Heart failure (HF) mortality rates are disproportionately rising among racial/ethnic groups of color who may be eligible for heart transplant (HT).1 Among the age group receiving the majority of HT in the U.S. (aged 35–64 years), HF mortality rates of African-American patients are 2.6-fold higher than White patients.1 Over the past decade, racial/ethnic groups of color represented 36% of U.S. adult HT recipients2 and 40% of the U.S. population. It is unclear whether states vary in ratio of HT rate to HF mortality rate by race/ethnicity. Since structural inequalities related to bias and organizational culture may contribute to disparities in HT allocation,3,4 it is important to identify geographic areas with gaps in care so that structural interventions may be designed to reduce existing disparities.

Using data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research (CDC Wonder) we examined racial/ethnic disparities in HT and HF mortality [ICD 10: I50(I50.0, I50.1, I50.9)] by state from 2016–2018. We included administratively described non-Hispanic African-American, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic White patients aged 35–64 years. National analyses included all 50 states plus D.C. In state analyses, states were excluded for missing HF mortality (n=39 + D.C. Hispanic patients, n=20 +D.C. African-American patients) which was suppressed by CDC Wonder for <20 HF deaths or risk of identifying patients. National cohorts included 19,237 HF deaths and 5,502 HT; state cohorts included 17,899 HF deaths and 4,859 HT among African-American (n=30 states), Hispanic (n=11 states), and White patients. The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review. All data are publicly available at UNOS and CDC Wonder sites.

The primary outcome was HT rate to HF mortality rate ratio. Ratios were calculated for each race/ethnicity for the U.S. and by state as the number of HT per 100,000 population divided by the age-adjusted HF mortality rate per 100,000 population. HT to HF mortality ratios were compared among non-Hispanic African-American versus non-Hispanic White patients and Hispanics versus non-Hispanic White patients. We treat the HT to HF mortality ratio for White patients as the expected ratio for African-American and Hispanic patients. A ratio for African-American or Hispanic versus White patients was considered lower than expected for values <0.90, as expected for values between 0.90–1.10 (1 represented equal ratio of HT to HF mortality between groups with a reasonable interval of +/−0.1), and higher than expected for values >1.10. Analyses were completed using R version 3.6.3 (Vienna, Austria).

