Abstract

Context

Bone mineral density (BMD) decreases rapidly during menopause transition (MT), and continues to decline in postmenopause.

Objective

This work aims to examine whether faster BMD loss during the combined MT and early postmenopause is associated with incident fracture, independent of starting BMD, before the MT.

Methods

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, a longitudinal cohort study, included 451 women, initially premenopausal or early perimenopausal, and those transitioned to postmenopause. Main outcome measures included time to first fracture after early postmenopause.

Results

In Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusted for age, body mass index, race/ethnicity, study site, use of vitamin D and calcium supplements, and use of bone-detrimental or -beneficial medications, each SD decrement in lumbar spine (LS) BMD before MT was associated with a 78% increment in fracture hazard (P = .007). Each 1% per year faster decline in LS BMD was related to a 56% greater fracture hazard (P = .04). Rate of LS BMD decline predicted future fracture, independent of starting BMD. Women with a starting LS BMD below the sample median, and an LS BMD decline rate faster than the sample median had a 2.7-fold greater fracture hazard (P = .03). At the femoral neck, neither starting BMD nor rate of BMD decline was associated with fracture.

Conclusion

At the LS, starting BMD before the MT and rate of decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause are independent risk factors for fracture. Women with a below-median starting LS BMD and a faster-than-median LS BMD decline have the greatest fracture risk.

Keywords: menopause, bone mineral density, fracture, general population studies

Bone mineral density (BMD) decreases rapidly during the menopause transition (MT), and continues to decline in postmenopause (1-5). Using a time relative to the final menstrual period (FMP) construct, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) demonstrated that BMD loss accelerates sharply 1 year before the FMP (1). From 1 year before through 2 years after the FMP (referred to herein as the MT), BMD decreases at its greatest rate (2.5% per year at the lumbar spine [LS] and 1.8% per year at the femoral neck [FN]) (1). Approximately 2 years after the FMP, bone loss decelerates, but persists at a lower rate (1.1% at both the LS and FN) (1). For this study, we refer to the interval beginning 2 years after, and ending 5 years after the FMP as early postmenopause. During the 6-year period spanning the MT and early postmenopause, cumulative BMD loss averages approximately 10% at the LS and approximately 8% at the FN (1).

Given the large cumulative decline in BMD during the MT and early postmenopause, and the deterioration in bone microarchitecture (6, 7), quality (8), and strength (9) that accompany this loss, some investigators have proposed that the MT and early postmenopause may be opportune times for early intervention to prevent osteoporosis and fractures (10, 11). Although some studies have reported an association between faster bone loss in older adults with fracture (12-17), the thesis that we should intervene in midlife has not gained universal acceptance, in part, because bone loss during the MT and early postmenopause has not been directly related to subsequent fractures. When BMD decline accelerates at the start of the MT, women are still close to their peak BMD (1). Even after the BMD loss of the MT and early postmenopause, BMD remains above levels that would warrant pharmacologic treatment (18-20). However, if faster BMD decline during the MT and early postmenopause were an independent risk factor for fracture, regardless of starting BMD, the implications would be substantial: Further research to determine whether early, short-term antiresorptive therapy preserves BMD, prevents permanent damage to bone quality, and reduces fracture would be warranted.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to examine whether the rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause predicts incident fracture, independent of starting BMD (before the MT). We addressed 3 specific questions: 1) Is starting BMD, that is, that measured prior to the MT, associated with fracture? 2) Is the rate of BMD loss during the combined MT and early postmenopause associated with fracture? and 3) Do starting BMD and rate of BMD decline predict fracture, independent of the other? Our secondary objective was to explore whether the relation between rate of BMD loss and fracture is different depending on starting BMD. This study was conducted in SWAN, a longitudinal study of the menopause and midlife in a multiracial/ethnic cohort of ambulatory women (21).

Materials and Methods

SWAN is a multicenter, longitudinal study of 3302 community-dwelling, multiracial/ethnic women (21). At study inception, participants were age 42 to 52 years, and in premenopause (no change from usual menstrual bleeding) or early perimenopause (less predictable menstrual bleeding at least once every 3 months). Potential participants were excluded if they did not have an intact uterus and at least one ovary, or were using sex steroid hormones. Seven clinical sites recruited study participants: Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Los Angeles, California; Newark, New Jersey; and Oakland, California. The SWAN Bone Cohort was composed of a subset of 2407 women from 5 sites (excludes Chicago and Newark, where bone assessments were not performed). Since study inception in 1996, 1 baseline visit and 15 follow-up visits have occurred at approximately 18-month intervals. Seventeen percent of Bone Cohort participants dropped out of the study before the end of early postmenopause (the end of the BMD decline exposure period in this study). Participants provided written informed consent, and each site obtained institutional review board approval.

