Abstract

Recent infectious disease outbreaks, such as COVID-19 and Ebola, have highlighted the need for rapid and accurate diagnosis to initiate treatment and curb transmission. Successful diagnostic strategies critically depend on the efficiency of biological sampling and timely analysis. However, current diagnostic techniques are invasive/intrusive and present a severe bottleneck by requiring specialist equipment and trained personnel. Moreover, centralised test facilities are poorly accessible and the requirement to travel may increase disease transmission. Self-administrable, point-of-care (PoC) microneedle diagnostic devices could provide a viable solution to these problems. These miniature needle arrays can detect biomarkers in/from the skin in a minimally invasive manner to provide (near-) real-time diagnosis. Few microneedle devices have been developed specifically for infectious disease diagnosis, though similar technologies are well established in other fields and generally adaptable for infectious disease diagnosis. These include microneedles for biofluid extraction, microneedle sensors and analyte-capturing microneedles, or combinations thereof. Analyte sampling/detection from both blood and dermal interstitial fluid is possible. These technologies are in their early stages of development for infectious disease diagnostics, and there is a vast scope for further development. In this review, we discuss the utility and future outlook of these microneedle technologies in infectious disease diagnosis.

KEY WORDS: Microneedle, Infectious disease, Point-of-care diagnostics (PoC), Biomarker detection, Skin, Biosensor, COVID-19

Abbreviations: AC, alternating current; APCs, antigen-presenting cells; ASSURED, affordable, sensitive, specific, user-friendly, rapid and robust, equipment-free and deliverable to end-users; cfDNA, cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid; CMOS, complementary metal-oxide semiconductor; COVID, coronavirus disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computerised tomography; CV, cyclic voltammetry; DC, direct current; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DPV, differential pulse voltammetry; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EDC/NHS, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminoproply) carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GOx, glucose oxidase; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, iontophoresis; ISF, interstitial fluid; JEV, Japanese encephalitis virus; MN, microneedle; NA, nucleic acid; OBMT, one-touch-activated blood multidiagnostic tool; OPD, o-phenylenediamine; PCB, printed circuit board; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane; PEDOT, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene); PNA, peptide nucleic acid; PoC, point-of-care; PP, polyphenol; PPD, poly(o-phenylenediamine); SALT, skin-associated lymphoid tissue; SAM, self-assembled monolayer; SEM, scanning electron microscope; SERS, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy; SWV, square wave voltammetry; TB, tuberculosis; UV, ultraviolet; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WHO, World Health Organisation

Graphical abstract

This review focused on the functionality of microneedle-based devices and their potential for medical diagnostics.

1. Introduction

Infectious diseases are commonly diagnosed using a combination of clinical examination (based on signs and symptoms) and laboratory testing (e.g., cell culture and molecular diagnostics)1. Clinical examination is challenging because different diseases often manifest with similar signs and symptoms2, 3, 4. On the other hand, laboratory testing allows disease-specific biomarkers to be identified and quantified5,6, which offers greater objectivity and specificity over clinical examination. However, its effectiveness hinges on gathering accurate analytical results in a timely manner. The requirement for specialist equipment, state-of-the-art testing facilities and trained personnel presents a severe bottleneck in current approaches to laboratory testing, which delays the diagnosis with potentially fatal outcomes7,8. Rapid and minimally invasive point-of-care (PoC) diagnostics (i.e., medical tests performed near or at the point of patient care), ideally self-manageable, could provide a solution for these problems.

PoC tests can relieve the strain many healthcare systems are facing with increasing healthcare demands combined with decreasing budgets and limited funding9, 10, 11. The most established and well-recognised PoC tests, albeit not for diagnosing infections, are undoubtedly the home pregnancy tests and personal glucose meters for diabetes monitoring. In the clinical setting, many other types of PoC tests are available from simple lateral flow testing strips to more complex microfluidic testing chips for use in portable handheld or benchtop devices12. These devices offer rapid testing for blood gasses, coagulation, endocrinology, cardiac markers and more, often on a single device with multiple single-use cartridges13. While PoC tests clearly have many advantages for delivering rapid diagnosis over traditional laboratory-based testing, many still require biological sample collection. Sampling procedures for blood, saliva, oral swabs, nasal swabs, tissue biopsies, urine, stool and genitourinary swabs can be considered invasive or intrusive because they make the patient uncomfortable. Blood sampling and tissue biopsies cause pain and physical trauma to the patient while also increasing the risk of infection as the skin barrier is broken14,15. The collection of swabs and bodily secretions may cause embarrassment and emotional trauma, leading to distress and anxiety. Moreover, sample collection by healthcare professionals also exposes key workers to the infection, a major risk that became evident throughout the recent COVID-19 and Ebola outbreaks16, 17, 18. For these reasons, alternative diagnostic mediums such as biofluids available in the skin, where sampling is minimally invasive and self-managed, are starting to be investigated.

The skin performs an important immunological function spanning both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. The skin-associated lymphoid tissue (SALT), comprising antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including macrophages and dermal dendritic cells, is found throughout the epidermis and dermis. In addition to performing a phagocytic function to remove infective agents, these APCs bridge the innate and adaptive immune systems by presenting antigens to T-helper cells, which in turn activate the humoral and cell-mediated immune responses19. A cutaneous infection will trigger a local immune response in the skin. Additionally, pathogenic antigens and host immune components relating to a systemic infection can also be detected in the skin. For example, Dengue, Zika and Ebola are non-cutaneous infections that have a cutaneous expression and can be diagnosed using biomarkers present in the skin (Table 1). Such biomarkers may include pathogenic antigens, nucleic acids (NAs) and components of the host immune response (e.g., host antibodies and cytokines) in the interstitial fluid (ISF) or capillary blood5,6. Therefore, the skin offers a unique window to monitor the body's infectious status. Detecting pathogenic markers is advantageous, as such markers are exogenous and therefore absent in non-infected individuals, so the tests are likely to be definitive. In terms of the host immune response, the innate response allows for early detection but is less specific, and therefore may be less definitive. On the other hand, the adaptive immune response is delayed and so tests based upon it typically detect infections at a later stage, but are likely to be more definitive due to the greater specificity. In any case, since infectious markers can be expressed and detected in the skin, the organ offers an attractive medium for minimally invasive and self-managed diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Table 1.

Infectious diseases with cutaneous expression and/or accessible biomarkers.

| Causative agent | Infection name | Infection type | Patient specimen | Current detection method(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Cat scratch disease (Bartonella henselae) | Cutaneous/localised | Blood draw | Cell culture, immunoassay & polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | 20 |

| Cellulitis | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy & blood draw | Cell culture, drug susceptibility testing & specific analyte monitoring | 2 | |

| Diphtheria | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy, nasal swab and throat swab | Cell culture & toxin detection by immunoassay & PCR | 21,22 | |

| Impetigo & Ecthyma | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab | Visual inspection, cell culture & drug susceptibility testing | 2 | |

| Leptospirosis | Cutaneous/localised | Skin biopsy, blood draw, urine sample & spinal fluid sample (rare) | Cell culture, microscopy, immunoassay & PCR | 2,23 | |

| Lyme disease & Erythema migrans | Cutaneous/localised & systemic/internal | Blood draw | Immunoassay | 2,24, 25, 26 | |

| Meningitis | Systemic/internal | Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) & blood draw | Cell culture, PCR & computerised tomography (CT) scans | 27 | |

| (Atypical) Mycobacteria spp. infections (other than leprosy & tuberculosis) | Cutaneous/localised | Skin biopsy & sputum sample | Cell culture, microscopy smear & PCR | 2,28 | |

| Mycobacterium leprae (Leprosy) | Cutaneous/localised | Skin biopsy | Visual inspection, cell culture, microscopy smear & PCR | 2,29,30 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) | Systemic/internal | Skin biopsy, blood draw & sputum sample | Cell culture, microscopy smear & PCR | 31,32 | |

| Sepsis | Systemic/internal | Blood draw | Cell culture, drug susceptibility testing & specific analyte monitoring. | 33, 34, 35 | |

| Staphylococcus spp. infections | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy | Cell culture & drug susceptibility testing. | 2 | |

| Streptococcal spp. infections | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy | Cell culture & drug susceptibility testing. | 2,36 | |

| Syphilis | Cutaneous/localised & systemic/internal | Skin swab & blood draw | Cell culture & Immunoassay | 37,38 | |

| Typhus | Systemic/internal | Skin biopsy & blood draw | Immunoassay | 39,40 | |

| Fungal | Candida spp. infections | Cutaneous/localised | Biopsy | Visual inspection & cell culture | 2 |

