Abstract

By improving resource quality, cross-ecosystem nutrient subsidies may boost demographic rates of consumers in recipient ecosystems, which in turn can affect population and community dynamics. However, empirical studies on how nutrient subsidies simultaneously affect multiple demographic rates are lacking, in part because humans have disrupted the majority of these natural flows. Here, we compare the demographics of a sex-changing parrotfish (Chlorurus sordidus) between reefs where cross-ecosystem nutrients provided by seabirds are available versus nearby reefs where invasive, predatory rats have removed seabird populations. For this functionally important species, we found evidence for a trade-off between investing in growth and fecundity, with parrotfish around rat-free islands with many seabirds exhibiting 35% faster growth, but 21% lower size-based fecundity, than those around rat-infested islands with few seabirds. Although there were no concurrent differences in population-level density or biomass, overall mean body size was 16% larger around rat-free islands. Because the functional significance of parrotfish as grazers and bioeroders increases non-linearly with size, the increased growth rates and body sizes around rat-free islands likely contributes to higher ecosystem function on coral reefs that receive natural nutrient subsidies. More broadly, these results demonstrate additional benefits, and potential trade-offs, of restoring natural nutrient pathways for recipient ecosystems.

Subject terms: Ecology, Marine biology, Ichthyology, Ecology, Conservation biology, Ecosystem ecology, Invasive species, Population dynamics, Stable isotope analysis

Introduction

Energy acquisition and allocation strategies vary across populations due to a variety of biotic and environmental factors, resulting in intraspecific variation in demographic rates over a range of spatial scales1–6. Understanding the drivers and consequences of these differences in individual demographic rates provides a key link to population and community dynamics7,8, and can be used to identify areas of high conservation priority, for example hotspots of enhanced growth and reproduction9.

Many ecosystems receive allochthonous nutrient inputs via the movement of mobile consumers, which in turn can boost the availability and quality of food resources10,11. With higher resource acquisition, trade-offs in energy allocation can be reduced, thus boosting multiple demographic rates12–14. Humans are disrupting the flow of natural nutrient subsidies, however, through activities such as overharvesting, habitat degradation, and the introduction of exotic predators11. For example, seabirds transport large quantities of nutrients from offshore pelagic food webs to terrestrial and coastal systems by feeding in the open ocean and returning to islands where they roost and breed10,15. However, introduced rats feed on nesting seabirds, chicks, and eggs, and have consequently decimated seabird populations in 90% of the world’s island chains16. Despite the importance of cross-system nutrient subsidies10,11, it is unclear how their loss influences multiple demographic rates in consumers, and how this in turn influences population dynamics and ecosystem functioning.

On nearshore coral reefs, the importance of breeding seabirds in providing natural nitrogen inputs, and thus bolstering fish biomass, productivity, and ecosystem functioning, has been recently recognized17,18. This includes evidence that a small species of herbivorous damselfish grows faster around islands with abundant seabird populations compared to islands with invasive rats and thus few seabirds17. These damselfish consume turf algae within small territories, and elevated levels of seabird-derived nutrients are present in both turf algae and damselfish tissues, providing a causative pathway between seabird presence and enhanced fish growth rates17. However, it is unknown whether seabird-derived nutrients affect the growth of larger species that perform key functions on coral reefs, such as parrotfishes. Parrotfishes primarily consume microscopic autotrophs, namely cyanobacteria on and within the reef matrix, which they access with their powerful beak-like jaws19,20. In doing so, they perform several ecosystem functions, including scraping the substrate clear of algae and bioeroding dead reef substrate, thus producing and transporting sediment21. Importantly, the functional significance of parrotfishes scales non-linearly with body size22–25, providing a direct link between individual growth rates and ecosystem function.

Whether seabird-derived nutrients affect the reproductive investment of coral-reef fish is currently unknown. Like most benthic marine organisms, local populations of coral-reef fish are linked via a dispersive larval phase, meaning there could be far-reaching effects of seabird-derived nutrients beyond the spatial scale of the subsidy itself. For example, if fish reproductive output is greater around islands with seabirds than islands with invasive rats, then these fish could serve as source populations for other reefs, much as populations within marine protected areas seed adjacent reefs26. Thus, studying the simultaneous effects of nutrient subsidies on growth and reproduction of reef fishes will not only determine their influence on life-history trade-offs, but could also inform our understanding of the spatial extent of nutrient effects.

Here, we test the influence of nutrient subsidies from seabirds on the demographic rates of the widespread and functionally-important parrotfish Chlorurus sordidus. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that seabirds increase the growth and reproductive investment of C. sordidus by comparing parrotfish around rat-free islands with high densities of breeding seabirds to those around nearby rat-infested islands with few seabirds. Using visual survey data, we then determine whether changes in these demographic rates coincide with population-level attributes (density, biomass, and size distribution) on reefs adjacent to rat-free versus rat-infested islands. We expect increased growth rates to enhance overall parrotfish biomass and size distributions, whereas density could be a driver of demographic differences due to density-dependent competition or predation. Finally, we examine other potential bottom-up and top-down drivers of demographic variation, focusing on nitrogen (a key nutrient) in parrotfish tissue and piscivorous fish populations.

Methods

Study sites, collections, and surveys

This study was conducted in the remote northern atolls of the Chagos Archipelago, Indian Ocean. Due to its status as a large (550,000 km2) marine protected area and its relative isolation, there is no fishing allowed or other direct human influences in the study atolls27–29. The Chagos Archipelago is also home to eighteen species of breeding seabirds, many of which are present in globally-significant numbers, leading to the designation of several Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) within the archipelago30. However, the distribution of seabirds throughout the archipelago is patchy due to the presence of black rats (Rattus rattus) on some islands, which were introduced several hundred years ago31. As a result of rat predation, seabird density is an estimated 760 times greater on rat-free islands than rat-infested islands, which in turn leads to ~ 251 times greater nitrogen input by seabirds to these islands and enhanced seabird-derived nutrients in sponges, algae, and herbivorous damselfish on adjacent coral reefs17. Seabird-derived nutrients likely enter the marine environment throughout the year, with both high rainfall and breeding seabirds occurring in every month30,32. In contrast to seabirds, which import nutrients from highly productive, offshore, open ocean areas17, invasive rats recycle nutrients that are already present on the islands. Thus, seabirds, but not rats, add substantial amounts of allochthonous nitrogen to islands and nearshore reefs.

For the specific islands used in this study, we obtained data on the densities of breeding seabirds from30, sea surface temperature from NOAA, wave exposure from33,34, and net primary productivity from34 (see Supplementary Table S1 for details). The presence versus absence of invasive rats, and thus seabirds, was the greatest difference among islands (Results, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). Sea surface temperature was similar across all of the islands, and although there was some atoll-level variation in wave exposure and net primary productivity, there were no consistent differences between rat-free versus rat-infested islands (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). Rat-free islands tended to be smaller than rat-infested islands, but island size is not expected to be a strong driver of parrotfish demography, especially across the range of island sizes investigated here (all < 244 ha). Therefore, we used the large differences in seabird-derived nutrient subsidies between islands with and without rats to test how nutrient inputs from seabirds affect the demography of parrotfish.

