Key Points

Question

Is the preventive migraine treatment intravenous eptinezumab effective when initiated during a migraine attack?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial included 480 patients eligible for preventive migraine therapy who had a moderate to severe migraine attack. Treatment with eptinezumab vs placebo during a migraine attack resulted in median time to headache pain freedom of 4 hours vs 9 hours and median time to absence of most bothersome symptom of 2 hours vs 3 hours, respectively; both comparisons were statistically significant.

Meaning

Among patients eligible for preventive migraine therapy, treatment with intravenous eptinezumab vs placebo during an active moderate to severe migraine attack shortened time to headache and migraine symptom freedom.

Abstract

Importance

Intravenous eptinezumab, an anti–calcitonin gene-related peptide antibody, is approved for migraine prevention in adults. It has established onset of preventive efficacy on day 1 after infusion.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of and adverse events related to eptinezumab when initiated during a migraine attack.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Phase 3, multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted from November 4, 2019, to July 8, 2020, at 47 sites in the United States and the country of Georgia. Participants (aged 18-75 years) with a greater than 1-year history of migraine and migraine on 4 to 15 days per month in the 3 months prior to screening were treated during a moderate to severe migraine attack.

Interventions

Eptinezumab, 100 mg (n = 238), or placebo (n = 242), administered intravenously within 1 to 6 hours of onset of a qualifying moderate to severe migraine.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Co-primary efficacy end points were time to headache pain freedom and time to absence of most bothersome symptom (nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia). Key secondary end points were headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom at 2 hours after start of infusion. Additional secondary end points were headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom at 4 hours and use of rescue medication within 24 hours.

Results

Of 480 randomized and treated patients (mean age, 44 years; 84% female), 476 completed the study. Patients treated with eptinezumab vs placebo, respectively, achieved statistically significantly faster headache pain freedom (median, 4 hours vs 9 hours; hazard ratio, 1.54 [P < .001]) and absence of most bothersome symptom (median, 2 hours vs 3 hours; hazard ratio, 1.75 [P < .001]). At 2 hours after infusion, in the respective eptinezumab and placebo groups, headache pain freedom was achieved by 23.5% and 12.0% (between-group difference, 11.6% [95% CI, 4.78%-18.31%]; odds ratio, 2.27 [95% CI, 1.39-3.72]; P < .001) and absence of most bothersome symptom by 55.5% and 35.8% (between-group difference, 19.6% [95% CI, 10.87%-28.39%]; odds ratio, 2.25 [95% CI, 1.55-3.25]; P < .001). Results remained statistically significant at 4 hours after infusion. Statistically significantly fewer eptinezumab-treated patients used rescue medication within 24 hours than did placebo patients (31.5% vs 59.9%, respectively; between-group difference, −28.4% [95% CI, −36.95% to −19.86%]; odds ratio, 0.31 [95% CI, 0.21-0.45]; P < .001). Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 10.9% of the eptinezumab group and 10.3% of the placebo group; the most common was hypersensitivity (eptinezumab, 2.1%; placebo, 0%). No treatment-emergent serious adverse events occurred.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients eligible for preventive migraine therapy experiencing a moderate to severe migraine attack, treatment with intravenous eptinezumab vs placebo shortened time to headache and symptom resolution. Feasibility of administering eptinezumab treatment during a migraine attack and comparison with alternative treatments remain to be established.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04152083

This randomized clinical trial assesses the effect of intravenous eptinezumab vs placebo on times to headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom (nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia) among patients experiencing a moderate to severe migraine attack.

Introduction

Migraine manifests as recurrent episodes of moderate to severe headache that, when untreated, typically last between 4 and 72 hours, and are associated with nausea and sensory disruption such as photophobia and phonophobia.1 In a recent study, 34.3% of patients had an insufficient response to acute migraine treatment and were found to have more severe symptoms, higher disability levels, and a numerically greater number of headache days per month compared with responders.2 Given the risk of medication overuse and progression from episodic to chronic migraine with inadequate acute treatment,3,4 there is a need for effective preventive migraine therapies with rapid onset of efficacy. Patients may continue overusing acute medication while waiting for preventive treatment to become efficacious after initiation; for these patients, a preventive treatment with a short time to onset of efficacy would be beneficial.

Eptinezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to and inhibits the activity of calcitonin gene-related peptide, is indicated for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults in the United States.5,6 As administered by intravenous infusion, eptinezumab is 100% bioavailable and reaches maximum plasma concentration in approximately 30 minutes, corresponding to the end of infusion.5,7 In preventive migraine trials, efficacy with eptinezumab was observed on day 1 following initial infusion,8 the earliest time point available for the evaluation of migraine prevention. The magnitude of efficacy observed on day 1 was sustained over the primary 12-week dosing interval9,10,11 and persisted or increased with additional dosing.12,13

The purpose of the RELIEF study was to assess the efficacy and safety of eptinezumab compared with placebo when infused during an active migraine attack in patients with a monthly migraine frequency rendering them eligible for preventive migraine treatment per current guidelines.14,15

Methods

This was a phase 3, multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in the United States (42 sites) and the country of Georgia (5 sites) between November 2019 and July 2020. The study was conducted in accordance with standards of Good Clinical Practice as defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation and all applicable federal and local regulations. All study documentation was approved by the local review board at each site or by a central institutional review board or ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2, respectively.

