Graphical abstract

Keywords: On-cell NMR, Natural-abundance NMR, Recognition mechanism, Integrin, Structure-dynamics-activity relationship, Molecular dynamics simulations, Molecular docking

Abstract

Structural investigations of receptor-ligand interactions on living cells surface by high-resolution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) are problematic due to their short lifetime, which often prevents the acquisition of experiments longer than few hours. To overcome these limitations, we developed an on-cell NMR-based approach for exploring the molecular determinants driving the receptor-ligand recognition mechanism under native conditions. Our method relies on the combination of high-resolution structural and dynamics NMR data with Molecular Dynamics simulations and Molecular Docking studies. The key point of our strategy is the use of Non Uniform Sampling (NUS) and T1ρ-NMR techniques to collect atomic-resolution structural and dynamics information on the receptor-ligand interactions with living cells, that can be used as conformational constraints in computational studies. In fact, the application of these two NMR methodologies allows to record spectra with high S/N ratio and resolution within the lifetime of cells. In particular, 2D NUS [1H–1H] trNOESY spectra are used to explore the ligand conformational changes induced by receptor binding; whereas T1ρ-based experiments are applied to characterize the ligand binding epitope by defining two parameters: T1ρ Attenuation factor and T1ρ Binding Effect. This approach has been tested to characterize the molecular determinants regulating the recognition mechanism of αvβ5-integrin by a selective cyclic binder peptide named RGDechi15D. Our data demonstrate that the developed strategy represents an alternative in-cell NMR tool for studying, at atomic resolution, receptor-ligand recognition mechanism on living cells surface. Additionally, our application may be extremely useful for screening of the interaction profiling of drugs with their therapeutic targets in their native cellular environment.

1. Introduction

The discovery of ligands able to discriminate among different receptor subtypes presenting high sequence and structure homology, but different biological effects, is a challenge in the biomedical field to gain drugs, without the side effects due to interactions with 'off-target' proteins [1], [2]. An approach to obtain highly target-selective ligands is the identification of novel scaffolds designed to bind to more than one site of the target receptor, thus providing therapeutic/diagnostic benefits. So far, the development of membrane receptor-binding ligands has relied on data from in vitro biophysical characterizations, in vivo or in cellulo biological assays or in silico structure-based receptor-ligand targeting approaches [3]. Of note, both in vitro and in silico techniques provide information on the receptor-ligand interactions under non-native conditions. Consequently, ligand properties characterized in absence of cellular environment may not reflect the efficacy that the ligand shows in vivo, where the presence of various cellular environmental factors can influence the receptor-ligand recognition mechanism.

Therefore, to identify binding epitopes or to decipher the mechanism of action of a particular ligand, it is extremely important to describe the structural, dynamics and functional features driving receptor-ligand interactions within a cellular environment. In this scenario, in-cell and on-cell Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (in-cell/on-cell NMR) represents a powerful technique for studying, at atomic resolution, protein–protein and protein–ligand interactions, directly in the intracellular environment or on the membrane surface of living cells[4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. In particular, in- and on-cell NMR methods based on the observations of ligands, including transfer NOESY (trNOESY) and saturation transfer difference (STD), are widely used to characterize binding of ligands to membrane receptors on the cell surface[9], [10], [11].

trNOESY NMR experiment is used to explore the ligand conformational changes induced by receptor binding; whereas STD NMR method is applied to characterize the ligand binding epitope revealing the closest bound moieties to the receptor. However, the application of both NMR techniques is strongly limited by the short lifetime of cells in an NMR sample tube, that does not allow to record spectra with high S/N ratio and resolution. For these reasons, the use of trNOESY and STD experiments for direct evaluation of receptor-ligand interactions under complex conditions with living cells is challenging. Therefore, in order to overcome these drawbacks, we developed an alternative NMR-based strategy that combines high-resolution structural and dynamics NMR data with Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and Molecular Docking studies. In details, our approach relies on the acquisition of 2D trNOESY spectra, using NUS in combination with spectral reconstruction by non-Fourier transform methods, for studying the ligand conformational changes, upon binding and on the measurement of 1D T1ρ experiments, as alternative tool to the STD NMR method, for defining the ligand binding epitope.

We applied this on-cell NMR approach to describe, at atomic resolution, the molecular determinants regulating the recognition mechanism of αvβ5 integrin by a selective cyclic binder peptide. Integrins are a family of transmembrane receptors composed of many subtypes, all arranged as heterodimers, generated by the combination of 18 α and 8 β different subunits that act as key receptors for cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix providing support for cells, regulating cell migration and reaction to the microenvironment. Genetic alteration or dysregulation of integrin expression are correlated with the onset of many human diseases[12]. Within integrins, the RGD–binding receptors αvβ3, αvβ5, and α5β1 constitute the key members of the family involved in all stages of cancer progression, including tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis[13]. Over the last decade, we designed and characterized a bi-functional peptide (RGDechi) including a cyclic RGD pentapeptide for integrins binding, covalently linked by a spacer at a C-terminal echistatin fragment to confer a high selectivity for the β3 receptor[14]. In vitro and in vivo studies[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23] proved the selective interaction of this peptide with αvβ3 integrin, and structural analysis, based on a combination of NMR and computational studies, using αvβ3 embedded in cancer cell membranes, highlighted the molecular details of the binding[19]. To validate the recognition model and the pivotal role of the hCit15 in the binding to the β3 chain, we designed a derivative named RGDechi15D, where hCit15 was replaced by an Asp residue. This substitution shifted the selectivity from αvβ3 to αvβ5, in accordance with the different amino acid composition of the two integrin subunits, and provided a novel αvβ5 antagonist as confirmed by in vitro studies[24].

Here, we report the first application of an alternative approach to investigate the structural details driving the formation of the αvβ5-RGDechi15D complex. Our strategy can be considered a general approach for the investigation of ligand-receptor interactions on living cells surface and can be eventually applied to a variety of other cellular interactions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Peptide synthesis

RGDechi15D was synthetized as previously reported [19]. The amino-acid sequence of the peptide is: K-R-G-D-e-M−D−D−P−G−R−N−P−H−D−G−P−A−T. The residues of the RGD cycle are underlined.

2.2. Cells preparation

Human adenocarcinoma cells line (HeLa) and human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) from ATCC, were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mm glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mgmL¢1 streptomycin (Euroclone, Italy). The cells at 80% confluence were detached with EDTA 0.1 mM in PBS to maintain the receptor integrity then were collected and re-suspended in PBS (1x107 cells/ mL) to perform NMR analyses.

2.3. Analysis of Caspase-3 activity

Determination of caspase-3 activity was performed by a fluorometric assay as described elsewhere [25].

2.4. Invasion assay

Cell invasion was assayed using transwell chambers coated with ECL Cell Attachment matrix (Millipore Corporation) as reported in a previous publication [20].

2.5. Cells viability and plating colony tests.

Cell viability was measured by Trypan blue exclusion test performed before and after NMR analysis. Briefly, cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of HBSS. 0.2 ml of cell suspension were added to 0.5 ml of PBS and 0.3 ml of 0.4% of Trypan blue solution (Lonza, Walkersville, MD USA). After 5 min at room temperature, cells were counted in a Burker’s chamber. Cell number was measured with a Zen 3.1 software. Cell viability was measured as % of live cells on total cells. Experiments have been performed in triplicate and five counts have been made for every sample. Results have been reported as mean % of live cells ± SEM. Afterwards, cell suspension was centrifuged, pellet was resuspended in the culture medium described above and plated in culture dish at 37 °C 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells were observed with an AxioVert 25 Microscope (Zeiss) and imaged by a Zen 3.1 software

2.6. Natural-abundance nuclear Magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

NMR natural-abundance experiments of RGDechi15D were performed by using a Bruker AVIII HD 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple resonance Prodigy N2 cryoprobe having z-axis pulse field gradient. NMR samples were prepared by dissolving the peptide in 200 μL of Hank’s balanced (HBSS) buffer pH 7.4 and 10% 2H2O in a 3-mm NMR tube. 1H, 15N and 13C chemical shift assignments were performed by using the optimized protocol reported in a previous publication[23]. Briefly, the following spectra were acquired and analyzed:

-

-

2D [1H–1H] Total Correlation SpectroscopY (TOCSY)[26], 2D [1H–1H] Nuclear Overhauser Effect SpectroscopY (NOESY)[27] and 2D [1H–1H] Rotating frame Overhauser Effect SpectroscopY (ROESY)[28] were acquired using 32 scans per t1 increment, a spectral width (SW) of 6001.33 Hz along both dimensions, a 3.0 s relaxation delay and 2048 × 256 complex points in t2 and t1, respectively. The 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY spectrum was measured using a homonuclear Hartmann-Hahn transfer through a MLEV17 sequence using a mixing time of 70 ms and 10 KHz spin-lock field strength. The 2D [1H–1H] NOESY experiment was acquired with a mixing time of 250 ms. The 2D [1H–1H] ROESY was carried out with a CW spin-lock field strength of 4 kHz, a mixing time of 250 ms and 5.0 s relaxation delay. In all bi-dimensional [1H–1H] experiments, water suppression was achieved by means of Watergate pulse sequence with gradients using double echo. All 2D spectra were apodized with a square cosine window function and zero fill to a matrix of size 4096 × 1024 before Fourier transform and baseline correction.

