Summary

In genome-wide association studies, ordinal categorical phenotypes are widely used to measure human behaviors, satisfaction, and preferences. However, because of the lack of analysis tools, methods designed for binary or quantitative traits are commonly used inappropriately to analyze categorical phenotypes. To accurately model the dependence of an ordinal categorical phenotype on covariates, we propose an efficient mixed model association test, proportional odds logistic mixed model (POLMM). POLMM is computationally efficient to analyze large datasets with hundreds of thousands of samples, can control type I error rates at a stringent significance level regardless of the phenotypic distribution, and is more powerful than alternative methods. In contrast, the standard linear mixed model approaches cannot control type I error rates for rare variants when the phenotypic distribution is unbalanced, although they performed well when testing common variants. We applied POLMM to 258 ordinal categorical phenotypes on array genotypes and imputed samples from 408,961 individuals in UK Biobank. In total, we identified 5,885 genome-wide significant variants, of which, 424 variants (7.2%) are rare variants with MAF < 0.01.

Keywords: genome-wide association studies, GWAS, phenome-wide association studies, PheWAS, ordinal categorical data, mixed model approach, proportional odds logistic mixed model, POLMM, UK Biobank, saddlepoint approximation, unbalanced phenotypic distribution, food and other preferences, genetic relationship matrix, GRM

Introduction

Large-scale biobanks with hundreds of thousands of genotyped and extensively phenotyped subjects are valuable resources to identify genetic components of complex phenotypes.1,2 In biobanks, ordinal categorical data, which are often collected from surveys, questionnaires, and testing to measure human behaviors, satisfaction, and preferences, are a common type of phenotype.3, 4, 5 For example, a web questionnaire was used for 182,219 UK Biobank participants to collect 150 food and other health behavior-related preferences, all of which are ordinal categorical phenotypes based on a 9-point hedonic scale of liking from 1 (extremely dislike) to 9 (extremely like).6 For ordinal categorical phenotypes, there is no underlying measurable scale, and therefore, it would be inappropriate to treat that phenotype as a quantitative trait and apply the linear regression methods.7, 8, 9 Another approach is to use an arbitrary cutoff to dichotomize the ordinal categorical phenotype into two categories, followed by using a logistic regression method.3 This approach suffers from information loss and, thus, is less powerful.

For binary and quantitative phenotype data analysis, mixed model approaches have been widely used to test genetic associations conditioning on the sample relatedness.7,10 Some state-of-art optimization strategies have been applied to reduce memory usage and computational cost, which makes these mixed model approaches practical for incorporating a dense genetic relationship matrix (GRM) in genome-wide association studies (GWASs).9,11 Another resource-efficient approach, fastGWA, is to use a sparse GRM to adjust for the sample relatedness.12 For binary phenotype analysis, unbalanced case-control ratio can result in inflated type I error rates, and saddlepoint approximation (SPA) has been demonstrated to be more accurate for single-variant analysis,8,9 region-based analysis,13,14 and gene-environment interaction analysis.15 Similarly, the sample size distribution in ordinal categorical data could also be highly unbalanced; that is, the sample size in one category could be dozens of times more than that in other categories. For example, of the UK Biobank participants, more than 90% extremely dislike cigarette smoking and only 1% extremely like it. In ordinal categorical data analysis, the effect of the unbalanced sample size distribution on genetic association tests should also be carefully examined.

In this paper, we propose a scalable and accurate mixed model approach for ordinal categorical data analysis in large-scale GWASs. Our approach, proportional odds logistic mixed model (POLMM), incorporates a random effect into the proportional odds logistic model to control for sample relatedness. POLMM uses penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL) and average information restricted maximum likelihood (AI-REML) algorithms7 to efficiently fit the mixed model and then uses SPA to calibrate p values. We give two closely related versions, DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM. To control for the genetic relatedness between samples, DensePOLMM incorporates a dense GRM and FastPOLMM is a resource-efficient approach that uses a sparse GRM.

We demonstrated that POLMM approaches can efficiently analyze large datasets with hundreds of thousands of genetic related samples, can control type I error rates, and is statistically powerful through extensive simulations as well as real data analysis. Meanwhile, BOLT-LMM, fastGWA, and SAIGE approaches cannot control type I error rates and are less powerful, especially when the phenotypic distribution is unbalanced. DensePOLMM requires comparable computation time and memory usage to SAIGE, and FastPOLMM is more resource-efficient to fit a null mixed model. For example, FastPOLMM requires less than 0.1 h and 4.2 GB memory to fit a null mixed model with around 400,000 subjects. In most scenarios, DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM performed similarly in terms of testing. Only when the number of categories is large (e.g., 10) and polygenic effect size is large (e.g., liability heritability = ), DensePOLMM is slightly more powerful than FastPOLMM by no more than 4.67% and 7.51% when testing common (minor allele frequency, MAF = 0.3) and low-frequency variants (MAF = 0.01), respectively. We applied the FastPOLMM approach to analyze 258 ordinal categorical phenotypes in the UK Biobank data, which includes 408,961 samples from white British participants with European ancestry, and successfully identified 5,885 distinct genome-wide significant variants with clumping, of which, 424 variants (7.2%) are rare variants with MAF < 0.01. All analysis results have been publicly available through a web-based visual server,2 which provides intuitive visualizations at three levels of granularity: genome-wide summaries at the trait level and regional (LocusZoom)16 and phenome-wide summaries at the variant level.

Material and methods

Overview of the POLMM method

The POLMM method contains two main steps: (1) fitting the null mixed model to estimate the variance component and model parameters corresponding to covariates and (2) testing for the association between each single genetic variant and ordinal categorical phenotypes. In step 1, we include covariates such as age, gender, and top SNP-derived principal components (PCs) to adjust for their effects on the phenotype. Then, we save the null model fitting results (including the residuals from the null model) in an R object. In step 2, we load the R object and use it for association testing. This strategy only requires one model fitting across a genome-wide analysis, which greatly reduces computation time.

Proportional odds logistic mixed model

We let denote the sample size and let denote the number of category levels. For subject , we let denote its ordinal categorical phenotype. We consider the following proportional odds logistic mixed model (POLMM)

| (Equation 1) |

where is the cumulative probability of the phenotype conditional on a -dimensional vector of covariates and a hard called or imputed genotype . The cutpoints : were used to categorize the data, and coefficients and are fixed effect sizes of the covariates and genotype. To adjust for sample relatedness, we incorporate an n-dimensional random effect vector following a multivariate normal distribution where is a variance component parameter and is an dimensional GRM. Equation 1 is a natural extension of a logistic mixed model as in SAIGE and GMMAT.7,9,14 If , the phenotype is binary and Equation 1 is a logistic mixed model. Although POLMM is based on the proportional odds assumption, previous studies indicate that it could still be valid with respect to tests when the assumption is violated.17 In “numeric simulations,” we validate that POLMM could still control type I error rates when the ordinal categorical phenotypes were simulated following category logistic model and stereotype model.

