Summary

Revertant mosaicism, or “natural gene therapy,” refers to the spontaneous in vivo reversion of an inherited mutation in a somatic cell. Only approximately 50 human genetic disorders exhibit revertant mosaicism, implicating a distinctive role played by mutant proteins in somatic correction of a pathogenic germline mutation. However, the process by which mutant proteins induce somatic genetic reversion in these diseases remains unknown. Here we show that heterozygous pathogenic CARD14 mutations causing autoinflammatory skin diseases, including psoriasis and pityriasis rubra pilaris, are repaired mainly via homologous recombination. Rather than altering the DNA damage response to exogenous stimuli, such as X-irradiation or etoposide treatment, mutant CARD14 increased DNA double-strand breaks under conditions of replication stress. Furthermore, mutant CARD14 suppressed new origin firings without promoting crossover events in the replication stress state. Together, these results suggest that mutant CARD14 alters the replication stress response and preferentially drives break-induced replication (BIR), which is generally suppressed in eukaryotes. Our results highlight the involvement of BIR in reversion events, thus revealing a previously undescribed role of BIR that could potentially be exploited to develop therapeutics for currently intractable genetic diseases.

Keywords: revertant mosaicism, CARD14, pityriasis rubra pilaris type V, homologous recombination, replication stress, break-induced replication, NF-κB

Introduction

Eukaryotic genomes are inevitably challenged by extrinsic and intrinsic stresses that threaten genome integrity. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are the most toxic and mutagenic of DNA lesions,1, 2, 3 arising both exogenously as a consequence of exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) and certain chemicals and endogenously as a result of replication stress or reactive oxygen species. Homologous recombination (HR) is a crucial pathway involved in DSB repair and replication stress response (RSR).4, 5, 6 HR is generally regarded as a genetically silent event in mitotic cells because it preferentially occurs between sister chromatids following chromosomal replication. However, if HR occurs via a homologous chromosome, it can lead to loss of heterozygosity (LoH), which contributes to cancer initiation and progression,7 tissue remodelling,8,9 and notably, somatic genetic rescue events (referred to as revertant mosaicism [RM]10) in Mendelian diseases.11 To date, only approximately 50 human genetic disorders have been reported to exhibit RM,12 which may be due, in part, to the technical difficulties associated with detecting this phenomenon in certain tissues. In particular, in some genetic skin diseases, each individual develops dozens to thousands of revertant skin patches where a heterozygous pathogenic germline mutation is reverted via LoH,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 suggesting that HR may be enhanced in mutant keratinocytes, the major cells of the epidermis. Manipulating HR to induce the reversion of disease-causing mutations may potentially benefit individuals with various genetic diseases for which only symptomatic treatment is currently available. However, the process by which mutant proteins induce increased rates of HR in these diseases remains unknown.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP [MIM: 173200]) is a group of rare chronic inflammatory skin disorders that are clinically characterized by keratotic follicular papules, well-demarcated scaly erythematous plaques interspersed with distinct islands of unaffected skin, and palmoplantar keratoderma. PRP is classified into six subtypes based on the age of onset, clinical features, and prognosis.18,19 The PRP type V (PRPV) or familial PRP has autosomal-dominant inheritance and is associated with gain-of-function mutations in CARD14 (MIM: 607211).20 Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 14 (CARD14), encoded by CARD14, is a scaffold molecule predominantly expressed in keratinocytes. Heterozygous mutations in CARD14 also lead to psoriasis (MIM: 602723)21 and mutant CARD14 (mut-CARD14) triggers the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling with subsequent disruption of skin homeostasis, inflammation, and hyperproliferation of keratinocytes.20, 21, 22

Here, we present evidence of HR-induced RM in PRPV. We aimed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying this self-healing phenomenon by analyzing the impact of mut-CARD14 on DNA damage and replication stress, as well as the response to these events. Our findings indicate that mut-CARD14 may play an important role in genetic reversion by enhancing BIR under replication stress.

Material and methods

Human subjects and study approval

Individuals participating in the study provided written informed consent, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine (project No. 14-063). Both individuals provided a peripheral blood or saliva sample and skin samples from affected skin and revertant spots.

Genomic DNA extraction

For mutation analysis, genomic DNA from the individuals’ peripheral blood or saliva was extracted using a QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit (QIAGEN) or an Oragene DNA Self-Collection Kit (DNA Genotek), respectively. Genomic DNA was also extracted from individuals’ skin samples using a QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN) after separating the epidermis from the dermis of punch-biopsied skin samples using an ammonium thiocyanate solution, as described previously.23

Sanger sequencing

Exons and exon-intron boundaries in CARD14 (GenBank: NM_024110.4) were amplified via PCR using AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available upon request. PCR amplicons were treated with ExoSAP-IT reagent (Affymetrix), and the sequencing reaction was performed using BigDye Terminator v.3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequence data were obtained using an ABI 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Whole-genome oligo-single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array

CytoScan HD Array (Affymetrix) was used to identify copy number variations (CNVs) and LoHs using genomic DNA extracted from the epidermis (outsourced to RIKEN Genesis). All experimental procedures were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 250 ng of each genomic DNA sample was digested with NspI and ligated to adaptors, followed by PCR amplification. Following purification, fragmentation, and biotinylation of the PCR products, samples were hybridized to the Affymetrix CytoScan HD Array. After washing and staining, fluorescent signals were obtained with a GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix) and GeneChip Command Console (Affymetrix). The data were then analyzed using Chromosome Analysis Suite Software 4.0 (Affymetrix) by filtering CNVs with a minimum size of 400 kbp and 50 consecutive markers, and LoHs with a minimum size of 3,000 kbp and 50 consecutive markers. For each marker, the allelic difference is calculated as the difference between the summarized signal of the A allele minus B allele, standardized such that an A-allele genotype is scaled to a positive value, and the B allele is scaled to a negative value. In these analyses, therefore, a homozygous AA allele maps to approximately +1 and a homozygous BB allele maps to approximately −1, with the heterozygote mapping to approximately 0.

Cell culture, X-irradiation, and drug treatment

U2OS (ATCC), the human osteosarcoma cell line, and HaCaT (CLS Cell Lines Service), the commercially available immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) with, or without, 1% Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution (Sigma-Aldrich). To examine the response to X-irradiation, 150 kV X-ray was delivered at 20 mA with a 1 mm aluminum filter at a distance of 350 mm from the cell surface. To analyze the response to etoposide, cells were treated with 10 or 250 μM etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich) for indicated time periods since etoposide was reported to induce two types of DNA damage mechanisms depending on its concentration.24 To investigate their responses to HU and APH, cells were treated with 2 mM hydroxyurea (HU) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 μg/mL aphidicolin (APH) (Sigma-Aldrich) for indicated time periods, respectively. To directly activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, cells were incubated with tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (R&D Systems). The cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Nacalai Tesque) before addition of drug-free medium and incubated as necessary.