Study Sample Derivation

To examine whether rate of BMD decline during the MT and early postmenopause is associated with subsequent fracture, we required that participants have a known FMP date and 2 BMD measurements: 1 before the start of the MT (1 year prior to the FMP) and 1 soon after the end of early postmenopause (≥ 5, but < 7 years after the FMP). To permit observation of incident fracture after the bone loss exposure period, participants needed to have at least one subsequent SWAN follow-up visit.

From the SWAN Bone Cohort (2407 participants), we excluded women who 1) did not undergo a natural menopause and did not have a discernable FMP date (N = 1256); 2) did not have the 2 required BMD assessments described earlier (N = 448); 3) did not have follow-up after the second BMD assessment during which incident fracture could be ascertained (N = 37); 4) sustained a fracture before the end of early postmenopause (N = 103); and 5) started a bone-beneficial medication that reduces fracture risk (hormone therapy, calcitonin, calcitriol, bisphosphonates, denosumab, or parathyroid hormone) before the end of the bone loss exposure period (N = 112). This left us with an analysis sample of 451 women.

We adjusted for exposure to bone detrimental medications (oral or injectable glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, antiepileptic medications, or chemotherapy), rather than excluding women who used them, for 2 reasons. First, very few women who took these medications used them consistently over the bone loss exposure period. Specifically, 86 of the 451 participants reported taking a bone-detrimental medication at least once during the exposure period (MT and early postmenopause), but only 27 used medication at 2 or more study visits during this period. The median number of visits during the exposure period was 7. Second, the rate of BMD decline during the exposure period and proportion of women who sustained an incident fracture was not significantly different between those who took a bone-detrimental medication compared to those who did not.

Outcome

The primary outcome of analyses was time to first fracture after the conclusion of the bone loss exposure period. At each SWAN follow-up visit, fractures since the previous encounter were self-reported using standardized questionnaires. These questionnaires ascertained the number of fractures, fracture site, and degree of trauma. Fractures were classified as atraumatic if they did not occur after a fall from a height of greater than 6 inches (15 cm), a motor vehicle accident, moving fast (eg, skating), playing sports, or from impact with heavy or fast-moving projectiles. SWAN began recording fracture dates at follow-up visit 7; before this, we imputed fracture dates using the midpoint between the index and previous visits. Also, at follow-up visit 7, SWAN began to confirm fracture occurrence through review of the medical record. Since the inauguration of fracture adjudication, 95% of self-reported events were confirmed. For this analysis, we excluded craniofacial and digital fractures. However, we did include atraumatic and traumatic fractures given the increasing recognition that both fracture types are linked to similarly reduced BMD (22-24).

Primary Exposures

Primary exposures were the starting BMD before the MT and the rate of BMD decline during the bone loss exposure period (combined MT and early postmenopause). At each study visit, LS and FN BMD (g/cm2) were measured using Hologic instruments. An anthropomorphic spine phantom was circulated to create a cross‐site calibration. The Boston, Detroit, and Los Angeles sites began SWAN with Hologic 4500A models and subsequently upgraded to Hologic Discovery A instruments. Davis and Pittsburgh started SWAN with Hologic 2000 models and later upgraded to Hologic 4500A machines. When a site upgraded hardware, it scanned 40 women on its old and new machines to develop cross-calibration regression equations. A standard quality control program included daily phantom measurements, local site review of all scans, central review of scans that met problem-flagging criteria, and central review of a 5% random sample of scans. Short-term in vivo measurement variability was 0.014 g/cm2 (1.4%) for the LS and 0.016 g/cm2 (2.2%) for the FN.

Covariates

Factors that could affect fracture risk, which were also recorded in SWAN, were included as covariates in the analyses. These include age (years), body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms/height in meters2), race/ethnicity, use of calcium supplements, vitamin D supplements, “bone-detrimental medications” (oral or injectable glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, or antiepileptic medications), or “bone-beneficial medications” (hormone therapy, calcitonin, calcitriol, bisphosphonates, denosumab, or parathyroid hormone).

Data Analysis

We operationalized the MT as the interval beginning 1 year before and ending 2 years after the FMP (when BMD decreases most rapidly), and early postmenopause as the 3 years after that. Bone loss exposure started at T1 (1 year before the FMP), and ended at T2 (5 years after the FMP) (Fig. 1). We calculated the rate of BMD decline during this exposure period as the percentage of BMD lost from T0 (the last visit before T1) to T3 (the first visit after the end of early postmenopause), divided by the number of years from T1 to T3 (Fig. 1). We used the BMD assessment at T0 as our starting BMD. We believe this BMD measurement is close to peak bone mass because areal BMD does not decrease significantly prior to this time point in SWAN (1). The Spearman rank correlation between rate of BMD decline during the MT and rate of BMD loss during the combined MT and early postmenopause was greater than 0.7.