For subject , we define a vector as an equivalent representation of the ordinal categorical phenotype : if , then and the other elements in are 0. The conditional log-likelihood function given random effects is

where is the mean of ; that is

Because random vector follows a multivariate normal distribution , the marginal log-likelihood function of is

where log-likelihood function . In Appendix A, we follow a similar framework as in GMMAT7 to use PQL and AI-REML to simultaneously estimate the variance component and other parameters that maximize under the null model . It is well known that PQL can generate a biased estimate for the variance component,9,18,19 but as shown in literature, the bias does not inflate type I error rates in association tests.7,9 Similarly, POLMM also has a biased estimate of the variance component. Through extensive simulation studies and real data analysis, we show that the bias does not inflate type I error rates.

Score test and estimated variance

We let and be the fitted value and under the null hypothesis , respectively. The score is

where

Because that and are estimated under the null model and are the same for all variants, it takes computations to calculate the score for any variant. The estimated variance of the score is where -dimensional covariate-adjusted genotype vector

is an diagonal matrix, and is an matrix where denotes an vector with a 1 in the -th coordinate and zeroes elsewhere. We let block diagonal matrix denote the covariance matrix of as follows:

The dimensional matrix where and . To estimate , we must calculate , which is computationally expensive for a genome-wide analysis. To reduce the computation cost, we use the same strategy as in BOLT-LMM11 and SAIGE.9 First, we use a small number of variants to calculate and and estimate ratio by using the mean of . Then, for each variant to test, we calculate and then estimate . The ratio has been shown approximately constant for all genetic variants with minor allele count (MAC) 20.9,11 When estimating , we increase the number of variants until the coefficient of variation for the ratio estimation is lower than a pre-given cutoff of 0.0025. In both simulation studies and real data analysis, the variant number is usually less than 30. Using optimized strategies, it takes computations to the calculate for each variant. More details about the score test and the estimated variance can be seen in Appendix B.

Saddlepoint approximation

The regular score test assumes that asymptotically follows a normal distribution, which uses only the first two moments. However, when the sample size distribution of different categories is highly unbalanced, the underlying distribution of could be substantially different from a normal distribution, especially when testing low-frequency variants. To accurately calculate p values, we use SPA, which uses the entire cumulant generating function (CGF) to approximate the null distribution. Suppose that is the -th element in vector , we define

then the statistic

Because follows a Berounlli distribution, the CGF of is

We use to approximate CGF of such that the variance from CGF is 1; that is, . The distribution of at the observed test statistic can be approximated by

where

and is the solution of the equation .

We apply a hybrid strategy: if , p values are calculated on the basis of normal approximation in which the variance is ; if , p values are calculated on the basis of SPA. Using this hybrid strategy, we can greatly reduce computation time while controlling type I error rates. In addition, using the fact that many elements of are zeroes (i.e., homozygous major genotypes), we use a fast partially normal approximation method to speed up the computation. Suppose that subjects have at least one minor allele each and the rest have homozygous major genotypes, the fast SPA takes computations to calculate the CGF and its derivatives. More details about the SPA can be seen in Appendix B.

DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM

For quantitative trait analysis, Jiang et al. have demonstrated that using a sparse GRM can reduce computational time and memory usage while still being reliable to control type I error rates.12 However, using a sparse GRM can be less powerful than using a dense GRM because a sparse GRM cannot incorporate polygenic effects. In this paper, we present two closely related versions of POLMM methods to test the null model : DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM.

DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM use dense and sparse GRMs to adjust for sample relatedness, respectively. To make DensePOLMM computationally practical for studies with large sample size , we use strategies as in BOLT-LMM11 and SAIGE9 to reduce computation time and memory cost. Instead of storing an dimensional dense GRM, we compactly store raw genotypes of the genetic variants into a bitwise binary vector and use them when a dense GRM is needed. When fitting the null mixed model and estimating variance , we need to solve linear system , which is challenging because Cholesky decomposition takes computation and very large memory space to invert matrix . For a given vector , we use a preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) approach9 to directly calculate . To make the convergence faster, we use a block diagonal matrix as the preconditioner matrix, where matrix , dimensional matrix , and dimensional vector of ones . Given the same tolerance criterion as in SAIGE, PCG in POLMM usually takes 6–8 iterations to converge, which is ∼1.5 times more than that in SAIGE. This might be because we use a block diagonal matrix in which each block corresponds to one subject as the preconditioner matrix. When updating variance component , we estimate by using Hutchinson’s randomized trace estimator, , where are independent random vectors whose elements are i.i.d. Rademacher random variables.20 In addition, we use Intel Threading Building Blocks (TBB) implemented in the RcppParallel package for the multi-threading computation (see web resources). Using these strategies, DensePOLMM is of the same computation complexity as SAIGE9 and requires memory usage , where is the number of markers used to construct a GRM and is the sample size. On the other hand, FastPOLMM uses a sparse GRM in which all of the small off-diagonal elements (for example, those <0.05) are set to 0. GCTA software21 provides an efficient tool to calculate the GRM for a large-scale dataset. The sparse GRM only needs to be calculated once for one cohort study or biobank.

Leave-one-chromosome-out scheme

To avoid contamination for correlated markers, we implemented an option to apply the leave-one-chromosome-out (LOCO) scheme for DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM methods. If the LOCO scheme is used, we first use all variants to estimate the variance component , and then for each chromosome, we updated the estimation of , and after excluding all variants in the same chromosome. This strategy is the same as SAIGE and BOLT-LMM. For FastPOLMM, we first used the tool GCTA to calculate the GRM for each chromosome and then combined them to calculate GRMs.

Liability threshold model and liability heritability

Equation 1 is equivalent to the following liability threshold model

where is a latent variable and error term follows a logistic distribution with a location parameter of 0 and a scale parameter of 1. The -dimensional random effect vector follows a multivariate normal distribution where is a variance component parameter and is an dimensional GRM. The ordinal categorical phenotype if the latent variable is between cutpoints and . The variances of and are and , respectively. Hence, similar to SAIGE,9 we define a liability heritability . Variance components and 10 correspond to liability heritability 23.3% and 75.2%, respectively.

