Abstract

Background:

Incidences of subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) related systemic reactions (SRs) and fatal reactions (FRs) are not well defined, nor are delayed-onset SRs and their treatment.

Objectives:

To estimate SCIT-related SRs/FRs, and the incidence and treatment of delayed-onset SRs.

Methods:

In 2008 and 2009, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) and American College of Allergy Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) members completed a survey about SCIT-related SR severity (grade 1 = mild; grade 2 = moderate; grade 3 = severe anaphylaxis). In 2009, members reported the time of onset and use of epinephrine (EPI), with early onset defined as beginning ≤30 minutes, and delayed onset beginning more than 30 minutes after injections.

Results:

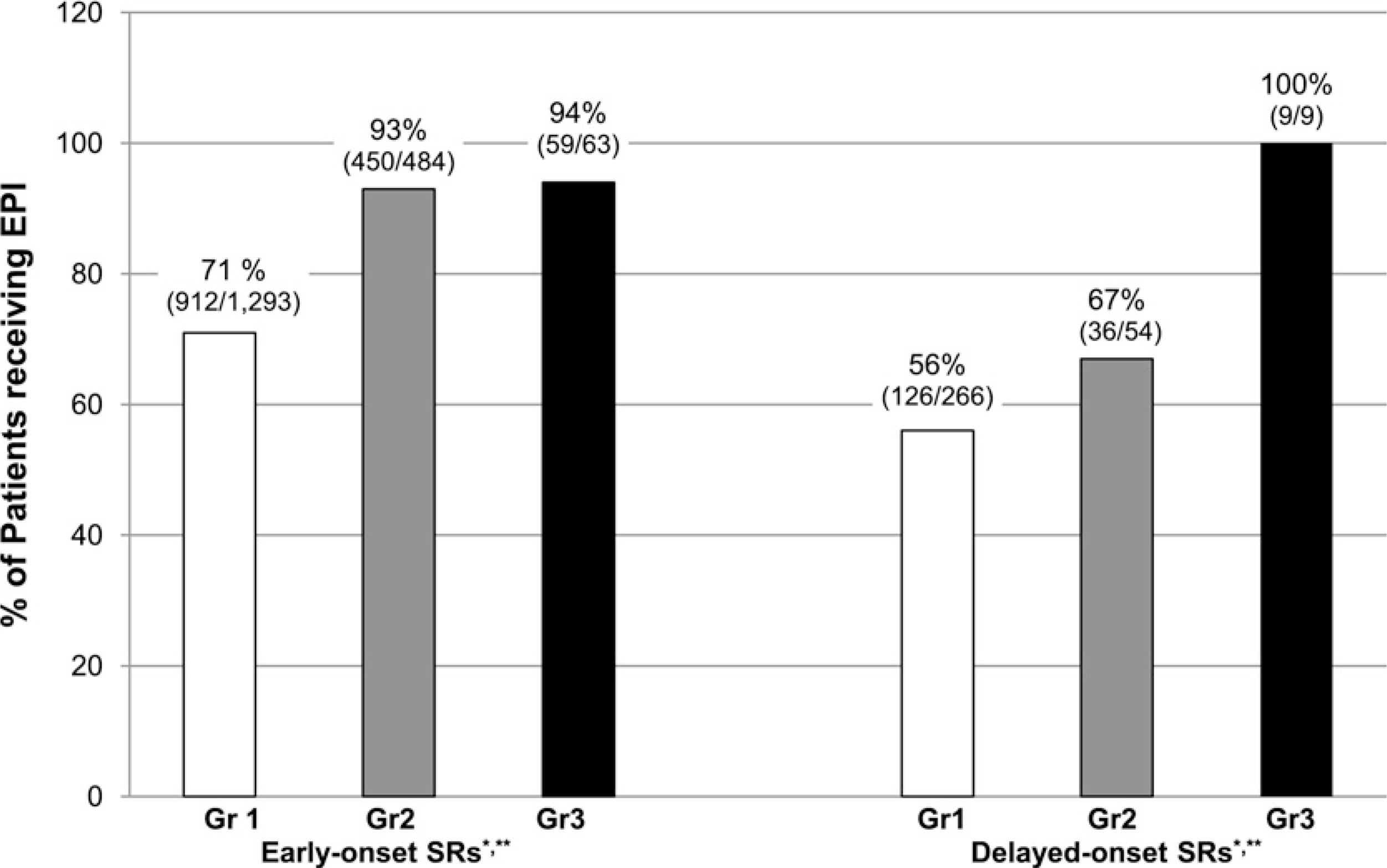

As in year 1, no FRs were reported during year 2 (630 total practices responded). Among 267 practices providing data on the timing of SRs, 1,816 early-onset SRs (86%) and 289 (14%) delayed-onset SRs were reported. Fifteen percent (226/1,519) of grade 1, 10% (54/538) of grade 2, and 12.5% (9/72) of grade 3 SRs were delayed-onset. Among early-onset SRs, EPI was given for 71% of grade 1, 93% of grade 2, and 94% of grade 3s. Among delayed-onset SRs, EPI was given for 56% of grade 1, 67% of grade 2, and 100% of grade 3s (P = .0008 for difference in EPI administration based on severity; P = .07 based on time of onset).

Conclusions:

Delayed-onset SRs are less frequent than previously reported. Epinephrine was given less frequently for grades 1 and 2 (but not grade 3) delayed-onset SRs compared with early-onset SRs. Further study of prescribing self-injectable EPI for SCIT patients in the event of delayed-onset SRs may be warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy (SCIT) is effective in treating allergic rhinitis and asthma and in preventing stinging insect anaphylaxis. The benefits of SCIT have been tempered by the rare occurrence of near-fatal and fatal reactions (FRs) after