Patients

Eligible patients included women and men aged 18 to 75 years (inclusive) with a greater than 1-year history of migraine (International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition [ICHD-3] criteria1) with or without aura, onset of first migraine before age 50 years, migraine on 4 to 15 days per month in the 3 months prior to screening (to ensure that patients who could be considered candidates for preventive treatment were enrolled), and previous or active use of triptans as acute treatment for migraine. Patients must have been headache-free, without any acute migraine treatment use, for at least 24 hours prior to the onset of a qualifying migraine (defined using ICHD-3 criteria).1 Race and ethnicity were self-identified by patients based on fixed categories and were captured in alignment with guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the eAppendix in Supplement 3.

Study Design

The total study duration was approximately 4 to 12 weeks, including a screening period of up to 8 weeks, with clinic visits occurring at screening, on day 0 (dosing day), and at week 4 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Study sites attempted to contact patients weekly between screening and day 0 via a mobile application or phone call. The Qualifying Migraine Assessment, which was based on ICHD-3 criteria1 for migraine with or without aura, was completed by an investigator at the day 0 visit prior to randomization and assessed headache characteristics, symptoms, time of migraine onset, and absence of acute medication use within the previous 24 hours. Patients selected their most bothersome symptom based on the qualifying migraine at the time of randomization.

Randomization

Patients were registered in an electronic data capture system and were randomly assigned to treatment via an interactive web/voice randomization system operated by the clinical study site’s unblinded pharmacist or designee. Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of intravenous eptinezumab [Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals Inc] or placebo in a 1:1 ratio, with randomization stratified by concomitant preventive migraine treatment (yes vs no) and region (United States vs country of Georgia) using a block size of 4. Randomization and dosing were triggered by a qualifying migraine and occurred on day 0.

Interventions

Treatment with either 100 mg of eptinezumab or placebo (total volume of 100 mL with 0.9% saline) was administered intravenously over a period of 30 minutes (up to 45 minutes) on day 0 by a blinded investigator or designee within 1 to 6 hours of the qualifying migraine onset. The selection of the eptinezumab 100-mg dose level was based on data from PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2, in which this dose level provided a meaningful magnitude of efficacy on day 1 that was sustained throughout the first month and beyond.8,10,11 Placebo was formulated with the same excipients as eptinezumab without the active ingredient. Patients remained at the site for 4 hours after start of infusion to ensure proper data collection through the early study time points.

No rescue medication (defined as any acute medication to treat migraine or migraine-associated symptoms) could be used in the 24-hour period prior to receiving study treatment or within 2 hours of infusion start. Two hours after start of infusion, patients who did not have adequate response were permitted to take their own rescue medication or were provided with suitable rescue medication by the study site. Inadequate response was defined as continuing to experience moderate or severe headache pain, continuing to experience significant migraine-associated symptoms, or, after initial migraine relief at 2 hours, having headache or migraine-associated symptoms return within 2 to 48 hours after dosing.

Outcomes

Co-primary efficacy end points were time to headache pain freedom and time to absence of most bothersome symptom (patient-selected from among nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia prior to dosing for the migraine being treated). Hazard ratios were chosen as the primary analysis method to compare the probability of outcome events between eptinezumab and placebo in order to determine if patients receiving eptinezumab achieved faster response than patients receiving placebo. Key secondary efficacy end points were headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom at 2 hours after start of infusion. Additional secondary efficacy end points were headache pain freedom at 4 hours, absence of most bothersome symptom at 4 hours, and use of rescue medication within 24 hours. Exploratory efficacy end points included time to headache pain relief; headache pain freedom at 2 hours with sustained freedom for 24 and 48 hours; use of rescue medication by 48 hours; and time to next migraine (beginning ≥3 days [72 hours] after dosing).

The incidence, nature, and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), including TEAEs of special interest, and results of clinical laboratory assessments, vital sign measurements, electrocardiograms, and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale were collected. Verbatim descriptions of all adverse events were coded to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 20.1 and classified by system organ class and preferred term. Full definitions of each end point are provided in the eAppendix in Supplement 3.

Sample Size

Calculations indicated that approximately 450 patients (225 per group) would provide at least 90% power to detect a hazard ratio (eptinezumab:placebo) of 1.359 favoring eptinezumab at the α = .05 significance level for both co-primary end points. There were no methodologically similar studies of preventive migraine treatment studied in an acute migraine trial setting or with time to event as the primary analysis method. Given the lack of any previous research to define a minimum clinically important difference for this outcome in this setting, the power assumptions were initially based on expected rates for the key secondary end points, which were chosen through assessment of assumptions from recently published acute migraine trials. Based on these numbers, evaluations of possible achievement in terms of hazard ratios were then made, and this led to a final decision regarding the hazard ratio used in the power calculations.