− 2D [1H-15N] Hetero-nuclear Single Quantum Coherence Spectroscopy (HSQC) experiment was recorded with 880 scans per t1 increment, a spectral width of 1581.26 Hz along t1 and 6001.33 Hz along t2, 2048 X 256 complex points in t2 and t1, respectively, and 1.0 s relaxation delay. The [1H-15N] HSQC was apodized with a square cosine window function and a zero filling to a matrix of size 4096 × 1024 before Fourier transform and baseline correction.

− 2D [1H–13C] Hetero-nuclear Single Quantum Coherence Spectroscopy (HSQC) spectrum was acquired with 800 scans per t1 increment, a spectral width of 5131.08 Hz along t1 and 6001.33 Hz along t2, 2048 X 200 complex points in t2 and t1, respectively, and 1.0 s relaxation delay. The [1H–13C] HSQC constant time version ([1H–13C] CT HSQC) pulse sequence was acquired with a coupling constant JXH = 145 Hz, constant time period of 13.3 ms. The [1H–13C] CT HSQC was apodized with a square cosine window function and zero fill to a matrix of size 4096 × 4096 before Fourier transform and baseline correction.

Natural-abundance NMR measurements for characterizing the RGDechi15D backbone dynamics were performed at 600 MHz and T = 298 K. The acquisition parameters of the NMR experiments used to describe the backbone motions are described below:

-

-

2D T2-filter [1H-15N] Hetero-nuclear Single Quantum Coherence Spectroscopy (HSQC) experiment was recorded with 880 scans per t1 increment, a spectral width of 1581.26 Hz along t1 and 6001.33 Hz along t2, 2048 X 128 complex points in t2 and t1, respectively, and 1.0 s relaxation delay. The [1H-15N] T2-filter HSQC experiments were measured by using two different relaxation-compensated CPMG periods (125 ms and 250 ms). The T2 filter [1H-15N] HSQC was apodized with a square cosine window function and a zero filling to a matrix of size 4096x1024 before Fourier transform and baseline correction.

Amide temperature coefficients and 3JHNHα couplings constants were obtained by measuring one-dimensional (1D) 1H spectra with the following acquisition parameters: spectral width of 7211.54 Hz, relaxation delay 1.0 s, 7 K data points for acquisition and 16 K for transformation.

All 2D NMR spectra were processed by using NMRPipe[29] and analyzed using SPARKY[30] and CARA[31] software.

2.7. NMR measurements with living cells

NMR experiments for studying integrin-RGDechi15D interactions within a cellular environment were acquired in the presence of HeLa and HepG2 living cancer cells. In order to avoid the internalization of the peptide all measurements in the presence and absence of cells were performed at 278 K. NMR cell samples were prepared dissolving 0.5 mg of RGDechi15D or RGDechiLinear in 200 μL of Hank’s balanced (HBSS) buffer pH 7.4 and 10% 2H2O containing 1x107 cells/ mL (HeLa or HepG2). In both cellular environments 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY spectra were carried out using 16 scans per t1 increment, a spectral width (SW) of 7201.56 Hz along both dimensions, a 1.0 s relaxation delay and 2048 × 128 complex points in t2 and t1, respectively. The 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY spectrum was measured using a homonuclear Hartmann-Hahn transfer through a MLEV17 sequence using a mixing time of 70 ms and 10 KHz spin-lock field strength. The 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY spectra were apodized with a square cosine window function and zero fill to a matrix of size 4096 × 1024 before Fourier transform and baseline correction. The bi-dimensional NOESY spectra were acquired using Uniform (US) and Non Uniform Sampling (NUS) (50% random sampling). The spectral width along both direct and indirect dimensions was 7201.56 Hz. The 2D [1H–1H] NOESY spectra were acquired by using a mixing time of 250 ms and 64 number of scans (32 for the uniform sampling version). The number of complex points was 2048 and 100 (50% NUS) for direct and indirect dimension, respectively. NUS data were reconstructed using two different protocols: IST (Iterative Soft Threshold) and IRLS (Iterative Reweighted Least Squares) [32] implemented in Bruker Topspin 4.0.1. The reconstructed NUS data were then processed with NMRPipe [29]. NUS data were zero-filled to a matrix of size 2048 × 2048.

T1ρ NMR experiments were measured for the RGDechi15D peptide before (free form) and after addition of HeLa and HepG2 living cancer cells. All spectra were recorded with a spectral width of 7201.56 Hz and 28 844 data points. For each sample a couple of spectra were measured by changing the duration of the T1ρ spinlock from 10 ms (reference spectrum) to 400 ms. A total number of 512 scans were recorded reaching a measurement time of 22 min and 25 min for the shorter (10 ms) and longer (400 ms) spinlock time, respectively. All T1ρ NMR experiments were acquired by using a Rf field strength for the T1ρ spinlock of 7000 Hz.

1H Saturated Transfer Difference (STD) experiments were acquired on the NMR cell samples with 3 000 and 1 000 scans for the long and short version, respectively. STD spectra were acquired with on-resonance irradiation at 0.2 ppm to selectively saturate (total saturation time of 2 s) protein resonances and off-resonance irradiation at 30 ppm for reference spectra by using the standard Bruker pulse sequence. STD spectra were acquired with a spectral width of 7201.56 Hz, 1.0 relaxation delay, 16 k acquisition points for acquisition

All T1ρ and STD NMR spectra were processed and analyzed using MestRe Nova (Mnova) software (Mestrelab Research S.L., Santiago de Compostela, Spain).

2.8. Chemical shifts evaluation and T1ρ data elaboration

1H,13C and 15N chemical shifts at 298 K were calibrated indirectly by external DSS reference.

Secondary chemical shifts for Cα, Hα, HN and Cβ were calculated by using as random coil shifts the values defined by Kjaergaard et al.[33], De Simone et al.[34] and Tamiola et al.[35]. The statistical probability of a trans or cis Xaa-Pro peptide bond was obtained by Promega[36] software using the following information: amino acid sequence of the peptide, proline chemical shifts and backbone chemical shifts of neighbouring residues. The per-residue model-free order parameters (S2) for the backbone amide groups were predicted from the backbone and Cβ chemical shifts using the Random Coil Index approach[37], [38]. The structural rearrangements of RGDechi15D induced by mutation were estimated by applying combined 1H (ΔδH), 15N (ΔδN) and 13C (ΔδC) Chemical Shift Perturbations (CSPs) based on the equation reported below:

Δ(H,N,C) = ((ΔδHWH)2 + ((ΔδNWN)2 + ((ΔδCWC)2)1/2

in which WH, WN and WC are weighing factor for 1H, 15N and 13C shifts defined as WH=|γH/ γH|=1; WN=|γN/ γH|=0.101 and WC=|γC/ γH|=0.251. ΔδH, ΔδN and ΔδC are the chemical shift differences in ppm between the compared peptide state for 1H, 15N and 13C, respectively; γH, γN and γC are the gyromagnetic ratios. The chemical shifts for the wild-type RGDechi peptide were obtained from a previous publication[23]. For the on-cell NMR characterization the chemical shifts evaluation was performed by using 1H shifts observed for the RGDechi15D peptide in the absence and in the presence of HeLa and HepG2 living cancer cells at 278 K.

The T1ρ attenuation factor (T1ρAF) for each well resolved resonance of RGDechi15D peptide in the free form and upon addition of HeLa and HepG2 living cells were calculated by evaluating the reduction of the height of 1H NMR signals in the two T1ρ experiments acquired with short (10 ms) and long (400 ms) spin-lock pulse. The intensity ratios were calculated for the peptide with and without living cells in according to the following equations:

| T1ρ-AFfree (%) = (I0free – Ifree)/I0free × 100 |

| T1ρ-AFcells (%) = (I0cells – Icells)/I0cells × 100 |

in which for the free RGDechi15D peptide, I0free defines the peak intensity in the reference (10 ms) spectrum and Ifree the peak intensity in the spectrum acquired with a longer spin-lock time (400 ms); whereas for the peptide in the presence of cells I0cells defines the peak intensity in the reference (10 ms) spectrum and Icells the peak intensity in the spectrum acquire with a longer spin-lock time (400 ms). Successively, the T1ρ ligand epitope mapping was obtained by defining the T1ρ binding effect (T1ρ-BE) according to the formula:

| T1ρ-BE (%) = T1ρ-AFcells - T1ρ-AFfree |

Only well-resolved resonances were considered in the analysis.