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RNA extraction and reverse transcription were performed using a SuperPrep II Cell Lysis & RT Kit for qPCR (Toyobo). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using the Quant Studio 12K Flex Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and TaqMan MGB probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To assess the expression levels of CARD14 and inflammatory chemokines, the following TaqMan probes were used: CARD14 (Hs01106900_m1), IL8 (Hs00174103_m1), and CCL20 (Hs00355476_m1). For the analysis of replication-related genes, Custom TaqMan Array Cards (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used. Target genes and their corresponding TaqMan probes were as follows: ORC1 (Hs01069758_m1), ORC6 (Hs00941233_g1), MCM2 (Hs01091564_m1), MCM7 (Hs00428518_m1), MCM10 (Hs00218560_m1), CDC6 (Hs00154374_m1), CDC45 (Hs00907337_m1), CDT1 (Hs00925491_g1), TOP3A (Hs00172806_m1), TOP3B (Hs00172728_m1), TOPBP1 (Hs00199775_m1), RECQL4 (Hs00171627_m1), GINS1 (Hs01040834_m1), GINS2 (Hs00211479_m1), GINS3 (Hs01090589_m1), GINS4 (Hs01077879_m1), TIPIN (Hs00762756_s1), CLSPN (Hs00898637_m1), WDHD1 (Hs00173172_m1), PCNA (Hs00427214_g1), POLA1 (Hs00213524_m1), POLD1 (Hs01100821_m1), POLE (Hs00923952_m1), BOD1L1 (Hs00386033_m1), and RFC1 (Hs01099126_m1). Following comprehensive analyses, expression levels of some genes were confirmed using separately prepared samples. Expression values were normalized to ACTB (Hs01060665_g1) levels, and relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Plasmids and transfection

Wild-type CARD14 cDNA (pFN21AE3344) was purchased from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute. To generate a CARD14-expressing vector (p3FLAG-CARD14wt) for transient overexpression, EGFP in pEGFP-C2 (Takara Bio) was replaced by the wild-type CARD14 gene obtained from pFN21AE3344 with N-terminal 3xFLAG tag peptides (DYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDK) (Sigma-Aldrich). To generate a CARD14-expressing vector (pTRE3G-Pur-3FLAG-CARD14wt) for the establishment of Tet-On 3G inducible cell lines, the wild-type CARD14 insert with N-terminal 3xFLAG tag was cloned into pBApo-EFα Pur DNA (Takara Bio) whose EF-1α promoter was replaced by TRE3G promoter obtained from pTRE3G (Clontech). The c.356T>C (p.Met119Thr) or c.407A>T (p.Gln136Leu) mutation was introduced to p3FLAG-CARD14wt and pTRE3G-Pur-3FLAG-CARD14wt using QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits (Agilent Technologies) (p3FLAG-CARD14-M119T /-Q136L or pTRE3G-Pur-3FLAG-CARD14-M119T /-Q136L, respectively). To establish Tet3G-expressing U2OS cells, pCMV-Tet3G (Clontech) was used. For the NF-κB-Luciferase Reporter assay, pNL1.1.PGK[Nluc/PGK] (Promega), pGL4.27[luc2P/minP/Hygro] (Promega), and pNL3.2.NF-κB-RE[NlucP/NF-κB-RE/Hygro] (Promega) were purchased, and pCMV4-3 HA/IkB-alpha was a gift from Warner Greene (Addgene, #21985). To generate firefly luciferase (Fluc)-expressing vector (pNL1.1.PGK[Fluc/PGK]) for transfection efficiency normalization, the Nanoluc luciferase (Nluc) gene in pNL1.1.PGK[Nluc/PGK] was replaced by the Fluc gene obtained from pGL4.27[luc2P/minP/Hygro]. pDRGFP (Addgene, #26475) and pCBASceI (Addgene, #26477) were gifts from Maria Jasin for the DR-GFP assay. To generate a wild-type EGFP-expressing vector (pDRGFPwt) for transfection efficiency normalization, the Sce-EGFP gene, which contains an I-SceI recognition sequence, was replaced by EGFP obtained from pEGFP-C2. All plasmids were transfected into U2OS or HaCaT cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or Xfect Transfection Reagent (Takara), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Establishment of the Tet-On 3G CARD14 inducible cell lines

The Tet-On 3G Inducible Expression System (Clontech) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to establish Tet-On 3G CARD14 inducible cell lines. Briefly, U2OS cells were first transfected with the pCMV-Tet3G plasmid and selected using 250 μg/mL G418 (Sigma-Aldrich). The G418-resistant clone was maintained as the Tet3G-expressing U2OS cell line. Tet3G-expressing U2OS cells were then transfected with pTRE3G-Pur-3FLAG-CARD14wt, pTRE3G-Pur-3FLAG-CARD14-M119T, or pTRE3G-Pur-3FLAG-CARD14-Q136L. Next, 0.75 μg/μL puromycin (GIBCO) was used for selection following which double-stable Tet-On 3G inducible cell lines were cloned by limiting the dilution technique. The cell lines of each genotype were tested for CARD14 expression in the presence of 500 ng/mL doxycycline (Dox) (Clontech), and clones with the highest fold induction were selected for further analyses.

Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy

Twenty-four hours after adding Dox into CARD14 inducible cell lines, or 24 h after transfection into U2OS or HaCaT cells, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 4°C and washed twice with PBS. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at 4°C and blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Wako) in PBS with 1% DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C, the cells were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted with 3% BSA in PBS for 60 min (primary antibodies) or for 30 min (secondary antibodies) at 37°C. Anti-FLAG M2 antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, F3165) were used as the primary antibodies for FLAG staining. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A11001) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A21244) were used as secondary antibodies. For F-actin staining, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min at 37°C between the primary and secondary antibody reactions. Nuclei were stained with DAPI during the blocking step. Fluorescence images were obtained with a BZ-X800 (Keyence) or FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus).

RNA interference

The following Silencer select siRNAs (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to knockdown genes of interest: NFKB1 (s9505), NFKB2 (s9508), RELA (s11915), RELB (s11917), REL (s11906), and Silencer Select Negative Control siRNA (4390843). The siRNAs were reverse transfected into cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and incubated for 24 h.

NF-κB-Luciferase Reporter assay

CARD14 inducible cell lines were co-transfected with pNL3.2.NF-κB-RE[NlucP/NF-κB-RE/Hygro] and pNL1.1.PGK[Fluc/PGK] in the absence or presence of Dox. To evaluate the effect of IκBα expression on the NF-κB signaling pathway, pCMV4-3 HA/IkB-alpha was overexpressed with pNL3.2.NF-κB-RE[NlucP/NF-κB-RE/Hygro] and pNL1.1.PGK[Fluc/PGK]. Luciferase activity of the lysates was measured using a Nano-Glo Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and SpectraMax Paradigm (Molecular Devices), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nluc activity derived from pNL3.2.NF-κB-RE[NlucP/NF-κB-RE/Hygro] was normalized to Fluc activity from pNL1.1.PGK[Fluc/PGK].

Western blotting

The whole-cell lysate was obtained by lysing cells in a mixture of NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and NuPAGE Sample Reducing Agent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lysate was sonicated with Handy Sonic UR-21P (TOMY), denatured for 10 min at 70°C, and fractionated on NuPAGE 4%–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by the transferring of resolved proteins onto PVDF membranes via an iBlot 2 Dry Blotting System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following blocking for 60 min with 1% BSA in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) or 5% skim milk in TBST, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the following primary antibodies: FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich, F3165), γH2AX (Millipore, 05-636), histone H3 (abcam, ab1791), RPA32 (RPA2) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-56770), phospho-RPA2 (Ser33) (Novus Biologicals, NB100-544), 53BP1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4937), phospho-53BP1 (Ser1778) (Cell Signaling Technology, 2675), BRCA1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-6954), phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1524) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9009), NFKB1 (abcam, ab32360), NFKB2 (abcam, ab109440), RELA (abcam, ab16502), RELB (Cell Signaling Technology, 4954), or REL (abcam, 133251). HRP-linked horse anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 7076) and HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074) were used as secondary antibodies. 20X LumiGLO Reagent and 20X Peroxide (Cell Signaling Technology) or SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used as substrates for the secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescence data were obtained with ImageQuant LAS 4000 (Fujifilm) and band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH).