Bullethead parrotfish (C. sordidus) provide an ideal model with which to study the influence of nutrient subsidies on growth and reproduction for several reasons. Like most wrasses and parrotfishes, C. sordidus is a protogynous hermaphrodite, with distinct colouration patterns for each phase (immature, female [initial phase], and male [terminal phase], with rare occurrence of initial phase primary males35). Although the spawning frequency of C. sordidus is unknown, its sister species in the Pacific (C. spilurus, formerly C. sordidus) has an extended spawning season and can spawn throughout the lunar cycle36. Combined, these characteristics increased our likelihood of capturing spawning-capable females. Their high dispersal ability as larvae means there is little genetic separation at small to medium scales37, so any observed differences among individuals from different islands are likely to be driven by local differences in environmental conditions (e.g., seabird/rat presence) rather than genetic differences. Adults have relatively small home ranges (maximum linear distance 1.2 km along continuous reefs) and are unlikely to cross sand channels or move among reefs4,26,38, so we can assume individuals spend most of their time near where they were caught.

We haphazardly collected C. sordidus displaying initial phase colouration from shallow coral reefs on the lagoonal sides of 8 islands (4 rat-infested and 4 rat-free) from 4 to 16 March 2019 (n = 7–17 individuals per island, Supplementary Fig. S1). Although it is likely that C. sordidus spawns throughout the lunar cycle, to control for any temporal variation in reproductive investment we paired collections of fish from both rat-free and rat-infested islands within each of 3 atolls. Thus, all fish from Peros Banhos atoll were collected within 5 days (2 rat-free and 2 rat-infested islands, within 3 days of the new moon), fish from Salomon atoll were collected within 1 day (1 rat-free and 1 rat-infested island, 4 days after the new moon), and fish from the Great Chagos Bank were collected within 3 days (1 rat-free and 1 rat-infested island, 8–10 days after the new moon). Available information from this species and sister species C. spilurus suggests a high frequency of spawning activity throughout the lunar period, resulting in a temporally consistent gonad state (B. Taylor, unpublished data)36. All fish were caught from the reef crest and shallow slope within approximately 250 m from shore, where the signals from island-based nutrients are strongest17. Importantly, the habitats where we collected fish were similar across all islands; they were all sheltered, lagoonal reefs. All sampling was done in accordance with institutional and local guidelines, with ethical approval granted by the Lancaster University Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (AWERB permit number A100143).

For all fish, we measured total length (TL, cm) and wet weight (WW, kg) (size range = 14.0 to 26.8 cm TL and 0.05 to 0.39 kg WW). A sample of white dorsal muscle was taken and dried in an oven at 60˚C for 48 h for stable isotope analysis. Otoliths were removed and stored dry for aging analysis. Sex was determined by macroscopic examination of the gonads, and for fish identified as female, reproductive stage was classified as in39, and gonads were removed for further analysis. Gonads were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and then transferred to 70% ethanol for storage before histological analysis. We collected and identified 98 spawning capable (i.e., mature or ripe) females, 3 immature individuals, 2 transitional individuals, 1 initial phase male, and 11 regenerating (i.e., resting or inactive but mature) females.

To determine the population-level characteristics of parrotfish, we conducted underwater visual censuses around 10 islands (5 rat-infested and 5 rat-free) in May 2018 and 1 rat-infested island in March 2019, with five of these survey sites matching the collection sites (Supplementary Fig. S1). We conducted surveys and collections as close in time and space as possible, with surveys always conducted prior to the collections. Although logistical constraints prevented conducting all surveys and collections in the same year, several lines of evidence suggest that it is appropriate to interpret the results from the collections and surveys in tandem. First, herbivore populations have remained stable on these reefs from 2015 to 201840, and no major disturbances occurred between the majority of surveys (2018) and the majority of collections (2019). In addition, all of the parrotfish collected were at least 1 year of age (see Results), meaning that they were inhabiting the reefs at the time of the population surveys.

Fish were counted along four replicate 30-m transects, spaced 10 m apart, near the reef crest on the lagoon-side of each island (within approximately 325 m from shore), which matches the locations of the fish collections. Along each transect, one observer (NAJG) counted and estimated the size (TL, to the nearest cm) of all diurnal non-cryptic fishes > 8 cm TL, including C. sordidus, within a 5-m wide belt. Biomass was calculated using published length–weight relationships41. The surveys provide an aggregate picture of the population density, biomass, and size structure of C. sordidus on these reefs, as the colouration (immature, initial phase, or terminal phase) of individuals was not recorded. From the same surveys, we also gathered data on other factors that could influence parrotfish demography. Specifically, we estimated the density, biomass, and size structure of piscivorous fishes using the methods as for C. sordidus. We estimated hard coral cover using the point-intercept method, as coral cover is negatively related to parrotfish food availability20,42. Finally, we determined structural complexity using a standard scale ranging from 0 (no relief) to 5 (exceptionally complex relief)43,44. Data on piscivore biomass, coral cover, and structural complexity is previously published in40.

Laboratory analyses

To determine nutrient subsidy signals in the parrotfish, we quantified total nitrogen (%) and ratio of isotopic δ15N in dorsal muscle tissue from each parrotfish. Elevated δ15N values reflect seabird-derived nitrogen in nearshore tropical marine food chains, as seabird guano is high in δ15N in part because they feed on high trophic levels in the open ocean17,45,46. Analyses were conducted at the stable isotope facility at Lancaster University (Lancaster, UK). All samples were combusted using an Elementar Vario Micro Cube Elemental Analyser and analysed using an Isoprime 100 Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer, with international standards IAEA 600 and USGS 41. Accuracy based on internal standards was within 0.2 permil standard deviation. Selected samples were run in duplicate to further ensure accuracy of readings.

Parrotfish otoliths were cross-sectioned to determine age (in years) from annual bands for all individuals. One randomly selected otolith from each pair was mounted to the edge of a glass slide using thermoplastic glue (Crystalbond 509) with the otolith core situated directly inside the slide edge. The otolith material was sanded away to the slide edge using a 1200-grit diamond lap on a lapping machine with constant water flow. The slide was heated (200 °C) and remounted with the newly sanded surface placed flat against the slide, and then the remaining bulk of otolith material was sanded away until a thin transverse cross-section (150 µm) remained. Annuli, denoted by alternating opaque and translucent growth bands, were counted using a stereo-microscope three separate times by the same observer, who was blinded to any characteristics of the fish including collection site, treatment, size, and previous otolith readings. Fish age (in years) was assigned when two or more counts agreed, which was achieved for all specimens.

Gonads were weighed to the nearest 0.1 g. We were unable to weigh fresh gonads due to the inaccuracy of balances on the research vessel, so gonads were weighed on shore after being fixed in formalin. Formalin-fixed gonad weight is scalable to fresh weight47, and any effect of formalin fixation should be equal across all samples. To confirm macroscopic staging, one lobe from each gonad was used for histological analysis at the Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS, Weymouth, UK). Samples were processed in a Thermo Excelsior AS vacuum infiltration processor, using standard histology protocols. Tissues were embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned (3 μm) using a rotary microtome and stained with haematoxylin and eosin using a Thermo Scientific Varistain Gemini ES automated stainer. Slides were analysed using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope and micrographs were captured using the Nikon NIS Elements BR image analysis software.