| Chromomycosis | Cutaneous/localised | Biopsy | Cell culture, microscopy & immunoassay | 41 | |

| Dermatophytosis | Cutaneous/localised | Biopsy | Cell culture, microscopy & immunoassay | 2,42 | |

| Lobomycosis | Cutaneous/localised | Biopsy | Cell culture, microscopy & immunoassay | 41 | |

| Mucormycosis | Cutaneous/localised | Biopsy | Cell culture & immunoassay | 43,44 | |

| Mycoses | Systemic/internal | Biopsy | Immunoassay | 2 | |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy | Cell culture, microscopy & immunoassay | 41 | |

| Sporotrichosis | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy | Cell culture, microscopy & immunoassay | 45 | |

| Plasmodium | Malaria | Systemic/internal | Blood draw | Blood smears, microscopy, immunoassay & PCR | 46 |

| Protozoa | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | Cutaneous/localised | Biopsy | Immunoassay & PCR | 47, 48, 49 |

| Viral | Dengue | Systemic/internal | Blood draw | Immunoassay & PCR | 50,51 |

| Ebola | Systemic/internal | Blood draw | Immunoassay & PCR | 50,52,53 | |

| Epstein–Barr virus | Cutaneous/localised & Systemic/internal | Blood draw | Immunoassay | 4 | |

| Herpes simplex virus | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy | Culture & immunoassay | 54,55 | |

| Human papillomavirus (HPV) | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab | Topical acetic acid application (during colposcopy) & PCR | 56,57 | |

| Varicella-herpes zoster (VZV) | Cutaneous/localised | Skin swab/biopsy & scab collection | Immunoassay | 2 | |

| Zika | Systemic/internal | Blood draw, urine & semen. | Immunoassay & PCR | 50,58,59 |

2. Microneedle diagnostic platforms

In recent years, transdermal microneedle technologies have emerged as a promising avenue for achieving accurate clinical diagnostics and health monitoring, with molecular-level specificity in near-real time. Traditionally developed to replace hypodermic needles for drug delivery applications60,61, microneedles can be described as miniature needles or micro-projections that are typically less than 1 mm in length and hundreds of micrometres wide. A microneedle array consists of a few to hundreds of such micro-projections and can be made, with or without a lumen, in a variety of shapes, i.e., conical, pyramidal, cylindrical or even fang-like to allow both efficient skin penetration and bioanalysis62, 63, 64. With regards to transdermal bioanalysis, microneedle devices for glucose monitoring have dominated the field from the early 2000s60, 65, 66, 67. By virtue of their dimensions, microneedle devices are painless as they avoid contact with nerve endings and blood vessels, with limited signs of skin irritation, and are well tolerated among patients14,15,68, 69, 70. Sampling from blood may require longer microneedles than sampling from the ISF, which increases the invasiveness of such devices. However, Gill et al.14 showed that microneedles up to 1.45 mm in length and 0.46 mm in width were significantly less painful than a 26-gauge (0.46 mm outer diameter) hypodermic needle inserted 5 mm into the skin. Silicon, metals, polymers, ceramic, glass and, more recently, nanocomposite materials have been employed towards the fabrication of microneedle devices using a range of techniques such as photolithography, drawing lithography, micromachining, 3D printing, micromoulding and thermal pulling (for glass)61,71, 72, 73, 74, 75.

Current microneedle-based diagnostic platforms broadly operate in one or more of the following ways: (1) biofluid extraction with in vitro analysis (Fig. 1A and B); (2) specific target analyte capture (Fig. 1C); and (3) in-situ electrochemical sensing (Fig. 1D)64,76. There are a limited number of microneedle diagnostic platforms that combine two or more of these mechanisms. These platforms offer different degrees of analyte specificity and rapidity (real-time/near real-time) towards bioanalysis (Fig. 2). Relatively few microneedle devices have been investigated specifically for infectious disease diagnosis. There are two clinical trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov relating to the use of microneedle devices for tuberculosis (TB) diagnosis, both using microneedles to administer tuberculin intradermally to observe delayed-type hypersensitivity skin reactions, similar to the Mantoux method77. One was completed in April 2013 but no results have been posted yet78, while the other was due to begin recruiting healthy volunteers in October 202079. In this instance, microneedles have been used as a minimally invasive alternative to the Mantoux method for diagnosing latent TB infections. The test is unique to TB and the dermal injection of an antigen to induce a visible skin reaction is limited in scope for adaptation to diagnose other diseases, so it will not be the focus of this article. A wealth of literature on microneedle-based diagnostic platforms for other, non-infectious diseases already exists. These platforms facilitate biomarker sampling or detection from/in the skin, and their design principles are generally adaptable to the detection and monitoring of various infectious diseases. These different modalities are discussed below and their use in infectious disease diagnosis, where applicable, is highlighted.

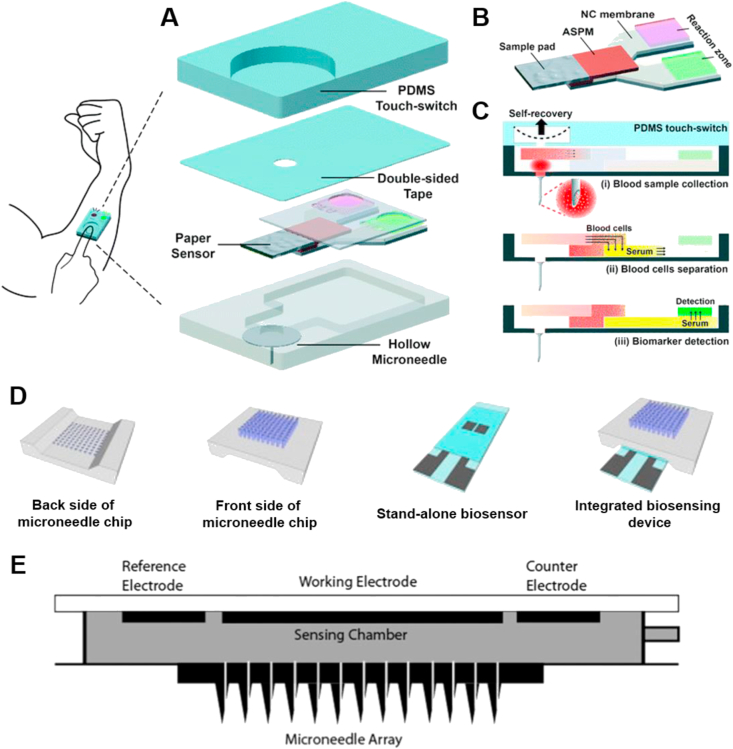

Figure 1.

Current microneedle diagnostic platforms function based on biofluid extraction using hollow (A) or solid (B) microneedles, specific target analyte capture (C) and electrochemical sensing (D). Adapted with permission from Ref. 64 and licenced under CC BY 4.0.

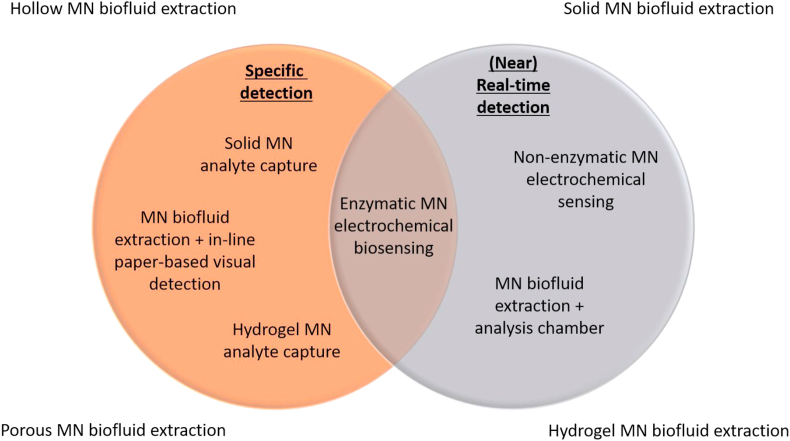

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing the desired infectious disease PoC diagnostic traits and the relationship between current microneedle (MN)-based platforms.

