Abstract

Purpose

Although usefulness of VISITAG SURPOINT (VS) on pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation has been reported, optimal VS thresholds can depend on the inter‐tag distance (ITD) and vice versa. We validated the efficacy of PVI with lower target ITDs and VS values than in previous studies.

Methods

Retrospective review of consecutive patients (N = 100) with paroxysmal (n = 32) or persistent AF (n = 68) undergoing VS‐guided ablation between 09/2018 and 08/2019 was conducted. All procedures were performed by two operators. Target VS values were 425 (anterior), 375 (posterior), and 325 (near the esophagus). Target ITD was 4 mm.

Results

Acute PVI was achieved in all cases, however, 13 residual gaps in 12 patients were observed after initial encirclement (first pass isolation: 88%). Ten gaps due to spontaneous PV reconnections (PVR) were found in nine patients (9%). These 23 gaps had similar median VS (gap‐related vs non‐gap: 429 vs 410, P = .4545) and power (36 vs 36W, P = .4843), higher contact force (13.8 vs 11.0g, P = .0061), and larger ITD (5.3 vs 3.7mm, P < .001) when compared to the remaining tags. Only ITDs were independently associated with gap formation in multivariate analysis. One‐year Kaplan‐Meier freedom from any atrial arrhythmia was 87.2%. Eight patients received repeat ablation (8.1%) and of these, 6 (75%) were free from PVR.

Conclusion

Favorable rates of first pass isolation, acute PVR, and long‐term procedure success were achieved using lower VS values than in previous reports. With a target VS value of 375‐425, ITDs of 4 mm was sufficient for durable PVI.

Keywords: ablation index, atrial fibrillation, catheter ablation, pulmonary vein isolation, VISITAG SURPOINT

With a target VS value of 375‐425, ITDs of 4 mm was sufficient for durable PVI.

1. INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common form of cardiac arrhythmia. 1 Although radiofrequency (RF) catheter ablation is an established and recommended treatment option for paroxysmal AF (PAF), 2 recovery of ablated tissue and reconnection of at least one pulmonary vein (PV) has been reported in up to 70% of AF patients following pulmonary vein isolation (PVI). 2 , 3 In fact, pulmonary vein reconnection (PVR) has been identified as a major driving factor of AF recurrence, 4 , 5 , 6 which may result in repeat ablations, increased medical costs, 7 and higher risk of complications. 8 Creating durable lesions during PVI is therefore critical to prevent PVR and subsequent recurrence of arrythmia. 2 , 9 , 10

The adoption of real‐time contact force (CF) monitoring in RF catheter ablation has optimized acute and long‐term procedural success by providing operators with information on catheter stability and tissue‐catheter contact. 11 , 12 , 13 However, factors other than CF have been shown to affect lesion formation (eg energy delivery, time, and RF power). 14 VISITAG SURPOINT (VS; previously Ablation Index) is a module available in the CARTO3 System that allows automated annotation and tagging of RF ablation applications. In clinical studies, VS‐guided ablation has demonstrated high durability in PVI and arrhythmia‐free survival up to 12‐14 months after an index ablation procedure. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

Although benchmark studies have reported the safety, efficacy, clinical applicability, and procedural efficiency outcomes associated with the use of VS, 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 these studies have recommended definitive VS thresholds while providing relatively general guidance on the inter‐tag distance (ITD), which is expected to influence lesion contiguity and PVI durability. A recent randomized controlled study reported that lower target ITD was associated with better acute procedural outcomes, suggesting that smaller ITDs may allow for less extensive ablation per lesion. 23 Therefore, the efficacy of PVI with lower target ITD and VS values should be validated. The objective of this single‐center, retrospective, observational study was to examine the clinical outcomes of catheter ablation with lower target ITDs and less intensive ablation at each lesion, along with factors contributing to residual conduction and reconnection gaps, during catheter ablation for AF.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

Inclusion criteria included adult patients (≥18 years of age) with drug‐resistant symptomatic AF (PAF or persistent [PsAF]) who underwent VS‐guided circumferential ipsilateral PVI by two operators at the Sakurabashi Watanabe Hospital in Osaka, Japan from September 1, 2018 to August 1, 2019. Exclusion criteria included subjects with long‐standing PsAF at diagnosis, prior ablation for AF, or those with deterioration of renal function (ie creatine clearance below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Those who received extensive empiric ablation beyond PVI were also excluded to highlight the efficacy of VS‐guided PVI alone. Finally, 100 consecutive subjects who met these criteria were included in this analysis. (Supplementary Figure S1) Patients were maintained on oral anti‐coagulation for at least 1 month prior to ablation. Warfarin was interrupted 1 day before, and resumed on the evening of the procedure. Anti‐arrhythmic drugs (AADs) were stopped at least 5 half‐lives before ablation. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban were omitted only on the morning of the procedure. 24 The study protocol was approved by our institutional ethics committee prior to data collection (Institutional review board ID: 19‐35). Individual patient informed consent was waived and the opt‐out method for patient recruitment was used due to the retrospective study design.

2.2. Ablation procedure

All patients underwent 3D reconstruction of the left atrium (LA) and PV prior to AF ablation via multi‐detector computed tomography (CT) (Brilliance CT 64; Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA). For cardiac catheterization, two decapolar catheters were placed at the coronary sinus and in the superior vena cava and right atrium, respectively. An intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) catheter was inserted into the right atrium via the femoral vein (Soundstar Catheter; Biosense Webster, Inc, Irvine, CA, USA). Three‐dimensional visualization of the LA was achieved using the CARTO3 System with the CartoSound, CartoMerge, 25 and VISITAG SURPOINT modules (Biosense Webster, Inc, Irvine, CA, USA). A single trans‐septal puncture was performed and two long sheaths were introduced (Daig SL0; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) in the LA. Subjects underwent conscious sedation with a combination of bolus thiamylal sodium, pentazocine, and continuous dexmedetomidine hydrochloride. Bi‐level positive airway pressure and an oropharyngeal airway were employed to maintain stable respiration.