Numeric simulations

To evaluate the computational efficiency and memory usage of the proposed methods, we randomly sampled subjects from white British UK Biobank participants to analyze an ordinal categorical phenotype, able to confide, which consists of six levels (Figure S1). We excluded 11,163 subjects whose answer was “do not know” or “prefer not to answer” and analyzed 397,798 white British participants. We used 340,447 markers to construct the GRM and incorporated six covariates of sex, birth year, and top four SNP-derived principal components to fit the null mixed model. We compared five methods, including fastGWA, BOLT-LMM, SAIGE, DensePOLMM, and FastPOLMM. Besides the raw phenotype with six categories, we combined some levels to make a new phenotype with three categories to comprehensively evaluate POLMM methods (see Figure S1). For fastGWA and BOLT-LMM, we treated the ordinal categorical phenotype as a quantitative trait from 1 to 6. For SAIGE, we dichotomized the phenotype to a binary phenotype (see Figure S1). For fastGWA and FastPOLMM, we set the cutoff of the sparse GRM at 0.05. All analyses were conducted on CPU cores of Intel Xeon Gold 6138 at 2.00 GHz. In step 1, we used eight CPU cores and recorded the computation time. For SAIGE, fastGWA, and POLMM methods, the null mixed model fitting result can be saved and used for association testing. Hence, the genotype data to test can be divided into multiple chunks for parallel computation. In step 2, we used one CPU core and recorded the computation time. For BOLT-LMM, the model fitting and association testing cannot be separately implemented. We extracted “the time for streaming genotypes and writing output” from log files to record the computation time in step 2. Because FastPOLMM and DensePOLMM are the same when testing genetic association effect, we only recorded the computation time of DensePOLMM in step 2.

We carried out extensive simulations to investigate type I error rates and powers of POLMM approaches. We simulated genotypes of 10,000 subjects in 1,000 families on the basis of the pedigree shown in Figure S2, in which each family included 10 subjects. We performed gene-dropping simulations.22 First, we simulated a set of “pseudo” sequences, each of which included 10,000 independent variants. Then, we used these sequences as founder haplotypes that propagated through the pedigree of 10 family members. To construct the GRM for mixed model methods, we simulated 100,000 independent variants by using the same gene-dropping scheme with MAFs ranging from 0.05 to 0.5. The estimated kinship coefficients are shown in Figure S3. For subject , two covariates and were simulated following the standard normal distribution and a Bernoulli (0.5) distribution, respectively. Given the variance component , random effects were simulated following a multivariate normal distribution where is the GRM from the family structure. We followed Equation 1 to simulate ordinal categorical phenotypes by using linear predicator in which is the genotype value of one variant. We considered two common types of phenotypic distribution, bell-shaped distribution and L-shaped distribution (Figure S4), and selected cutpoints to correspond to the given phenotypic distribution. Under the null model , we considered three variance components 0.5, 1, and 2 to evaluate type I error rates at a significance level . For each phenotypic distribution, we simulated 100 datasets of phenotypes and covariates. We considered common, low-frequency, and rare variants with MAFs of 0.3, 0.01, and 0.005, respectively. For each MAF, we simulated variants. Thus, for each pair of phenotypic distribution and MAF, in total tests were performed. Under the alternative model , we considered the variance component and increased genetic effect size to evaluate empirical powers at a significance level . For each , we simulated 200 datasets including ordinal categorical phenotypes, covariates, and genotypes of one causal variant.

In addition to DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM, which use a hybrid of normal distribution approximation and SPA, we also evaluated DensePOLMM-NoSPA and FastPOLMM-NoSPA, both of which use normal distribution approximation to test all variants. We also evaluated some alternative methods, including SAIGE, fastGWA, and BOLT-LMM. For SAIGE, we dichotomized the categorical phenotypes (Figure S4). For fastGWA and BOLT-LMM, we treated the categorical phenotype as a quantitative trait from 1 to , where is the number of category levels.

To compare DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM, we added one scenario to simulate random effect vector . First, we randomly selected 50,000 variants (i.e., 50%) from the 100,000 variants that were used to estimate the GRM. Then, for subject , random effect , where , was the genotype of the -th selected variant, and was simulated following a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.085 so that the empirical variance of the random effects is close to . In this scenario, the random effects were strongly related to the estimated GRM used in the null mixed models fitting. We set variance components and 10 to simulate moderate and high heritability, respectively. Besides the bell-shaped phenotypic distribution, we also simulated phenotypes with five and ten evenly distributed categories.

We also simulated phenotypes by using real genotype data from white British participants in UK Biobank. We selected 152,951 subjects who participated the questionnaire of food (and other) preferences. Instead of simulating random effect by using a given family structure, we randomly selected common variants with MAFs > 0.05 in chromosomes 11–22 and then simulated random effect . We simulated following two distributions: (1) a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.085 and (2) a gamma distribution with a shape parameter of 1 and a scale parameter of 0.05. We considered three and simulated ordinal categorical phenotypes of four L-shaped distributions by using linear predicator .

In section C of the supplemental methods, we simulated ordinal categorical phenotypes following some alternative models, including adjacent category logistic model and stereotype model. The simulation results showed that POLMM approaches can still control type I error rates at a stringent significance level of even if the proportional odds ratio assumption is violated (Figure S5).

Application to UK Biobank data

We used FastPOLMM to conduct genome-wide analyses of 258 ordinal categorical phenotypes in the UK Biobank data of 408,961 white British participants. Most of the categorical phenotypes measured dietary, lifestyle and environment, and psychosocial factors (Table S2). We used 30 million Haplotype Reference Consortium23 (HRC)-imputed variants with minor allele counts 20 and imputation R2 greater than 0.3. More details on the quality control, genotyping, imputation, and principal components can be found elsewhere.6 We incorporated birth year, sex (if applicable), and top four principal components as covariates and used 340,447 high-quality SNPs to calculate the sparse GRM in which all off-diagonal elements less than 0.05 were set to 0.9,21

For phenotypes of food (and other) preferences, the values of phenotypes were collected from 2019 to 2020; for most of the other phenotypes, we only analyzed the values on the initial assessment visit (from 2006 to 2010). In addition, some phenotypes (e.g., comparative height size at age 10) are not based on the age to answer the questions. Hence, instead of using the age to answer the questions, we incorporated birth years as covariates in all the analyses. The subjects who did not participated in the survey or without meaningful values (e.g., “do not know” or “prefer not to answer”) were excluded from the analysis. For example, for the food (and other) preferences, which account for 150 of 258 phenotypes, 152,951 white British participants were analyzed. We have carefully examined the orders of different categories.