A total of 96 females were confirmed as being spawning capable, so were used in all subsequent analyses. All ovaries contained vitellogenic oocytes, but not hydrated oocytes or post-ovulatory follicles. Thus, although all fish were spawning capable, they were not actively spawning nor had they recently spawned during this cycle39. However, given the capability for daily spawning and rapid egg development in parrotfishes, these fish could become active spawners within days. We were unable to count and measure oocytes to determine batch fecundity and mean egg size due to the lack of hydrated oocytes, as estimates from earlier egg stages are unlikely to provide accurate estimates for these metrics. However, especially because all fish were in the exact same reproductive stage, gonadosomatic index (GSI, gonad weight/body weight × 100) provides a reasonable measure of relative reproductive investment, and GSI has been used as an indicator of reproductive investment in previous demographic studies of coral-reef fishes, including of the sister species C. spilurus4,6,48,49.

Statistical analyses

To determine the effects of seabird subsidies on parrotfish demography, we used a series of multi-level Bayesian models (additional details on model specifications provided in Supplementary Methods). Most of our response variables were modelled as a function of rat status (rat-infested with few seabirds versus rat-free with abundant seabirds) with the intercept allowed to vary by the atoll within which each island was located, which helped account for atoll-level environmental differences (Supplementary Table S1). This model framework was used for percent nitrogen, δ15N, GSI, density, biomass, and size distribution of C. sordidus, as well as for island, reef, and environmental characteristics that may help explain any observed differences in C. sordidus demography (Supplementary Table S1). Full descriptions of these models are provided in the supplement, while deviations from this framework are described in detail below.

Models for GSI included fish length as an additional covariate. To ensure that the estimated effect of rat status on GSI was robust to any temporal variation in reproductive investment (see Study sites, collections, and surveys) and observed differences in size-at-age around rat-free and rat-infested islands (see Results), we ran several model variations and report the results from these models in the supplement. Specifically, we included collection day as an additional explanatory variable to account for potential temporal variation, but there was no evidence that this improved model fit. We also modelled GSI as a function of age instead of length. The estimated difference in GSI between rat-free and rat-infested islands was nearly identical in all models (Supplementary Methods).

Density and biomass of C. sordidus from underwater visual surveys were modelled following hurdle gamma distributions with log links because the data were zero-inflated, and size was modelled following an exponentially-modified normal distribution, which enabled us to determine the effect of rat presence on both mean size and the skewness of the size distribution. We ran all models both for all 11 surveyed islands, and for only the 5 surveyed islands which exactly matched collection islands. The results were qualitatively similar, so we present the models with all islands, and thus a larger sample size.

Following17, C. sordidus growth was modelled using the von Bertalanffy growth function as:

where is the observed length at age t, is the estimated asymptotic length, is the theoretical length at age 0, and k is the estimated growth coefficient towards , with an additional term providing an offset to compare k around rat-free versus rat-infested islands. By including the term we allowed k, but not and , to vary between rat-free and rat-infested islands. There was good reason to constrain and in this way, as can then be interpreted as the difference in growth rate between rat-free and rat-infested islands, which is more easily interpretable and biologically-relevant than the difference in growth towards maximum size. Thus, = 0 if there is no difference in growth between rat-free and rat-infested islands, > 0 if growth is faster around rat-free islands, and < 0 if growth is slower around rat-free islands. This parameterization was previously used to compare growth of herbivorous damselfish between many of the same rat-free and rat-infested islands used in our study17, so using the same model also enables us to directly compare our results for parrotfish to those of damselfish. However, to ensure any observed differences in growth were not simply due to this parametrization, we ran an additional model where we allowed both and k to vary by rat status. We found the estimated growth curves and difference in k between rat-free and rat-infested models were similar in the two models, and there was no evidence that differed between rat-free and rat-infested islands even when it was allowed to vary (Supplementary Methods). Furthermore, the model fit was best when only k was allowed to vary by rat status, compared to the model in which both and k were allowed to vary, as well as a model in which neither were allowed to vary (Supplementary Methods).

To further explore differences in growth between rat-free and rat-infested islands, we also modelled length-at-age using a reparameterization of the VBGF in which lengths are estimated for three ages: lphi, lpsi, and lchi (where lphi < lpsi and lchi is the mean of lphi and lpsi)50. We set lphi = 2, lpsi = 6, and lchi = 4, with lphi and lpsi chosen to maximize the range of ages for which we had sufficient data from both rat-free and rat-infested islands. Finally, we compared the maximum age and maximum length of collected parrotfish between rat-free and rat-infested islands by comparing the island-level means of the upper quartile of ages and lengths51. Because we only examined female IP fish, differences in these parameters correspond with differences in age- and size-at-sex change, rather than differences in absolute maximum age and size.

For all models, we used weakly informative priors and selected distributions based on the underlying data in conjunction with model diagnostics (Supplementary Methods)52. All models were run for 4 chains, with at least 3,000 iterations and a warm-up of 1,000 iterations. We conducted graphical posterior predictive checks comparing model fits to the data, and evaluated convergence via traceplots and the Gelman-Ruban convergence diagnostic (R-hat)52. All analyses were conducted in R and implemented in STAN using the package brms53,54. All data and code are publicly available on GitHub (github.com/cbenkwitt/nutrients-fish-demography).

Results

Parrotfish growth and fecundity

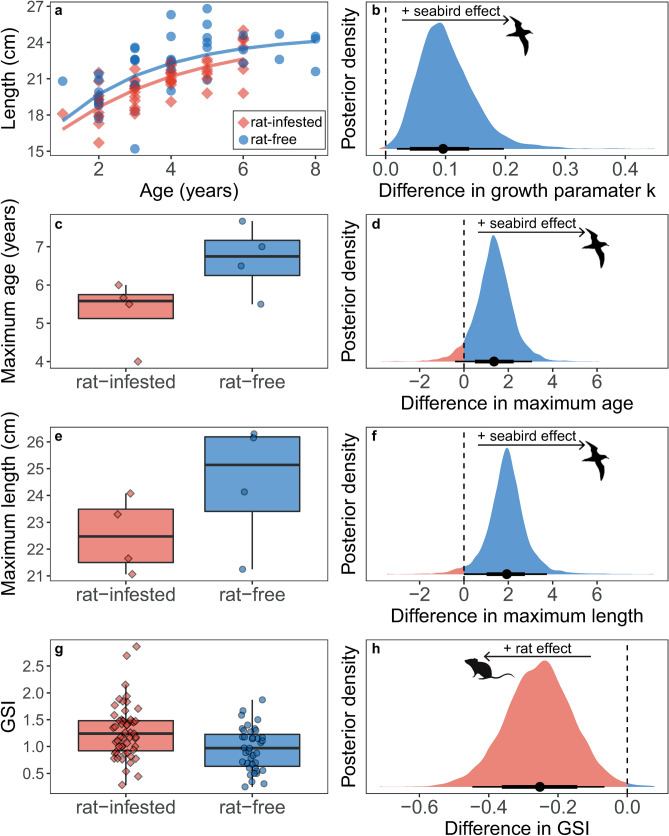

Female C. sordidus around islands with abundant seabird populations grew an estimated 34.91% faster than those around rat-infested islands with few seabirds (Fig. 1a, b; estimated k = 0.38 vs. 0.27; estimated difference in k = 0.10, 95% highest posterior density interval [HPDI] = 0.02 to 0.20). This faster growth coincided with parrotfish around rat-free islands being larger for a given age, with the greatest difference occurring at intermediate ages (4 years old) and the difference diminishing by age 6. Parrotfish around rat-free islands were an estimated 0.65 cm, 2.18 cm, and 0.24 cm larger than those around rat-infested islands at ages 2, 4, and 6, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S3; 95% HPDI for difference in length at age 2 = − 0.33 to 1.61, length at age 4 = 1.18 to 3.42, length at age 6 = − 1.44 to 1.87). Female parrotfish around rat-free islands also reached older maximum ages (estimated maximum age = 6.64 vs. 5.30 years old, estimated difference = 1.36, 95% HPDI = − 0.40 to 3.07) and larger absolute maximum sizes (i.e., not maximum size-at-age) (Fig. 1c–f; estimated maximum length = 24.02 vs. 22.10 cm, estimated difference = 1.93, 95% HPDI = 0.00 to 3.74).