DR-GFP assay (I-SceI induced DSB repair assay)

CARD14 inducible cell lines were used in a DR-GFP assay via transient transfection with pDRGFP and pCBASceI. Cells were harvested 72 h after transfection with these two plasmids, following which the number of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-positive cells was measured using FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) (30,000 cells per biological replicate were analyzed). Under these conditions, parallel transfection with the pDRGFPwt plasmid was used to determine transfection efficiency. All analyses were performed in the absence or presence of Dox. Cells not transfected with pCBASceI were used as negative control. A DR-GFP assay using U2OS cells which harbor chromosomally integrated EGFP reporter substrates was also conducted. To establish this cell line, U2OS cells were first transfected with pDRGFP plasmid, selected using 0.75 μg/μL puromycin and cloned via the limiting dilution technique (U2OS_DRGFP cells). U2OS_DRGFP cells were transfected with p3FLAG-CARD14-WT, p3FLAG-CARD14-M119T, or p3FLAG-CARD14-Q136L along with pCBASceI. Cells were harvested 72 h after transfection and the number of EGFP-positive cells were counted using FACSCanto II. HR efficiency was calculated as the ratio of EGFP-positive cells over total cells. Non-transfected cells were used as negative control. All flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

Cell cycle analysis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

To analyze cell cycle distribution, cells were pulse labeled with 10 μM EdU 30 min before harvest. EdU staining was performed using a Click-iT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was stained with FxCycle Violet (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Flow cytometry data of EdU-DNA content profiles were acquired with FACSCanto II and analyzed using FlowJo software.

FACS-based quantification of DNA damage and HR-related factor activity

Cells treated with or without HU were trypsinized and washed with 1% BSA in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with dilution buffer (0.5% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature with one or two of the following primary antibodies diluted with dilution buffer: γH2AX (Millipore, 05-636), phospho-RPA2 (Ser33) (Novus Biologicals, NB100-544), phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1524) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9009), or phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) (abcam, ab47318). After washing with dilution buffer, cells were subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and/or Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) as secondary antibodies. Genomic DNA was stained with FxCycle Violet. A gate was established for each factor using negative control samples stained with mouse IgG1 negative control antibodies (BIO-RAD, MCA928) or polyclonal rabbit IgG (R&D Systems, AB-105-C). In all analyses, signal intensities of 30,000 cells per biological replicate were measured using FACSCanto II and analyzed with FlowJo software.

DNA fiber assay

The DNA fiber assay was performed as described previously25 with slight modifications. Briefly, CARD14 inducible cell lines were labeled with 25 μM 5-chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU) (Sigma-Aldrich), washed with PBS, and exposed to 250 μM 5-iododeoxyuridine (IdU) (Sigma-Aldrich). To measure the efficiency of replication restart, cells were treated with 2 mM HU after CldU labeling and exposed to IdU. Labeled cells were harvested and resuspended in cold PBS. The cell suspension was mixed 1:4 with cell lysis solution (0.5% SDS, 50 mM EDTA, 200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]), placed on glass slides and carefully tilted at a 15° angle causing DNA fibers to spread into single molecules via gravity. Next, the DNA fibers were denatured by fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and immersing in 2.5 M HCl for 80 min at 27°C. Slides were neutralized and washed with PBS before blocking with 3% BSA in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. DNA fibers were then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in 3% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C (primary antibodies) or for 90 min at 37°C (secondary antibodies). Anti-BrdU antibodies (BU1/75 [ICR1]) (abcam, ab6326) for CldU and anti-BrdU antibodies (clone B44) (BD Biosciences, 347580) for IdU were used as primary antibodies. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) antibodies and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A11005) were used as secondary antibodies. Finally, slides were mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were obtained using a FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus) and all data were analyzed via Computer Assisted Scoring & Analysis (CASA) software purchased from Dr. Paul Chastain. Tracts containing CldU were pseudocolored in red, and tracts containing IdU in green. Replication fork speed was estimated using a conversion factor of 2.59 kb/μm.26

Sister chromatid exchange (SCE) assay

The SCE assay was carried out as previously described.27 Briefly, prior to the experiment, slides were immersed in 0.1 N HCl in 99.5% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature and washed thrice with 99.5% ethanol. After rinsing with distilled water, they were stored in distilled water at 4°C. Cells were incubated with 20 μM BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) for 42 h. During the last 2 h of BrdU incubation, cells were also treated with 0.2 μg/mL colcemid (Sigma-Aldrich). To examine the effects of replication stress, cells were incubated with BrdU for 20 h followed by 2 mM HU treatment for 36 h, incubated again with BrdU for 24 h and treated with colcemid for the last 2 h. Cells were collected by mitotic shake-off, washed in PBS, and swollen in 7 mL of hypotonic solution (46.5 mM KCl, 8.5 mM Na × Citrate) for 13 min at 37°C. After the incubation, 2 mL of freshly prepared 3:1 methanol-acetic acid fixative was added and mixed by gently inverting the tube. The tubes were centrifuged for 3 min at 200 × g at room temperature and the supernatant was aspirated. The cell pellets were resuspended with 4 mL of fixative and incubated for 20 min at 4°C. Following fixation, cells were resuspended in a minimal amount of fixative. Metaphase cells were then spread on the chilled slides described above and completely dried at room temperature. Slides were stained for 30 min at room temperature with 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich) in Sorensen’s phosphate buffer (0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.1 M KH2PO4 [pH 6.8]). After washing with Sorensen buffer, the slides were covered with Sorensen buffer and exposed to UV light for 60 min at 55°C, following which the slides were immersed in 1× SSC buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), incubated for 60 min at 50°C and finally stained with 10% Giemsa (Wako) in Sorensen buffer for 30 min at room temperature. After washing thrice with water, the coverslips were mounted on the slides using MOUNT-QUICK (Funakoshi). Images were obtained via BZ-X800 (Keyence) using CFI Plan Apo λ 100 × H objective lens. A minimum of 25 images were randomly captured for each condition and the number of SCEs per chromosome was scored.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical parameters are shown in each figure and the corresponding legends. Two-tailed t tests or one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons were used to compare means of normally distributed data; whereas two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests were used for comparison of non-normally distributed data. All statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad) and the threshold for defining statistical significance was p < 0.05.

