Abstract

Background:

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-30) is a popular instrument that has been ratified and is being used around the world as a screening tool for over three decades. However, a validated version of the scale is not available for use among speakers of Malayalam. In this paper, we elaborate on the procedure involved in the translation and validation of the GDS-30 from the official English version into Malayalam, the hurdles encountered in the process, and how they were overcome.

Methods:

The steps recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) were applied for the translation of the original questionnaire. This involved initial forward translation of the English questionnaire, discussion by an expert panel, back-translation, pre-testing, and pilot testing of the final version. The Malayalam translation thus obtained was administered to 100 elderly persons in the community. These individuals were then examined by a qualified doctor, who had received the necessary training from a consultant psychiatrist in the diagnosis of depressive disorders. This doctor evaluated the study subjects clinically using theInternational Classification of Diseases-tenth revision (ICD-10) criteria for the diagnosis of depression, which is considered as the gold standard. Sensitivity, specificity, Cronbach'salpha, and split-half reliability were calculated to determine validity.

Results:

The translated scale yielded a sensitivity of 87.20%, a specificity of 73.80%, an area under the Receiving Operator Curve (ROC) of 0.814, Cronbach's α of 0.920, and split-half reliability of 0.897, thereby proving to be a valid screening tool.

Conclusion:

The Malayalam translation of the GDS-30 is a valid instrument to screen for depression in an elderly Malayalam-speaking population.

Keywords: Depression, GDS-30, geriatric depression scale, Malayalam

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of morbidity and diminished quality of life worldwide.[1] Studies have shown that 34.4% of Indians above 65 years of age have depressive symptoms, yet the diagnosis is often missed, and the early signs of depression are frequently overlooked.[2] The National Mental Health Survey of India revealed that the treatment gap for MDD in India is over 85%, i.e., only 15 out of 100 persons suffering from depression seek treatment.[3] To add to the problem, there is an acute shortage of psychiatrists in India, with only an estimated 9000 qualified psychiatrists, and an additional 27000 required to ensure the provision of mental health services throughout the breadth of the country.[4] In such a scenario, primary care physicians have an important role to play in closing the treatment gap for MDD. With the right training, patients with mild and moderate depression can be identified and effectively managed by physicians in primary care settings.[5]

Quantitative scales and questionnaires are utilized both in clinical practice and in the public health domain to identify cases early and to evaluate the response to treatment. They may be especially useful to screen for psychiatric disorders in primary care settings and in the community at large. However, questionnaires may neither be adapted to the local population nor available in regional languages. Hence, investigators may need to generate a new questionnaire or translate an existing one into the native tongue of the study population.[6]

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-30) is a popular screening tool for depression that has been effectively employed in both clinical and research settings for over three decades. Although the scale has been translated into Hindi and a few regional languages like Kannada, Tamil, Gujarati, and Bengali, its translation into Malayalam, the native tongue in the south Indian state of Kerala, and subsequent validation, has not yet been undertaken.[7,8,9,10] Moreover, there is a dearth of research on the subject of geriatric depression in India, and studies conducted using the Malayalam translation of the GDS-30 questionnaire may help to fill this void. Hence, this study was undertaken to translate the GDS-30 questionnaire from the original English version into Malayalam and to validate the questionnaire for its use among an elderly population speaking Malayalam.

Materials and Methods

About the GDS-30 questionnaire

The GDS-30 was developed in 1982 by Jerome Yesavage, Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology at Stanford University.[11] It was compared with both the benchmark scales for depressive symptomology that were in use at the time, namely the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRS-D) and the Zung Self Rating Depression Scale (SDS). The tool returned a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 89% when evaluated against diagnostic criteria.[12] For the last three decades, it has been used extensively in both clinical and research settings.

The GDS-30 is a self-rated questionnaire that assesses the participant's mood in the week preceding the time of administration. Participants are expected to respond with either 'yes' or 'no' to questions concerning their prevailing mood. It is a 30-item questionnaire with each item given a score of one point, hence bringing the total score to 30. On completion, all the affirmative items are added up to obtain the final tally.

A score of 0-9 is considered “normal”, 10-19 as “mildly depressed”, and 20-30 as “severely depressed”. The GDS-30 is used both as a screening tool and as a measure of clinical improvement or deterioration by comparing scores across a fixed time period.

Methodology of translation

Two groups were constituted for the purpose of the study. The bilingual group, fluent in both English and Malayalam, was tasked with discussing various aspects of the translation process, foreseeing possible roadblocks, and resolving procedural issues related to translation. The second group, which was monolingual, read the translated document, and provided constructive criticism and commentary on the final draft. The translated tool was evaluated for grammar, syntax, and context.

