CBCL Anxiety Problems T scores than children with ADHD or TD (p<0.0001). Among children with ASD, 66% also met criteria for ADHD (Table 1). There were no significant differences in hyperactive/impulsive or inattentive ADHD subtypes between children with ASD and ADHD, though there were significantly more children with ADHD that had the combined subtype (73.2% vs 40.1%, p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Diagnostic Group

| TD (n=323) |

ASD (n=177) | ADHD (n=235) |

P-value ANOVA/Chi- square Test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | ||||

| Age (years) | 10.2 (1.2) | 10.1 (1.4) | 9.9 (1.3) | p=0.03 |

| Male | 71.0% | 86.4% | 72.2% | p<0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 60.1% | 80.0% | 68.7% | p=0.01 |

| African-American | 10.0% | 9.3% | 15.5% | |

| Asian | 0.1% | 1.7 | 4.3% | |

| Biracial | 12.8% | 9.3% | 11.6% | |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | 6.2% | 10.9% | 11.5% | p=0.06 |

| Family SES | 54.6 (8.8) | 51.2 (9.5) | 51.4 (10.6) | p<0.0001 |

| Conners Inattention T | 45.3 (6.1) | 70.1 (12.3) | 74.9 (10.1) | p<0.0001 |

| Conners Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T | 46.8 (6.1) | 69.7 (13.2) | 73.9 (13.1) | p<0.0001 |

| GAI | 116.2 (12.3) | 105.1 (16.6) | 109.4 (12.9) | p<0.0001 |

| CBCL Anxiety Problems T | 52.2 (4.2) | 63.1 (9.1) | 58.1 (7.9) | p<0.0001 |

| Psychotropic Medications | ||||

| Stimulant | 0% | 37.9% | 58.3% | p<0.0001 |

| SSRI | 0% | 11.9% | 0% | p<0.0001 |

| Non-stimulant | 0% | 9.0% | 0% | p<0.0001 |

| Other | 0% | 8.5% | 0% | p<0.0001 |

| ADHD Diagnosis | 0% | 66% | 100% | --- |

| ADHD Subtype | ||||

| Combined | 0% | 40.1% | 73.2% | p<0.0001 |

| Hyper/Impulsive | 0% | 2.8% | 0.9% | |

| Inattentive | 0% | 23.2% | 25.5% |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of analytic sample, stratified by diagnostic group (TD, ASD, ADHD). Mean (SD) or % are shown for each variable. P-values for ANOVA/Chi-square tests for differences across the four diagnostic group are shown. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; T: T score; GAI: general ability index; CBCL: child behavior checklist; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

The BRIEF behavioral regulation index was notably elevated in children with ASD (67.1) relative to children with ADHD (62.1) and TD (42.4) (both p<0.0001), while the BRIEF metacognition index was similar (p=0.39) in children with ASD (67.5) and ADHD (68.2) but lower in children with TD (43.0) (p<0.0001) (Table 2). The WISC PSI score was lowest in the ASD group (88.5), highest in the TD group (103.7) with an intermediate score for the ADHD group (95.1) (all pairwise p<0.0001).

Table 2.

BRIEF Clinical Scale and Index T scores and WISC PSI score by Diagnostic Group

| TD (n=323) |

ASD (n=177) |

ADHD (n=235) |

P-value ANOVA/Ch i-square Test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | ||||

| BRIEF Inhibit | 44.0 (6.1) | 64.1 (11.8) | 65.4 (11.7) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Shift | 43.3 (6.9) | 70.0 (12.0) | 57.5 (11.9) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Emotional Control | 42.9 (6.6) | 61.6 (11.5) | 57.8 (12.2) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Initiate | 44.8 (7.1) | 64.2 (10.6) | 62.8 (9.3) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Working Memory | 44.2 (6.8) | 67.4 (9.7) | 70.2 (7.8) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Planning/Organization | 43.0 (7.1) | 66.2 (10.6) | 66.1 (9.2) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Organization of Materials | 47.3 (8.7) | 59.4 (10.0) | 62.7 (7.8) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Monitor | 41.9 (8.3) | 65.7 (10.2) | 63.7 (9.2) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Behavioral Regulation Index | 42.4 (6.0) | 67.1 (11.1) | 62.1 (11.3) | p<0.0001 |