Results

Identification of revertant mosaicism in pityriasis rubra pilaris type V

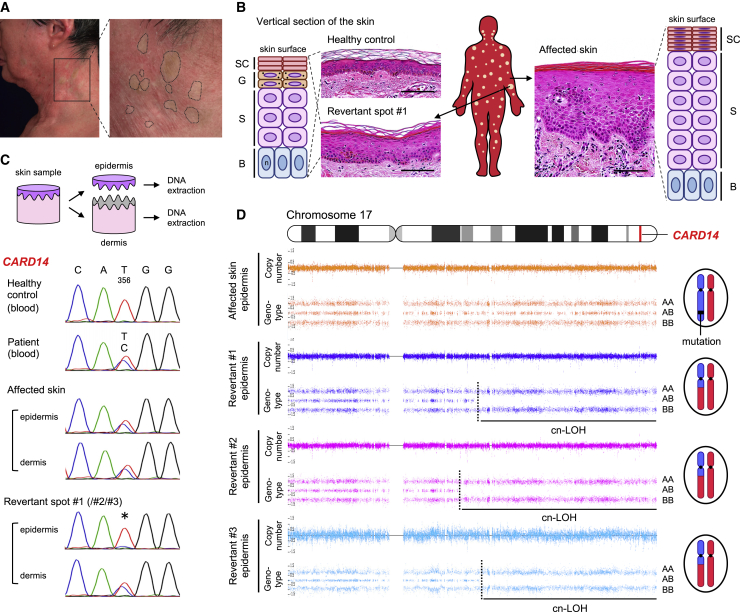

We analyzed two unrelated Japanese individuals with PRPV presenting with erythroderma (generalized red skin) since birth. Individual 1, a 60-year-old man, and individual 2, a 27-year-old woman,28 were heterozygous for c.356T>C (p.Met119Thr) and c.407A>T (p.Gln136Leu) in CARD14, respectively (Figures S1A–S1F). We noted numerous disseminated normal-appearing skin areas in individual 1 and several clinically unaffected spots on the left leg in individual 2 (Figures 1A and S1G–S1K). A skin biopsy revealed that these spots were histologically normalized (Figures 1B and S1L–S1N). Notably, the mutations reverted to wild-type in the epidermis of all examined spots (6 of 6) but not in the dermis (Figures 1C and S2A). To address the mechanisms underlying this reversion, we performed a whole-genome oligo-SNP array analysis using genomic DNA from each epidermis. Notably, copy-neutral LoH (cn-LoH), extending from breakpoints proximal to CARD14, to the telomere on chromosome 17q, were identified in 4 of 6 revertant spots (Figures 1D, S2B, and S2C). Varying initiation sites of cn-LoH excluded the possibility of simple genetic mosaicism. Notably, 1 of 3 revertant spots in individual 1 showed a different cn-LoH on chromosome 9q (Figure S2D). Furthermore, individual 1 had developed multiple skin tumors,29,30 including squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) which harbor chromosomal aberrations, such as LoH and trisomy (Figures S2E and S2F). Because HR events that are generally rare in most genetic skin diseases were frequently observed in these PRPV individuals, we inferred that mut-CARD14 may induce an increase in the rate of HR, which potentially leads to RM and carcinogenesis (Figure S1O).

Figure 1.

Clinical, histological, and genetic features of individual 1

(A) Clinically normalized skin spots on the left lateral neck of individual 1. Dotted circles represent the areas suspected of containing revertant spots.

(B) Histological and schematic comparison among healthy control skin, affected skin, and revertant spots. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Scale bars, 100 μm. SC, stratum corneum; G, granular layer; S, spinous layer; B, basal layer; n, nucleus. See also Figures S1L–S1N.

(C) Skin sample processing and mutation analysis of CARD14 using genomic DNA. The missense mutation, c.356T>C, is absent in the revertant epidermis (∗).

(D) SNP array data of chromosome 17 in individual 1. Cn-LoH was identified in all revertant epidermis samples examined in this study. The dotted lines represent recombination breakpoints.

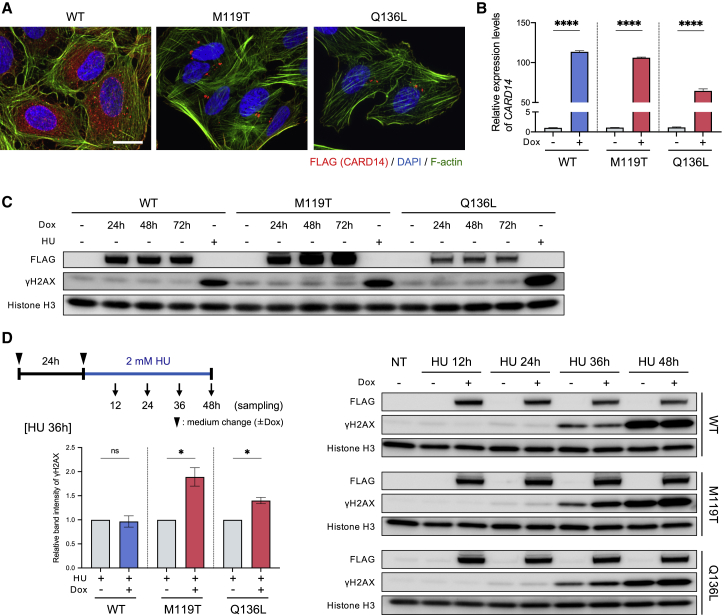

No direct effect of mutant CARD14 on DNA damage response

To examine the effects of mut-CARD14 on HR, we generated U2OS cell lines which express FLAG-tagged wild-type (wt-), or mut-CARD14, only when Dox is present (Figures 2A, 2B, and S3). To determine whether mut-CARD14 directly increases DSBs, the levels of phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX), a major marker of large chromatin domains surrounding DSBs, were quantified in these cell lines. However, no significant increase in γH2AX levels was detected in any of the cell lines following Dox stimulation (Figure 2C). To address whether mut-CARD14 alters DNA damage response (DDR) to exogenous DSBs, we monitored γH2AX levels as well as the phosphorylation levels of 53BP1 and RPA2, markers for non-homologous end joining and HR, respectively,31, 32, 33 after exposing the cell lines to IR or etoposide. Mut-CARD14 did not enhance HR in the repair of exogenous DSBs (Figure S4). To further examine whether mut-CARD14 increases HR in DDR, we performed EGFP-based reporter assay in which a DSB induced by the endonuclease I-SceI followed by HR leads to generation of EGFP-positive cells (Figure S5A).34 Again, neither wt-CARD14 nor mut-CARD14 caused a significant increase in HR frequency (Figures S5B–S5F). These findings suggest that mut-CARD14 does not preferentially increase either DNA damage or HR frequency in the DSB repair pathway.

Figure 2.

Mut-CARD14 expression alters the replication stress response

(A) Intracellular distribution of CARD14 by immunofluorescence. Mut-CARD14 formed aggregates in the perinuclear region, while wt-CARD14 was diffused in the cytoplasm. Scale bar, 25 μm.

(B) Gene expression levels of CARD14 analyzed by qPCR. CARD14 inducible cell lines were incubated in the presence or absence of Dox for 24 h. The results were normalized to ACTB expression; n = 3 independent experiments; error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed t test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(C) CARD14 inducible cell lines were incubated in the presence of Dox for the indicated time periods. Whole-cell lysate was immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. HU-treated samples were used as positive controls exhibiting high levels of γH2AX.

(D) Schematic of cells being treated with 2 mM HU and immunoblots showing the levels of DNA damage following HU treatment. Prolonged HU treatment increased γH2AX in the presence of mut-CARD14. The relative band intensities of γH2AX following 36 h HU treatment are also shown; n = 3 independent experiments; error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed t test. ∗p < 0.05; ns, not significant. NT, non-treatment; WT, wild-type; M119T, p.Met119Thr; Q136L, p.Gln136Leu.

Mutant CARD14 alters replication stress response

Replication stress, especially following prolonged stalling, may cause DNA replication fork collapse, leading to DSBs.3 HR promotes the restart of stress-induced stalled and collapsed replication forks.5 Therefore, we next sought to address whether mut-CARD14 causes replication stress and alters RSR. To this end, we first performed FACS-based cell cycle analysis using the U2OS cell lines. However, mut-CARD14 did not alter cell cycle distribution (Figures S6A and S6B). This was further confirmed via DNA fiber analysis, in which mut-CARD14 neither affected fork speed nor increased stalled fork frequency (Figures S6C-S6G). Thus, mut-CARD14 did not result in replication stress per se.

