Abstract

Background:

Extramammary Paget's disease (EMPD) is a rare skin cancer and sometimes has fatal prognosis. For progressive cases, therapeutic options are limited. In recent years, treatment with an anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody has improved the prognosis of various malignancies. In addition, correlations between PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in tumor cells and favorable responses to anti-PD-1 therapy have been reported for several cancers. There have been a few case series of analysis of PD-L1 expression in patients with EMPD.

Aims:

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between the EMPD and PD-L1/PD-1 expression in Japanese EMPD patients.

Materials and Methods:

We investigated 39 patients with EMPD by immunohistochemical staining of PD-L1 and PD-1. We counted the number of tumor cells that were positive for PD-L1 and the number of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells (TIMCs) that were positive for PD-L1 and PD-1. We also analyzed correlations between the expression of PD-L1 and PD-1 in EMPD and patients’ characteristics.

Results:

We found that none of the Paget's cells expressed PD-L1. All of the specimens contained TIMCs, and some of the TIMCs expressed PD-L1 and PD-1. However, there was no correlation between the expression of PD-L1/PD-1 in TIMCs and patients’ characteristics.

Conclusion:

Although tumor cells did not express PD-L1 and the expression of PD-L1/PD-1 in TIMCs did not correlate with patients’ characteristics, future clinical studies should be carried out to explore another immune escape pathway in EMPD.

Key Words: Extramammary Paget's disease, programmed death-1, programmed death-ligand 1, tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells

Introduction

Extramammary Paget's disease (EMPD) is a rare skin cancer that mainly occurs in the vulva, perineum, penis, scrotum, and perianal regions.[1] Most patients receive wide local excision, and some patients may receive sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymph node dissection.[2] However, it has been reported that distant metastasis occurred in 2.5% of EMPD patients.[3] Patients with metastatic EMPD have been treated with 5-fluorouracil-based or taxane-based regimens, but no randomized trial of these therapies has been reported.[4,5] Thus, treatment options for patients with unresectable EMPD are limited, and further treatments are needed to improve the poor prognosis of patients with distant metastasis.

Recently, anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody immunotherapy has shown improvement in the prognosis of several malignancies including melanoma, lung cancer, and other cancers.[6,7] Recent studies have shown that the expression of PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in tumor cells correlates with a favorable response to anti-PD-1 therapy and is one of the predictors of outcome of cancer treatments.[6] In addition, previous studies have shown that PD-L1 and PD-1 are expressed in tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells (TIMCs), and their expression is correlated with the prognosis of patients with malignancies.[8,9] The use of immunocheckpoint inhibitors, including an anti-PD-1 antibody, is also a promising therapy for patients with unresectable EMPD. In a recent study, Karpathiou et al. found that there was no expression of PD-L1 in 22 EMPD patients in France.[10] However, data for PD-L1 expression in EMPD in Asian patients are lacking, and there has been no study in which PD-1 expression in TIMCs of EMPD patients was investigated. Here, we describe the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and the expression of PD-L1 and PD-1 in TIMCs of Japanese patients with EMPD.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Thirty-nine patients with EMPD (21 men and 18 women, median age: 75 years, mean age: 58–92 years) were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of EMPD was made on the basis of the reported criteria in Table 1.[1,11] The patients were divided into two groups: 16 patients with dermal invasion and 23 patients with in situ lesions. The patients were also divided into groups according to sex and age. This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tottori University Faculty of Medicine, Japan (No. 17A076). Informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease

| Frequently affected site |

| Vulva |

| Perineal |

| Perianal |

| Penile |

| Clinical presentation |

| Red or brown plaque |

| Hypopigmentation |

| Erosion or ulceration |

| Nodule |

| Itching |

| Histopathological presentation |

| Proliferation of Paget’s cells (abundant pale cytoplasm and large nuclei) with nested or single-cell pattern |

| Spreading along the skin appendages |

| Invasion into the dermis |

| Special staining |

| Positive for PAS and alcian blue |

| Immunohistochemistry |

| Positive for CEA, CAM 5.2, CK7, and GCDFP15 |

| Negative for CK20, S100 protein, and melanocytic markers (Melan-A, HMB45, etc.) |

