Abstract

Leukemia cutis (LC) is a term describing skin lesions caused by cutaneous infiltration by hematological malignancies (myeloid or lymphoid). To our knowledge, there are no published reports on dermoscopic presentation of LC. The aim of the study was to analyze dermoscopic pattern in series of 5 patients with the diagnosis of LC.

Key Words: Chloroma, dermatoscopy, dermosopy, leukemia cutis, myeloid sarcoma

Introduction

Leukemia cutis (LC) is a term describing skin lesions caused by cutaneous infiltration by hematological malignancies (myeloid or lymphoid). Cutaneous involvement concerns 2-30% of patients with leukemia, and occurs more commonly in the course of acute leukemia (10–15% of all cases is acute myeloid leukemia), usually in patients with a previously diagnosed malignancy. In a patient with chronic myeloproliferation the presence of skin infiltration may be an initial sign of blastic transformation and heralds a progression of the disease.[1,2] LC presents a wide clinical spectrum. The diagnosis is based on a patient's medical history, histopathological, and immunohistochemical evaluation of skin samples.[1] We have found no original studies on leukemia cutis with regard to population from East-Central Europe. To the best of our knowledge, there are also no published reports on the dermoscopic presentation of LC.

Case Series Report

All patients from the study group have been consulted in the Department of Dermatology or Dermatology Outpatient Clinic between May 2016 and May 2018. There were two females and three males, aged 49–70. Four out of the five patients were referred by a hematologist, one—by a surgeon (in the latter cutaneous manifestation was the first sign of a hematological malignancy). All patients had dermoscopic examination performed with Fotofinder videodermoscope (×20 magnification, with ultrasound gel as an immersion fluid). In all cases the diagnosis of LC was confirmed histopathologically. Dermoscopic features were analyzed according to a standardized dermoscopic terminology by International Dermoscopy Society.[3]

The clinical characteristics of the studied patients are presented in Table 1. Figures 1 and 2 show clinical and dermoscopic features of the presented patients. In four cases (Patients 2, 3, 4, 5) dermoscopy showed the presence of polymorphic vascular pattern with the presence of dotted vessels, linear curved vessels and linear vessels with branches. In one case (Patient 1) dermoscopy showed the presence of diffuse pink–brownish structureless area. In four patients skin involvement occurred after the diagnosis of leukemia. In one patient (Patient 3; AML with myelodysplasia) LC was the first sign of a hematological malignancy.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the studied patients

| Patient | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Clinical presentation | Time between leukemia diagnosis and the presentation of leukemia cutis | Other, extramedullary presentation of leukemia | The survival time from the presentation of LC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

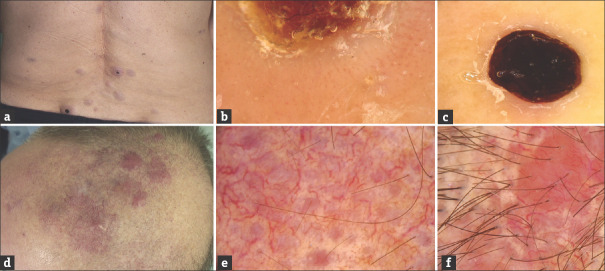

| 1 (Fig. 1 A-B) | M | 49 | Acute monocytic leukemia | Single brownish tumour of the right lower leg | 6 months | No | alive after 10-month follow-up |

| 2 (Fig. 1 C-D) | F | 64 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Violaceous plaque in the abdominal region | 5 years | No | alive after 3-month follow-up |

| 3 (Fig. 1 E-F) | M | 70 | Acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia | Giant tumour of the left lower leg (myeloid sarcoma) | the occurrence of the tumour preceded the leukemia diagnosis by 8 months | No | died after 12 months |

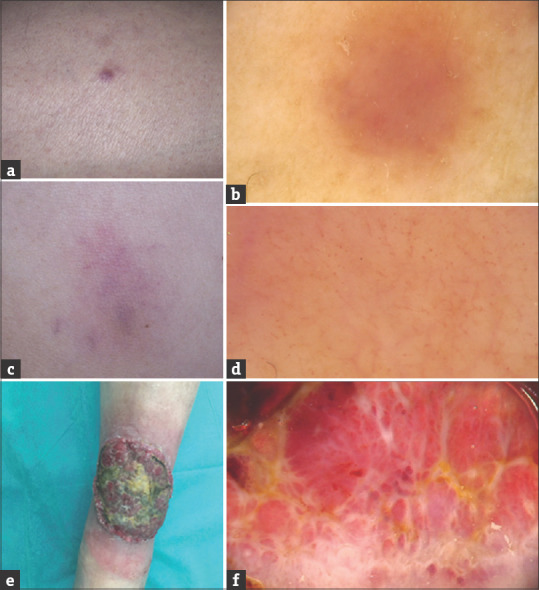

| 4 (Fig. 2 A-C) | F | 67 | Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | Multiple pink-brownish tumours, some with central necrotic crust, in the lumbar region | 8 months | No | died after 1 month |

| 5 (Fig. 2 D-F) | M | 65 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Coalescing tumours and plaques of the parietal region of the scalp | 14 years | No | alive after 13-month follow-up |

F: Female, M: Male

Figure 1.

