Abstract

Neoplasm development in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients treated with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) has been widely discussed. The aim of this work is to determine neoplasm frequency, relationship with the prescription pattern of DMTs, and influence of the patients’ baseline characteristics. Data from 250 MS outpatients were collected during the period 1981–2019 from the medical records of the Neurology Service of the HUPM (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar)—in Southern Spain—and analysed using Cox models. Neoplasm prevalence was 24%, mainly located on the skin, with cancer prevalence as expected for MS (6.8%). Latency period from MS onset to neoplasm diagnosis was 10.4 ± 6.9 years (median 9.30 [0.9–30.5]). During the observation period β-IFN (70.4% of patients), glatiramer acetate (30.4%), natalizumab (16.8%), fingolimod (24.8%), dimethyl fumarate (24.0%), alemtuzumab (6.0%), and teriflunomide (4.8%) were administered as monotherapy. Change of pattern in step therapy was significantly different in cancer patients vs unaffected individuals (p = 0.011) (29.4% did not receive DMTs [p = 0.000]). Extended Cox model: Smoking (HR = 3.938, CI 95% 1.392–11.140, p = 0.010), being female (HR = 2.006, 1.070–3.760, p = 0.030), and age at MS diagnosis (AGE-DG) (HR = 1.036, 1.012–1.061, p = 0.004) were risk factors for neoplasm development. Secondary progressive MS (SPMS) phenotype (HR = 0.179, 0.042–0.764, p = 0.020) and treatment-time with IFN (HR = 0.923, 0.873–0.977, p = 0.006) or DMF (HR = 0.725, 0.507–1.036, p = 0.077) were protective factors. Tobacco and IFN lost their negative/positive influence as survival time increased. Cox PH model: Tobacco/AGE-DG interaction was a risk factor for cancer (HR = 1.099, 1.001–1.208, p = 0.049), followed by FLM treatment-time (HR = 1.219, 0.979–1.517). In conclusion, smoking, female sex, and AGE-DG were risk factors, and SPMS and IFN treatment-time were protective factors for neoplasm development; smoking/AGE-DG interaction was the main cancer risk factor.

Subject terms: Neurology, Risk factors

Background

Although survival after the onset of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) has historically increased for 17 years, as reflected in the first works 41 years ago, patient life expectancy is, on average, 7 years below the general population data1. While there are different estimations about the increased risk for all-cause mortality (up to threefold), everyone agrees that MS itself is the main cause of death2,3.

Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have been the most important advance in MS treatment, from the so-called first-generation drugs, β-interferon (IFN) and glatiramer acetate (GA), approved in the mid-1990s, until the introduction of the latest drugs in the 2010s, such as fingolimod (FLM), alemtuzumab (ALB), dimethyl fumarate (DMF), teriflunomide (TRF), or the most recently approved purine analogue, cladribine4. Despite their benefits, undesirable effects are expected, especially in relation to infection and malignancy5. IFN liver failure or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy from natalizumab (NTB), although not frequent, are seen as possible threats in routine clinical practice, unlike the development of neoplasms, a rare but dangerous side effect.

In the literature, we found a disparity in the data for both neoplasm frequency in MS patients and the role of DMTs in the neoplasm development, from an increase in cancer-related deaths (1.9-fold)6 to normal or decreased cancer prevalence, although the hazard risk depends on the type of tumour7,8. Increased cancer risk has been observed among patients treated with IFN, GA, NTB, and ALB9,10. The development of skin cancer is contemplated in the technical information about GA, FLM (basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers, Bowen’s disease, melanoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma), and ALB (papilloma) (available at http://www.ema.europa.eu, European Medicines Agency, EMA, last accesed May 2021).

Therefore, the aim of this work is to investigate the therapeutic pattern followed and its relationship with the incidence of neoplasia in MS outpatients. We hypothesise that DMTs could constitute risk factors for the development of neoplasia. Patients’ baseline characteristics were considered for their possible contribution to the development of neoplasms.

Methods

Patient recruitment

This retrospective study was based on outpatients from the Department of Neurology at the Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (HUPM), attended to in consultation from onset of MS between 1981 and 2019. According to the Spanish Statistical Office, the area served by HUPM had an average population of 220 thousand during this period (data available at http://www.ine.es, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE). The data source was the digital medical record used by neurologists conducting a multidisciplinary team. Other independently-trained team members carried out data extraction and statistical analysis. Individuals previously suffering from a neoplasm or diagnosed with Clinically Isolated Syndrome were excluded. As a result, 314 consecutive cases were analysed, 250 of which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The last case was diagnosed in September 2017, and the follow-up of patients ended on the last database registered individual (March 31, 2019).