Results

Runtime and resource requirements

The computation time and memory usage of all five methods of fastGWA, BOLT-LMM, SAIGE, DensePOLMM, and FastPOLMM are presented in Figure S6 and Table S1. In step 1, to fit a null mixed model, fastGWA and FastPOLMM were much faster and required much less memory than the three methods using dense GRMs. BOLT-LMM, SAIGE, and DensePOLMM required comparable computation time and memory usage because they used the same optimized strategies to incorporate a dense GRM. SAIGE and DensePOLMM were slower than BOLT-LMM because both logistic and proportional odds models require more computation steps to adjust for covariates than linear models in step 1. DensePOLMM required more time than SAIGE when sample size was greater than 100,000. This is mainly because DensePOLMM used a block diagonal matrix as the preconditioner matrix for PCG, which took more iterations to converge than that in SAIGE given the same tolerance criterion. Interestingly, DensePOLMM was faster than SAIGE when the sample size was smaller than 40,000. This might be because we optimized C++ codes to read in genotypes for GRM construction. For POLMM methods, more computational time and slightly more memory usage were required when analyzing a phenotype with more category levels. For example, to fit a null mixed model with 397,798 subjects, if the number of levels is 3, DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM took 49.9 and 0.03 h, respectively; if the number of levels is 6, DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM took 64.2 and 0.09 h, respectively.

In step 2, we first recorded the computation time to analyze 340,447 markers and then projected them to a genome-wide analysis with 30 million markers. The genotype data were stored in BGEN format because UK Biobank uses it for the imputed data.24 BOLT-LMM and fastGWA were faster than POLMM and SAIGE methods, which is expected because logistic regression is more complicated than linear regression. POLMM is slightly faster than SAIGE. As the number of levels increased from 3 to 6, the computation time of POLMM methods slightly increased. Suppose that we use 24 CPU cores for parallel computation: POLMM methods require around 14.2 h for a genome-wide analysis including around 30 million markers.

False positive rate and statistical power

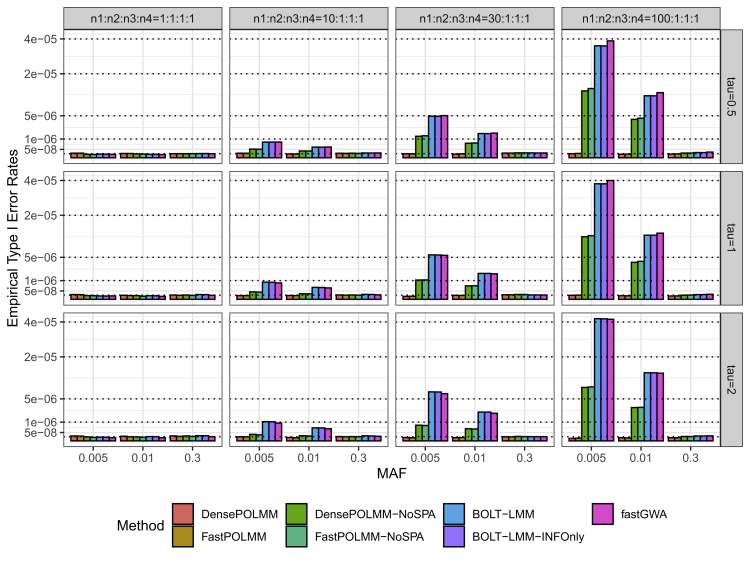

The simulation results showed that DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM methods can control type I error rates at a significance level of (Figures 1 and S7). Meanwhile, type I error rates of other methods were inflated when testing low-frequency and rare variants (MAF 0.01) and the phenotypic distribution was unbalanced. For example, when the variance component was and the sample size proportion in 4 levels was 100:1:1:1, to test low-frequency variants with a MAF of 0.01, the type I error rates of POLMM methods and the other methods were less than and greater than , respectively. Consistent for both bell-shaped and L-shaped phenotypic distributions, the results suggested that POLMM approaches can accurately account for ordinal categorical responses and using SPA is more accurate than using normal distribution. If we dichotomize the categorical phenotype, the POLMM is a logistic mixed model and it is expected that SAIGE can control type I error rates.9 Hence, we did not evaluate the empirical type I error rates of SAIGE.

Figure 1.

Empirical type I error rates of POLMM, BOLT-LMM, and fastGWA methods at a significance level 510−8

We simulated 1,000 families with a total sample size 10,000 and an ordinal categorical phenotype including four levels with sample sizes , , , and . From left to right, the plots consider four scenarios: balanced , moderately unbalanced , unbalanced , and extremely unbalanced . From top to bottom, the plots consider three variance components, tau, 0.5, 1, and 2. We simulated common, low-frequency, and rare variants with MAFs of 0.3, 0.01, and 0.005, respectively. In total, 109 replications were conducted in each scenario.

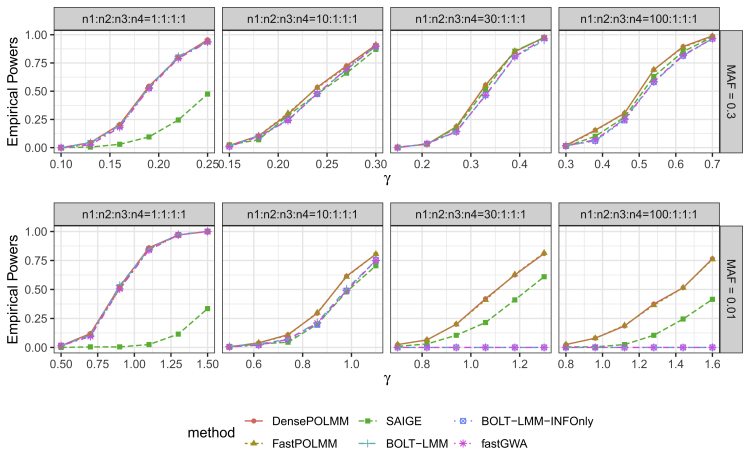

Next, we compared the empirical powers of POLMM methods, SAIGE, fastGWA, and BOLT-LMM at a significance level (Figures 2 and S8). Because fastGWA and BOLT-LMM cannot control type I error rates when the phenotypic distribution is unbalanced, we used empirical significance levels to evaluate powers. In all simulation scenarios, POLMM methods were the most powerful. When the phenotypic distribution is balanced, fastGWA and BOLT-LMM were similarly powerful as POLMM methods. However, when the phenotypic distribution is unbalanced, fastGWA and BOLT-LMM methods were less powerful than POLMM methods, especially when testing low-frequency variants with MAF = 0.01. Because the dichotomizing process would result in information loss, SAIGE was less powerful than POLMM methods. Figure S8 shows that different dichotomizing processes could result in significantly different powers for SAIGE.