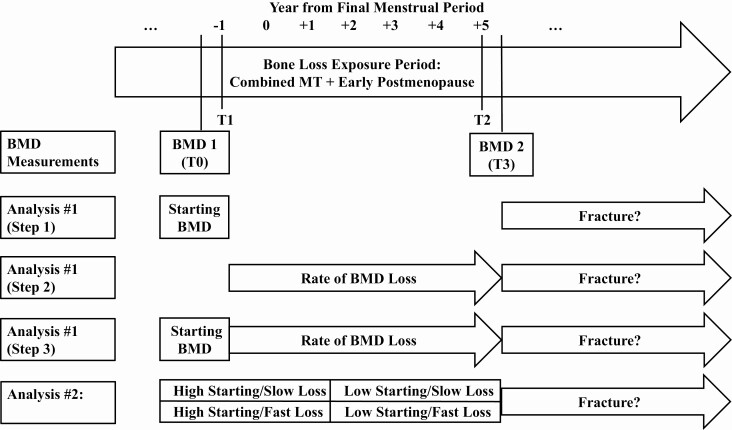

Figure 1.

The menopause transition (MT) was defined as 1 year before to 2 years after the final menstrual period (FMP), and early postmenopause as the 3 years after that. The starting bone mineral density (BMD) measurement was obtained from the last study visit before T1 (T0). The exposure period over which bone loss was calculated was the combined MT and early postmenopause, spanning 1 year before (T1) to 5 years (T2) after the FMP. Specifically, rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause was computed as the percentage of BMD that was lost T0 to the first visit after T2 (T3), divided by the number of years from T1 to T3. BMD did not decrease significantly in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation before T1. The BMD measurement at T0 is thus a close approximation of peak areal BMD. In the first set of analyses, we used 3 steps to test whether rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause predicts incident fracture independent of starting BMD before the MT. Steps 1 and 2 separately examined starting BMD and rate of BMD decline, respectively, as predictors of fracture. Step 3 included both starting BMD and rate of BMD loss in the same model. In the second set of analyses, we examined whether the rate of BMD decline and starting BMD have a synergistic effect on fracture.

To examine whether the rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause predicts incident fractures after early postmenopause, independent of starting BMD, we used a 3-step approach: Step 1 tested whether starting BMD is associated with fracture, step 2 tested whether rate of BMD loss is related to fracture, and step 3 tested whether starting BMD and rate of BMD decline predict fracture independent of the other. In all steps, we used Cox proportional hazards regression, which investigates how variables of interest relate to time to event (25) (in this case, how starting BMD and/or rate of BMD decline relate to time to first fracture).

In step 1, we used Cox proportional hazards regression with time to first fracture after the end of early postmenopause (clock starting at T3) as the outcome, and starting LS or FN BMD (measured at T0, the last visit before the start of the MT) as primary predictors in separate models. Covariates included in this and subsequent steps were age, BMI, race/ethnicity, SWAN study site, exposure to vitamin D, calcium, or bone-detrimental medications before T3, and exposure to vitamin D, calcium, bone-detrimental, or bone-beneficial medications after T3. Values of age and BMI were those obtained at T3. Exposure to vitamin D, calcium, and bone-detrimental medications before T3 was estimated as the percentage of visits before T3 at which participants reported use. Similarly, we calculated exposure to vitamin D, calcium, bone-detrimental, and bone-beneficial medications after T3 as the percentage of visits after T3 at which participants reported use. For each time period (before T3 or after T3), separate variables were created for each supplement or medication category. In step 2, we again used Cox proportional hazards regression with time to first fracture after T3 as the outcome, but used rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause. Rates of BMD loss at the LS and FN were tested separately. Covariates were handled as in step 1. In step 3, we confirmed that the starting BMD and the rate of BMD decline were not collinear, and then modeled both as predictors of time to first fracture after T3 in the same Cox proportional hazards model.

Our secondary objective was to explore whether starting BMD before the MT and rate of BMD decline during the MT and early postmenopause had synergistic effects on incident fracture. We classified starting BMD as high or low depending on whether the value was greater or less than the site-specific (LS or FN) sample median, and rate of BMD decline as fast or slow based on whether the site-specific rate was above or below the median rate. For the LS or FN (each tested separately), we tested membership in 4 groups (high starting BMD and slow BMD decline; high starting BMD and fast BMD decline; low starting BMD and slow BMD decline; low starting BMD and fast BMD decline) as a predictor of time to fracture after T3 using Cox proportional hazard regression. Covariates were the same as those described for the primary outcome models.