Statistical Analyses

Efficacy was evaluated in the full analysis set, defined as all randomized patients who received eptinezumab or placebo, with data summarized by randomized treatment group. The safety population included all patients who received eptinezumab or placebo, analyzed by treatment received. All patients received their randomized treatment; therefore, the full analysis set and safety populations comprised the same patients in each treatment group.

A serial procedure was used to account for multiplicity associated with multiple end points to ensure that the type I error did not exceed 5%. The eptinezumab group was compared with the placebo group using 2-sided tests and a α = .05 significance level, starting with the co-primary end points. Study success was defined as when both time to headache pain freedom and time to absence of most bothersome symptom were statistically significant at the α = .05 significance level. If both co-primary efficacy end points demonstrated statistical significance (P < .05), then testing continued hierarchically to the key secondary end points (headache pain freedom at 2 hours followed by absence of most bothersome symptom at 2 hours) then to the additional secondary end points (headache pain freedom at 4 hours, absence of most bothersome symptom at 4 hours, and use of rescue medication within 24 hours) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3).

Time to headache pain freedom and time to absence of most bothersome symptom were compared between the eptinezumab and placebo groups using a Cox proportional hazard model with treatment as covariate, stratified for use of preventive migraine treatment and for region, using the Efron method of tie handling. The hazard ratio between the treatment groups and its 95% confidence interval were determined from this model; the hazard ratio provides a relative event rate for each group and can be used to compare different groups.16 Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to graphically illustrate the data; curves were generated to indicate the time-to-event data and to illustrate the time points at which individual patients had an event or were censored.16 The proportionality assumption was visually inspected in each stratum using Kaplan-Meier plots, with no violations detected. For the primary analysis, censoring occurred at the time point of first rescue medication reporting in patients who took rescue medication without having reported pain freedom/absence of most bothersome symptom at an earlier time point. For patients who did not report pain freedom/absence of most bothersome symptom during the 48 hours after the start of the infusion and who did not report taking rescue medication at any time point, administrative censoring was applied at the time of their last entry in an electronic diary.

The times to headache pain relief and next migraine were summarized using the same Cox regression model and Kaplan-Meier methodology as the co-primary end points, as applicable. For the other end points, treatment groups were compared at each of the time points using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, stratified for use of preventive migraine treatment and region. The estimations of treatment difference, odds ratio, and associated confidence intervals were calculated. Patients were censored at the time of their last entry in the electronic diary.

If the pain or most bothersome symptom assessment was missing at a given time point, it was assumed that no pain freedom or no absence of most bothersome symptom was obtained for this time point and that rescue medication was not used at this time point. Four sensitivity analyses based on the primary analysis were conducted for time to headache pain freedom and time to absence of most bothersome symptom. In the first analysis, rescue medication censoring was removed; therefore, the time value for each patient was censored only if the patient did not report pain freedom/absence of most bothersome symptom at all during the 48 hours after start of infusion. In the second analysis, the data were calculated based on the requirement for an event to persist for at least 30 minutes; for example, any patient reporting pain freedom at 2 hours but reporting pain recurrence at 2.5 hours was still categorized as at risk. In the third and fourth analyses, only data up to and including the 12-hour or the 4-hour assessment, respectively, were used; rules for censoring were identical to those for the primary analysis except that time values were administratively censored at 12 hours or 4 hours, respectively, instead of at 48 hours.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc), version 9.4 or later.