injections.1–6 Based on retrospective surveys of members of the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) conducted before 2002, a fatal anaphylactic reaction to SCIT was estimated to occur in every 2 to 2.5 million injections, or 3.4 SCIT-related deaths per year. Near-fatal reactions to SCIT, which were previously defined as severe respiratory compromise or hypotension, occurred after every 1 million injections (4.7 near-fatal reactions per year).7, 8 In 2008, a web-based surveillance program was initiated among members of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) and AAAAI to monitor annual incidences of FRs related to allergen skin testing and SCIT as well as nonfatal systemic reactions (SRs) to SCIT.9

Before launching this surveillance program in 2008, 6 SCIT fatalities were retrospectively reported that transpired between 2001 and 2007 and since the last published AAAAI retrospective survey of FRs occurring from 1990 to 2001.9 No new FRs were directly or indirectly reported during the first year of this surveillance program (July 2008–2009), which represented SR reports from an estimated 49% of ACAAI and AAAAI members.9 In year 1, 8,502 SRs were reported, with 82% of practices experiencing at least 1 SR. Most were mild grade 1 SRs (74%), 23% were moderate (grade 2) SRs, and 3% were severe anaphylactic (grade 3) SRs.9

Previous retrospective and small prospective studies have provided estimates of the frequency of delayed-onset (beginning after 30 minutes) SRs in different clinic practices ranging between 27% and 50%.2,4,6,10–12 The national prevalence of delayed-onset SRs to SCIT injections and treatment of these have not been systematically evaluated across practices of board-certified allergists. In addition, the administration of epinephrine for early and delayed-onset SRs of varying severity has not been well studied.6,10 Therefore, during the second year of this surveillance project, we collected data regarding the time of onset of SRs of varying severity and the frequency of epinephrine (EPI) treatment.