2.9. Molecular dynamics simulations

RGDechi15D peptide parameters were obtained using the Antechamber suite[39] and visually inspected and refined by the Leap module. MD simulation package Amber v18[40] was used to perform computer simulations by applying the Amber-ff14SB force field[41]. RGDechi15D peptide was centered in a triclinic box and solvated by a 10 Å shell (1896 molecules) of explicit TIP3P water[42] and one counter ion (Na + ) was added to neutralize the system. After energy minimization by the steepest descent method followed by a 1 ns equilibration phase where heavy atoms were position restrained by a harmonic potential, unrestrained systems were simulated in a NPT ensemble using the Langevin equilibration scheme to keep constant temperature (278 K, 298 K) and pressure (1 atm). Electrostatic forces were evaluated by the Particle Mesh Ewald method[43] and Lennard-Jones forces by a cutoff of 10 Å. All bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm[44]. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed in all three dimensions and the time step was set to 2 fs. Production runs of 10 ns were obtained at constant temperature of 278 K and 298 K, respectively, and structures were recorded every 2500 steps (5 ps) collecting a total of 2000 snapshots along the simulation time. Moreover, to enhance conformational sampling of RGDechi15D peptide mimicking experimental conditions, we run five independent replicas of 10 ns each at 278 K with different initial velocities. The obtained conformational ensemble was clustered using the protocol defined by Kelley et al.[45] generating 421 structural families. Successively, the representative cluster structures were analyzed by using experimental chemical shifts. In this case the chemical shifts were predicted from each representative structure by using the software PPM_ONE[46]. The representative structure was selected in according with the Global RMSD (experimental vs back-calculated) of Cα, Cβ, HN, Hα, N, Hside-chain chemical shifts, All selected MD models were visualized and analyzed using the programs PyMOL[47], CHIMERA[48] and PROCHECK-NMR[49].

2.10. Homology modeling

The three-dimensional model of the αvβ5-integrin was obtained through a two-steps structural modeling. First, the 3D model of the β5-subunit was predicted on the basis of their amino acid sequence by using two different approaches implemented in the I-TASSER[50] and ROBETTA[51] software. In particular, by using I-TASSER algorithm five models were predicted with C-scores ranging from −2.77 to 0.38. The C-score is a confidence score for estimating the quality of the predicted model and ranges from −5 to 2, with higher score representing higher confident in the model. Instead, by using ROBETTA five models were produced and the representative structure was selected by analyzing the Ramachandran plot obtained for each conformer by PROCHECK-NMR[49]. Considering the high structural similarity between the two models obtained by the two different approaches, the 3D structure predicted for the β5-subunit by ROBETTA was selected as reference 3D structural model on the bases of the structure quality factors. In particular, the Ramachandran plot analysis indicates that the ROBETTA structure is of a better quality than the model predicted by I-TASSER with over 98% residues in most favoured and additional allowed regions.

Second, to build the 3D structure of αvβ5-integrin we used as template the X-ray structure of the αvβ3 in complex with cyclo(-RGDf[NMe]V), “cilencitide (PDB code: 1L5G)[52], [53]. The obtained model for the αvβ5-integrin was refined using energy minimization/geometry optimization and was used as reference conformation in the Molecular docking studies.

2.11. Molecular docking

All docking processes were performed using AutoDock 4.0 program[54]. The molecular docking calculation involved the following steps: 1) preparing starting coordinate files for the ligand and the receptor in order to include in the protocol the information needed (spatial charges, polar hydrogen atoms, atom types and torsional degrees of freedom). For the RGDechi15D peptide we used as representative structure the conformation selected from the MD clusters by using NMR chemical shifts. In particular, we defined as starting structure the model proving the best description of the experimental chemical shifts. Instead, for the αvβ5 integrin we used the structure obtained, as reported in the previous paragraph, by structural modeling. Polar hydrogen atoms were added to the reference structures and the RGDechi15D rotatable bonds were automatically selected. 2) AutoGrid routine: the software AutoDock requires pre-calculated grid maps that are define by AutoGrid. The grid map consists of a 3D lattice of regularly spaced points, entirely or partly surrounding and centered on a specific region of the receptor (αvβ5 integrin). In our docking protocol, the grid size was set to be 70 × 70 × 70 and the grid space was 0.375 Å. 3) Docking procedure by AutoDock routine: a docking file, containing the input parameters for the docking calculation, was created by using the AutoDockTools. In details, we used as searching method the Lamarckian Generic Algorithm (LGA). Minimized ligands were randomly positioned inside the grid box and the docking process initiated with a quaternion and torsion steps of 58 torsional degrees of freedom, number of energy evaluations of 25 000 000 and run number of 100. After docking simulation, the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 structures were clustered by using a backbone RMSD cutoff of 2 Å. Moreover, the complex conformations were further evaluated against the experimental NMR data obtained by CSP, trNOESY and T1ρ analysis. The structures were analyzed and visualized by PyMoL[47] and Chimera[48]

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural characterization of the free RGDechi15D peptide

To gain insight into the structural features driving the receptor-peptide recognition mechanism between the RGDechi15D and αvβ5 integrin, we firstly investigated the peptide in the free form by natural-abundance NMR spectroscopy. A nearly complete assignment of 1H, 13C, and 15N resonances at 298 K (Tables SI1,SI2) has been obtained using the previously[23] reported strategy, in which, by exploring the natural isotopic abundance, homonuclear 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY (Figure SI1A), 2D [1H–1H] ROESY (Figure SI1), heteronuclear 2D [1H-15N] HSQC and [1H–13C] HSQC spectra were simultaneously analysed. Then, to deeply describe the conformational properties of the RGDechi15D, we examined the backbone chemical shifts (CSs) that are sensitive probe of protein/peptide secondary structure. In particular, to identify the secondary structure elements we analysed the Hα, Cα, HN secondary chemical shifts (Fig. 1 A,B,C) obtained as a difference between the observed chemical shift (δobs) and the residue specific random coil value (δobs). This latter value was estimated for the RGDechi15D peptide by using three different methodologies, as defined by Kjaergaard et al.[33], De Simone et al.[34] Tamiola et al.[35], respectively. Additionally, we also calculated the differences between Cα and Cβ secondary shifts (ΔδCα-ΔδCβ) (Fig. 1D), that represents a common procedure of reporting secondary chemical shifts. Independently of the random coil data set used, for the residues located in the RGD cycle (Lys1, Arg2, Gly3, Asp4 and DGlu5) Hα and Cα significantly deviate from the random coil chemical shifts with the Δδ values alternating from positive to negative along the cycle. Differently, for the residues located in the region comprising from Met6 to Thr19, Hα, Cα and HN chemical shifts only slightly deviate from the random coil, suggesting that in the this region the peptide does not adopt any preferential conformation. These structural findings were further confirmed by the analysis of the ΔδCα-ΔδCβ values that for whole peptide sequence are within ± 2 ppm range (Fig. 1D). We also explored the information obtained by the two-dimensional NOESY and ROESY experiments, providing an upper limit (ca. 5 Å) on the distance between protons that produce cross peaks. In our experimental conditions, no intra-molecular NOE connectivities were detected in the NOESY spectrum, while only intra-residue and short range ROEs were observed in the 2D-ROESY spectrum (Fig. 1E and Figures SI1B,SI2A). These results can be explained in terms of RGDechi15D dynamics, which modulate the evolution and the sign of the NOE. In details, a strong ROE cross peaks between the HN Lys1 and Hα DGlu5 indicate their proximity (Fig. 1E); for the residue pairs Asp8/Pro9, Asn12/Pro13 and Gly16/Pro17, relative strong ROE cross-peaks between the Hα of the previous residue and one or both of the prolyl Hδ2 and Hδ3 indicate that for the three proline residues (Pro9, Pro13 and Pro17) (Figure SI2A) the Xaa-Pro peptide bonds are principally in trans configuration (Figure SI2B). These latter results were further confirmed by analysing the Cβ and Cγ chemical shifts of the proline residues. As reported in the Table SI3, the difference Δβγ of ~ 5 ppm indicates, confirming the ROE connectivities, that all three proline residues present a trans Xaa-Pro peptide bond configuration. In addition, the chemical shifts analysis, performed by Promega[36], demonstrates the Xaa-Pro peptide bond is mainly in trans configuration with a probability of more than 90% (Table SI3). To fully address this finding, we estimated the population of the Xaa-Pro peptide bonds by analysing in the 2D [1H–13C] HSQC spectrum the resonances related to the cis and trans forms (Figure SI2C). The intensity analysis of the Cβ and Cγ NMR signals, in agreement with the results reported above, shows that all Xaa-Pro peptide bonds present an average cis population less than 10%. Overall, in agreement with the chemical shifts analysis, the inspection of the 2D-ROESY spectrum (Figure SI1B), as well as 3JHNHα coupling constants (Table SI4), indicate that the peptide adopts an unstructured conformation lacking ordered secondary structure elements as α-helix and β-strand. Interestingly, as indicated by the proton NMR chemical shifts temperature coefficients (ΔδHN/ΔT) (Table SI4), despite the high structural heterogeneity, the conformational space sampled by the RGDechi15D is locally restricted by weak hydrogen bonding or a mixture of hydrogen-bonded and solvent-exposed amide protons in the region flanking the Arg11(ΔδHN/ΔT = -4.00 ppb/K) and DGlu5 (ΔδHN/ΔT = -3.90 ppb/K).

