Abstract

Satellite nitrogen dioxide (NO2) measurements are used extensively to infer nitrogen oxide emissions and their trends, but interpretation can be complicated by background contributions to the NO2 column sensed from space. We use the step decrease of US anthropogenic emissions from the COVID‐19 shutdown to compare the responses of NO2 concentrations observed at surface network sites and from satellites (Ozone Monitoring Instrument [OMI], Tropospheric Ozone Monitoring Instrument [TROPOMI]). After correcting for differences in meteorology, surface NO2 measurements for 2020 show decreases of 20% in March–April and 10% in May–August compared to 2019. The satellites show much weaker responses in March–June and no decrease in July–August, consistent with a large background contribution to the NO2 column. Inspection of the long‐term OMI trend over remote US regions shows a rising summertime NO2 background from 2010 to 2019 potentially attributable to wildfires.

Key Points

COVID‐19 US shutdown led to 22%–26% reductions of surface NO2 in March–April 2020

Satellite NO2 data show muted response to COVID‐19 shutdown because of NO2 background contribution to tropospheric column sensed from space

Summertime NO2 background has been rising in the US over the past decade and complicates the interpretation of trends in satellite NO2 data

1. Introduction

Nitrogen oxide radicals (NOx ≡ NO + NO2) affect air quality in a number of ways. They drive the production of ozone and nitrate particulate matter and are responsible for acid and nitrogen deposition. Fossil fuel combustion is the main anthropogenic source of NOx. Lightning, soils, and wildfires are important natural sources. Satellite observations of tropospheric NO2 columns by solar backscatter, in particular from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) launched in 2004, have enabled global monitoring of NOx emissions and their trends (Duncan et al., 2016; Krotkov et al., 2016; Lamsal et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2003; Miyazaki et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2020; Stavrakou et al., 2008). The OMI observations over the contiguous United States (CONUS) show a 2005–2009 decrease consistent with the US EPA National Emission Inventory (NEI) and with the surface NO2 monitoring network (Lamsal et al., 2015; Russell et al., 2012), but no further decrease after 2009 despite continued decrease of NOx emissions according to the NEI (Jiang et al., 2018). It is not clear if this flattening of the NO2 trend in the OMI data reflects major errors in the NEI (Jiang et al., 2018) or an increasing contribution from background NO2 unrelated to surface anthropogenic NOx emissions (Silvern et al., 2019). This background could originate from lightning, aircraft, soils, wildfires, and long‐range transport of pollution (Zhang et al., 2012). Aircraft observations over the Southeast US in summer show that background NO2 above 2 km altitude could contribute 70%–80% of the summertime tropospheric NO2 column sensed by satellite (Travis et al., 2016), reflecting the increased sensitivity to NO2 with altitude as a result of gas, aerosol, and cloud scattering (Martin et al., 2002). Russell et al. (2012) showed a 10%–20% increase in OMI NO2 columns over remote western US regions from 2005 to 2011, but the causes of this increase are unclear.

The shutdown of the US economy during the COVID‐19 crisis provides an opportunity to investigate the response of the satellite NO2 observations to the abrupt NOx emission reductions. 40 out of 48 states in CONUS issued mandatory stay‐at‐home orders during March and April 2020 (Moreland et al., 2020), greatly decreasing emissions from transportation and to a lesser extent from industry. Liquid fuel consumption in the US dropped by 21% and coal consumption dropped by 25% in the second quarter of 2020 compared to 2019 (EIA, 2020). The drop extended into July–August, with liquid fuel consumption down by 10% relative to 2019 (EIA, 2021). Anthropogenic NOx emissions decreased by an estimated 10%–40% in major US cities in March–April (Goldberg et al., 2020; Keller et al., 2020; Naeger & Murphy, 2020; Xiang et al., 2020).

Here, we examine the response of NO2 satellite observations to the COVID‐19 shutdown in CONUS and compare it to trends in the NO2 surface monitoring network. This allows us to determine if satellites can accurately track changes in surface NOx emissions or if background NO2 plays a confounding role, thus addressing the conundrum posed by the flattening of the OMI NO2 trend over the past decade. We go on to further examine the 2005–2019 OMI trends in the context of the surface NO2 observations and the GEOS‐Chem model.

2. Data and Model

We use hourly surface measurements of NO2 concentrations from the EPA Air Quality System (AQS) accessed through the application programming interface (API, aqs.epa.gov/aqsweb/documents/data_api.html). The measurements are made by a chemiluminescence analyzer with a molybdenum converter, which has been reported to have interferences from NOx oxidation products (Dunlea et al., 2007; Reed et al., 2016), but we assume here that these do not affect the relative long‐term trends. For the 2019–2020 analysis, we only include AQS sites with data for each month in both 2019 and 2020, for a total of 328 sites. We average the data on a 0.5° × 0.625° grid, for a total of 252 grid cells, to define collocation with satellite data and for meteorological trend correction. For the 2005–2019 trend analysis, we only include grid cells with continuous AQS records over the period, for a total of 168 0.5° × 0.625° grid cells.

Satellite observations of tropospheric NO2 vertical column densities are from two instruments: Tropospheric Ozone Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) (2018‐present) (Veefkind et al., 2012) and OMI (2005‐present) (Levelt et al., 2006, 2018). Pixel resolutions are 3.5 × 5.5 km2 for TROPOMI (3.5 × 7 km2 before August 2019) and 13 × 24 km2 for OMI. The TROPOMI retrieval is the version 1 offline product (www.tropomi.eu/data-products/nitrogen-dioxide). We use two different OMI retrievals: the version 4 NASA NO2 product (disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/OMNO2_003/summary) (Lamsal et al., 2020) and the QA4ECV OMI NO2 retrieval from KNMI (www.temis.nl/airpollution/no2.php) (Boersma et al., 2018). Single‐retrieval detection limit is 5 × 1014 molec cm−2 for OMI (Ialongo et al., 2016) and 2.8 × 1014 molec cm−2 for TROPOMI (Tack et al., 2021). For both OMI and TROPOMI retrievals, we filter the data using the quality flags and only include observations with cloud fraction <0.2, surface albedo <0.3, solar zenith angle <75°, and view zenith angle <65°. We also exclude OMI data affected by the so‐called row anomaly. We average the satellite data on the same 0.5° × 0.625° grid as the AQS surface NO2 data. This does not resolve urban hotspots but still enables contrast between urban and rural regions (Silvern et al., 2019).

We use the GEOS‐Chem chemical transport model version 12.9.2 (doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3959279) to simulate the contribution of meteorology to changes in surface and column NO2 concentrations at AQS sites between 2019 and 2020, assuming the same anthropogenic emissions in both years in the model. GEOS‐Chem is driven by MERRA‐2 assimilated meteorological data from the NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO) and has been used in many studies of NOx sources and chemistry over the US (Fisher et al., 2016; Jaeglé et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016; Travis et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012). We conduct nested simulations over North America (126°–66°W, 13°–57°N) at a horizontal resolution of 0.5° × 0.625° with dynamic boundary conditions generated from a global simulation with 4° × 5° resolution. Emissions are from the NEI 2011 scaled to 2019 uniformly across all sectors using national emission totals (EPA, 2020). Open fire emissions for 2019 from GFED4 (van der Werf et al., 2017) are used for both 2019 and 2020 simulations and are a small source of NOx on the scale of CONUS (Silvern et al., 2019). Lightning NOx emissions vary from year to year as determined by MERRA‐2 deep convective mass fluxes (Murray, 2016), and the difference between 2019 and 2020 across CONUS is roughly consistent with satellite observations from the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) (Figure S1). Temperature‐ and precipitation‐dependent soil NOx emissions are calculated following Hudman et al. (2012). The GEOS‐Chem simulated NO2 concentrations are processed to generate tropospheric NO2 columns as would be measured by TROPOMI and OMI, taking into account overpassing time and averaging kernels.

Long‐term GEOS‐Chem simulations from 2005 to 2017 are from Silvern et al. (2019), using version 11‐02c of the model at 0.5° × 0.625° grid resolution driven by MERRA‐2 meteorology and including yearly NEI emission trends. Open fire emissions in that simulation are from the daily Quick Fire Emissions Database (QFED) (Darmenov & da Silva, 2013). Soil NOx emissions are decreased by 50% in the midwestern US in summer based on a comparison with OMI NO2 (Vinken et al., 2014). A full description of this long‐term GEOS‐Chem simulation is provided in Silvern et al. (2019).

3. Response of NO2 Concentrations to the COVID‐19 Shutdown

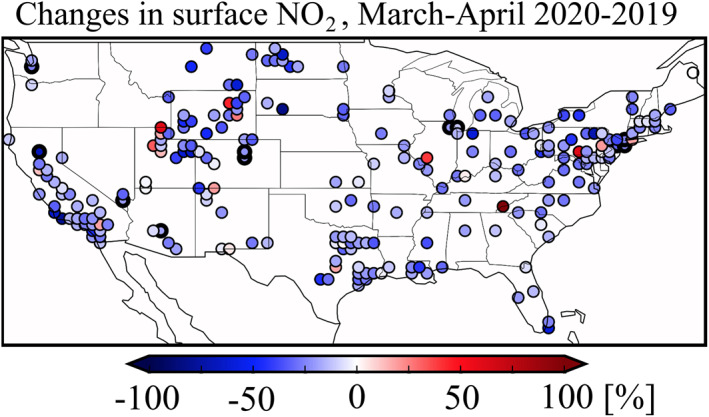

Figure 1 shows the relative changes in 24‐h average NO2 surface air concentrations measured at the AQS sites in March–April 2020 compared to March–April 2019. Most of the monitoring sites are in urban areas, though a number are in oil/gas production regions (Edwards et al., 2014). We expect the AQS NO2 trends to closely track NOx emission trends, after corrections for meteorology given below. The decreases in Figure 1 average 21% across CONUS with no apparent regional patterns. Thick‐rimmed circles identify the 0.5° × 0.625° grid cells with the 5% highest mean NO2 concentrations (exceeding 11 ppb) in March–April 2019. The decreases at these sites average 26%, similar to the CONUS average.

Figure 1.

Changes in 24‐h mean surface NO2 concentrations in March–April 2020 relative to March–April 2019. Observations are from the US EPA Air Quality System (AQS) network binned into 0.5° × 0.625° grid cells. Thick rims identify grid cells with the 5% highest concentrations in March–April 2019.

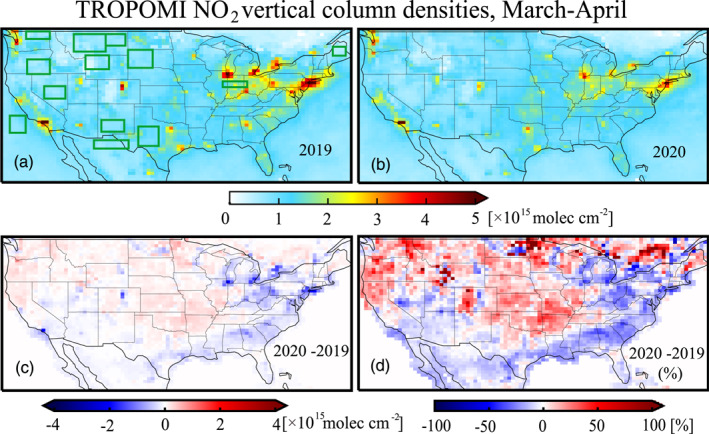

Figure S2 shows the changes in OMI NO2 vertical column densities between March and April 2019 and 2020. The data are noisy, presumably reflecting the degradation of the instrument in recent years (KNMI, 2020). Similar observations but with higher pixel resolution (3.5 × 5.5 km2 at nadir) are available from the TROPOMI satellite instrument launched in October 2017 (Griffin et al., 2019; Veefkind et al., 2012). Figure 2 shows the TROPOMI NO2 vertical column densities observed over CONUS in March–April 2019 and 2020 on the 0.5° × 0.625° grid. Differences between 2019 and 2020 are much less uniform than for the AQS sites, and large rural areas show increases. The average decrease from March to April 2019 to March–April 2020 is 4% across CONUS, 11% at the ensemble of AQS monitoring sites in Figure 1, and 21% at the AQS sites with 5% highest NO2. The weaker decrease of TROPOMI NO2 relative to the AQS data is consistent with a dampening effect from background NO2. The dampening effect is least where surface NO2 is highest.

Figure 2.

Mean tropospheric vertical column densities of NO2 measured by TROPOMI in March–April (a) 2019 and (b) 2020. Panels (c) and (d) show the absolute and relative differences between 2020 and 2019. The green rectangles in panel (a) represent the 13 remote regions used in the long‐term trend analysis of Figure 4b.

Variations in meteorology can be a confounding factor when interpreting year‐to‐year changes in concentrations (Goldberg et al., 2020). We diagnosed this meteorological influence in both AQS and satellite NO2 by conducting GEOS‐Chem simulations for 2019 and 2020 with no changes in anthropogenic and open fire emissions, but including changes in lightning and soil emissions (Section 2). Results are shown in Figure S3. Previous studies have shown that GEOS‐Chem can capture the synoptic‐scale temporal variability of ozone and particulate matter over the US (Fiore et al., 2003; Tai et al., 2012), suggesting that it should have some success in reproducing synoptically driven interannual variability. The consistency of lightning changes between 2019 and 2020 in GEOS‐Chem and the GLM data (Figure S1) supports the accounting of changes in background NO2. We find that meteorological influence leads to an average increase of 12% in March–April column NO2 from 2019 to 2020 for the top 5% AQS sites, which is close to the meteorological impact of 15% over major US cities from Goldberg et al. (2020). We subtract this model‐derived meteorological influence from the observed changes in what follows.

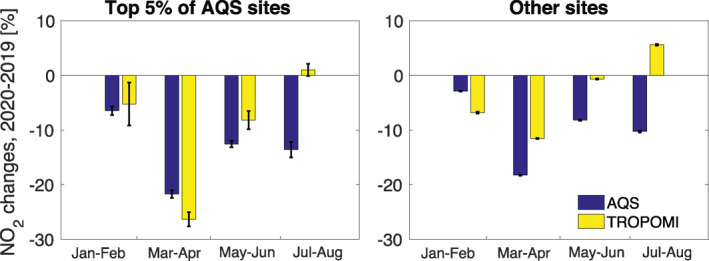

Figure 3 shows the mean meteorology‐corrected changes of NO2 concentrations at AQS sites for January–August 2020 relative to 2019 and the changes of TROPOMI tropospheric NO2 columns for the same sites. Here, we have again segregated the 5% of sites with the highest AQS NO2 concentrations, where the relative background influence would be expected to be least. For those sites, January–February 2020 (before the COVID‐19 shutdown) had 5% lower NO2 than the same period in 2019. The COVID‐19 shutdown decreased surface NO2 concentrations at these top 5% of AQS sites by 22% in March–April, 13% in May–June, and 14% in July–August. TROPOMI tracks these changes except in July–August where it shows no significant change in 2020 relative to 2019. For the other AQS sites, trends in surface NO2 concentrations are similar to the top 5% but TROPOMI shows no trend in May–June and an increase in July–August. We performed the same analysis with OMI data (Figure S4) and obtained similar results.

Figure 3.

Mean bimonthly changes in NO2 concentrations at AQS sites from 2019 to 2020. Changes in AQS surface air NO2 concentrations are compared to changes in TROPOMI tropospheric NO2 columns sampled at the same sites. Results for the AQS sites with the 5% highest 2019 NO2 concentrations on a 0.5° × 0.625° grid (Figure 1) are shown in the left panel. The effects of meteorological changes have been subtracted with a GEOS‐Chem simulation. The error bars represent the normalized standard errors of the changes averaged over the sites. AQS, Air Quality System; TROPOMI, Tropospheric Ozone Monitoring Instrument.

The results in Figure 3 show that TROPOMI is increasingly unable to capture the decrease of NOx emissions documented by the AQS sites in the seasonal progression from spring to summer. This is consistent with an obfuscating contribution of background NO2 from lightning, soils, and wildfires, which would be lowest in winter and highest in summer (Zhang et al., 2012).

4. Implications for the Long‐Term Trend of NO2 Observed From Satellite

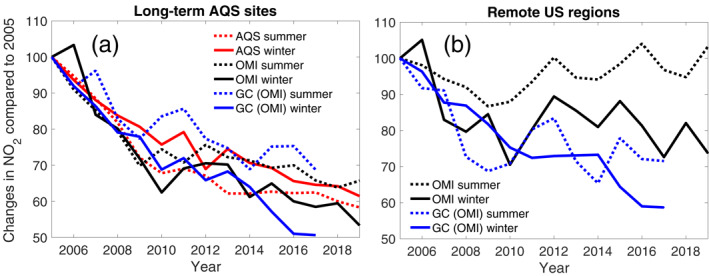

The muted response of the satellite NO2 observations to the COVID‐19 shutdown over CONUS implies a large background contribution to the tropospheric NO2 columns sensed from space. It supports the previous argument from Silvern et al. (2019) that the non‐decreasing NO2 background would have dampened the long‐term 2005–2017 trend of OMI NO2 averaged over CONUS relative to that expected from declining NOx emissions. We find little dampening when sampling OMI NO2 observations at grid cells with continuous AQS records for 2005–2019 (Figure 4a), which likely reflects the urban location of these long‐term sites (Figure S5). The OMI NO2 post‐2010 observations show a weaker trend in summer than winter that is not seen in the AQS data but is captured by GEOS‐Chem simulations. The weaker trend in summer is attributed in GEOS‐Chem to an increasing relative contribution of background NO2 as NOx emissions decrease.

Figure 4.

Long‐term trends in NO2 over CONUS, 2005–2019. (a) Trends averaged over the (mainly urban) AQS sites with continuous records of surface NO2 concentrations for 2005–2019 (Figure S5). The trends are relative to 2005 and shown separately for summer (JJA) and winter (DJF). Trends in OMI tropospheric NO2 columns (from the NASA retrieval) averaged over the same sites are also shown, along with a 2005–2017 GEOS‐Chem (GC) simulation of the OMI NO2 data previously reported by Silvern et al. (2019). (b) Trends in OMI and GEOS‐Chem tropospheric NO2 columns for summer and winter over 13 remote regions in the western US (Figure 2) as defined by Russell et al. (2012). CONUS, contiguous United States; OMI, Ozone Monitoring Instrument.

To better isolate the contribution of background NO2, we examined the long‐term OMI trends averaged over 13 remote regions in the western US previously defined by Russell et al. (2012) and shown in Figure 2. Results in Figure 4b indicate a decrease over 2005–2009 but not afterward. For the 2010–2019 period, OMI over these remote regions shows no trend in winter and a 19% increase in summer, implying a decadal rise in summertime background NO2 that GEOS‐Chem does not capture.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Better understanding of the NO2 background and its trend is needed for interpreting tropospheric NO2 satellite observations in terms of NOx emissions. That background cannot be easily subtracted from the satellite observations because it is not uniform (Marais et al., 2018, 2021). Cloud‐sliced satellite observations could isolate free tropospheric NO2 but need better accuracy than available at present (Choi et al., 2014; Marais et al., 2018). This may be achievable with TROPOMI (Marais et al., 2021) and with upcoming geostationary observations (Zoogman et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2018). The sensitivity of the retrievals to assumptions in the stratosphere‐troposphere separation of NO2 columns is small (Bucsela et al., 2013) and should not affect the trend or the difference between urban and rural scenes.

The observed decadal increase in US background NO2 likely cannot be explained by meteorological variability and instead reflect changes in intercontinental pollution transport or in natural emissions. However, this is not captured by GEOS‐Chem, which underestimates the free tropospheric NO2 over the contiguous US (Silvern et al., 2019; Travis et al., 2016). Anthropogenic NOx emissions over the past decade have increased in South Asia and the Middle East, but this would be offset by a decrease of emissions in East Asia (McDuffie et al., 2020) and the net effect would be simulated by GEOS‐Chem. Aircraft emissions have been increasing but their contributions to the NO2 column remain relatively small (Shah et al., 2021). There is no evidence for an increase in lightning over CONUS (Tippett et al., 2019). Soil emissions increase with rising temperature but that dependence would be simulated by GEOS‐Chem (Hudman et al., 2012).

One possible reason could be under‐accounting of the role of wildfires. Wildfire emissions in the western US are mostly in summer and have been increasing over the past decade (National Interagency Fire Center, 2021). GEOS‐Chem in its standard implementation emits all fire NOx in the boundary layer, but injections into the free troposphere from large fires with high NOx emission factors would have a much larger effect on NO2 columns measured from space (Alvarado et al., 2010; Paugam et al., 2016; Val Martin et al., 2010). This should be a focus of future model development.

In summary, we have used the unintended experiment of the COVID‐19 economic shutdown in the US starting in March 2020 to demonstrate the impact of background NO2 on interpreting NOx emission trends from satellite observations of NO2 vertical column densities. After subtracting the impact of meteorology in both surface and satellite NO2 observations, we find that the satellite observations can capture the magnitude of NOx emission reductions from March to June 2020 only for the sites with the highest levels of surface NO2. At other sites, the response of the satellite observations to the changes in emissions is strongly muted. The satellite data show no reduction in July–August 2020 when background NO2 is expected to be seasonally highest. Further inspection of long‐term trends in the satellite NO2 data over remote US regions shows a 2010–2019 increase in summer, implying a rise in background NO2 that is not captured by the GEOS‐Chem model. Under‐accounting of the influence of wildfires on tropospheric NO2 columns could be a factor. Better quantitative understanding of the factors contributing to background NO2 and its trend is urgently needed for the interpretation of satellite data, in particular from the upcoming geostationary constellation for air quality. An increasing trend in background NO2 could be key to explaining the current increasing trend in tropospheric ozone (Gaudel et al., 2018).

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NASA Earth Science Division as part of the Aura Science Team. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or the Department of Commerce. Although this paper has been reviewed by the EPA and approved for publication, it does not necessarily reflect EPA policies or views. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Patrick Campbell was supported by NOAA grant NA19NES4320002 (Cooperative Institute for Satellite Earth System Studies [CISESS]) at the University of Maryland/ESSIC.

Qu, Z. , Jacob, D. J. , Silvern, R. F. , Shah, V. , Campbell, P. C. , Valin, L. C. , & Murray, L. T. (2021). US COVID‐19 shutdown demonstrates importance of background NO2 in inferring NOx emissions from satellite NO2 observations. Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2021GL092783. 10.1029/2021GL092783

Data Availability Statement

The TROPOMI NO2 data are downloaded from http://www.tropomi.eu/data-products/nitrogen-dioxide (last access December 1, 2020). The OMI NO2 NASA product is downloaded from http://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/OMNO2_003/summary (last access December 1, 2020). The QA4ECV NO2 retrieval is from KNMI (https://www.temis.nl/airpollution/no2.php, last access April 4, 2021). Surface NO2 measurements are downloaded from EPA AQS accessed through the application programming interface: https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data (last access February 4, 2021).

References

- Alvarado, M. J. , Logan, J. A. , Mao, J. , Apel, E. , Riemer, D. , Blake, D. , et al. (2010). Nitrogen oxides and PAN in plumes from boreal fires during ARCTAS‐B and their impact on ozone: An integrated analysis of aircraft and satellite observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 10(20), 9739–9760. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/10/9739/2010/ [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, K. F. , Eskes, H. J. , Richter, A. , De Smedt, I. , Lorente, A. , Beirle, S. , et al. (2018). Improving algorithms and uncertainty estimates for satellite NO2 retrievals: Results from the quality assurance for the essential climate variables (QA4ECV) project. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 11(12), 6651–6678. https://amt.copernicus.org/articles/11/6651/2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Bucsela, E. J. , Krotkov, N. A. , Celarier, E. A. , Lamsal, L. N. , Swartz, W. H. , Bhartia, P. K. , et al. (2013). A new stratospheric and tropospheric NO2 retrieval algorithm for nadir‐viewing satellite instruments: Applications to OMI. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 6(10), 2607–2626. https://amt.copernicus.org/articles/6/2607/2013/ [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. , Joiner, J. , Choi, Y. , Duncan, B. N. , Vasilkov, A. , Krotkov, N. , & Bucsela, E. (2014). First estimates of global free‐tropospheric NO2 abundances derived using a cloud‐slicing technique applied to satellite observations from the Aura Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 14(19), 10565–10588. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/14/10565/2014/ [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W. J. , Moon, K.‐J. , Yoon, J. , Cho, A. , Kim, S.‐K. , Lee, S. , et al. (2018). Introducing the geostationary environment monitoring spectrometer. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing, 12(4), 1. 044005. 10.1117/1.JRS.12.044005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darmenov, A. , & da Silva, A. M. (2013). The Quick Fire Emissions Dataset (QFED) – Documentation of versions 2.1, 2.2 and 2.4. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, B. N. , Lamsal, L. N. , Thompson, A. M. , Yoshida, Y. , Lu, Z. , Streets, D. G. , et al. (2016). A space‐based, high‐resolution view of notable changes in urban NOx pollution around the world (2005–2014). Journal of Geophysical Research ‐ D: Atmospheres, 121(2), 976–996. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/2015JD024121 [Google Scholar]

- Dunlea, E. J. , Herndon, S. C. , Nelson, D. D. , Volkamer, R. M. , San Martini, F. , Sheehy, P. M. , et al. (2007). Evaluation of nitrogen dioxide chemiluminescence monitors in a polluted urban environment. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 7(10), 2691–2704. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/7/2691/2007/ [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P. M. , Brown, S. S. , Roberts, J. M. , Ahmadov, R. , Banta, R. M. , deGouw, J. A. , et al. (2014). High winter ozone pollution from carbonyl photolysis in an oil and gas basin. Nature, 514(7522), 351–354. 10.1038/nature13767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EIA . (2020). Short‐term Energy Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/tables/pdf/1tab.pdf [Google Scholar]

- EIA . (2021). Monthly world liquid fuels consumption, last access: Apr 3, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=46596#:∼:text=The%20U.S.%20Energy%20Information%20Administration,that%20dates%20back%20to%201980 [Google Scholar]

- EPA . (2020). Annual average emissions, air pollutant emission trends data, last access 11 August 2020. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/air-pollutant-emissions-trends-data [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, A. , Jacob, D. J. , Liu, H. , Yantosca, R. M. , Fairlie, T. D. , & Li, Q. (2003). Variability in surface ozone background over the United States: Implications for air quality policy. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(D24). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2003JD003855 [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J. A. , Jacob, D. J. , Travis, K. R. , Kim, P. S. , Marais, E. A. , Chan Miller, C. , et al. (2016). Organic nitrate chemistry and its implications for nitrogen budgets in an isoprene‐ and monoterpene‐rich atmosphere: Constraints from aircraft (SEAC4RS) and ground‐based (SOAS) observations in the Southeast US. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(9), 5969–5991. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/5969/2016/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudel, A. , Cooper, O. R. , Ancellet, G. , Barret, B. , Boynard, A. , Burrows, J. P. , et al. (2018). Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Present‐day distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone relevant to climate and global atmospheric chemistry model evaluation. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 6. 10.1525/elementa.291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D. L. , Anenberg, S. C. , Griffin, D. , McLinden, C. A. , Lu, Z. , & Streets, D. G. (2020). Disentangling the impact of the COVID‐19 lockdowns on urban NO2 from natural variability. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(17). e2020GL089269. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2020GL089269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D. , Zhao, X. , McLinden, C. A. , Boersma, F. , Bourassa, A. , Dammers, E. , et al. (2019). High‐resolution mapping of nitrogen dioxide with TROPOMI: First results and validation over the Canadian Oil Sands. Geophysical Research Letters, 46(2), 1049–1060. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2018GL081095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudman, R. C. , Moore, N. E. , Mebust, A. K. , Martin, R. V. , Russell, A. R. , Valin, L. C. , & Cohen, R. C. (2012). Steps toward a mechanistic model of global soil nitric oxide emissions: Implementation and space based‐constraints. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 12(16), 7779–7795. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/12/7779/2012/ [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo, I. , Herman, J. , Krotkov, N. , Lamsal, L. , Boersma, K. F. , Hovila, J. , & Tamminen, J. (2016). Comparison of OMI NO2 observations and their seasonal and weekly cycles with ground‐based measurements in Helsinki. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 9(10), 5203–5212. https://amt.copernicus.org/articles/9/5203/2016/ [Google Scholar]

- Jaeglé, L. , Shah, V. , Thornton, J. A. , Lopez‐Hilfiker, F. D. , Lee, B. H. , McDuffie, E. E. , et al. (2018). Nitrogen oxides emissions, chemistry, deposition, and export over the northeast United States during the WINTER aircraft campaign. Journal of Geophysical Research ‐ D: Atmospheres, 123(21), 12368–12393. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2018JD029133 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z. , McDonald, B. C. , Worden, H. , Worden, J. R. , Miyazaki, K. , Qu, Z. , et al. (2018). Unexpected slowdown of US pollutant emission reduction in the past decade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(20), 5099–5104. 10.1073/pnas.1801191115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, C. A. , Evans, M. J. , Knowland, K. E. , Hasenkopf, C. A. , Modekurty, S. , Lucchesi, R. A. , et al. (2020). Global impact of COVID‐19 restrictions on the surface concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and ozone. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions, 21(5), 1–32. https://acp.copernicus.org/preprints/acp-2020-685/ [Google Scholar]

- KNMI . (2020). Background information about the row anomaly in OMI. Retrieved from https://projects.knmi.nl/omi/research/product/rowanomaly-background.php [Google Scholar]

- Krotkov, N. A. , McLinden, C. A. , Li, C. , Lamsal, L. N. , Celarier, E. A. , Marchenko, S. V. , et al. (2016). Aura OMI observations of regional SO2 and NO2 pollution changes from 2005 to 2015. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(7), 4605–4629. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/4605/2016/ [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal, L. N. , Duncan, B. N. , Yoshida, Y. , Krotkov, N. A. , Pickering, K. E. , Streets, D. G. , & Lu, Z. (2015). U.S. NO2 trends (2005‐2013): EPA Air Quality System (AQS) data versus improved observations from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI). Atmospheric Environment, 110, 130–143. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1352231015002794 [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal, L. N. , Krotkov, N. A. , Vasilkov, A. , Marchenko, S. , Qin, W. , Yang, E. S. , et al. (2020). OMI/aura nitrogen dioxide standard product with improved surface and cloud treatments. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques Discussions, 14, 455–479. https://amt.copernicus.org/preprints/amt-2020-200/ [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal, L. N. , Martin, R. V. , Padmanabhan, A. , van Donkelaar, A. , Zhang, Q. , Sioris, C. E. , et al. (2011). Application of satellite observations for timely updates to global anthropogenic NOx emission inventories. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(5). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2010GL046476 [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.‐M. , Paulot, F. , Henze, D. K. , Travis, K. , Jacob, D. J. , Pardo, L. H. , & Schichtel, B. A. (2016). Sources of nitrogen deposition in Federal Class I areas in the US. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(2), 525–540. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/525/2016/ [Google Scholar]

- Levelt, P. F. , Joiner, J. , Tamminen, J. , Veefkind, J. P. , Bhartia, P. K. , Stein Zweers, D. C. , et al. (2018). The Ozone Monitoring Instrument: Overview of 14 years in space. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 18(8), 5699–5745. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/18/5699/2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Levelt, P. F. , van den Oord, G. H. J. , Dobber, M. R. , Malkki, A. , Huib Visser, V. , Johan de Vries, V. , et al. (2006). The ozone monitoring instrument. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 44(5), 1093–1101. 10.1109/tgrs.2006.872333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marais, E. A. , Jacob, D. J. , Choi, S. , Joiner, J. , Belmonte‐Rivas, M. , Cohen, R. C. , et al. (2018). Nitrogen oxides in the global upper troposphere: Interpreting cloud‐sliced NO2 observations from the OMI satellite instrument. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 18(23), 17017–17027. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/18/17017/2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Marais, E. A. , Roberts, J. F. , Ryan, R. G. , Eskes, H. , Boersma, K. F. , Choi, S. , et al. (2021). New Observations of upper tropospheric NO2 from TROPOMI. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 14, 2389–2408. https://amt.copernicus.org/articles/14/2389/2021/ [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. V. , Chance, K. , Jacob, D. J. , Kurosu, T. P. , Spurr, R. J. D. , Bucsela, E. , et al. (2002). An improved retrieval of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide from GOME. Journal of Geophysical Research, 107(D20). ACH 9‐1‐ACH 9‐21. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2001JD001027 [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. V. , Jacob, D. J. , Chance, K. , Kurosu, T. P. , Palmer, P. I. , & Evans, M. J. (2003). Global inventory of nitrogen oxide emissions constrained by space‐based observations of NO2 columns. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(D17). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2003JD003453 [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie, E. E. , Smith, S. J. , O'Rourke, P. , Tibrewal, K. , Venkataraman, C. , Marais, E. A. , et al. (2020). A global anthropogenic emission inventory of atmospheric pollutants from sector‐ and fuel‐specific sources (1970–2017): An application of the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Earth System Science Data, 12, 3413–3442. 10.5194/essd-12-3413-2020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, K. , Eskes, H. , Sudo, K. , Boersma, K. F. , Bowman, K. , & Kanaya, Y. (2017). Decadal changes in global surface NOx emissions from multi‐constituent satellite data assimilation. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 17(2), 807–837. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/17/807/2017/ [Google Scholar]

- Moreland, A. , Herlihy, C. , Tynan, M. A. , Sunshine, G. , McCord, R. F. , Hilton, C. , et al. (2020). Timing of state and territorial COVID‐19 stay‐at‐home orders and changes in population movement – United States, March 1–May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69, 1198–1203. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. T. (2016). Lightning NOx and impacts on air quality. Current Pollution Reports, 2(2), 115–133. 10.1007/s40726-016-0031-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naeger, A. R. , & Murphy, K. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 containment measures on air pollution in California. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 20, 2025–2034. 10.4209/aaqr.2020.05.0227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Interagency Fire Center . (2021). Total wildland fires and acres (1983–2020). last access April 7, 2021, Retrieved from https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/statistics/wildfires [Google Scholar]

- Paugam, R. , Wooster, M. , Freitas, S. , & Val Martin, M. (2016). A review of approaches to estimate wildfire plume injection height within large‐scale atmospheric chemical transport models. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(2), 907–925. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/907/2016/ [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z. , Henze, D. K. , Cooper, O. R. , & Neu, J. L. (2020). Improving NO2 and ozone simulations through global NOx emission inversions. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions, 20, 13109–13130. https://acp.copernicus.org/preprints/acp-2020-307/ [Google Scholar]