To address whether mut-CARD14 increases DSBs under conditions of replication stress, we treated the cell lines with HU and monitored γH2AX levels up to 48 h after treatment. Notably, mut-CARD14 cell lines with Dox showed higher levels of γH2AX than those without Dox at 36 h and 48 h, whereas wt-CARD14 cell lines showed no difference at any of the time points (Figure 2D). We performed the same analysis using APH, which also caused similar differences in γH2AX levels based on mut-CARD14 expression (Figure S6H). In both analyses, no obvious difference in γH2AX levels was detected 24 h following treatment with HU or APH. Collectively, these results suggest that mut-CARD14 expression leads to fork instability following prolonged replication fork stalling but does not increase DSBs following short-term fork stalling.

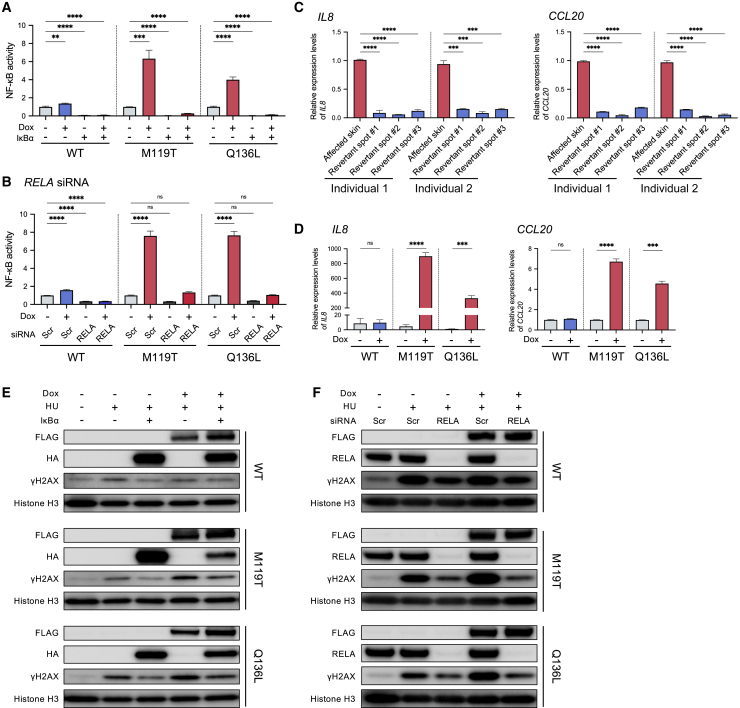

The activated NF-κB signaling pathway is partially attributable to altered replication stress response

As the aberrantly activated NF-κB pathway has been reported to play an important role in the pathophysiology of PRPV,20 we also confirmed that the above two CARD14 mutations activate the NF-κB pathway (Figures 3A and 3B). Moreover, gene expression levels of IL8 and CCL20, which encode inflammatory chemokines related to the NF-κB pathway and PRPV,35 were markedly different between affected skin and revertant spots (Figure 3C) and also differed between cells collected before and after mut-CARD14 expression (Figure 3D), indicating the significance of this pathway in PRPV.

Figure 3.

NF-κB signaling activity affects the replication stress response

(A) NF-κB-dependent luciferase assay using CARD14-inducible cell lines with or without IκBα overexpression; n = 6 independent experiments; error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons test. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(B) NF-κB-dependent luciferase assay using CARD14-inducible cell lines with or without RELA depletion; n = 5 independent experiments; error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

(C) Gene expression levels of IL8 (left) and CCL20 (right) in whole skin samples taken from affected areas and revertant spots. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons test. Error bars represent SD. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(D) Gene expression levels of IL8 (left) and CCL20 (right). CARD14-inducible cell lines were incubated with or without Dox for 24 h. The results were normalized to ACTB expression. n = 3 independent experiments; error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed t test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

(E) Whole-cell lysate from HU-treated cells, with or without IκBα overexpression, was immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. IκBα expression reduced γH2AX levels in cells expressing mut-CARD14.

(F) Whole-cell lysate from RELA-depleted cells treated with HU was immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. RELA depletion reduced γH2AX levels in cells expressing mut-CARD14. WT, wild-type; M119T, p.Met119Thr; Q136L, p.Gln136Leu; Scr, scramble (negative control).

To clarify whether mut-CARD14-induced stalled fork instability is mediated by the NF-κB pathway, we first confirmed that mut-CARD14-induced NF-κB activation was suppressed by overexpression of the inhibitor of κBα (IκBα) (Figure 3A). Furthermore, although the NF-κB family in mammals comprises five proteins, namely, NFKB1 (p105/p50), NFKB2 (p100/p52), RELA (p65), RELB, and REL (c-Rel),36 only cells depleted of RELA by RNA interference exhibited inhibition of mut-CARD14-induced NF-κB activation (Figures 3B and S7A–S7D). We then examined γH2AX levels in HU-treated cell lines, with or without IκBα overexpression or RELA RNA interference (Figures S7E and S7F). Notably, both IκBα overexpression and RELA knockdown partially reduced γH2AX levels in cells expressing mut-CARD14 (Figures 3E and 3F). Meanwhile, although the NF-κB pathway was activated in U2OS cells by TNFα (Figure S7G), no significant difference was observed in γH2AX levels between TNFα-treated and non-treated samples at any time point following HU stimulation (Figure S7H). Taken together, these results suggest that mut-CARD14-induced alteration of RSR is partially explained by activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway; however, other mut-CARD14-related pathways may also be involved.