| BRIEF Metacognition Index | 43.0 (7.2) | 67.5 (10.0) | 68.2 (7.8) | p<0.0001 |

| Brief Global Executive Composite | 42.3 (6.5) | 68.7 (9.7) | 67.0 (8.5) | p<0.0001 |

| WISC PSI | 103.7 (13.3) | 88.5 (16.9) | 95.1 (12.2) | p<0.0001 |

Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions; WISC PSI: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Processing Speed Index

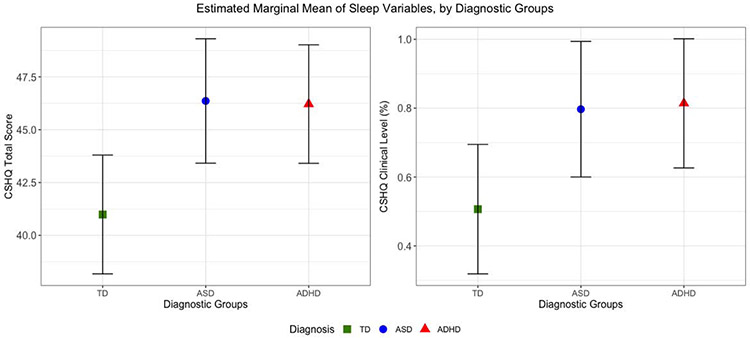

As depicted in Figure 1 and Table 3, children with ASD or ADHD showed higher CSHQ total scores on average and were more likely to reach a clinical level of sleep problems, after adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, SES, stimulant medication, GAI, and anxiety. On all CSHQ scales, with the exception of SDB, children with ASD or ADHD had significantly elevated levels of sleep disturbances compared to children with TD (Table 3). Children with ASD and ADHD did not have significantly different CSHQ scores from each other, with the exception of night wakings which were slightly but significantly elevated in the ASD group (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Adjusted Estimated Marginal Mean of Sleep Predictors across Diagnostic Groups.

Adjusted estimated marginal mean of sleep predictors (CSHQ Total Score and CSHQ Clinical Level) across diagnostic groups, adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, SES, use of stimulant medications, and general ability index. Bars around point estimate represent confidence interval for the marginal mean estimate. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; CSHQ: Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Sleep Measures by Diagnostic Group – Unadjusted & Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race, Ethnicity, SES, Stimulant Medication, and General Ability Index.*

| Unadj | Adj | Unadj | Adj | Unadj | Adj | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD (n=323) | ASD(n=177) | ADHD (n=235) | ||||

| CSHQ Total#§ | 39.4 | 41.0 | 46.0 | 46.4 | 46.3 | 46.2 |

| CSHQ Bedtime Resistance #§ | 6.8 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 8.3 |

| CSHQ Sleep Onset Delay #§ | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| CSHQ Sleep Duration #§ | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.6 |

| CSHQ Sleep Anxiety #§ | 4.7 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| CSHQ Night Wakings #§* | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| CSHQ Parasomnias #§ | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.7 |

| CSHQ Sleep-Disordered Breathing | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| CSHQ Daytime Sleepiness #§ | 10.9 | 11.2 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 13.3 | 13.2 |

| CSHQ Clinical Level #§ | 27% | 51% | 62% | 80% | 67% | 81% |

denotes measure was significantly higher (p<.05) in the ASD group, relative to TD.

denotes measure was significantly higher (p<.05) in the ADHD group, relative to TD.

denotes measure was significantly higher (p<.05) in the ASD group, relative to ADHD.