Settings for VISITAG were as follows: (a) catheter stability range of motion ≤1.5 mm, (b) catheter stability duration >5 seconds, and (c) CF ≥5g, time ≥25%. Tag size was set to 3 mm in diameter. We targeted VS values of 425 for the anterior wall, 375 for the posterior wall, and 325 in the proximity of the esophagus evaluated by esophagography, attempting to meet or exceed these thresholds at each lesion. The target ITD was <4.0 mm following standard ablation protocols at our institution.

Procedures were performed using a ThermoCool SmartTouch SF ablation catheter and a Lasso‐Nav circular mapping catheter (Biosense Webster, Inc, Irvine, CA, USA). Ipsilateral circumferential PVI was conducted in sinus rhythm except in patients refractory to electrical cardioversion. Radiofrequency energy was delivered via a point‐by‐point approach guided by VS between 30 and 40 Watts. We aborted RF application near the esophagus if the temperature crossed 40°C, as measured with a SensiTherm probe (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA). In these cases however, ablation at the site was re‐applied after the temperature recovered to an acceptable baseline. Isolation (entrance and exit block) was confirmed after a minimum 20‐minute waiting period. If residual potential persisted after first‐pass circumferential PV ablation or reappeared during the procedure, gaps were mapped and ablated. Upon elimination of the PV potential we performed bonus energy delivery on both sides of the successful points. Intravenous adenosine triphosphate (ATP) challenge to trigger dormant conduction was not performed based on our previous study. 26 Atrial flutter (AFL) or atrial tachycardia (AT) induced by burst pacing was managed via linear ablation of the cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI), roof lines, mitral valve isthmus, and focal atrium tachycardia at the operator's discretion.

2.3. Demographic and procedure data

2.3.1. Patient characteristics

Data consisting of age, sex, height, and body weight were collected at baseline. Additional variables included medication use (anti‐coagulation, beta‐blocker, and AADs), prior cardiovascular events (ie transient ischemic attack [TIA], myocardial infarction [MI], and stroke), comorbidities, and CHA2DS2‐VASc scores. Left atrial volume (LAV), left atrium diameter (LAD), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were recorded based on cardiac CT records.

2.3.2. Procedure and ablation lesion data

Date of admission and discharge, ablation performed (ie PVI, CTI, linear, and others), electrophysiology (EP) lab time (ie from patient entrance to exit), ablation time, RF duration, fluoroscopy time, and fluoroscopy dose were analyzed to describe the index procedure characteristics.

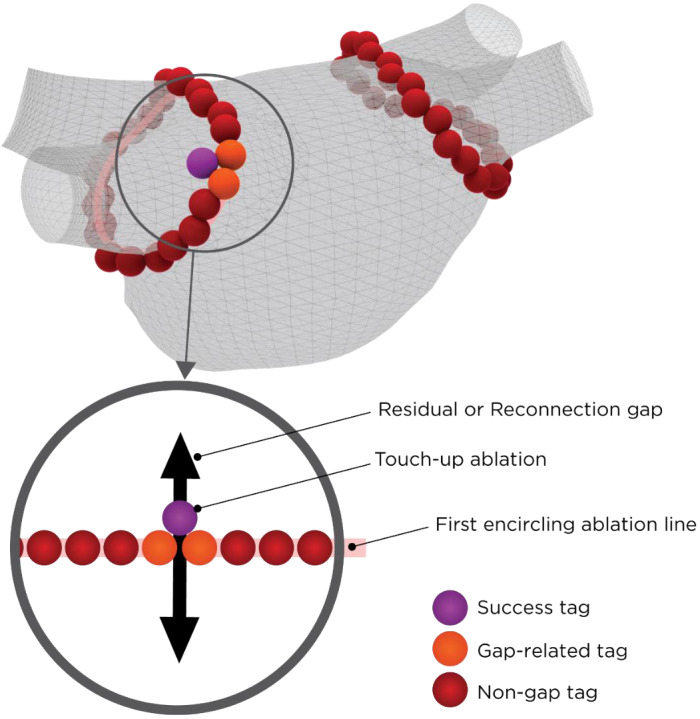

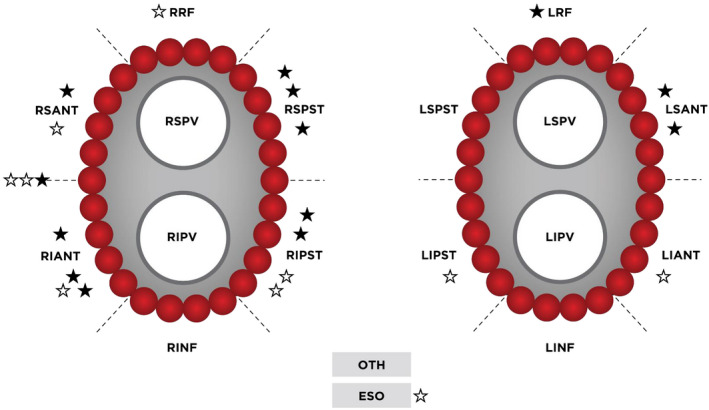

For VS data, we divided conduction gaps into “residual gaps” and “reconnection gaps” based on their timing and characteristics. Pulmonary vein electrical conduction remaining after an initial anatomical burn was referred to as a “residual gap”. Acute reconnections (whether located at residual gaps or elsewhere) detected during the rest of the procedure were named as a “reconnection gaps.” Where additional RF energy was applied for touch‐up, “success tags” were assigned to the last tag where local PV potential was confirmed to have disappeared. The two adjacent tags associated with the success tags were termed “gap‐related tags.” The remaining tags from the first encirclement were referred to as “non‐gap tags.” These definitions are shown in Figure 1. Each PV was divided into six segments (ie roof, superior anterior, inferior anterior, superior posterior, inferior posterior, and inferior) for subsequent analyses. Including two additional areas near the esophagus and otherwise unclassified regions, a total of 14 segments were assigned by CARTO operators (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Gap and Tag Definitions. During the ablation procedure, “success tags” (purple) were associated with lesions where additional RF energy delivery terminated dormant conduction of residual or reconnection gaps (black arrow). The two tags immediately adjacent to both side of the gap were subsequently termed “gap‐related tags” (orange). All remaining tags from the first encirclement (pink line) were referred to as “non‐gap tags” (red)

FIGURE 2.

Segments of Conduction Gaps Observed During the Index Procedure. Black stars indicate segments with residual gaps after the first encirclement. White stars indicate segments with spontaneous reconnection gaps. Abbreviations: LRF, left roof; LSPST, left superior posterior; LIPST, left inferior posterior; LINF, left inferior; LIANT, left anterior; LSANT, left superior anterior; LSPV, left superior pulmonary vein; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; RRF, right roof; RSPST, right superior posterior; RIPST, right inferior posterior; RINF, right inferior; RIANT, right anterior; RSANT, right superior anterior; RSPV, right superior pulmonary vein; RIPV, right inferior pulmonary vein; OTH, other; ESO, esophagus

2.4. Long‐term follow‐up

All patients were hospitalized under continuous rhythm monitoring for 3 days after the ablation procedure. We directed patients to check their heart rate and rhythm at least 3 times per day during post‐ablation follow‐up, and to visit the outpatient clinic if they experienced a relapse. All patients were scheduled for routine follow‐up visits to the outpatient clinic at 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Electrocardiograms were obtained at each visit. A Holter electrocardiogram was performed at the 6‐month visit. Additional monitoring was performed on the basis of symptoms. A 3‐month blanking period was used. Freedom from atrial arrhythmias was defined as the absence of AF, AFL, or AT lasting ≥30 seconds either on or off AADs.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Frequency counts and proportions are provided for binary and categorical data. Continuous variables were reported either as mean ±standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) depending on Normality testing. For continuous variables, comparisons between independent groups were performed using a two sample Student's t test if normally distributed, or the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Mann‐Whitney U test) otherwise. The Chi‐Square test was used for binary and categorical variables. A P‐value <.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Binomial and multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine covariates that may affect outcomes. Covariates were selected based on clinical knowledge and included the patient sex, AF type, AAD use at baseline, exact CHA2DS2‐VASc score, CHA2DS2‐VASc score ≥2 vs 0 or 1, hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease, PVI only vs additional ablation strategies, and VS parameters. All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 3.6.3, The R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient population

The study population comprised 100 patients with a primary diagnosis of PAF (n = 32) or PsAF (n = 68). Demographic and baseline data are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 67 (IQR: 59, 74) years. A majority of patients were male (76%). The most common comorbidities were hypertension (59%) and diabetes mellitus (22%). Most subjects (64%) had a CHA2DS2‐VASc score above 2.

TABLE 1.

Patient and procedural characteristics

|

Total N = 100 |

|

|---|---|

| Age, (median [IQR], years) | 67 (59, 74) |

| Height (mean [SD], cm) | 165.1 (8.9) |

| Weight (median [IQR], kg) | 65.7 (58.7, 73.6) |

| Sex (n [%], male) | 76 (76) |

| AF type (n [%]) | |

| Paroxysmal AF | 32 (32) |

| Persistent AF | 68 (68) |

| Medication (n [%]) | |

| AAD | 50 (50) |

| Anticoagulation | 100 (100) |

| Beta‐blocker | 49 (49) |

| Prior CV events (n [%]) | |

| TIA | 3 (3) |

| MI | 4 (4) |

| Stroke | 9 (9) |

| Comorbidities (n [%]) | |

| Hypertension | 59 (59) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (22) |

| Heart failure | 16 (16) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (11) |

| Valvular disease | 9 (9) |

| Thyroid disease | 9 (9) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 4 (4) |

| Congenital heart disease | 1 (1) |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score (median, IQR) | 2 (1, 3) |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score (n [%]) | |

| 0 | 12 (12) |

| 1 | 24 (24) |

| ≥2 | 64 (64) |

| Left atrial volume (mean [SD], mL) | 56.5 (18.0) |

| Left atrial diameter (mean [SD], mm) | 41.3 (5.6) |

| LVEF (median [IQR], %) | 63 (54, 68) |

| Ablation targets in addition to PVI (n [%]) | |

| CTI | 31 (31.0) |

| Linear | 10 (10.0) |

| Other | 4 (4.0) |

|

EP lab time (median [IQR], minutes) |

145.3 (130.9, 163.1) |

|

Fluoroscopy time (median [IQR], minutes) |

7.2 (4.4, 9.7) |

|

Fluoroscopy dose (median [IQR], mGy) |

17.5 (8.8, 42.0) |

Abbreviations: AAD, antiarrhythmic drug; CFAE, complex fractionated atrial electrogram; CHA2DS2‐VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke or transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, sex category; CI, confidence interval; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; EP, electrophysiology; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; PsAF, persistent atrial fibrillation; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

3.2. Procedural characteristics

In addition to PVI, 31% and 10% of patients received CTI and linear ablation, respectively, due to clinical ATs or arrhythmias induced by burst pacing; 4% were ablated at superior vena cava triggers initiating AF (n = 2) and non‐PV foci for ATs (n = 1), and for premature atrial contractions (n = 1). Median time in the EP lab was 145.3 (130.9, 163.1) minutes. The median fluoroscopy time and dose were 7.2 (4.4, 9.7) minutes and 17.5 (8.8, 42.0) mGy. Total RF application time was 27.3 (23.8, 31.0) minutes.

3.3. Acute clinical outcomes

First pass isolation (FPI) was accomplished in both ipsilateral PVs for 88 patients (88%), with 13 gaps remaining after the first encirclement. Nine patients (9%) experienced spontaneous PVR due to 10 reconduction gaps. Since two patients had both residual and reconnection gaps (Supplementary Table S1), 81 were free from any PVI gaps prior to touch‐up. Acute procedural success was achieved in 100% of patients. No major adverse events (AEs) occurred in the periprocedural period. One right femoral arteriovenous fistula was observed; ultrasound‐guided compression was effective to occlude it. Four acute gastric dilatations were detected; all of them received linear ablation across the esophagus for PVI and spontaneously recovered after 2‐5 days. None required surgery or intervention, and all complications resolved without permanent clinical sequelae. Binomial and multiple regression analyses showed no significance of covariates on any acute clinical outcomes (FPI, PVR, or acute success).

3.4. VS parameter analysis

A total of 7,399 tags were recorded during the procedures. VS parameters stratified by segment are presented in Table 2. Although a substantial number of tags did not strictly satisfy their segment‐specific VS threshold values (anterior: 26.9%, posterior: 37.1%, and near esophagus: 64.3%), deviations remained fairly minimal: 434 (419, 441) in the anterior (target = 425), 384 (337, 403) in the posterior (target = 375), and 303 (269, 332) near the esophagus (target = 325). ITDs were consistently below 4.0 mm in all segments except near the esophagus.

TABLE 2.

Summary of VS ablation parameters by segment. a

| Parameter | Anterior | Posterior | Roof | Inferior | Esophagus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tags (n, [%]) |

3,011 (40.7%) |

2,357 (31.9%) |

1,040 (14.1%) |

709 (9.6%) |

237 (3.2%) |

|

RF application (median [IQR], sec) |

18.6 (14.2, 22.8) |

15.5 (11.2, 20.1) |

18.1 (12.9, 22.8) |

16.2 (12.4, 20.1) |

10.6 (7.6, 14.6) |

|

CF (median [IQR], gram) |

11.3 (8.6, 15.1) |

10.6 (8.3, 14.0) |

11.1 (8.8, 14.0) |

11.6 (8.9, 15.5) |

10.2 (7.7, 14.1) |

|

Power (median [IQR], W) |

36.1 (36.0, 40.4) |

35.9 (30.9, 36.1) |

36.0 (35.9, 36.3) |

36.0 (31.1, 36.1) |

30.8 (25.9, 31.0) |

|

Impedance drop (median [IQR], Ω) |

9.2 (6.3, 12.6) |

7.6 (5.1, 10.6) |

9.0 (6.2, 12.7) |

9.3 (6.8, 12.2) |

8.8 (6.7, 11.3) |

|

Actual VS (median [IQR]) |

434 (419, 441) |

384 (337, 403) |

429 (382, 436) |

397 (364, 433) |

303 (269, 332) |

|

ITD (median [IQR], mm) |

3.7 (2.8, 4.6) |

3.7 (2.9, 4.6) |

3.6 (2.7, 4.6) |

3.8 (2.9, 4.8) |

4.4 (3.4, 6.0) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; RF, radiofrequency; VS, VISITAG SURPOINT; W, watts; CF, contact force; ITD, inter‐tag distance.

35 tags were missing segment assignment and are not included in the table.

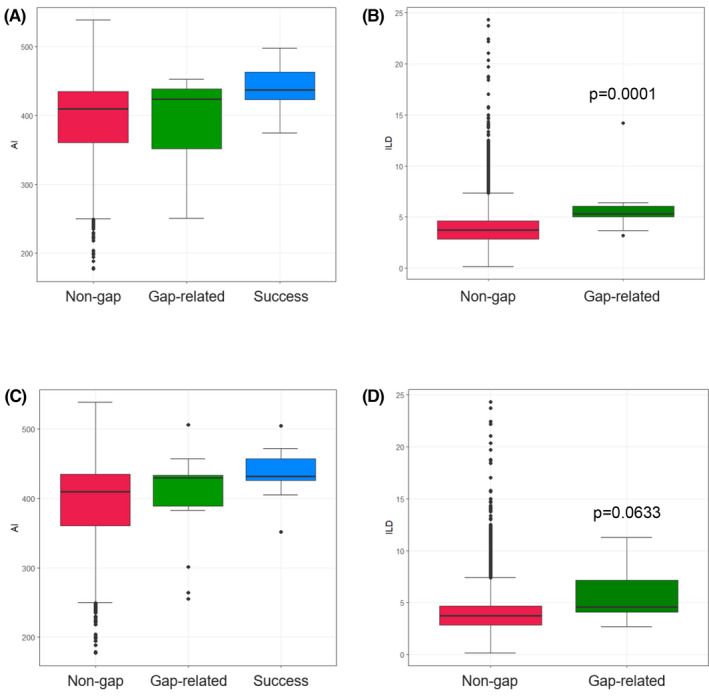

3.5. Residual Gaps

Thirteen residual gaps occurred in 12 patients and were successfully isolated with additional RF applications. These were most commonly observed in the anterior (7/13, 53.8%) as opposed to the posterior (5/13, 38.5%) and roof (1/13, 7.7%) segments (Figure 2). Figure 3A and 3B depict the box plots for VS values and ITDs based on tag classifications (ie non‐gap, gap‐related, and success). As shown in panel A, there was no difference in the median VS values between gap‐related and non‐gap tags (424 [352, 439] vs 410 [361, 435], P = .8262). VISITAG SURPOINT values (437 ± 38) beyond the anterior segment target were applied to achieve successful elimination of residual gaps. On ITD, ablation tags contributing to residual gaps were found to be statistically longer (5.3 [5.0, 6.1] vs 3.7 [2.8, 4.7] mm, P < .001).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of VS Values and ITDs based on Gap Classifications VS values (A) and ITDs (B) based on residual gap classifications. (C) VS values and (D) ITDs based on reconnection gap classifications. Abbreviations: VS, VISITAG SURPOINT; ITD, inter‐tag distance

3.6. Reconnection Gaps

Ten spontaneous reconnections occurred in nine patients and were terminated with additional RF applications. These were most commonly observed in the anterior (6/10, 60.0%) vs the posterior (2/10, 20.0%), roof (1/10, 10.0%), or near the esophagus (1/10, 10.0%) segments. Figure 3C and 3D depict the box plot for VS values and ITDs based on tag classifications (ie non‐gap, gap‐related, and success). Similar to the residual gap analysis, there was no difference between median VS values for reconnection vs non‐reconnection tags (430 [389, 434] vs 410 [361, 435], P = .3842). A high VS value (436 ± 41) applied to reconduction sites resulted in successful elimination of these gaps. On ITD, ablation tags contributing to reconnections were also statistically longer (4.6 [4.1, 7.1] vs 3.7 [2.8, 4.7] mm, P = .0141).

3.7. Features of gap‐related tags and non‐gap tags

A total of 23 gaps (13 residual gaps and 10 reconnection gaps) were observed in 19 patients (Supplementary Table S1), and therefore 46 gap‐related, 23 success, and 7,330 non‐gap tags were identified in this study. Gaps were found more commonly in the right versus the left PV (residual gaps: right = 8, left = 5; reconnection gaps: right = 7, left = 2). One reconnection gap was observed near the esophagus. Four gaps were located in the carina, 1 of which was a residual gap and 3 of which were reconnection gaps. Table 3 illustrates that the median VS value of non‐gap tags were similar to that of gap‐related tags (410 [361, 435] vs 429 [384, 435], P = .4545). ITD was significantly longer among gap‐related tags (median: 5.3 [4.3, 6.3] vs 3.7 [2.8, 4.7] mm, P < .001). CF was also significantly associated with gap‐related tags. However, multivariate logistic analysis revealed that ITD was the only independent variable associated with gap‐related tags, and the odds ratio for gap formation with ITD ≥4 mm was 6.6051 (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 2.2444‐19.4387) compared with ITD <4 mm (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of VS parameters for gap‐related vs all other tags

| Parameter (median [IQR]) |

Gap‐Related Tags (N = 46) |

Other Tags a (N = 7,330) |

P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF application (sec) | 16.1 (11.2, 19.7) | 17.1 (12.2, 21.7) | 0.2599 |

| CF (gram) | 13.8 (10.0, 16.2) | 11.0 (8.5, 14.7) | 0.0061 |

| Power (W) | 36.0 (35.9, 36.2) | 36.0 (35.8, 36.3) | 0.4843 |

| Impedance drop (Ω) | 8.2 (6.1, 12.2) | 8.6 (5.9, 11.9) | 0.9133 |

| Actual VS | 429 (384, 435) | 410 (361, 435) | 0.4545 |

| ITD (mm) | 5.3 (4.3, 6.3) | 3.7 (2.8, 4.7) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CF, contact force; IQR, interquartile range; ITD, inter‐tag distance; RF, radiofrequency; VS, VISITAG SURPOINT; W, watts.

Other Tags, All tags from the first encirclement, excluding gap‐related and success tags.

TABLE 4.

Multivariate logistic analysis to predict gap formation

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|

OR (95% CI) |

P‐value |

OR (95% CI) |

P‐value |

OR (95% CI) |

P‐value | |

| RF application (per 10 sec increase) |

0.7428 (0.4704‐1.1730) |

0.2021 | ||||

| CF (per 10 gram increase) |

1.5641 (1.0070‐2.4295) |

0.0465 |

1.5609 (0.8608‐2.8303) |

0.1425 |

1.6633 (0.9287‐2.9788) |

0.0870 |

| Power (per 10 W increase) |

1.9603 (0.7735‐4.9680) |

0.1560 | ||||

| Impedance drop (per 10 Ω decrease) |

0.7543 (0.4349‐1.3081) |

0.3155 | ||||

| Actual VS (per 10‐unit increase) |

1.0169 (0.9664‐1.0701) |

0.5181 | ||||

| ITD (per 1 mm increase) |

1.2564 (1.1455‐1.3780) |

<0.0001 |

1.2467 (1.1354‐1.3688) |

<0.0001 | ||

| ITD (<4 mm [reference] vs ≥4mm) |

6.6208 (2.2501‐19.4813) |

0.0006 |

6.6051 (2.2444‐19.4387) |

0.0006 | ||

Multivariate logistic regression included variables with a p value <0.10 in univariate analysis. Model 1 was performed with ITD in 1 mm increments, while Model 2 divided data into those meeting the target ITD (reference) vs those that did not.

Abbreviations: CF, contact force; CI, confidence interval; ITD, inter‐tag distance; OR, odds ratio; RF, radiofrequency; VS, VISITAG SURPOINT; W, watts.

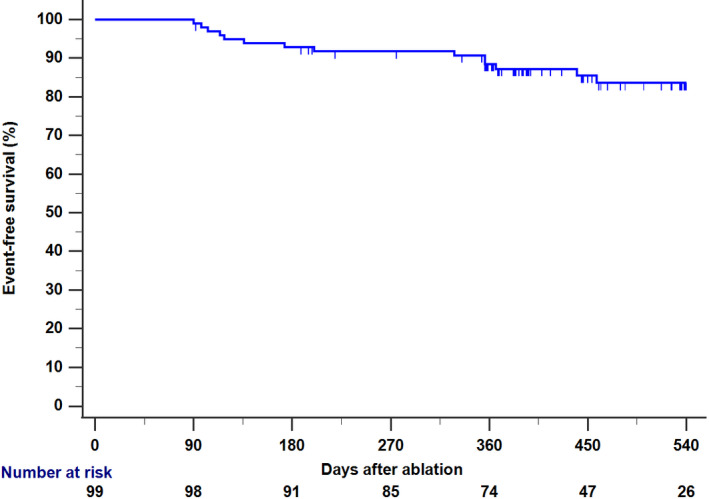

3.8. Long‐term clinical outcomes

We obtained follow‐up data for 99 patients at a median follow‐up duration of 462 ± 110 days. Eighty‐four (84.8%) were free from any atrial tachyarrhythmias based on standard‐of‐care monitoring. At 1‐year, the Kaplan‐Meier survival from AT/AF was 87.2% (95% CI: 80.4%–94.0%) (Figure 4). The recurrence‐free rate at 1‐year was similar between patients with paroxysmal AF and those with persistent AF (86.9% vs 89.2%, P = .7079). There was no significant difference between patients on the recurrence‐free rate based on the presence or absence of gaps (with vs without: 94.7% vs 82.5%, P = .2901). Because 21 patients (21%) remained on anti‐arrhythmic drugs after the blanking period, we also performed a comparison between patients who stopped AADs and those who continued. Recurrence‐free rate tended to be higher in the former group (off‐AAD vs on‐AAD: 90.6% vs 80.0%, P = .1344). Eight patients (8.1%) received re‐ablation at a median 239 ± 141 days after the index procedure. Among these, 75.0% (6/8) of patients and 84.4% (27/32) of PVs remained fully isolated. No procedure‐related AEs were reported in any patients.

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan‐Meier Curve for Recurrence of AT/AF after the Index Procedure During median follow‐up of 462 days (N = 99), AT/AF recurrence was observed in 15 (15.2%) patients. Abbreviations: AT, atrial tachycardia; AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval

4. DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates safe and effective AF ablation at lower target ITD and VS values than commonly reported, with a high FPI (88%), low acute PVR (9%), durable lesions (84% PVs isolated), and high one‐year procedural success (87%). Our results suggest that beyond VS thresholds, ITD is an important determinant of procedural success due to its impact on lesion contiguity. Durable PVI is critical to prevent late tissue recovery and arrhythmia recurrence; therefore, these findings help inform best practice in a real‐world clinical setting.

The safety, efficacy, clinical applicability, and procedural efficiency outcomes associated with VS‐guided AF ablation have previously been reported in benchmark studies. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Specifically, the CLOSE protocol described low rates of PVR and promising long‐term success using an ITD ≤6 mm and target VS of 550/400 at the anterior/posterior walls. 20 VISTAX was the first multi‐center study exploring reproducibility of the CLOSE protocol for 340 patients with PAF, and reported an 82.4% FPI rate and 12‐month freedom from AT/AF of 89.4% across 17 sites. 15

Our protocol adopted a target ITD of 4 mm and target VS of 425/375 at the anterior/posterior walls, which were lower than those in the CLOSE protocol. Ablating with a high VS value may achieve large lesions. However since tissue damage increases, the risk of collateral damage and complications such as tamponade may commensurately increase. The concept of our setting is to create durable lesions by ablating more densely while ensuring a reliable burn with strict catheter stability at each site. Operators may face some technical difficulties in implementing this strategy due to the stringent stability requirement. On the other hand, even with more ablation sites, the overall procedure time should not change much as it takes less time per lesion to reach the lower target VS values.

One‐year Kaplan‐Meier freedom from recurrence was 87.2% in our study. This value appears slightly low compared with single center reports of up to 94% freedom from atrial arrhythmias 18 in PAF ablation. Nevertheless, our findings may be reasonable because two‐thirds of the study population consisted of persistent AF patients, where outcomes are generally worse than in PAF. 27 Despite lower target ITD and VS, consistent results compared with VISTAX indicate that our protocol is also sufficient to obtain reasonable clinical outcomes. Although discontinuation of AADs within the blanking period is generally recommended in this study, medical rhythm control therapy was continued in 21 patients at the discretion of the attending doctors. Interestingly, recurrence‐free rate tended to be higher in patients off‐AAD than those on‐AADs, but this might be reasonable because AADs would be continued in patients considered to be at high risk of recurrence.

Relatively few studies have described the use of lower VS values. 28 , 29 In the OPTIMUM study, Lee et al evaluated the optimal VS values for avoiding acute PVR and examined the feasibility and efficacy of these targets among a Korean population. 30 Authors found that VS values ≥450 for the anterior/roof segments, ≥350 for the posterior/inferior/carina segments, and an ITD of ≤4 mm decreased acute PVR compared to conventional PVI ablation without the use of VS. Okamatsu et al investigated the role of power on VS‐guided ablation using a target VS of 400 for the anterior, 360 for the posterior, and 260 for the oesophagus. 31 Results suggested lower VS settings may be effective in creating durable lesions regardless of RF power.

We also investigated various VS parameters to elucidate the correlation between ablation settings and conduction gaps. In multivariable analysis most covariates were not independently associated with gap formation, though contact force approached significance. On the contrary, ITD ≥4 mm demonstrated a strong risk for residual conduction and reconnections (OR: 6.6051, 95% CI 2.2444‐19.4387). Our mean ITD for gap‐related tags was 5.3 mm, which is within the range advised by the CLOSE protocol. Hoffman et al very recently recommended to aim for ITD of 3.0–4.0 mm, rather than 5.0–6.0 mm, to optimize FPI based on results of a randomized controlled trial. 23 These data highlight that optimal VS thresholds can vary depending on ITDs and vice versa. Closer ITDs may permit less extensive ablation per lesion.

In this study, a total of 23 gaps were observed during the procedure and 9 of them (39%) were located on the anterior wall of the RPV. An epicardial connection between the RPV and the RA sometimes precludes PVI and may resemble a conduction gap. The frequency of gaps here was lower than the reported rate of epicardial connections. 32 , 33 This discrepancy may indicate that some epicardial connections may have been successfully ablated by VS‐based PVI, that is, with a line on the anterior‐side of the RPV which is relatively proximal to PVs, or that the frequency of epicardial connection have been overestimated. The usefulness of unipolar signal modification (USM) has also been published recently. 34 Although it may be difficult to identify potentials of epicardial connections, a combination of these two methods may be useful to achieve PVI without gaps. Finally, it was somewhat surprising that the presence or absence of gaps during the index procedure was not associated with the recurrence of AT/AF, possibly because all gaps were ablated carefully and intensively. In our series, 84% of PVs remained isolated in patients who received repeat ablation. Thus, VS‐guided PVI performed under the described settings appears durable with re‐ablations caused primarily by non‐PV mechanisms.

4.1. Limitations

There are a few limitations to this study. First, it was retrospective, observational, and without randomization. In addition, patients who underwent empiric extensive ablation were excluded to highlight the effectiveness of VS‐based PVI. Therefore, selection bias could not be controlled. Second, during the follow‐up period, patients received limited assessment of recurrence. Freedom from atrial arrhythmias might have been overestimated accordingly in case of asymptomatic AT/AF. Third, while the participants in prior benchmark studies were mainly Caucasian, 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 all our study subjects were Asian. Because anatomic sizing and features in Asians are typically smaller, this might have impacted outcomes. Fourth, an adequate VS setting should be one where durable PVI can be achieved without the impact of latent heat from prior RF application. However, we did not have data on the time interval between each RF application so could not exclude it in this study. Finally, results are limited to a single center with two operators. The study may not be generalizable if material changes in ablation workflows, hospital practice patterns, or VS protocols are applied elsewhere.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Favorable rates of FPI, acute PVR, and long‐term procedure success were achieved with VS‐guided AF catheter ablation at lower target ITD and VS values than previously reported. Gap characterization showed that ITD was significantly associated with the presence of residual conduction and reconnection sites. With a target VS value of 375‐425, ITDs of 4 mm was sufficient for durable PVI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Koichi Inoue is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson. The other authors have nothing to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Koichi Inoue. Collection and assembly of data: Koichi Inoue, Nobuaki Tanaka, Yusuke Ikada, Akihiro Mizutani, Kazuhiko Yamamoto, Hana Matsuhira, Shinichi Harada. Data analysis and interpretation: All authors. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Institutional review board ID is 19‐35.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S2

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing services were provided by Susan Bartko‐Winters, PhD, from SBW Medical Writing Inc The authors thank Yoko Ichishima for assistance with tag data extraction, Hye Jin Park, MPH, for biostatistics support, and Stephanie Lee, PhD, for manuscript editing.

Inoue K, Tanaka N, Ikada Y, et al. Characterizing clinical outcomes and factors associated with conduction gaps in VISITAG SURPOINT‐guided catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Arrhythmia. 2021;37:574–583. 10.1002/joa3.12544

Funding information

This research was conducted with support from the Collaboration Study Program (BWI‐CS‐005) of Biosense Webster, Inc Medical writing services were funded by Johnson & Johnson.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [KI], upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bai Y, Wang YL, Shantsila A, Lip GYH. The global burden of atrial fibrillation and stroke: a systematic review of the clinical epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in Asia. Chest. 2017;152:810–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow‐up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:632 e621–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kuck KH, Brugada J, Furnkranz A, et al. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cappato R, Negroni S, Pecora D, et al. Prospective assessment of late conduction recurrence across radiofrequency lesions producing electrical disconnection at the pulmonary vein ostium in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:1599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nanthakumar K, Plumb VJ, Epstein AE, Veenhuyzen GD, Link D, Kay GN. Resumption of electrical conduction in previously isolated pulmonary veins: rationale for a different strategy? Circulation. 2004;109:1226–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ouyang F, Tilz R, Chun J, et al. Long‐term results of catheter ablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: lessons from a 5‐year follow‐up. Circulation. 2010;122:2368–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mansour M, Karst E, Heist EK, et al. The impact of first procedure success rate on the economics of atrial fibrillation ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Szegedi N, Szeplaki G, Herczeg S, et al. Repeat procedure is a new independent predictor of complications of atrial fibrillation ablation. Europace. 2019;21:732–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, et al. Worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:1100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neuzil P, Reddy VY, Kautzner J, et al. Electrical reconnection after pulmonary vein isolation is contingent on contact force during initial treatment: results from the EFFICAS I study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Macle L, Frame D, Gache LM, Monir G, Pollak SJ, Boo LM. Atrial fibrillation ablation with a spring sensor‐irrigated contact force‐sensing catheter compared with other ablation catheters: systematic literature review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e023775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Natale A, Reddy VY, Monir G, et al. Paroxysmal AF catheter ablation with a contact force sensing catheter: results of the prospective, multicenter SMART‐AF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reddy VY, Pollak S, Lindsay BD, et al. Relationship between catheter stability and 12‐month success after pulmonary vein isolation: a subanalysis of the SMART‐AF Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;2:691–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haines DE. Determinants of lesion size during radiofrequency catheter ablation: the role of electrode‐tissue contact pressure and duration of energy delivery. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1991;2:509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duytschaever M, Vigen J, De Potter T, et al. Standardized pulmonary vein isolation workflow to enclose veins with contiguous lesions: the multicentre VISTAX trial. Europace. 2020;22:1645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dhillon G, Ahsan S, Honarbakhsh S, et al. A multicentered evaluation of ablation at higher power guided by ablation index: establishing ablation targets for pulmonary vein isolation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30:357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hussein A, Das M, Riva S, et al. Use of ablation index‐guided ablation results in high rates of durable pulmonary vein isolation and freedom from arrhythmia in persistent atrial fibrillation patients: the PRAISE Study Results. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11:e006576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phlips T, Taghji P, El Haddad M, et al. Improving procedural and one‐year outcome after contact force‐guided pulmonary vein isolation: the role of interlesion distance, ablation index, and contact force variability in the 'CLOSE'‐protocol. Europace. 2018;20:f419–f427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Solimene F, Schillaci V, Shopova G, et al. Safety and efficacy of atrial fibrillation ablation guided by Ablation Index module. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2019;54:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taghji P, El Haddad M, Phlips T, et al. Evaluation of a strategy aiming to enclose the pulmonary veins with contiguous and optimized radiofrequency lesions in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a pilot study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Das M, Loveday JJ, Wynn GJ, et al. Ablation index, a novel marker of ablation lesion quality: prediction of pulmonary vein reconnection at repeat electrophysiology study and regional differences in target values. Europace. 2017;19:775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Munkler P, Kroger S, Liosis S, et al. Ablation index for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation‐ clinical applicability and comparison with force‐time integral. Circ J. 2018;82:2722–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffmann P, Ramirez ID, Baldenhofer G, Stangl K, Mont L, Althoff T. Randomized study defining the optimum target interlesion distance in ablation index‐guided atrial fibrillation ablation. Europace. 2020;22:1480–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tanaka N, Inoue K, Tanaka K, et al. Automated ablation annotation algorithm reduces re‐conduction of isolated pulmonary vein and improves outcome after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circ J. 2017;81:1596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inoue K. CartoMerge using soundStar catheter and time force integral‐based ablation for atrial fibrillation. Int J Arrhythm. 2017;18:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kobori A, Shizuta S, Inoue K, et al. Adenosine triphosphate‐guided pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation: the UNmasking Dormant Electrical Reconduction by Adenosine TriPhosphate (UNDER‐ATP) trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3276–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamaguchi J, Takahashi Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Clinical outcome of pulmonary vein isolation alone ablation strategy using VISITAG SURPOINT in non‐paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:2592–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kobayashi S, Fukaya H, Oikawa J, et al. Optimal interlesion distance in ablation index‐guided pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020. Online ahead of print. 10.1007/s10840-020-00881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yazaki K, Ejima K, Higuchi S, Yagishita D, Shoda M, Hagiwara N. Regional differences in the effects of ablation index and interlesion distance on acute electrical reconnections after pulmonary vein isolation. Journal of Arrhythmia. 2020;00:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee SR, Choi EK, Lee EJ, Choe WS, Cha MJ, Oh S. Efficacy of the optimal ablation index‐targeted strategy for pulmonary vein isolation in patients with atrial fibrillation: the OPTIMUM study results. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2019;55:171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okamatsu H, Koyama J, Sakai Y, et al. High‐power application is associated with shorter procedure time and higher rate of first‐pass pulmonary vein isolation in ablation index‐guided atrial fibrillation ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30:2751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barrio‐Lopez MT, Sanchez‐Quintana D, Garcia‐Martinez J, et al. Epicardial connections involving pulmonary veins. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e007544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yoshida K, Baba M, Shinoda Y, et al. Epicardial connection between the right‐sided pulmonary venous carina and the right atrium in patients with atrial fibrillation: a possible mechanism of preclusion of pulmonary vein isolation without carina ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:671–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ejima K, Kato K, Okada A, et al. Comparison between contact force monitoring and unipolar signal modification as a guide for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: prospective multi‐center randomized study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019;12:e007311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S2

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [KI], upon reasonable request.