We conducted 2 sets of sensitivity analyses. To determine whether including participants who took a bone-detrimental medication during the combined MT and early postmenopause influenced our findings, we reran all models, excluding the 86 women who used bone-detrimental medications before T3 (the start of fracture follow-up). To determine whether including traumatic fractures as outcomes influenced our results, we reran all models, but excluded traumatic fractures.

All analyses were performed using STATA 15.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The analytic sample included 451 women: 31% were Black, 13% Chinese, 16% Japanese, and 40% White. On average, at the time of the starting BMD measurement before the MT, participants were aged 49 years, 1.7 years before their FMP, and had a BMI of 28.3. Mean starting LS BMD was 1.075 g/cm2 with an SD of 0.142 g/cm2. Mean (SD) starting BMD at the FN was 0.848 (0.128) g/cm2. At the time of the first visit after early postmenopause, mean (SD) BMD was 0.966 (0.153) g/cm2 at the LS, and 0.767 (0.124) g/cm2 at the FN. The average number of years elapsed between the first and second BMD measurements was 6.7 years. Rates of BMD decline over the combined MT and early postmenopause were normally distributed, with mean (SD) values of 1.5 (1.0) and 1.3 (0.9)% per year at the LS and FN, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of analytic sample: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN)a

| Characteristics at specified observation times | Mean (SD) or count (%) |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 139 (31) |

| Chinese | 57 (13) |

| Japanese | 72 (16) |

| White | 183 (40) |

| Values at last visit prior to onset of menopause transition b | |

| Age, y | 49.7 (2.3) |

| Time before final menstrual period, y | 1.7 (0.9) |

| Body mass index | 28.3 (6.9) |

| Lumbar spine bone mineral density, g/cm2 | 1.075 (0.142) |

| Femoral neck bone mineral density, g/cm2 | 0.848 (0.128) |

| Values at first visit after end of early postmenopause c | |

| Age, y | 57.1 (1.3) |

| Time after final menstrual period, y | 5.7 (0.5) |

| Lumbar spine bone mineral density, g/cm2 | 0.966 (0.153) |

| Femoral neck bone mineral density, g/cm2 | 0.767 (0.124) |

| Rate of bone mineral density decline during combined menopause transition and early postmenopause d | |

| Lumbar spine bone mineral density, % per y | 1.5 (1.0) |

| Femoral neck bone mineral density, % per y | 1.3 (0.9) |

| Medication or supplement use before end of early postmenopause | |

| Ever use | |

| Bone-detrimental medicationse | 86 (19) |

| Vitamin D supplement | 256 (57) |

| Calcium supplement | 274 (61) |

| Percentage of visits reporting use among “ever users” | |

| Bone-detrimental medicationse | 18 (11) |

| Vitamin D supplement | 53 (30) |

| Calcium supplement | 59 (31) |

| Medication or supplement use after end of early postmenopause | |

| Ever use | |

| Bone-detrimental medicationse | 66 (14) |

| Bone-beneficial medicationsf | 73 (16) |

| Vitamin D supplement | 256 (57) |

| Calcium supplement | 275 (61) |

| Percentage of visits reporting use among “ever users” | |

| Bone-detrimental medicationse | 44 (45) |

| Bone-beneficial medicationsf | 40 (29) |

| Vitamin D supplements | 58 (25) |

| Calcium supplement | 57 (25) |

a N = 451; values in table are counts (percentage) for categorical variables; means (SD) for continuous variables.

b The start of the menopause transition (MT) operationalized as 1 year before the final menstrual period (when bone mineral density [BMD] decline accelerates) (1). We consider BMD measured at this time point to be an approximation of peak BMD in SWAN because there is not significant bone loss before the start of the MT. The bone loss exposure period for this study begins with the MT and finishes at the end of early postmenopause.

c The end of early postmenopause operationalized as 5 years after the final menstrual period, defining the end of the bone loss exposure period for this study. The first visit after early postmenopause marks the onset of the fracture observation period.

d Rate of BMD decline calculated over the exposure period spanning the MT and early postmenopause (operationalized as beginning 1 year before, and ending 5 years after the final menstrual period).

e Bone-detrimental medications include any of the following: oral or injectable glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, or antiepileptic medications.

f Bone-beneficial medications include any of the following: hormone therapy, calcitonin, calcitriol, bisphosphonates, denosumab, or parathyroid hormone.