Fig. 1.

Conformational characterization of RGDechi15D in the free form. Secondary chemical shifts of Hα (A), Cα (B), HN (C) plotted versus the residue numbers. The per-residue difference between Cα and Cβ (ΔδCα-ΔδCβ) secondary chemical shifts is also reported (D). The chemical shifts analysis was performed, as reported in the materials and methods, by using the random coil values defined by Kjaergaard at al., De Simone at al. and Tamiola at al., respectively. (E) ROEs mapping on the RGDechi15D primary sequence. Sequential- (R = 1) and medium-range (R less than 5) connectivities are reported as light blue and blue lines, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. RGDechi15D backbone dynamics

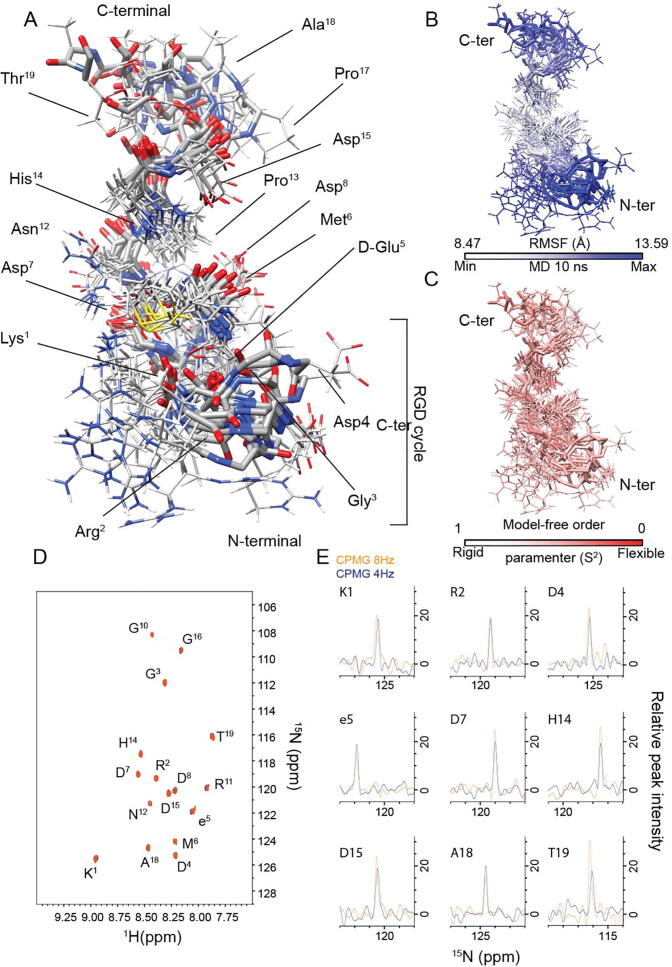

To describe the RGDechi15D conformational motions, we explored 15N backbone dynamics on the picosecond (ps) to millisecond (ms) timescale of the peptide by natural-abundance NMR techniques, and we probed the nanosecond conformational flexibility of the peptide, by using MD simulations. In fact, this latter technique provides a detailed picture of the dynamics process occurring in peptides/proteins on different timescales, and thus represents a valuable tool that is complementary to the experimental data obtained by NMR spectroscopy[55], [56], [57]. First, we generated, as reported in the materials and methods section, the conformational ensemble reproducing the ns RGDechi15D intrinsic motions (Fig. 2A). Then, we investigated the conformational dynamics of the peptide by calculating the per-residue backbone atoms root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) (Fig. 2B) from the generated 10 ns MD ensemble. The analysis of the RMSF values of RGDechi15D shows that the N-terminal region, containing the RGD cycle, exhibits a less conformational mobility than the C-terminal tail (Gly16-Thr19) in the ns timescale. Successively, we combined the dynamics information contained in the backbone chemical shifts (Fig. 2C) with the data obtained by measuring a couple of filtered [1H-15N] HSQC spectra, using two different relaxation-compensated CPMG periods (125 and 250 ms) (Fig. 2D, E). In this T2-filter HSQC experiment only the 1H-15N peaks of the residues, for which the 15N transversal relaxation time (T2) is longer than the applied filter, are detectable. As reported in the Fig. 2D, E, both T2-filter HSQC experiments acquired with the two filter delays report the 16 expected 1H-15N cross-peaks for the RGDechi15D peptide, indicating that all the residues are characterized by a 15N R2 (1/T2) auto-relaxation rate constant slower than 4 s−1. Therefore, the T2-filter HSQC data clearly indicate that the RGDechi15D presents, in the µs-to-ms time scale, a remarkable conformational flexibility with the RGD cycle resulting to be slightly more rigid than the C-terminal. Then, to provide a complete picture of the backbone dynamics of the RGDechi15D, we investigated the internal flexibility on the ps time scale by estimating the model-free order parameter (S2) for the backbone amide groups (Fig. 2C), which reports the amplitude of 15NH vector motions. S2 values reported in the Table SI4 indicate that the residues located in the cycle region (Lys1, Arg2, Gly3, Asp4 and D-Glu5) (S2avg = 0.65 ± 0.02) are characterized by a lower degree of flexibility than the C-terminal tail from Met6 to Thr19 (S2avg = 0.50 ± 0.09) in the ps time scale. Notably, these findings are in excellent agreement with the description of the ns conformational mobility obtained by 10 ns MD simulation.

Fig. 2.

RGDechi15D dynamics as revealed by NMR and MD. (A) RGDechi15D conformational ensemble obtained after clustering analysis of the 10 ns molecular dynamics simulation trajectories. The ensemble reports the representative structure of the 10 most populated clusters. RGDechi15D backbone is shown as stick model; whereas side-chains are reported as thin sticks. (B) Mapping of backbone Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) (Å) values onto a representative MD (10 ns) conformational ensemble. (C) Mapping of H-N model-free order parameters (S2) predicted, as reported in the materials and methods, from backbone and Cβ chemical shifts. (D) Overlay of the filtered 1H-15N HSQC spectra of RGDechi15D acquired using a relaxation-compensated CPMG period of 125 ms (8 s-1) (orange) and 250 ms (4 s-1), respectively. (E) Extracted 1D slices of 2D T2-filter 1H-15N HSQC NMR data of select backbone amide groups. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Overall, the RGDechi15D structural and dynamical characterization demonstrates that the peptide, lacking well-defined secondary structure elements, presents elevate conformational heterogeneity, with the C-terminal region showing higher degree of flexibility than the RGD cycle in both ns-to-ps and µs-to-ms time scales.

3.3. Structural comparison of the RGDechi15D mutant versus RGDechi

To describe the structural rearrangements induced by the mutation of the h-Cit15 to Asp, we compared the backbone (1H, 13C and 15N) chemical shifts assigned for the RGDechi15D mutant with those reported for the RGDechi in a previous publication[23]. Insertion of the Asp15 results in significant changes in the [1H-15N] HSQC and [1H–13C] HSQC correlation spectra (Fig. 3A). Larger chemical shift perturbations (ΔH,N,C) were observed for Lys1, Asp4, Asp8 and His14; whereas significant small differences were observed for Asp7, Arg11 and Thr19 (Fig. 3B upper). Notably, residues located inside the RGD cycle that are far beyond the mutation site show substantial structural variations, indicating that the RGDechi15D is characterized by long-range conformational rearrangements induced by mutation (Fig. 3B lower). These findings were further confirmed by comparison of 3JHNHα coupling constants (Fig. 3C left) and amide proton coefficients (ΔδHN/ΔT) (Fig. 3C middle) observed for the RGDechi15D with those previously published for the RGDechi peptide[23]. In particular, 3JHNHα coupling constants analysis indicates that the main differences in terms of torsion angles φ and ψ, induced by the mutation, are principally localized in the region flanking the mutation site. On the other hand, the amide NMR chemical shift temperature coefficients indicate that the long-range structural changes induced by the mutation are correlated to the loss of the hydrogen bond between the amide proton of the Lys1 and the side-chain carbonyl oxygen of the D-Glu5. As indicated by the comparison of the model-free order parameter S2 (Fig. 3C right), these structural findings are also associated with the higher conformational flexibility observed for the residues of the RGD cycle upon mutation. Overall, data show that the RGDechi peptide upon mutation undergoes significant structural rearrangements coupled with an increase in conformational flexibility in the region containing the RGD cycle.