Figure 1.

Demographic rates for female Chlorurus sordidus around rat-free islands with abundant seabirds (blue, circles) compared to rat-infested islands with few seabirds (red, diamonds). (a, g) Each point represents measured values from an individual C. sordidus, (c, e) each point represents one island. (a) Curves represent fitted estimates from Bayesian models, (c, e, g) box limits represent first and third quantiles (25% and 75% percentiles), middle line represents the median (50% percentile), and whiskers represent smallest and largest observations less than or equal to 1.5 × inter-quartile range. (b, d, f, h) Bayesian posterior densities for the effect of seabird presence on the von Bertalanffy growth parameter k (b), maximum age (d), maximum length (f), and relative reproductive investment as measured by GSI (h). Positive values of the posterior distributions (blue fill) indicate a positive effect of seabird presence on the response, negative values (red fill) indicate a negative effect of seabirds (i.e., positive effect of invasive rat presence). Points represent median highest posterior density estimate and lines represent 75% and 95% highest posterior distribution intervals (HPDI). Rat and seabird silhouettes were obtained from phylopic.org under Public Domain Dedication 1.0 licenses.

By contrast, for a given length, the gonadosomatic index (GSI) of parrotfish around rat-free islands was estimated to be 21.04% lower than the GSI of parrotfish around rat-infested islands (Fig. 1g, h; estimated GSI = 0.94 vs. 1.20; estimated difference = − 0.25, 95% HPDI = − 0.45 to − 0.07). There was strong evidence that individual growth rates and GSI were negatively correlated (correlation = − 0.26, 95% CI = − 0.41 to − 0.11).

Parrotfish populations

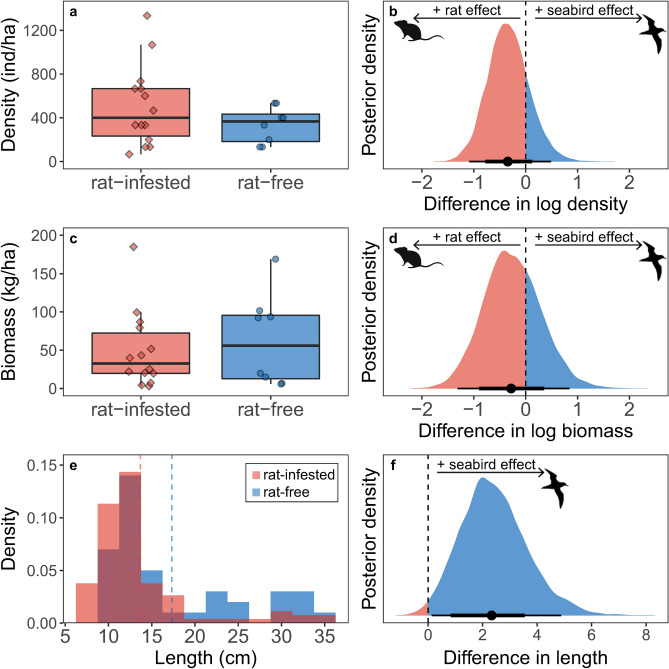

Scaling up from individuals to populations, the density and biomass of C. sordidus were similar around rat-free versus rat-infested islands (Fig. 2a–d; density back-transformed estimate = 0.70, 95% HPDI = 0.28 to 1.45; biomass back-transformed estimate = 0.78, 95% HPDI = 0.18 to 2.01). However, the overall size distribution of C. sordidus was skewed toward larger individuals around islands with abundant seabird populations (estimated difference in skew parameter alpha = 0.46, 95% HPDI = 0.11 to 0.83), and mean length was an estimated 2.33 cm (16.31%) larger around islands with seabirds (Fig. 2e, f; 95% HPDI = 0.13 to 4.88).

Figure 2.

Density, biomass, and size frequency distribution of all Chlorurus sordidus around rat-free islands with abundant seabirds (blue, circles) compared to rat-infested islands with few seabirds (red, diamonds). (a, c) Box limits represent first and third quantiles (25% and 75% percentiles), middle line represents the median (50% percentile), and whiskers represent smallest and largest observations less than or equal to 1.5 × inter-quartile range. Each point represents one transect. Transects on which no C. sordidus were observed were excluded from the boxplots (n = 10 around rat-infested islands, n = 12 around rat-free islands) to correspond to estimates from non-zero components of hurdle gamma models presented in (b, d). (e) Size frequency distribution of C. sordidus in 2.5 cm size bins. (b, d, f) Bayesian posterior densities for the effect of seabird presence on corresponding responses in (a, c, e). Positive values of the posterior distributions (blue fill) indicate a positive effect of seabird presence on the response, negative values (red fill) indicate a negative effect of seabirds (i.e., positive effect of invasive rat presence). Points represent median highest posterior density estimate and lines represent 75% and 95% highest posterior distribution intervals (HPDI). Rat and seabird silhouettes were obtained from phylopic.org under Public Domain Dedication 1.0 licenses.

Potential drivers of demographic differences

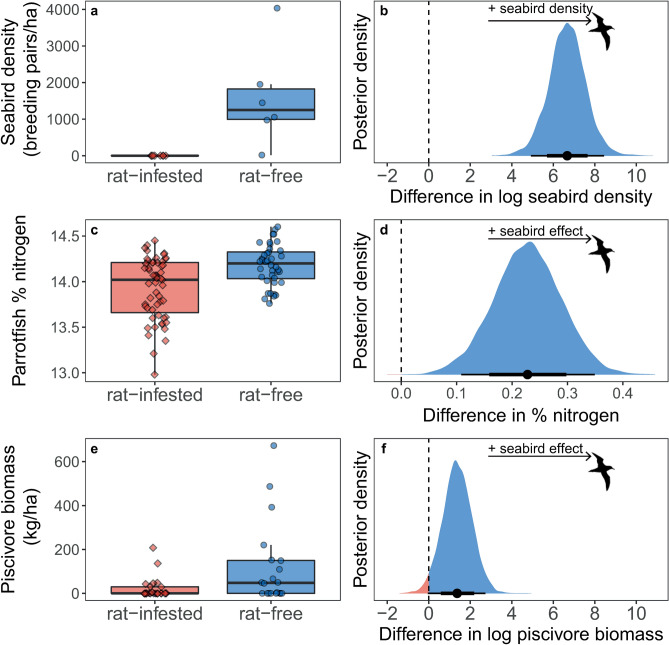

By far the greatest difference between rat-free and rat-infested islands was the density of breeding seabirds. Seabird density was an estimated 788.52 times higher on rat-free versus rat-infested islands, with similar trends regardless of whether only islands where parrotfish were collected and/or only islands where surveys were conducted were included (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2; 95% HPDI = 30.70 to 3307.33).