Figure 2.

Empirical powers of POLMM, SAIGE, BOLT-LMM, and fastGWA methods at significance level 510−8

We simulated 1,000 families with a total sample size 10,000 and an ordinal categorical phenotype including four levels with sample sizes , , , and . From left to right, the plots consider four scenarios: balanced , moderately unbalanced , unbalanced , and extremely unbalanced . From top to bottom, the plots consider two MAFs of 0.3 and 0.01 to simulate common and low-frequency variants. We let the variance component . For SAIGE, we dichotomize phenotype as 0 or 1 depending on whether the subject is in level 1 or not. For BOLT-LMM, the empirical powers were calculated on the basis of the empirical significance levels because it cannot control type I error rates for low-frequency variants.

Figures S9–S12 show the results of FastPOLMM when phenotypes were simulated with real genotypes. Because parts of genetic variants in chromosomes 11–22 are causal variants, we separately demonstrated the p value results of genetic variants in chromosomes 1–10 and chromosomes 11–22. From Figures S9 and S11, we can see POLMM methods can control type I error rates for various phenotypic distributions. On the other hand, from Figures S10 and S12, a large number of genetic variants in chromosomes 11–22 were identified. This is expected because we simulated the ordinal categorical phenotypes by using real data of variants in these chromosomes.

Comparison between DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM methods

Figures S13–S16 present the variance component estimation and the empirical powers of POLMM methods. The estimation of DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM, both of which deviated from true , were slightly different, especially when the true was large. The biased estimation has been widely discussed in other studies using penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL).9 Interestingly, the estimation increased and tended to the true as the number of levels increased from 3 to 10. This might be because more levels give more information, which results in a more accurate estimation of the variance component . In most scenarios, the empirical powers of DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM were similar, and the largest difference was less than 2.5%. Only when SNPs used to construct the GRM were significantly associated with the phenotype (e.g., liability heritability = ) and the number of levels is large (e.g., 10), DensePOLMM is more powerful than FastPOLMM by no more than 4.67% and 7.51% when testing SNPs with MAF = 0.3 and 0.01, respectively. This may be because only when the number of levels is large, accounting for the polygenic effects through a dense GRM can substantially improve the power. Note that in this simulation, we simulated SNPs for the dense GRM independently from the SNPs to test to prevent proximal contamination.

Compared to DensePOLMM, FastPOLMM can give a substantial improvement in terms of computation time and memory usage while only suffering a limited loss of power in restricted simulation scenarios. Hence, we recommend using FastPOLMM, especially when analyzing a large-scale dataset with sample size greater than 200,000.

Application to UK Biobank data

We used FastPOLMM to conduct genome-wide analyses of 30 million SNPs in the UK Biobank data of 408,961 samples from white British participants. We analyzed 258 ordinal categorical phenotypes, most of which measured dietary, lifestyle and environment, and psychosocial factors (Table S2). All analysis results are publicly available through a visual server. The web interface provides intuitive visualizations at three levels of granularity: genome-wide summaries at the trait level and regional (LocusZoom)16 and phenome-wide summaries at the variant level.2

We used PLINK25 to conduct clumping analysis for the variants with a p value less than (window size of 5 Mb and linkage disequilibrium threshold of 0.1). For these 258 phenotypes, we identified 5,885 clumped distinct genome-wide significant variants, of which, 424 variants (7.2%) are low-frequency variants with MAF < 0.01. We used ANNOVAR26 to functionally annotate these genome-wide significant variants. In total, 275 clumped variants are in exon region, of which, 207 (75.3%, binomial test p value: 1.04 × 10−12) variants are nonsynonymous variants. On the basis of the PolyPhen2 HDIV score, a score to predict functional effect via HumDiv training set,27 63 nonsynonymous variants (30.4%, binomial test p value: 0.506) are probably damaging (score 0.957) and 33 nonsynonymous variants (15.9%, binomial test p value: 1) are possibly damaging (score 0.453). Table S3 summarizes the functional annotation of more than 24 million SNPs in which the proportion of nonsynonymous variants, probably damaging variants, and possibly damaging variants was calculated.

We highlighted some nonsynonymous significant low-frequency variants with MAF < 0.01. For the phenotype of “morning/evening person” (UK Biobank field ID: 1180), we identified an association of a nonsynonymous SNP rs139315125 (MAF: 0.47%, p value: 5.3 × 10−21, gene: PER3 [MIM: 603427], PolyPhen2 HDIV score: 0.998, see Figure S17 for more details). Subjects who tend to sleep and wake up early have a higher frequency of minor allele G. PER3 is a core component of the circadian clock and the association between this SNP and sleep-wake patterns has been reported in previous studies.28 For the phenotype of “use of sun/UV protection” (UK Biobank field ID: 2267), we identified a nonsynonymous SNP rs121918166 (MAF: 0.9%, p value: 5.2 × 10−31, gene: OCA2 [MIM: 611409], PolyPhen2 HDIV score: 1, see Figure S18 for more details). Subjects who use sun/UV protection more frequently have a higher frequency of minor allele T. OCA2 is involved in mammalian pigmentation and this SNP has been previously associated with human eye color and melanoma.29, 30, 31 Other interesting associations include the phenotype of “comparative height size at age 10” (UK Biobank field ID: 1697) and rs78727187 (MAF: 0.6%, p value: 5.1 × 10−19, gene: FBN2 [MIM: 612570], PolyPhen2 HDIV score: 0.818), rs117116488 (MAF: 0.99%, p value: 1.4 × 10−18, gene: ACAN [MIM: 155760], PolyPhen2 HDIV score: 0.993), and rs112892337 (MAF: 0.4%, p value: 3.0 × 10−15, gene: ZFAT [MIM: 610931], PolyPhen2 HDIV score: 1) and the phenotype of “relative age of first facial hair” (UK Biobank field ID: 2375) and rs138800983 (MAF: 0.3%, p value: 8.4 × 10−10, gene: KRT75 [MIM: 609025], PolyPhen2 HDIV score: 0.969).