Associations between Sleep Disturbance and Executive Function

Behavioral Regulation Clinical Scores

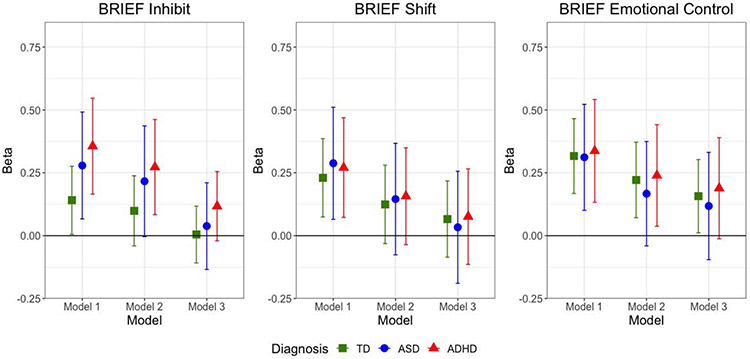

CSHQ total score was significantly associated with the BRIEF Inhibit score among children with TD, ASD, and ADHD in Model 1, which adjusted for demographic variables, use of stimulant medications, and GAI (Table 4, Figure 2). After further adjustment for anxiety (Model 2), the associations were slightly attenuated in all groups and no longer statistically significant among children with TD and ASD. After incremental adjustment for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Model 3), the association across all three child groups became null.

Table 4.

Regression Output: CSHQ Total Score as Predictor of BRIEF Clinical Scales

| Group | Model 1 Beta (95% CI) |

Model 2 Beta (95% CI) |

Model 3 Beta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: BRIEF Inhibit Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.14 (0.01, 0.28)* | 0.1 (−0.04, 0.24) | 0 (−0.11, 0.12) |

| ASD | 0.28 (0.07, 0.49)* | 0.22 (0, 0.44) | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.21) |

| ADHD | 0.36 (0.17, 0.55)* | 0.27 (0.08, 0.46)* | 0.12 (−0.02, 0.25) |

| Outcome: BRIEF Shift Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.23 (0.07, 0.39)* | 0.12 (−0.03, 0.28) | 0.07 (−0.09, 0.22) |

| ASD | 0.29 (0.06, 0.51)* | 0.15 (−0.08, 0.37) | 0.03 (−0.19, 0.26) |

| ADHD | 0.27 (0.07, 0.47)* | 0.16 (−0.04, 0.35) | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.27) |

| Outcome: BRIEF Emotional Control Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.32 (0.17, 0.47)* | 0.22 (0.07, 0.37)* | 0.16 (0.01, 0.3)* |

| ASD | 0.31 (0.1, 0.52)* | 0.17 (−0.04, 0.37) | 0.12 (−0.1, 0.33) |

| ADHD | 0.34 (0.13, 0.54)* | 0.24 (0.04, 0.44)* | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.39) |

| Outcome: BRIEF Initiate Control Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.4 (0.24, 0.55)* | 0.36 (0.2, 0.52)* | 0.24 (0.1, 0.37)* |

| ASD | 0.28 (0.09, 0.48)* | 0.23 (0.03, 0.44)* | 0.06 (−0.12, 0.23) |

| ADHD | 0.3 (0.15, 0.45)* | 0.24 (0.09, 0.39)* | 0.18 (0.02, 0.33)* |

| Outcome: BRIEF Working Memory Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.32 (0.17, 0.47)* | 0.31 (0.15, 0.46)* | 0.15 (0.03, 0.28)* |

| ASD | 0.34 (0.18, 0.51)* | 0.3 (0.13, 0.47)* | 0.09 (−0.04, 0.23) |

| ADHD | 0.29 (0.16, 0.42)* | 0.27 (0.14, 0.4)* | 0.17 (0.05, 0.29)* |

| Outcome: BRIEF Planning/Organization Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.34 (0.19, 0.50)* | 0.31 (0.16, 0.47)* | 0.18 (0.04, 0.31)* |

| ASD | 0.40 (0.22, 0.58)* | 0.35 (0.16, 0.53)* | 0.13 (−0.02, 0.29) |

| ADHD | 0.27 (0.11, 0.42)* | 0.24 (0.08, 0.4)* | 0.14 (−0.01, 0.28) |

| Outcome: BRIEF Organization of Materials Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.53 (0.34, 0.71)* | 0.49 (0.31, 0.68)* | 0.38 (0.2, 0.56)* |