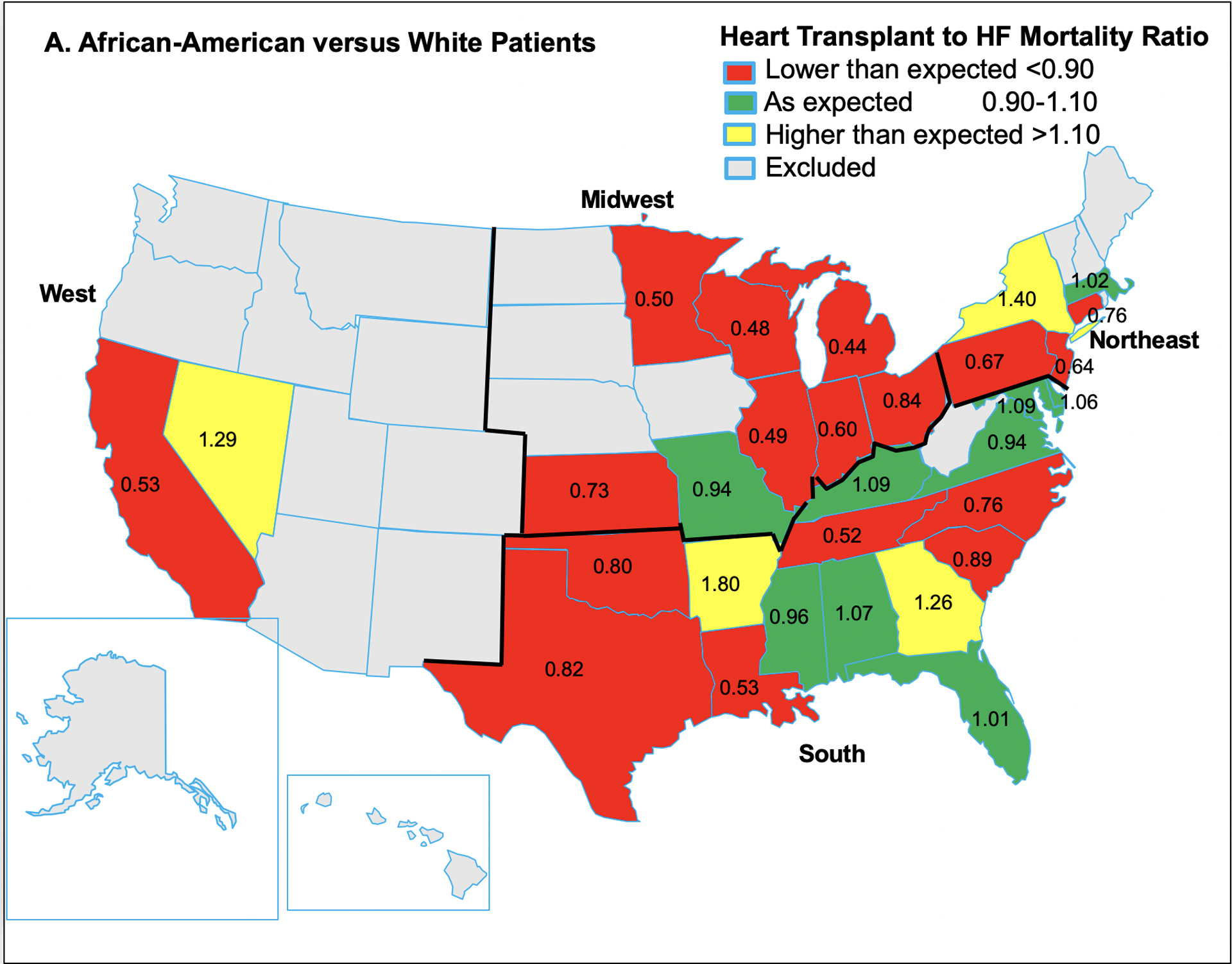

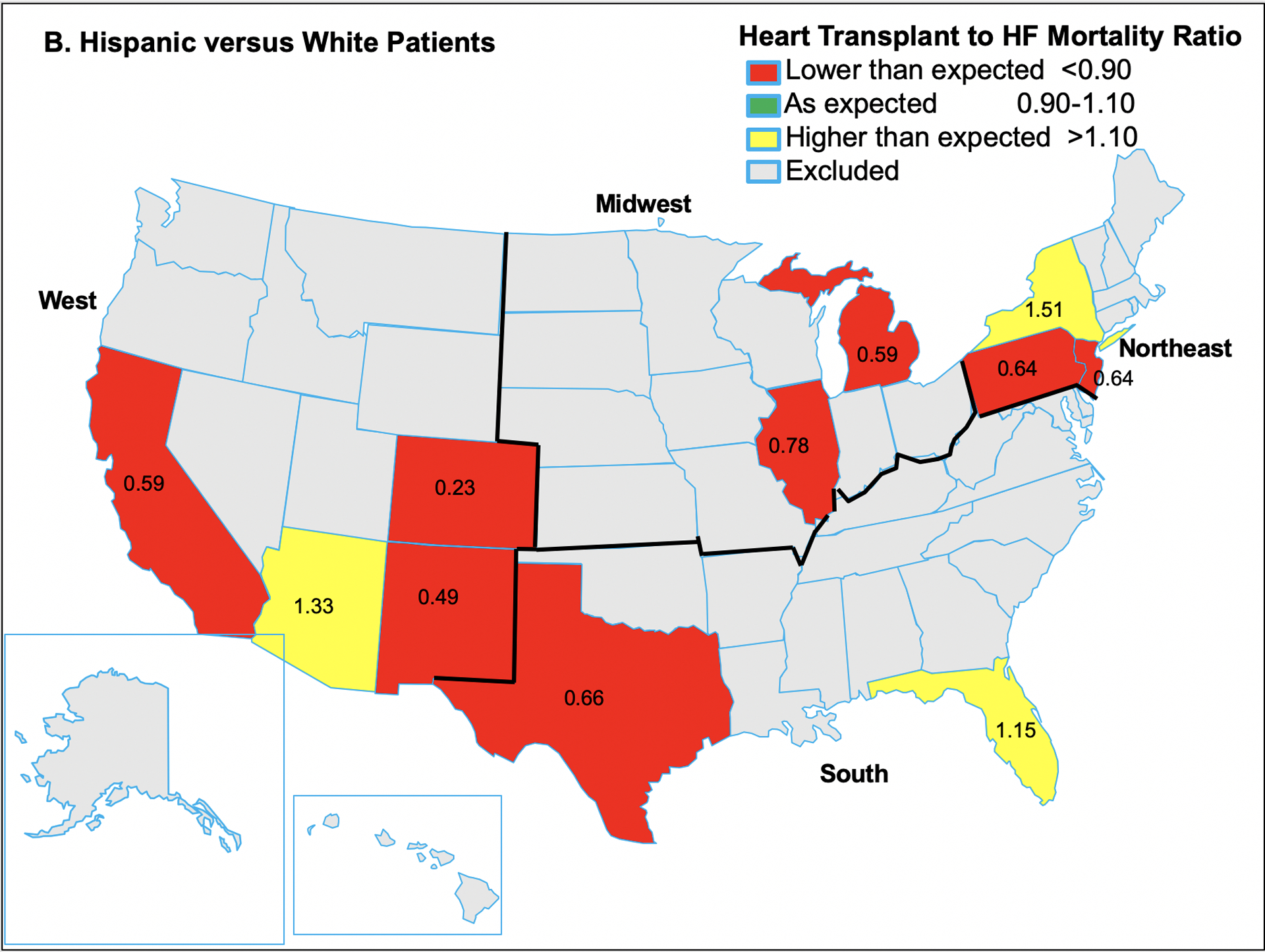

Compared with White patients in national analyses, the ratio was lower than expected at 0.67 (0.28 HT to HF mortality African-American/0.41 HT to HF mortality White) for African-American patients and as expected at 0.92 (0.38 Hispanic/0.41 White) for Hispanic patients. Among the 30 states included for African American patients, 17 (57%) had lower than expected ratios, 9 (30%) as expected ratios, and 4 (13%) higher than expected ratios (Figure A). The median ratio was 0.83 (IQR 0.61–1.05). States with the lowest ratios (≤0.50, Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota) were clustered in the upper Midwest. Among the 11 states included for Hispanic patients, 8 (73%) had lower than expected ratios, and the remaining 3 (27%) had higher than expected ratios (Figure B). The median ratio was 0.64 (IQR 0.59–0.96). States with the lowest ratios (≤0.50, Colorado and New Mexico) were both Southwestern states; however, Arizona, another Southwestern state had a higher than expected ratio.

Figure. Ratio of Heart Transplant to Heart Failure Mortality By Race and Ethnicity from 2016–2018.

The heart transplant to heart failure mortality ratios for African-American versus White patients are indicated in Panel A, and Hispanic versus White patients in Panel B. Red indicates lower than expected ratio <0.90; green, as expected 0.90–1.10; yellow, higher than expected >1.10.

This study provides a starting point to examine racial/ethnic and geographic differences in HT to HF mortality. Given known differences in social determinants of health and structural inequalities in clinical treatment decisions among racial/ethnic patients of color,3,4 transplant centers in states with lower than expected ratios should consider how results reflect their practices. These data may help centers establish metrics for racial/ethnic equity in HT allocation.

As crude analyses, results should be interpreted with caution since granular factors such as HF phenotype, socioeconomic factors, and comorbidities were not available for adjustment in analyses. Although HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is not defined in CDC Wonder, HF mortality rate is an approproriate proxy for end-stage HF. HFrEF is the most common form of HF requiring hospitalization among African-American and White patients, and annual HFrEF to HF with preserved EF mortality rate ratios are higher among African-American than White patients.5 Racial/ethnic disparities observed in this study may also be underestimated by lack of death certificates for undocumented immigrants in CDC Wonder.