The following steps recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) were used for translating the English version of the GDS-30 Questionnaire into Malayalam.[13]

-

Initial Forward Translation

This was carried out by a bilingual health professional with expertise in public health and a good scientific understanding of the subject of the study. The translator aimed at the conceptual and semantic equivalence of a word or phrase, and not a word-for-word translation. Every attempt was made to translate into simple, clear, concise, and non-offending language. The use of jargon and scientific language was avoided.

-

Expert Panel

The principal investigator assembled a bilingual expert panel comprised of the translator of the original English tool, as well as two other health professionals. The panel had regular meetings to discuss the various aspects of translation. The first draft of the translated tool was critiqued and revised by each member. The panel strived to identify discrepancies between the forward translated questionnaire and its existing English version. Any issues pertaining to the clarity of expression were identified and corrected.

A monolingual group comprising of three individuals above 60 years of age, who were native Malayalam speakers and derived from the community, reviewed the forwarded translated script and gave their feedback, which was incorporated into the final draft.

-

Back translation

An independent translator, using the same outline as detailed in the first step, back-translated this questionnaire to English. The back translator had no prior familiarity with the questionnaire. The conceptual and cultural equivalence was taken into account, rather than the linguistic equivalence. Any discrepancies that arose were discussed with the principal investigator and the bilingual expert panel to make the questionnaire satisfactory.

Finally, all three versions of the GDS-30, namely, the original English questionnaire, as well as the translated and back-translated versions, were reviewed again to ensure the accuracy of the above procedural steps.

-

Pre-testing and cognitive interviewing

The pre-testing of this instrument was done on individuals aged sixty years and above, which comprised the target population. The participants were first screened to ensure that they were well versed in both languages and to rule out the presence of any underlying mental health issues that might interfere with the administration of the questionnaire.

The principal investigator conducted in-depth interviews on 100 elderly people belonging to both genders and varying socio-economic backgrounds, who regularly attended the elders' forum of our urban health-training center. These respondents were administered the questionnaire and were debriefed by asking them what they perceived the intention of each question to be and the meaning behind their choices. Their answers were compared to the actual responses on the questionnaire. The respondents were also asked to identify any words that they did not understand or found offensive or unacceptable. A list of alternative words was proposed in such cases, and they were asked to select the word that best conformed to their native language and cultural background.

-

Pilot Testing & Final Version

The questionnaire was administered to a group of individuals selected from the community at large, who fit the characteristics of the target population.

The aims were to ensure that the translated items retained the same meaning as the original items (semantic equivalence), to do away with any confusion concerning the content of each item, and to establish whether the concept it proposes to measure is relevant to the prevailing cultural setting. Debriefing was performed on the target population after the pilot testing. The requisite alterations were made depending upon their responses, to give shape to the final version.

All the stages of translation were serially numbered and documented.

Methodology of Validation

The principal investigator carried out a series of house visits in a rural community, to identify individuals aged 60 years and above, to whom the translated scale could be administered. After explaining the purpose of the visit to such persons and ascertaining their willingness to be interviewed, their written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained. Additionally, the Mini-Mental State Examination was administered before administering the GDS scale, to rule out cognitive impairment. Those who did not give consent were very infirm, or unable to communicate adequately were excluded from the study. Finally, a sample of 100 elderly individuals was interviewed for validation of the questionnaire.

These individuals were simultaneously assessed by a qualified doctor, who had received the necessary training from a consultant psychiatrist in the diagnosis of depressive disorders. This doctor evaluated the study subjects clinically using theInternational Classification of Diseases-tenth revision (ICD-10) criteria for the diagnosis of depression, which is considered as the gold standard.[14] The said doctor was unaware of the result of the initial screening done in these individuals by using the translated version of the GDS-30 questionnaire.

In this manner, the diagnostic performance of the translated questionnaire was assessed against the gold standard of clinical diagnosis.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the institutional research and ethics committee. Data were collected only after obtaining written informed consent from the respondents. The approval was granted on 1st April 2019.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS software, version 20.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

The translated version of the GDS-30 scale was administered to 100 elderly individuals (70 females and 30 males) between the ages of 60 and 87 years. The translated screening scale identified depression in 49 persons who had completed the questionnaire. The doctor who had been trained by the consultant psychiatrist to diagnose depressive disorders, and had simultaneously evaluated these individuals, diagnosed depression in 39 out of the 100 persons in the sample. In this manner, the diagnostic performance of the translated GDS-30 scale was compared to the clinical diagnosis made using the ICD-10 criteria (the gold standard).

