Abstract

Ventricular noncompaction is a rare, heterogeneous cardiomyopathy characterized by marked trabeculations and deep intertrabecular spaces with clinical sequelae of heart failure, arrhythmias, and cardioembolic events. In this article, we describe a patient with isolated right ventricular noncompaction who presented with submassive pulmonary embolism, which was managed with long-term direct oral anticoagulation.

Keywords: ventricular noncompaction, pulmonary embolism

Introduction

Isolated right ventricular noncompaction (iRVNC) is an exceedingly rare cardiomyopathy resulting from the arrested development of endomyocardial morphogenesis with potentially devastating sequelae of intractable heart failure, lethal arrhythmias, and systemic cardioembolic events. 1 Ventricular noncompaction (VNC) is emerging as an incipient cause of heart failure in both pediatric and adult populations. It is often associated with other congenital heart defects, most notably outflow obstructive lesions and coronary anomalies. 2

Ventricular noncompaction typically displays a dense trabecular meshwork with deep intertrabecular recesses, with the most commonly involved site being the left ventricle (LV) and the right ventricle (RV) only in a paucity of cases.3,4 Diagnosis is usually established with complementary advanced imaging techniques of transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), cardiac computed tomography angiography (cCTA), and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI).

We describe a patient with iRVNC who presented with submassive pulmonary embolism (PE), managed with long-term direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC).

Case Report

A 52-year-old Caribbean-Black male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease stage 2 presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath during the preceding week. He had no significant social, travel, or family history and was previously prescribed low-dose atenolol, nifedipine, and metformin. His vital signs indicated systolic blood pressures of 144 mm Hg, heart rate of 123 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 19 breaths/minute with an oxygen saturation of 92% on supplemental oxygen. His physical examination revealed an elevated jugular venous pulse of 10 cm of H2O, 4/6 holosystolic murmur with a prominent P2 auscultated at the left lower sternal border, bilateral basal crackles, and pitting edema to the tibial tuberosities.

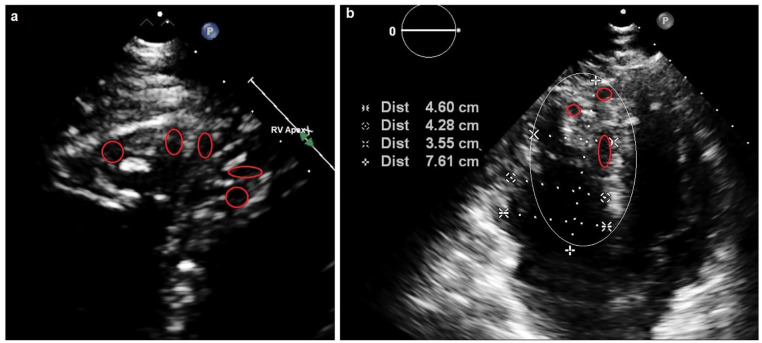

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgM antibody serologies (Abbott Laboratories) on arrival to the emergency department were negative. A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia with right bundle branch block (RBBB) and right axis deviation. A portable chest radiograph displayed mild cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema with Kerley B lines and bilateral small pleural effusions. Routine investigations were performed (Table 1). A bedside 2-dimensional TTE (2D-TTE) demonstrated mild global left ventricular hypokinesis with an estimated ejection fraction (EF) of 40% to 45%, with severe right ventricular dilation and dysfunction with evidence of both pressure and volume overload. There was also moderate-severe tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension with mean right ventricular systolic pressures of 56 mm Hg (Table 2). The RV appeared to have marked trabeculations with deep sinusoidal recesses and crypts, whereas the LV displayed mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Routine Investigations.

| Tests performed | Result | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | ||

| Hemoglobin | 12.2 g/dL | 14.0-17.5 g/dL |

| White cell count | 7.1 × 109/L | 4.5-11.0 × 109/L |

| Platelet count | 283 × 103/µL | 156-373 × 103/µL |

| Comprehensive metabolic panel | ||

| Serum sodium | 136 mmol/L | 135-145 mmol/L |

| Serum potassium | 4.2 mmol/L | 3.5-5.1 mmol/L |

| Serum bicarbonate | 22 mmol/L | 22-26 mmol/L |

| Serum creatinine | 1.65 mg/dL | 0.5-1.2 mg/dL |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 28 mg/dL | 3-20 mg/dL |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 75 IU/L | 20-60 IU/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 67 IU/L | 5-40 IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 1.2 mg/dL | 0.2-1.2 mg/dL |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 144 IU/L | 40-129 IU/L |