2.1. Biofluid extraction

The extraction of ISF and blood can be accomplished with hollow, hydrogel, porous and solid microneedles, although hollow microneedle-based extraction devices have seen the most development. Such devices act as a conduit to access dermal biofluids for on-chip analysis in microfluidic chambers60,65, 66, 67,80, 81, 82 (Fig. 3), or the collected biofluids can be transported out of the device for analysis using standard commercial assays61,83, 84, 85. Microneedle-based biofluid extraction devices are usually coupled with downstream analysis strategies to detect the presence of a particular analyte of interest. These strategies span a wide variety of techniques from conventional lab-based detection methods86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92 (including cell culture, microscopy, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and proteomic analysis) to alternative analyte sensing strategies. Here, we restrict our discussion to the biofluid extraction aspect of these devices, and discuss the detection backends in Sections 2.2, 2.3.

Figure 3.

Schematic images depicting various designs of microneedle arrays interfacing microfluidic on-chip analysis chambers. (A)‒(C) Schematic of a one-touch-activated blood multidiagnostic tool (OBMT). (A) OBMT complete device design and structure. (B) OBMT paper-based multiplex sensor. (C) Operating principle of the OBMT device. (D) Schematic of silicon dioxide transdermal biosensor showing the front side and backside of the microneedle chip, the ‘stand-alone’ sensor section and the full integrated device. (E) Schematic of a continuous glucose monitoring hollow silicon microneedle-based device with glucose sensing chamber. Permissions: (A)‒(C) Reprinted with permissions from Ref. 81 under copyright© 2015, The Royal Society of Chemistry; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (D) Adapted from Ref. 80 under copyright© 2015, Elsevier. (E) Reprinted from Ref. 82 under copyright© 2014, SAGE.

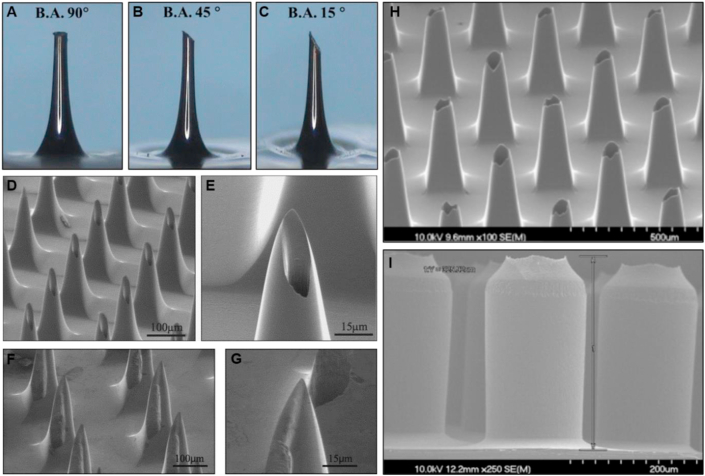

Efficient extraction of a sufficient volume of biofluid remains one of the greatest challenges for hollow microneedle-based diagnostic systems. Hollow microneedles with an inner diameter of 1–100 μm have been shown to facilitate efficient biofluid uptake71,93. However, reduced sampling rates and blockages can occur due the viscous nature of the biofluids and dislodging of biological material into the lumen from skin penetration, respectively83,94. To mitigate this effect, several design strategies have been illustrated such as, utilising a bevelled tip angle of 15°83,95, a tapered design of the microneedles themselves69,82, off-centre positioning of the lumen typically away from the tip of the microneedles69,96 and even a dual-lumen design97,98 (Fig. 4). Particularly for biofluid extraction over extended periods, it is important to ensure the microneedles remain securely in the skin throughout the sampling duration. To this end, a dual design consisting of hollow microneedles surrounded by solid microneedles has been used96. The solid microneedles stretched the skin over multiple contact points to provide anchorage and facilitate efficient skin penetration through friction adhesion. Application stability by the outer solid microneedles allowed efficient biofluid extraction through the inner hollow microneedles. Furthermore, multivariate algorithms have been developed that consider key parameters such as microneedle geometry, patch size and skin thickness, to provide a quality-by-design approach with defined critical quality attributes to achieve the desired device performance99. Rapid sampling of ISF is possible by increasing the number of microneedles in an array as shown by Strambini et al.80. A densely packed array consisting of 1 × 106 microneedles, measuring+ 100 μm in height and 4 μm in bore size, were able to fill a chamber at 1 μL/s. For continuous monitoring, it may be necessary to fine-tune the sampling rate to ensure device functionality over a prolonged time-period. For example, in a series of studies, Kobayashi and Suzuki developed an ‘intelligent mosquito’ system that utilised a volume phase-transition (poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)) (polyNIPAAm) gel system that shrank and expanded in response to a change in human body temperature100,101. They demonstrated that, by co-polymerising the gel with acrylic acid, ionized moieties can be introduced into the polymer backbone, which resulted in a continuous draw of blood for over 10 h at 4 μL/h. Jina et al.82 also demonstrated continuous monitoring for up to 72 h in ISF by passive diffusion of glucose through a hollow microneedle device. Hollow microneedle devices are typically coupled with on-chip electrochemical sensing for continuous monitoring as well as one-off detection. This detection strategy is discussed further in Section 2.2.

Figure 4.

Images of different design strategies for hollow microneedles. (A–C) Images of microneedles with bevelled tip angles of 90°, 45° and 15°. (D)‒(E) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images showing an array and single ‘hypodermic needle’ microneedle design where the orifice is shifted 25 μm off centre. (F)‒(G) SEM images showing an array and single ‘snake fang’ microneedle design where the orifice is shifted 50 μm off centre resulting in the opening on the side of the microneedle. (H)‒(I) SEM images of tapered and straight microneedle designs with the orifice at the tip. Permissions: (A)‒(C) Reprinted from Ref. 83 under copyright© 2013, Springer Nature. (D)‒(G) Reprinted from Ref. 96 under copyright© 2004, Elsevier. (H)‒(I) Reprinted from Ref. 69 under copyright© 2013, Elsevier.

In addition to hollow devices, solid microneedle arrays have also been used to access subcutaneous biofluids by creating micropores in the skin. It has been demonstrated that multiple insertions of a solid microneedle device encourage the biofluids to migrate to the skin surface through the micropores, allowing them to be absorbed into strips of paper attached to the device (Fig. 5A‒C)102,103 or collected via vacuum suction72,84. More recently, new microneedle designs have emerged for ISF extraction in the form of porous and hydrogel microneedles. Porous microneedles can be considered a hybrid between solid and hollow microneedles. They are fabricated in a way that allows large interconnected pores to form in the body of the microneedle while still maintaining structural strength (Fig. 5D‒E). Subsequently, ISF can be extracted from the skin by simple capillary force and collected from the microneedles using centrifugation73,104. Hydrogel microneedles, on the other hand, act like a sponge and swell upon insertion into the dermal interstitium, absorbing ISF using a diffusion gradient (Fig. 5F). Like porous microneedles, the extracted ISF can be liberated from the hydrogel microneedles by centrifugation and analysed using established analytical methods such as HPLC87,88,105, 106, 107, 108, 109.

Figure 5.

Images of solid, porous and hydrogel microneedle designs. (A)‒(C) Biofluid extraction device comprising of a row of 9 solid microneedles in series with absorbent paper attached. (D)‒(E) Optical micrograph and SEM image of a single porous microneedle fabricated from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). (F) Gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel microneedle array showing appearance change after different durations of fluid uptake. Permissions: (A)‒(C) Reprinted from Ref. 102 under copyright© 2019, John Wiley & Sons. (D)‒(E) Reprinted from Ref. 110 under copyright© 2019, Springer Nature. (F) Reprinted from Ref. 111 under copyright© 2020, John Wiley & Sons.

2.2. Sensing systems

Infectious disease detection using biosensing devices is an emerging approach towards health and infection transmission monitoring. These devices typically comprise a signal transducer (an electrode) modified with a recognition element (an enzyme or antibody) that confers specific interactions with the target analyte of interest, relaying a quantifiable electrical signal that correlates with the relative abundance of the target112. Detection of pathogenic infections using biosensors can either be direct (where the whole pathogen is detected by the sensor) or indirect (biosensor detects secreted metabolites or nucleic acids from the invading organism). Signal quantifying techniques include amperometry, voltammetry (cyclic (CV), differential pulse (DPV), square wave (SWV)) and impedance spectrometry113,114. Direct current (DC) voltammetric or amperometric sensors measure changes in current due to target interactions, whereas impedance-based biosensors use alternating currents (AC) to detect changes in resistance at the electrode surface113,114. These changes are triggered by a target-specific molecular recognition event (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Modes of electrochemical sensing for the detection of bacteria. (A)‒(B) Examples of indirect bacterial detection using direct current (DC)-based techniques. Square wave voltammetry (SWV) plots current vs. potential and chronoamperometry plots current vs. time. (A) Sensing of cell-secreted metabolites via redox reactions. (B) Sensing of exogenous bacterial enzymatic electroactive by-products. (C)‒(D) Examples of direct bacterial detection using impedimetric or alternating current (AC)-based techniques. (C) Bacterial binding event causes a change in impedance due to reduced electron transfer activity of a mediator as a result of surface passivation. Signal is typically represented on a Nyquist plot. (D) Bacterial binding event is measured by a change in capacitance as a function of AC frequency. Reprinted from Ref. 113 under copyright© 2020, American Chemical Society.