Mean (SD) time to first fracture or censoring was 6.8 (3.1) years. A total of 34 (8%) women sustained an incident fracture after early postmenopause. Fractures occurred (in order of decreasing frequency) at the wrist, ankle, foot, leg (above the ankle), arm (above the wrist), ribs, spine, hip, and shoulder. Twelve of the 34 (35%) fractures were considered traumatic. The racial/ethnic breakdown of fracture events were as follows: 31% Black, 13% Chinese, 5% Japanese, and 51% White.

Starting Bone Mineral Density (BMD) and Rate of BMD Decline as Independent Predictors of Fracture

In Cox proportional hazards regression, lower LS BMD before the MT and faster LS BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause were associated with greater rates of future fracture (when tested as individual predictors, or in the same model) before and after adjustment for covariates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of starting bone mineral density (BMD) measured before menopause transition (MT)a and rate of BMD decline during combined MT and early postmenopauseb with incident fracture

| Hazard ratio per SD decrement in starting BMD or 1% per y faster decline in BMD (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI)c | P | Adjusted HR (95% CI)d | P | |

| Step 1: Starting BMD, g/cm 2 | ||||

| Lumbar spine | 2.02 (1.27-3.19) | .003 | 1.78 (1.17-2.72) | .007 |

| Femoral neck | 1.18 (0.84-1.66) | .3 | 1.24 (0.79-1.96) | .3 |

| Step 2: Rate of BMD decline during MT and early postmenopause, % per y | ||||

| Lumbar spine | 1.51 (1.03-2.20) | .03 | 1.56 (1.02-2.41) | .04 |

| Femoral neck | 1.26 (0.86-1.86) | .2 | 1.31 (0.87-1.96) | .1 |

| Step 3: Starting BMD, g/cm 2 , and rate of BMD decline, % per y | ||||

| Lumbar spine | ||||

| Starting BMD | 2.06 (1.29-3.29) | .003 | 1.85 (1.19-2.83) | .005 |

| Rate of BMD decline | 1.45 (1.01-2.09) | .04 | 1.49 (1.01-2.20) | .04 |

| Femoral neck | ||||

| Starting BMD | 1.33 (0.90-1.99) | .1 | 1.39 (0.88-2.42) | .1 |

| Rate of BMD decline | 1.35 (0.90-2.01) | .1 | 1.46 (0.94-2.26) | .09 |

a Starting BMD using the last BMD measurement before the start of MT.

b Rate of BMD decline calculated over the exposure period spanning MT and early postmenopause (operationalized as beginning 1 year before, and ending 5 years after the final menstrual period).

c Cox proportional hazards regression with time to first fracture after early postmenopause as outcome, starting BMD before the MT (step 1), rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause (step 2), or both (step 3) as predictors. Separate models were conducted for lumbar spine and femoral neck exposures.

d Cox proportional hazards regression as described in note “c,” but with full adjustment for age, body mass index, race/ethnicity, study site, and exposure to vitamin D, calcium, bone-detrimental medications, and bone-beneficial medications.

After accounting for age, BMI, race/ethnicity, study site, and exposure to vitamin D, calcium, bone-negative medications, and bone-positive medications, each SD decrement in starting LS BMD was related to a 78% (P = .007) greater hazard for incident fracture. Starting BMD at the FN was not associated with incident fracture hazard in unadjusted or adjusted models (see Table 2).

Adjusted for the same covariates, using Cox proportional hazards regression, rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause at the LS predicted incident fracture (see Table 2). For each 1% per year faster loss of LS BMD, fracture hazard was 56% (P = .04) greater. At the FN, there was a trend toward faster BMD decline being associated with fracture, but this did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio [HR] per each 1% per year faster BMD decrease = 1.32, P = .1).

When included in the same model, and adjusted for the same aforementioned covariates, both starting BMD and rate of BMD decline at the LS predicted future fracture independent of the other (see Table 2). Accounting for starting BMD before the MT, each 1% per year faster BMD loss during the combined MT and early postmenopause was related to a 49% greater fracture hazard (P = .04). Conversely, after accounting for rate of BMD decline, each SD decrement in starting BMD was associated with an 85% greater (P = .005) fracture hazard. At the FN, there was a trend that faster BMD decline was associated with subsequent fracture when accounting for starting FN BMD, but this was not statistically significant (HR per 1% per year faster BMD loss = 1.46, P = .09) (see Table 2).