| Albumin | 4.4 g/dL | 3.5-5.5 g/dL |

| Albumin-corrected calcium | 10.2 mg/dL | 9.6-11.2 mg/dL |

| Magnesium | 1.8 mg/dL | 1.6-2.3 mg/dL |

| Phosphorous | 3.3 mg/dL | 2.5-6.5 mg/dL |

| Fasting blood sugar | 105 mg/dL | 60-120 mg/dL |

| Cardiac profile | ||

| Glycosylated hemoglobin | 6.7% | 4.3% to 6.5% |

| Fasting lipid panel | ||

| Cholesterol | 252 mg/dL | 170-200 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | 202 mg/dL | 40-150 mg/dL |

| High-density lipoprotein | 42 mg/dL | 40-60 mg/dL |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 190 mg/dL | 60-130 mg/dL |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone | 4.12 mU/L | 0.5-5.0 mU/L |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 17 mm/h | 0-22 mm/h |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein | 3.2 mg/dL | 0.0-1.0 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 2812 ng/mL | <500 ng/mL |

| N-terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide | 3153 pg/mL | ≤300 pg/mL |

| Creatine kinase | 252 U/L | 30-170 U/L |

| Creatine kinase MB | 12 U/L | <20 U/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 479 U/L | 313-618 U/L |

| High sensitivity troponin I | 1.68 ng/mL | 0.0-0.15 ng/mL |

Table 2.

Right Ventricle Echocardiographic Parameters.

| Admission | Follow-up at 6 months | |

|---|---|---|

| Chamber dimensions | ||

| RV wall thickness in subcostal view | 2.4 cm | 2.0 cm |

| RVOT diameter in PLAX view | 4.2 cm | 3.1 cm |

| Systolic function | ||

| TAPSE | 1.1 cm | 1.5 cm |

| Pulsed Doppler peak annular velocity (seconds) | 8.1 cm/s | 9.0 cm/s |

| Tissue Doppler MPI | .63 | .48 |

| FAC | 28% | 36% |

| 3D-derived RVEF (%) | 34% | 45% |

| RVSP | 56 mm Hg | 35 mm Hg |

| Diastolic function | ||

| E/A ratio | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| E/E’ ratio | 16 | 6 |

| IVC diameter in subcostal view | 2.8 cm | 1.8 cm |

Abbreviations: 3D, 3-dimensional; FAC, fractional area change; IVC, inferior vena cava; MPI, myocardial performance index; PLAX, parasternal long-axis; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Figure 1.

An apical view of the right ventricle. (a) The red circles indicate the deep sinusoidal recesses with the encompassing deep trabecular meshwork. (b) The red circles indicate the recesses and crypts. The white eclipse indicates the marked right ventricular enlargement relative to the left ventricle.