PAS: Periodic acid–Schiff, CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen, CK7: Cytokeratin 7, GCDFP15: Gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, CK20: Cytokeratin 20

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded 4-μm-thick sections of specimens were used for immunohistochemical staining and hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining. Immunohistochemical staining of PD-L1 and PD-1 was performed as reported previously using Roche Biomedical Ventana antibodies (PD-L1: SP263, PD-1: NAT105).[12] Both PD-L1 and PD-1 assays were performed with the manufacturer's specifications for the Ventana Ultraview system (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Normal lymph nodes were stained with PD-L1 and PD-1 antibodies as positive controls. The percentage of PD-L1-positive tumor cells and the percentages of PD-L1- and PD-1-positive TIMCs were calculated. The distinction between TIMCs and tumor cells was made by comparing H and E and immunohistochemical staining specimens.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney test was used for analysis of the correlation of PD-L1 or PD-1 expression. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Patients’ backgrounds

Data for patients are shown in Table 2. The genital region was the most commonly affected area (89.7%), and the axilla was affected in only 4 (10.3%) of the 39 patients. Sixteen patients (41.0%) had invasive EMPD and 23 patients (59.0%) had EMPD in situ. All patients received one of the following three types of cancer treatment: surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. There was no patient treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Among patients, two patients had lymph node metastasis, three patients had lymph node and distant metastasis, and two patients had distant metastases without lymph node metastasis. Five patients died of the disease with distant metastases.

Table 2.

Clinical summary of patients enrolled in this study

| Characteristics | Patients (n=39), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years old) | |

| Average | 75.1 |

| Median | 75 |

| Range | 58-92 |

| ≤75 | 20 (51.3) |

| >75 | 19 (48.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 21 (53.8) |

| Female | 18 (46.2) |

| Primary lesion | |

| Genital | 35 (89.7) |

| Axilla | 4 (10.3) |

| Histopathological type | |

| In situ | 23 (59.0) |

| Invasive | 16 (41.0) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | 36 (92.3) |

| Radiotherapy | 4 (10.3) |

| Chemotherapy | 5 (12.8) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 5 (12.8) |

| Distant metastasis | 5 (12.8) |

Expression of programmed death-ligand 1 in tumor cells

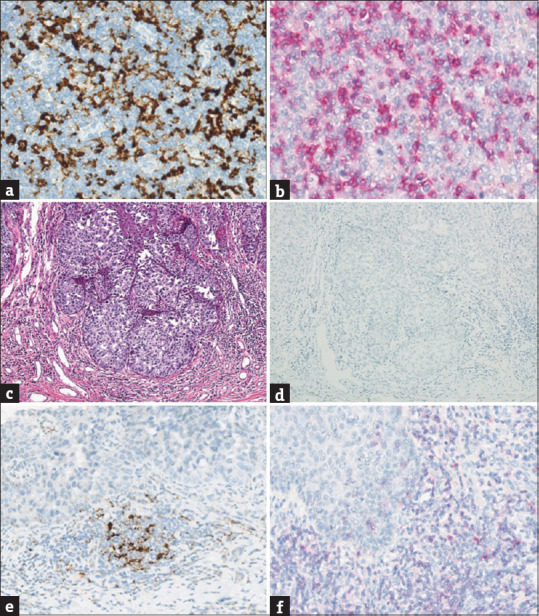

As positive controls, normal lymph nodes were stained with PD-L1 and PD-1 antibodies, and both specimens showed a positive expression of PD-L1 and PD-1 in lymphocytes in lymph nodes [Figure 1a and b]. However, tumor cells of all the 39 patients were negative for PD-L1, and representative figures are shown in Figure 1c and d.

Figure 1.