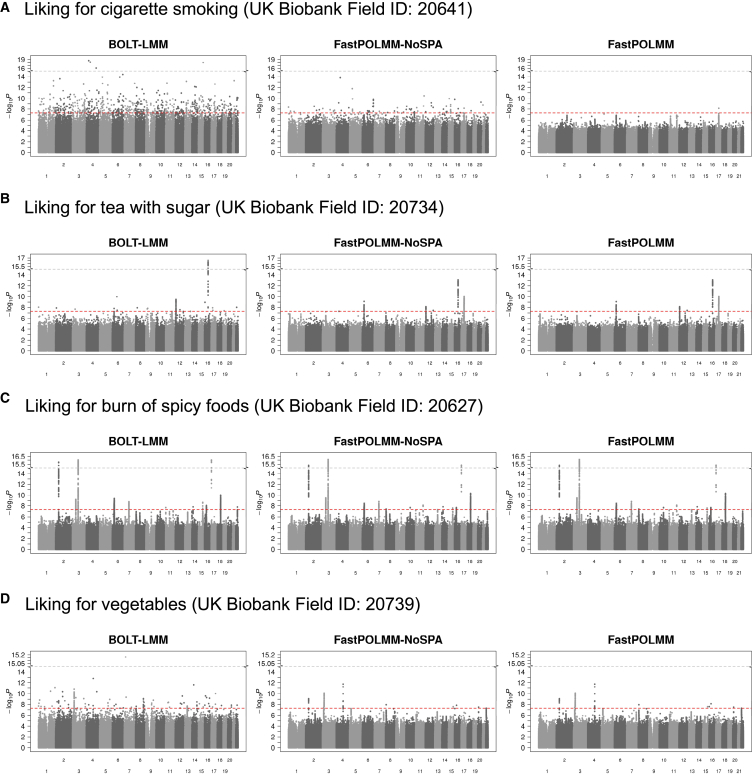

In addition, we selected four food preferences with different sample size distributions as phenotypes to compare BOLT-LMM and FastPOLMM in UK Biobank data analysis (Figure S19). The preferences were encoded from 1 (extremely dislike) to 9 (extremely like). For BOLT-LMM, we treated the phenotypes as quantitative traits and incorporated the same set of covariates and GRM as in FastPOLMM. Figures 3 and S20 present the Manhattan and QQ plots of the analysis results. When the phenotypic distribution is balanced, BOLT-LMM performed similarly to FastPOLMM. However, in other cases, BOLT-LMM could inflate type I error rates, especially when testing low-frequency and rare variants with MAF < 0.01. FastPOLMM-NoSPA was better than BOLT-LMM but still cannot control type I error rates at a genome-wide significance level, which suggests that the proportional odds logistic model and SPA both contribute to more accurate association tests. All the real data analysis results were consistent with the simulation results, which indicate that using linear models is not an ideal solution in ordinal categorical data analysis, especially when testing low-frequency variants.

Figure 3.

Manhattan plots for UK Biobank data analysis

The left panels show Manhattan plots based on BOLT-LMM, the middle panels show Manhattan plots based on FastPOLMM-NoSPA, and the right panels show Manhattan plots based on FastPOLMM. The redline represents the genome-wide significance level 5.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a scalable and accurate genetic association analysis tool, POLMM, for ordinal categorical data analysis in a large-scale dataset with hundreds of thousands of samples. The tool can accurately account for the dependence of an ordinal categorical phenotype on covariates. Two closely related methods, DensePOLMM and FastPOLMM, were proposed to use dense and sparse GRMs to adjust for the sample relatedness, respectively. DensePOLMM uses similar optimized strategies as in SAIGE and BOLT-LMM, which makes it scalable to incorporate a dense GRM into the mixed model. However, as the sample size increases, DensePOLMM is still computationally expensive. On the other hand, FastPOLMM is more computationally efficient. Extensive simulations demonstrate that FastPOLMM is as reliable as DensePOLMM and only suffers a small amount of power loss in limited simulation scenarios. Hence, if the sample size is greater than 500,000 and hundreds of GWASs are required for a phenome-wide analysis, we recommend using FastPOLMM.

We compared our method POLMM with two commonly used strategies: (1) dichotomizing the categorical phenotype and then using SAIGE9 and (2) treating the categorical phenotype as a quantitative trait and then using BOLT-LMM11 and fastGWA.12 The dichotomizing process combined multiple levels into one group, which could lose useful phenotypic information and statistical power. On the other hand, treating the categorical phenotypes as a quantitative trait violates the nature of the ordinal categorical phenotype, which could result in inflated type I error rates and power loss. Through simulation studies and real data analysis, unless the phenotypic distribution is unbalanced, the linear mixed model approaches are still reliable when testing common variants, which suggests that fastGWA analyses limited to SNPs with MAF > 0.01 should still be valid for many of the phenotypes, whereas for low-frequency or rare variants, the linear mixed model approaches might be not valid anymore. The reliability of the linear mixed model approaches on categorical phenotypes greatly depends on the minor allele counts in the less common categories, which is relevant to both phenotypic distribution and the MAF of the marker. Considering the diversity of the phenotypic distribution, the arbitrary MAF cutoff of 0.01 still cannot ensure the results are well calibrated. In addition, we identified many phenotypes associated variants with MAF < 0.01 in the UK Biobank data analysis that were missed in the fastGWA analyses.

We applied the FastPOLMM to analyze 258 ordinal categorical phenotypes on UK Biobank, of which, 150 phenotypes are food and other preferences (UK Biobank category 1039). The preference data (v.1.1) were released in January 2020. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that GWASs were applied to analyze the preference data. All analyses results have been made publicly available through a visual server. The web interface provides intuitive visualizations and is a useful resource for post-GWAS analyses. In this paper, we focus more on the development and the evaluation of the new POLMM methods. The UK Biobank data analysis has demonstrated the validity and reliability of the new methods on large-scale biobank categorical data analysis. More detailed explorations about the data analysis results are left to researchers with expertise in psychology, dietetics, etc.

There are several limitations in POLMM, most of which are similar to those in SAIGE and other mixed model approaches. First, DensePOLMM is still computationally expensive when fitting a null mixed model with sample size greater than 500,000. Second, POLMM assumes an infinitesimal architecture; that is, the effect sizes of genetic markers are normally distributed. If the genetic architecture is non-infinitesimal, POLMM methods may sacrifice power. Third, the variance component estimate is biased and should not be used to estimate heritability. Interestingly, we observe a more accurate estimate as the number of categories increases. Fourth, POLMM is based on a proportional odds model, which is not applicable to analyze unordered categorical response variables.