Synergistic Effects of Starting Bone Mineral Density (BMD) and Rate of BMD Decline on Fracture

At the LS, 137 of the 451 women in the analysis sample had both high starting BMD (≥ 1.064 g/cm2) and slow bone loss (≤ 1.5% per year); they served as the reference group. The 3 comparator groups consisted of 91 participants in the high starting BMD/fast BMD decline group, 92 women in the low starting BMD/slow BMD decline group, and 131 participants in the starting BMD/fast BMD decline group. At the FN, the breakdown was 111 high starting BMD (≥ 0.828 g/cm2)/slow BMD decline (≤ 1.3% per year) (reference group), 115 high starting BMD/fast BMD decline, 116 low starting BMD/slow BMD decline, and 109 low starting BMD/fast BMD decline.

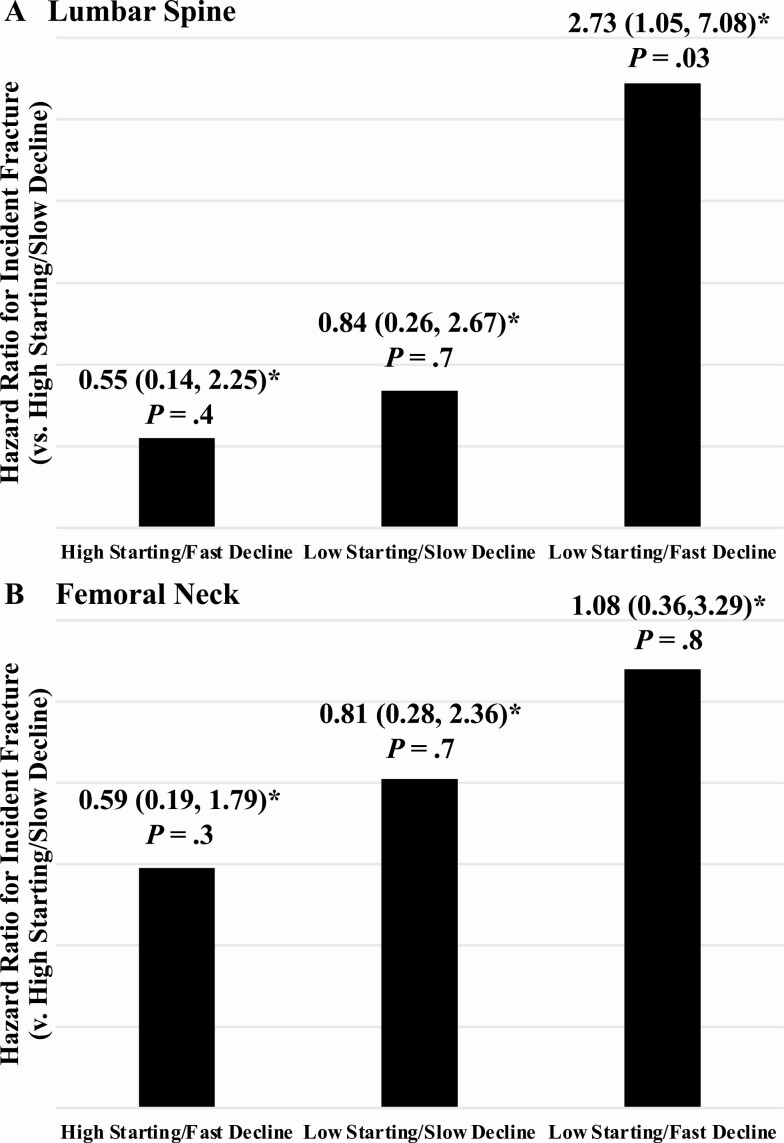

In Cox proportional hazards regression, before adjusting for covariates, women with low starting BMD and fast BMD decline at the LS had a 2.56-fold greater fracture hazard (P = .04) than women in the reference group. Accounting for the same covariates mentioned earlier did not substantially change these results (HR = 2.73, P = .03). Starting BMD and BMD decline at the FN did not have a synergistic effect on fracture in unadjusted or adjusted models (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Synergistic effects of starting bone mineral density (BMD) before the menopause transition (MT) and rate of BMD decline during combined the MT and early postmenopause on fracture. At both the lumbar spine and femoral neck, participants were categorized as having high vs low starting BMD (greater or less than site-specific sample median) and slow vs fast BMD decline (decline slower or faster than site-specific median rate). For the lumbar spine and femoral neck (each tested separately), we tested membership in 4 groups (high starting BMD and slow BMD decline [reference]; high starting BMD and fast BMD decline; low starting BMD and slow BMD decline; low starting BMD and fast BMD decline) as a predictor of time to fracture after early postmenopause using Cox proportional hazard regression. Covariates included age, body mass index, race/ethnicity, study site, and exposure to vitamin D, calcium, bone-detrimental medications, and bone-beneficial medications. *Hazard ratios compared to reference group (high starting BMD and slow BMD decline).

