Abstract

As the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) continues to surge worldwide, our knowledge of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is rapidly expanding. Although most COVID‐19 patients recover within weeks of symptom onset, some experience lingering symptoms that last for months (“long COVID‐19”). Early reports of COVID‐19 sequelae, including cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurological conditions, have raised concerns about the long‐term effects of COVID‐19, especially in hard‐hit communities. It is becoming increasingly evident that cancer patients are more susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and are at a higher risk of severe COVID‐19 than the general population. Nevertheless, whether long COVID‐19 increases the risk of cancer in those with no prior malignancies, remains unclear. Given, the disproportionate impact of the disease on the African American community, yet another unanswered question is whether racial disparities are to be expected in COVID‐19 sequelae. Herein, we propose that long COVID‐19 may predispose recovered patients to cancer development and accelerate cancer progression. This hypothesis is based on growing evidence of the ability of SARS‐CoV‐2 to modulate oncogenic pathways, promote chronic low‐grade inflammation, and cause tissue damage. Comprehensive studies are urgently required to elucidate the effects of long COVID‐19 on cancer susceptibility.

Keywords: cancer, COVID‐19 sequelae, health disparities, long COVID‐19, SARS‐CoV‐2

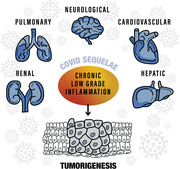

COVID‐19 sequelae are thought to result from chronic low‐grade inflammation triggered by the immunomodulatory effects of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. Since chronic inflammation is long‐established to be a driver of oncogenesis, we hypothesize that cancer development can be a COVID‐19 sequela, and briefly discuss how to test it.

INTRODUCTION

The unabated spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) poses significant challenges to healthcare and financial systems worldwide. Although many coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients recover within 2–6 weeks of symptom onset, some, known in social parlance as “long‐haulers,” experience lingering symptoms that ebb and flow for months. “Long COVID‐19” may not be uncommon among critically ill patients requiring intensive care; however, a significant number of long‐haulers are mild to moderate cases with no comorbidities or known risk factors. Initial findings from the UK COVID Symptom Study suggest that about 10% of COVID‐19 patients experience prolonged symptoms (beyond 3 weeks) and that in 1·5%–2% of patients, symptoms continue for over 90 days.[ 1 , 2 ] The consensus is that cases with symptoms lasting over 12 weeks are considered chronic COVID‐19.[ 1 ] A smaller study in Italy revealed that 87·4% of recovered patients reported persistence of at least one symptom, with fatigue, dyspnea, joint pain, and chest pain being the most frequently reported.[ 3 ] In another prospective study in Germany, cardiac involvement (78%) and ongoing myocardial inflammation (60%) were observed in most recovered patients, many of whom (60%) had a home‐based recovery.[ 4 ] Pulmonary fibrosis is also common in patients after recovery, even among those with no previous lung disorders.[ 5 ] Muscular pain, insomnia, tingling sensation, and neurological symptoms (e.g., headaches, dizziness, loss of taste and smell, brain fog, depression) have also been reported in long‐haulers.[ 6 ] These reports raise concerns about COVID‐19 sequelae, including long‐term cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurological conditions (e.g., cognitive decline, neurodegenerative diseases[ 6 , 7 ]), which can impact the quality of life long after viral clearance. Long‐term bone and lung damage, chronic fatigue, and neurological sequelae have also been observed with other respiratory viruses, including Influenza A (H7N9), SARS, and MERS.[ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]

ATTRIBUTES OF LONG COVID‐19

COVID‐19 is a multisystem disease with wide‐ranging symptoms and a highly heterogeneous clinical course. Host immunity overdrive in response to the virus can contribute to severe disease. Excessive proinflammatory cytokine release (cytokine storm) and multi‐organ coagulation abnormalities are hallmarks of severe COVID‐19 and can inflict extensive tissue damage.[ 11 ] However, the time required for immune homeostasis restoration after virus elimination, as well as the underlying mechanisms, remain unknown. Long COVID‐19 may be a direct consequence of low titer residual virus sequestered away in certain organs (e.g., in the brain[ 12 ]), though evading detection by current diagnostic methods. The more widely accepted rationale for long COVID‐19 is that the virus exerts long‐lasting immunomodulatory effects and causes chronic low‐grade inflammation.[ 6 , 13 , 14 ] Whether long COVID‐19 is a direct result of persistent viral attacks on multiple organs or a secondary consequence of a viral‐induced aberrant immune response is yet to be ascertained and warrants a deeper investigation. The latter premise is supported by the occurrence of chronic fatigue symptoms in long‐haulers that have been likened to myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), a hard to define condition that is believed to arise from persistent low‐grade inflammation.[ 15 , 16 ]

Chronic low‐grade inflammation in long‐haulers may facilitate the development of various illnesses. Prevailing or contiguous long‐hauler symptoms can foretell imminent disease sequelae (e.g., cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurological conditions). But what about sequelae in the offing, with no immediate discernible symptoms? Cancer development is one such foreseeable COVID‐19 sequelae since chronic inflammation is long‐established to be a fertile ground for oncogenesis. Interestingly, ME has been observed in patients with infectious mononucleosis caused by Epstein–Barr virus, a known oncovirus.[ 17 ] The association between viral infections and several cancers is well known and chronic inflammation and immune escape are some of the mechanisms driving oncogenic transformation.[ 18 ]

CAN CANCER BE A COVID‐19 SEQUELA?

Immune responses in COVID‐19 patients are orchestrated by proinflammatory cytokines (IL‐1, IL‐6, IL‐8, and TNF‐α), which are also known to drive tumorigenesis.[ 19 ] Additionally, COVID‐19 has been associated with T‐cell depletion and activation of oncogenic pathways, including JAK‐STAT, MAPK, and NF‐κB, potentially increasing the risk of cancer development.[ 20 ] Hypoxia due to inflammation or virus‐induced angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 depletion can induce oxidative stress and malignant transformation.[ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ] Over time, both chronic inflammation and oxidative stress can lead to DNA damage and subsequent carcinogenesis.[ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ] Moreover, COVID‐19 is known to cause multiorgan damage,[ 32 ] and extensive tissue damage is an oncogenic driver.

Studies on the closely related SARS coronavirus suggest a potential link between SARS‐CoV‐2 and cellular transformation. The SARS‐CoV non‐structural protein 3 (Nsp3) has been implicated in the degradation of the tumor suppressor protein p53.[ 33 ] Additionally, the SARS‐CoV endoribonuclease Nsp15 interacts with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRb), promoting its degradation via the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway.[ 34 ] Furthermore, an interaction between the S2 subunit of SARS‐CoV‐2 and the p53 and BRCA1/2 proteins has been demonstrated in silico.[ 35 ] The loss of these cellular caretakers and gatekeepers can lead to genomic instability and aberrant cell growth.[ 36 , 37 , 38 ]

Bouhaddou et al. have recently mapped changes in the phosphorylation status of host and viral proteins upon SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. They found phosphorylation alterations in 12% of interacting host proteins and identified the responsible kinases, some of which regulate cell shape and p38/MAPK pathway activation.[ 39 ] Interestingly, multinucleate giant cells have been observed in the milieu of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells.[ 40 ] Although most of these infected cells undergo apoptosis, a subset of cells may survive post‐viral clearance; nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the phosphorylation status of host proteins is restored to its original state or if this aberrant phosphorylation eventually leads to tumorigenesis.

Cancer development is rarely a result of an isolated event; it is a consequence of mutagenic events accumulated over a long period of time. It is fathomable that in tandem with other carcinogenic events, COVID‐19 may predispose the body to cancer development and accelerate cancer progression.

ARE RACIAL DISPARITIES TO BE EXPECTED IN COVID‐19 SEQUELAE?

African Americans (AAs) are disproportionately affected by COVID‐19, likely due to interacting biological, environmental, and social factors.[ 41 ] Immunogenetic differences also exist among populations, affecting the immune cell repertoire and resulting in racial differences in immune profiles. For instance, variations in serum cytokine levels between AAs and European Americans (EAs) have been observed. AAs are significantly more likely to carry genetic variants of proinflammatory cytokines.[ 42 , 43 ] Furthermore, aggravatingly, they often bear genotypes (including variants of IL‐1, IL‐6, IL‐10, and TNF‐α) known to tamp down the anti‐inflammatory responses.[ 42 ] Consistently, various inflammatory diseases are more common among AAs.[ 44 ] These immunogenetic differences may also explain why AAs have a higher risk of developing lung cancer than EAs.[ 45 ]

AAs have been subject to marginalization and discrimination, resulting in socio‐economic and health disparities. The engendered stress causes the release of inflammatory mediators (e.g., CRP, IL‐6, NF‐κB, TNF‐α) via the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis.[ 46 ] Continuous social and environmental stresses induce chronic inflammation that is at the root of most disease etiologies. Importantly, a higher prevalence of low‐grade inflammation has been shown in young AAs subjected to racial discrimination compared to those who identified positively with their racial identities.[ 47 ] Environmental and social factors may also modulate epigenetic modifications (DNA methylation, histone modifications, and alterations in the expression of non‐coding RNAs), thereby affecting disease susceptibility.[ 46 ] Considering the higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines in AAs, a pronounced impact of COVID‐19 is comprehensible. It remains unclear, however, whether AAs are more susceptible to COVID‐19 sequelae, including cancer.

Given that chronic, low‐grade inflammation is common in COVID‐19 patients, we hypothesize that COVID‐19, especially long COVID‐19, increases the risk of cancer. The immunogenetic differences among AAs and EAs may contribute to racial disparities in the oncogenic effects of COVID‐19. Ongoing experiments in our laboratory, alongside longitudinal clinical and community follow‐up studies, have been set in motion to assess COVID‐19‐evoked cancer risk, particularly in a race‐dependent manner.

LABORATORY AND COMMUNITY TESTBEDS

Proof‐of‐concept experiments are underway in our laboratory to assess the race‐dependent cytokine profiles in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected race‐annotated (AA and EA) primary epithelial and cancerous cell lines by employing cytokine arrays. Morphological alterations and changes in the levels of cancer‐related proteins (e.g., p53, pRB, BRCA1/2, NF‐κB) upon SARS‐CoV‐2 infection will be compared between AA‐ and EA‐derived cells. These findings will unveil any race‐dependent direct oncogenic effects of SARS‐CoV‐2. Moreover, these experiments will provide insight into the potential impact of COVID‐19 on cancer progression in patients with concurrent malignancies and identify potential racial disparities.

The effect of COVID‐19 on cancer outcomes, disease progression, metastasis, and relapse will be evaluated in longitudinal observational studies of cancer patients who were diagnosed with COVID‐19. Stratified analyses will be performed to assess the prognostic significance of COVID‐19 in cancer patients.

To assess the long‐term race‐dependent effects of COVID‐19 on cancer susceptibility through epidemiological studies, we will reach out to the AA community via faith‐based organizations and social media. We have developed a 20‐min comprehensive online survey to evaluate various health, socio‐economic and disease (e.g., disease course, duration, symptoms, comorbidities) parameters of long COVID in the AA community in Georgia State. Depending on early results, a large‐scale survey will be conducted. AAs are severely under‐represented in citizen science and mutual support groups on social media and private sites. We are working on reaching out to members of these groups and creating a safe and interactive space to engage effectively with the community and assess COVID‐19 sequelae in long‐haulers.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Given the rapidly expanding number of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals worldwide, assessing the COVID‐19 sequelae through well‐thought‐out, long‐term clinical studies is crucial. Reinfection cases have already been reported, yet the impact of reinfection on the sequelae is unknown. The health and financial burdens imposed by COVID‐19 have left the world reeling. Long COVID threatens to further impair physical and mental well‐being, thereby weakening the already fragile healthcare systems and increasing medical liabilities. It is conceivable that, though not being a traditional oncovirus that integrates into the host genome, SARS‐CoV‐2 establishes an oncogenic environment by instigating the host's immunity. Thus, great attention needs to be allotted towards understanding and quelling the immune dissonance within.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institutes of Health (R01CA239120) to R.A.

Saini, G. , & Aneja, R. (2021). Cancer as a prospective sequela of long COVID‐19. BioEssays, 43, e2000331. 10.1002/bies.202000331

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Greenhalgh, T. , Knight, M. , A'court, C. , Buxton, M. , & Husain, L. (2020). Management of post‐acute covid‐19 in primary care. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 370, m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Honigsbaum, M. , & Krishnan, L. (2020). Taking pandemic sequelae seriously: From the Russian influenza to COVID‐19 long‐haulers. Lancet, 396(10260), 1389–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carfì, A. , Bernabei, R. , & Landi, F. (2020). Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID‐19. JAMA, 324(6), 603–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puntmann, V. O. , Carerj, M. L , Wieters, I. , Fahim, M. , Arendt, C. , Hoffmann, J. , Shchendrygina, A. , Escher, F. , Vasa‐Nicotera, M. , Zeiher, A. M. , Vehreschild, M. , & Nagel, E. (2020). Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiology, 5(11), 1265–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao, Y.‐M , Shang, Y.‐M. , Song, W.‐B. , Li, Q.‐Q. , Xie, H. , Xu, Q.‐F. , Jia, J.‐L. , Li, L.‐M. , Mao, H.‐L. , Zhou, X.‐M. , Luo, H. , Gao, Y.‐F. , & Xu, A.‐G. (2020). Follow‐up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID‐19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine, 25, 100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall, M. (2020). The lasting misery of coronavirus long‐haulers. Nature, 585(7825), 339–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fotuhi, M. , Mian, A. , Meysami, S. , & Raji, C. A. (2020). Neurobiology of COVID‐3. Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 76(1), 3–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moldofsky, H. , & Patcai, J. (2011). Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post‐SARS syndrome; a case‐controlled study. BMC Neurology [Electronic Resource], 11, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang, P. , Li, J. , Liu, H. , Han, N. , Ju, J. , Kou, Y. , Chen, L. , Jiang, M. , Pan, F. , Zheng, Y. , Gao, Z. , & Jiang, B. (2020). Long‐term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital‐acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: A 15‐year follow‐up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Research, 8, 8. Erratum in: Bone Res 2020; 8:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen, J. , Wu, J. , Hao, S. , Yang, M. , Lu, X. , Chen, X. , & Li, L. (2017). Long term outcomes in survivors of epidemic Influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. Scientific Reports, 7, 17275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tay, M. Z. , Poh, C. M. , Rénia, L. , Macary, P. A. , & Ng, L. F. P. (2020). The trinity of COVID‐19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nature Reviews Immunology, 20, 363–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumari, P. , Rothan, H. A. , Natekar, J. P. , Stone, S. , Pathak, H. , Strate, P. G. , Arora, K. , Brinton, M. A. , & Kumar, M. (2021). Neuroinvasion and encephalitis following intranasal inoculation of SARS‐CoV‐2 in K18‐hACE2 mice. Viruses, 13(1), 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldberg, E. , Podell, K. , Sodickson, D. K. , & Fieremans, E. (2020). The brain after COVID‐19: Compensatory neurogenesis or persistent neuroinflammation? EClinicalMedicine, 31, 100684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Late Sequelae of COVID‐19. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/97200/cdc_97200_DS1.pdf?. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 15. Rubin, R. (2020). As their numbers grow, COVID‐19 “Long Haulers” stump experts. JAMA, 324(14), 1381–1383. 10.1001/jama.2020.17709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerwyn, M. , & Maes, M. (2017). Mechanisms explaining muscle fatigue and muscle pain in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): A review of recent findings. Current Rheumatology Reports, 19(1), 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Epstein‐Barr, K. J. R. (2019). Virus induced gene‐2 upregulation identifies a particular subtype of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 7, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith, C. , & Khanna, R. (2018). Immune‐based therapeutic approaches to virus‐associated cancers. Current Opinion in Virology, 32, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Del Valle, D. M. , Kim‐Schulze, S. , Huang, H.‐H. , Beckmann, N. D. , Nirenberg, S. , Wang, B. , Lavin, Y. , Swartz, T. H. , Madduri, D. , Stock, A. , Marron, T. U. , Xie, H. , Patel, M. , Tuballes, K. , Van Oekelen, O. , Rahman, A. , Kovatch, P. , Aberg, J. A. , Schadt, E. , … Gnjatic, S. (2020). An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID‐19 severity and survival. Nature Medicine, 26(10), 1636–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li, G. , Fan, Y. , Lai, Y. , Han, T. , Li, Z. , Zhou, P. , Pan, P. , Wang, W. , Hu, D. , Liu, X. , Zhang, Q. , & Wu, J. (2020). Coronavirus infections and immune responses. Journal of Medical Virology, 92(4), 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hockel, M. (2001). Biological consequences of tumor hypoxia. Seminars in Oncology, 28(2 Suppl. 8), 36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vaupel, P. , & Harrison, L. (2004). Tumor hypoxia: causative factors, compensatory mechanisms, and cellular response. The Oncologist, 9, 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al Tameemi, W. , Dale, T. P. , Al‐Jumaily, R. M. K. , & Forsyth, N. R. (2019). Hypoxia‐modified cancer cell metabolism. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 7, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muz, B. , De La Puente, P. , Azab, F. , & Azab, A. K. (2015). The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia (Auckl), 3, 3–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abassi, Z. , Higazi, A. A. R. , Kinaneh, S. , Armaly, Z. , Skorecki, K. , & Heyman, S. N. (2020). ACE2, COVID‐19 infection, inflammation, and coagulopathy: Missing pieces in the puzzle. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 574753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chaudhary, M. , Bajaj, S. , Bohra, S. , Swastika, N. , & Hande, A. (2015). The domino effect: Role of hypoxia in malignant transformation of oral submucous fibrosis. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: JOMFP, 19(2), 122–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greten, F. R. , & Grivennikov, S. I. (2019). Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity, 51(1), 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang, W. , Van Gent, D. C. , Incrocci, L. , Van Weerden, W. M. , & Nonnekens, J. (2020). Role of the DNA damage response in prostate cancer formation, progression and treatment. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, 23, 24–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kiwerska, K. , & Szyfter, K. (2019). DNA repair in cancer initiation, progression, and therapy‐a double‐edged sword. Journal of Applied Genetics, 60(3‐4), 329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bernstein, C. , Prasad, A. R. , Nfonsam, V. , & Bernstein, H. (2013). DNA damage, DNA repair and cancer. In Chen C. (Ed.), New research directions in DNA repair. IntechOpen. 10.5772/53919. Retrieved from https://www.intechopen.com/books/new-research-directions-in-dna-repair/dna-damage-dna-repair-and-cancer [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turgeon, M.‐O. , Perry, N. J. S. , & Poulogiannis, G. (2018). DNA damage, repair, and cancer metabolism. Frontiers in Oncology, 8, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mokhtari, T. , Hassani, F. , Ghaffari, N. , Ebrahimi, B. , Yarahmadi, A. , & Hassanzadeh, G. (2020). COVID‐19 and multiorgan failure: A narrative review on potential mechanisms. Journal of Molecular Histology, 51(6), 613–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma‐Lauer, Y. , Carbajo‐Lozoya, J. , Hein, M. Y. , Müller, M. A. , Deng, W. , Lei, J. , Meyer, B. , Kusov, Y. , Von Brunn, B. , Bairad, D. R. , Hünten, S. , Drosten, C. , Hermeking, H. , Leonhardt, H. , Mann, M. , Hilgenfeld, R. , & Von Brunn, A. (2016). p53 down‐regulates SARS coronavirus replication and is targeted by the SARS‐unique domain and PLpro via E3 ubiquitin ligase RCHY1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(35), E5192–E5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhardwaj, K. , Liu, P. , Leibowitz, J. L. , & Kao, C. C . (2012). The coronavirus endoribonuclease Nsp15 interacts with retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Journal of Virology, 86(8), 4294–4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singh, N. , & Bharara Singh, A. (2020). S2 subunit of SARS‐nCoV‐2 interacts with tumor suppressor protein p53 and BRCA: An in silico study. Translational Oncology, 13(10), 100814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mantovani, F. , Collavin, L. , & Del Sal, G. (2019). Mutant p53 as a guardian of the cancer cell. Cell Death & Differentiation, 26, 199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ozaki, T. , & Nakagawara, A. (2011). Role of p53 in cell death and human cancers. Cancers (Basel), 3(1), 994–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gorodetska, I. , Kozeretska, I. , & Dubrovska, A. (2019). BRCA genes: The role in genome stability, cancer stemness and therapy resistance. Journal of Cancer, 10(9), 2109–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bouhaddou, M. , Memon, D. , Meyer, B. , White, K. M. , Rezelj, V. V. , Correa Marrero, M. , Polacco, B. J. , Melnyk, J. E. , Ulferts, S. , Kaake, R. M. , Batra, J. , Richards, A. L. , Stevenson, E. , Gordon, D. E. , Rojc, A. , Obernier, K. , Fabius, J. M. , Soucheray, M. , Miorin, L. , … Krogan, N. J. (2020). The global phosphorylation landscape of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Cell, 182(3), 685–712.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mason, R. J. (2020). Pathogenesis of COVID‐19 from a cell biology perspective. European Respiratory Journal, 55(4), 2000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saini, G. , Swahn, M. H. , & Aneja, R. (2021). Disentangling the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Health Disparities in African Americans: Biological, Environmental, and Social Factors. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 8(3), ofab064. 10.1093/ofid/ofab064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ness, R. B. (2004). Differential distribution of allelic variants in cytokine genes among African Americans and White Americans. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(11), 1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nédélec, Y. , Sanz, J. , Baharian, G. , Szpiech, Z. A. , Pacis, A. , Dumaine, A. , Grenier, J.‐C. , Freiman, A. , Sams, A. J. , Hebert, S. , Pagé Sabourin, A. , Luca, F. , Blekhman, R. , Hernandez, R. D. , Pique‐Regi, R. , Tung, J. , Yotova, V. , & Barreiro, L. B. (2016). Genetic ancestry and natural selection drive population differences in immune responses to pathogens. Cell, 167(3), 657–669.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brinkworth, J. F. , & Barreiro, L. B. (2014). The contribution of natural selection to present‐day susceptibility to chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disease. Current Opinion in Immunology, 31, 66–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pine, S. R. , Mechanic, L. E. , Enewold, L. , Bowman, E. D. , Ryan, B. M. , Cote, M. L. , Wenzlaff, A. S. , Loffredo, C. A. , Olivo‐Marston, S. , Chaturvedi, A. , Caporaso, N. E. , Schwartz, A. G. , & Harris, C. C. (2016). Differential serum cytokine levels and risk of lung cancer between African and European Americans. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 25(3), 488–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Saini, G. , Ogden, A. , Mccullough, L. E. , Torres, M. , Rida, P. , & Aneja, R. (2019). Disadvantaged neighborhoods and racial disparity in breast cancer outcomes: The biological link. Cancer Causes & Control, 30(7), 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brody, G. H. , Yu, T. , Miller, G. E. , & Chen, E. (2015). Discrimination, racial identity, and cytokine levels among African‐American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), 496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.