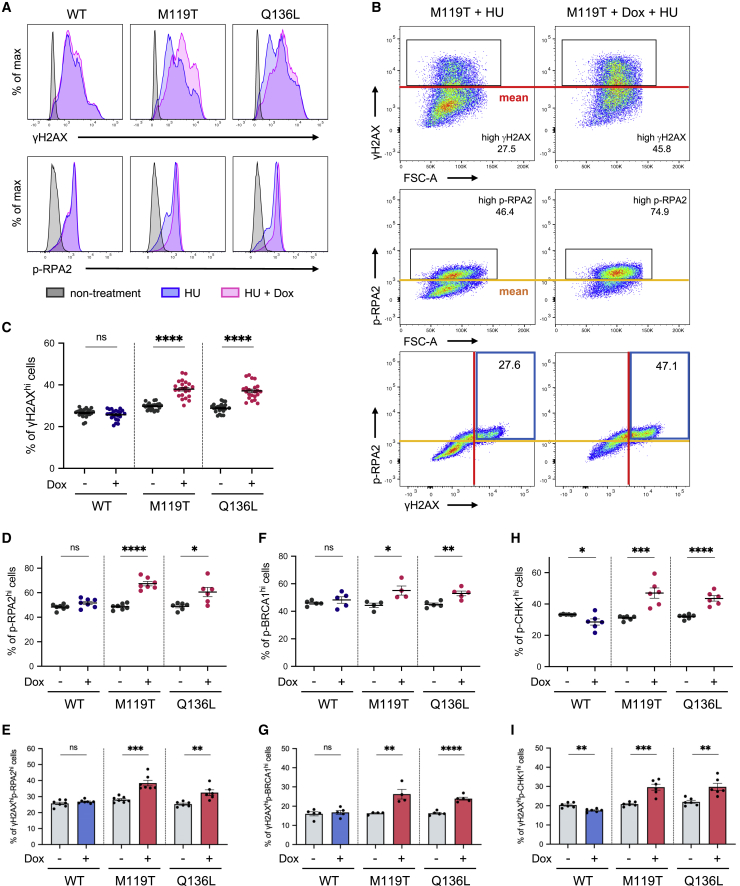

Homologous recombination is activated by mutant CARD14

Having confirmed that mut-CARD14 expression decreases fork stability under prolonged replication stress, we next sought to investigate whether HR-related factors are activated under these circumstances. We approached this issue using a FACS-based method to quantify the activities of HR-related factors at the single-cell level.37,38 For these analyses, the mean values of signal intensities obtained from HU-treated and Dox-absent samples were set to threshold levels and the percentages of cells showing intensities above these levels (γH2AXhi cells) were compared among samples (Figures 4A, 4B, and S8A). Notably, consistent with immunoblotting data, mut-CARD14 cell lines treated with Dox and either HU or APH for 36 h showed a significant increase in the percentage of γH2AXhi cells among the total cells, compared to those not treated with Dox, whereas wt-CARD14 showed no such increase (Figures 4C and S8B–S8D). Similarly, under prolonged replication stress, mut-CARD14 expression significantly increased the ratio of highly phosphorylated RPA2 cells (p-RPA2hi cells) (Figure 4D). Furthermore, co-staining with γH2AX and p-RPA2 revealed that mut-CARD14 expression increased the proportion of double-positive cells (γH2AXhip-RPA2hi cells) (Figures 4B and 4E). We also identified that mut-CARD14 activated BRCA1, which is important for HR and fork restart,39 yielding a higher proportion of γH2AXhip-BRCA1hi cells (Figures 4F and 4G).

Figure 4.

FACS-based analyses of HR-related factors

(A) Expression of γH2AX (upper panels) and p-RPA2 (lower panels) in CARD14 inducible cell lines. Each panel is a representative histogram showing comparison between non-treatment and 2 mM HU treatment for 36 h with or without Dox.

(B) Red and yellow lines are the threshold levels which were determined based on the mean values of signal intensities obtained from HU-treated and Dox-absent cells. The numbers in the upper and middle panels represent the percentage of γH2AXhi or p-RPA2hi cells, and those in the blue boxes in the lower panels represent γH2AXhip-RPA2hi cells.

(C) Comparison of the percentage of γH2AXhi cells; n = 23 (WT) or 22 (M119T/Q136L) independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM.

(D, F, and H) Comparison of the percentage of p-RPA2hi (D), p-BRCA1hi (F), and p-CHK1hi cells (H).

(E, G, and I) Comparison of the percentage of γH2AXhip-RPA2hi cells (E), γH2AXhip-BRCA1hi cells (G), and γH2AXhip-CHK1hi cells (I).

n = 4–7 independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using the two-tailed t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant. WT, wild-type; M119T, p.Met119Thr; Q136L, p.Gln136Leu.

We further examined whether the ATR-CHK1 pathway, which stabilizes replication forks and promotes several types of fork restarts including an HR-mediated fork restart in RSR,40 is activated by mut-CARD14 under prolonged fork stalling. Mut-CARD14 significantly increased the proportion of γH2AXhip-CHK1hi cells as well as that of p-CHK1hi cells (Figures 4H and 4I). Collectively, these results suggest that, in mut-CARD14-expressing cells, collapsed forks caused by prolonged stalling were repaired by the HR-mediated pathway via activation of the ATR-CHK1 signaling pathway.

Mutant CARD14 promotes break-induced replication in replication stress response

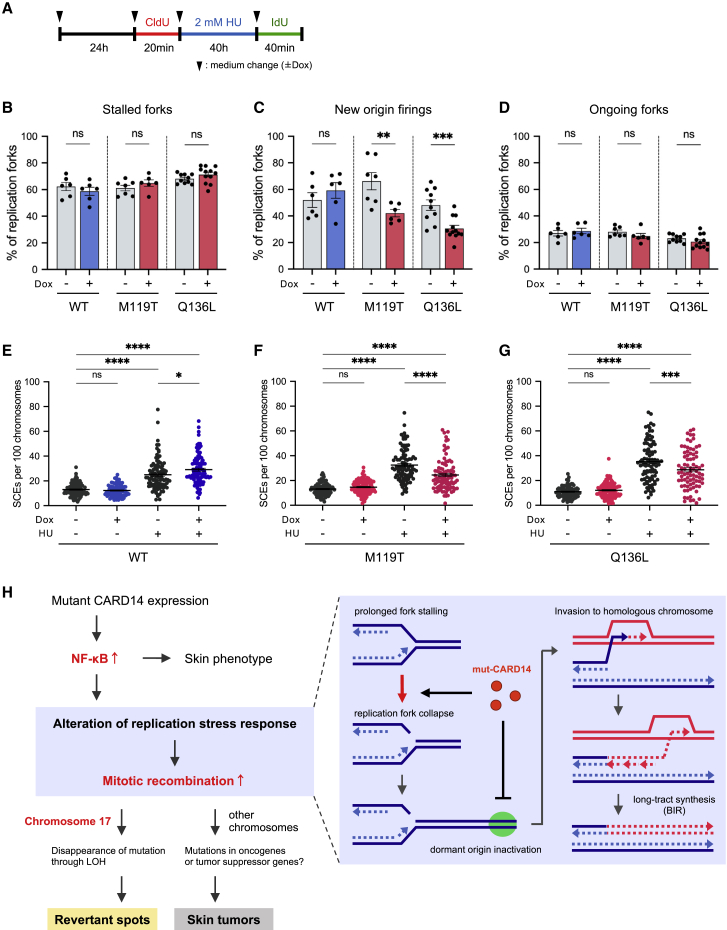

HR-mediated repair of stalled or collapsed forks may take place via three pathways: synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), double Holliday junction (dHJ), and BIR6,41 (Figure S9A). BIR is initiated when only one broken end is available for strand invasion, whereas SDSA and dHJ require two DSB ends. Thus, dormant origin firing is essential for rescuing collapsed forks using these two pathways.41 Hence, we sought to determine which pathway plays a dominant role in replication fork repair under mut-CARD14 expression. To this end, we first performed qPCR analysis of replication-related genes. The expression levels of genes associated with replication origin firing, such as ORC1, MCM10, GINS1, and GINS2, were decreased in mut-CARD14-expressing cells following extended HU treatment, but not in wt-CARD14-expressing cells (Figure S10). To further confirm whether mut-CARD14 suppresses new origin firing after prolonged fork stalling, we analyzed replication fork dynamics via DNA fiber assay with prolonged HU treatment. The frequency of new origin firing was reduced by mut-CARD14 expression but not by wt-CARD14, while neither wt- nor mut-CARD14 altered the frequency of stalled or ongoing replication forks (Figures 5A–5D). Moreover, the difference in the frequency of new origin firings was diminished by IκBa overexpression and RELA depletion (Figures S11), further highlighting the role of the NF-κB signaling pathway in the mut-CARD14-induced alteration of RSR. As these findings suggested that mut-CARD14 expression, together with HU, inhibits dormant origin firings near collapsed forks, resulting in a situation where only one broken end is available for DSB repair, we concluded that mut-CARD14 promotes BIR in stalled or collapsed fork repair under conditions of replication stress (Figure S9B).

Figure 5.

Mut-CARD14 expression suppresses dormant origin firings and promotes BIR

(A) Schematic depicting timeline of when cells were labeled with CldU and IdU in the presence of HU treatment.

(B–D) Quantification of the percentage of stalled forks (B), new origin firings (C), and ongoing forks (D) to all CldU-labeled forks; n = 6–12 independent experiments; error bars represent SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using the two-tailed t test.