Measures

The analysed variables were: (a) demographic and baseline characteristics: sex, age at MS onset (AGE-DG); disease phenotype; as possible contributing factors, neoplasm family history and smoking; (b) factors related to neoplasm development: presence and number of neoplasms; malignancy/benignity; tumour lineage; age at neoplasm onset; latency period from the start of DMTs until neoplasm appearance c) factors related to the medication received: type and number of drugs; use order; treatment time for each drug; length of treatment.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage of observed data; numeric variables were represented as mean ± standard deviation and median (minimum–maximum). Association between categorical variables was contrasted by χ2 test, or if these conditions were not verified, by Fisher’s exact test. Quantitative variable comparisons were performed using the Student’s t-test. Associations were considered significant when p < 0.05. For each patient, the observation period (survival time) started with MS diagnosis until neoplasm appearance or the end of the study (censored case).

Several covariate analyses were performed to estimate the role of DMTs and other possible contributing factors to neoplasm development. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to analyse the predictors associated with the hazard rate (HR), with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For assessing the proportional hazard (PH) for each predictor of interest, we also estimated p-values between the ranked survival and the residuals. When the predictors did not satisfy the PH assumption, an extended Cox model was used. For this purpose, we included time-dependent variables to measure the interaction factor with time exposure11. The data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 and Epidat 3.1 software.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Comité de Ética de la Investigación de Cádiz. Servicio Andaluz de Salud. Consejería de Salud. Junta de Andalucía. HUPM. Av. Ana de Viya 21, 11009 CÁDIZ (SPAIN) (phone + 0034 956002100) (ceic.hpm.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es). The need of the informed consent was waived by the Comité de Ética de la Investigación de Cádiz. All the experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Patient baseline features

Patient baseline features were registered in Table 1. Women accounted for 63.2% (n = 158) of the individuals. Mean AGE-DG was 34.0 ± 11.3 years (median 32.0 [13–71)], mostly ranging from 20–40 years (62.4%, n = 156). Relapsing–remitting variant (RRMS) (83.2%, n = 208) was the predominant medical condition. Neoplasm family history was present in 10.4% (n = 26) and tobacco consumption in 44% (n = 110) of individuals. In particular, 24% (n = 60) developed some kind of neoplasm, alone or successively. Five patients suffered from a second (n = 4) or a third process (n = 1). Out of the sampled patients, 6.8% (n = 17, 28.3% of neoplastic patients) suffered malignancy and two of these individuals presented benign tumour. Mean age at tumour diagnosis was 46.2 ± 11.3 years (median 45.5 [26–80]) for neoplasm and 52.1 ± 8.4 for malignancy (median 53.0 [37–69]). Feminine gender, smoking, and family history were significantly present in neoplasm patients as compared to patients who did not present these characteristics (p < 0.05). Cancer patients were older at AGE-DG (39.8 ± 12.3 years, median 40 [21–64)] than the remaining individuals (33.58 ± 11.12, median 32.0 [13–71], n = 233) (mean (p = 0.027), median (p = 0.043)).

Table 1.

Patient baseline features.

| TOTAL** (N = 250) | NEO (n = 60) | NNEO (n = 190) | p* | CANCER (n = 17) | NCANCER (n = 233) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman, n(%) | 158 (63.2) | 46 (76.7) | 112 (58.9) | 0.013 | 12 (70.6) | 146 (62.7) | 0.513 |

| Age at onset | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 34.0 ± 11.3 | 35.6 ± 11.5 | 33.5 ± 11.2 | 0.205 | 39.8 ± 12.3 | 33.58 ± 11.12 | 0.027 |

| Median (range) | 32.0 (13–71) | 34.0 (18–71) | 32.0 (13–67) | 0.271 | 40 (21–64) | 32.0 (13–71) | 0.043 |

| Age Intervals, n(%) | 0.264 | 0.085 | |||||

| < 20 years | 21 (8.4) | 2 (3.3) | 19 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (9.0) | ||

| 20–40 years | 156 (62.4) | 40 (66.7) | 116 (61.1) | 9 (52.9) | 147 (63.1) | ||

| > 40 years | 73 (29.2) | 18 (30.0) | 55 (28.9) | 8 (47.1) | 65 (27.9) | ||

| MS phenotype, n(%) § | 0.286 | 0.297 | |||||

| RRMS | 208 (83.2) | 51 (85.0) | 157 (82.7) | 12 (70.5) | 196 (84.1) | ||

| PPMS | 19 (7.6) | 6 (10.0) | 13 (6.8) | 2 (11.8) | 17 (7.3) | ||

| SPMS | 21 (8.4) | 2 (3.3) | 19 (10) | 2 (11.8) | 19 (8.2) | ||

| RPMS | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Smoking, n(%) | 110 (44) | 35 (58.3) | 75 (39.5) | 0.010 | 9 (52.9) | 75 (39.5) | 0.442 |

| Neo family history, n(%) | 26 (10.4) | 11 (18.3) | 15 (7.9) | 0.021 | 2 (11.8) | 24 (10.3) | 0.849 |

| Average follow-up time (years)¥ | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 12.1 ± 7.6 | 10.4 ± 6.9 | 12.8 ± 7.7 | 0.031 | 12.2 ± 7.6 | 12.2 ± 7.6 | 0.992 |

| Median (range) | 11.2 (0.9–37.5) | 9.4 (0.9–30.5) | 11.6 (1.3–37.5) | 0.024 | 9,9 (2.3–27.8) | 11.2 (0.9–37.5) | 0.972 |

Comparison of individuals affected vs unaffected by neoplasia.