(a) Positive control for programmed death-ligand 1 staining using normal lymph nodes (×400). Positive cells are stained brown. (b) Positive control for programmed death-1 using normal lymph nodes (×400). Positive cells are stained red. (c) A representative picture of tumor cells of extramammary Paget's disease (H and E, ×100). (d) Result of the programmed death-ligand 1 staining in the same paraffin-embedded specimen of c (×100). No tumor cell was stained with the programmed death-ligand 1 antibody. (e) Tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells were partially positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (×200). (f) Tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells were partially positive for programmed death-1 (×200)

Expression of programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-1 in tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells

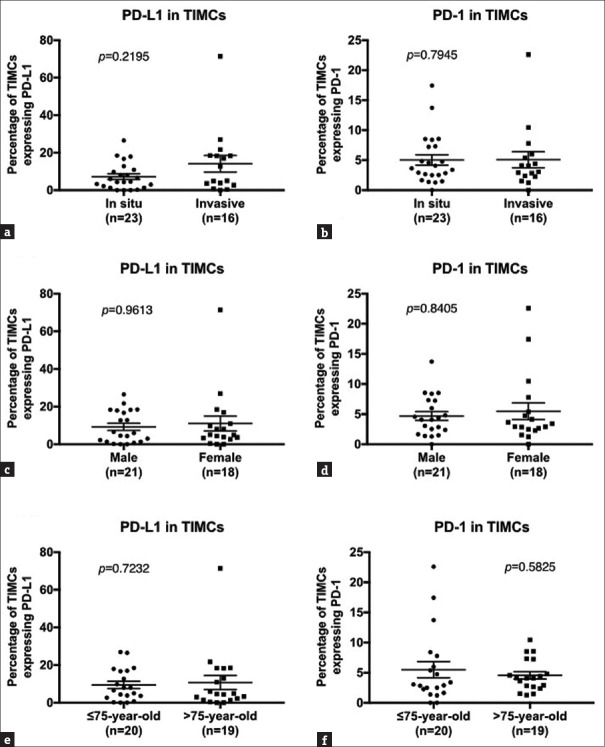

TIMCs were partially positive for PD-L1 and PD-1 antibodies [Figure 1e and f]. We then performed correlation analysis among the following groups: PD-L1 (P = 0.2195) and PD-1 (P = 0.7945) expression of TIMCs in the dermal invasion group and in situ group [Figure 2a and b], PD-L1 (P = 0.9613) and PD-1 (P = 0.8405) expression of TIMCs in males and females [Figure 2c and d], and PD-L1 (P = 0.7232) and PD-1 (P = 0.5825) expression of TIMCs in the group of patients aged 75 years or younger and the group of patients older than 75 years of age [Figure 2e and f]. No significant differences were found between the groups.

Figure 2.

(a) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (P = 0.2195) in the in situ group and invasive group. (b) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells expressing programmed death-1 (P = 0.7945) in the in situ group and invasive group. (c) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (P = 0.9613) in males and females. (d) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (P = 0.8405) in males and females. (e) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (P = 0.7232) in the group of patients aged 75 years or younger and the group of patients older than 75 years of age. (f) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (P = 0.5825) in the group of patients aged 75 years or younger and the group of patients older than 75 years of age; error bar shows the standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 was statistically significant

Discussion

The expression of PD-L1 has been evaluated in various tumors including breast cancer, lung cancer, malignant melanoma, and other cancers.[6,7,12] These tumor cells take advantage of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway to escape the immune system.[13] Thus, blockade of this pathway has been expected to be a promising clinical outcome of cancer immunotherapies targeting a wide spectrum of solid and hematogenic malignancies.

We found that Paget's cells did not express PD-L1 as was found in a study in French patients.[10] However, Fujimura et al. reported that three of six EMPD patients expressed PD-L1.[14] According to our results and results of those previous studies, we considered that the expression of PD-L1 is extremely rare for EMPD, and that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is not mainly involved in EMPD and tumor cells may use other immune escape pathways in EMPD.