There is a wealth of literature detailing biosensing platforms for the detection of infectious agents113,115, 116, 117, 118. A recent minireview highlighted the latest advances in rapid biosensing of common opportunistic bacterial pathogens (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus & Escherichia coli) in clinical settings117. The development of Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV) and Human enterovirus 71 (hand, foot and mouth disease) biosensors has also been reported using electrochemical sensing techniques115,119. However, integration of biosensing technologies into microneedle-based platforms for use in infectious disease diagnostics has been underexplored. Historically, microneedle sensing systems have been heavily developed for blood glucose monitoring, so that is where most of the technological advances have been made. For this reason, some of the following discussions will necessarily be had against this backdrop. However, we will outline the general design principles and mechanisms of these microneedle devices with a view to translating them to infectious disease diagnostic applications in the future.

Both hollow and solid microneedles can be incorporated into an electrochemical sensing platform for real-time or near-real time detected of target analytes in the skin. We have discussed hollow microneedles for biofluid extraction in Section 2.1. Though microneedle-mediated biofluid extraction is beneficial due to its minimally invasive nature, combining this with a sensing strategy is important to address diagnostic opportunities. For accurate functioning, aside from microneedle design optimisations, the integrated sensor needs to incorporate multiple elements such as a reservoir patterned with appropriate assay formulations alongside working and counter electrodes, inlet and outlet channels, flow through channels incorporating dialysis membranes to prevent large high molecular weight proteins from adsorbing and fouling the sensor (particularly in relation to blood sampling), and a pumping mechanism for both sample retrieval and removal. Systems integration and miniaturisation is therefore a major challenge, whilst the inherent complexity in design can significantly impact reliability and reproducibility when manufacturing such devices. Nonetheless, clinical studies on hollow microfluidic devices indicate that acceptable performance to a clinical standard can be deduced from such devices67,120.

Another approach is in-situ sensing, where the microneedles act as electrodes that detect the analytes within the skin in real time. There are two design strategies for fabricating in-situ microneedle sensors. The first involves the development of electroactive solid microneedles, while the second uses hollow microneedles to house conventional electrochemical sensing elements, such as modified carbon pastes and fibres121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128. The fabrication of solid microneedle sensors typically employs sputtering or e-beam evaporation to metallise polymeric or metallic microneedles to produce an electroactive surface, which is then functionalised with an appropriate enzyme or coating to selectively detect an analyte62. Metallisation typically uses expensive metals such as gold or platinum to create a highly conductive electroactive surface area. Hence, polymeric nanocomposite solid microneedles based on inexpensive nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes provide an attractive alternative122. In comparison to hollow microneedles housing a modified electrode, optimal utilisation of such nanocomposites can significantly improve the mechanical strength of the microneedles whilst also increasing the electroactive surface area due to the high aspect ratio of the nanomaterial121, 122, 123. Nonetheless, the electroactive materials used to fabricate both solid and hollow in-situ sensors are already well established in the field of electroanalysis62. Carbon nanotube and carbon paste electrodes, in particular, offer the very desirable combination of low background current, easy customisation, low cost and ease of fabrication. Moreover, in-situ biosensors offer a simpler design than microfluidic biosensors and are particularly advantageous towards multi-analyte detection, since each microneedle/transducer can be selectively modified with a different recognition element. In contrast, for microfluidic biofluid extraction devices, multi-analyte detection poses a significant challenge, as all the different recognition elements and transducers will need to be integrated within the confined space of a single microfluidic compartment.

Both solid and hollow microneedle-based in-situ sensors have detected therapeutic drugs, electrolytes, alcohol, pH changes, small molecules, including glucose, nitric oxide, ascorbic acid, uric acid, dopamine, glutamate, neurotransmitters and organophosphorus nerve agents61,62,66,93,122,124, 125, 126,128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141. For solid microneedle biosensors, recognition elements such as enzymes are typically cross-linked to the microneedle surface using covalent cross-liking chemistries to protect them from accidental removal or degradation during skin application142. For example, Hwa et al.143 developed a glucose sensor on a gold electrode by assembling glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme using the activated carboxy terminus (EDC/NHS chemistry) of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) with 3-mercaptopropionic acid. SAMs are known for being easy to deposit on metallic surfaces to allow molecular linkage. This sensor showed enhanced stability whereby 80% of the enzyme was retained over 7 days. To improve shelf-life, the authors suggested adding a hydrogel layer over the enzyme layer, or depositing GOx using layer-by-layer assembly with a suitable polymer. More commonly, recognition elements are typically deposited onto solid microneedle electrodes using electropolymerisation of poly(o-phenylenediamine) (PPD)130,141, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT)144,145 and polyphenol (PP)139, or drop casted using Nafion solutions to create a polymer film124,130. These strategies are used to entrap enzymes within the polymer films, thus confining the recognition element to the microneedle. Overall, this results in enhanced an enzyme stability and signal-to-noise ratio. The choice of polymer film needs careful consideration, as they can help prevent common interferants such as ascorbic acid, uric acid, dopamine and acetaminophen from fouling the electrode. Sharma et al.137, however, reported that their device with a PP film required application for an hour to allow the sensor to equilibrate with ISF and achieve a stable baseline before readings could be taken. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has also been used in conjunction with solid metal-coated microneedles for the in-situ detection of glucose, pH and the hemozoin, a metabolite of haemoglobin produced by malaria parasites in infected erythrocytes137,146, 147, 148. The mechanism of SERS is apparently related to the frequency of monochromatic light changes on a surface based on the interactions with a molecule where the resulting signal is subsequently enhanced using metal nanoparticles149. For in-situ glucose measurements, the capture probe 1-decanethiol (1-DT) was immobilised onto Ag-coated solid microneedle arrays then applied to the dorsal skin of mice. A Raman microspectroscopy system was used to facilitate subsequent SERS signal detection through the microneedle array147.

In comparison to solid electroactive microneedles, hollow microneedles can offer an added degree of protection as they effectively conceal the electrode and therefore the recognition element within bores of individual microneedles. For example, Windmiller et al.141, adopted an approach of concealing solid metallised microneedles with a hollow microneedle to selectively detect glucose; Mohan et al.130 used modified platinum wires to detect and continuously monitor alcohol over a period of 100 min; and similarly, Miller et al.136, used modified carbon fibre electrodes to detect hydrogen peroxide and ascorbic acid. This approach allows the mechanical and electrochemical properties of the microneedles to be considered separately during device development, therefore opening up more options in terms of material choice.

Whilst these studies did not examine infectious diseases specifically, they provide the technical basis for similar devices to be developed for infectious disease diagnosis, since the ability to manipulate the mechanical and electrochemical properties of electrochemical sensing microneedles, as well as coupling to a suitable detection backend, is important for any application, including infectious disease diagnosis. Some of these technologies may also be relevant in other ways. For instance, glucose oxidase, commonly found in microneedle-based glucose sensors, has separately been incorporated into ‘enzyme-channelling’ immunosensors for infectious disease diagnosis150. In this setup, glucose oxidase and target specific capture antibodies were immobilised on the electrode in a sandwich ELISA format. In the presence of glucose, it produces the H2O2 needed by the peroxidase within the captured immunocomplex to generate a signal on the electrode surface.

The performance of enzyme-based biosensors is limited by several factors. Although some enzymes are considered stable, they may lose activity when exposed to heat or other chemicals. An enzyme’ s active centre is covered by a protein shell, making electron transfer between the enzyme and the electrode a difficult process that often requires the aid of electron transfer mediators such as organic dyes, ferrocene and metal complexes121,151. Some studies have attempted to alleviate these issues by designing non-enzymatic microneedle sensing arrays. These have been fabricated from metallic and polymeric nanocomposites with anti-fouling films to increase the sensing surface area and signal output from the electrochemical redox reaction121, 122, 123,131,140,152. Similarly, this is an important consideration for microneedle-based immunosensing in the context of infectious disease diagnosis, since most immunosensing technologies utilise enzymatic redox reactions, usually based on peroxidase.