*p value from the χ-test or T-test.

§ RRMS: relapsing–remitting MS; PPMS: primary progressive MS; SPMS: secondary progressive MS; PRMS: progressive-relapsing MS.

¥Time from MS diagnosis to first neoplasm/cancer appearance or end of the observation period (censored cases).

**TOTAL: whole sample; NEO: patients with neoplasm; NNEO: neoplasm-free patients; CANCER: patients with cancer; NCANCER: cancer-free patients.

Mean MS duration was 13.1 ± 7.8 years. Table 1 shows the observation periods. The latency period from MS to neoplasm appearance was 10.4 ± 6.9 years (median 9.30 [0.9–30.5]), significantly less than the observation period for censured cases (mean 12.8 ± 7.7, median 11.6 [1.3–37.5]) (mean p = 0.031, median p = 0.024).

Tumour lineage

Table 2 indicates tumour frequency, site, developmental lineage, and cell line. Sixty patients developed some kind of neoplasm (n = 66), 74.2% were benign (n = 49), with melanocytic nevus (18.2% of neoplasms, n = 12) and uterine myoma (12.1%, n = 8) being most common. The most frequent locations were cutaneous tissue (keratosis, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, basal cell carcinoma) (37.9%, n = 25) and the myometrium (12.1%, n = 8). The neoplasms originated in the ectoderm (65.2%, n = 43), mesoderm (27.3%, n = 18), or had a mixed origin (7.5%, n = 5). The epithelial cell line was most frequent (38.3% of neoplasm, n = 27), followed by the melanocytic line (21.2%, n = 14). Fourteen malignant tumours were carcinomas.

Table 2.

Neoplasm types and frequency.

| Neoplasm type (n=66) | Frecuency n (%) | Cell line | Embryogenic lineage |

|---|---|---|---|

| BENIGN (n = 49, 74.2%) | |||

| Pleomorphic parotid adenoma | 1 (1.5) | Mixed | Mixed |

| Hürtle cell thyroid adenoma | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Liver angioma | 1 (1.5) | Blood vessel | Mesodermal |

| Renal angiomyolipoma | 1 (1.5) | Mixed | Mixed |

| Breast fibroadenoma | 3 (4.5) | Mixed | Mixed |

| Fibroma | 2 (3.0) | Connective | Mesodermal |

| MGUS§ | 1 (1.5) | Hematopoietic | Mesodermal |

| Ganglion (interphalangeal) | 1 (1.5) | Connective | Mesodermal |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Lipoma | 2 (3.0) | Adipose tissue | Mesodermal |

| Cerebral meningioma | 2 (3.0) | Meninges | Mesodermal |

| Uterine myoma | 8 (12.1) | Myometrium | Mesodermal |

| Acoustic neurilenoma | 1 (1.5) | Nervous tissue | Ectodermal |

| Brachial plexus neurilenoma | 1 (1.5) | Nervous tissue | Ectodermal |

| Common melanocytic nevus | 12 (18.2) | Melanocytes | Ectodermal |

| Uterine endocervical polyp | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Hyperplastic colonic polyp | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Laryngeal polyp | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Gallbladder benign polyp | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Vocal polyp | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Actinic keratosis | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Seborrheic keratosis | 5 (7.6) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| MALIGNANT (n = 17, 25.8%) | |||

| Breast adenocarcinoma | 2 (3.0) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma | 2 (3.0) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 2 (3.0) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Basal-cell carcinoma | 5 (7.6) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 2 (3.0) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Ovarian serous Carcinoma | 1 (1.5) | Epithelial | Ectodermal |

| Melanoma | 2 (3.0) | Melanocytes | Ectodermal |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia | 1 (1.5) | Hematopoietic | Mesodermal |

§MGUS: Monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance.

DMT pattern and neoplasm development

A total of 92.9% (n = 232) of individuals received DMTs, 41.4% (n = 96) of which continued on their first therapy, while 58.6% (n = 136) was required to switch drugs due to inefficacy or non-compliance. According to clinical criteria, 18 patients remained untreated (mean AGE-DG 47.1 ± 11.0, median 48.5 [29–67]; mean age at neoplasm diagnosis was 62.2 ± 5.1, median 62.5 [54–69]; 44.4% women). The drugs administered as monotherapy were IFN (n = 176, 70.4% of patients), GA (n = 76, 30.4%), NTB (n = 42, 16.8%), FLM (n = 62, 24.8%), DMF (n = 60, 24.0%), TRF (n = 12, 4.8%), and ALB (n = 15, 6.0) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in therapy pattern between neoplasm-affected and unaffected patients.