(a and b) LC in the course of acute monocytic leukemia (Patient 1). Single brownish tumor of the right lower leg (a); Dermoscopy shows diffuse pink–brownish structureless area (b). (c and d) LC in the course of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (Patient 2). Violaceous plaque in the abdominal region (c); Dermoscopy shows polymorphic vascular pattern with the presence of dotted vessels, linear curved vessels, and linear vessels with branches as well as subtle structureless yellowish-orange areas in patchy distribution (d). (e and f) LC in the course of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Patient 3). Giant tumor of the left lower leg (e); Dermoscopy shows vascular areas containing polymorphic vascular pattern with the presence of dotted vessels, linear curved vessels, and linear vessels with branches on the pink-red structureless background intersected with white thick lines arranged in network-like structure and yellow-red structureless areas corresponding with the presence of a crust (f)

Figure 2.

(a-c) LC in the course of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (Patient 4). Multiple pink-brownish tumors, some with central necrotic crust, in the lumbar region (a); Dermoscopy shows the presence of polymorphic vessels on the whitish structureless background which surround central yellow-red structureless area corresponding with the presence of a crust (b). Within the lesions with central necrotic crust (black structureless area), peripheral vascular pattern was absent (c). (d-f) LC in the course of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Patient 5). Coalescing tumors and plaques of the parietal region of the scalp (d); Dermoscopy shows the presence of polymorphic vascular pattern with the predominance of linear vessels with branches of large diameter on the background consisting of pink, round structureless areas intersected with white structureless areas; additionally subtle structureless yellowish-orange areas in random distribution may be observed (e and f)

Discussion

LC presents wide clinical spectrum. Initially, it presents most commonly as single or multiple, nodular or papular skin eruptions. The cutaneous infiltrates may also occur within scars, post-traumatic areas or catheter sites.[1,2] The involvement of mucous membranes is observed quite rarely. In some cases leukemia cutis has a peculiar clinical presentation, appearing as leontine facies or chloroma. The differential diagnosis of LC includes non-specific skin lesions—leukemids. They occur in 25–40% of patients with leukemia and may be the result of associated cytopenia, adverse reactions to the recommended treatment or represent paraneoplastic syndromes.[2] The presence of LC is considered a predictor of poor prognosis. The survival time after its diagnosis varies among different studies, but most patients do not survive more than 12 months.[4,5]

The role on dermoscopy in dermatological diagnostics is constantly increasing. Nevertheless, the method has its limitations and dermoscopic image should always be interpreted in the clinical context. During the assessment of non-pigmented skin tumor—vascular morphology, vessels arrangement as well as additional clues are analyzed. The polymorphic vascular pattern is defined as the presence of two or more morphological types of vessels. In non-melanocytic skin tumors it is considered among signs of malignancy.[6] It has been described in amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous metastases, porocarcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma.[7,8,9] On the other hand, it may be encountered also in benign tumors, including irritated seborrheic keratosis, adnexal tumors, dermatofibroma, Clark's nevus, Miescher's nevus, pilomatrixoma.[7]

The presence of yellowish-orange structureless areas may be observed in cutaneous granulomatous disorders, xantogranulomas, pseudolymphomas, primary cutaneous lymphomas, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, Zoon balanitis, as well as in papular syphiloderm.[10]

All new-onset single or multiple non-typical skin lesions in a patient with leukemia should be suspected of LC. Dermoscopic presentation of LC seems to be variable and not characteristic. In the present case series the common dermoscopic feature (that occurred in 4 out of 5 cases) was the presence of polymorphic vascular pattern.

Histopathological evaluation is considered obligatory for non-pigmented lesions revealing the presence of polymorphous vessels and those that have a nonspecific dermoscopic features.[8] It seems that this approach is helpful in clinical follow-up of a patient diagnosed with a hematological malignancy and identifies, inter alia, the suspicious lesions from the spectrum of LC.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we presented dermoscopic features of LC for the first time. Our observations are in line with previous studies and confirm that LC may be the first sign of hematological malignancy or blastic transformation in a patient with previously diagnosed chronic leukemia.

The main limitation of the study is the small number of patients examined—the study is being continued in our Department.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, Schulz A, Sachse MM. Leukemia cutis - epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130–42. doi: 10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Errichetti E, Zalaudek I, Kittler H, Apalla Z, Argenziano G, Bakos R, et al. Standardization of dermoscopic terminology and basic dermoscopic parameters to evaluate in general dermatology (non-neoplastic dermatoses): An expert consensus on behalf of the International dermoscopy society. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:454–67. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, Lee JY, Kim HO, Cho BK, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:614–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su WP. Clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical correlations in leukemia cutis. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zalaudek I, Kreusch J, Giacomel J, Ferrara G, Catricalà C, Argenziano G. How to diagnose nonpigmented skin tumors: A review of vascular structures seen with dermoscopy: Part II. Nonmelanocytic skin tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:377–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum A, Metzler G, Bauer J. Polymorphous vascular patterns in dermoscopy as a sign of malignant skin tumors. A case of an amelanotic melanoma and a porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 2005;210:58–9. doi: 10.1159/000081486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martín JM, Bella-Navarro R, Jordá E. Vascular patterns in dermoscopy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:357–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME, Deng L, Busam KJ, Myskowski PL. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429–33. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermatoscopy of granulomatous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]