Results

Study Population

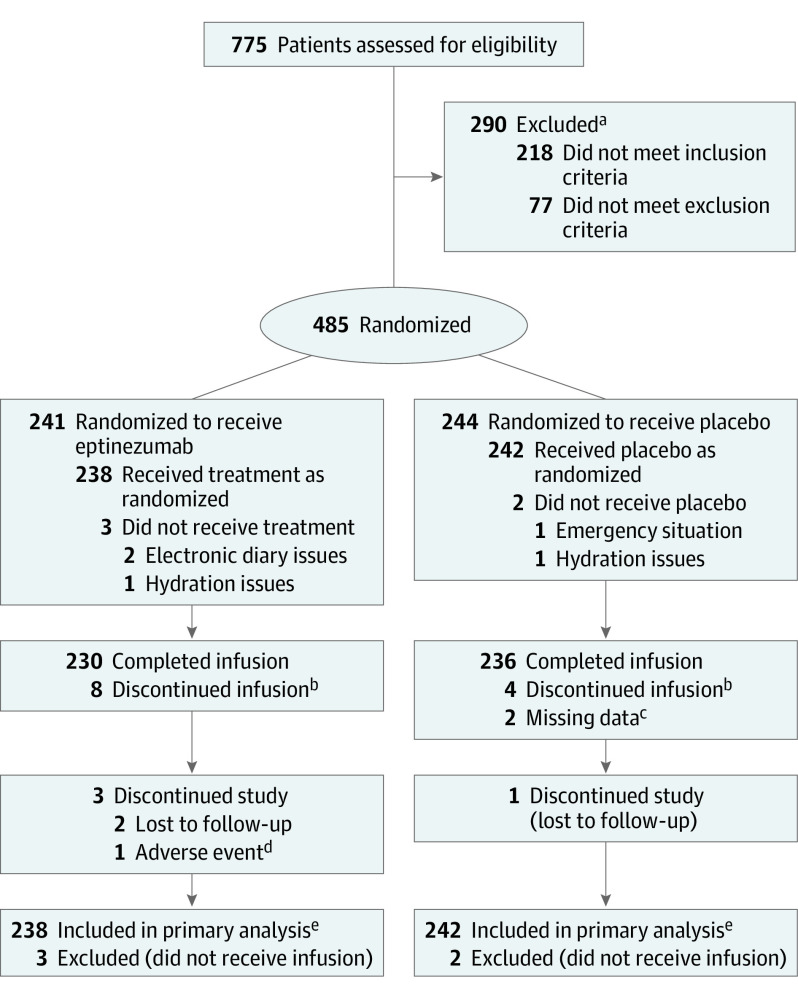

A total of 480 patients were candidates for preventive therapy, met inclusion and exclusion criteria, and were randomly assigned to treatment with 100 mg of eptinezumab (n = 238) or placebo (n = 242). Patients completing the study included 235 (98.7%) treated with eptinezumab and 241 (99.6%) who received placebo; of the 4 patients who discontinued the study early, 3 (eptinezumab, n = 2; placebo, n = 1) were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). At all time points through hour 6, the rates of missing electronic diary data were less than 3% overall; missing data rates ranged from 2% to 7% overall from the 9-hour through 48-hour time points. Baseline demographic data and patient clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Recruitment, Randomization, and Patient Flow in the RELIEF Trial.

aThere were 38 reasons for the 290 screening failures (patients could have >1 reason for failure); the most common (≥10 patients) were (1) not willing and/or able to receive infusion with study drug during a qualifying migraine attack within 8 weeks of screening visit (n = 153); (2) not willing and/or able to adhere to scheduled clinic visits and complete all study-related procedures (n = 29); (3) use of acetaminophen, aspirin, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for any indication for ≥15 days per month in each of the 3 months prior to screening (n = 13); and (4) women of childbearing potential and men with partners of childbearing potential not agreeing to use adequate contraception for the duration of the study (n = 10).

bReasons infusion was discontinued in the eptinezumab group included adverse events (n = 3), a patient needing to use the restroom (n = 2), difficulty finding vein/infiltration/repositioning (n = 1), electronic diary issues (n = 1), and a fire alarm (n = 1). Reasons infusion was discontinued in the placebo group included adverse events (n = 2) and line occlusion/bag running dry and inability to flush (n = 2).

cThe 2 patients with missing data for infusion completion underwent infusion for 30 and 31 minutes.

dAdverse event was an upper respiratory tract infection that began on day 32 after the 28-day study (captured in the study completion/termination form) and was not considered related to study drug.

eAll treated patients received the treatment to which they were randomized; therefore, the full analysis set and safety population comprise the same patients in each treatment group.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics (Safety Population).

| Characteristics | Eptinezumab (n = 238) | Placebo (n = 242) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 44.9 (12.0) | 44.1 (12.1) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 202 (84.9) | 201 (83.1) |

| Male | 36 (15.1) | 41 (16.9) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 200 (84.0) | 213 (88.0) |

| Black or African American | 30 (12.6) | 19 (7.9) |

| Asian | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Multiple | 3 (1.3) | 4 (1.7) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, No. (%) | 29 (12.2) | 31 (12.8) |

| Region, No. (%) | ||

| United States | 167 (70.2) | 170 (70.2) |

| Country of Georgia | 71 (29.8) | 72 (29.8) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)a | 27.0 (4.5) | 26.6 (4.4) |

| Using concomitant preventive medication, No. (%) | 39 (16.4) | 40 (16.5) |

| History of chronic migraine, No. (%)b | 25 (10.5) | 27 (11.2) |

| Monthly migraine days, mean (SD)c | 7.2 (2.7) | 7.2 (2.6) |

| Duration of migraine prior to infusion start, mean (SD), hd | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.7 (1.0) |

| Severity of headache pain, No. (%) | ||

| Moderate | 110 (46.2) | 117 (48.3) |

| Severe | 128 (53.8) | 123 (50.8) |

| Most bothersome symptom, No. (%) | ||

| Photophobia | 114 (47.9) | 114 (47.1) |

| Nausea | 78 (32.8) | 79 (32.6) |

| Phonophobia | 46 (19.3) | 47 (19.4) |

| Presence of photophobia, No. (%) | 235 (98.7) | 229 (94.6) |

| Presence of phonophobia, No. (%) | 204 (85.7) | 191 (78.9) |

| Presence of nausea, No. (%) | 180 (75.6) | 169 (69.8) |

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Migraine history information was collected at the screening visit by investigators through medical records; if medical records could not be obtained, history was confirmed via patient interview to obtain sufficient information to confirm that all eligibility criteria were met.

Patients self-reported the average number of monthly migraine days during the 3 months prior to screening.

Duration was calculated as the difference between the study drug infusion start date and time and the day 0 headache start date and time.