Fig. 3.

Structural and dynamics effects of hCit15D mutation. (A) Selected region of the assigned 1H-15N HSQC (Upper) and 1H–13C HSQC (Lower) spectra of RGDechi15D (blue) and RGDechi (red) peptide acquired, by exploring natural isotopic abundance, on a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer at 298 K. (B) Upper Plot of combined 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shifts perturbation (CSP ΔH,N,C) as a function of the residue numbers. Lower Mapping of the CSP values onto the structural model of the RGDechi15D mutant. Residues with weighted 1H, 13C and 15N CSP higher than the average CSPavg and CSPavg + SD are shown in light blue and blue, respectively. The side-chain of the residue Asp15 is depicted in yellow. (C) Correlation plots of 3JHNHα (left), ΔδNH/ΔT (center) and H-N order-parameter (S2) (right) NMR parameters measured for RGDechi15D with respect to those observed for the RGDechi peptide. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4. Development of the NUS/T1ρ-NMR based methodology

To get structural insights into the binding of RGDechi15D to αvβ5 integrin within a cellular environment we performed a high-resolution NMR investigation of receptor-peptide interactions with living cancer cells. To this aim, we first selected two cell lines, HeLa and HepG2, with different histological origin and morphology, but showing the same αvβ5 and αvβ3 integrin expression level. In details, both HeLa and HepG2 cell lines showed 1.7 ± 0.1 × 104 αvβ5 integrin and undetectable amounts of αvβ3, estimated by quantitative flow cytometry, as previously reported[5], [24]. In our strategy, HeLa cells were firstly used to get NMR data for building a model of the RGDechi15D/ αvβ5 complex, whereas HepG2 cells were later used as positive control in the validation procedure (see next paragraph). Additionally, to inhibit the peptide internalization in both cell lines, the NMR structural investigation was performed at low temperature (278 K).

First, we assigned the 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts of RGDechi15D at 278 K by inspection of 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY, 2D [1H–1H] ROESY and natural abundance NMR experiments as [1H-15N] HSQC and [1H–13C] HSQC experiments (Table SI5,6). Then, to explore the RGDechi15D binding to αvβ5 integrin with living HeLa cells, we applied the conventional strategy in which the chemical shift assignments at 278 K (Table SI7) was performed by 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY spectrum; whereas STD and trNOESY experiments were analysed to describe the structural determinants governing the recognition mechanism of αvβ5 integrin by RGDechi15D-formation.

With this method, to acquire whole set of NMR spectra with a reasonable S/N ratio and resolution a total experimental time of 16 h was required. In order to verify the impact of NMR analysis on cell viability, we performed Trypan Blue exclusion test before and after the NMR measurements. Trypan blue is a dye used to distinguish between live and dead cells. In particular, it is not absorbed by viable cells, but stains cells with a damaged cell membrane so that under light microscopy only death cells have a blue color. Then, cells were plated and observed for 24 h. As reported in the Fig. 4A the HeLa cells viability after 16 h in the NMR tube was reduced of more than 25%; however, when observed 24 h after plating, only few cells attached the plate surface forming cells cluster. These data suggest that, even if the 75% of cells have intact membrane-Trypan blue is excluded- cell homeostasis and functionality of the alive cells was seriously compromised.

Fig. 4.

Mapping of the binding interface between RGDechi15D and αvβ5 integrin on living HeLa cancer cells surface. (A) HeLa TB exclusion tests of the cell samples before and after 3 and 16 h NMR measurements; high power micrographs of HeLa cells plated after NMR experiments at 5X (scale bar 200 µm) and 10X (scale bar 100 µm) magnification (B) Overlay of the 1H spectrum of RGDechi15D acquired before adding HeLa cells (blue) with that of the supernatant of the cell sample collected after NMR measurements (red). (C) Chemical shifts perturbations of RGDechi15D 1H resonances (ppm) upon addition of HeLa living cells. The dark grey line indicates the average chemical shift perturbation value (CSPavg) and the dark grey dashed line reports the CSPavg + SD. (D) Comparison of the 2D NUS [1H,1H] tr-NOESY spectrum of RGDechi15D acquired upon addition of HeLa intact cells with the 2D US [1H,1H] ROESY measured in solution (blue) and (teal) . The intermolecular trNOEs are indicated as orange box. (E) Binding epitope map defined by comparison the T1ρ-NMR experiments of RGDechiD15 acquired without and with HeLa cells. RGDechi15D protons with T1ρ-BE (x) upon addition of living cells x greater than 15% and 10 ≤ x ≤ 15% are reported as full and half circles, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Previous studies also reported that the lifetime of HeLa cells inside the NMR tube was 85–90% after 3 h[58], [59]. Then, in order to acquire the complete NMR data set within 3 h on the same in-cell NMR sample we tried to shorten the duration of the NMR experiments by reducing the number of scans (NS) of the 2D US [1H–1H] trNOESY and the STD experiments (Figure SI3) (total duration = 5 h and 35 min). Unfortunately, this optimization procedure failed because the reduction of number of scans drastically decrease of the Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) of the NMR spectra with several peaks around or barely above the noise level (Figure SI3A,B). In particular, for the STD experiment the reduction of the NS from 3000 to 1000 produces a substantial lowering of the average SNR of about 50% (Figure SI3C).

Therefore, to overcome these limitations, we developed an alternative NMR-based strategy for investigating, at an atomic level, the molecular determinants driving the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex formation on living cells surface. In particular, taking advantage of the sensitivity enhancement of NMR-cryoprobe over room temperature probe, we combined NUS and T1ρ methodologies (Fig. 4) to reduce the duration of the NMR experiments and collect, within the HeLa cells lifetime, the whole data set required for an accurate structural investigation. On one hand, considering the short living time of the cell sample due to cells sedimentation and peptide internalization, the application of NUS methodology allowed us to speed up the acquisition of the 2D NUS [1H–1H] trNOESY spectra. In fact, NUS offers potential solution by collecting in the indirect dimension fewer increments than uniform sampling (US) and then reconstructing the full spectrum[32], [60], [61], [62], [63]. In this regard, it is possible to either decrease the overall experiment time or increase the SNR by using more NS. On the other hand, in order to further reduce the NMR acquisition time we used T1ρ relaxation based NMR experiments as alternative tool to the STD[19] technique which is characterized by low sensitivity and then, it requires long experimental times to collect spectra with an appropriate SNR. In this scenario, we developed and optimized a protocol based on the acquisition of a pair of T1ρ relaxation-based experiments acquired with a short (reference spectrum) and long spinlock pulse with and without living cells. In fact, for a peptide bound to a large target receptor located on the cell surface (i.e αvβ5 integrin MW 204 kDa), a long spinlock pulse produces significant line broadening of its resonances because the peptide adopts the enhanced transfer R1ρ relaxation rate of the receptor, and thus the intensity of the acquired spectrum will be reduced with respect to that observed in the absence of living cells. Therefore, after measuring T1ρ relaxation-based experiments, we defined the T1ρ Attenuation Factor (T1ρ-AF) by evaluating the difference between the peak intensities of the reference spectrum (acquired with a shorter spin-lock time of 10 ms) with those of the spectrum acquired with a longer spin-lock time (400 ms) for the RGDechi15D peptide without (T1ρ-AFfree) and with HeLa cells (T1ρ-AFcells), respectively. Successively, we delineated the T1ρ Binding Effect (T1ρ-BE) by subtracting the T1ρ-AF obtained for each well-resolved proton of RGDechi15D in the free form to the value calculated for the same resonance upon addition of living HeLa cells. Interestingly, the combination of NUS and T1ρ NMR techniques allowed the acquisition of the complete NMR data set (2 h and 46 min) within the HeLa cells lifetime (3 h), ensuring that only data of intact cells were acquired. This latter crucial aspect was further confirmed by evaluating the HeLa cell viability of the NMR sample. Indeed, the cells viability and plating data indicate that, after NMR measurements (~3 h), HeLa cells viability is intact (100%) and, more importantly, the alive cells kept their ability to attach plate surface and to assume their typical morphology suggesting that cell homeostasis is preserved (Fig. 4A) Notably, the comparison of the 1H NMR spectrum of RGDechi15D acquired in the absence of HeLa cells at the beginning of the NMR data set with that of the supernatant of the cells sample measured at the end of the experiments indicates that at 278 K the peptide internalization process was completely inhibited during the 3 h of NMR measurements (Fig. 4B).