Sensitivity Analyses

Among the 86 women who used a bone detrimental medication before the end of early postmenopause, 7 (8%) sustained an incident fracture. Excluding these women did not change our results (data not shown). When traumatic fractures were excluded as outcome events, the relation between starting LS BMD and fracture remained unchanged (data not shown). The associations of rate of BMD decline at the LS with fracture were no longer significant, but the effect sizes were similar to those in the primary analyses (HR = 1.54, P = .1 when tested individually or with starting BMD).

Discussion

This study examined whether the rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause is associated with incident fractures, independent of BMD before the MT. We report that, at the LS, faster BMD decline during midlife is a risk factor for subsequent fracture, independent of starting BMD. Moreover, women with low starting BMD and fast BMD decline at the LS have the greatest risk of fracture. Numerous studies have investigated whether faster BMD loss contributes to fracture in older adults who have already lost substantial BMD (12-17, 26-28). To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to link faster BMD loss during the MT and early postmenopause, when women are in their 40s and 50s and near their peak BMD, to future fracture.

Our finding that faster LS BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause is an independent risk factor for fracture supports the thesis that a woman’s midlife is a previously underappreciated period when fracture risk accelerates (8, 11, 29). Until recently, this concept was based, in part, on the assumption that rapid bone loss reflects high bone turnover (6, 30-33), which leads to alterations in bone microarchitecture that are associated with reduced bone strength (eg, decreased trabecular number, increased trabecular spacing, conversion of trabecular plates to rods, decreased trabecular connectivity, trabecular perforation) (7, 34, 35). Along these lines, SWAN has demonstrated that rapid loss of BMD during the MT and early postmenopause is accompanied by decreased trabecular bone quality and femoral neck strength (1, 8). This study provides direct evidence that faster bone loss during the MT and early postmenopause relates to fracture, despite BMD values not reaching levels that would qualify for pharmacologic treatment under current practice paradigms (18-20).

The long-term, clinical implication of our results is that the MT and early postmenopause may be time-limited opportunities for short-term antiresorptive therapy to lessen a woman’s risk of future fracture (10, 11). Although clinical trials to test the efficacy of this approach are still multiple research steps away, potential strategies are worth considering. One possibility is to administer 1 or 2 doses of zoledronic acid during the 6-year period spanning the MT and early postmenopause. Zoledronic acid is a potent antiresorptive, and 1 dose can maintain BMD for 3 to 5 years (36-38). Preserving bone that would otherwise be lost during the MT and early postmenopause could disproportionately benefit future bone health. In our analysis, total BMD loss during this period averaged 10.6% at the LS and 9.1% at the FN. For reference, even optimized sequences of teriparatide and denosumab or romosozumab and denosumab increase FN BMD by only 8.3% (39) or 6.6% (40), respectively. Our finding that women with both low starting BMD and fast BMD decline had the greatest rate of fracture suggests that future studies should also examine whether the potential benefits of early intervention are different depending on starting BMD.

While numerous studies have tested whether faster bone loss predicts future fractures, results are inconsistent (12-17, 26-28). This may be because BMD changes slowly relative to the precision of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)-based BMD measurements (18, 19, 41). For the bone loss “signal” to be captured, the rate of BMD decline needs to be high and/or the interval between DXA scans must be sufficiently long. In this study, mean total BMD loss during the combined MT and early postmenopause was greater than the site-specific least significant change (LSC), but more so at the LS than at the FN. On average, total decline at the LS was 10.6%, about 2.5 times larger than the LSC for that site (3.9%). At the FN, the total decline of 9.1% was 1.5 times greater than the FN LSC (6.2%). This relatively lower signal at the FN may be one reason that rate of BMD loss at the FN did not predict fracture. It is even more difficult to relate bone loss to fracture in older adults because BMD decline can be up to 300% slower: For example, BMD loss at the FN averaged 0.4% per year in a sample of older individuals in the Manitoba cohort vs 1.3% per year in our study (1, 28). In studies of older postmenopausal women and men, bone loss was associated with fracture only if the sample size was large (12, 13), BMD was measured over extended follow-up (14, 15), or BMD was ascertained at sites with small variability (14, 16, 17).