Co-primary End Points

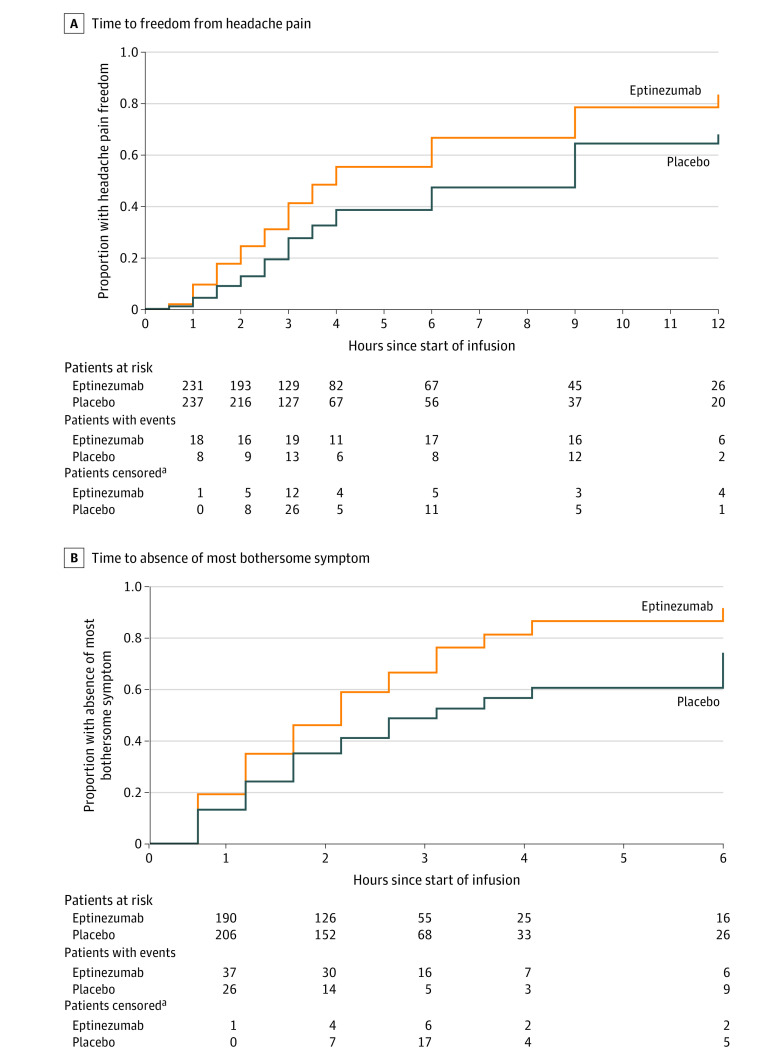

The hazard ratio for the between-group difference in time to headache pain freedom was 1.54 (95% CI, 1.20-1.98) in favor of eptinezumab (P < .001). The median time after start of infusion to headache freedom was 4 hours for eptinezumab-treated patients and 9 hours for placebo patients. The hazard ratio for the between-group difference in time to absence of most bothersome symptom was 1.75 (95% CI, 1.41-2.19) in favor of eptinezumab (P < .001). The median time to absence of most bothersome symptom was 2 hours for eptinezumab-treated patients and 3 hours for placebo patients. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the probability of achieving headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom at each time point are shown in Figure 2. Sensitivity analyses are presented in eFigure 3 in Supplement 3; the results all supported the primary analysis. For the sensitivity analysis in which patients were not censored for use of rescue medication, the hazard ratio for the between-group difference in time to headache pain freedom was 1.29 (95% CI, 1.08-1.56) in favor of eptinezumab (P = .006) and for time to absence of most bothersome symptom was 1.49 (95% CI, 1.24-1.80) in favor of eptinezumab (P < .001).

Figure 2. Co-primary End Points: Time to Headache Pain Freedom and Absence of Most Bothersome Symptom in the Full Analysis Set.

For headache pain freedom, the median observation time was 2 hours (interquartile range [IQR], 1-2.5 hours) for the eptinezumab group and 2.5 hours (IQR, 1-3 hours) for the placebo group. For absence of most bothersome symptom, the median observation time was 3 hours (IQR, 2-6 hours) for the eptinezumab group and 3 hours (IQR, 2.5-4 hours) for the placebo group. Median times to headache pain freedom were 4.0 (interquartile range [IQR], 2.5-12.0) hours in the eptinezumab group and 9.0 (IQR, 3.0-48.0) hours in the placebo group; median times to absence of most bothersome symptom were 2.0 (IQR, 1.0-3.5) hours and 3.0 (IQR, 1.5-12.0) hours, respectively.

aAll censoring of patients was due to rescue medication use.

Secondary Efficacy End Points

Results for the secondary efficacy end points are summarized in Table 2 and in eFigure 4 in Supplement 3. The odds ratio of achieving 2-hour headache pain freedom was 2.27 (95% CI, 1.39-3.72; P < .001) in favor of eptinezumab (23.5%) vs placebo (12.0%; difference, 11.6%; 95% CI, 4.78%-18.31%). The odds ratio of achieving 2-hour absence of most bothersome symptom was 2.25 (95% CI, 1.55-3.25; P < .001) in favor of eptinezumab (55.5%) vs placebo (35.8%; difference, 19.6%; 95% CI, 10.87%-28.39%). Results at 4 hours also statistically significantly favored eptinezumab compared with placebo for headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom. The odds ratio of rescue medication use within 24 hours was 0.31 (95% CI, 0.21-0.45; P < .001) favoring eptinezumab (31.5%) vs placebo (59.9%; difference, −28.4%; 95% CI, −36.95% to −19.86%).