In the future, we plan to extend the current single-variant test to gene- or region-based multiple variants tests to better identify the rare variants. Recently, a machine learning method called REGENIE was proposed for quantitative and binary traits analysis. Instead of using a mixed effect model, REGENIE32 uses a ridge regression model to account for polygenic effects. We plan to evaluate the strategies in REGENIE in ordinal categorical data analysis to extend POLMM. POLMM approaches are motivated to analyze large-scale biobank data collected following a cohort study design. Suppose that data are collected from a matched case-control study design, the stratified sampling for different levels could inflate the parameter estimation and genetic association testing.33 We plan to extend the POLMM approaches to deal with the effect of the sampling. Similar to SAIGE, POLMM methods estimate odds ratios for genetic markers (supplemental methods, section A) by using the parameter estimates from the null model and might not be accurate. We plan to propose more accurate estimation by using Firth’s correction on categorical data analysis.

Ordinal categorical phenotypes are widely observed in surveys, questionnaires, and testing to measure human behaviors, satisfaction, and preferences. However, because of the lack of analysis tools, methods designed for binary and quantitative traits have been used to analyze the categorical data, which is inappropriate and can result in suspicious results. Our method, POLMM, provides an accurate and scalable solution with the following features: can accurately model the ordinal categorical data by using a proportional odds logistic model, can adjust for sample relatedness by incorporating random effects, can be scalable to analyze a large-scale dataset with hundreds of thousands of subjects, and can test low-frequency variants under unbalanced phenotypic distribution by using SPA to approximate the null distribution of the test statistics. Because of all these features, POLMM is the only available unified approach for ordinal categorical data analysis in biobanks and large cohort studies.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R01-HG008773 (W.B. and S.L.) and the Brain Pool Plus Program (BP+, Brain Pool+) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2020H1D3A2A03100666, S.L.). UK Biobank data were accessed under the accession number UKB: 45227.

Published: April 8, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.03.019.

Contributor Information

Wenjian Bi, Email: wenjianb@umich.edu.

Seunggeun Lee, Email: lee7801@snu.ac.kr.

Appendix A: Maximum likelihood estimation of POLMM

The maximum likelihood function and its derivatives

The first partial derivative of with respect to the linear predicator is

The second and fourth equations hold since and The first derivative of log-likelihood function with respect to is

and the first derivatives of with respect to are

where the definitions of matrix , and vectors of and have been given in the main text. Under certain regularity conditions,34 the second derivative of with respect to can be approximated by

Estimation of fixed covariates effects and random effects

Similar to GMMAT,7 we use Laplace’s method to approximate the -dimensional integral, and the marginal log-likelihood function becomes the following penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL)35

| (Equation A1) |

where

and the second derivative

Following GMMAT7 and SAIGE,9 we assume that matrix and change slowly with respect to . The derivatives of Equation A1 with respect to are

Under the null hypothesis , if and are known, we jointly choose and to maximize , then because maximizes for given .7 Defining a working vector , the solution of

can be written as the solution to the system

Let , , and , then

| (Equation A2) |

is the solution. We note that

Estimation of variance component parameters

Given random effect , vector has a mean of and a covariance matrix of . Using quasi-likelihood and Pearson chi-square statistics,35 we approximate the log-likelihood

where is independent from random vector . Then, the log-likelihood function

The restricted maximum likelihood (REML) version7 is

Because , the derivative

and the average information matrix, , is as below:

Using AI-REML algorithm, we avoid the evaluation of the traces of large matrices that appear in both the expected and observed (REML) information matrices.36

Workflow of the model fitting algorithm

We add one intercept term with all elements of 1 to the covariate matrix and fix the first cutpoint . Then, after updating and , we use the Newton-Raphson method to iteratively estimate cutpoints until convergence.

We use the following workflow to fit the null POLMM:

-

(1)

fit a proportional odds logistic model with and to estimate , and then calculate ; set initial value ;

-

(2)

update and by using and ;

-

(2.1)

update following Equation A2;

-

(2.2)

use the Newton-Raphson algorithm to update until converges;

-

(2.3)

repeat steps 2.1 and 2.2 until converges;

-

(3)

update and by using and ;

-

(4)

repeat steps 2–3 until converges.

Appendix B: Score test and saddlepoint approximation

Under the null hypothesis, the score statistic

Because , its estimated variance is

For each variant, the variance-adjusted test statistic is

which has mean zero and variance one under the null hypothesis. Because the statistic

and follows a Berounlli distribution, the CGF of is

and its derivatives

We use to approximate the CGF of such that the variance from CGF is 1; that is,

where

After fitting the null model, we calculate and store the following matrix:

For each variant, it takes computations to calculate vector . Because is a diagonal matrix, it takes to calculate the score statistic and the variance . Thus, for normal distribution approximation, the computational complexity is still and does not increase as the number of category levels increases. For SPA, we use a partially normal approximation method to speed up the computation.8 Suppose that the first subjects have at least one minor allele each and the rest have homozygous major genotypes. We can express

where and . Let , and let be the th element of . Then, we can further express as

where

If we assume that the non-genetic covariates are relatively balanced in the sample, then the normal approximation should be a good approximation of the null distribution of each . Because is a weighted sum of the variables, we can also approximate the null distribution of by using a normal distribution and the CGF of can be approximated by

where

and . Hence, with the partially normal approximation, the CGF of is , and the SPA takes computations to calculate the CGF and its derivatives.

Data and code availability

The summary statistics and PheWeb with quantile-quantile plots, Manhattan plots, and regional association plots for 258 categorical phenotypes in the UK Biobank by POLMM are available for public download (see web resources). POLMM is implemented as an open-source R package (see web resources).