- Reed, C. , Evans, M. J. , Di Carlo, P. , Lee, J. D. , & Carpenter, L. J. (2016). Interferences in photolytic NO2 measurements: Explanation for an apparent missing oxidant? Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(7), 4707–4724. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/4707/2016/ [Google Scholar]

- Russell, A. R. , Valin, L. C. , & Cohen, R. C. (2012). Trends in OMI NO2 observations over the United States: Effects of emission control technology and the economic recession. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 12(24), 12197–12209. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/12/12197/2012/ [Google Scholar]

- Shah, V. (2021). Vertical distribution and sources of NO2 in the free troposphere: Implications for interpretation of OMI and TROPOMI NO2 data. 101st American Meteorological Society meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Silvern, R. F. , Jacob, D. J. , Mickley, L. J. , Sulprizio, M. P. , Travis, K. R. , Marais, E. A. , et al. (2019). Using satellite observations of tropospheric NO2 columns to infer long‐term trends in US NOx emissions: The importance of accounting for the free tropospheric NO2 background. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 19(13), 8863–8878. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/19/8863/2019/ [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakou, T. , Müller, J.‐F. , Boersma, K. F. , De Smedt, I. , & van der A, R. J. (2008). Assessing the distribution and growth rates of NOx emission sources by inverting a 10‐year record of NO2 satellite columns. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(10). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2008GL033521 [Google Scholar]

- Tack, F. , Merlaud, A. , Iordache, M.‐D. , Pinardi, G. , Dimitropoulou, E. , Eskes, H. , et al. (2021). Assessment of the TROPOMI tropospheric NO2 product based on airborne APEX observations. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 14(1), 615–646. https://amt.copernicus.org/articles/14/615/2021/ [Google Scholar]

- Tai, A. P. K. , Mickley, L. J. , & Jacob, D. J. (2012). Impact of 2000‐2050 climate change on fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air quality inferred from a multi‐model analysis of meteorological modes. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 12(23), 11329–11337. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/12/11329/2012/ [Google Scholar]

- Tippett, M. K. , Lepore, C. , Koshak, W. J. , Chronis, T. , & Vant‐Hull, B. (2019). Performance of a simple reanalysis proxy for U.S. cloud‐to‐ground lightning. International Journal of Climatology, 39(10), 3932–3946. https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/joc.6049 [Google Scholar]

- Travis, K. R. , Jacob, D. J. , Fisher, J. A. , Kim, P. S. , Marais, E. A. , Zhu, L. , et al. (2016). Why do models overestimate surface ozone in the Southeast United States? Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(21), 13561–13577. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/13561/2016/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Val Martin, M. , Logan, J. A. , Kahn, R. A. , Leung, F.‐Y. , Nelson, D. L. , & Diner, D. J. (2010). Smoke injection heights from fires in North America: Analysis of 5 years of satellite observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 10, 1491–1510. 10.5194/acp-10-1491-2010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf, G. R. , Randerson, J. T. , Giglio, L. , van Leeuwen, T. T. , Chen, Y. , Rogers, B. M. , et al. (2017). Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth System Science Data, 9(2), 697–720. https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/9/697/2017/ [Google Scholar]

- Veefkind, J. P. , Aben, I. , McMullan, K. , Förster, H. , de Vries, J. , Otter, G. , et al. (2012). TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel‐5 Precursor: A GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sensing of Environment, 120, 70–83. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0034425712000661 [Google Scholar]

- Vinken, G. C. M. , Boersma, K. F. , Maasakkers, J. D. , Adon, M. , & Martin, R. V. (2014). Worldwide biogenic soil NOx emissions inferred from OMI NO2 observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 14(18), 10363–10381. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/14/10363/2014/ [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J. , Austin, E. , Gould, T. , Larson, T. , Shirai, J. , Liu, Y. , et al. (2020). Impacts of the COVID‐19 responses on traffic‐related air pollution in a Northwestern US city. The Science of the Total Environment, 747. 141325. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , Jacob, D. J. , Knipping, E. M. , Kumar, N. , Munger, J. W. , Carouge, C. C. , et al. (2012). Nitrogen deposition to the United States: Distribution, sources, and processes. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 12(10), 4539–4554. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/12/4539/2012/ [Google Scholar]

- Zoogman, P. , Liu, X. , Suleiman, R. M. , Pennington, W. F. , Flittner, D. E. , Al‐Saadi, J. A. , et al. (2017). Tropospheric emissions: Monitoring of pollution (TEMPO). Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, 186, 17–39. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022407316300863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1

Data Availability Statement

The TROPOMI NO2 data are downloaded from http://www.tropomi.eu/data-products/nitrogen-dioxide (last access December 1, 2020). The OMI NO2 NASA product is downloaded from http://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/OMNO2_003/summary (last access December 1, 2020). The QA4ECV NO2 retrieval is from KNMI (https://www.temis.nl/airpollution/no2.php, last access April 4, 2021). Surface NO2 measurements are downloaded from EPA AQS accessed through the application programming interface: https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data (last access February 4, 2021).