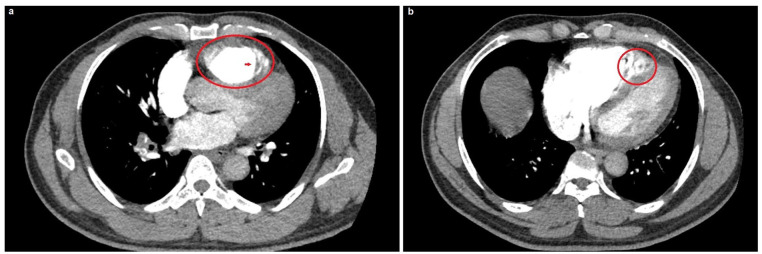

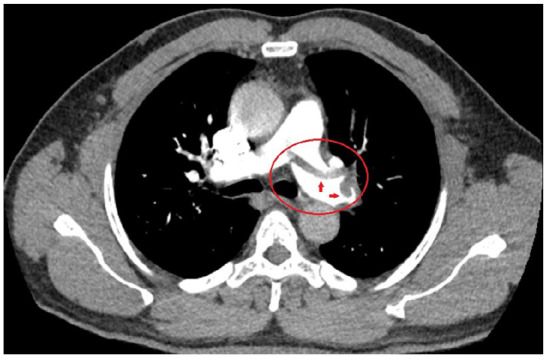

The patient was subsequently admitted to the cardiac care unit and underwent a CT-PE protocol based on his moderate Wellens’ score of 4.5, electrocardiographic changes, and markedly elevated D-dimer with a contrast-induced nephropathy protocol for his estimated glomerular filtration rate of 53 mL/min/1.73 m2. This also revealed right ventricular enlargement with prominent myocardial trabeculations and recesses similar to the bedside echocardiographic findings (Figure 2). Also, there was a relatively large, serpiginous filling defect almost occluding the left pulmonary artery, consistent with a hemodynamically significant PE (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary embolism protocol. (a) The red circle indicates right ventricular dilatation, whereas the red arrow indicates the trabecular meshwork at the right ventricular apex. (b) The red circle indicates a more focused image of the right ventricular enlargement with marked sinusoids amidst the trabecular mesh.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary embolism (PE) protocol. The red circle indicates the left pulmonary artery, which appears visually dilated, and the red arrows indicate the substantial, serpiginous thrombus burden, presumably arising from the isolated right ventricular noncompaction, consistent with a hemodynamically significant, submassive PE.

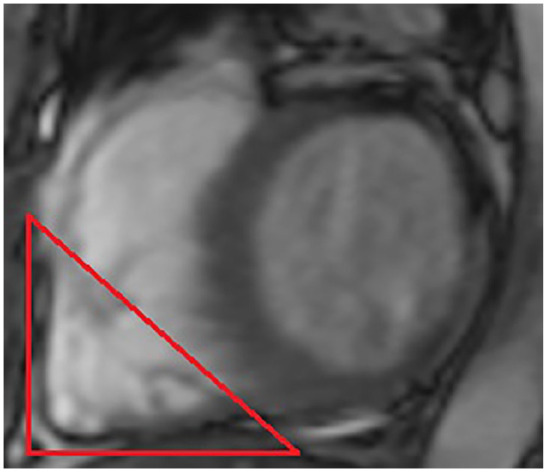

He was initiated on comprehensive, guideline-directed, optimal medical therapy for the tentative diagnoses of acute coronary syndrome with Killip class 3 heart failure, in addition to submassive PE. This included aspirin 81 mg, ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, moderate-intensity rosuvastatin 20 mg, low-dose valsartan/sacubitril 50 mg, eplerenone 25 mg, bisoprolol 2.5 mg and dapagliflozin 5 mg, trimetazidine 35 mg twice daily, and ivabradine 5 mg twice daily based on his relatively low HAS-BLED score of 2. 5 Thrombolytic therapy was not considered based on his mildly elevated hypertension and the fact that he was not en extremis. During the remainder of his 1-week hospitalization, he also underwent a contrast-enhanced cMRI scan with gadobutrol, which affirmed the iRVNC morphologic findings (Figure 4). A bilateral lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography, basic thrombophilia, and tumor marker screen were normal within their respective ranges. He stabilized hemodynamically, became clinically euvolemic, and was eventually discharged with the aforementioned antithrombotic and neurohormonal therapies. On his scheduled follow-up appointment 6 months later, the patient was asymptomatic, his d-dimer returned to normal, and his interval surveillance echocardiogram indicated an unchanged RV morphologic appearance; however, there was normalization of the left ventricular EF to 50% with markedly improved RV performance indices (Table 2). Outpatient cardiac angiography at a later date excluded severe coronary artery disease, thus substantiating the nonischemic nature of the iRVNC.

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with gadobutrol. The red triangle indicates a focused short-axis view of the right ventricle apex, indicating the prominent trabeculae with the interspersed recesses.

Discussion

Ventricular noncompaction is characterized by prominent ventricular trabeculae and deep intertrabecular recesses.2,6 Although it has been categorized as an unclassified cardiomyopathy with a preponderance of left ventricular involvement, the condition is now considered as a distinct but not necessarily pathologic phenotype. Biventricular and isolated right ventricular involvement are noted to be exceedingly rare. 7 VNC is postulated due to genetic and environmental factors leading to the intrauterine arrest of compaction of the loosely interwoven meshwork due to abnormal proliferation, differentiation, and maturation of the fetal myocardial primordium.8,9 There is also emerging evidence for genetic overlap for sarcomeric, cytoskeletal, Z-line, and mitochondrial proteins implicated in the other significant cardiomyopathies. 10 The prevalence of VNC is estimated at 0.014% to 1.3%, with a predilection for Black ethnicity when presenting with heart failure.11,12 It generally is classified as an inherited cardiomyopathy with autosomal dominant inheritance, and clinical screening of first-degree family members is indicated. 13 Genetic studies of LVNC have principally identified cardiomyopathy gene variants, such as MYH7, MYBPC3, and TTN, with genetic testing yields between 17% and 41%. 14