Another alternative to recognition element-based sensors is ion-selective sensors which can monitor pH changes and electrolyte concentrations in the skin93,128,129,135. Miller et al.128 reported multiplexed detection of pH fluctuations, lactate and glucose using hollow microneedle electrodes filled with a modified carbon paste. RR diazonium salt was chemically deposited onto the pH specific electrode for pH monitoring by cyclic voltammetry. Reports have shown a relationship between fluctuations in normal skin pH and bacterial infections153, however, these pH changes can also be induced by exercise and diet129, therefore diminishing the specificity of these sensors.

2.3. Analyte capture microneedles

Microneedle systems in this category incorporate recognition elements or probes that confer analyte specificity. In this instance, the recognition elements are usually antibodies, oligonucleotides or other proteins capable of binding to specific molecular motifs. It can effectively isolate the target analyte from a complex biological matrix, thus allowing the proverbial needle to be picked from the haystack.

One embodiment of this technology is immunocapture microneedles, whereby capture antibodies are immobilised on to the surface of solid microneedles or embedded into hydrogel microneedles. Using this technique, microbial antigens, host antibodies and other cytokines have been captured from the skin at concentrations comparable to the assay limits of conventional immunoassays85,118,154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, and in some cases in under 1 min161. Post-capture antigen confirmation and quantification can be accomplished using conventional techniques, such as ELISA followed by spectrophotometry, or via a simple paper-based visual analysis followed by densitometry155. Sampling in this way eliminates the sample preparation step that most other pathological tests require before analysis can be performed.

Microneedle geometry, surface area, probe density and probe orientation can influence signal uniformity and signal output162,163. These parameters should be optimised to maximise the availability of target binding sites. Increasing the microneedle surface area from 20,000 to 30,000 projections/cm2 demonstrated a linear correlation with increased biomarker capture and a 1.2-fold signal-to-noise improvement compared to the control array. The high-density device detected anti-FluVax-IgG within 30 s of application with 100% diagnostic sensitivity. Notably, increasing the number of microneedles per array did not have an adverse effect on mechanical strength, penetration mechanism or patient pain perception161,164.

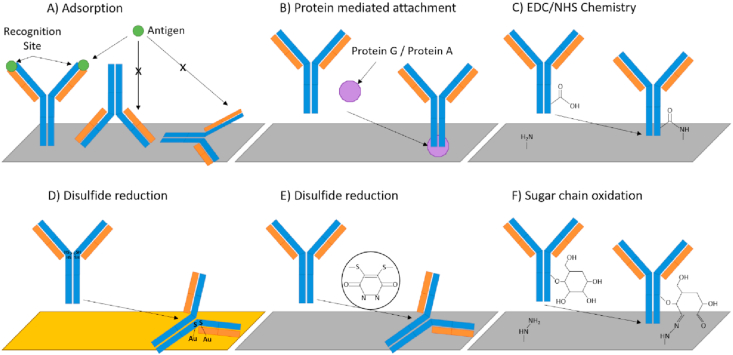

Antibody adsorption is the simplest immobilisation technique but other crosslinking strategies have been used to deposit antibodies onto a desired surface (Fig. 7). Often, antibody adsorption results in a ‘flat-on’ antibody orientation where the Fc region lies flat on the deposition surface and limits antigen access (Fig. 7A). Steric hindrance of antigen recognition sites due to poor antibody immobilisation orientation has been demonstrated to result in a loss in bioactivity and reduced immunoassay sensitivity162,165, 166, 167. Incorporation of certain proteins during surface modification can encourage affinity-based anchorage of multiple antibodies in a favourable orientation (Fig. 7B). Protein G, for example, is a streptococcal bacterial protein with multiple binding sites specific to the Fc regions of antibodies. Utilising this protein during capture probe deposition onto microneedle arrays improved antibody orientation and increased the in vivo capture efficiency of dengue virus NS1 marker in murine models158. Alternatives to whole antibody capture probes have started to emerge for use in benchtop ELISAs in the form of fragmented antibodies and aptamers. These smaller recognition elements provide a robust, stable structure with potentially increased probe density, antigen affinity and reduced non-specific binding113,168, 169, 170, 171. While investigating the stability of their surface chemistry in vivo, Bhargav et al.162 found that ∼20% of the attached capture probe was released into the skin during application. Therefore, the biocompatibility and chemical stability of the surface modifications must be carefully considered to avoid an unwanted, artificial immune response during microneedle application, which could potentially mask, amplify or negate the true diagnosis.

Figure 7.

Known antibody immobilisation strategies for immunosensors. (A) Uncontrolled antibody adsorption. (B) Protein mediated antibody orientation and immobilisation. (C) 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminoproply) carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDC/NHS) coupling creating robust covalent linkage via amine bond formation. (D) Reduction of antibody disulfides to create thiol groups for immobilisation onto gold surfaces. (E) Reduction of antibody disulfides for site specific coupling. (F) Oxidation of sugar chains to create reactive aldehyde groups. Image adapted with permission from Ref. 165 and licenced under CC BY 4.0.

By immobilising different capture antibodies on to different microneedles and administering them at the same time multiple analytes can be detected simultaneously155,157,159. Multiplexed microneedle arrays incorporating separate capture antibodies for the Plasmodium falciparum Histidine-Rich Protein 2 (PfHRP2), the dengue virus protein NS1 and total IgG detected PfHRP2 and IgG in mice inoculated with PfHRP2 protein. Antigen detection was performed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-tagged modified ELISA technique in a microplate and analysed with UV spectrophotometry157. Although the dengue protein NS1 was used as a negative control in this study, it demonstrated the principle of multiplexing on immunocapture microneedles. Likewise, four regions on a single microneedle array were individually coated with capture antibodies for mouse IL-6 and IL-1α (primary targets) as well as positive (detection antibody only) and negative control (human TNFα) antibodies. For colorimetric detection, the array was applied to a paper soaked with OPD (o-phenylenediamine) substrate, which develops a yellow signal in the presence of HRP (Fig. 8). Densitometric quantification revealed an intense signal even at very low levels (≤50 pg/mL); thereby implying high sensitivity155 (Fig. 9). Multiplexing capability is important for two key scenarios; (1) to aid differential diagnosis and (2) to have in-device controls for key parameters such as successful penetration and to confirm specific antibody–antigen interactions. These multiplexed microneedle systems have the potential to be scaled up and modified for the detection of other pathogens and even incorporated into panel detection systems to rule in/out specific infections based on similarly presenting symptoms as seen with skin infections.

Figure 8.

Paper-based detection of human TNF-alpha using analyte-capturing microneedles. Colour signals generated through the enzymatic reaction between OPD and HRP can be blotted on to paper, which concentrates the signal and offers information about the spatial distribution of the target biomarker. Reprinted from Ref. 155 under copyright© 2015, Controlled Release Society.

Figure 9.

Densitometric analysis used in conjunction with paper-based detection of cytokines from the skin, showing (A) multiplexing capabilities (IL-1alpha, IL-6 and assay controls) and signal visualisation, (B) signal quantification by densitometry, and (C) validation using standard plate-based ELISA. Reprinted from Ref. 155 under copyright© 2015, Controlled Release Society.

As well as antigens, antibodies and cytokines, the detection of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (NAs) in ISF and capillary blood can also be indicative of disease or infection. The diagnostic potential of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has been reported for a number of conditions, including a wide range of cancers, however, detection strategies are often PCR-centric and specific to blood and urine specimens31,172, 173, 174. These circulating cell-free nucleic acids have been found in ISF and other biofluids in similar concentrations to blood and urine making transdermal access via microneedle arrays a possibility for rapid PoC diagnosis175.

Hydrogel microneedles have been modified with sequence specific hybridisation probes to absorb and capture cutaneous circulating cell-free nucleic acids. Capture of microRNA in ISF has been demonstrated by hybridisation to an alginate-PNA (peptide nucleic acid) capture probe covalently bound to the surface of a polymer microneedle array coated with hydrogel layers. The captured microRNA was then incubated with fluorescently tagged oligonucleotide probes and quantified using fluorescent confocal microscopy176. This technique is advantageous as it did not require nucleic acid amplification. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) cfDNA has been captured using a similar technique. EBV cfDNA was captured on complimentary single stranded oligonucleotide probes in a hydrogel microneedle surface and quantified using traditional NA amplification. DNA capture efficiency (as determined by PCR) was found to drop considerably when the DNA concentration in simulated ISF was in low abundance. In vivo skin testing concluded that the detection limit of this device was 370,000 copies/mL, however, disease causing concentrations of EBV cfDNA have been reported as low as 134 copies/mL therefore indicating that the sensitivity of this device needs improving177.