The expression levels and clinical significance of PD-L1 and PD-1 in TIMCs are still unknown. According to a previous report, patients with urothelial carcinoma in whom PD-L1 was expressed in TIMCs had longer survival than that of patients without PD-L1 expression.[8] The authors considered that the expression of PD-L1 in TIMCs shows a tumor antigen-specific immune response. On the other hand, the functional significance of PD-1 expression in TIMCs is also still unknown, and there were two controversial reports with regard to the prognostic significance of PD-1 expression in TIMCs.[9,15] In our study, all the 39 specimens had TIMCs around the tumor. We calculated the percentage of TIMCs expressing PD-L1 and PD-1 and examined whether there was a significant difference between the group of tumors invading the dermis and the group of in situ EMPD. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups, indicating that the percentage of TIMCs expressing PD-L1 and PD-1 may not be associated with tumor invasion in EMPD.

Currently, a major factor determining tumor progression is the characteristic of T-cells within TIMCs.[16] Exhaustion-associated molecules on T-cells such as LAG3, 2B4, and TIM3 are considered to be the mechanism of tumor development.[16] Inhibitor interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α secretion by T-cells is also linked with T-cell exhaustion.[16,17] Therefore, the investigation of the interaction of tumor and TIMCs is expected to provide new insights into cancer immunotherapy.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that there was no expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells, and that there was no correlation between the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in TIMCs and invasion of EMPD in Japanese patients. However, we still cannot rule out the possibility of an immunocheckpoint inhibitor being a therapeutic option. Further studies are needed to explore another immune escape pathway in EMPD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget's disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura Y, Fujisawa Y, Ishikawa M, Nakamura Y, Ishitsuka Y, Maruyama H, et al. Usefulness of sentinel lymph node biopsy for extramammary Paget disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:954–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karam A, Dorigo O. Treatment outcomes in a large cohort of patients with invasive extramammary Paget's disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshino K, Fujisawa Y, Kiyohara Y, Kadono T, Murata Y, Uhara H, et al. Usefulness of docetaxel as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic extramammary Paget's disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:633–7. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tokuda Y, Arakura F, Uhara H. Combination chemotherapy of low-dose 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced extramammary Paget's disease. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:194–7. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, Hodi FS, Gutzmer R, Neyns B, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375–84. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gettinger S, Rizvi NA, Chow LQ, Borghaei H, Brahmer J, Ready N, et al. Nivolumab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2980–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellmunt J, Mullane SA, Werner L, Fay AP, Callea M, Leow JJ, et al. Association of PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells and overall survival in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:812–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badoual C, Hans S, Merillon N, Van Ryswick C, Ravel P, Benhamouda N, et al. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:128–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karpathiou G, Chauleur C, Hathroubi S, Habougit C, Peoc’h M. Expression of CD3, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in mammary and extra-mammary Paget disease. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1297–303. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget's disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543–53. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1457955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karnik T, Kimler BF, Fan F, Tawfik O. PD-L1 in breast cancer: Comparative analysis of 3 different antibodies. Hum Pathol. 2018;72:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarhini AA, Zahoor H, Yearley JH, Gibson C, Rahman Z, Dubner R, et al. Tumor associated PD-L1 expression pattern in microscopically tumor positive sentinel lymph nodes in patients with melanoma. J Transl Med. 2015;13:319. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0678-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimura T, Kambayashi Y, Kakizaki A, Furudate S, Aiba S. RANKL expression is a useful marker for differentiation of pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ from extramammary Paget disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:772–5. doi: 10.1111/cup.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JR, Moon YJ, Kwon KS, Bae JS, Wagle S, Kim KM, et al. Tumor infiltrating PD1-positive lymphocytes and the expression of PD-L1 predict poor prognosis of soft tissue sarcomas. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24:541–50. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koeck S, Kern J, Zwierzina M, Gamerith G, Lorenz E, Sopper S, et al. The influence of stromal cells and tumor-microenvironment-derived cytokines and chemokines on CD3+CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocyte subpopulations. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1323617. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1323617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]