Clinical features include dyspnea (60%), angina (15%), palpitations (18%), syncope or presyncope (9%), prior cerebrovascular event (3%), and severe heart failure (31%). 15 On further questioning, our patient revealed that he experienced many of these symptoms during the preceding 3 years. It has been suggested that VNC may phenotypically develop during adult life during certain conditions such as hypertension. 16 LVNC is increasingly being detected in adults, although the clinical impact of adulthood presentation remains unclear, especially when a familial genetic link is excluded. 17 LV trabeculation identified in such cases may be an incidental finding or a feature of a syndrome. 18 We speculate that the onset of this symptomatology may have coincided with the patient’s diagnosis of hypertension which may have eventually contributed to VNC. It is also biologically plausible that the VNC coexisted coincidentally and may have contributed to the development of his pulmonary hypertension.

Complications include heart failure, arrhythmias, and thromboembolism. The full spectrum of heart failure presentations with preserved, mid-range, and reduced EFs, including index hospitalizations and cardiogenic shock, have been reported. 15 Additionally, there was a mean thromboembolic event of 8%, ranging from 0% to 24%. 15 Patients with stroke had higher rates of hypertension, higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, and atrial fibrillation than patients without stroke. 19 Arrhythmias include non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (33%), sustained ventricular tachycardia (5%), atrial fibrillation (10%), bundle branch blocks, sinus bradycardia, and accessory pathways. 15 Patients with left bundle-branch-block and EF of <35% were at high risk for a significant clinical event. 20 Our patient presented with a mixed picture of both heart failure and symptomatic PE; however, the electrocardiogram was typically reflective of the latter with sinus tachycardia, RBBB, and right axis deviation.

Notably, the patient did not have any diagnosed neoplasia, autoimmune disease, recent surgery, or prolonged immobilization. The PE may have resulted from the elements that comprise Virchow’s triad, which includes hypercoagulability, stasis, and endothelial injury, all possibly attributed to the VNC. 21 On comprehensive, guideline-directed, optimal medical therapy and chronic DOAC, there was the clinical resolution of the PE, which occurred concurrently with normalization of the EF, and the patient did not experience any further symptoms during interval follow-up. There are recommendations that patients with VNC be administered long-term anticoagulation irrespective of ventricular size and function to attenuate thromboembolic events. 22 Based on the apixaban for the Initial Management of Pulmonary Embolism and Deep-Vein Thrombosis as First-Line Therapy (AMPLIFY) trial, which indicated that apixaban was noninferior to conventional therapy with respect to both acute and recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) and associated with less bleeding and included patients with glomerular filtration rate >25 mL/min/1.73 m2, we opted for renally dosed long-term DOAC for both the acute VTE and to mitigate against recurrent VTE. 23

Echocardiography is the imaging modality most commonly used to establish the diagnosis of VNC based on Jenni criteria, which are the most widely accepted and validated criteria. 24 These comprise (1) a myocardial wall consisting of 2 layers, with a maximum ratio of noncompacted to compacted myocardium >2:1; (2) color Doppler evidence of flow within the deep intertrabecular recesses; (3) prominent trabecular meshwork; and (4) a compacted wall thickness ≤8.1 mm. 24 cMRI is often used in a complementary fashion in ambiguous or inconclusive cases. In a small series, it was considered superior and can also provide crucial information such as fibrosis, which may have practical prognostic value. Some studies report relatively high sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 99%, respectively, based on specific criteria.25-27 cCTA is also a potential alternative imaging modality if 2D-TTE or cMRI is unavailable with a noncompacted to a compacted ratio of >2.3 suggestive of LVNC. 28 Ventriculography is rarely reported as a diagnostic tool and, in the case of iRVNC, can show distinctive typical feather-like changes. 29 The presence of RVNC is often difficult to confirm by imaging, and hence in our patient, we opted for the triad of 2D-TTE, cCTA, and cMRI to ascertain the diagnosis. It has been reported that left VNC with RV dysfunction is associated with adverse clinical events. 30

Conclusion

We describe a patient with iRVNC who presented with submassive PE, which was managed with long-term DOAC. The clinician should be aware of iRVNC as a potential etiology of PE and pragmatic utility of DOAC for acute VTE in this setting and to mitigate against recurrent events.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: All available data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Authors Contributions: RVS, RR, SS, VKS, SAP, LP, SR, and NAS all contributed equally in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional and National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: The patient has provided both verbal and written informed consent to have the details of his case published. Institutional approval was not required for publication.