| Drug n (%) | Total n = 250 | NEO (n = 60) | No NEO (n = 190) | p | CANCER (n = 17) | No CANCER (N = 233) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 18 (7.2) | 6 (10) | 12 (6.3) | 0.336 | 5 (29.4) | 13 (5.6) | 0.000 |

| INF | 176 (70.4) | 42 (70) | 134 (70.5) | 0.938 | 10 (58.8) | 166 (71.2) | 0.279 |

| GA | 76 (30.4) | 23 (38.3) | 53 (27.9) | 0.125 | 4 (23.5) | 72 (30.9) | 0.524 |

| NTB | 42 (16.8) | 9 (15.0) | 33 (17.4) | 0.669 | 2 (11.8) | 40 (17.2) | 0.565 |

| FLM | 62 (24.8) | 15 (25.0) | 47 (24.7) | 0.967 | 5 (29.4) | 57 (24.5) | 0.648 |

| DMF | 60 (24.0) | 9 (15.0) | 51 (26.8) | 0.061 | 3 (17.6) | 57 (24.5) | 0.525 |

| TRF | 12 (4.8) | 4 (6.7) | 8 (4.2) | 0.438 | 0 (0.0) | 12 (5.2) | 0.338 |

| ALB | 15 (6.0) | 2 (3.3) | 13 (6.8) | 0.318 | 1 (5.9) | 14 (6.0) | 1.000 |

| No. of drugs administered, n (%) | 0.813 | 0.011 | |||||

| 0 | 18 (7.2) | 6 (10) | 12 (6.3) | 5 (29.4) | 13 (5.6) | ||

| 1 | 96 (38.4) | 22 (36.6) | 74 (38.9) | 3 (17.6) | 92 (39.5) | ||

| 2 | 82 (32.8) | 19 (31.7) | 63 (33.2) | 7 (41.2) | 76 (32.6) | ||

| > 2 | 54 (21.6) | 13 (21.7) | 41 (21.6) | 2 (11.8) | 52 (22.3) | ||

| Treatment length (years) | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.2 ± 5.6 | 8.8 ± 6.0 | 8.1 ± 5.5 | 0.500 | 8.3 ± 6.9 | 8.2 ± 5.5 | 0.865 |

| Median (range) | 8.3 (0.0–22.8) | 8.7 (0.0–22.8) | 8.0 (0.0–22.4) | 0.412 | 8.9 (0.0–22.0) | 8.3 (0.0–22.8) | 0.977 |

| Treatment length of each drug (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (range) | ||||||

| IFN | 4.6 ± 5.6 | 1.8 (0.0–22.0) | |||||

| GA | 1.5 ± 3.1 | 0.0 (0.0–13.3) | |||||

| NTZ | 0.7 ± 2.0 | 0.0 (0.0–9.8) | |||||

| FLM | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.0 (0.0–7.5) | |||||

| DMF | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.0 (0.0–3.7) | |||||

| TLF | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.0 (0.0–3.6) | |||||

| ALB | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | |||||

| Drug prescribing frequency in the successive changes on sequential therapy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 1st | At 2nd | At 3rd | At 4th | At 5th | |||

| n (%) (referred to whole sample [n = 250]) | |||||||

| IFN | 162 (64.8) | 14 (5.6) | 4 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | ||

| GA | 38 (15.2) | 37 (14.8) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | ||

| NTB | 7 (2.8) | 23 (9.2) | 10 (4.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0 | ||

| FLM | 6 (2.4) | 28 (11.2) | 25 (10.0) | 3 (1.2) | 0 | ||

| DMF | 14 (5.6) | 29 (11.6) | 9 (3.6) | 8 (3.2) | 0 | ||

| TRF | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.0) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0,4) | 0 | ||

| ALB | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.2) | 7 (2.8) | 1 (0.4) | ||

For the case of neoplastic patients, 10% did not receive treatment, while 36.7% (n = 22) were being treated with their first drug, 31.7% (n = 19) with a second drug, and 13 (21.7%) with a third, fourth, or fifth option, with no differences with respect to non-neoplastic patients. A total of 29.4% (n = 5) of cancer patients did not receive treatment vs cancer-free individuals (5.1%, n = 13) (p = 000), with differences between both groups also observed in the escalating therapy (p = 0.011) (Table 3).

Treatment duration, overall and specifically for each drug, is recorded in Table 3. Median treatment length was around eight years in all groups (whole sample 8.2 ± 5.6 years, median 8.3 [0.0–22.8]). IFN therapy had the longest duration of treatment (mean 4.6 ± 5.6 years, median 1.8 [0.0–22.0)]. Mean treatment time with DMF resulted significantly lower in neoplasm patients (mean 0.3 ± 0.7, median 0.0 [0–3.7]) vs unaffected individuals (mean 0.6 ± 1.1, median 0.0 [0.0–3.7]) (mean (p = 0.005), median (p = 0.43)).