3.5. Application of the NUS/T1ρ-NMR based strategy for defining the binding mode of RGDechi15D to αvβ5 integrin on living cells surface

In agreement with our approach we firstly collected the structural information of the RGDechi15D- binding epitope to αvβ5 by acquiring 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY, 2D NUS [1H–1H] trNOESY and T1ρ NMR experiments in the absence and in the presence of αvβ5 integrin expressing Hela cells at 278 K (Fig. 4C-E). Then, the obtained high-resolution structural data were used as conformational constraints to perform a series of Molecular Dynamics and Molecular Docking studies (see next paragraph).

To start, we analyzed the 1H chemical shift changes (Tables SI5 and SI7) for all protons (backbone and side chains) (ΔH) of RGDechi15D upon addition of HeLa living cancers cells. Interestingly, as illustrated in the Figure 4C, a subset of resonances the RGDechi15D showed significant changes in the presence of HeLa cells suggesting that the αvβ5-integrin binding process is modulated by several residues. In details, remarkable chemical shift perturbation (CSP > CSPavg + SD) was observed for the Asn12 located in the C-terminal region of the peptide; whereas significant smaller differences were observed for Lys1 and Asp4 located inside the RGD cycle and for Asp8, Pro9, Arg11, His14, Asp15 and Pro17 situated in the C-terminal region. Then, to determine the conformation that the RGDechi15D peptide adopts upon binding to αvβ5 integrin in HeLa living cells we exploited the structural information provided by the two-dimensional trNOESY experiments reordered using NUS acquisition mode (Fig. 4 D). A detailed analysis of 2D NUS [1H–1H] trNOESY spectra acquired in the presence of HeLa cells indicates that Lys1 and Arg2 as well as the Asp4, located inside the RGD cycle, showed either new or stronger cross-peaks. New tr-NOE correlations were also observed for Asp8, Asn12, His14 and Asp15 upon addition of HeLa cells (Fig. 4, SI4). Interestingly, strong NOE cross-peaks between Hα of the residue Asp8, Asn12 and Gly16 and the Hδ of Pro9, Pro13 and Pro17, respectively, indicate that the higher population of the Xaa-Pro trans-arrangement observed for the three prolines in the free RGDechi15D is preserved upon binding to the αvβ5 integrin on living cells surface. Successively, to further characterize the RGDechi15D-binding epitope to αvβ5 in the cellular environment, in accordance with our approach, we analysed a pair of T1ρ relaxation-based experiments acquired on the peptide in the presence and absence of HeLa cancer cells (Fig. 4E, SI3B). In particular, the RGDechi15D hydrogens that are closer to the αvβ5 receptor upon binding were identified by analysing T1ρ-AF and T1ρ-BE parameters obtained as reported above (see also the materials and methods). We classified the T1ρ-BE for HeLa living cells as medium (10% ≤ T1ρ-BE ≤ 15%) and strong (T1ρ-BE greater than 15%) depending on the reduction of the RGDechi15D signal intensities upon interaction to the αvβ5 integrin.. In details, in the amide proton region, strong T1ρ-BE was observed for Gly3 located inside the RGD cycle, whereas medium effects were observed for Asp4, Asp7, Asn12, Asp15 backbone amides and for His14 side-chain protons (Fig. 4E). In the aliphatic region, strong T1ρ-BE were ascribed to Hβ2/Hβ3 Asp4, Hβ2/Hβ3 Pro9, Hβ2/Hβ3 Asn12 (only in the case HeLa cells), Hα and Hβ2/Hβ3 Asp15 and Hβ2/Hβ3 Pro17. A medium T1ρBE was observed for Hβ2/Hβ3 and Hδ Lys1, Hα Arg2 and Hα Gly3 situated within the RGD cycle, for Hβ Asp8, Hα (only in the case of HeLa cells) and Hδ Pro9, Hδ and Hε Arg11, Hβ Asn12 (only in the case HepG2 cells), Hε2 His14, Hα and Hβ Asp15, Hβ Prp17. Overall, trNOESY and T1ρ data, in agreement with the chemical shift perturbations analysis, indicate that the binding mechanism of αvβ5 integrin by RGDechi15D is principally mediated by Lys1, Arg2 and Gly3 located inside the RGD cycle. Moreover, the NMR structural data clearly demonstrate that the formation of the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex is further stabilized by additional residues (Arg11-Thr19) of the C-terminal echistatin moiety.

3.6. Validation of the NUS/T1ρ-NMR methodology

Since in our approach the structural information collected by the combination of NUS and T1ρ techniques are essential for providing an high-resolution description of protein-peptide interactions with living cells, we validated the integrated NMR strategy utilizing a proper positive and negative control. As positive control, we used the HepG2 cells that, as already mentioned, share with the HeLa cells the same αvβ5/αvβ3 integrin pattern. In the presence of HepG2 cells RGDechi15D shows chemical shifts variations (Figure SI4A, Table SI8), as well as tr-NOE correlations and T1ρ-BE values (Fig. SI4B,C), similar to those observed upon addition of the HeLa cells demonstrating that the αvβ5-integrin binding interaction occurs with a similar recognition mechanism.

As negative control, we used a linear RGDechi peptide (named RGDechilinear) lacking the RGD cyclic motif. At first we tested the ability of the linear peptide to bind αvβ5-integrin by apoptosis and invasion assay experiments (Figure SI5). In detail, after treating HepG2 with 50 µM linear peptide for 6 h, as shown in the Figure SI5A, RGDechilinear does not induce apoptosis, differently RGDechi15D induces a remarkable increase in caspase activity as described in Capasso et al.[24]. Moreover, as previously demonstrated[24], RGDechi15D peptide shows significant decrease in tumor cell invasiveness with respect to untreated cells (control), differently linear peptide does not affect HepG2 invasion (Figure SI5B). Data were quantified in the graph (Figure SI5C). Therefore, we tested the efficacy of the NUS/T1ρ-NMR methodology by applying this combined strategy to the living cell sample containing the linear peptide (Figure SI6A-E). As reported in the figure SI6D, the 2D NUS [1H–1H] trNOESY acquired for the linear RGDechi peptide upon addition of the living cells does not show any new inter-molecule NOE correlations indicating, in agreement with the chemical shifts analysis (Figure SI6B-C, Table SI9,10), that the peptide does not bind the integrin. These findings were further confirmed by the structural information obtained using the T1ρ experiments. As illustrated in the figure SI6E, the T1ρ-BE values, calculated for the well resolved proton resonances of RGDechilinear, indicates that the presence of cells having the αvβ5-integrin on the membrane surface does not significantly reduce the NMR signal intensities demonstrating that RGDechilinear retains the same conformational features observed in solution. Overall, in according with apoptosis and invasion assay results, the structural data here obtained demonstrate that the linear peptide RGDechilinear does not interact with the αvβ5 integrin highlighting the crucial role of the RGD cyclic motif in the αvβ5 recognition mechanism.

3.7. Molecular docking studies of RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex

To provide a more rigorous description of the molecular determinants driving the αvβ5 binding mechanism by RGDechi15D, we performed a series of Molecular Docking studies by including in the docking protocol the structural dynamics information collected through NMR methods (i.e. Secondary Chemical shifts analysis, CSPs, trNOESY and T1ρ) and Molecular Dynamics simulations for RGDechi15D in the free and bound forms. Therefore, in order to consider the RGDechi15D conformational flexibility and include this piece of information in the Molecular Docking of RGDechi15D/αvβ5 interaction, we performed a series of Molecular Dynamics simulations at 278 K of 10 ns each, collecting up to 50 ns of simulation time. Then, we analysed the ensemble (5 × 1000 conformers) (Figure SI7A) obtained from 50 ns MD simulation through cluster analysis and by using the experimental chemical shifts observed for the peptide at 278 K. In particular, we used the PPM approach[46] as chemical shifts prediction tool to back-calculate the backbone and side-chains CSs from the representative conformations of each cluster. Then, we compared the observed chemical shifts with those predicted for each single representative structure. As reflected by the RMSD values (Figure SI7B), this CSs-based selection procedure allowed the identification of the RGDechi15D conformer that provides a reasonable description of the experimental CSs NMR data (Global RMSD = 4.55 ppm) . Subsequently, we used this selected structural model as reference structure for the RGDechi15D peptide in the docking protocol (see below). For the αvβ5 receptor, since the high-resolution 3D structure is not yet available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), we built a three-dimensional model by using a multi-step homology modelling process based on the crystal structure of αvβ3 integrin in complex with cyclo(-RGDf[NMe]V, “cilengitide” (PDB code: 1L5G)[52], [53]. In fact, since αvβ5 and αvβ3 show high percentage of sequence identity at the α and β interface and bind common small compounds, it has been plausible to assume that in the αvβ5-bound conformation the two subunits assemble in a similar manner as observed in αvβ3. First, we computationally predicted the 3D structure of the β5 subunit from the amino-acid sequence by using two different approaches implemented in ROBETTA[51] and I-TASSER[50] software. Interestingly, as reflected by the RMSD values (Figure SI8A-D), the two approaches predicted a very similar structural organization for the region (Ser84-Thr400) of the β5 subunit involved in the recognition of the RGD motif (Figure SI8 C-D). Although the structural similarities the Ramachandran plot statistics indicate that the 3D model predicted by ROBETTA is of a better quality than I-TASSER model with over 98% residues in most favoured and additional allowed regions (Table SI11 Figure SI8A,B). Second, we assembled the β5 subunit 3D model predicted by ROBETTA with the αv subunit using as structural template the αvβ3/cilengitide complex. Third, the generated 3D model of the αvβ3 integrin was energetically minimized, as reported in the materials and methods section, and it was used as reference structure for the receptor in the docking studies (Figure SI8E).