Figure 3.

Potential drivers of demographic differences in Chlorurus sordidus around rat-free islands with abundant seabirds (blue, circles) compared to rat-infested islands with few seabirds (red, diamonds). (a, c, e) Box limits represent first and third quantiles (25% and 75% percentiles), middle line represents the median (50% percentile), and whiskers represent smallest and largest observations less than or equal to 1.5 × inter-quartile range. Each point represents (a) an island, (b) measured values from an individual C. sordidus, or (c) a transect. (b, d, f) Bayesian posterior densities for the effect of seabird presence on the corresponding responses in (a, c, e). Positive values of the posterior distributions (blue fill) indicate a positive effect of seabird presence on the response, negative values (red fill) indicate a negative effect of seabirds (i.e., positive effect of invasive rat presence). Points represent median highest posterior density estimate and lines represent 75% and 95% highest posterior distribution intervals (HPDI). Rat and seabird silhouettes were obtained from phylopic.org under Public Domain Dedication 1.0 licenses.

At an individual-level, C. sordidus around islands with abundant seabird populations (rat-free islands) had higher percent nitrogen in their muscle than C. sordidus around islands with few seabirds (rat-infested) (estimated difference = 0.23, 95% HPDI = 0.11 to 0.35) (Fig. 3c, d). However, there was no evidence for elevated δ15N in parrotfish around rat-free islands (estimated difference = 0.02, 95% HPDI = − 0.16 to 0.19) (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Piscivore biomass was also greater around rat-free islands by a factor of 3.93 (95% HPDI = 0.42 to 12.73; Fig. 3e, f), which was driven by a combination of both greater densities and larger sizes around rat-free versus rat-infested islands (Supplementary Fig. S5; estimated difference in density = 2.70 times, 95% HPDI 0.16 to 9.85, estimated difference in mean size = 7.70 cm, 95% HPDI = 1.91 to 13.57). By contrast, other external factors that can influence fish demography, including coral cover, structural complexity, sea temperature, net primary productivity, and wave exposure, were all similar between rat-free and rat-infested islands (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2).

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, nutrient subsidies from seabirds did not uniformly boost demographic rates of parrotfish on adjacent coral reefs. Instead, female parrotfish around rat-free islands with abundant seabird populations exhibited increased growth and size-at-age, but reduced reproductive investment for a given size, than parrotfish around rat-infested islands with few seabirds. Combined, these results suggest that parrotfish around rat-free versus rat-infested islands exhibit different life-history strategies. Differences in densities of breeding seabirds on these islands are likely the ultimate driver of these demographic differences, with proximate drivers including enhanced quality of food resources and/or enhanced piscivore populations, and thus increased size-selective mortality, around rat-free islands. Although these altered life-history characteristics did not correspond with observable differences in population-level biomass of C. sordidus, both mean size and overall size distribution were shifted toward larger individuals around rat-free islands. Furthermore, the faster growth rates and larger sizes can drive other demographic changes (e.g., lower mortality rates55), and increase the functional importance of parrotfish (e.g., higher bioerosion rates21–25). More broadly, these results have implications for understanding the extent and scales at which cross-ecosystem nutrient subsidies provide benefits.

Drivers of demographic trade-offs

Our results provide evidence for a trade-off between investing in early growth versus reproduction, with parrotfish around rat-free islands reaching larger sizes more quickly, but at the cost of limiting their size-based reproductive investment. By contrast, parrotfish around rat-infested islands exhibited the opposite pattern of slower growth rates and reduced maximum size- and age-at-sex change, but enhanced GSI for a given size. Importantly, the magnitude of these demographic differences was similar to those observed for coral-reef fishes across broad gradients in myriad biotic and environmental variables, including latitude, temperature, fishing pressure, wave exposure, resource availability, and predator density2,4,5,35,56–60. Such differences often occur among study sites ranging from tens to thousands of kilometres apart, whereas our study focused on nearby islands within atolls, suggesting strong local drivers of demographic variation in these parrotfish.

Where abundant, seabirds have large effects that can transfer throughout entire food webs in both terrestrial and nearshore marine systems. Their allochotonous nutrient inputs drive bottom-up changes in the demographic rates, abundance, biomass, and community structure of primary producers, primary consumers, and higher-order predators1,10,17,61–63. These large documented effects of seabird-derived nutrients, combined with the large difference in seabird populations between rat-free versus rat-infested islands in our study, suggest that they are the primary drivers of local demographic variation in parrotfish observed here. Indeed, a range of environmental drivers were found not to differ between the two island treatment types. Seabirds are likely driving differences in parrotfish demographics via two non-mutually exclusive pathways—(1) seabird derived-nutrients have direct bottom-up effects on parrotfish via increased food quality, and (2) seabird-derived nutrients drive larger piscivore populations, which in turn exert top-down effects on parrotfish. We explore each of these pathways in detail below.

The enhanced growth rates of C. sordidus around islands with seabirds is consistent with theoretical predictions and empirical results from the bottom-up effects of nutrient subsidies on resource quality and/or quantity3,10,11,17. Because parrotfish feed on microscopic autotrophs contained within the reef matrix and found on various substrates including tufted cyanobacteria, turf algae, crustose coralline algae, dead coral, eroded reef substrate, and sponges19,20, it was not feasible to directly quantify the availability or quality of their food in this study. However, live coral cover, which is negatively correlated with food availability for parrotfish20,42, was similar between rat-free and rat-infested islands40, suggesting that resource quantity was also comparable between island types. By contrast, several lines of evidence suggest that enhanced food quality is at least partially driving the observed increased growth. Nearshore reefs around rat-free islands receive large inputs of nitrogen and phosphorous derived from seabird guano10,15,17, both of which are typically limiting nutrients for herbivore growth64. The elevated nitrogen content in C. sordidus around rat-free islands suggests that they are assimilating these extra nutrients. Similarly, marine algae, sponges, corals, zooplankton, invertebrates, and damselfish assimilate seabird-derived nitrogen around islands with abundant seabirds17,45,46,65,66, and these excess nutrients have been linked to enhanced growth rates in corals and herbivorous damselfish17,46. Indeed, the relative magnitude of elevated growth of C. sordidus is similar to that of the damselfish Plectroglyphidodon lacrymatus from these reefs17, suggesting that effects pervade across taxa of differing body sizes and highlighting just how influential seabird-derived nutrient subsidies can be on coral reefs.

In light of the observed differences in nitrogen content and growth rates of parrotfish, it was somewhat surprising that there was no difference in δ15N. Elevated δ15N values are indicative of seabird-derived nitrogen in nearshore tropical marine food chains17,45,46, and are typically correlated with nitrogen content45. One explanation for the lack of δ15N differences in C. sordidus is that their preferred diet of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria have depleted δ15N values relative to other food sources, resulting in lower δ15N signatures in parrotfish compared to other herbivores19,67. Despite having overall lower δ15N, some types of cyanobacteria have still been shown to incorporate nitrogen from seabirds, although they have high standard deviations around these δ15N values68, which may make detection of seabird effects more difficult in cyanobacteria-feeding organisms. A more likely explanation is that seabird-derived nutrients facilitate nitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria by supplying phosphorous, as has been shown for terrestrial run-off and groundwater69. Such a pathway is consistent with the observed elevated nitrogen, but not δ15N, in C. sordidus feeding on cyanobacteria. The supply of phosphorous from seabird guano may also affect demographic rates of parrotfish more directly, as growth in a number of fish species is phosphorous-limited70. Thus, even without elevated δ15N values, there is a probable link between seabird-derived nutrients and food resources, nitrogen content, and demographic rates of parrotfish.