METHODS

Study Population

Physician members of the ACAAI and AAAAI (3,919 potential respondents) were surveyed during year 2, using previously described methods.9 For multimember practices, a single respondent was identified to report the annual experience of his or her practice. Potential respondents were contacted by a nonphysician research coordinator and given the option of either completing surveys online at a dedicated website or completing and faxing back printed forms. Practice responses were confidential and were de-identified before data analysis. Multiple attempts were made to encourage initial nonresponders to reply, including contact by telephone, e-mail, or fax 4 to 6 weeks after the initial contact.9

Study Design

Physician respondents were asked to complete a 7-item questionnaire describing the entire experience of all SCIT prescribers in their clinical practices (eTable 1).9 Respondents were queried about FRs and SRs to SCIT and skin testing that had occurred in the previous 12 months in their clinical practice as well as in other clinical practices in their regional area. They were also asked to provide the numbers of mild, moderate, and severe nonfatal allergic SRs in their respective practices. Mild reactions (grade 1) were defined as generalized urticaria or upper respiratory symptoms (eg, itching of the palate and throat, sneezing). Moderate reactions (grade 2) were defined as asthmatic symptoms accompanied by a reduction in lung function (eg, a peak expiratory flow rate [PEFR] decrease of 20%–40%) with or without generalized urticaria, upper respiratory symptoms, or abdominal symptoms (nausea, cramping). Severe reactions (grade 3) were defined as life-threatening anaphylaxis with severe airway compromise (eg, PEFR decreases of more than 40%) or upper airway obstruction with stridor or hypotension (with or without loss of consciousness). These severity definitions were intended to provide guidance to respondents in terms of ranges of PEFR to retrospectively estimate and differentiate moderate and severe obstruction occurring during grades 2 and 3 systemic reactions, respectively. Because PEFR ranges appeared in parentheses, these were not intended nor inferred to be a requisite part of the definitions. Additional questions regarding the time of onset of SRs (in 10-minute increments) and treatment with EPI (yes/no) were included in the year 2 survey (eTable 1).9 The nonphysician research coordinator contacted participants reporting delayed-onset, severe grade 3 SRs regarding clinical manifestations, treatment, and outcomes of these events.

Data Analysis

A statistical software program (SAS; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) was used to compute descriptive statistics regarding reaction rates and the number of injection visits for year 2, using the same methods as for year 1.9 Similar methods were used to calculate means, standard deviations, and median numbers of early-onset (≤30 minutes) and delayed-onset (>30 minutes) SRs. Figures for the number of practices experiencing SRs, number of SRs, and number of SRs per practice were calculated. The number and percentage of patients receiving EPI for reactions of varying severity and time of onset were also determined. Categorical data analysis using a log-linear model (proc catmod in SAS) was used to evaluate relationships between the time of onset and severity of SRs and EPI administration.13

RESULTS

In year 2 of the survey, 630 practices participated, representing 1,453 practitioners. Respondents reported a total of 5.6 million injection visits, with a median of 5,261 injection visits per practice. Because single and multiple injections given at each visit could not be differentiated, the actual number of injections may be over 10 million, assuming that 2 injections were given per visit on average.

Fatal Reactions

No direct reports were made of deaths attributable to SCIT injections or allergen skin testing in the first 2 years of the surveillance study (July 1, 2008 to July 31, 2010). No indirectly reported deaths due to skin testing or SCIT injections occurred between 2008 and 2010 in community practices outside those of the respondents. As published previously, 6 confirmed fatalities related to SCIT were indirectly reported between 2001 and 2007.9

Nonfatal SRs

In year 2, SRs occurred in 85% of practices (447 of 528 providing data on total SRs) after SCIT injections. In the 445 practices that reported data on SR severity, 5,392 SRs occurred. These included 3,720 mild SRs (grade 1), translating to an annual mean of 7.6 mild SRs per clinical practice. Physician respondents reported 1,476 moderately severe (grade 2) SRs, representing 27% of all SRs and corresponding to an annual mean of 3.0 grade 2 SRs per clinical practice. Severe, potentially life-threatening (grade 3) anaphylactic reactions accounted for 3.6% of all SRs (196 events, for an annual mean of 0.4 severe SRs per practice). As indicated in Table 1, these reaction rates were similar to those reported in year 1 of the survey.9 Similar to year 1, among practices providing data on SRs, 79% (415/528) reported at least 1 grade 1 SR, 56% (295/528 ) reported at least 1 grade 2, and 17% (91/528) of respondents reported at least 1 grade 3 SR.9 Among practices who provided reaction severity grades and the number of injection visits, there were 9.7 total SRs, including 6.7 grade 1 SRs, 2.7 grade 2 SRs, and 0.4 grade 3 SRs per 10,000 injection visits. As shown in Table 2, these data were also similar to year 1 survey results.9

Table 1.

Number and Type of Systemic Reactions (SRs) between July 2008–2010

| Year 1 (7/1/2008–7/31/2009) | Year 2 (8/1/2009–7/31/2010) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of practicesa | 806 | 630 |

| Total number of SRs | 8,502 | 5,392 |

| Total SRs per practiceb | 10.5 ± 26.0 (4.0) | 10.9 ± 23.3 (5.0) |

| Grade 1 (Mild) SRs No. practices experiencing SRs |

613 | 416 |

| No. SRs | 6,293 | 3,720 |

| SRs per practiceb | 7.8 ± 20.5 (3.0) | 7.6 ± 15.5 (3.0) |

| Grade 2 (Moderate) SRs No. practices experiencing SRs |

436 | 296 |

| No. SRs | 1,944 | 1,476 |

| SRs per practiceb | 2.4 ± 6.7 (1.0) | 3.0 ± 8.3 (1.0) |

| Grade 3 (Severe) SRs No. practices experiencing SRs |

144 | 91 |

| No. SRs | 265 | 196 |

| SRs per practiceb | 0.3 ± 1.0 (0) | 0.4 ± 1.2 (0) |

The total number of practices providing complete data regarding SR severity was 804 in Year 1 and 445 in Year 2.

Mean ± standard deviation; values in parentheses represent the median number of SRs per practice.

Table 2.

Systemic Reactions (SRs) per 10,000 Injection Visitsa between July 2008 and 2010

| Year 1 (7/1/2008–7/31/2009) | Year 2 (8/1/2009–7/31/2010) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any type of SR | 10.2 | 9.7 |

| Grade 1 (mild SRs) | 7.6 | 6.7 |

| Grade 2 (moderate SRs) | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| Grade 3 (severe SRs) | 0.3 | 0.4 |

N = 626 practices in year 1 and 402 practices in year 2 providing complete data on the number of injection visits and severity of SRs.

Delayed-Onset SRs to SCIT

Given interest in the time of onset of SCIT reactions, identification of an optimal postinjection observation period, and the prevalence and severity of delayed-onset SRs (ie, beginning more than 30 minutes after an injection), questions regarding delayed-onset SRs were added to the year 2 survey (see Methods). Results can be found in Table 3. In the 267 practices responding to this portion of the survey, 226 delayed-onset SRs occurred in 78 practices; 54 were grade 2 SRs, and 9 were grade 3 SRs. The 267 practices providing complete data reported, on average, 1.0 grade 1 delayed-onset SRs, 0.3 grade 2 delayed-onset SRs, and 0.05 grade 3 delayed-onset SRs over the course of 1 year. Overall, 14% of all SRs began more than 30 minutes after SCIT injections. Notably, 10% of grade 2 SRs and 12.5% of grade 3 SRs began after more than 30 minutes.

Table 3.

Timing of Systemic Reactions (SRs) in Year 2 (August 1, 2009 to July 31, 2010)

| ≤30 minutes | >30 minutes | |

|---|---|---|

| Any type of SR (%)a Grade 1 (mild) SRs |

1,816 (86%) | 289 (14%) |

| No. practices experiencing SRs |

189 | 78 |

| No. SRs (%) | 1,293 (85%) | 226 (15%) |

| SRs per practiceb Grade 2 (Moderate) SRs |

5.9 ± 9.8 (3.0) | 1.0 ± 2.2 (0) |

| No. practices experiencing SRs |

127 | 29 |

| No. SRs (%) | 484 (90%) | 54 (10%) |

| SRs per practiceb Grade 3 (Severe) SRs |

2.4 ± 4.9 (1.0) | 0.3 ± 1.0 (0) |

| No. practices experiencing SRs |

39 | 7 |

| No. SRs (%) | 63 (87.5%) | 9 (12.5%) |

| SRs per practiceb | 0.4 ± 0.8 (0) | 0.05 ± 0.3 (0) |

Data regarding time of onset and SR severity were available for 267 practices.