| ASD | 0.31 (0.13, 0.5)* | 0.3 (0.11, 0.49)* | 0.11 (−0.06, 0.28) |

| ADHD | 0.17 (0.04, 0.3)* | 0.16 (0.03, 0.29)* | 0.07 (−0.06, 0.2) |

| Outcome: BRIEF Monitor Clinical T Score | |||

| TD | 0.37 (0.19, 0.55)* | 0.32 (0.14, 0.51)* | 0.19 (0.03, 0.35)* |

| ASD | 0.29 (0.11, 0.47)* | 0.26 (0.07, 0.45)* | 0.1 (−0.08, 0.27) |

| ADHD | 0.17 (0.02, 0.33)* | 0.14 (−0.02, 0.3) | 0.05 (−0.11, 0.2) |

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, family SES, use of stimulant meds, and GAI. Model 2 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus CBCL Anxiety Problems T score. Model 3 adjusts for Model 2 covariates plus Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores. Models within TD group did not adjust for stimulant meds. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

p<0.05

Figure 2. Multivariable Linear Regression Results: Child Sleep Health Questionnaire (CSHQ) Total Score as Predictor of BRIEF T Scores from Behavioral Regulation Clinical Scales, by Diagnosis.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, family SES, use of stimulant meds, and GAI. Model 2 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus CBCL Anxiety Problems T score. Model 3 adjusts for Model 2 covariates plus Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores. Models within TD group did not adjust for stimulant meds. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions; CSHQ: Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Y axis represents unstandardized regression coefficient (Beta).

CSHQ total score was significantly associated with the BRIEF Shift score among children with TD, ASD, and ADHD in Model 1. After adjusting for anxiety (Model 2), the association attenuated and was no longer significant in any of the groups. The associations moved even closer to the null after adjusting for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Model 3).

CSHQ total score was significantly associated with the BRIEF Emotional Control score among children with TD, ASD, and ADHD in Model 1. After adjusting for anxiety (Model 2), the association remained significant among children with TD and ADHD, but not among children with ASD. Model 3 further attenuated the results, rendering the association only significant among children with TD.

BRIEF Metacognition Clinical Scores

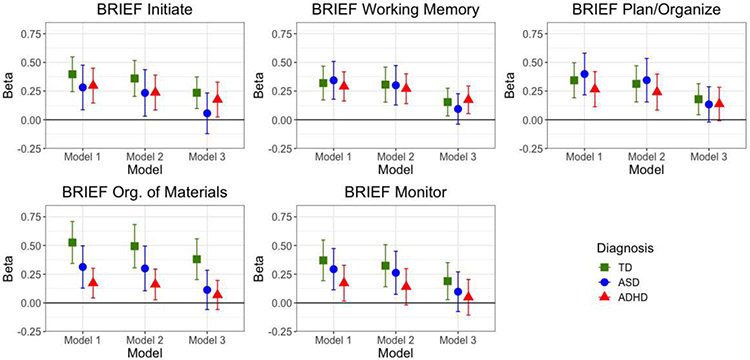

Across all five BRIEF ‘metacognition’ scales (Initiate, Working Memory, Planning/Organization, Organization of Materials, Monitor), CSHQ total score was significantly associated with the BRIEF clinical scores among all three groups of children in both Model 1. Adjusting for anxiety attenuated these associations though they all remained significant, with the exception of the BRIEF monitor outcome among the ADHD group. For all five scales, adjusting for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity among children with ASD (Model 3) shifted the estimate substantially closer to the null and rendered the association nonsignificant. The associations were reduced across all scales among the ADHD group, though significant associations remained for the Initiate and Working Memory scores. CSHQ total score remained significantly associated with all five scales even after adjustment in Model 3. Estimates are shown in Table 4 and visually depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Multivariable Linear Regression Results: Child Sleep Health Questionnaire (CSHQ) Total Score as Predictor of BRIEF T Scores from Metacognition Clinical Scales, by Diagnosis.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, family SES, use of stimulant meds, and GAI. Model 2 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus CBCL Anxiety Problems T score. Model 3 adjusts for Model 2 covariates plus Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores. Models within TD group did not adjust for stimulant meds. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder;; BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions; CSHQ: Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Y axis represents unstandardized regression coefficient (Beta).