While the enhanced growth rates are consistent with bottom-up effects of nutrient subsidies, the lower size-related reproductive investment in the presence of high resource quality was counter to our expectations71. We found no previous examples of consumer-derived nutrient subsidies resulting in reduced fecundity or reproductive investment, although few studies have tested for this relationship1,3. More broadly, lab and field experiments using a range of taxa have shown that when consumers are nutrient-limited they prioritize resource allocation to maintenance or storage rather than reproduction13. A key question then is why did C. sordidus around islands with abundant seabird populations maximize early growth above reproductive investment? One likely explanation is that piscivore biomass was higher around islands with abundant seabirds17,40, due to both higher densities and larger sizes of predators near rat-free islands . Because fish predators are often gape-limited, faster growth rates can increase survival of prey fish by reducing the time they are susceptible to size-selective predation25,72. Indeed, variation in the demographic rates and size structures of lower-trophic level fishes has repeatedly been linked to piscivore population size across a gradient of fishing pressure in the Line and Hawaiian Islands58,60,73,74. Thus, in the presence of high predation intensity around rat-free islands, it may be more advantageous for C. sordidus to devote their energy to increased growth at the cost of reduced reproduction, at least while in their initial phase. In addition to these cost differences in energetic trade-offs around rat-free versus rat-infested islands, higher size-selective mortality rates for slow growers in the presence of abundant piscivores would similarly result in more fast growing individuals around rat-free islands. In other words, in addition to nutrient subsidies having a direct bottom-up effect on the demographic rates of parrotfish, seabird-derived nutrients also extend up the food web to boost the density and biomass of piscivores17, which in turn exert increased top-down control on parrotfish.

By contrast, it is unlikely intraspecific competition was a major driver of the observed demographic differences, because we found no difference in the population density of C. sordidus around rat-free versus rat-infested islands. Furthermore, although total biomass of parrotfish (Supplementary Fig. S6) and herbivores17,40 is higher around rat-free islands, this is unlikely to lead to more intense interspecific competition due to fine-scale niche separation among parrotfishes19.

Finally, related metrics that we were unable to measure may provide additional explanations for the observed growth-reproduction trade-offs. In addition to allocating energy to growth and reproduction, animals also devote energy to maintenance and storage14. These parrotfish were collected several years following a major coral bleaching event, a time when they had access to abundant resources75. Indeed, parrotfish exhibited increased growth during this time in a pan-tropical study, as declines in coral cover lead to increases in food resources for parrotfish19,75. Although there was no difference in coral cover between rat-free and rat-infested islands40, the overall low coral cover during these years likely meant that food availability was not limiting around islands with either rat status. Presumably, however, when resources are scarce seabird-derived nutrients may be even more important, possibly leading to pronounced variation in energy storage or condition. Determining how nutrient subsidies influence multiple demographic rates at other times and in other species is an important area for future research, and may further explain the patterns in energy allocation observed here.

Implications of demographic differences

On coral reefs, demographic traits are linked to higher-order processes in part due to non-linear scaling of many traits with body size. Notably, the enhanced growth rates and larger sizes of C. sordidus could influence ecosystem function. As an excavating herbivore, C. sordidus plays a key role in bioerosion and sediment production22,33 with larger individuals contributing disproportionately more to these functional roles than smaller individuals22–24. Based on our re-paramaterized VBGF results, combined with published allometric scaling relationships for C. sordidus23, a 4-year old individual near a rat-free island will have an annual grazing rate of 46.5 m2 compared to just 37.3 m2 around a rat-infested island, and an annual bioerosion rate of 14.1 kg versus 11.3 kg (95% HPDI grazing rat-free = 42.1 to 51.3, rat-infested = 34.7 to 40.0; bioerosion rat-free = 12.8 to 15.6, rat-infested = 10.6 to 12.2).

Parrotfish, including C. sordidus, are also important components of subsistence and commercial harvests in many regions. Fisheries productivity is strongly influenced by growth trajectories and mortality rates76. Therefore, the increased growth rates of parrotfish from seabird-derived subsidies could enhance fishery productivity. Because a higher proportion of older age and size classes were observed at rat-free sites, which is strongly indicative of lower mortality rates55, there may be additional boosts in productivity. Importantly, standing biomass is often decoupled from fish and fishery productivity on tropical reefs76, so this boost in productivity can occur despite similar biomass of C. sordidus around rat-free and rat-infested islands. Thus, even in the absence of a consistent numeric response, seabirds can influence population and community dynamics, as well as ecosystem functioning.

While growth rates and sizes of parrotfish can be tightly linked to local ecosystem function, reproductive characteristics are linked to regional dynamics via larval dispersal. Although individual reproductive investment was higher for female parrotfish around rat-free islands, several other factors influence reproductive output and success. For example, differences in size-at-sex change can behaviourally influence reproductive success beyond individual fecundity56, such that a larger size-at-sex change can result in greater lifetime reproductive output despite lower size-related reproductive investment. We found greater maximum sizes and ages of female parrotfish around rat-free islands, which is consistent with the typical association between larger size-at-sex change with faster growth and larger mean size, especially when coupled with similar population densities56. These differences in age- and size-at-sex change between rat-free and rat-infested islands may offset the observed differences in relative reproductive investment. Furthermore, not only do larger, older females produce more eggs, but they also produce larger and higher quality eggs, and have earlier and longer spawning seasons than smaller females77. Increases in reproductive energy also scale allometrically with female body size for the majority of fish species, including for C. sordidus78. Thus, the observed differences in body size and age between rat-free and rat-infested islands may further influence reproductive output and success beyond GSI.

Although we could not directly measure whether population-level reproductive output differs between rat-free and rat-infested islands, conservative calculations suggest that there was no difference in total, instantaneous, reproductive potential (Supplementary Fig. S7). In other words, although individuals around rat-infested islands had higher reproductive investment for a given size, this did not result in higher population-level reproductive output. This study is only the first step in quantifying the effects of seabird nutrient subsidies on coral-reef fish reproduction, and future work detailing additional factors that influence reproductive dynamics, including sex ratios, egg quality, fecundity of males and females, and larval dispersal patterns, will clarify the regional implications of nutrient subsidies for coral-reef fish populations.

Management implications

Many island nations are now prioritizing rat eradication as a relatively simple, low-cost management action with potential widespread benefits, including restoring seabird populations and their associated nutrient subsidies79,80. These results help clarify some possible outcomes of these management actions. Here, we add to growing evidence that rat eradication may benefit not only terrestrial systems, but also nearshore coral reefs17,18,40,46,81, as measured by higher growth rates of functionally important parrotfish near rat-free islands. However, we did not find any direct benefits of seabird-derived nutrients for reproductive investment of individuals, and there was no difference in population-level instantaneous reproductive potential between rat-free and rat-infested islands. Although there may still be lifetime reproductive benefits to fish around rat-free islands due to lower mortality rates and/or larger size-at-sex change, we currently have no evidence that increased larval export to other reefs is an additional benefit of local eradication programs. Therefore, the benefits of seabird-derived nutrient subsidies are likely spatially-restricted, meaning that managers should seek to de-rat entire archipelagos to provide the most benefits for coral reefs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This Project was funded by the Bertarelli Foundation and contributed to the Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science, and the Royal Society (UF140691). Fieldwork was conducted under permits 0004SE18 and 0001SE19. Ethical approval was granted by the Lancaster University Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (AWERB permit number A100143). D. Hughes conducted the isotope analysis, J. Bignell facilitated the histological analysis, and M. Adreani, K. Scafidi, and M. Steele provided assistance with attempted batch fecundity and egg size analyses. Rat and seabird silhouettes were obtained from PhyloPic under public domain licenses.