Table 2. Summary of Co-primary, Secondary, and Select Exploratory End Points (Full Analysis Set).

| End points | Eptinezumab (n = 238) | Placebo (n = 242) | Difference, % (95% CI) | Ratio of eptinezumab to placebo, HR or OR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co–primary end points, median (IQR), h | |||||

| Time to headache pain freedom | 4.0 (2.5-12.0) | 9.0 (3.0-48.0) | HR, 1.54 (1.20-1.98) | <.001 | |

| Time to absence of most bothersome symptom | 2.0 (1.0-3.5) | 3.0 (1.5-12.0) | HR, 1.75 (1.41-2.19) | <.001 | |

| Sequential secondary end points, No. (%)b | |||||

| Headache pain freedom at 2 h | 56 (23.5) | 29 (12.0) | 11.6 (4.78 to 18.31) | OR, 2.27 (1.39-3.72) | <.001 |

| Absence of most bothersome symptom at 2 h | 132 (55.5) | 86/240 (35.8) | 19.6 (10.87 to 28.39) | OR, 2.25 (1.55-3.25) | <.001 |

| Headache pain freedom at 4 h | 111 (46.6) | 64 (26.4) | 20.2 (11.76 to 28.62) | OR, 2.43 (1.66-3.56) | <.001 |

| Absence of most bothersome symptom at 4 h | 155 (65.1) | 90/240 (37.5) | 27.6 (19.01 to 36.24) | OR, 3.07 (2.12-4.46) | <.001 |

| Use of rescue medication within 24 h | 75 (31.5) | 145 (59.9) | −28.4 (−36.95 to −19.86) | OR, 0.31 (0.21-0.45) | <.001 |

| Exploratory end pointsc | |||||

| Time to headache pain relief, median (IQR), h | 1.5 (1.0-3.5) | 3.5 (1.5-12.0) | HR, 1.91 (1.53-2.38) | <.001 | |

| Patients achieving headache pain relief, No. (%) | |||||

| 2 h after infusion start | 152 (63.9) | 98 (40.5) | 23.4 (14.68 to 32.06) | ||

| 4 h after infusion start | 167 (70.2) | 97 (40.1) | 30.1 (21.61 to 38.57) | ||

| Sustained headache pain freedom, No. (%) | |||||

| From 2 h through 24 h | 41 (17.2) | 14 (5.8) | 11.4 (5.81 to 17.07) | OR, 3.43 (1.81-6.51) | <.001 |

| From 2 h through 48 h | 39 (16.4) | 11 (4.5) | 11.8 (6.46 to 17.23) | OR, 4.15 (2.07-8.35) | <.001 |

| Use of rescue medication within 48 h, No. (%) | 83 (34.9) | 154 (63.6) | −28.8 (−37.33 to −20.20) | OR, 0.30 (0.21-0.44) | <.001 |

| Time to next migraine, median (IQR), d | 10.0 (3.0-27.0) [n = 234] | 5.0 (2.0-13.0) [n = 236] | HR, 0.60 (0.49-0.73) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio.

Hazard ratios indicate the likelihood of experiencing an event at any particular time point with eptinezumab compared with placebo. Odds ratios indicate the likelihood of experiencing an event at a specific time point with eptinezumab compared with placebo.

The statistical hierarchy is outlined in eFigure 2 in Supplement 3.

P values for exploratory end points were not adjusted for multiplicity.

Exploratory Efficacy End Points

Results for the exploratory efficacy end points are summarized in Table 2. The median time to headache pain relief was 1.5 hours for patients who received eptinezumab and 3.5 hours for patients who received placebo (hazard ratio, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.53-2.38; P < .001). The odds ratio of reporting sustained headache pain freedom from 2 hours through 24 hours was 3.43 (95% CI, 1.81-6.51; P < .001) in favor of eptinezumab (17.2%) vs placebo (5.8%; difference, 11.4%; 95% CI, 5.81%-17.07%) and from 2 hours through 48 hours was 4.15 (95% CI, 2.07-8.35; P < .001) in favor of eptinezumab (16.4%) vs placebo (4.5%; difference, 11.8%; 95% CI, 6.46%-17.23%). The odds of using rescue medication within 48 hours were similar to that within 24 hours (eptinezumab, 34.9%; placebo, 63.6%; difference, −28.8% [95% CI, −37.33% to −20.20%]; odds ratio, 0.30 [95% CI, 0.21-0.44]; P < .001). Median time to next migraine was 10 days with eptinezumab vs 5 days with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.49-0.73; P < .001).