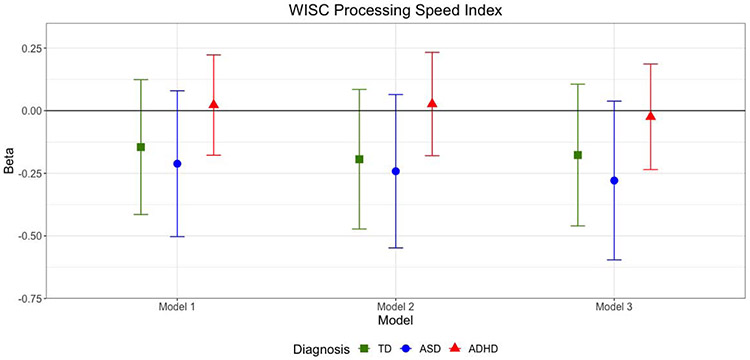

WISC Processing Speed Index

There was a negative, but not significant, association between CHSQ total score and WISC PSI among children with TD and ASD across all three models (i.e., greater sleep problems were associated with worse performance on the WISC PSI). The association between CSHQ total score and WISC PSI was null across all models in the ADHD group (Table 5 and Figure 4).

Table 5.

Regression Output: CSHQ Total Score as Predictor of WISC Processing Speed Index

| Group | Model 1 Beta (95% CI) |

Model 2 Beta (95% CI) |

Model 3 Beta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: WISC PSI | |||

| TD | −0.15 (−0.41, 0.12) | −0.19 (−0.47, 0.08) | −0.18 (−0.46, 0.11) |

| ASD | −0.21 (−0.5, 0.08) | −0.24 (−0.55, 0.06) | −0.28 (−0.6, 0.04) |

| ADHD | 0.02 (−0.18, 0.22) | 0.03 (−0.18, 0.23) | −0.02 (−0.24, 0.19) |

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, family SES, use of stimulant meds, and GAI. Model 2 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus CBCL Anxiety Problems T score. Model 3 adjusts for Model 2 covariates plus Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores. Models within TD group did not adjust for stimulant meds. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. *p<0.05

Figure 4. Multivariable Linear Regression Results: Child Sleep Health Questionnaire (CSHQ) Total Score as Predictor of WISC Processing Speed Index, by Diagnosis.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, family SES, use of stimulant meds, and GAI. Model 2 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus CBCL Anxiety Problems T score. Model 3 adjusts for Model 2 covariates plus Conners Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity T scores. Models within TD group did not adjust for stimulant meds. Abbreviations are TD - typically developing; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; WISC: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, versions 4 and 5; CSHQ: Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Y axis represents unstandardized regression coefficient (Beta).

Discussion

A primary goal of this paper was to estimate the association between poor sleep and executive dysfunction across children with TD, ASD, or ADHD, and determine whether demographic variables, stimulant medication use, GAI, anxiety, and symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity accounted for these associations. In general, we found poorer sleep was significantly associated with lower executive function as measured by parent report among all groups of children when accounting for demographic variables, stimulant medication, and intelligence (GAI). Our findings are consistent with existing literature revealing sleep disturbances is associated with deficits in executive dysfunction in TD children,22 children with ASD,25 and children with ADHD.24

Our study furthered this literature by showing that, among children with ADHD, the associations between sleep and behavioral regulation components of executive function partially remained after accounting for anxiety, but were largely rendered not significant after adjusting for symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. The exceptions to this were that poor sleep remained a significant predictor of the initiate and working memory scores among children with ADHD, even after adjustment for anxiety and ADHD symptoms. Assuming no residual confounding, this suggests that poor sleep remains an important target for interventions aimed at improving executive function among children with ADHD.