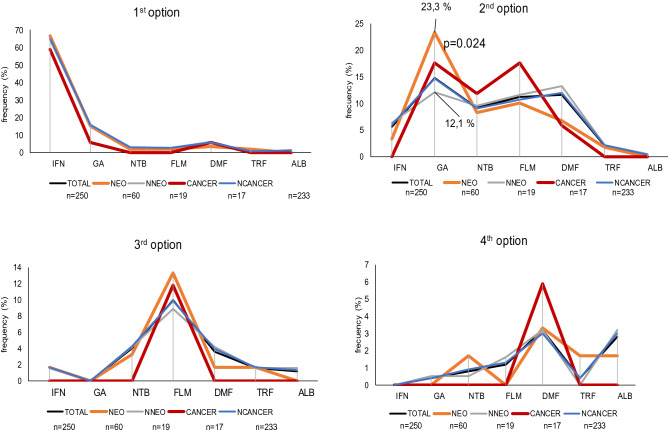

Figure 1 shows the drug prescription frequency in sequential therapy for the whole sample (detailed in Table 3) as well as the four groups studied (NEO: patients with neoplasm, NNEO: neoplasm-free patients; CANCER: patients with cancer; NCANCER: cancer-free patients). IFN was the main first choice in all groups (64.8%, n = 162). As a second option, a wider range of drugs was prescribed, with GA being used significantly more in neoplastic (23.3%, n = 14) as compared to “healthy” patients (12.1%, n = 23) (p = 0.024). Individuals who received IFN as a third option had previously received it as a first option. Only one patient was required to change to a fifth drug (in the following order: IFN, GA, FLM, DMF, ALB) during the observation period and developed malignancy.

Figure 1.

Drug prescription frequency in the therapeutic sequence. Percentages were calculated in relation to the group total cases.

Cox proportional hazard risk (HR) models to evaluate the contribution of variables to neoplasm development

Variables with statistical significance (p < 0.05) or no significance but with possible long-term influence (p < 0.15), estimated by the Wald test, are recorded in Table 4. The PH hypothesis was not admissible for smoking (TAB) (p(PH) = 0.046), duration of IFN use (TIFN) (p(PH) = 0.002), and covariates with p(PH)-values between 0.662–0.986. This was solved using an extended Cox model, including two time-dependent covariates: a) survival time (ST) multiplied by TAB (STxTAB) and b) ST multiplied by TINF-r (STxTINF-r) (TIFN was previously categorised as TINF-r = 0 and TINF-r > 0). HR values were constant throughout the follow-up period, except for variables TAB and TINF.

Table 4.

Cox analysis to assess the risk of neoplasm development.

| Coef | SE | Wald | p | HR | 95% CI for HR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extended Cox model to evaluate influence of covariates on the of the first neoplasm appearance | |||||||

| AGE-DG | 0.035 | 0.012 | 8.417 | 0.004 | 1.036 | 1.012–1.061 | |

| GEN | 0.696 | 0.321 | 4.718 | 0.030 | 2.006 | 1.070–3.760 | |

| TAB | 1.371 | 0.531 | 6.675 | 0.010 | 3.938 | 1.392–11.140 | |

| HYS | 0.537 | 0.354 | 2.302 | 0.129 | 1.711 | 0.855–3.426 | |

| SPMS | -1.723 | 0.742 | 5.396 | 0.020 | 0.179 | 0.042–0.764 | |

| TINF | -0.080 | 0.029 | 7.682 | 0.006 | 0.923 | 0.873–0.977 | |

| TDMF | -0.322 | 0.182 | 3.119 | 0.077 | 0.725 | 0.507–1.036 | |

| ST x TAB | -0.076 | 0.045 | 2.930 | 0.087 | 0.926 | 0.849–1.011 | |

| ST x TINF | 0.053 | 0.033 | 2.667 | 0.102 | 1.055 | 0.989–1.124 | |

| Sample size = 250; − 2LnLikelihood = 524.849; LR (M1-M0) = 45.849 (9df) ; p = 0.000 | |||||||

| Coef | SE | Wald | p | HR | 95% CI for HR | p(PH)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox regression model to estimate influence of covariates in malignancy | |||||||

| AGE-DG | 0.055 | 0.029 | 3.626 | 0.057 | 1.056 | 0.998–1.117 | 0.129 |

| TAB | -3.228 | 2.008 | 2.586 | 0.108 | 0.040 | 0.001–2.027 | 0.849 |

| TFLM | 0.198 | 0.112 | 3.126 | 0.077 | 1.219 | 0.979–1.517 | 0.133 |

| AGE-DG x TAB | 0.095 | 0.048 | 3.885 | 0.049 | 1.099 | 1.001–1.208 | 0.675 |

| Sample size = 250; − 2LnLikelihood = 133.865; LR (M1-M0) = 22.411 (9df) ; p = 0.000 | |||||||

AGE-DG: age at MD diagnosis; GEN: gender; TAB: smoking; HYS: family history of neoplasm; SPMS: secondary progresive MS phenotype; TINF: time of INF use; TDMF: time of DMF use; TFLM: time of FLM use; ST: survival time (neoplasm-free time).