In SWAN, our starting BMD measurement taken before the MT is a reasonable approximation of peak areal BMD because significant bone loss does not occur prior to the MT in the cohort (1). This is noteworthy because although peak BMD has long been considered a determinant of fracture (42), this study is one of the first direct assessments of this assumption. Previously, this concept was inferred from individual findings: 1) bone is accrued from conception to young adulthood (43); 2) bone loss predominates in later adulthood (1, 13, 44); 3) the population distribution of BMD does not widen with age (45); and 4) a person’s position in this distribution remains constant over time (46). SWAN’s study design permits the direct testing of an approximation of peak BMD as a predictor for fracture because participants were in premenopause (before significant bone loss had occurred) at study inception. In this study, the gradient of risk between LS BMD before the MT and fracture was similar to that in another SWAN publication (47). At the FN, we did not detect an association between BMD before the MT and fracture, but a prior SWAN analysis with a larger sample size (N = 1940) reported that each SD decrement in FN BMD was associated with a 61% greater (P = .01) risk of fracture (48). Heritability accounts for 50% to 80% of variation in peak BMD (49, 50); data from SWAN suggest that optimizing lifestyle factors to maximize peak BMD during childhood and adolescence (eg, calcium intake [51-53], physical activity [50, 52]) may benefit bone health in later life.

Several limitations warrant mention. First, although the rate of BMD decline during the MT is faster than in early postmenopause, our approach to calculating the rate of BMD loss during the combined MT and early postmenopause assumes that the rate of decline is constant. We used this extended exposure period to maximize our BMD loss “signal.” Despite the change in BMD decline rate from the MT to early postmenopause, the rate of BMD loss during the MT is highly correlated to rate of BMD decline during the combined MT and early postmenopause (Spearman rank correlation > 0.7). Second, because the number of fracture events was relatively small, we included both atraumatic and traumatic fractures in one composite outcome. We justify this approach based on the growing recognition that both fracture types are associated with similarly reduced BMD (22, 23). Although the association between rate of LS BMD decline with subsequent fracture was no longer statistically significant in sensitivity analyses that excluded traumatic events, the effect size did not change. This suggests that including traumatic fractures in the primary analyses to increase power did not bias our findings. Second, although spine and hip fracture lead to the greatest morbidity and mortality (54), most fractures in this younger cohort occurred at distal appendicular sites. We propose that identifying risk factors for these fractures is relevant because distal appendicular fractures foreshadow spine and hip fracture in later life (55-57). Third, we did not have sufficient fractures in individual racial/ethnic groups to examine whether there were race/ethnicity-based differences in the relation between BMD decline and fracture. However, the racial/ethnic distribution of participants who sustained a fracture in our sample was similar to that of those who did not; we therefore would not expect race/ethnicity to modify the association of BMD decline with fracture.

To summarize, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to demonstrate that faster BMD decline at the LS during the combined MT and early postmenopause is a risk factor for subsequent fracture, independent of starting BMD before the MT. We also showed that women with both low starting BMD and fast BMD decline at the LS have the greatest risk of future fracture. To better understand the clinical implications of these findings, further research must 1) ascertain whether it is possible to identify women who are likely to lose BMD at the greatest rate during the MT and early postmenopause (before substantial bone loss occurs); 2) determine whether early, short-term antiresorptive therapy during the MT and early postmenopause preserves BMD, prevents permanent damage to bone microarchitecture, and mitigates the risk of future fracture; and 3) explore whether the potential benefits of early intervention are different depending on BMD measured before the MT.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: SWAN has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (grant Nos. NR004061; AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, and AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH, or the NIH.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BMI

body mass index

- FMP

final menstrual period

- FN

femoral neck

- HR

hazard ratio

- LS

lumbar spine

- LSC

least significant change

- MT

menopause transition

- SWAN

Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References (21). The analyzed data are publicly available and can be accessed at https://www.swanstudy.org/.

References

- 1. Greendale GA, Sowers M, Han W, et al. Bone mineral density loss in relation to the final menstrual period in a multiethnic cohort: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(1):111-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berger C, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, et al. ; Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group . Change in bone mineral density as a function of age in women and men and association with the use of antiresorptive agents. CMAJ. 2008;178(13):1660-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burger H, van Daele PL, Algra D, et al. The association between age and bone mineral density in men and women aged 55 years and over: the Rotterdam Study. Bone Miner. 1994;25(1):1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ravn P, Hetland ML, Overgaard K, Christiansen C. Premenopausal and postmenopausal changes in bone mineral density of the proximal femur measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9(12):1975-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warming L, Hassager C, Christiansen C. Changes in bone mineral density with age in men and women: a longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13(2):105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Recker R, Lappe J, Davies KM, Heaney R. Bone remodeling increases substantially in the years after menopause and remains increased in older osteoporosis patients. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(10):1628-1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Akhter MP, