Abstract

Context

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most frequent peripheral compression-induced neuropathy observed in patients worldwide. Surgery is necessary when conservative treatments fail and severe symptoms persist. Traditional Open carpal tunnel release (OCTR) with visualization of carpal tunnel is considered the gold standard for decompression. However, Endoscopic carpal tunnel release (ECTR), a less invasive technique than OCTR is emerging as a standard of care in recent years.

Evidence Acquisition

Criteria for this systematic review were derived from Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Two review authors searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Database in May 2018 using the following MeSH terms from 1993-2016: ‘carpal tunnel syndrome,’ ‘median nerve neuropathy,’ ‘endoscopic carpal tunnel release,’ ‘endoscopic surgery,’ ‘open carpal tunnel release,’ ‘open surgery,’ and ‘carpal tunnel surgery.’ Additional sources, including Google Scholar, were added. Also, based on bibliographies and consultation with experts, appropriate publications were identified. The primary outcome measure was pain relief.

Results

For this analysis, 27 studies met inclusion criteria. Results indicate that ECTR produced superior post-operative pain outcomes during short-term follow-up. Of the studies meeting inclusion criteria for this analysis, 17 studies evaluated pain as a primary or secondary outcome, and 15 studies evaluated pain, pillar tenderness, or incision tenderness at short-term follow-up. Most studies employed a VAS for assessment, and the majority reported superior short-term pain outcomes following ECTR at intervals ranging from one hour up to 12 weeks. Several additional studies reported equivalent pain outcomes at short-term follow-up as early as one week. No study reported inferior short-term pain outcomes following ECTR.

Conclusions

ECTR and OCTR produce satisfactory results in pain relief, symptom resolution, patient satisfaction, time to return to work, and adverse events. There is a growing body of evidence favoring the endoscopic technique for pain relief, functional outcomes, and satisfaction, at least in the early post-operative period, even if this difference disappears over time. Several studies have demonstrated a quicker return to work and activities of daily living with the endoscopic technique.

Keywords: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, Chronic Pain, Open Carpal Tunnel Release, Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release, Endoscopic Surgery, Entrapment Neuropathy, Median Neuropathy, Disability

1. Context

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is caused when the median nerve is compressed within the carpal tunnel resulting in numbness, paresthesia, and pain within the median nerve distribution of the hand. A proportion of patients may also experience progressive atrophy and loss of function of associated structures if CTS remains untreated (1). The incidence of CTS is higher in the U.S. compared to Sweden and the United Kingdom (U.K.). CTS is an important cause of work disability with profound and well-described implications for psychological and financial hardship among affected patients (2). CTS is frequently multifactorial or idiopathic, but may also be associated with trauma, diabetes, pregnancy, acromegaly, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, vibration, and certain repetitive motions of the hands and wrists.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

Criteria for this systematic review were derived from Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (3).

Two review authors searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Database in May 2018 using the following MeSH terms: ‘carpal tunnel syndrome,’ ‘median nerve neuropathy,’ ‘endoscopic carpal tunnel release,’ ‘endoscopic surgery,’ ‘open carpal tunnel release,’ ‘open surgery,’ and ‘carpal tunnel surgery.’ Additional sources, including Google Scholar, were added. In addition, based on bibliographies and consultation with experts, appropriate publications were identified.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria: The present investigation included studies that met the following criteria: randomized controlled trials (RTCs) or quasi-RCTs, inclusion of an endoscopic carpal tunnel release (ECTR) treatment arm, and reporting of pain, function, or satisfaction outcomes. Studies with follow-up time greater than one month were included in our search. Exclusion Criteria: Excluded categories were non-English papers, studies available in abstract or poster form only, and retrospective studies and case reports.

2.3. Outcomes of the Studies

The primary outcome measure was pain relief. The most commonly reported pain scores were VAS for pain, Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Symptom Severity Score (CTS-SSS), Boston Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Questionnaire Symptom severity scale (BCTQ-S), Levine Symptom Severity Score, and subjective reporting of pain. The most commonly reported secondary outcomes included Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Functional Status Score (CTS-FSS), Boston Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Questionnaire Functional status scale (BCTQ-F), pinch/grip strength, sensation (two-point discrimination, monofilament), satisfaction, operating time, and time to return to work.

2.4. Data Extraction

The final evaluation included RCTs and quasi- RCTs and observational studies. The following data were extracted and compiled into a table: author’s last name, publication year, average age, percent of sample size that was female, study size, treatment arm, endoscopic technique, follow-up time, outcomes reported, pain relief outcomes, secondary outcomes, complications, and significant conclusions. When available, mean pain scores were extracted with the intent of doing meta-analysis if possible. Please see Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies Included in our Systematic Reviewa.

| Author | Year | Average Age | Female (%) | Study Size | Groups | Endoscopic Technique | Follow-Up Times | Outcomes | Pain Relief Outcomes | Secondary Outcomes | Complications | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslani et al. ( 1 ) | 2012 | 54.2 | 90.5 | 96 pts | -Endoscopic (32 pts), -Mini-incision open (28 pts), - Open (36 pts) | Not Reported | 2, 4 weeks 4 months | Clinical symptoms, EMG, NCV, two-finger grasp strength, time to resume personal tasks, satisfaction | Night pain resolved in all three groups. Wrist pain decreased significantly in all three groups at the final follow-up. Post-operative pain at the incision site was greater for the open surgery group at weeks 2 and 4, but this difference disappeared at 4 months. | The number of positive Tinel and Phalen’s tests decreased equally for all groups at the final follow-up. Two-finger grip strength increased equally in all groups. Satisfaction was significantly greater for endoscopic release and mini-palmar incision at weeks 2 and 4, but all groups were equally satisfied at 4 months. Time to return to work and ADLs after open surgery was significantly longer by 8-15 days. | Pillar pain (n=1, endoscopic) | All three techniques produce satisfactory results with minimal complications. Endoscopic and mini-palmar incision have less pain and greater satisfaction in the first weeks, but at 4 months all groups have similar overall results. |

| Atroshi et al. ( 4 ) | 2006 | 44 | 75 | 128 pts | -Endoscopic (63 pts), - Open (65 pts | Two portal (Chow) | 3, 6 weeks , 3, 12 months | Scar and proximal palm pain and limitation of activity rating, length of work absence, CTS-SSS, CTS-FSS, SF-12 physical health score, change in hand sensation and strength, operating time | The endoscopic group had less postoperative pain and activity limitation up to 3 months, but the difference was small | The symptom severity score, change in symptom severity score over time, and SF-12 physical health scores significantly improved in both groups compared to baseline, with no difference between groups. There was no significant difference between groups in terms of length of work absence, sensory measurements, and change in strength over time. | - Partial pain relief (n=1, endoscopic), - Numbness/tingling in ulnar distribution (n=1, endoscopic) , - Recurrence of symptoms (n=1, open) | Endoscopic surgery causes modestly less pain than open surgery up to three months, but both methods are equally effective at relieving symptoms. There is no advantage regarding length of work absence |

| Atroshi et al. b | 2009 | 44 | 75 | 128 pts | -Endoscopic (63 pts), - Open (65 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | 1, 5 years | CTS-SSS, CTS-FSS, scar/palm pain, satisfaction, repeat surgery | CTS-SSS improved at 5 years compared to baseline, with no difference between groups. At 5 years, 10/63 patients treated endoscopically and 11/65 patients treated with open surgery reported persisting scar/palm pain. | CTS functional status score improved at 5 years compared to baseline, with no difference between groups. 4/65 patients reported being dissatisfied in the open group, and 4/63 patients reported dissatisfaction in the endoscopic group. | Recurrence of symptoms (n=1, endoscopic; n=2, open) | Endoscopic release is as efficacious as open release with some additional short-term benefits. The cost-benefit aspects of endoscopic release should be weighed when deciding which technique to use. |

| Atroshi et al. c | 2015 | 44 | 75 | 128 pts | -Endoscopic (63 pts), - Open (65 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | 11-16 years (average 12.8 years) | Change in CTS-SSS, change in CTS-FSS, scar and proximal palm pain, DASH scale, satisfaction, repeat surgery | CTS-SSS improved from baseline, with no difference between groups. At 11-16 years, 6/63 patients treated endoscopically and 5/65 patients treated with open surgery reported persisting scar/palm pain. | CTS functional status score improved at 11-16 years compared to baseline, with no difference between groups. There was no difference between groups for DASH scale scores, satisfaction scores, and subsequent surgery on the study hand. Overall, 4/63 treated endoscopically and 3/65 treated with open surgery required repeat surgery on the study hand. | Reoperation (n=4, endoscopic; n=3, open) | There were no significant differences between open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release at an average of 12.8 years follow-up. Functional improvement and satisfaction were durable results. |

| Brown et al. ( 5 ) | 1993 | 55 | 68.3 | 145 pts, 169 hands | -Endoscopic (76 pts, 84 hands), - Open (75 pts, 85 hands) | Two portal (Chow) | 3, 6, 12 weeks | Impairment of ADLs, return to work, two-point discrimination, grip strength, pinch strength, tenderness of palm, relief of numbness and paresthesia, satisfaction | Pain and paresthesia rating decreased in both groups, with no significant difference between groups. The endoscopic group had significantly less moderate/severe scar tenderness at 12 weeks. There was no difference in pillar tenderness between groups. | The overall satisfaction was similar between groups at 12 weeks. Two-point discrimination improved significantly in both groups, with no difference between groups. There was no significant difference in thenar weakness or atrophy, grip strength, or impairment of ADLs between groups. The endoscopic group had significantly better key-pinch values at all time points. The endoscopic group had significantly faster return to work. | Injury to superficial palmar arch (n=1, endoscopic), - Numbness postoperatively (n=1, endoscopic) , - Numbness/tingling in ulnar distribution (n=1, endoscopic), - Hematoma (n=1, endoscopic), - Transection of common digital nerve of ring/small finger and 20% of median nerve (n=1, open) | Functional outcomes are achieved more quickly when the endoscopic method is used, however with a greater rate of complications. |

| Macdermid et al. ( 6 ) | 2003 | 47.1 | 68 | 123 pts | -Endoscopic (91 pts), - Open (32 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | 1, 6, 12 weeks, 2 years | Symptom Severity Scale, McGill pain questionnaire, rate of complications, grip strength, pinch strength, sensory threshold, pain, return to work | Symptom Severity Scale improved equally well over time between groups. Open surgery resulted in significantly more pain at 1 and 6 weeks, but this difference did not persist at 12 weeks. | There was no difference between groups for rate of complications. Open surgery resulted in weaker grip at 1 and 6 weeks, but the difference did not persist at 12 weeks. Sensory threshold, pinch strength, and physical health quality of life improved in both groups, | None | There was no substantial difference in benefit between open and endoscopic release |

| Ejiri et al. ( 7 ) | 2012 | 59 | 89.9 | 79 pts, 101 hands | -Endoscopic (40 pts, 51 hands), - Open (39 pts, 50 hands) | One portal (Okutsu) | 4, 12 weeks | Changes in subjective symptoms, level of impairment in ADL, APB-DL, sensation (monofilament test and two-point discrimination test), muscle strength (grip, tip pinch, side pinch) | Both open and endoscopic groups resulted in subjective symptom improvement over time, with no difference between groups. | There were no differences in the degree of improvement in ADL impairment, APB-DL measurements, and sensation tests between groups. The degree of improvement in grip strength and tip pinch strength in the early postoperative period was greater for the endoscopic group compared to the open group. | Exacerbation of symptoms (n=2, endoscopic) | Endoscopic surgery offers superior recovery of strength in the early postoperative period, but it may carry the risk of transient nerve dysfunction. |

| Kang et al. ( 8 ) | 2013 | 55 | 92.3 | 52 pts, 104 hands | -Endoscopic (52 pts, 52 hands), -Mini-incision open (52 pts, 52 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 3 months | BCTQ-S, BCTQ-F, DASH, patient preferred technique | BCTQ and DASH scores significantly improved postoperatively in both groups, with no difference between groups. | 34 patients preferred endoscopic surgery, 13 preferred the mini-incision open surgery, and 5 had no preference. | No serious complications | Endoscopic and open surgery produced similar outcomes at 12 weeks postoperatively. The majority of patients preferred the endoscopic technique. |

| Oh et al. ( 9 ) | 2017 | 52.4 | 85.1 | 67 pts | -Endoscopic (35 pts), -Mini-incision open (32 pts) | One portal (Agee) | 24 weeks | BCTQ-S, BCTQ-F, DASH, CSA-I, CSA-M, CSA-O, FR-M, FR-O | BCTQ and DASH scores significantly improved postoperatively in both groups, with no difference between groups. | The mean CSA-I decreased, and the mean CSA-M and CSA-O increased in both groups, with no difference between groups. The mean FR-M/FR-O decreased in both groups, with no difference between groups. | No serious complications | Both endoscopic and mini-incision open surgery similarly reverse the pathological changes in the median nerve in CTS. These techniques result in similar subjective outcomes. |

| Trumble et al. ( 10 ) | 2002 | 56 | 64.6 | 147 pts, 192 hands | -Endoscopic (75 pts, 97 hands), -Open (72 pts, 95 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 52 weeks | CTS-SSS, CTS-FSS, satisfaction, sensation (monofilament and two-point discrimination test), APB strength, thenar atrophy, grip strength, pinch strength, dexterity, return to work, operating time | CTS-SSS improved throughout follow-up, but the endoscopic group had significantly better scores at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. CTS-FSS improved throughout follow-up for the endoscopic group, but in the open group improvement was not noted until the fourth week; the endoscopic group was significantly better at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. The endoscopic group had less tender scars until 12 weeks. | The endoscopic group had better satisfaction scores at 2 weeks; at later time points, both groups had equally good satisfaction scores. In both groups, postoperative sensation improved significantly, with no difference between groups. The endoscopic group recovered grip strength, pinch strength, and dexterity faster than the open group until 12 weeks. The endoscopic group had a significantly shorter time to return to work. | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (n=2, open), - Persistent symptoms (n=1, open) | Endoscopic surgery can be performed as quickly as open surgery without increased incidence of complications, and with quicker return to work. Endoscopic surgery improves patient outcomes in the first three months following surgery. |

| Michelotti et al. ( 11 ) | 2014 | 53 | 84 | 25 pts, 50 hands | -Endoscopic (25 pts, 25 hands), -Open (25 pts, 25 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 weeks | Pain, sensation (monofilament and two-point discrimination test), CTS-SSS, CTS-FSS, satisfaction, patient preferred technique | CTS-SSS and CTS-FSS improved postoperatively, with no difference between groups. Both groups reported very little pain at 2 weeks and were pain free by the end of the study. | In both groups, postoperative sensation and APB strength improved significantly, with no difference between groups. Grip strength decreased equally in the early postoperative period then reached near-preoperative levels by the end of the study. Satisfaction was significantly greater in the endoscopic group. | None | Open and endoscopic treatments are well-tolerated with no differences in functional outcomes, symptom severity, functional status, and complications. |

| Mackenzie et al. ( 12 ) | 2000 | N/A | 0 | 26 pts, 36 hands | -Endoscopic (15 pts, 22 hands), -Mini-incision open (11 pts, 14 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 1, 2, 4 weeks | Grip strength, pinch strength | Nighttime hand/wrist pain was improved significantly in the endoscopic group over the open group at week 4. | Grip strength was significantly better in the endoscopic group at weeks 2 and 4. Pinch strength improved over preoperative level in endoscopic group by week 2 but only reached statistical improvement in the open group by week 4. Hand weakness, tingling, and severity of nighttime numbness improved in the endoscopic group compared to the open group by week 2, but the difference disappeared by week 4. | Pillar pain (n=1, endoscopic; n=1, open) | Compared to open release, endoscopic release results in faster recovery of strength and it improves early postoperative comfort and function to a small degree. |

| Malhotra et al. ( 13 ) | 2007 | 45 | 58.3 | 60 pts, 61 hands | -Endoscopic (30 pts, 30 hands), -Mini-incision open (30 pts, 31 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 4, 24 weeks | Symptom amelioration, operation time, time to resume normal life, frequency of revision surgery | In the early postoperative period the endoscopic group did better symptomatically and functionally, and this group had less scar tenderness and scarring. | The endoscopic group returned more quickly to normal activity. There was no significant difference in regards to symptom amelioration, EMG testing, and complication. | - Hematoma (n=1, open), - Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (n=2, open) | Endoscopic release results in better short term results with no scar tenderness. Results at 6 months were comparable between groups. |

| Rab et al. ( 14 ) | 2006 | 56.2 | 40 | 10 pts, 20 hands | - Endoscopic (10 pts, 10 hands), -Open with two minimized incisions (10 pts, 10 hands) | Two portal (Chow) | 2, 4, 8, 12 weeks, 6, 12 months | VAS pain, Levine Symptom Severity Score, Levine Functional Status Scale, two-point discrimination, grip strength, pinch strength, key grip strength | Both groups had significant postoperative improvements in VAS pain scores, Levine scores, and sensory testing, with no difference between groups | Grip strength, pinch strength, and key grip strength showed no improvement or worsening, with no difference between groups. | None | There were no advantages of the endoscopic approach over the open technique. |

| Saw et al. ( 15 ) | 2003 | 52 | 73.3 | 150 pts | -Endoscopic (74 pts), -Open (76 pts) | One portal (Agee) | 1, 3, 6, 12 weeks | Levine Symptom Severity Score, Levine Functional Status Scale, VAS anterior carpal pain, grip strength, return to work, operating time | There was no significant difference between groups in regards to symptom severity scores, functional status scores, anterior carpal pain, and grip strength. | The endoscopic group returned to work significantly earlier than the open group. The operation time for the endoscopic group was significantly longer. | -Transient index finger numbness (n=1, endoscopic), - Hyperaesthesia (n=1, open) , - Hematoma (n=1, open), - Superficial wound infection (n=1, open; n=1, endoscopic) , - Persistent symptoms (n=1, open; n=1, endoscopic) | Endoscopic release should be considered in employed patients as a cost-effective procedure. This may not be true in the general population as a whole. |

| Chandra et al. ( 16 ) | 2013 | 45.6 | 82.7 | 100 pts | -Endoscopic < 1 week from diagnosis (51 pts), -Endoscopic > 6 months from diagnosis (49 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | >6 months (mean 7.2 months) | EP improvement, general improvement, nocturnal awakening, severity of most important symptom, satisfaction, use of pain medication, CTS-SSS, CTS-FSS | There was significant improvement in clinical scores postoperatively for both groups. The early group had significantly better improvement than the delayed group. | At follow-up, everyone in the early group had returned to work, which was significantly more than in the delayed group where 11% had complete return to normal activity, and 89% had partial return. There was significant postoperative improvement of EP measurements for both groups, but improvement was significantly better for the early group. | None | Early endoscopic surgery should be preferred over late surgery in patients with moderately severe CTS. |

| Gümüştaş et al. ( 17 ) | 2015 | 45.5 | 95.1 | 41 pts | -Endoscopic (21 pts), -Open (20 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | 6 months | BCTQ-S, BCTQ-F, EP improvement | The BCTQ-S and BCTQ-F scores improved significantly from baseline, with no difference between groups. | The mean EMG measurements generally improved from baseline, with no difference between groups. | - Fifth finger flexor digitorum superficialis injury (n=1, endoscopic), - Persistent symptoms (n=1, endoscopic) , - Superficial wound infection (n=1, open) | Endoscopic release is both clinically and electrophysiologically as effective as open surgery for the treatment of CTS. |

| Orak et al. ( 18 ) | 2016 | 46.8 | 86.8 | 53 pts | -Endoscopic (22 pts), -Open (28 pts) | Two portal (Chow | 1, 2, 4, 24 hours, 6 weeks | BCTQ-S, BCTQ-F, VAS pain | The BCTQ-S and BCTQ-F scores improved significantly from baseline at 6 weeks. The endoscopic group had significantly lower VAS pain scores at 1, 2, 4, and 24 hours. | The endoscopic group had significantly lower analgesic use in the first 24 hours. | - Fifth finger flexor digitorum superficialis injury (n=1, endoscopic), - Post-operative scar pain (n=3, open) | Endoscopic release is an effective treatment for CTS especially in regards to postoperative pain relief. |

| Agee et al. ( 19 ) | 1992 | N/A | N/A | 122 pts, 147 hands | -Endoscopic (82 hands), -Open (65 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 13, 26 weeks | Employment status, return to ADLs, grip strength, pinch strength, monofilament testing, motor testing of thenar muscles, scar tenderness, radial/ulnar pillar tenderness | Pain decreased postoperatively in both groups, with no difference between groups. The endoscopic group experienced less scar tenderness at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 9, as well as less radial pillar tenderness at weeks 3 and 9, and less ulnar pillar tenderness at week 1. | The endoscopic group returned to preoperative strength significantly faster than the open group. Motor levels and Tinel’s and Phalen’s test scores improved equally between groups. The median time to return to work was significantly greater in the open group. | - Persistent symptoms (n=2, endoscopic) , - Transient ulnar neuropraxia (n=2, endoscopic) , - Injury to deep motor branch of ulnar nerve (n=1, open) , - Bowstringing of digital flexor tendons (n=1, open) , - Wound dehiscence (n=2, open) | Endoscopic release offers the benefit of dividing only the transverse carpal ligament, without disrupting the overlying skin, fat, fascia, and palmaris brevis. Endoscopic release results in some improved outcomes over open surgery, and this translates to quicker return to work and ADLs. |

| Sennwald et al. ( 20 ) | 1995 | 52.6 | 78.7 | 48 pts. | -Endoscopic (25 pts), -Open (22 pts) | One portal (Agee) | 4, 8, 12 weeks | Pain, grip strength, key-pinch strength, return to work | Not reported | Recovery of grip strength was significantly better in the endoscopic group at all follow-up points. Recovery of key-pinch strength did not differ between groups. The endoscopic group had a significantly faster return to work (24 days compared to 42 days in the open group). The open group had significantly more widening of the carpal arch, but this did not correlate with grip or pinch strength. | -Transient neuropraxia (n=1, endoscopic) , - Hypertrophic scar (n=1, open) , - Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (n=1, open) | While the results of this study strongly favor endoscopic release, this technique does not allow exploration inside the carpal tunnel. |

| Dumontier et al. ( 21 ) | 1995 | 52.3 | 88.5 | 96 pts | -Endoscopic (56 pts), -Open (40 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | 2 weeks, 1, 3 months | Numbness, pain, return to work, grip strength, finger mobility | Both groups had decreased pain postoperatively, with no difference between groups over time | There was no difference between groups in regards to postoperative numbness and time to return to work. The endoscopic group had faster grip strength recovery at 1 and 3 months. Finger flexion was complete in both groups by 1 month. | -Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (n=2, endoscopic; n=2, open) | No differences were found regarding pain, numbness, or return to work. The endoscopic group was better in terms of recovery of grip strength. |

| Jacobsen et al. ( 22 ) | 1996 | 46 | 72.4 | 29 pts, 32 hands | -Endoscopic (16 hands), -Open (16 hands) | Two portal (Chow) | 2 weeks, 6 months | Two-point discrimination, EP findings, sick leave days, number of analgesics | Not reported | EP testing improved in all patients. There was no difference between groups for EP testing and number of sick leave days. There was no difference in the number of analgesics taken between groups. | -Transient numbness on radial side of ring finger (n=3, endoscopic) , - Prolonged secretion from wound (n=1, open) | There were no differences found between endoscopic and open release. Several patients in the endoscopic group had transient numbness of their ring finger. |

| Ferdinand et al. ( 23 ) | 2002 | 54.9 | 80 | 25 pts, 50 hands | -Endoscopic (25 pts, 25 hands), - Open (25 pts, 25 hands) | One portal (Agee) | 6, 12, 26, 52 weeks | Pain in scar, tenderness of palm, satisfaction, ADLs, thenar muscle strength, lateral pinch strength, grip strength, goniometry of wrist and finger movement, two-point discrimination, manual dexterity, operating time | Not reported | Endoscopic release was associated with a significantly longer operating time compared to open release. There was no difference between groups for time to return to ADLs, hand function tests, grip strength, sensation, and satisfaction. | -Persisting wound pain (n=1, endoscopic; n=1, open), - Persistent symptoms (n=1, open), - Superficial sensory nerve injury (n=1, open) | Endoscopic release has no specific advantages over open release in terms of muscle strength, hand function, grip strength, manual dexterity or sensation. Endoscopic release is a slightly longer surgery. |

| Wong et al. ( 24 ) | 2003 | 47 | 93.3 | 30 pts, 60 hands | -Endoscopic (30 pts, 30 hands), -Limited open (30 pts, 30 hands | Two portal (modified Chow) | 2, 4, 8, 16 weeks, 6, 12 months | VAS pain, pillar pain, two-point discrimination, range of movement, grip strength, pinch strength, patient preferred technique, operating time | VAS pain decreased postoperatively in both groups, with the limited open group experiencing significantly greater pain reduction at 2 and 4 weeks. Pillar pain was also decreased in the limited open group compared to the endoscopic group at 8 weeks. | The mean operating time, percent of patients with resolved symptoms, sensory recovery, and grip strength were not significantly different between groups. There was a significant patient preference for limited open release. | -Trigger finger (n=3, endoscopic; n=3 open) | Outcomes between limited open and endoscopic release were similar at one year follow-up. However, the limited open group had less scar tenderness and pillar pain in the early postoperative period. Limited open is simple and avoids the potential complications of endoscopic release. |

| Larsen et al. ( 25 ) | 2013 | 51 | 71.1 | 90 pts | -Endoscopic (30 pts), -Open (30 pts), -Short incision open (30 pts) | One portal (Menon technique) | 1, 2, 3, 6, 12, 24 weeks | VAS pain, VAS paresthesia, grip strength, range of movement, pillar pain, duration of sick leave | There was no difference in terms of postoperative pain and paresthesia between the groups. | The endoscopic group tended to heave earlier return of grip strength, range of movement, and return to work. The odds ratio for return to work within 2 weeks was 5 and 1.2 times larger for the endoscopic and short incision group compared to the classic incision group. The endoscopic and classic incision groups had significantly larger improvement in grip strength at 6 and 12 weeks, compared to the short incision group. | -Transient ulnar paresthesia (n=2, endoscopic) , - Pillar pain at furthest follow-up (n=4, endoscopic; n=4, short incision; n=7, open) | Endoscopic release is safe and allows for faster recovery and return to work. |

| Erdmann ( 26 ) | 1994 | 53.4 | 61.5 | 71 pts, 105 hands | -Endoscopic (47 pts, 78 hands), -Open (47 pts, 77 hands) | Two portal (Chow) | 1, 2 weeks, 1, 3, 6, 12 months | VAS pain, return to work, return to preoperative grip strength, return to preoperative pinch strength | The endoscopic group had significantly lower VAS up to 1 month, but the difference disappeared at later time points. | The endoscopic group had significantly faster return to work, return to preoperative grip strength, and return to preoperative pinch strength. There was no difference between groups in terms of time to relief of symptoms. | -Ulnar nerve parasthesia (n=1, endoscopic) , - Recurrence of symptoms (n=1, endoscopic) | Endoscopic release has advantages over open surgery, specifically earlier recovery of hand strength and return to work as well as decreased postoperative pain and reduction in scar tenderness. |

| Zhang et al. ( 27 ) | 2016 | 46.4 | 66.2 | 207 pts | -Endoscopic (69 pts), -Open (65 pts), -Double small incision open (73 pts) | Two portal (Chow) | 2 years | Sensation (two-point discrimination, monofilament), severity of symptoms and functional status (Levine-Katz Questionnaire), pinch strength, return to work, VAS scar pain, satisfaction | There was no difference between groups in regards to postoperative scar pain or symptom severity | Endoscopic release and double small incision were associated with a significantly shorter return to work compared to standard open release. There was no difference between groups in sensibility, functional status, or hand strength. Patients were significantly more satisfied with endoscopic release compared to the other treatments | None | Carpal tunnel surgery with a double small incision is minimally invasive, less technically challenging, and results in good nerve visualization and postoperative scar appearance. |

Abbreviations: EMG: Electromyography; NCV: Nerve Conduction Velocity; CTS: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome; DASH: Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; APB-DL: Distal motor Latency to the Abductor Pollicis Brevis; BCTQ-S: Boston Carpal Tunnel syndrome Questionnaire Symptom severity scale; BCTQ-F: Boston Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Questionnaire Functional status scale; CSA-I/M/O: Cross Sectional Area – Inlet/Middle/Outlet; FR-M/O: Flattening Ratio – Middle/Outlet; CTS-SSS: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Symptom Severity Score; CTS-FSS: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Functional Status Score; APB: Abductor Pollicis Brevis; EP: Electrophysiology; N/A = Not Available.

aNB: The following studies were solely bilateral CTS. Michelotti et al. (11), Rab et al. (14), Ferdinand et al. (23), Wong et al. (24), Kang et al. (8).

2.5. Assessment of Study Quality

Two authors (SO and VO) used the Cochrane Risk of Bias to measure the methodological quality of the RCTs. The Cochrane Risk of Bias has seven items included to assess the internal validity of each of the RCTs. Each of the studies are scored via the allocation of “+,” “-,” or “?” to each criterion that is met or unmet (29). Please see Table 2.

Table 2. Risk of Bias Analysis, Risk of Bias was Ascertained by Two Separate Reviewers Using the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Framework. Symbols Signify Low Risk of Bias (+), High Risk of Bias (-), and Uncertain Risk of Bias (?)a.

| Reference | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslani et al. ( 30 ) 2012 | ? | ? | - | - | + | ? | + |

| Atroshi et al. ( 4 ) 2006 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| Atroshi et al. ( 31 ) 2009 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| Atroshi et al. ( 28 ) 2015 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| Brown et al. ( 5 ) 1993 | - | - | - | + | ? | - | + |

| Macdermid et al. ( 6 ) 2003 | ? | ? | - | + | ? | ? | ? |

| Eljiri et al. ( 7 ) 2012 | + | ? | - | - | + | + | + |

| Kang et al. ( 8 ) 2013 | + | ? | - | + | + | ? | + |

| Oh et al. ( 9 ) 2017 | + | ? | - | + | + | ? | + |

| Trumble et al. ( 10 ) 2002 | ? | - | - | + | ? | - | + |

| Michelotti et al. ( 11 ) 2014 | + | - | - | ? | + | ? | + |

| Mackenzie et al. ( 12 ) 2000 | ? | - | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Malhotra et al. ( 13 ) 2007 | ? | ? | - | - | ? | ? | + |

| Rab et al. ( 14 ) 2006 | ? | - | - | - | + | - | ? |

| Saw et al. ( 15 ) 2003 | + | ? | - | + | + | ? | - |

| Chandra et al. ( 16 ) 2013 | + | + | - | + | + | ? | + |

| Gümüştaş et al. ( 17 ) | + | ? | - | + | + | ? | + |

| Orak et al. ( 18 ) 2016 | + | ? | - | - | ? | ? | + |

| Agee et al. ( 19 ) 1992 | ? | - | - | - | ? | ? | - |

| Sennwald et al. ( 20 ) 1995 | + | ? | - | - | + | ? | ? |

| Dumontier et al. ( 21 ) 1995 | ? | - | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Jacobsen et al. ( 22 ) 1996 | ? | ? | - | - | + | ? | ? |

| Ferdinand et al. ( 23 ) 2002 | + | ? | - | + | ? | ? | ? |

| Wong et al. ( 24 ) 2003 | + | ? | - | - | ? | - | + |

| Larsen et al. ( 25 ) 2013 | + | + | - | + | + | ? | + |

| Erdmann ( 26 ) 1994 | ? | ? | - | - | ? | ? | - |

| Zhang et al. ( 27 ) 2016 | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | + |

a1: Random Sequence Generation, 2: Allocation Concealment, 3: Blinding of Participants and Personnel, 4: Blinding of Outcome Assessment, 5: Incomplete Outcome Data, 6: Selective Reporting, 7: Other Bias.

2.6. Analysis of Evidence

For this systematic review, evidence synthesis was performed utilizing a qualitative modified approach to the grading of evidence, modified and collated from multiple available criteria, including Cochrane review criteria and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) criteria (32).

2.7. Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis was not performed in this systematic review because of the nature of active control trials showing no significant difference between the two groups, and both approaches have been shown to be effective in the past. Please see Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

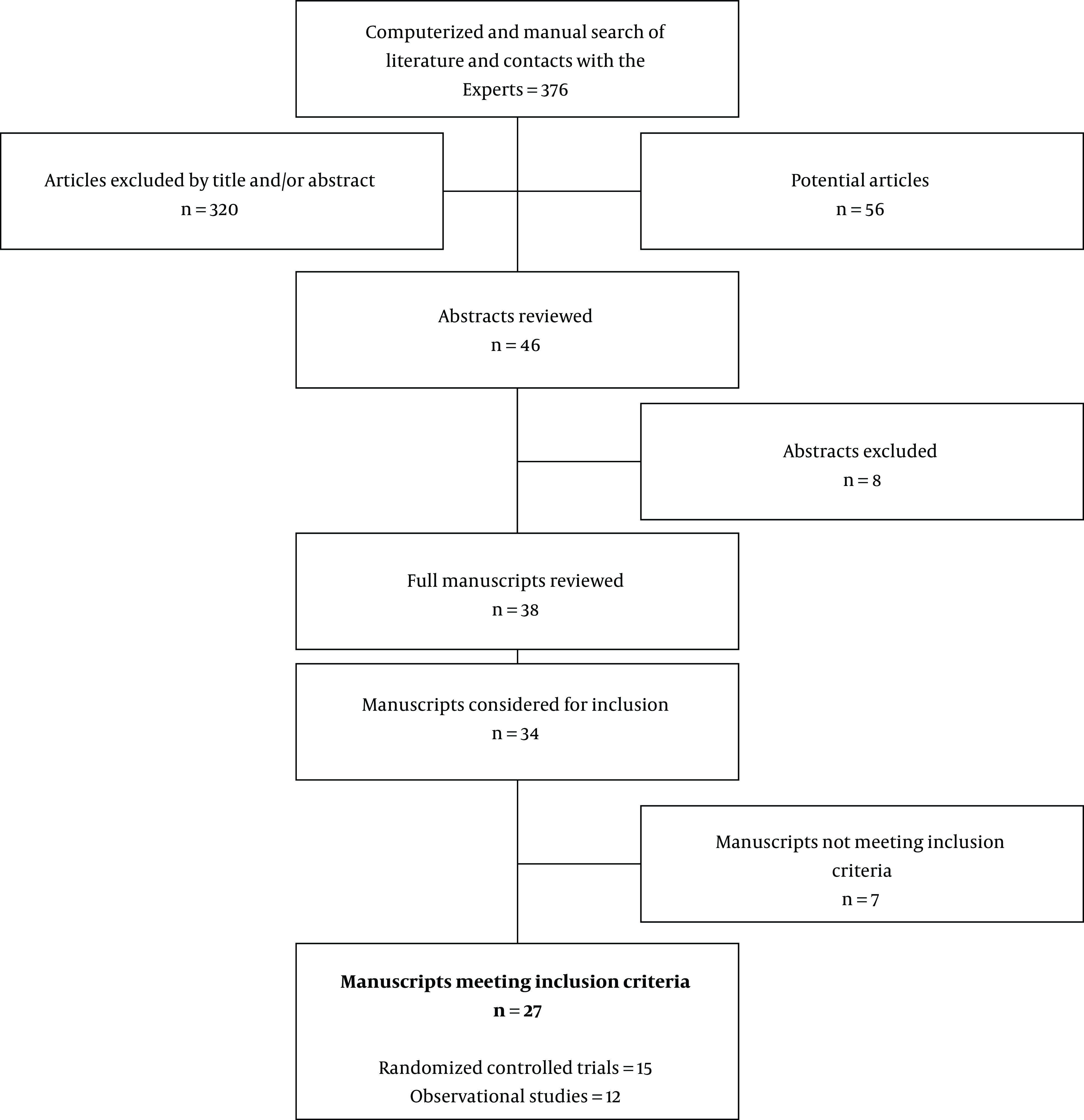

Thirty-four studies were identified for preliminary review. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 27 studies with 1,920 patients were included for systematic review (Figure 1). The mean age was 49, with 78.1% of patients being female. The techniques used for ECTR, listed in descending order, were the Chow (33), Agee (19), and Okutsu (34). The studies were published between 1992 and 2018, and the follow-up time ranged from one week to 16 years. A summary of the studies included in this review is displayed in Table 1. Our search identified 15 RCTs and 12 observational studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram illustrating published literature evaluating endoscopic vs. open surgical techniques of carpal tunnel decompression.

3.2. Pain Relief

In 24 studies, both open and endoscopic techniques resulted in significant pain relief postoperatively. Endoscopic surgery resulted in a significantly greater pain relief in 10/24 studies, usually in the early post-operative period. For example, Aslani et al. (30) showed that post-operative pain at the incision site was greater for the open surgery group at weeks 2 and 4, but the difference disappeared at four months post-surgery. MacDermid et al. (6) showed that open surgery resulted in significantly more pain at weeks 1 and 6, but this difference did not persist at 12 weeks post-surgery. Trumble et al. (10) demonstrated that CTS-SSS and CTS-FSS improved more for the endoscopic group at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 post-surgery. Other significant findings in favor of the endoscopic group were improvement of night-time hand and wrist pain at week 4 post-surgery (12), improvement of symptoms and function (13), improvement in VAS pain scores at hours 1, 2, 4, and 24 post-surgery (18), improvement of scar tenderness at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 9 post-surgery and radial pillar tenderness at weeks 3 and 9 (19), and improvement of VAS pain up to 1-month post-surgery (26).

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

Several studies showed that endoscopic release produced a greater improvement of grip and/or pinch strength in the early post-operative period (7, 12, 18, 20, 21, 25, 26). According to Orak et al. (18), there was less analgesic use in the endoscopic group in the first 24 hours postoperatively. According to two studies, satisfaction was significantly greater for the endoscopic group in the early post-operative period, but this difference disappeared at later time points (10, 30). Several other studies showed similar satisfaction between open and endoscopic groups (5). Overall, endoscopic surgery resulted in a faster return to work in most studies (5, 13, 15, 19, 20, 25-27). Two studies showed a longer operating time for endoscopic surgery versus open surgery.

3.4. Complications

Adverse events between endoscopic and open surgery were about equal (ECTR = 43, OCTR = 44). In the endoscopic group, the most commonly reported complications were post-operative numbness/tingling (n= 13), pillar pain (n = 6), and persistence or exacerbation of symptoms (n = 6). In the open group, the most commonly reported complications were pillar pain (n = 9), reflex sympathetic dystrophy (n = 7), and hypertrophic/painful scar (n = 5). There were four instances of re-operation in the endoscopic group and three instances of re-operation in the open group.

4. Conclusions

For this analysis, 27 studies met inclusion criteria. Results indicate that ECTR produced superior post-operative pain outcomes (decreased pain score) during short-term follow-up. Of the studies meeting inclusion criteria for this analysis, 17 studies evaluated pain as a primary or secondary outcome and 15 studies evaluated pain, pillar tenderness, or incision tenderness at short-term follow-up. Most studies employed a VAS for assessment and the majority reported superior short-term pain outcomes following ECTR at intervals ranging from 1 hour up to 12 weeks (6, 12, 18-20, 24, 30, 31). Several additional studies reported equivalent pain outcomes at short-term follow-up as early as one week (5, 14, 15, 21, 25). No study reported inferior short-term pain outcomes following ECTR.

Interestingly, pain scores following endoscopic and OCTR techniques were equivalent in long-term follow-up, even after superiority of post-operative pain scores in the early post-operative period. Several studies report equalization or narrowing of benefit at follow-up time points ranging from 12 weeks to one year (6, 10, 18, 19, 24, 26, 31). No study reports superior pain outcomes at long-term follow-up exceeding one year for endoscopic, open, or mini-incision carpal tunnel release techniques.

Of the included studies, 24 studies reported outcomes pertaining to grip strength, pinch strength, and functional status. Most studies reported equivalent outcomes in grip or pinch strength at post-operative time points ranging from 1 week to one year (5, 9, 14, 15, 20, 23-25, 27). Several studies also reported equivalent functional status using BCTQ-F and CTS-FFS scales at time points as early as 6 weeks (11, 17, 18).

A subset of studies reported contradicting findings related to transient superiority or inferiority of functional status following endoscopic release. Of groups reporting favorable outcomes following endoscopic release, Aslani et al. (30) reported persistent weakness following OCTR relative to mini-incision or endoscopic release, MacDermid et al. (6) reported superior grip strength following endoscopic release at 1 and 6 weeks, Sennwald et al. (20) reported superior grip strength at 3 months, but equivalent pinch strength at all time points and Trumble et al. (10) reported superior functional status using the CTS-FSS scale at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Atroshi et al. (4, 28, 31) also reported a less severe post-operative loss of strength following endoscopic release, with a return of strength following both ECTR and OCTR at 3-month follow-up. Of studies reporting favorable outcomes following OCTR, Ejiri et al. (7) reported exacerbation of functional impairment in two hands, and Kang et al. (8) reported that transient worsening of symptoms was a commonly reported complaint among surveyed patients at three months follow-up after ECTR. Despite these potential transient discrepancies in strength and functional status, each study reported dissipation of any difference by three months (6, 20, 31).

Predictably, this early trend in pain and functional outcomes following ECTR was mirrored in patient-reported satisfaction scores. Studies either reported equivalent patient satisfaction (5, 27, 28, 31) or higher patient satisfaction following endoscopic release as late as 6 months postoperatively (4, 10, 11, 30). Superior short-term pain and functional status outcomes following endoscopic release did translate to improved short-term patient satisfaction scores in select studies. However, like pain and functional status assessments, patient satisfaction became equivalent at intermediate and long-term follow-up.

Based on 27 RCTs published from 1993-2016, ECTR and OCTR produce satisfactory results in pain relief, symptom resolution, patient satisfaction, time to return to work, and adverse events. There is a growing body of evidence favoring the endoscopic technique in pain relief, functional outcomes, and satisfaction, at least in the early postoperative period, even if this difference disappears over time. Several studies have demonstrated a quicker return to work and activities of daily living with the endoscopic technique.

Footnotes

Authors' Contribution: Study concept and design: VO SO JP IU MSO MJ analysis and interpretation of data: LM ADK CO SH drafting of the manuscript: EMC FI GV OV critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: VO SO JP IU MSO MJ LM statistical analysis: ADK CO SH EMC FI GV OV.

Conflict of Interests: Alan Kaye is on the Speakers Bureau for Merck Pharmaceuticals.

Funding/Support: There is no funding/support.

Contributor Information

Vwaire Orhurhu, Email: vwo569@mail.harvard.edu.

Sebastian Orman, Email: so242@georgetown.edu.

Jacquelin Peck, Email: jeepeck@gmail.com.

Ivan Urits, Email: ivanurits@gmail.com.

Mariam Salisu Orhurhu, Email: salisumb@gmail.com.

Mark R. Jones, Email: jarkmones@gmail.com.

Laxmaiah Manchikanti, Email: drlm@thepainmd.com.

Alan D. Kaye, Email: akaye@lsuhsc.edu.

Charles Odonkor, Email: kcodonkor@aya.yale.edu.

Sameer Hirji, Email: shirji@partners.org.

Elyse M. Cornett, Email: ecorne@lsuhsc.edu.

Farnad Imani, Email: farnadimani@yahoo.com.

Giustino Varrassi, Email: giuvarr@gmail.com.

Omar Viswanath, Email: viswanoy@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Atroshi I, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Tagil M, Petersson IF. Incidence of physician-diagnosed carpal tunnel syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):943–4. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Sprinchorn A. Symptoms, disability, and quality of life in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(2):398–404. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(99)70014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 2015 doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.552-554. Available from: http://prisma-statement.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Atroshi I, Larsson GU, Ornstein E, Hofer M, Johnsson R, Ranstam J. Outcomes of endoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome among employed patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7556):1473. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38863.632789.1F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown RA, Gelberman RH, Seiler JG, Abrahamsson SO, Weiland AJ, Urbaniak JR, et al. Carpal tunnel release. A prospective, randomized assessment of open and endoscopic methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(9):1265–75. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macdermid JC, Richards RS, Roth JH, Ross DC, King GJ. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a randomized trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(3):475–80. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ejiri S, Kikuchi S, Maruya M, Sekiguchi Y, Kawakami R, Konno S. Short-term results of endoscopic (Okutsu method) versus palmar incision open carpal tunnel release: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2012;58(1):49–59. doi: 10.5387/fms.58.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang HJ, Koh IH, Lee TJ, Choi YR. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release is preferred over mini-open despite similar outcome: a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1548–54. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh WT, Kang HJ, Koh IH, Jang JY, Choi YR. Morphologic change of nerve and symptom relief are similar after mini-incision and endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a randomized trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, Gilbert-Anderson MM. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release : a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1107–15. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michelotti B, Romanowsky D, Hauck RM. Prospective, randomized evaluation of endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome: an interim analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73 Suppl 2:S157–60. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackenzie DJ, Hainer R, Wheatley MJ. Early recovery after endoscopic vs. short-incision open carpal tunnel release. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44(6):601–4. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200044060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra R, Kiran EK, Dua A, Mallinath SG, Bhan S. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: A short-term comparative study. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(1):57–61. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.30527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rab M, Grunbeck M, Beck H, Haslik W, Schrogendorfer KF, Schiefer HP, et al. Intra-individual comparison between open and 2-portal endoscopic release in clinically matched bilateral carpal syndrome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(7):730–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saw NLB, Jones S, Shepstone L, Meyer M, Chapman PG, Logan AM. Early Outcome and Cost-Effectiveness of Endoscopic Versus Open Carpal Tunnel Release: A Randomized Prospective Trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;28(5):444–9. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(03)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra PS, Singh PK, Goyal V, Chauhan AK, Thakkur N, Tripathi M. Early versus delayed endoscopic surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome: prospective randomized study. World Neurosurg. 2013;79(5-6):767–72. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gumustas SA, Ekmekci B, Tosun HB, Orak MM, Bekler HI. Similar effectiveness of the open versus endoscopic technique for carpal tunnel syndrome: a prospective randomized trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(8):1253–60. doi: 10.1007/s00590-015-1696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orak MM, Gumustas SA, Onay T, Uludag S, Bulut G, Boru UT. Comparison of postoperative pain after open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release: A randomized controlled study. Indian J Orthop. 2016;50(1):65–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.173509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agee JM, McCarroll H, Tortosa RD, Berry DA, Szabo RM, Peimer CA. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: A randomized prospective multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):987–95. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sennwald GR, Benedetti R. The value of one-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a prospective randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3(2):113–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01552386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dumontier C, Sokolow C, Leclercq C, Chauvin P. Early Results of Conventional Versus Two-Portal Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release. J Hand Surg Br. 2016;20(5):658–62. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(05)80130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobsen MB, Rahme H. A Prospective, Randomized Study with an Independent Observer Comparing Open Carpal Tunnel Release with Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release. J Hand Surg Br. 2016;21(2):202–4. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(96)80097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferdinand RD, MacLean JGB. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84-B(3):375–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b3.0840375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong KC, Hung LK, Ho PC, Wong JMW. Carpal tunnel release. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-B(6):863–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b6.13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen MB, Sorensen AI, Crone KL, Weis T, Boeckstyns ME. Carpal tunnel release: a randomized comparison of three surgical methods. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(6):646–50. doi: 10.1177/1753193412475247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erdmann MWH. Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Decompression. J Hand Surg Br. 2016;19(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Huang X, Wang X, Wen S, Sun J, Shao X. A Randomized Comparison of Double Small, Standard, and Endoscopic Approaches for Carpal Tunnel Release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(3):641–7. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atroshi I, Hofer M, Larsson GU, Ranstam J. Extended Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial of Open vs Endoscopic Release Surgery for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1399–401. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, Maher CG, Deyo RA, Schoene M, et al. 2015 Updated Method Guideline for Systematic Reviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(21):1660–73. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aslani HR, Alizadeh K, Eajazi A, Karimi A, Karimi MH, Zaferani Z, et al. Comparison of carpal tunnel release with three different techniques. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(7):965–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atroshi I, Hofer M, Larsson GU, Ornstein E, Johnsson R, Ranstam J. Open compared with 2-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a 5-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(2):266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manchikanti L, Falco FJ, Benyamin RM, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, Hirsch JA. A modified approach to grading of evidence. Pain Physician. 2014;17(3):E319–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow JC, Hantes ME. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release: thirteen years' experience with the Chow technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(6):1011–8. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.35884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okutsu I. How I developed the world's first evidence-based endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand Surg. 2010;15(3):149–55. doi: 10.1142/S0218810410004850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]