*We have included non-significant p (PH)-values to contrast each covariate.

Using this model (Table 4), we found that for each increasing year of MS diagnosis, risk increases 3.6% (HR = 1.036, CI95% 1.012–1.061, p = 0.004), women have twice the risk than men (HR = 2.006, CI95% 1.070–3.760, p = 0.030), and smoking quadruples the risk of development of a first neoplasm (HR = 3.938, CI95% 1.392–11.140, p = 0.010). To a lesser extent, family history of neoplasm increased risk 1.7 times (HR = 1.711, CI95% 0.855–3.426, p = 0.0129). Secondary progressive MS (SPMS) was found to be a protective risk factor with ≈1/5 the risk of neoplasm development with respect to other MS phenotypes (HR = 0.179, CI95% 0.042–0.764, p = 0.020).

TINF (HR = 0.923, CI95% 0.873–0.977, p = 0.006) or duration of DMF use (TDMF) (HR = 0.725, CI95% 0.507–1.036, p = 0.077) acted as risk protectors in such a way that for each treatment year with IFM or DMF, neoplasm risk decreased by 8% or 27%, respectively. STxTAB (HR = 0.926, CI95% 0.849–1.011, p = 0.087) and STxTINF (HR = 1.055, CI95% 0.989–1.124, p = 0.102), shown as survival time (free-neoplasm time), modified the predicted risks so that with each passing year, both smoking risk and protective nature of TIFN decreased.

A second Cox proportional HR model analysed the predictors for cancer-free time (Table 4). AGE-DG (HR = 1.056, CI95% 0.998–1.117, p = 0.057) and TAB (HR = 0.040, CI95% 0.001–2.027, p = 0.108) influenced malignancy. Increased age at diagnosis raised the risk, while smoking appeared to be a protective factor. However, when variable-interaction effect was estimated (HR = 1.099, CI95% 1.001–1.208, p = 0.049), AGE-DG, as a risk factor, increased in smokers and TAB increased cancer risk as AGE-DG increased. Thus, smoking becomes a risk factor for patients over the sampled mean age (34 years). Note that at this age, the HR of TAB + AGE-DG TAB is exp(− 3.228 + 34 * 0.095) = 1.002. Finally, duration of FLM use was a risk factor (HR = 1.219, CI95% 0.979–1.517, p = 0.077) for cancer development.

Discussion

Are detected frequency and malignancy type similar to that of the general population? In the European population12, breast (13.5% of all cancer cases), prostate (12.1%), and lung cancer (11.9%) represent 37.5% of all tumours, in a similar proportion to our data (35.3% of cancers, n = 7). However, in our sample, skin melanoma represented 11.8% (2 of 17), while, in Europe, it is the sixth most frequent cancer (3%); although non-melanoma skin cancer (particularly basal cell carcinomas) data were similar in sampled individuals (71.4% of cutaneous cancers) vs the general population (70–80%).

We detected 21 types of benign neoplasms, many of them common in individuals over the age of 50: MEGUS in 1% > 50; Hürtle-cell adenoma of the thyroid in 0.5–1% of adults; hyperplastic colonic polyps in 30% of adults, 50% in the elderly13. Uterine myoma was the second most frequent neoplasm in the patients sampled, in consonance with myometrial tumours representing 20% of benign tumours in women (in our sample, 23.3% [n = 8] of 37 women suffered from benign processes)14.

Several studies suggested an increased risk of breast and central nervous system cancer, or benign neoplasm (meningioma, adenoma), but not especially skin cancer7,9,15. On the contrary, other works detected a decreased HR16: intense MS immune activity or immunomodulatory treatment has been hypothesised as an explanation17. In this sense, the Cox analysis showed that increased age at MS onset implied a greater risk of both neoplasm and malignancy. Would this be due to a “protective” effect of the MS treatment, or to senility itself? Untreated patients were older; both at MS onset and cancer diagnosis, and 27.8% developed cancer, a higher value than the 13.92% for a Spanish population ≥ 65 under multi-morbidity conditions18.

Moreover, a population-based study (51% women; mean age 47.76 ± 10.99, 77% population > 24 years old) reported a prevalence of 3%19. Despite this, cancer prevalence in our sample (6.8%) was in the range of 2.6–7.3% recorded in the MS literature10,16,20. Neoplasm type and relative frequency were those expected in the general population, except for skin tumours (37.9%, 25 of 66 of neoplasms diagnosed), being the most prevalent. This is an expected side-effect of DMTs, recorded in the adverse reactions section of the Summary of Product Characteristics for some drugs such as FLM, as mentioned above, or GA: ≥ 1/100 to < 1/10 of GA-treated patients could develop benign skin neoplasms; ≥ 1/1000 to < 1/10 could develop skin cancer. Technical information on other more recently introduced active substances such as NTB (00’) and ALB (10’s) includes a recommendation for additional monitoring for any suspicious reaction detected (http://www.ema.europa.eu), but this is rather directed at other health-compromising side-effects (hepatic, immunological, or haematological effects). However, NTB has been directly linked to melanoma replication, invasion, and migration via blockage of α4-integrin expressed in tumour cells, and to the development of melanoma in treated patients21.