To address the issues surrounding device sensitivity and capture efficiency, the same group incorporated a DNA enrichment technique into the hydrogel microneedle capture platform. Iontophoresis (IP) is a technique whereby molecules can be manipulated to migrate through a medium towards an electrode - in this instance, reverse IP was used to attract negatively charged DNA fragments in skin towards microneedles attached to an anode. The hydrogel microneedles then absorb the DNA fragments which are then captured on sequence specific capture probes bound to the surface of the microneedles, eluted in buffer and quantified using PCR. Maximum capture efficiency with the reverse IP technique was reported at 95.4% with a detection limit of 5 copies/μL. This technique outperformed hydrogel microneedle capture without the reverse IP functionality and blood sampling with commercial DNA extraction. More importantly, the device successfully detected EBV cfDNA from immunodeficient mice with early stage and advanced tumour development178.

2.4. Crossover technologies

Fig. 2 illustrates different microneedle technologies and how they compare in terms of specificity and speed of detection—the two key requirements that are critical for the efficacy of a PoC diagnostic device. The ideal PoC technology will be situated in the overlapping region between the two circles in the Venn diagram. There have been a limited number of studies examining microneedle diagnostic platforms that incorporate two or more of the preceding mechanisms (Sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3). An example of this is electrochemical biosensors that incorporate recognition elements to achieve both rapid detection and target specificity.

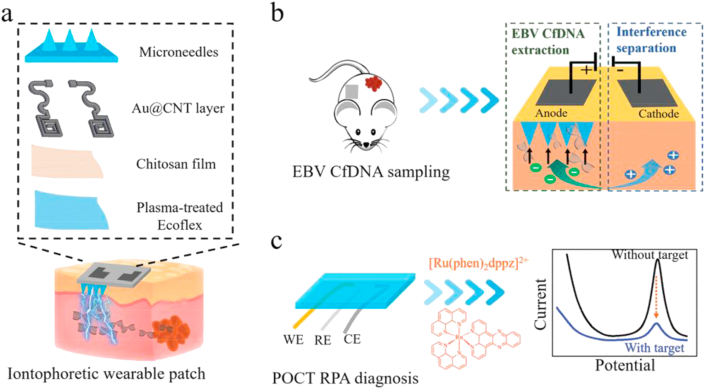

Song et al.179 developed a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) biosensor for the specific, real-time detection of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor—a cancer biomarker). The analyte capture component comprised a solid AuSiO2 microneedle array functionalised with peptide aptamers. The device demonstrated that VEGF binding events corresponded to a measurable change in capacitance between microneedles within 5 min using a two-step capacitance-to-digital converter to visualise the response. For device functionality, the microneedle array was attached to a printed circuit board (PCB), logic analyser, laptop and power supply. In vitro experiments with human blood showed no interference from other blood constituents and detected VEGF within the concentration range of 0.1–1000 pmol/L179. Other similar impedance-based detection using immobilised recognition elements have been reported for Ebola virus and CD4 cell quantification for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) diagnosis85,118. In these devices, biofluids were transported through microfluidic channels into sensing chambers for electrochemical target detection. Alternatively, Yang et al.178 developed a near-real-time microneedle platform capable of isolating specific viral circulating free DNA from the skin by complementary probe hybridisation. On-chip isothermal amplification and the addition of an intercalating electrochemical probe (methylene blue) facilitated signal detection and quantification by DPV. The sophisticated device incorporated a hydrogel matrix for ISF entrapment, an iontophoretic component for target enrichment and an electrochemical sensor (Fig. 10). However, the authors did not indicate the total time taken to complete the analysis. Nonetheless, these crossover technologies are exciting developments because they highlight the possibility of integrating complementary diagnostic principles into a complete microneedle-based diagnostic platform.

Figure 10.

Schematic depiction of an iontophoretic wearable and microfluidic electrochemical sensor based on microneedles: (A) construction of the microneedle device; (B) extraction of EBV cfDNA from the ISF in mice by reverse iontophoresis and entrapment in the hydrogel microneedles; (C) electrochemical quantification of the captured cfDNA using a 3-electrode system (WE: working electrode; RE: reference electrode; CE: counter electrode). Reprinted from Ref. 178 under copyright © 2020, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

3. Challenges and future outlook

The general approach to infectious disease diagnosis is the detection of biomarkers originating from either the invading pathogen or the host immune response. Effective PoC diagnostics should fulfil the ‘ASSURED’ (affordable, sensitive, specific, user-friendly, rapid and robust, equipment-free and deliverable to end-users) criteria180 established by the World Health Organization (WHO). Access to a stable power supply, stable reagents, a sterile test environment, appropriate packaging and disposal procedures are considerations that need special attention, especially for low-resource settings. Decentralised, rapid, PoC diagnosis of disease is essential for improving healthcare globally. Microneedle PoC systems are advantageous as they can be utilised to extract quantitative information rapidly for frequent monitoring and diagnostic purposes. Moreover, transdermal diagnostics via microneedle-based devices offer the potential to move laboratory scale instruments into miniaturised platforms that can be utilised by minimally trained individuals, including potential self-administration by the public60,181,182. Thus, it can radically transform clinical practice into a more efficient, economically viable and highly accessible format.

There are some outstanding challenges with such devices relating to design considerations such as material choice, microneedle shape, bore size (for hollow microneedles), and manufacturability. In particular, on-chip detection facilitates rapid PoC diagnostics but inevitably requires sophisticated, multi-component assemblies which may compromise manufacturability, increase resource requirements and present significant challenges in terms of miniaturisation. There is also the question of how well blood or ISF levels of given biomarkers reflect infection status. It is known that there is often a concentration difference between ISF and blood for certain biomarkers that are dependent on time and molecular size89,92,183. These challenges can be mitigated so long as such discrepancies are well characterised and a correlation is established. Another factor to consider is the relative abundance of biomarkers at different skin depths and localisation to specific regions of the skin5,155,156,184. In principle, it is possible to address the depth profile of biomarkers by varying the microneedle length, but empirical data on this has been scarce. For low-abundance biomarkers in the ISF, detection efficiency may be improved using external influences to achieve target enrichment, e.g., iontophoresis to attract the analyte towards the recognition elements of biosensors178, capillary extravasation using a low-density targeted laser185 and, indeed, by application of the microneedle array itself186. Many of the technologies featured above already leverage nanotechnology to improve performance. Ongoing advancements in nanotechnologies such as nanowires, nanocomposites and nanoencapsulation should further facilitate the miniaturisation of microneedle-based diagnostic platforms into wearable devices187. In order to reduce the resource requirements for microneedle-based PoC devices, innovative designs that do not require a power source, such as a paper-based visual detection system155 or manual centrifugation using a fidget spinner188,189, can be considered. Alternative power sources have been devised which may be incorporated into microneedle platforms80,190,191. For example, a biofuel cell that derives biochemical energy from the ISF could remove the need for an external power source126.

The microneedle technologies discussed in this review are mostly suited for PoC approaches and can be highly useful in complex biological samples including those with polymicrobial populations. Each microneedle technology, when used alone, has its own strengths and limitations, but when used in combination, they can offer powerful diagnostic tools for infectious diseases. For example, electrochemical sensors can rapidly (real-time or near real-time) detect electroactive small molecules, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) which may be suitable for detecting the oxidative burst associated with the antimicrobial action of neutrophils—a well-established marker of microbial infection113,192,193. However, on its own, ROS detection will not identify the infectious agent nor confirm microbial infection as the source of the ROS. In comparison, immunocapture microneedles are more versatile as they can potentially detect both the pathogenic antigen and specific host immune antibodies associated with the infection, but analysis takes longer.

Microneedle platforms could also be adapted for broader diagnostic applications beyond the skin, including where internal examinations would conventionally be necessary. For example, Keum et al.145 attached a microneedle array to an endomicroscope for the dual functionality of internal imaging of polyps and sensing of nitric oxide within the colon. Continuous monitoring multiplexed microneedle platforms could also incorporate therapeutic drug activity alongside infectious agent detection to observe treatment progression. Microneedle sensors have already been documented for their successful monitoring of levodopa132 and β-lactam antibiotics133,194 which can pave the way for more personalised medicine and prevent the overuse and misuse of antibiotics.