Adverse Events

A summary of TEAEs is provided in Table 3. The most frequently reported TEAE in the eptinezumab group was hypersensitivity (ie, allergic reaction; 5/238 [2.1%]). Two of the hypersensitivity events were mild in severity, 2 were moderate, and 1 was severe; none were considered serious. Three of the events occurred during the infusion (12-18 minutes after start) and the remaining 2 occurred after the infusion was complete (6 and 40 minutes after end). The severe hypersensitivity event led to study drug interruption. All of the hypersensitivity events were considered related to study drug and were resolved with standard medical treatment. No serious TEAEs were reported in either treatment group.

Table 3. Summary of TEAEs (Safety Population).

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Eptinezumab (n = 238) | Placebo (n = 242) | |

| Any TEAEa | 26 (10.9) | 25 (10.3) |

| Any TEAE of special interest | 10 (4.2) | 3 (1.2) |

| Any TEAE leading to infusion interruption | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Infusion site extravasation | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Hypersensitivityb | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Serious TEAEs | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs in >1 patient in either group | ||

| Hypersensitivityb | 5 (2.1) | 0 |

| Influenza | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Infusion site extravasation | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 (0.8) |

| Nausea | 0 | 2 (0.8) |

| TEAEs of special interest | ||

| Hypersensitivityb | 5 (2.1) | 0 |

| Infusion site extravasation | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Cough | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Allergic pruritus | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Syncope | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Increased transaminase levels | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Verbatim descriptions of all adverse events were coded to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 20.1, and classified by system organ class and preferred term. Investigators monitored the occurrence of adverse events for each patient from the time of informed consent through the course of the study. Adverse events may have been reported by a patient, a caregiver, or the investigative site through site personnel open-ended questioning, physical examination, laboratory tests, documentation in medical records, or other means.

TEAEs coded to the preferred term hypersensitivity were based on the sponsor’s established framework for evaluating individual symptoms or symptom constellations occurring on days of infusion.11 The clinical presentation of each of these events was reported as allergic reaction.

Discussion

Among patients eligible for preventive migraine therapy experiencing a moderate to severe migraine attack, treatment with 100 mg of intravenous eptinezumab vs placebo provided statistically significantly shorter time to headache pain freedom and time to absence of most bothersome symptom when administered during a moderate to severe migraine attack.

Eptinezumab met statistical significance vs placebo on all 7 prespecified primary and secondary end points included in the statistical hierarchy. Treatment with eptinezumab more frequently resolved headache pain and most bothersome symptom at 2 hours and 4 hours after the start of the 30-minute infusion and led to less frequent rescue medication use. In addition, eptinezumab provided faster time to headache pain relief, sustained headache pain freedom, and delayed time to next migraine. Adverse events reported in this study were consistent with previous clinical trials of eptinezumab for migraine prevention,9,10,11 with the most common TEAE being hypersensitivity in 2.1% of patients in the eptinezumab group.

Patients with migraine have previously had to wait several weeks for the effect of their preventive medications to manifest,17 often resulting in extended periods of disability or reduced functioning, potential unscheduled visits to clinics or emergency departments to obtain migraine relief, and risk of potential overuse of acute medication. While data from previously published studies demonstrated preventive migraine efficacy with eptinezumab vs placebo on the day after initial infusion,8,10,11 data from this study demonstrated efficacy with eptinezumab vs placebo on the same day when initiated during a migraine attack. Combined with the results of secondary end points—reduced need for acute or rescue medication for the qualifying migraine attack, sustained efficacy through the 24- and 48-hour time points, and delayed time to next migraine—results of the current study demonstrate that an active migraine would not be an obstacle for initiating preventive treatment with eptinezumab. Patients experiencing high-frequency episodic migraine and chronic migraine have a substantial number of monthly migraine days,1 making it likely that an active migraine may be present on days when patients receive preventive treatment. Overall, previous preventive studies of eptinezumab8,10,11 considered together with the current study data suggest that intravenous eptinezumab has the potential to provide a therapeutic bridge between the acute and preventive treatment needs of patients with migraine.

Results from the current study indicate that eptinezumab may provide additional infusion-day benefits while delaying the onset of a new migraine over the 4 weeks following treatment. Rates of 2-hour headache pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom observed with eptinezumab vs placebo in this study appear similar or numerically better than results reported from trials of recently approved acute oral treatments in similarly designed studies.18 These findings may be limited in clinical practice due to practical challenges (eg, access to an infusion center, insurance coverage issues), and the full clinical usefulness of these findings has yet to be elucidated, with further study needed.