Epidemiological studies on DMTs show data disparity4, although second-line immunosuppressants (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone) seem to involve a heightened risk for malignancy22. However, the relationship between immunotherapy and neoplasm development is inconclusive since some of these drugs are employed as coadjuvants or even anti-cancer drugs (ALB, cladribine, mitoxantrone) (http://www.ema.europa.eu), or are under consideration (FLM, TER) as oncologic therapeutic options7,23. This implies their subjection by Medicines Agencies to the monitoring of the possible development of malignancy in treated MS patients. For example, in the safety analysis recorded in the technical information, the overall incidence of cancer was twofold higher in cladribine-treated patients compared to patients who received a placebo (http://www.ema.europa.eu)24. It should be also highlighted that our patients will use them long-term.

Moreover, we found in our sample that TIFN and TDMF protected against neoplasm development, although INF and GA have been linked to cancer development9,25–27. However, a regressive effect of IFN has been casually observed in isolated neoplasms28, as well as a 32% lower mortality related to untreated patients29. Regarding DMF, which was recently licensed, a few studies have been published with a short follow-up, confirming its safe use (cancer was detected in only 0.9% of patients)30.

On the other hand, as we estimated (HR = 1.219, p = 0.077), a high risk could be expected from FLM use, supported by register-based cohort studies31, reviews27, or technical information: basal cell carcinoma being common (≥ 1/100– < 1/10), squamous cell carcinoma being uncommon (≥ 1/1000- < 1/100), Kaposi’s sarcoma or Merkel cell carcinoma, as well as cases of lymphoma being rare (≥ 1/10,000– < 1/1000) (http://www.ema.europa.eu).

SPMS acted as a protective factor for neoplasm development, but large retrospectives studies did not find differences in phenotype contribution with respect to a decrease in cancer risk32. A possible explanation for our finding could be the distinct cytokine and adhesion molecule expression pattern of MS variants33. This should be extensively examined. Likewise, the influence of the patient's disability status on the neoplasm development could be considered. The latter is a limitation of our study and, although we did not include this variable like many other papers, some authors have found a low disease process, according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)(≤ 2), in the majority of patients with benign tumours15.

Finally, to understand the extent of neoplasm development in MS patients, genetic predisposal factors and lifestyle must be explored, although some works observe a lack of information in this regard22. Multivariate analysis revealed smoking to be the most significant risk predictor for neoplasm/cancer. Female sex is a risk factor; however, it should be noted that women predominated in our study (19.4%, 13 of 66 had gynaecological neoplasms). Family predisposition was a moderate risk predictor. In fact, a comprehensive study showed that lower cancer risk in MS patients did not coincide with a lower risk in their parents34.

Conclusions

In the patients studied, neoplasm prevalence was 23.4%, with a similar distribution of different types of tumours with respect to the general population, except for skin neoplasm (37.9% of occurring neoplasms). In our sample, 6.8% of patients suffered from cancer, in line with the data observed in other MS-focused studies. The extended Cox model identified smoking as the main risk factor for neoplasm development (HR = 3.938, CI 95% 1.392–11.140, p = 0.010), followed by the female gender (HR = 2.006, p = 0.030), and age at MS diagnosis (HR = 1.036, p = 0.04). SPMS (HR = 0.179, 0.042–0.764, p = 0.020) and treatment time with IFN (HR = 0.923, 0.873–0.977, p = 0.006) or DMF (HR = 0.725, p = 0.077) were protective factors. Tobacco and IFN treatment time lost their negative/positive influence as the result of an increase in survival time. The Cox regression model identified tobacco/AGE-DG a risk factor for cancer (HR = 1.099, CI95%1.001–1.208, p = 0.049), followed by FLM treatment time (HR = 1.219, p = 0.077).

In summary, genetic factor, lifestyle, the inflammatory profile of MS, drug type, and clinical practice interact in a complex manner. The last drugs introduced would require more clinical experience. Perhaps, exposure time of these risk factors should be taken into account, given the long-term nature of the disease.