4. Conclusions

Many infections, even if they are not primarily dermal infections, can be detected in the skin. In this regard, transdermal microneedle devices can potentially offer rapid, self-manageable and biomarker-based PoC diagnostics for infectious diseases. Various microneedle-based diagnostic platforms have been developed to either sample biomarkers from the skin or detect them in-situ. These include microneedles that extract blood or ISF, microneedle sensing systems, analyte capture microneedles and combinations thereof. Although not many of these have been specifically demonstrated for infectious disease detection, microneedle-based infectious disease diagnostics can generally benefit from the technical know-how accumulated through development work that has focused on other diseases, since the technical challenges are similar. The prospect of integrated lab-on-a-chip microneedle devices is a particularly exciting one because it could overcome the bottleneck and accessibility issues of centralised test facilities to greatly accelerate the diagnosis. This is particularly pertinent in the context of infectious diseases where the current needs for personnel travel, sample transportation and extensive sample processing could increase the risk of disease transmission. With further development, microneedle-based platforms have the potential to realise true PoC diagnostics for infectious diseases, replacing the current laborious testing regimes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, UK.

Author contributions

Rachael V. Dixon, Eldhose Skaria and Keng Wooi Ng wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine . In: Improving diagnosis in health care. Balogh E.P., Miller B.T., Ball J.R., editors. National Academies Press (US); Washington, D.C.: 2015. The national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine the diagnostic process. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miró E.M., Sánchez N.P. In: Atlas of dermatology in internal medicine. Sánchez N.P., editor. Springer; New York, NY: 2012. Cutaneous manifestations of infectious diseases; pp. 77–119. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leptospirosis Information Centre Leptospirosis information - other infections with similar symptoms. Leptospirosis org. http://www.leptospirosis.org/other-infections-with-similar-symptoms/ Available from:

- 4.Centers for disease control and prevention Epstein-Barr virus and infectious mononucleosis. https://www.cdc.gov/epstein-barr/about-ebv.html Available from:

- 5.Paliwal S., Hwang B.H., Tsai K.Y., Mitragotri S. Diagnostic opportunities based on skin biomarkers. Eur J Pharmaceut Sci. 2013;50:546–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayeux R. Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations. J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2004;1:182–188. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Car L.T., Papachristou N., Bull A., Majeed A., Gallagher J., El-Khatib M. Clinician-identified problems and solutions for delayed diagnosis in primary care: a prioritize study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:131. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0530-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okten I.N., Aktas Sezen B., Gunaydin U.M., Koca S., Ozturk T., Ozder H.T. Factors associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36 e22141–e22141. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konwar A.N., Borse V. Current status of point-of-care diagnostic devices in the Indian healthcare system with an update on COVID-19 pandemic. Sens Int. 2020;1:100015. doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St John A., Price C.P. Existing and emerging technologies for point-of-care testing. Clin Biochem Rev. 2014;35:155–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manocha A., Bhargava S. Emerging challenges in point-of-care testing. Curr Med Res Pract. 2019;9:227–230. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J., Wang K., Xu H., Yan W., Jin Q., Cui D. Detection platforms for point-of-care testing based on colorimetric, luminescent and magnetic assays: a review. Talanta. 2019;202:96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.i-STAT Test Cartridges Abbott point of care. https://www.pointofcare.abbott/int/en/offerings/istat/istat-test-cartridges Available from:

- 14.Gill H.S., Denson D.D., Burris B.A., Prausnitz M.R. Effect of microneedle design on pain in human volunteers. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:585–594. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816778f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haq M.I., Smith E., John D.N., Kalavala M., Edwards C., Anstey A. Clinical administration of microneedles: skin puncture, pain and sensation. Biomed Microdevices. 2009;11:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10544-008-9208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.-G., Ma W. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raven J., Wurie H., Witter S. Health workers' experiences of coping with the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone's health system: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:251. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3072-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sylvester Squire J., Hann K., Denisiuk O., Kamara M., Tamang D., Zachariah R. The Ebola outbreak and staffing in public health facilities in rural Sierra Leone: who is left to do the job? Public Health Action. 2017;7:S47–S54. doi: 10.5588/pha.16.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabashima K., Honda T., Ginhoux F., Egawa G. The immunological anatomy of the skin. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:19–30. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC bartonella infection (cat scratch disease, trench fever and carrion's disease) https://www.cdc.gov/bartonella/clinicians/index.html Available from:

- 21.Engler K.H., Efstratiou A., Norn D., Kozlov R.S., Selga I., Glushkevich T.G. Immunochromatographic strip test for rapid detection of diphtheria toxin: description and multicenter evaluation in areas of low and high prevalence of diphtheria. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:80–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.80-83.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberto C., Osdoit S., Villani A.P., Bellec L., Belmonte O., Schrenzel J. Cutaneous ulcers revealing diphtheria: a re-emerging disease imported from Indian Ocean countries? Ann Dermatol Vénéréol. 2021;148:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budihal S.V., Perwez K. Leptospirosis Diagnosis: competancy of various laboratory tests. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:199–202. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6593.3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz I., Wormser G.P., Schwartz J.J., Cooper D., Weissensee P., Gazumyan A. Diagnosis of early Lyme disease by polymerase chain reaction amplification and culture of skin biopsies from erythema migrans lesions. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3082–3088. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3082-3088.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badawi A. The potential of omics technologies in lyme disease biomarker discovery and early detection. Infect Dis Ther. 2017;6:85–102. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0138-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salazar J.C., Pope C.D., Sellati T.J., Feder H.M., Kiely T.G., Dardick K.R. Coevolution of markers of innate and adaptive immunity in skin and peripheral blood of patients with Erythema migrans. J Immunol. 2003;171:2660–2670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman O., Weber R.J. Pathophysiology and treatment of bacterial meningitis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1756285609337975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien D.P., Globan M., Fyfe J.M., Lavender C.J., Murrie A., Flanagan D. Diagnosis of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease: Be alert to the possibility of negative initial PCR results. Med J Aust. 2019;210 doi: 10.5694/mja2.50046. 416–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Diagnosis of leprosy. http://www.who.int/lep/diagnosis/en/ Available from:

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hansen's disease (leprosy) https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/health-care-workers/laboratory-diagnostics.html Available from:

- 31.Fernández-Carballo B.L., Broger T., Wyss R., Banaei N., Denkinger C.M. Toward the development of a circulating free DNA-based in vitro diagnostic test for infectious diseases: a review of evidence for tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01234-18. e01234-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Latent TB infection and TB disease. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/tbinfectiondisease.htm Available from:

- 33.Fan S.L., Miller N.S., Lee J., Remick D.G. Diagnosing sepsis—the role of laboratory medicine. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;460:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer M. Biomarkers for sepsis—past, present and future. Qatar Med J. 2019;2019 doi: 10.5339/qmj.2019.qccc.8. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierrakos C., Velissaris D., Bisdorff M., Marshall J.C., Vincent J.-L. Biomarkers of sepsis: time for a reappraisal. Crit Care. 2020;24:287. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bisno A.L., Stevens D.L. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:240–246. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Health Service, UK Testing—syphilis. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/syphilis/diagnosis/ Available from:

- 38.Carlson J.A., Dabiri G., Cribier B., Sell S. The Immunopathobiology of syphilis: the manifestations and course of syphilis are determined by the level of delayed-type hypersensitivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:433–460. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181e8b587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ching W.-M., Rowland D., Zhang Z., Bourgeois A.L., Kelly D., Dasch G.A. Early diagnosis of scrub typhus with a rapid flow assay using recombinant major outer membrane protein antigen (r56) of orientia tsutsugamushi. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:409–414. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.2.409-414.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saraswati K., Day N.P.J., Mukaka M., Blacksell S.D. Scrub typhus point-of-care testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miranda M.F.R., Silva A.J.G. Vinyl adhesive tape also effective for direct microscopy diagnosis of chromomycosis, lobomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;52:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasch J. Diagnosis of dermatophytosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2014;8:198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gartenberg G., Bottone E.J., Keusch G.T., Weitzman I. Hospital-acquired mucormycosis (Rhizopus rhizopodiformis) of skin and subcutaneous tissue. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:1115–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197811162992007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diagnosis and testing of mucormycosis. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mucormycosis/diagnosis.html Available from:

- 45.Bonifaz A., Toriello C., Araiza J., Ramírez-Soto M.C., Tirado-Sánchez A. Sporotrichin skin test for the diagnosis of sporotrichosis. J Fungi. 2018;4:55. doi: 10.3390/jof4020055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Malaria—diagnosis & treatment in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/diagnosis.html Available from:

- 47.Schallig H.D.F.H., Hu R.V.P., Kent A.D., van Loenen M., Menting S., Picado A. Evaluation of point of care tests for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Suriname. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:25. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3634-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mendonça L.S.O., Santos J.M., Kaneto C.M., de Carvalho L.D., Lima-Santos J., Augusto D.G. Characterization of serum cytokines and circulating microRNAs that are predicted to regulate inflammasome genes in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. Exp Parasitol. 2020;210:107846. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2020.107846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taslimi Y., Agbajogu C., Brynjolfsson S.F., Masoudzadeh N., Mashayekhi V., Gharibzadeh S. Profiling inflammatory response in lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis patients using a non-invasive sampling method combined with a high-throughput protein detection assay. Cytokine. 2020;130:155056. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nawas Z.Y., Tong Y., Kollipara R., Peranteau A.J., Woc-Colburn L., Yan A.C. Emerging infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations: viral and bacterial infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan H.B.Y., How C.H., Ng C.W.M. Definitive tests for dengue fever: when and which should I use? Singap Med J. 2017;58:632–635. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2017100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaki S.R., Shieh W.-J., Greer P.W., Goldsmith C.S., Ferebee T., Katshitshi J. A novel immunohistochemical assay for the detection of Ebola virus in skin: implications for diagnosis, spread, and surveillance of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:S36–S47. doi: 10.1086/514319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ebola virus disease. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/diagnosis/index.html Available from:

- 54.Mindel A., Carney O., Williams P. Cutaneous herpes simplex infections. Genitourin Med. 1990;66:14–15. doi: 10.1136/sti.66.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization. Herpes simplex virus. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus Available from:

- 56.Cubie H.A. Diseases associated with human papillomavirus infection. Virology. 2013;445:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gheit T. Mucosal and cutaneous human papillomavirus infections and cancer biology. Front Oncol. 2019;9:355. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika virus—symptoms, testing & treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/symptoms/diagnosis.html Available from:

- 59.World Health Organization Zika virus. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zika-virus Available from:

- 60.Ventrelli L., Marsilio Strambini L., Barillaro G. Microneedles for transdermal biosensing: current picture and future direction. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4:2606–2640. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie L., Zeng H., Sun J., Qian W. Engineering microneedles for therapy and diagnosis: a survey. Micromachines. 2020;11:271. doi: 10.3390/mi11030271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vranić E., Tucak A., Sirbubalo M., Rahić O., Elezović A., Hadžiabdić J. Microneedle-based sensor systems for real-time continuous transdermal monitoring of analytes in body fluids. IFMBE Proc. 2020;73:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang J., Liu X., Fu Y., Song Y. Recent advances of microneedles for biomedical applications: drug delivery and beyond. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dixon R.V., Lau W.M., Moghimi S.M., Ng K.W. The diagnostic potential of microneedles in infectious diseases. Precis Nanomed. 2020;3:629–640. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takeuchi K., Kim B. Functionalized microneedles for continuous glucose monitoring. Nano Converg. 2018;5:28. doi: 10.1186/s40580-018-0161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chinnadayyala S.R., Park K.D., Cho S. Review-in vivo and in vitro microneedle based enzymatic and non-enzymatic continuous glucose monitoring biosensors. ECS J Solid State Sci Technol. 2018;7:Q3159–Q3171. [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Laboudi A., Oliver N.S., Cass A., Johnston D. Use of microneedle array devices for continuous glucose monitoring: a review. Diabetes Technol Therapeut. 2013;15:101–115. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaushik S., Hord A.H., Denson D.D., McAllister D.V., Smitra S., Allen M.G. Lack of pain associated with microfabricated microneedles. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:502–504. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200102000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chua B., Desai S.P., Tierney M.J., Tamada J.A., Jina A.N. Effect of microneedles shape on skin penetration and minimally invasive continuous glucose monitoring in vivo. Sens Actuators Phys. 2013;203:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vicente-Perez E.M., Larrañeta E., McCrudden M.T.C., Kissenpfennig A., Hegarty S., McCarthy H.O. Repeat application of microneedles does not alter skin appearance or barrier function and causes no measurable disturbance of serum biomarkers of infection, inflammation or immunity in mice in vivo. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2017;117:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2017.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xue P., Zhang L., Xu Z., Yan J., Gu Z., Kang Y. Blood sampling using microneedles as a minimally invasive platform for biomedical diagnostics. Appl Mater Today. 2018;13:144–157. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang P.M., Cornwell M., Prausnitz M.R. Minimally invasive extraction of dermal interstitial fluid for glucose monitoring using microneedles. Diabetes Technol Therapeut. 2005;7:131–141. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gholami S., Mohebi M.M., Hajizadeh-Saffar E., Ghanian M.H., Zarkesh I., Baharvand H. Fabrication of microporous inorganic microneedles by centrifugal casting method for transdermal extraction and delivery. Int J Pharm. 2019;558:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fonseca D.F.S., Vilela C., Silvestre A.J.D., Freire C.S.R. A compendium of current developments on polysaccharide and protein-based microneedles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;136:704–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharma S., Hatware K., Bhadane P., Sindhikar S., Mishra D.K. Recent advances in microneedle composites for biomedical applications: advanced drug delivery technologies. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;103:109717. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu G.-S., Kong Y., Wang Y., Luo Y., Fan X., Xie X. Microneedles for transdermal diagnostics: recent advances and new horizons. Biomaterials. 2020;232:119740. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.National Health Service, UK Tuberculosis (TB)—Diagnosis. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/tuberculosis-tb/diagnosis/ Available from:

- 78.Open database: clinicaltrials.gov [Internet] 2013. Hospices Civils de Lyon, optimisation of tuberculosis intradermal skin test (TB Dermatest)https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01611844 Identifier: NCT01611844. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 79.Open database: clinicaltrials.gov [Internet] 2020. The HIV Netherlands Austria Thailand research collaboration, microneedles for diagnosis of LTBI.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04552015 Identifier: NCT04552015. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strambini L.M., Longo A., Scarano S., Prescimone T., Palchetti I., Minunni M. Self-powered microneedle-based biosensors for pain-free high-accuracy measurement of glycaemia in interstitial fluid. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;66:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li C.G., Joung H.A., Noh H., Song M.B., Kim M.G., Jung H. One-touch-activated blood multidiagnostic system using a minimally invasive hollow microneedle integrated with a paper-based sensor. Lab Chip. 2015;15:3286–3292. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00669d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jina A., Tierney M.J., Tamada J.A., McGill S., Desai S., Chua B. Design, development, and evaluation of a novel microneedle array-based continuous glucose monitor. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8:483–487. doi: 10.1177/1932296814526191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li C.G., Lee C.Y., Lee K., Jung H. An optimized hollow microneedle for minimally invasive blood extraction. Biomed Microdevices. 2013;15:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s10544-012-9683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blicharz T.M., Gong P., Bunner B.M., Chu L.L., Leonard K.M., Wakefield J.A. Microneedle-based device for the one-step painless collection of capillary blood samples. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:151–157. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ganesan A.V., Kumar D.K., Banerjee A., Swaminathan S. 13th IEEE international conference on nanotechnology. IEEE-NANO 2013; Beijing: 2013. MEMS based microfluidic system for HIV detection; pp. 557–560. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Donnelly R.F., Singh T.R.R., Garland M.J., Migalska K., Majithiya R., McCrudden C.M. Hydrogel-forming microneedle arrays for enhanced transdermal drug delivery. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:4879–4890. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201200864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Caffarel-Salvador E., Brady A.J., Eltayib E., Meng T., Alonso-Vicente A., Gonzalez-Vazquez P. Hydrogel-forming microneedle arrays allow detection of drugs and glucose in vivo: potential for use in diagnosis and therapeutic drug monitoring. PLoS One. 2016;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen J., Wang M., Ye Y., Yang Z., Ruan Z., Jin N. Fabrication of sponge-forming microneedle patch for rapidly sampling interstitial fluid for analysis. Biomed Microdevices. 2019;21:63. doi: 10.1007/s10544-019-0413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arevalo M.T., Rizzo G.M., Polsky R., Glaros T., Mach P.M. Proteomic characterization of immunoglobulin content in dermal interstitial fluid. J Proteome Res. 2019;18:2381–2384. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miller P.R., Taylor R.M., Tran B.Q., Boyd G., Glaros T., Chavez V.H. Extraction and biomolecular analysis of dermal interstitial fluid collected with hollow microneedles. Commun Biol. 2018;1:173. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0170-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taylor R.M., Miller P.R., Ebrahimi P., Polsky R., Baca J.T. Minimally-invasive, microneedle-array extraction of interstitial fluid for comprehensive biomedical applications: transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, exosome research, and biomarker identification. Lab Anim. 2018;52:526–530. doi: 10.1177/0023677218758801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]