(E–G) Quantification of SCE formation in cells treated with or without HU. Quantification of SCE formation in cells treated with or without 2 mM HU for 36 h. For each condition, 27–35 metaphase cells were analyzed and each data point represents the number of SCEs per 100 chromosomes per metaphase spread. Data from three experiments were pooled. Horizontal lines represent mean values ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by a multiple comparisons test.

(H) A model of the mechanism underlying mitotic recombination induced by mut-CARD14 expression. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant. WT, wild-type; M119T, p.Met119Thr; Q136L, p.Gln136Leu.

Notably, HR-mediated revertant epidermis samples, as well as SCC samples, obtained from the studied PRPV individuals, all possessed long-tract LoH extending from recombination sites to the telomere (Figures 1D, S2B, and S2D–S2F). Although this specific form of LoH arises only via BIR or dHJ with crossover resolution (Figure S9C), other possible consequences of dHJ, such as gene conversion, were not detected in any of the samples. Furthermore, the frequency of SCEs,42 which represents the crossover events, following HU treatment was somewhat decreased in mut-CARD14-expressing cells, but not in those expressing wt-CARD14 (Figures 5E–5G), suggesting that dHJ with crossover does not mainly occur in this context. Considering the results together, we deduced that mut-CARD14 plays a role in the reversion of a disease-causing mutation in individuals with PRPV by enhancing BIR under conditions of replication stress (Figure 5H).

Discussion

The current study revealed that RM occurs in PRPV. We demonstrated that HR is the major mechanism responsible for the reversion of CARD14 mutations and that mut-CARD14 preferentially drives BIR under conditions of replication stress. However, BIR is generally regarded as a rare event which is suppressed by MUS81 endonuclease in normal cells, as well as converging forks arriving from the opposite direction, as it elevates the risk of mutagenesis and chromosomal abnormalities.43 Notably, recent studies have uncovered a series of unusual BIR-promoting circumstances as follows:41,44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 (1) generation of DNA nicks in genomic regions lacking replication origins within a MUS81-null background, (2) repair of massive replication fork collapse under conditions of replication stress (e.g., overexpression of oncogenes, deregulation of origin licensing, inverted DNA repeats, trinucleotide repeats, and R-loops), and (3) alternative lengthening of telomeres in the absence of telomerase. Our findings suggest that mut-CARD14 promotes replication fork collapse and suppresses dormant origin firing in the replication stress state. These effects of mut-CARD14 collectively promote BIR that may continue for hundreds of kilobases, resulting in long-tract LoH that extends to the telomere. Therefore, this study provides evidence indicating the potential contribution of BIR to RM. Notably, similar long-tract LoH has also been frequently observed in other skin diseases such as ichthyosis with confetti (MIM: 609165) and loricrin keratoderma (MIM: 604117) where dozens to thousands of HR-driven revertant skin spots arise in each individual.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Further investigations centered on RM may help elucidate hitherto unknown or unvalued mechanisms that regulate the BIR pathway.

This study also suggests that skin inflammation, such as that induced by mut-CARD14, may promote BIR. Notably, individuals with X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency (MIM: 300291), resulting from gain-of-function mutations in IKBKG (MIM: 300248), showed a high frequency of somatic revertant mosaicism particularly in T cells, which suggests the possible role of the aberrant activation of NF-κB signaling in the mutation-reversion events.50 In addition, recent studies on individuals with ulcerative colitis (MIM: 266600) have revealed that human intestinal stem cells exposed to long-standing inflammation adapt to such inflammation by acquiring genetic and genomic alterations including LoH, associated with the downregulation of IL-17 signaling.8,9 Furthermore, long-tract LoH is frequently seen in skin lesions of porokeratosis (MIM: 175900, 614714),51 a common autoinflammatory keratinization disease.52 Interestingly, previous studies have shown that it is replication stress, and not I-SceI-induced DSB, which activates the NF-κB signaling pathway, which, in turn, induces HR.53 The current study indicated that mut-CARD14 does not promote HR when DSBs are exogenously introduced via I-SceI but rather drives BIR under conditions of replication stress. These findings suggest that inflammation resulting from NF-κB activation under conditions of replication stress may induce BIR. Further studies are warranted to address the involvement of inflammation in BIR initiation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that RM can occur in PRPV and implicates the involvement of BIR in reversion events. However, as our data are based exclusively on the analyses of two PRPV-affected individuals, further studies are warranted to determine whether this phenomenon occurs in all PRPV-affected individuals. Furthermore, other potential mechanisms underlying RM should also be investigated. Fully elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying natural gene therapy may deepen the understanding of DDR or RSR and pave the way for the development of innovative therapies for genetic diseases, for which therapeutic options are currently limited, by manipulating HR to repair disease-causing mutations.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We are most indebted to the individuals and their family members for their participation in this study. This work was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers JP19H03679 and JP17H06271 to T.N. and H.S., respectively), the Terumo Foundation for Life Sciences and Arts (grant number 16-II 330 to T.N.), the Rohto Dermatology Research Award (to T.N.), the Akiyama Life Science Foundation (to T.N.), the Nakatomi Foundation (to T.N.), the Ichiro Kanehara Foundation (to T.N.), the Takeda Science Foundation (to T.N.), the Geriatric Dermatology Research Grant (to T.N.), and the Northern Advancement Center for Science & Technology (NOASTEC) Foundation (grant number H28 T-1-42 to T.N.).

Published: May 17, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.04.021.

Data and code availability

The data about our affected subjects are available on request due to privacy or other restrictions. All the other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Web resources