Author contributions

G.-B.R.: data recording, data analysis and writing original draft. G.-C., J.L.: design of mathematical models to analyse and synthesize study data, and analysis of data. E.-R.R.: clinical attention of patients and provision of anonimized medical records. G.-G.C.: (conceptualization, supervision and revision): design of investigation, and revision of first research and draft manuscript (English redaction, critical review, commentary).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lunde HMB, Assmus J, Myhr KM, et al. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: A 60-year longitudinal population study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):621–625. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jick SS, Li L, Falcone GJ, et al. Mortality of patients with multiple sclerosis: A cohort study in UK primary care. J. Neurol. 2014;261:1508–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7370-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brùnnum-Hansen H, Koch-Henriksen N, Stenager E. Trends in survival and cause of death in Danish patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2004;127:844–850. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melamed E, Lee MW. Multiple sclerosis and cancer: The Ying-Yang effect of disease modifying therapies. Front. Immunol. 2020;10:2954. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subei AM, Ontaneda D. Risk mitigation strategies for adverse reactions associated with the disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(9):759–771. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0277-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lalmohamed A, Bazelier MT, Van Staa TP, et al. Causes of death in patients with multiple sclerosis and matched referent subjects: A population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012;19:1007–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebrun C, Rocher F. Cancer risk in patients with multiple sclerosis: Potential impact of disease-modifying drugs. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:939–949. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyritsis AP, Boussios S, Pavlidis N. Cancer specific risk in multiple sclerosis patients. Crit Rev Oncol / Hematol. 2016;98:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hongell K, Kurki S, Sumelahti M-L, et al. Risk of cancer among Finnish multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019;35:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havrdova E, Arnold DL, Cohen JA, et al. Alemtuzumab CARE-MS I 5-year follow-up durable efficacy in the absence of continuous MS therapy. Neurology. 2017;89(11):1107–1116. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival Analysis: A Self-Learning Text. 2. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, et al. Harrison. Principios de Medicina Interna. McGraw-Hill; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monleon J, Cañete ML, Caballero V, et al. Epidemiology of uterine myomas and clinical practice in Spain: An observational study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018;226:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zadeh AR, Farrokhi M, Etemadifar M, et al. Prevalence of benign tumors among patients with multiple sclerosis. Am. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2015;2(4):127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moisset X, Perie M, Pereira B, et al. Decreased prevalence of cancer in patients with multiple sclerosis: A case–control study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0188120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franks AL, Slansky JE. Multiple associations between a broad spectrum of autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(4):1119–1136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forjaz MJ, Rodíguez-Blázquez C, Ayala A, et al. Chronic conditions, disability, and quality of life in older adults with multimorbidity in Spain. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015;26:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen FB, Pedersen MH, Friis K, et al. A latent class analysis of multimorbidity and the relationship to socio-demographic factors and health-related quality of life. A national population-based study of 162,283 Danish adults. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marrie RA, Reider N, Cohen J, et al. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of cancer in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2015;21(3):294–304. doi: 10.1177/1352458514564489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabol RA, Noxon V, Sarto O, et al. Melanoma complicating treatment with natalizumab for multiple sclerosis: A report from the Southern Network on Adverse Reactions (SONAR) Cancer Med. 2017;6(7):1541–1551. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ragonese P, Aridon P, Vazzoler G, et al. Association between multiple sclerosis, cancer risk, and immunosuppressant treatment: a cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0932-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rupp T, Pelouin O, Genest L, et al. Terapeutic potential of Fingolimod in triple negative breast cancer preclinical models. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(1):100926. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rammohan K, Coyle PK, Sylvester E, et al. The development of cladribine tablets for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: A comprehensive review. Drugs. 2020;80:1901–1928. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achiron A, Barak Y, Gail M, et al. Cancer incidence in multiple sclerosis and effects of immunomodulatory treatments. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2005;89:265–270. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-2229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zadeh AR, Askari M, Azadani NN, et al. Mechanism and adverse effects of multiple sclerosis drugs: a review article. Part 1. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2019;11(4):95–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zadeh AR, Ghadimi K, Ataei A, et al. Mechanism and adverse effects of multiple sclerosis drugs: a review article. Part 2. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2019;11(4):105–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galloway L, Vakili N, Spears J. Spontaneous regression of a parafalcine meningioma in a multiple sclerosis patient being treated with interferon beta-1a. Acta Neurochir. 2017;159(3):469–471. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-3019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingwell E, Leray E, Zhu F, et al. Multiple sclerosis: Effect of beta interferon treatment on survival. Brain. 2019;142:1324–1333. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabin J, Urtiaga S, Pilo B, et al. Tolerability and safety of dimethyl fumarate in relapsing multiple sclerosis: A prospective observational multicenter study in a real-life Spanish population. J. Neurol. 2020;267:2362–2371. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09848-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alping P, Askling J, Burman J, et al. Cancer risk for fingolimod, natalizumab, and rituximab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann. Neurol. 2020;87(5):688–699. doi: 10.1002/ana.25701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kingwell E, Bajdik C, Phillips N, et al. Cancer risk in multiple sclerosis: Findings from British Columbia, Canada. Brain. 2012;135:2973–2979. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hohlfeld R. Immunologic factors in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2004;10:S16–S22. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1026oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahmanyar S, Montgomery SM, Hillert J, et al. Cancer risk among patients with multiple sclerosis and their parents. Neurology. 2009;72(13):1170–1177. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345366.10455.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]