Following the statistical analysis, the sensitivity of the Malayalam translation of the GDS-30 scale was calculated to be 87.20%, whereas the specificity was found to be 73.80%. The Cronbach's alpha and split-half reliability of the translated questionnaire were calculated to be 0.920 and 0.897 respectively. This implied a high level of internal consistency for the translated version of the scale.

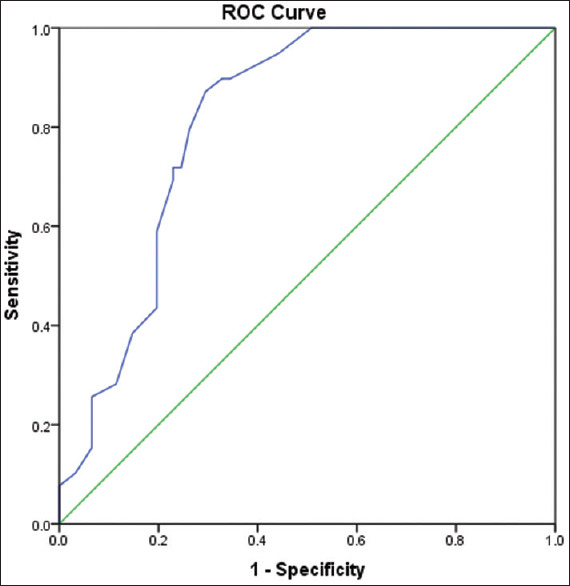

The result of the ROC analysis is shown in Figure 1. The area under the curve was calculated to be 0.814 (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Receiver-Operator Curve characteristics of the Malayalam translation of the GDS-30 scale

Table 1 depicts the result of the Youden index analysis that was used for confirmation of the findings of the ROC analysis. It was determined that the scale had a sensitivity of 0.87 and a specificity of 0.70 when applying a cut off of 9 and above on the questionnaire.

Table 1.

Sensitivity and specificity values for specific score cutoffs on the translated GDS-30 scale

| Cut off (≥) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s J |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| 1.50 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| 2.50 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 3.50 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| 4.50 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| 5.50 | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| 7.00 | 0.90 | 0.66 | 0.55 |

| 8.50 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 0.57 |

| 9.50 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.58 |

| 10.50 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.53 |

| 11.50 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.47 |

| 12.50 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.49 |

| 13.50 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.46 |

| 14.50 | 0.59 | 0.80 | 0.39 |

| 15.50 | 0.54 | 0.80 | 0.34 |

| 16.50 | 0.44 | 0.80 | 0.24 |

| 17.50 | 0.38 | 0.85 | 0.24 |

| 18.50 | 0.28 | 0.89 | 0.17 |

| 19.50 | 0.26 | 0.93 | 0.19 |

| 20.50 | 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.11 |

| 22.00 | 0.15 | 0.93 | 0.09 |

| 23.50 | 0.13 | 0.95 | 0.08 |

| 24.50 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.07 |

| 25.50 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.08 |

| 26.50 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.05 |

| 28.50 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.03 |

| 31.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

Discussion

The utility of a translated questionnaire depends not only on how closely it resembles the original version but also on cultural adaptations that need to be made to make the tool relevant to the socio-cultural background of the target population. Ensuring that the final version accomplishes both goals while adhering to globally recognized procedural recommendations for translation, can often be an arduous process fraught with challenges.[15]

The biggest hurdle that we faced in translating the GDS-30 questionnaire was in maintaining semantic equivalence, which requires each item in the questionnaire to have the same meaning as intended in the original version. The investigators found that a few questions in the original questionnaire were difficult to translate into Malayalam owing to a lack of equivalent words in the native tongue to convey the exact meaning. Difficulties were encountered in translating the following expressions: “basically satisfied with your life”, “wonderful to be alive”, “restless and fidgety”, “downhearted and blue”. We used words closest in meaning to communicate the idea.

Content equivalence was also an issue in a few instances. Establishing this required each statement to be scrutinized, to determine its relevance in the prevailing cultural milieu. For instance, the phrase “do you think it is wonderful to be alive now” posed some difficulty in communicating the general idea behind the question, owing to the different cultural backgrounds of the respondents. The concept of happiness in being alive in this day and age was difficult to grasp for those belonging to economically weaker sections of society, who live from one day to the next. Difficulties were also encountered in the questions: ”are you in good spirits most of the time” and “do you feel full of energy”, as respondents found it difficult to grasp the slight differences in meaning between the two.