Author contributions

C.E.B. conceived of the study with N.A.J.G. C.E.B. conducted statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. B.M.T. performed all otolith processing and analysis. All authors contributed to designing the study, collecting and processing specimens in the field, and revising the manuscript. All authors gave approval for submission and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Data availability

All data and code are publicly available on GitHub (github.com/cbenkwitt/nutrients-fish-demography).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-91884-y.

References

- 1.Pafilis P, et al. Reproductive biology of insular reptiles: marine subsidies modulate expression of the ‘island syndrome’. Copeia. 2011;2011:545–552. doi: 10.1643/CE-10-041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruttenberg BI, Haupt AJ, Chiriboga AI, Warner RR. Patterns, causes and consequences of regional variation in the ecology and life history of a reef fish. Oecologia. 2005;145:394–403. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilderbrand GV, et al. The importance of meat, particularly salmon, to body size, population productivity, and conservation of North American brown bears. Can. J. Zool. 1999;77:132–138. doi: 10.1139/z98-195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gust N. Variation in the population biology of protogynous coral reef fishes over tens of kilometres. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2004;61:205–218. doi: 10.1139/f03-160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifton K. Asynchronous food availability on neighboring Caribbean coral reefs determines seasonal patterns of growth and reproduction for the herbivorous parrotfish Scarus iserti. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995;116:39–46. doi: 10.3354/meps116039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein ED, D’Alessandro EK, Sponaugle S. Demographic and reproductive plasticity across the depth distribution of a coral reef fish. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34077. doi: 10.1038/srep34077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pérez-Ruzafa A, Pérez-Marcos M, Marcos C. From fish physiology to ecosystems management: keys for moving through biological levels of organization in detecting environmental changes and anticipate their consequences. Ecol. Ind. 2018;90:334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal AA. Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science. 2001;294:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie HM, Breck EN, Chan F, Lubchenco J, Menge BA. Barnacle reproductive hotspots linked to nearshore ocean conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:10534–10539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503874102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polis GA, Anderson WB, Holt RD. Toward an integration of landscape and food web ecology: the dynamics of spatially subsidized food webs. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1997;28:289–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundberg J, Moberg F. Mobile link organisms and ecosystem functioning: implications for ecosystem resilience and management. Ecosystems. 2003;6:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s10021-002-0150-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glazier DS. Trade-offs between reproductive and somatic (storage) investments in animals: a comparative test of the Van Noordwijk and De Jong model. Evol. Ecol. 1999;13:539–555. doi: 10.1023/A:1006793600600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zera AJ, Harshman LG. The physiology of life history trade-offs in animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001;32:95–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stearns SC. The Evolution of Life Histories. OUP Oxford; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otero XL, Peña-Lastra SDL, Pérez-Alberti A, Ferreira TO, Huerta-Diaz MA. Seabird colonies as important global drivers in the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:246. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02446-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones HP, et al. Severity of the effects of invasive rats on seabirds: a global review. Conserv. Biol. 2008;22:16–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham NAJ, et al. Seabirds enhance coral reef productivity and functioning in the absence of invasive rats. Nature. 2018;559:250–253. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benkwitt CE, Wilson SK, Graham NAJ. Biodiversity increases ecosystem functions despite multiple stressors on coral reefs. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:919–926. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clements KD, German DP, Piché J, Tribollet A, Choat JH. Integrating ecological roles and trophic diversification on coral reefs: multiple lines of evidence identify parrotfishes as microphages. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2017;120:729–751. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson GM, Clements KD. Resolving resource partitioning in parrotfishes (Scarini) using microhistology of feeding substrata. Coral Reefs. 2020;39:1313–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01964-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonaldo R, Hoey A, Bellwood D. The ecosystem roles of parrotfishes on tropical reefs. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 2014;52:81–132. doi: 10.1201/b17143-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoey AS. Feeding in parrotfishes: the influence of species, body size, and temperature. In: Hoey AS, Bonaldo RM, editors. Biology of Parrotfishes. CRC Press; 2018. pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange ID, et al. Site-level variation in parrotfish grazing and bioerosion as a function of species-specific feeding metrics. Diversity. 2020;12:379. doi: 10.3390/d12100379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lokrantz J, Nyström M, Thyresson M, Johansson C. The non-linear relationship between body size and function in parrotfishes. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:967–974. doi: 10.1007/s00338-008-0394-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mumby PJ, et al. Fishing, trophic cascades, and the process of grazing on coral reefs. Science. 2006;311:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1121129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green AL, et al. Larval dispersal and movement patterns of coral reef fishes, and implications for marine reserve network design. Biol. Rev. 2015;90:1215–1247. doi: 10.1111/brv.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham NAJ, McClanahan TR. The last call for marine wilderness? Bioscience. 2013;63:397–402. doi: 10.1525/bio.2013.63.5.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hays GC, et al. A review of a decade of lessons from one of the world’s largest MPAs: conservation gains and key challenges. Mar. Biol. 2020;167:159. doi: 10.1007/s00227-020-03776-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheppard CRC, et al. Reefs and islands of the Chagos Archipelago, Indian Ocean: why it is the world’s largest no-take marine protected area. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat. Ecosyst. 2012;22:232–261. doi: 10.1002/aqc.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr P, et al. Status and phenology of breeding seabirds and a review of Important bird and biodiversity areas in the British Indian Ocean Territory. Bird Conserv. Int. 2021;31:14–34. doi: 10.1017/S0959270920000295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilton GM, Cuthbert RJ. The catastrophic impact of invasive mammalian predators on birds of the UK Overseas Territories: a review and synthesis. Ibis. 2010;152:443–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2010.01031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoddart DR. Rainfall on Indian Ocean coral islands. Atoll Res. Bull. 1971;147:1–21. doi: 10.5479/si.00775630.147.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry CT, Kench PS, O’Leary MJ, Morgan KM, Januchowski-Hartley F. Linking reef ecology to island building: parrotfish identified as major producers of island-building sediment in the Maldives. Geology. 2015;43:503–506. doi: 10.1130/G36623.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeager LA, Marchand P, Gill DA, Baum JK, McPherson JM. Marine Socio-Environmental Covariates: queryable global layers of environmental and anthropogenic variables for marine ecosystem studies. Ecology. 2017;98:1976–1976. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor BM, Trip EDL, Choat JH. Dynamic demography: investigations of life-history variation in the parrotfishes. In: Hoey AS, Bonaldo RM, editors. Biology of Parrotfishes. CRC Press; 2018. pp. 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colin PL, Bell LJ. Aspects of the spawning of labrid and scarid fishes (Pisces: Labroidei) at Enewetak Atoll, Marshall Islands with notes on other families. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1991;31:229–260. doi: 10.1007/BF00000690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bay LK, Choat JH, van Herwerden L, Robertson DR. High genetic diversities and complex genetic structure in an Indo-Pacific tropical reef fish (Chlorurus sordidus): evidence of an unstable evolutionary past? Mar. Biol. 2004;144:757–767. doi: 10.1007/s00227-003-1224-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer CG, Papastamatiou YP, Clark TB. Differential movement patterns and site fidelity among trophic groups of reef fishes in a Hawaiian marine protected area. Mar. Biol. 2010;157:1499–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00227-010-1424-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown-Peterson NJ, Wyanski DM, Saborido-Rey F, Macewicz BJ, Lowerre-Barbieri SK. A standardized terminology for describing reproductive development in fishes. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2011;3:52–70. doi: 10.1080/19425120.2011.555724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benkwitt CE, Wilson SK, Graham NAJ. Seabird nutrient subsidies alter patterns of algal abundance and fish biomass on coral reefs following a bleaching event. Glob. Change Biol. 2019;25:2619–2632. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Froese R, Pauly D. FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor BM, et al. Synchronous biological feedbacks in parrotfishes associated with pantropical coral bleaching. Glob. Change Biol. 2020;26:1285–1294. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polunin NVC, Roberts CM. Greater biomass and value of target coral-reef fishes in two small Caribbean marine reserves. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993;100:167–176. doi: 10.3354/meps100167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson SK, Graham NAJ, Polunin NVC. Appraisal of visual assessments of habitat complexity and benthic composition on coral reefs. Mar. Biol. 2007;151:1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0538-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCauley DJ, et al. From wing to wing: the persistence of long ecological interaction chains in less-disturbed ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:409. doi: 10.1038/srep00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savage C. Seabird nutrients are assimilated by corals and enhance coral growth rates. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4284. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurita Y, Meier S, Kjesbu OS. Oocyte growth and fecundity regulation by atresia of Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) in relation to body condition throughout the maturation cycle. J. Sea Res. 2003;49:203–219. doi: 10.1016/S1385-1101(03)00004-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoey J, McCormick MI, Hoey AS. Influence of depth on sex-specific energy allocation patterns in a tropical reef fish. Coral Reefs. 2007;26:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0246-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tootell JS, Steele MA. Distribution, behavior, and condition of herbivorous fishes on coral reefs track algal resources. Oecologia. 2015;181:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s00442-015-3418-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Francis RICC. Are growth parameters estimated from tagging and age-length data comparable? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1988;45:936–942. doi: 10.1139/f88-115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choat JH, Robertson DR. Age-based studies. In: Sale PF, editor. Coral Reef Fishes: Dynamics and Diversity in a Complex Ecosystem. Academic Press; 2002. pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McElreath R. Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan. CRC Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bürkner PC. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017;80:1–28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v080.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bürkner PC. Advanced Bayesian multilevel modeling with the R package brms. R J. 2018;10:395–411. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2018-017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoenig JM. Empirical use of longevity data to estimate mortality rates. Fish. Bull. 1983;82:898–903. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor BM, et al. Bottom-up processes mediated by social systems drive demographic traits of coral-reef fishes. Ecology. 2018;99:642–651. doi: 10.1002/ecy.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor BM. Drivers of protogynous sex change differ across spatial scales. Proc. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20132423. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruttenberg BI, et al. Predator-induced demographic shifts in coral reef fish assemblages. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gust N, Choat J, Ackerman J. Demographic plasticity in tropical reef fishes. Mar. Biol. 2002;140:1039–1051. doi: 10.1007/s00227-001-0773-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedlander A, DeMartini E. Contrasts in density, size, and biomass of reef fishes between the northwestern and the main Hawaiian islands: the effects of fishing down apex predators. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002;230:253–264. doi: 10.3354/meps230253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richardson KM, Iverson JB, Kurle CM. Marine subsidies likely cause gigantism of iguanas in the Bahamas. Oecologia. 2019;189:1005–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00442-019-04366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Croll DA, Maron JL, Estes JA, Danner EM, Byrd GV. Introduced predators transform subarctic islands from grassland to tundra. Science. 2005;307:1959–1961. doi: 10.1126/science.1108485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briggs AA, et al. Effects of spatial subsidies and habitat structure on the foraging ecology and size of geckos. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sterner RW, Elser JJ. Ecological Stoichiometry: the Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere. Princeton University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kolb G, Ekholm J, Hambäck P. Effects of seabird nesting colonies on algae and aquatic invertebrates in coastal waters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010;417:287–300. doi: 10.3354/meps08791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lorrain A, et al. Seabirds supply nitrogen to reef-building corals on remote Pacific islets. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3721. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03781-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Plass-Johnson JG, McQuaid CD, Hill JM. Stable isotope analysis indicates a lack of inter- and intra-specific dietary redundancy among ecologically important coral reef fishes. Coral Reefs. 2013;32:429–440. doi: 10.1007/s00338-012-0988-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mizutani H, Wada E. Nitrogen and carbon isotope ratios in seabird rookeries and their ecological implications. Ecology. 1988;69:340–349. doi: 10.2307/1940432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erler DV, et al. Has nitrogen supply to coral reefs in the south Pacific Ocean changed over the past 50 thousand years? Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2019;34:567–579. doi: 10.1029/2019PA003587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Benstead JP, et al. Coupling of dietary phosphorus and growth across diverse fish taxa: a meta-analysis of experimental aquaculture studies. Ecology. 2014;95:2768–2777. doi: 10.1890/13-1859.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McBride RS, et al. Energy acquisition and allocation to egg production in relation to fish reproductive strategies. Fish Fish. 2015;16:23–57. doi: 10.1111/faf.12043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sogard SM. Size-selective mortality in the juvenile stage of teleost fishes: a review. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1997;60:1129–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walsh SM, Hamilton SL, Ruttenberg BI, Donovan MK, Sandin SA. Fishing top predators indirectly affects condition and reproduction in a reef-fish community. J. Fish Biol. 2012;80:519–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DeMartini E, Friedlander A, Holzwarth S. Size at sex change in protogynous labroids, prey body size distributions, and apex predator densities at NW Hawaiian atolls. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005;297:259–271. doi: 10.3354/meps297259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taylor BM, et al. Synchronous biological feedbacks in parrotfishes associated with pantropical coral bleaching. Glob. Change Biol. 2020;26:1285–1294. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Morais RA, Bellwood DR. Principles for estimating fish productivity on coral reefs. Coral Reefs. 2020;39:1221–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01969-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hixon MA, Johnson DW, Sogard SM. BOFFFFs: on the importance of conserving old-growth age structure in fishery populations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014;71:2171–2185. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barneche DR, Robertson DR, White CR, Marshall DJ. Fish reproductive-energy output increases disproportionately with body size. Science. 2018;360:642–645. doi: 10.1126/science.aao6868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buckner EV, Hernández DL, Samhouri JF. Conserving connectivity: Human influence on subsidy transfer and relevant restoration efforts. Ambio. 2018;47:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s13280-017-0989-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones HP, et al. Invasive mammal eradication on islands results in substantial conservation gains. PNAS. 2016;113:4033–4038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521179113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benkwitt CE, Gunn RL, Le Corre M, Carr P, Graham NAJ. Rat eradication restores nutrient subsidies from seabirds across terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Current Biology. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and code are publicly available on GitHub (github.com/cbenkwitt/nutrients-fish-demography).