Web resources

ANNOVAR (April 16, 2018), https://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/

BOLT-LMM (v.2.3.4), https://alkesgroup.broadinstitute.org/BOLT-LMM

fastGWA (GCTA, v.1.93.1beta), https://cnsgenomics.com/software/gcta/#fastGWA

POLMM (v.0.2.2), https://github.com/WenjianBI/POLMM

RcppParallel, http://rcppcore.github.io/RcppParallel/

SAIGE (v.0.36.3), https://github.com/weizhouUMICH/SAIGE

UK Biobank PheWeb and analysis results, https://polmm.leelabsg.org/

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Beesley L.J., Salvatore M., Fritsche L.G., Pandit A., Rao A., Brummett C., Willer C.J., Lisabeth L.D., Mukherjee B. The emerging landscape of health research based on biobanks linked to electronic health records: Existing resources, statistical challenges, and potential opportunities. Stat. Med. 2019;39:773–800. doi: 10.1002/sim.8445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gagliano Taliun S.A., VandeHaar P., Boughton A.P., Welch R.P., Taliun D., Schmidt E.M., Zhou W., Nielsen J.B., Willer C.J., Lee S. Exploring and visualizing large-scale genetic associations by using PheWeb. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:550–552. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0622-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane J.M., Jones S.E., Dashti H.S., Wood A.R., Aragam K.G., van Hees V.T., Strand L.B., Winsvold B.S., Wang H., Bowden J., HUNT All In Sleep Biological and clinical insights from genetics of insomnia symptoms. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:387–393. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0361-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agresti A. John Wiley & Sons; 2003. Categorical data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhulst B., Maes H.H., Neale M.C. GW-SEM: A Statistical Package to Conduct Genome-Wide Structural Equation Modeling. Behav. Genet. 2017;47:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s10519-017-9842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., Band G., Elliott L.T., Sharp K., Motyer A., Vukcevic D., Delaneau O., O’Connell J. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H., Wang C., Conomos M.P., Stilp A.M., Li Z., Sofer T., Szpiro A.A., Chen W., Brehm J.M., Celedón J.C. Control for Population Structure and Relatedness for Binary Traits in Genetic Association Studies via Logistic Mixed Models. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:653–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dey R., Schmidt E.M., Abecasis G.R., Lee S. A Fast and Accurate Algorithm to Test for Binary Phenotypes and Its Application to PheWAS. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou W., Nielsen J.B., Fritsche L.G., Dey R., Gabrielsen M.E., Wolford B.N., LeFaive J., VandeHaar P., Gagliano S.A., Gifford A. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1335–1341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou X., Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:821–824. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loh P.R., Tucker G., Bulik-Sullivan B.K., Vilhjálmsson B.J., Finucane H.K., Salem R.M., Chasman D.I., Ridker P.M., Neale B.M., Berger B. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:284–290. doi: 10.1038/ng.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang L., Zheng Z., Qi T., Kemper K.E., Wray N.R., Visscher P.M., Yang J. Nature Publishing Group; 2019. A resource-efficient tool for mixed model association analysis of large-scale data. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Z., Bi W., Zhou W., VandeHaar P., Fritsche L.G., Lee S. UK Biobank Whole-Exome Sequence Binary Phenome Analysis with Robust Region-Based Rare-Variant Test. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;106:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou W., Zhao Z., Nielsen J.B., Fritsche L.G., LeFaive J., Gagliano Taliun S.A., Bi W., Gabrielsen M.E., Daly M.J., Neale B.M. Scalable generalized linear mixed model for region-based association tests in large biobanks and cohorts. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:634–639. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0621-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bi W., Zhao Z., Dey R., Fritsche L.G., Mukherjee B., Lee S. A Fast and Accurate Method for Genome-wide Scale Phenome-wide G × E Analysis and Its Application to UK Biobank. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;105:1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pruim R.J., Welch R.P., Sanna S., Teslovich T.M., Chines P.S., Gliedt T.P., Boehnke M., Abecasis G.R., Willer C.J. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtbrügge W., Schumacher M. A comparison of regression models for the analysis of ordered categorical data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 1991;40:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilmour A.R., Anderson R.D., Rae A.L. The Analysis of Binomial Data by a Generalized Linear Mixed Model. Biometrika. 1985;72:593–599. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin X., Breslow N.E. Bias Correction in Generalized Linear Mixed Models With Multiple Components of Dispersion. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1996;91:1007–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchinson M.F. A stochastic estimator of the trace of the influence matrix for laplacian smoothing splines. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 1990;19:433–450. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J., Lee S.H., Goddard M.E., Visscher P.M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abecasis G.R., Cherny S.S., Cookson W.O., Cardon L.R. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy S., Das S., Kretzschmar W., Delaneau O., Wood A.R., Teumer A., Kang H.M., Fuchsberger C., Danecek P., Sharp K., Haplotype Reference Consortium A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1279–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Band G., Marchini J. BGEN: a binary file format for imputed genotype and haplotype data. bioRxiv. 2018 doi: 10.1101/308296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier L.C.A.M., Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M., Lee J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adzhubei I., Jordan D.M., Sunyaev S.R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2013;Chapter 7:20. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L., Hirano A., Hsu P.-K., Jones C.R., Sakai N., Okuro M., McMahon T., Yamazaki M., Xu Y., Saigoh N. A PERIOD3 variant causes a circadian phenotype and is associated with a seasonal mood trait. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E1536–E1544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600039113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffy D.L., Box N.F., Chen W., Palmer J.S., Montgomery G.W., James M.R., Hayward N.K., Martin N.G., Sturm R.A. Interactive effects of MC1R and OCA2 on melanoma risk phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:447–461. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford N.G., Kelly D.E., Hansen M.E.B., Beltrame M.H., Fan S., Bowman S.L., Jewett E., Ranciaro A., Thompson S., Lo Y., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Loci associated with skin pigmentation identified in African populations. Science. 2017;358:eaan8433. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen J.D., Pietroni C., Johansen P., Andersen M.M., Pereira V., Børsting C., Morling N. Importance of nonsynonymous OCA2 variants in human eye color prediction. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2016;4:420–430. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mbatchou J., Barnard L., Backman J., Marcketta A., Kosmicki J.A., Ziyatdinov A., Benner C., O’Dushlaine C., Barber M., Boutkov B. Computationally efficient whole genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.19.162354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukherjee B., Liu I., Sinha S. Analysis of matched case-control data with multiple ordered disease states: possible choices and comparisons. Stat. Med. 2007;26:3240–3257. doi: 10.1002/sim.2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casella G., Berger R.L. Duxbury Pacific Grove; CA: 2002. Statistical inference. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breslow N.E., Clayton D.G. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilmour A.R., Thompson R., Cullis B.R. Average Information REML: An Efficient Algorithm for Variance Parameter Estimation in Linear Mixed Models. Biometrics. 1995;51:1440–1450. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The summary statistics and PheWeb with quantile-quantile plots, Manhattan plots, and regional association plots for 258 categorical phenotypes in the UK Biobank by POLMM are available for public download (see web resources). POLMM is implemented as an open-source R package (see web resources).