As a result, the molecular docking calculations generated 100 solutions and were subsequently sorted into clusters using a backbone RMSD cutoff of 2 Å. This procedure resulted in three most populated clusters (Cluster1, Cluster2 and Cluster3) characterized by substantial structural differences in the binding modality to αvβ5 integrin by RGDechi15D peptide (Figure SI9A). Since the first cluster better agrees with the structural NMR data (Figure SI9B), we selected the representative model of this cluster as reference structure of the RGDechiD15/αvβ5 complex.

3.8. RGDechi15D -αvβ5 recognition mechanism

The selected structural model of the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex, as derived by experimental and computational data, is shown in Fig. 5. The RGDechi15D binding epitope is constituted by a rather extended surface defined by Lys1, Arg2, Gly3, Asp4 located inside the RGD cycle and by Pro9, Arg11, Asn12, Pro13, His14, Asp15 and Pro17 of the C-terminal echistatin moiety (Table SI12). Notably, all residues of the RGDechi15D peptide involved in the interaction with αvβ5 show T1ρ binding effect and intermolecular NOEs, upon addition of HeLa and HepG2 living cells. In details, the RGD-containing cycle mainly interacts with the β5 subunit (Fig. 5 A-C) (Table SI12); especially, Lys1 interacts by ionic interactions with β5-Arg241 and β5-Cys202 (Fig. 5A), Arg2 makes contact with several residues of the β5 subunit (Ser147, Leu148, Ser240, Pro231, Phe215) (Fig. 5A); Gly3 interacts with β5-Asn242 whereas Asp4 makes contact with β5- Ser149, β5- Asp278 and β5-Asp279 (Fig. 5A). Regarding the region preceding, the C-terminal echistatin moiety Asp8 and Pro9 mainly interact with αv-subunit (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the interaction between αvβ5 and RGDechi15D is further stabilized by residues of the C-terminal echistatin moiety (Arg11-Thr19), that contacts both αv and β5 subunits. In particular, Arg11 is involved in hydrogen bonds with αv-Asp150 (Fig. 5B); whereas Asn12 is hydrogen bonded with αv-Tyr178 (Fig. 5B,C). Pro13 interacts with Asp148, Ala149, Tyr178 of the αv-subunit (Fig. 5C); whereas the side-chain of His14 in involved in ionic interaction with αv-Asp148 (Fig. 5C). Finally, Asp15, Gly16 and Pro17 residues play a crucial role in the stabilization of the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex by selectively interacting with the β5-subunit (Fig. 5D). Notably, Asp15 Gly16 and Pro17 of RGDechi15D peptide exclusively interacts with residues located inside the specificity determining loop (SDL) (Figure SI10 and SI11A, B) that is extremely important for the natural ligand selectivity between αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins[64], [65]. This observation, together with the fact that, in the amino-acid sequence of the β3, the β5-Lys206 is replaced with an Asp residue (β3-Asp205) (Figure SI11B) clearly indicate that in RGDechi15D the Asp15 plays a crucial role in shifting the selectivity of the peptide from αvβ3 to αvβ5.

Fig. 5.

Structural model of the RGDechi15D-αvβ5 complex. A-D Close-view up of the representative model of the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex obtained by molecular docking and validated by using the experimental NMR data. Residues of αv and β5 subunits depicted in light blue and gold, respectively. The RGDechi15D peptide is reported in dark grey; whereas the side chains of the residues involved in the complex formation are depicted in light green. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Conclusions

Herein, we developed and applied an alternative methodology for studying receptor-ligand interactions with living cells at atomic resolution. Our application combines high-resolution structural and dynamics NMR data with Molecular Dynamics simulations and Molecular Docking studies. In particular, the methodology relies on the following steps (Fig. 6): i) after preparation of the sample containing living cells overexpressing the receptor and the unlabeled ligand (i.e peptide, protein, small compound) the chemical shifts assignment is achieved by the acquisition of the 2D [1H–1H] TOCSY spectrum (time ~ 43 min); ii) inspection of 2D NUS [1H–1H] trNOESY spectra to investigate the preferred conformation of bound ligand. NUS techniques allow to reduce the acquisition time (from 163 to 77 min using for both 64 number of scans) considering the short living time of the cells (3 h): iii) acquisition of a pair of T1ρ relaxation-based experiments instead of STD experiments to define the binding epitope. The acquisition time was significant reduced (from 335 to 46 min), obtaining the same essential structural details with increasing S/N ratio (more than 50%) and resolution of NMR spectra. Two novel parameters, T1ρ-AF (T1ρ Attenuation factor) and T1ρ-BE (T1ρ Binding Effect), were defined to get more quantitative conformational information from T1ρ NMR experiments; iv) description of the conformational space sampled by the ligand in solution by performing a series of Molecular Dynamics simulations; v) identification of the reference conformation for the ligand by analysing the MD ensemble with the experimental 1H, 15N and 13C chemical shifts; whereas for the receptor, if the high-resolution structure resolved by X-Ray, NMR or CryoEM, is not available, a series of molecular modelling calculations are required; vi) investigation of the structural determinants governing the receptor-ligand complex formation by performing molecular docking studies; vii) cluster analysis of the Molecular docking conformations and selection of the representative model of the receptor-ligand complex by using the experimental NMR data.

Fig. 6.

Flow chart of our approach for high resolution investigation of receptor-ligand interactions based onon-cell NMR structural data. The comparison of the NUS/ T1ρ methodology with the previous STD-based strategy with the strategy is also reported.

We tested the developed a methodology to investigate the structural details driving the formation of the RGDechi15D/αvβ5 complex. The results indicate that the recognition mechanism of αvβ5 integrin by RGDechi15D is principally mediated by the residues located inside the RGD cycle and it is further stabilized by additional residues (Arg11-Thr19) of the C-terminal echistatin moiety. Overall, the RGDechiD15-αvβ5 structural model provides a detailed description of the molecular determinants responsible for the peptide selectivity for αvβ5, demonstrating that the Asp15 residue plays an essential role in shifting the selectivity of the peptide from αvβ3 to αvβ5.

In conclusion, our developed methodology was successfully applied in the investigation of the direct binding of the RGDechi15D peptide with the αvβ5 integrin with living human cancer cells. This approach represents an alternative NMR tool for studying, at atomic resolution, receptor-ligand recognition mechanism on living cells surface and for screening of the interaction profiling of drugs with their therapeutic targets in their native cellular environment.