Indeed, it has been recorded in the literature that maintaining semantic and content equivalence are the most difficult aspects of translation of scientific questionnaires.[15,16] At the same time, this is also the ultimate test of the quality and effectiveness of the translated tool. We found that the higher literacy levels in Kerala, coupled with the familiarity of the population with the English language, simplified the process of translation, despite challenges in other areas.

The diagnostic and psychometric properties of the Malayalam translation of the GDS-30 were noted to be good. The high internal consistency that we obtained in our study is comparable to that reported in the original study by Yesavage et al.[11] The Malayalam translation of the scale was found to have a high sensitivity of 87.2%, which is akin to the similar value of 89% obtained by Tang et al. in the Chinese version of the GDS-30.[17] The specificity of 73.8% that we obtained in our study was lower than that of the Kannada translation of the GDS-30 but higher than that of the Tamil translation.[7,8]

Previous studies have determined that an adequate screening questionnaire for depression should have sensitivity and specificity of at least 70%.[18] By that standard, the Malayalam translation of the GDS-30 questionnaire is a valid screening instrument that can be utilized effectively to detect depression in the general population.

Depression, especially in vulnerable populations like the elderly, is a growing issue that needs to be addressed. However, a large number of cases that present with non-specific symptoms to primary care physicians are often missed. Questionnaires can be invaluable in such settings to identify cases for initial management and to ensure a timely referral to specialist services. There is a need for standard questionnaires to be translated appropriately into regional languages for use in local communities. The translated and validated version of the GDS-30 would be a step toward the recognition and further management of depression in Kerala and can also be an invaluable tool to drive further research on the subject of geriatric depression.

The Malayalam version of the GDS-30 is a reliable and valid screening tool for diagnosing depression in the elderly population of the state of Kerala. Our study represents the first undertaking of its kind to translate and validate the GDS-30 from its original English version to Malayalam. The translated questionnaire was found to have good psychometric qualities that are comparable to translations in other Indian languages. Ultimately, this would be a valuable asset for primary care physicians that could assist in the early diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

No external grants were availed for the purpose of this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

GDS-30 Malayalam Translated Questionnaire

References

- 1.Fiske A, Wetherell J, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:363–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilania M, Yadav V, Bairwa M, Behera P, Gupta S, Khurana H, et al. Prevalence of depression among the elderly (60 years and above) population in India, 1997–2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:832. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7136-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao G, Pathak K, Singh L, et al. NIMHANS Publication; 2016. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Summary. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg K, Kumar CN, Chandra PS. Number of psychiatrists in India: Baby steps forward, but a long way to go. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:104–5. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pattanayak RD, Sagar R. Depressive disorders in indian context: A review and clinical update for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62:827–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, Leplège A, Sullivan M, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:913–23. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajgopal J, Sanjay TV, Mahajan M. Psychometric properties of the geriatric depression scale (Kannada version): A community-based study. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2019;6:84–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar S, Kattimani S, Roy G, Premarajan KC, Sarkar S. Validation of the Tamil version of short-form Geriatric Depression Scale-15. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6:442–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.158800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai ND, Shah SN, Sharma E, Mishra A, Mehta K. Validation of Gujarati version of 15-item geriatric depression scale in elderly medical outpatients of general hospital in Gujarat. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:1453–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahiri A, Chakraborty A. Psychometric validation of geriatric depression scale – short form among bengali-speaking elderly from a rural area of West Bengal: Application of item response theory. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64:109–15. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_162_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatric Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. NY: The Haworth Press, Inc; 1986. pp. 165–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO | Process of translation and adaptation of instruments [Internet]. Who.int. 2020. cited 31 October 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 14.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menon D, Venkateswaran C. The process of translation and linguistic validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-brain quality of life instrument from English to Malayalam: The challenges faced. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:300–5. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_36_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karthikeyan G, Manoor U, Supe S. Translation and validation of the questionnaire on current status of physiotherapy practice in the cancer rehabilitation. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:29–36. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.146117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang W. Can the geriatric depression scale detect post-stroke depression in Chinese elderly.? J Affect Disord. 2004;81:153–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah A, Phongsathorn V, George C, Bielawska C, Katona C. Psychiatric morbidity among continuing care geriatric inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1992;7:517–25. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

GDS-30 Malayalam Translated Questionnaire