In contrast, for children with ASD, the associations between sleep and Shift and Emotional Control scores were largely accounted for by anxiety, although the association between poor sleep and the Inhibit clinical score remained after adjusting for anxiety. In terms of the metacognition scores, adjusting for anxiety generally did not account for the association among children with ASD or ADHD. However, adjusting for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity led to fully null associations among children with ASD, and attenuated or null associations among children with ADHD.

Contrary to what we expected, the total CSHQ score was not significantly associated with performance-based processing speed in any of the models among any of the child groups. While we may have been underpowered to detect a significant association, the null findings, especially among the ADHD group, suggests that parent-report of child’s sleep may be more tightly linked with parent-report measures of executive function, perhaps because the parent’s own response to the child’s poor sleep affects their interpretation of the child’s executive function. Yet, parent-report measures of executive function and other cognitive or behavioral constructs have ecological validity even when they are not strongly associated with objective performance.54,55

Together, these findings emphasize the need for future studies to assess whether, among children with ADHD, the effects of sleep dysfunction on executive function seem largely intrinsic to the core symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. In contrast, among children with ASD, minimizing the negative impact of sleep dysfunction on cognitive flexibility, emotional control and other behavioral aspects of executive function, may require directly addressing anxiety. It is possible that anxiety was a stronger driver of these outcomes among children with ASD because those with co-occurring anxiety were allowed to participate, whereas clinically-significant anxiety was excluded from the ADHD and TD groups. In other words, this finding may be a function of the greater variability in anxiety symptoms in the ASD group. However, this does still suggest that in a sample of children with ASD, anxiety plays an important role in the link between sleep and executive function, whereas the association between sleep and executive function among children with ADHD remains even after removing clinical anxiety and adjusting for anxiety symptoms. We note however that the sleep-anxiety link is still relevant to executive function in ADHD,24,56 but its importance is less in this particular study sample.

Targeting symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity among children with ASD may also help to address the negative impact of sleep dysfunction on both behavioral regulation and metacognition components of executive function. These, too, are questions in need of further study, especially in prospective or experimental designs.

On all CSHQ scales, with the exception of SDB, children with ASD or ADHD had significantly higher levels of sleep disturbance compared to TD children. These findings are generally consistent with the current literature revealing that various dimensions of sleep are disturbed in children with ASD, ADHD, or both, relative to TD children.11,13-16,57 Our finding that SDB was not significantly different across groups was not surprising. In studies of children with ASD or ADHD, reports of elevated SDB have been mixed, in part due to the difficulties of accurately measuring SDB in these.58-60

This study had a number of strengths. First, the sample size was relatively large, consisting of 735 total children, of which 177 had ASD and 235 had ADHD. We were able to adjust for several potential confounding or mediating variables, including demographic factors, stimulant medication, intelligence, anxiety, as well as symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, to show how these variables affected the association between sleep and executive function.

This study also had some limitations which prevents us from making causal statements about our findings. The CSHQ used in this study to assess for poor sleep depends on parent recognition of symptoms and signs in their child, which may not always be accurate or reliable, especially in children who are not typically developing, as these children may be less likely to report difficulties falling or staying asleep to their parents. For example, nocturnal awakenings may be underreported in children with ASD, which could bias our results. While the CSHQ has been demonstrated to have good validity in typically developing children,33 research suggests modifications to the tool are necessary for the ASD population,60,61 and we are not aware of any validation studies among children with ADHD. Next, we excluded children with histories of neurologic illness or injury, genetic disorders, seizures, intellectual disability, or major mental health disorders with the exception of anxiety disorders in children with ASD. While this is a strength of this study in terms of minimizing the potential confounds introduced by these conditions and associated medications, it also may reduce the generalizability of this findings. Our analytic sample also had a low proportion of children with the ‘hyperactive/impulsive’ ADHD subtype, which may limit generalizability. Further work needs to be conducted across different samples of children with ASD, ADHD, and TD to replicate. We also recognize that parents rated both the sleep and executive function measures in this study, so there may be shared variance between these factors due to the nature of parent-report methods. It is also possible that the medication cessation in the day prior to testing might have influenced the parent’s report of child executive function, behavior, and sleep, although we suspect that the average of these measurements in the past week would not be largely affected by the one day of cessation. In addition, we did not adjust for the number of statistical tests carried out given that the outcomes of interest were all related components of executive function. Therefore, it is possible that some of our findings were false positive results due to multiple testing. Finally, longitudinal studies will be crucial to addressing causal outcomes associated with poor sleep.

Nevertheless, given the salience of both sleep and cognition for overall health and well-being in children, the current findings provide important initial insights, particularly since prior research suggests that these associations may be bidirectional.62 In this paper we replicated the finding that children with ASD and ADHD have disturbed sleep relative to their typically developing peers. We were able to demonstrate strong links between poor sleep and executive dysfunction in children with typical development, ASD, and ADHD, and demonstrate that co-occurring symptoms of anxiety, inattention, and hyperactivity or impulsivity appear to account for the associations between sleep and executive function among children with ASD.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (5T32MH014592; R21MH098228; R01MH106564), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS048527), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Intellectual Developmental Disabilities Research Center (1P50HD103538-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

Financial disclosures:

Adam Spira received honoraria from Springer Nature Switzerland AG for Guest Editing Special Issues of Current Sleep Medicine Reports.

Non-financial disclosures: None

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maenner MJ. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U. Comorbidity prevalence, healthcare utilization, and expenditures of Medicaid enrolled adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2017;21(8):995–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens T, Peng L, Barnard-Brak L. The comorbidity of ADHD in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;31:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zablotsky B, Bramlett MD, Blumberg SJ. The co-occurrence of autism spectrum disorder in children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(1):94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerys BE, Bertollo JR, Pandey J, Guy L, Schultz RT. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms Are Associated With Lower Adaptive Behavior Skills in Children With Autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(5):525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dajani DR, Llabre MM, Nebel MB, Mostofsky SH, Uddin LQ. Heterogeneity of executive functions among comorbid neurodevelopmental disorders. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virring A, Lambek R, Jennum PJ, Møller LR, Thomsen PH. Sleep problems and daily functioning in children with ADHD: An investigation of the role of impairment, ADHD presentations, and psychiatric comorbidity. J Atten Disord. 2017;21(9):731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yerys BE, Wallace GL, Sokoloff JL, Shook DA, James JD, Kenworthy L. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms moderate cognition and behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2009;2(6):322–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richdale AL, Schreck KA. Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(6):403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corkum P, Moldofsky H, Hogg-Johnson S, Humphries T, Tannock R. Sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impact of subtype, comorbidity, and stimulant medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein MA. Unravelling sleep problems in treated and untreated children with ADHD. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999;9(3):157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malow BA, Marzec ML, McGrew SG, Wang L, Henderson LM, Stone WL. Characterizing sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders: a multidimensional approach. Sleep. 2006;29(12):1563–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortese S, Faraone SV, Konofal E, Lecendreux M. Sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of subjective and objective studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):894–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreck KA, Mulick JA. Parental report of sleep problems in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(2):127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Hubbard JA, Fabes RA, Adam JB. Sleep disturbances and correlates of children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2006;37(2):179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taira M, Takase M, Sasaki H. Sleep disorder in children with autism. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52(2):182–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beebe DW. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin. 2011;58(3):649–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig F, Margari F, Legrottaglie AR, Palumbi R, De Giambattista C, Margari L. A review of executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denckla MB. A theory and model of executive function: A neuropsychological perspective. Published online 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA, Mark Cummings E, Keller P. Sleep disruptions and emotional insecurity are pathways of risk for children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev. 2002;73(2):405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider HE, Lam JC, Mahone EM. Sleep disturbance and neuropsychological function in young children with ADHD. Child Neuropsychol. 2016;22(4):493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calhoun SL, Pearl AM, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Durica KC, Mayes SD, Murray MJ. Sleep Disturbances Increase the Impact of Working Memory Deficits on Learning Problems in Adolescents with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. Published online 2019:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cremone-Caira A, Buirkle J, Gilbert R, Nayudu N, Faja S. Relations between caregiver-report of sleep and executive function problems in children with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;94:103464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riccio CA, Gomes H. Interventions for executive function deficits in children and adolescents. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2013;2(2):133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayes SD, Calhoun SL. Variables related to sleep problems in children with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2009;3(4):931–941. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shields GS, Moons WG, Tewell CA, Yonelinas AP. The effect of negative affect on cognition: Anxiety, not anger, impairs executive function. Emotion. 2016;16(6):792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jarrett MA, Ollendick TH. A conceptual review of the comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and anxiety: Implications for future research and practice. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(7):1266–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert A, Tessier S, Rochette A-C, Scherzer P, Mottron L, Godbout R. Poor sleep affects daytime functioning in typically developing and autistic children not complaining of sleep problems: A questionnaire-based and polysomnographic study. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;23:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarrett MA, Wolff JC, Davis TE, Cowart MJ, Ollendick TH. Characteristics of Children With ADHD and Comorbid Anxiety. J Atten Disord. Published online 2016. doi: 10.1177/1087054712452914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. Published online 2000. doi: 10.1093/sleep/23.8.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24(5):659–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop SL. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, (ADOS-2, Modules 1-4). Los Angeles, Calif West Psychol Serv. Published online 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reich W, Leacock N, Shanfeld K. DICA-IV Diagnostic Interview for children and Adolescents-IV [Computer software]. Multi-Health Systems. Inc, Toronto. Published online 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ambrosini PJ, Metz C, Prabucki K, Lee J. Videotape reliability of the third revised edition of the K-SADS. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28(5):723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales--Revised: CRS-R. Multi-Health Systems North Tonawanda, NJ; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conners CK. Conners third edition (Conners 3). Los Angeles, CA: West Psychol Serv. Published online 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wechsler D. WISC-III: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children: Manual. Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raiford SE, Drozdick L, Zhang O. Q-interactive® Special Group Studies: The WISC®–V and Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Accompanying Language Impairment or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Q Interact Tech Rep. 2015;11. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nader A-M, Jelenic P, Soulières I. Discrepancy between WISC-III and WISC-IV cognitive profile in autism Spectrum: what does it reveal about autistic cognition? PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wechsler D The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence. Published online 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumont R, Willis JO. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test–Second Edition. Encycl Spec Educ. Published online 2008:2130–2131. [Google Scholar]

- 46.DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale—IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez R, Vance A, Watson SD. Structure of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition in a group of children with ADHD. Front Psychol. 2016;7:737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearson. WISC-V: Subtests and the Scales: Primary, Ancillary and Complementary Indexes. Published online 2018.

- 49.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soto T. Processing speed index. Encycl Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;1:2380–2381. [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Belmont Hollingshead A Four Factor Index of Social Status. Department of Sociology, Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura BJ, Ebesutani C, Bernstein A, Chorpita BF. A psychometric analysis of the child behavior checklist DSM-oriented scales. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2009;31(3):178–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cripe LI. The Ecological Validity of Executive Function Testing. Delray Beach; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruff RM. A friendly critique of neuropsychology: Facing the challenges of our future. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18(8):847–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bériault M, Turgeon L, Labrosse M, et al. Comorbidity of ADHD and anxiety disorders in school-age children: impact on sleep and response to a cognitive-behavioral treatment. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(5):414–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schreck KA, Mulick JA, Smith AF. Sleep problems as possible predictors of intensified symptoms of autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2004;25(1):57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sedky K, Bennett DS, Carvalho KS. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and sleep disordered breathing in pediatric populations: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(4):349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malow BA, McGrew SG, Harvey M, Henderson LM, Stone WL. Impact of treating sleep apnea in a child with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34(4):325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson CR, DeMand A, Lecavalier L, et al. Psychometric properties of the children’s sleep habits questionnaire in children with autism spectrum disorder. Sleep Med. 2016;20:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katz T, Shui AM, Johnson CR, et al. Modification of the children’s sleep habits questionnaire for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(8):2629–2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verhoeff ME, Blanken LME, Kocevska D, et al. The bidirectional association between sleep problems and autism spectrum disorder: a population-based cohort study. Mol Autism. 2018;9(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]