1000 Genomes Project, https://www.internationalgenome.org/home

OMIM, https://omim.org/

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Khanna K.K., Jackson S.P. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:247–254. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazouzi A., Velimezi G., Loizou J.I. DNA replication stress: causes, resolution and disease. Exp. Cell Res. 2014;329:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeman M.K., Cimprich K.A. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:2–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petermann E., Orta M.L., Issaeva N., Schultz N., Helleday T. Hydroxyurea-stalled replication forks become progressively inactivated and require two different RAD51-mediated pathways for restart and repair. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petermann E., Helleday T. Pathways of mammalian replication fork restart. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nrm2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jasin M., Rothstein R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a012740. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng G., Lu Y., Zlotnikov G., Thor A.D., Smith H.S. Loss of heterozygosity in normal tissue adjacent to breast carcinomas. Science. 1996;274:2057–2059. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakiuchi N., Yoshida K., Uchino M., Kihara T., Akaki K., Inoue Y., Kawada K., Nagayama S., Yokoyama A., Yamamoto S. Frequent mutations that converge on the NFKBIZ pathway in ulcerative colitis. Nature. 2020;577:260–265. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1856-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nanki K., Fujii M., Shimokawa M., Matano M., Nishikori S., Date S., Takano A., Toshimitsu K., Ohta Y., Takahashi S. Somatic inflammatory gene mutations in human ulcerative colitis epithelium. Nature. 2020;577:254–259. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1844-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonkman M.F., Pasmooij A.M.G. Revertant mosaicism--patchwork in the skin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1680–1682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0809896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revy P., Kannengiesser C., Fischer A. Somatic genetic rescue in Mendelian haematopoietic diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:582–598. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomura T. Recombination-induced revertant mosaicism in ichthyosis with confetti and loricrin keratoderma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020;97:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choate K.A., Lu Y., Zhou J., Choi M., Elias P.M., Farhi A., Nelson-Williams C., Crumrine D., Williams M.L., Nopper A.J. Mitotic recombination in patients with ichthyosis causes reversion of dominant mutations in KRT10. Science. 2010;330:94–97. doi: 10.1126/science.1192280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choate K.A., Lu Y., Zhou J., Elias P.M., Zaidi S., Paller A.S., Farhi A., Nelson-Williams C., Crumrine D., Milstone L.M., Lifton R.P. Frequent somatic reversion of KRT1 mutations in ichthyosis with confetti. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1703–1707. doi: 10.1172/JCI64415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki S., Nomura T., Miyauchi T., Takeda M., Nakamura H., Shinkuma S., Fujita Y., Akiyama M., Shimizu H. Revertant Mosaicism in Ichthyosis with Confetti Caused by a Frameshift Mutation in KRT1. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2016;136:2093–2095. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomura T., Suzuki S., Miyauchi T., Takeda M., Shinkuma S., Fujita Y., Nishie W., Akiyama M., Shimizu H. Chromosomal inversions as a hidden disease-modifying factor for somatic recombination phenotypes. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e97595. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki S., Nomura T., Miyauchi T., Takeda M., Fujita Y., Nishie W., Akiyama M., Ishida-Yamamoto A., Shimizu H. Somatic recombination underlies frequent revertant mosaicism in loricrin keratoderma. Life Sci Alliance. 2019;2:e201800284. doi: 10.26508/lsa.201800284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths W.A.D. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: the problem of its classification. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1992;26:140–142. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roenneberg S., Biedermann T. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: algorithms for diagnosis and treatment. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018;32:889–898. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuchs-Telem D., Sarig O., van Steensel M.A.M., Isakov O., Israeli S., Nousbeck J., Richard K., Winnepenninckx V., Vernooij M., Shomron N. Familial pityriasis rubra pilaris is caused by mutations in CARD14. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan C.T., Cao L., Roberson E.D.O., Pierson K.C., Yang C.F., Joyce C.E., Ryan C., Duan S., Helms C.A., Liu Y. PSORS2 is due to mutations in CARD14. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wullaert A., Bonnet M.C., Pasparakis M. NF-κB in the regulation of epithelial homeostasis and inflammation. Cell Res. 2011;21:146–158. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemmensen A., Thomassen M., Clemmensen O., Tan Q., Kruse T.A., Petersen T.K., Andersen F., Andersen K.E. Extraction of high-quality epidermal RNA after ammonium thiocyanate-induced dermo-epidermal separation of 4 mm human skin biopsies. Exp. Dermatol. 2009;18:979–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tammaro M., Barr P., Ricci B., Yan H. Replication-dependent and transcription-dependent mechanisms of DNA double-strand break induction by the topoisomerase 2-targeting drug etoposide. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieminuszczy J., Schwab R.A., Niedzwiedz W. The DNA fibre technique - tracking helicases at work. Methods. 2016;108:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson D.A., Pombo A. Replicon clusters are stable units of chromosome structure: evidence that nuclear organization contributes to the efficient activation and propagation of S phase in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:1285–1295. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stults D.M., Killen M.W., Pierce A.J. The sister chromatid exchange (SCE) assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1105:439–455. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-739-6_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeichi T., Sugiura K., Nomura T., Sakamoto T., Ogawa Y., Oiso N., Futei Y., Fujisaki A., Koizumi A., Aoyama Y. Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris Type V as an Autoinflammatory Disease by CARD14 Mutations. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:66–70. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arita K., Akiyama M., Tsuji Y., Iwao F., Kodama K., Shimizu H. Squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with non-bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003;148:367–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05097_5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natsuga K., Akiyama M., Kato N., Sakai K., Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y., Nishimura M., Hata H., Abe M., Arita K., Tsuji-Abe Y. Novel ABCA12 mutations identified in two cases of non-bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma associated with multiple skin malignant neoplasia. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:2669–2673. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Symington L.S., Gautier J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:247–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panier S., Boulton S.J. Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byrne B.M., Oakley G.G. Replication protein A, the laxative that keeps DNA regular: The importance of RPA phosphorylation in maintaining genome stability. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;86:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierce A.J., Johnson R.D., Thompson L.H., Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2633–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akiyama M., Takeichi T., McGrath J.A., Sugiura K. Autoinflammatory keratinization diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;140:1545–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Q., Lenardo M.J., Baltimore D. 30 Years of NF-κB: A Blossoming of Relevance to Human Pathobiology. Cell. 2017;168:37–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shibata A., Moiani D., Arvai A.S., Perry J., Harding S.M., Genois M.-M., Maity R., van Rossum-Fikkert S., Kertokalio A., Romoli F. DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice is directed by distinct MRE11 nuclease activities. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forment J.V., Jackson S.P. A flow cytometry-based method to simplify the analysis and quantification of protein association to chromatin in mammalian cells. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:1297–1307. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y., Ning S., Wei Z., Xu R., Xu X., Xing M., Guo R., Xu D. 53BP1 and BRCA1 control pathway choice for stalled replication restart. eLife. 2017;6:e30523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saldivar J.C., Cortez D., Cimprich K.A. The essential kinase ATR: ensuring faithful duplication of a challenging genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:622–636. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kramara J., Osia B., Malkova A. Break-Induced Replication: The Where, The Why, and The How. Trends Genet. 2018;34:518–531. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson D.M., 3rd, Thompson L.H. Molecular mechanisms of sister-chromatid exchange. Mutat. Res. 2007;616:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayle R., Campbell I.M., Beck C.R., Yu Y., Wilson M., Shaw C.A., Bjergbaek L., Lupski J.R., Ira G. DNA REPAIR. Mus81 and converging forks limit the mutagenicity of replication fork breakage. Science. 2015;349:742–747. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lydeard J.R., Jain S., Yamaguchi M., Haber J.E. Break-induced replication and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance require Pol32. Nature. 2007;448:820–823. doi: 10.1038/nature06047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anand R.P., Lovett S.T., Haber J.E. Break-induced DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a010397. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramara J., Osia B., Malkova A. Break-induced replication: an unhealthy choice for stress relief? Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:11–12. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakofsky C.J., Malkova A. Break induced replication in eukaryotes: mechanisms, functions, and consequences. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017;52:395–413. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2017.1314444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim J.C., Harris S.T., Dinter T., Shah K.A., Mirkin S.M. The role of break-induced replication in large-scale expansions of (CAG)n/(CTG)n repeats. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macheret M., Halazonetis T.D. Intragenic origins due to short G1 phases underlie oncogene-induced DNA replication stress. Nature. 2018;555:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature25507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawai T., Nishikomori R., Izawa K., Murata Y., Tanaka N., Sakai H., Saito M., Yasumi T., Takaoka Y., Nakahata T. Frequent somatic mosaicism of NEMO in T cells of patients with X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency. Blood. 2012;119:5458–5466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kubo A., Sasaki T., Suzuki H., Shiohama A., Aoki S., Sato S., Fujita H., Ono N., Umegaki-Arao N., Kawai T. Clonal Expansion of Second-Hit Cells with Somatic Recombinations or C>T Transitions Form Porokeratosis in MVD or MVK Mutant Heterozygotes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2019;139:2458–2466.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akiyama M. Autoinflammatory Keratinization Diseases (AiKDs): Expansion of Disorders to Be Included. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volcic M., Karl S., Baumann B., Salles D., Daniel P., Fulda S., Wiesmüller L. NF-κB regulates DNA double-strand break repair in conjunction with BRCA1-CtIP complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:181–195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data about our affected subjects are available on request due to privacy or other restrictions. All the other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.