ORCID iD: Naveen Anand Seecheran  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-0181

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-0181

References

- 1. Jamal S, Kichloo A, Akhtar T. Isolated right ventricular non compaction: a very rare genetic cause of cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(suppl 1):3460. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(20)34087-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weiford BC, Subbarao VD, Mulhern KM. Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 2004;109:2965-2971. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000132478.60674.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hruda J, Sobotka-Plojhar MA, Fetter WPF. Transient postnatal heart failure caused by noncompaction of the right ventricular myocardium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2005;26:452-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Açar G, Alizade E, Yazıcıoğlu MV, Bayram Z. A rare unclassified cardiomyopathy: isolated right ventricle noncompaction. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2013;41:267-267. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2013.27095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:270-276. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rigopoulos A, Rizos IK, Aggeli C, et al. Isolated left ventricular noncompaction: an unclassified cardiomyopathy with severe prognosis in adults. Cardiology. 2002;98:25-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hershberger RE, Morales A, Cowan J. Is left ventricular noncompaction a trait, phenotype, or disease? The evidence points to phenotype. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10:e001968. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen H, Zhang W, Li D, Cordes TM, Payne RM, Shou W. Analysis of ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction using genetically engineered mouse models. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30:626-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Monserrat L, Barriales-Villa R, Hermida-Prieto M. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular non-compaction: two faces of the same disease. Heart. 2008;94:1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aras D, Tufekcioglu O, Ergun K, et al. Clinical features of isolated ventricular noncompaction in adults long-term clinical course, echocardiographic properties, and predictors of left ventricular failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:726-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kohli SK, Pantazis AA, Shah JS, et al. Diagnosis of left-ventricular non-compaction in patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction: time for a reappraisal of diagnostic criteria? Eur Heart J. 2008;29:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sasse-Klaassen S, Gerull B, Oechslin E, et al. Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricular myocardium in the adult is an autosomal dominant disorder in the majority of patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;119A:162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Waning JI, Caliskan K, Hoedemaekers YM, et al. Genetics, clinical features, and long-term outcome of noncompaction cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:711-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhatia NL, Tajik AJ, Wilansky S, Steidley DE, Mookadam F. Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricular myocardium in adults: a systematic overview. J Card Fail. 2011;17:771-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arbustini E, Weidemann F, Hall JL. Left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy or a trait shared by different cardiac diseases? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1840-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross SB, Jones K, Blanch B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of left ventricular non-compaction in adults. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1428-1436. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ross SB, Semsarian C. Clinical and genetic complexities of left ventricular noncompaction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:1033-1034. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stöllberger C, Wegner C, Finsterer J. CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc scores and embolic risk in left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Engberding R, Gerecke B. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy, a novel clinical entity (historical perspective). In: K Caliskan, O Soliman, Cate FJ ten, eds. Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy. Springer; 2019:1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bagot CN, Arya R. Virchow and his triad: a question of attribution. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:180-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oechslin EN, Attenhofer Jost CH, Rojas JR, Kaufmann A, Jenni R. Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:493-500. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00755-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jenni R, Oechslin E, Schneider J, Jost CA, Kaufmann PA. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: a step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2001;86:666-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen SE, Selvanayagam JB, Wiesmann F, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stöllberger C, Kopsa W, Tscherney R, Finsterer J. Diagnosing left ventricular noncompaction by echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and its dependency on neuromuscular disorders. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:383-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thuny F, Jacquier A, Jop B, et al. Assessment of left ventricular non-compaction in adults: side-by-side comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with echocardiography. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103:150-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sidhu MS, Uthamalingam S, Ahmed W, et al. Defining left ventricular noncompaction using cardiac computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 2014;29:60-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cao YJ, Zhang X, Qiu BH, et al. Isolated right ventricular noncompaction caused recurrent pulmonary embolism. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15:382-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stacey RB, Andersen M, Haag J, et al. Right ventricular morphology and systolic function in left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1018-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]