Mean ± standard deviation; values in parentheses represent the median number of per practice.

Questions regarding the administration of EPI for reactions of varying severity and timing of onset were also included in the year 2 survey. These results are summarized in Figure 1. EPI was administered for 71% of early-onset grade 1 SRs. In contrast, only 56% of patients experiencing grade 1 delayed-onset SRs received EPI. A much higher percentage of patients experiencing grade 2 early-onset SRs (93%) received EPI compared with grade 2 delayed-onset reactors (67%). Early-onset grade 2 reactors were also more likely to receive EPI than early or delayed-onset grade 1 reactors. Administration for grade 3 anaphylactic reactions was high regardless of the timing of the reaction; EPI was given for 94% of early-onset grade 3 SRs and 100% of delayed-onset grade 3 SRs. Categorical data analysis (see Methods) revealed that EPI was administered significantly more often for SRs of increasing severity (P = 0.0008). A trend toward increased frequency of EPI administration for early versus delayed-onset SRs was seen (P = .07).

Figure 1.

Administration of epinephrine (EPI) in early versus delayed-onset systemic reactions (SRs). Early-onset SRs are those occurring at ≤30 minutes after injection; Delayed-onset SRs are those occurring at > 30 minutes. Gr1 = grade 1; Gr 2 = grade 2; Gr3 = grade 3. Data regarding timing, SR severity, and EPI use were available for 219 practices. For early-onset SRs, EPI was given for 912/1,293 grade 1 SRs, 450/484 grade 2 SRs, and 59/63 grade 3 SRs. For delayed-onset SRs, EPI was given for 126/226 grade 1 SRs, 36/54 grade 2 SRs, and 9/9 grade 3 SRs. *P = .0008 for the difference in EPI use based on SR severity. **P = .07 for the difference in EPI use based on the time of onset of the reaction.

Clinical details of grade 3 delayed-onset SRs obtained from 5 of 7 practices providing detailed information are listed in Table 4. The 7 practices with grade 3 delayed-onset SRs reported fewer SRs overall (mean, 6.7 ± 5.3 [median = 5.0]) than practices not experiencing these reactions. These 7 practices reported more than twice the number of early-onset grade 3 SRs (mean, 0.9 ± 1.2 [median = 0]) when compared with practices that did not report grade 3 delayed-onset SRs, however. They also reported 3 times the average number of injection visits when compared with practices not reporting grade 3 delayed-onset SRs (mean injection visits for practices experiencing grade 3 delayed-onset SRs = 16,308 ± 16,673 [median = 10,210]). In 8 of 9 patients experiencing grade 3 delayed-onset SRs, reactions began within 60 minutes of receiving an injection. Among the 5 patients for whom complete details were available (Table 4), none had experienced previous SRs. At least 2 patients experienced hypotension related to these events. All patients ultimately received EPI, with 2 patients self-administering EPI before seeking medical care. Two patients did not self-administer EPI despite previous instruction on use. Although 4 out of 5 grade 3 delayed-onset SRs began after patients left the SCIT provider’s office, 3 patients returned to receive EPI in their SCIT provider’s office. Three patients eventually received emergency room treatment, with 1 patient receiving EPI in the emergency room. None required overnight hospital admission. Various other treatments including antihistamines and systemic steroids were given. Two patients discontinued immunotherapy after the event, and 3 continued after dose adjustments were made.

Table 4.

Treatment and Outcome of Grade 3 Systemic Reactions (SRs) Occurring after 30 Minutes

| Patient | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous SRs? | None | None | None | None | None |

| Location of EPI administration? | Self-administered; multiple subsequent doses in allergist’s office | Returned to allergist’s office | ER | Returned to allergist’s office | Self-administered at girlfriend’s house |

| SR involved Hypotension? | Unknown | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown |

| ER visit? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Previously trained on self-administration of epinephrine? | Yes | Yes, (but did not self-administer) | Yes, (but did not self-administer) | No | Yes |

Abbreviations: EPI, epinephrine; ER, emergency Room.

DISCUSSION

The appropriate use of SCIT is sometimes limited by the risk of injection-related allergic SRs and rare anaphylactic FRs.7–9 Evidence-based clinical guidelines designed to minimize the risk of injection-related adverse outcomes were published in North America in 2003 and updated in 2007 and 2011.14–16 In 2008, the ACAAI and AAAAI collaborated in establishing a national surveillance database for adverse reactions to SCIT and allergen skin testing.9 Although 6 fatalities from SCIT were documented between 2001 and 2007, no FRs have been directly or indirectly reported during the first 2 years of the surveillance project (2008–2010). A longer period of surveillance (ie, 3–5 years) will be required to confirm that annual FRs are indeed declining in comparison with previous estimates.1,5,7,8

Unlike previous fatality surveys, the ACAAI and AAAAI surveillance study is unique in capturing annual incidence data of SRs of lesser severity. The recently developed World Allergy Organization classification system for anaphylaxis severity will also be incorporated in the future.17 The incidence data in this study are likely to be more reflective of the collective experience of practicing allergists across the country compared with data from previous retrospective surveys, which suffered from greater selection and recall bias.8 The percentage of practices reporting any SRs was 82% in the first year and 85% in the second year of surveillance. Reaction rates in all severity categories were also very similar for the first 2 years of the study, indicating that data gathered are likely an accurate reflection of reaction rates, despite a decline in participation in year 2.

The incidence of SRs beginning more than 30 minutes after injection was 14% in this report. This figure is much lower than that found in studies reporting retrospective data from single practices.10 Although further monitoring may be warranted, findings from this prospective national surveillance study may be more accurate than previous reports, for reasons cited.2,4,6,10–12 In addition, although severe late-onset SRs appear to be relatively rare events, they do occur, and each practice should have a plan in place to manage such events.16

Although 33% of patients experiencing delayed-onset grade 2 SRs did not receive EPI, it is encouraging that all those who experienced grade 3 anaphylaxis after leaving their SCIT prescriber’s office eventually received EPI and recovered with minimal sequelae. Notably, among patients experiencing severe delayed-onset SRs for whom complete reaction details were available, none had ever had an SR in the past. Although most of these patients had been prescribed self-injectable EPI, only half self-administered the drug before seeking medical care. This finding highlights the need for practicing allergists to consider patient education and action plans for managing rare delayed-onset SRs among SCIT patients.16 Patients should be educated on the possible signs and symptoms of a systemic reaction, counseled on appropriate treatment, and instructed to contact their SCIT provider or seek emergency medical attention should a delayed-onset SR occur.16 We recently reported that practices experiencing grade 3 SRs were more likely to prescribe self-injectable EPI than those only experiencing grade 1 SRs.18 This may reflect an effort by practices to minimize risks based on prior experience with severe SRs. In the 3rd update of the Allergen Immunotherapy Practice Parameter, an expert panel stated that “the decision to prescribe epinephrine auto-injectors to patients receiving immunotherapy should be at the physician’s discretion.”16 We believe that further studies examining the risk–benefit ratio and cost-effectiveness of prescribing self-injectable EPI to patients on SCIT are warranted.

Respondents only administered EPI in 71% of grade 1 SRs occurring within the traditional waiting period of 30 minutes. Although the specific reasons for withholding EPI are uncertain, no fatalities apparently occurred as a result of this practice. Controversy exists over the use of EPI for treating mild SRs absent manifestations consistent with the currently accepted definition of anaphylaxis (involvement of at least 2 organ systems or hypotension).7,16,19–23 Very few reports have been made of serious adverse outcomes when EPI is dosed appropriately in patients without contraindications to receiving the drug.16,21,22,24 Undue concern likely has arisen over adverse outcomes, including death from EPI toxicity, with inappropriate administration to patients misdiagnosed with anaphylaxis.22,24 For this reason, and the belief that mild cutaneous symptoms rarely progress to anaphylaxis, a European panel of experts recently recommended withholding EPI for cutaneous symptoms alone until a given reaction satisfies the generally accepted definition of anaphylaxis.20 Further study may be warranted to clarify this issue.

In summary, adverse reactions to SCIT have remained stable for the last 2 years, with no reported fatalities. Although severe SCIT reactions beginning more than 30 minutes after injection do occur, the incidence of delayed-onset reactions of all severity levels may be lower than previously reported. For grade 1 SRs, EPI was not administered in approximately one third of early-onset grade 1 SRs, and almost half of delayed-onset grade 1 SRs. Almost one third of patients experiencing delayed-onset, moderate grade 2 SRs also did not receive EPI. Further study is warranted regarding the risk–benefit ratio and cost-effectiveness of EPI administration for grade 1 SRs, as well as determining which patients receiving SCIT should receive instructions on self-administration of emergency EPI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Grant funding provided by ACAAI and AAAAI.

Footnotes

Disclosures: David I. Bernstein, MD-Clinical investigator Merck, Schering Plough, Greer, ALK, Stallergenes; Consultant—Merck, ALK, Schering Plough. Tolly G. Epstein, MD, Karen Murphy-Berendts, BS, and Gary M. Liss, MD have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.05.020.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lockey RF, Benedict LM, Turkeltaub PC, Bukantz SC. Fatalities from immunotherapy (IT) and skin testing (ST). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;79:660–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matloff SM, Bailit IW, Parks P, Madden N, Greineder DK. Systemic reactions to immunotherapy. Allergy Proc. 1993;14:347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno C, Cuesta-Herranz J, Fernandez-Tavora L, Alvarez-Cuesta E. Immunotherapy safety: a prospective multi-centric monitoring study of biologically standardized therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ragusa VF, Massolo A. Non-fatal systemic reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy: a 20-year experience comparison of two 10-year periods. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;36:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid MJ, Lockey RF, Turkeltaub PC, Platts-Mills TA. Survey of fatalities from skin testing and immunotherapy 1985–1989. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winther L, Arnved J, Malling HJ, Nolte H, Mosbech H. Side-effects of allergen-specific immunotherapy: a prospective multi-centre study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein DI, Wanner M, Borish L, Liss GM. Twelve-year survey of fatal reactions to allergen injections and skin testing: 1990–2001. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin HS, Liss GM, Bernstein DI. Evaluation of near-fatal reactions to allergen immunotherapy injections. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein DI, Epstein T, Murphy-Berendts K, Liss GM. Surveillance of systemic reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy injections: year 1 outcomes of the ACAAI and AAAAI collaborative study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:530–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rank MA, Oslie CL, Krogman JL, Park MA, Li JT. Allergen immunotherapy safety: characterizing systemic reactions and identifying risk factors. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gastaminza G, Algorta J, Audicana M, Etxenagusia M, Fernandez E, Munoz D. Systemic reactions to immunotherapy: influence of composition and manufacturer. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin MS, Tanner E, Lynn J, Friday GA Jr. Nonfatal systemic allergic reactions induced by skin testing and immunotherapy. Ann Allergy. 1993;71:557–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proc Catmod, SAS for Windows, Version 9.2; Cary, NC, SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter second update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S25–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, Calabria C, Chacko T, Finegold I, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:S1–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox L, Larenas-Linnemann D, Lockey RF, Passalacqua G. Speaking the same language: The World Allergy Organization Subcutaneous Immunotherapy Systemic Reaction Grading System. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:569–74, 74 e1–74 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liss GM, Murphy-Berendts K, Epstein T, Bernstein DI. Factors associated with severe versus mild immunotherapy-related systemic reactions: a case-referent study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1298–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons FER, Ardusso LRF, Bilo MB, El-Gamal YM, Ledford DK, Ring J, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soar J, Pumphrey R, Cant A, et al. Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions: guidelines for healthcare providers. Resuscitation. 2008;77: 157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simons KJ, Simons FE. Epinephrine and its use in anaphylaxis: current issues. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1144–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, et al. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:477–80, e1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horowitz BZ, Jadallah S, Derlet RW. Fatal intracranial bleeding associated with prehospital use of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28: 725–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.