5. Author contributions

BF, AC, CA and LR acquired and analyzed the NMR data; ADG, DC and LZ synthetized the peptide; SDG, DC and MTG prepared the cell culture and monitored cell viability; LR conceived and supervised the project, designed the NMR experiments; AP performed Molecular Dynamics simulations; LR and CA Molecular docking calculations. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by “Programma Valere” 2018 of University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” to L.R. and by grants from Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, Programma Operativo Nazionale Ricerca e Competitivita’ 2007–2013 PON 01_01078 and PON 01_2388.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.05.047.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Uhlen M., Oksvold P., Fagerberg L., Lundberg E., Jonasson K., Forsberg M., et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(12):1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/nbt1210-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giri A.K., Ianevski A., Aittokallio T. Genome-wide off-targets of drugs: risks and opportunities. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2019;35(6):485–487. doi: 10.1007/s10565-019-09491-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin W.-H., Christoffer C.W., Kihara D. In silico structure-based approaches to discover protein-protein interaction-targeting drugs. Methods. 2017;131:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham B., Loh C.T., Swarbrick J.D., Ung P., Shin J., Yagi H., et al. DOTA-amide lanthanide tag for reliable generation of pseudocontact shifts in protein NMR spectra. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22(10):2118–2125. doi: 10.1021/bc200353c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diana D., Russomanno A., De Rosa L., Di Stasi R., Capasso D., Di Gaetano S., et al. Functional binding surface of a β-hairpin VEGF receptor targeting peptide determined by NMR spectroscopy in living cells. Chemistry. 2015;21(1):91–95. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbieri L., Luchinat E., Banci L. Characterization of proteins by in-cell NMR spectroscopy in cultured mammalian cells. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(6):1101–1111. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luchinat E., Banci L. A Unique Tool for Cellular Structural Biology: In-cell NMR. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(8):3776–3784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.643247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luchinat E, Banci L. In-cell NMR: a topical review. IUCrJ. 2017;4:108-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Mari S., Invernizzi C., Spitaleri A., Alberici L., Ghitti M., Bordignon C., et al. 2D TR-NOESY experiments interrogate and rank ligand-receptor interactions in living human cancer cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(6):1071–1074. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potenza D., Vasile F., Belvisi L., Civera M., Araldi E.M.V. STD and trNOESY NMR study of receptor-ligand interactions in living cancer cells. ChemBioChem. 2011;12(5):695–699. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claasen B., Axmann M., Meinecke R., Meyer B. Direct observation of ligand binding to membrane proteins in living cells by a saturation transfer double difference (STDD) NMR spectroscopy method shows a significantly higher affinity of integrin alpha(IIb)beta3 in native platelets than in liposomes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:916–919. doi: 10.1021/ja044434w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamidi H., Ivaska J. Every step of the way: integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(9):533–548. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieberler M., Reuning U., Reichart F., Notni J., Wester H.-J., Schwaiger M., et al. Exploring the Role of RGD-Recognizing Integrins in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2017;9(12):116. doi: 10.3390/cancers9090116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Gatto A., Zaccaro L., Grieco P., Novellino E., Zannetti A., Del Vecchio S., et al. Novel and selective alpha(v)beta3 receptor peptide antagonist: design, synthesis, and biological behavior. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3416–3420. doi: 10.1021/jm060233m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zannetti A., Del Vecchio S., Iommelli F., Del Gatto A., De Luca S., Zaccaro L., et al. Imaging of alpha(v)beta(3) expression by a bifunctional chimeric RGD peptide not cross-reacting with alpha(v)beta(5) Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5224–5233. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santulli G., Basilicata M., De Simone M., Del Giudice C., Anastasio A., Sorriento D., et al. Evaluation of the anti-angiogenic properties of the new selective αVβ3 integrin antagonist RGDechiHCit. J Transl Med. 2011;9(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pisano M., Paola D.E., Nieddu I., Sassu V., . I., Cossu, Galleri S., et al. In vitro activity of the αvβ3 integrin antagonist RGDechi-hCit on malignant melanoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:871–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capasso D., de Paola I., Liguoro A., Del Gatto A., Di Gaetano S., Guarnieri D., et al. RGDechi-hCit: αvβ3 selective pro-apoptotic peptide as potential carrier for drug delivery into melanoma metastatic cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e106441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farina B., de Paola I., Russo L., Capasso D., Liguoro A., Gatto A.D., et al. A Combined NMR and Computational Approach to Determine the RGDechi-hCit-αv β3 Integrin Recognition Mode in Isolated Cell Membranes. Chemistry. 2016;22(2):681–693. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comegna D., Zannetti A., Del Gatto A., de Paola I., Russo L., Di Gaetano S., et al. Chemical Modification for Proteolytic Stabilization of the Selective α. J Med Chem. 2017;60:9874–9884. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo L, Farina B, Del Gatto A, Comegna D, Di Gaetano S, Capasso D, et al. Deciphering RGDechi peptide‐α5β1 integrin interaction mode in isolated cell membranes. Peptide Science. 2018;110.

- 22.Hill B.S., Sarnella A., Capasso D., Comegna D., Del Gatto A., Gramanzini M., et al. Therapeutic Potential of a Novel α. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/cancers11020139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farina B., Del Gatto A., Comegna D., Di Gaetano S., Capasso D., Isernia C., et al. Conformational studies of RGDechi peptide by natural-abundance NMR spectroscopy. J Pept Sci. 2019;25(5):e3166. doi: 10.1002/psc.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capasso D, Del Gatto A, Comegna D, Russo L, Fattorusso R, Saviano M, et al. Selective Targeting of αvβ5 Integrin in HepG2 Cell Line by RGDechi15D Peptide. Molecules. 2020;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Capasso D., Di Gaetano S., Celentano V., Diana D., Festa L., Di Stasi R., et al. Unveiling a VEGF-mimetic peptide sequence in the IQGAP1 protein. Mol BioSyst. 2017;13(8):1619–1629. doi: 10.1039/c7mb00190h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brüschweiler R., Ernst R.R. Coherence transfer by isotropic mixing: Application to proton correlation spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1983;53:521–528. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar A., Ernst R.R., Wüthrich K. A two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser enhancement (2D NOE) experiment for the elucidation of complete proton-proton cross-relaxation networks in biological macromolecules. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;95(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90695-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griesinger C., Ernst R.R. Frequency Offset Effects and Their Elimination in NMR Rotating-Frame Cross-Relaxation Spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1987;75(2):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee W, Tonelli M, Markley JL. NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1325-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.R.L.J. K. Optimizing the process of nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum analysis and computer aided resonance assignment Dissertation, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich. 2004.

- 32.Kazimierczuk K., Orekhov V.Y. Accelerated NMR spectroscopy by using compressed sensing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(24):5556–5559. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kjaergaard M., Brander Søren, Poulsen F.M. Random coil chemical shift for intrinsically disordered proteins: effects of temperature and pH. J Biomol NMR. 2011;49(2):139–149. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9472-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Simone A., Cavalli A., Hsu S.-T., Vranken W., Vendruscolo M. Accurate random coil chemical shifts from an analysis of loop regions in native states of proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(45):16332–16333. doi: 10.1021/ja904937a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamiola K., Mulder F.A. Using NMR chemical shifts to calculate the propensity for structural order and disorder in proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:1014–1020. doi: 10.1042/BST20120171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen Y., Bax A. Prediction of Xaa-Pro peptide bond conformation from sequence and chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2010;46(3):199–204. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berjanskii M.V., Wishart D.S. A simple method to predict protein flexibility using secondary chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(43):14970–14971. doi: 10.1021/ja054842f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berjanskii M.V., Wishart D.S. The RCI server: rapid and accurate calculation of protein flexibility using chemical shifts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server):W531–W537. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(9):1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Case D.A., Cheatham T.E., Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K.M., et al. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K.E., Simmerling C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11(8):3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J.D., Impey R.W., Klein M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79(2):926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darden T.A., Pedersen L.G. Molecular modeling: an experimental tool. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(5):410–412. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elber R., Ruymgaart A.P., Hess B. SHAKE parallelization. Eur Phys J Spec Top. 2011;200(1):211–223. doi: 10.1140/epjst/e2011-01525-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelley L.A., Gardner S.P., Sutcliffe M.J. An automated approach for clustering an ensemble of NMR-derived protein structures into conformationally related subfamilies. Protein Eng. 1996;9(11):1063–1065. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.11.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li D.-W., Brüschweiler R. PPM: a side-chain and backbone chemical shift predictor for the assessment of protein conformational ensembles. J Biomol NMR. 2012;54(3):257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeLano W.L. San Carlos; CA, USA: 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (2002) DeLano Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laskowski R.A., Rullmannn J.A., MacArthur M.W., Kaptein R., Thornton J.M. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy A., Kucukural A., Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim D.E., Chivian D., Baker D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server):W526–W531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong J.P., Stehle T., Zhang R., Joachimiak A., Frech M., Goodman S.L., et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science. 2002;296:151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiong J.P., Stehle T., Diefenbach B., Zhang R., Dunker R., Scott D.L., et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3. Science. 2001;294:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.1064535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diana D., Ziaco B., Scarabelli G., Pedone C., Colombo G., D'Andrea L., et al. Structural analysis of a helical peptide unfolding pathway. Chemistry. 2010;16(18):5400–5407. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russo L., Raiola L., Campitiello M., Magrì A., Fattorusso R., Malgieri G., et al. Probing the residual structure in avian prion hexarepeats by CD, NMR and MD techniques. Molecules. 2013;18(9):11467–11484. doi: 10.3390/molecules180911467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russo L., Maestre-Martinez M., Wolff S., Becker S., Griesinger C. Interdomain dynamics explored by paramagnetic NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(45):17111–17120. doi: 10.1021/ja408143f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Inomata K., Ohno A., Tochio H., Isogai S., Tenno T., Nakase I., et al. High-resolution multi-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of proteins in human cells. Nature. 2009;458(7234):106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature07839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]