Eptinezumab is not an acute migraine treatment; however, using the acute migraine trial design allowed for the capture of same-day infusion efficacy data with eptinezumab, which was not possible with the design of the previous preventive migraine studies. To our knowledge to date, eptinezumab is the only anti–calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody preventive treatment that has been evaluated when initiated during a migraine attack. When coupled with the established preventive efficacy of eptinezumab, it raises the potential of initiating effective treatment preventing future attacks of migraine with the added benefit of alleviating an active migraine attack.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study did not include a run-in period to define the preceding migraine frequency but paralleled clinical practice in measuring migraine days based on a history of 4 to 15 migraine days per month in the 3 months prior to screening. This requirement ensured the enrollment of patients who could be considered candidates for preventive treatment in line with current guidance,14,15,19 but was less stringent than controlled daily diaries to establish migraine frequency. Second, this inclusion criterion (4-15 migraine days per month) also diverged from current guidance for studies of acute migraine treatment—which exclude patients with chronic migraine (limiting the population to 2-8 migraine days per month)20,21—resulting in a population with more frequent and severe migraine than those who are included in acute migraine trials and underscoring that the methodology of this study was intended instead to show that eptinezumab could be used to treat and prevent migraine in the population of patients eligible for preventive treatment. Third, the generalizability of these study results may be limited due to the high proportions of female, White, and non-Hispanic or non-Latino patients enrolled. Fourth, this study did not include an active control, precluding direct comparisons between eptinezumab and other migraine treatments administered under these conditions. Fifth, the practical challenges of delivering eptinezumab during an acute migraine attack (eg, access to an infusion center, insurance coverage issues) may be a limitation to the clinical usefulness of this study.

Conclusions

Among patients eligible for preventive migraine therapy experiencing a moderate to severe migraine attack, treatment with intravenous eptinezumab vs placebo shortened time to headache and symptom resolution. Feasibility of administering eptinezumab treatment during a migraine attack and comparison with alternative treatments remain to be established.

Study Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eFigure 1. RELIEF Study Design

eFigure 2. RELIEF Statistical Testing Hierarchy

eFigure 3. Results of Sensitivity Analyses for (A) Time to Headache Pain Freedom and (B) Time to Absence of Most Bothersome Symptom (Full Analysis Set)

eFigure 4. Secondary Efficacy Endpoints (Full Analysis Set)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombard L, Ye W, Nichols R, Jackson J, Cotton S, Joshi S. A real-world analysis of patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and level of impairment in patients with migraine who are insufficient responders vs responders to acute treatment. Headache. 2020;60(7):1325-1339. doi: 10.1111/head.13835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buse DC, Greisman JD, Baigi K, Lipton RB. Migraine progression: a systematic review. Headache. 2019;59(3):306-338. doi: 10.1111/head.13459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres-Ferrús M, Ursitti F, Alpuente A, et al. ; School of Advanced Studies of European Headache Federation . From transformation to chronification of migraine: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):42-42. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01111-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Martinez LF, Raport CJ, Ojala EW, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of ALD403, a potent neutralizing humanized monoclonal antibody against the calcitonin gene-related peptide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2020;374(1):93-103. doi: 10.1124/jpet.119.264671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vyepti [package insert]. Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals Inc; 2020.

- 7.Baker B, Schaeffler B, Beliveau M, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and exposure-response analysis of eptinezumab in the treatment of episodic and chronic migraine. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8(2):e00567. doi: 10.1002/prp2.567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodick DW, Gottschalk C, Cady R, Hirman J, Smith J, Snapinn S. Eptinezumab demonstrated efficacy in sustained prevention of episodic and chronic migraine beginning on day 1 after dosing. Headache. 2020;60(10):2220-2231. doi: 10.1111/head.14007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Silberstein S, et al. Eptinezumab for prevention of chronic migraine: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(9):1075-1085. doi: 10.1177/0333102419858355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia. 2020;40(3):241-254. doi: 10.1177/0333102420905132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, et al. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology. 2020;94(13):e1365-e1377. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silberstein S, Diamond M, Hindiyeh NA, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of chronic migraine: efficacy and safety through 24 weeks of treatment in the phase 3 PROMISE-2 (Prevention of Migraine via Intravenous ALD403 Safety and Efficacy-2) study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01186-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TR, Janelidze M, Chakhava G, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: sustained effect through 1 year of treatment in the PROMISE-1 study. Clin Ther. 2020;42(12):2254-2265. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Headache Society . The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al. ; European Federation of Neurological Societies . EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine—revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):968-981. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rich JT, Neely JG, Paniello RC, Voelker CC, Nussenbaum B, Wang EW. A practical guide to understanding Kaplan-Meier curves. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(3):331-336. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21(4):973-989. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashina M. Migraine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1866-1876. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1915327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pringsheim T, Davenport W, Mackie G, et al. ; Canadian Headache Society Prophylactic Guidelines Development Group . Canadian Headache Society guideline for migraine prophylaxis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39(2)(suppl 2):S1-S59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Food and Drug Administration . Migraine: Developing Drugs for Acute Treatment: Guidance for Industry. Published February 2018. Accessed September 3, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/89829/download

- 21.Diener HC, Tassorelli C, Dodick DW, et al. ; International Headache Society Clinical Trials Standing Committee . Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of acute treatment of migraine attacks in adults: fourth edition. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(6):687-710. doi: 10.1177/0333102419828967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eFigure 1. RELIEF Study Design

eFigure 2. RELIEF Statistical Testing Hierarchy

eFigure 3. Results of Sensitivity Analyses for (A) Time to Headache Pain Freedom and (B) Time to Absence of Most Bothersome Symptom (Full Analysis Set)

eFigure 4. Secondary Efficacy Endpoints (Full Analysis Set)

Data Sharing Statement