Among U.S. 35–64 year olds, HT to HF mortality ratio was lower for African-American than White patients. State analyses revealed greatest disparities in the Midwest. The overall HT to HF mortality ratio was similar among Hispanic and White patients, but among states with 20 or more HF death among Hispanic patients, the majority of states across regions had lower HT to HF mortality ratio for Hispanic compared with White patients. Future interventions should focus on states with more profound disparities in HT allocation.

Funding Sources:

Dr. Breathett has research funding from Women As One Escalator Award; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) K01HL142848, R25HL126146 subaward 11692sc, and L30HL148881; University of Arizona Health Sciences, Strategic Priorities Faculty Initiative Grant; University of Arizona, Sarver Heart Center, Novel Research Project Award in the Area of Cardiovascular Disease and Medicine, Anthony and Mary Zoia Research Award; and American Heart Association (AHA) Get With the Guidelines Young Investigator Database Seed Grant Award. Dr. Carnes’s research on scientific workforce diversity is funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) R35GM122557.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: none

References

- 1.Glynn P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Feinstein MJ, Carnethon M, Khan SS. Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Related to Heart Failure in the United States. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73:2354–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colvin M, Smith JM, Hadley N, Skeans MA, Uccellini K, Goff R, Foutz J, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL. OPTN/SRTR 2018 Annual Data Report: Heart. American Journal of Transplantation. 2020;20:340–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Yee R, Knapp SM, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera-Theut K, Zabala L, Stone J, McEwen MM, Calhoun E, Sweitzer NK. Association of Gender and Race with Allocation of Advanced Heart Failure Therapies. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Knapp S, Larsen A, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera-Theut K, Zabala L, Stone J, McEwen MM, Calhoun E, Sweitzer NK. Does Race Influence Decision Making for Advanced Heart Failure Therapies? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang PP, Wruck LM, Shahar E, Rossi JS, Loehr LR, Russell SD, Agarwal SK, Konety SH, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond WD. Trends in Hospitalizations and Survival of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in Four US Communities (2005–2014): The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Community Surveillance. Circulation. 2018;138:12–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]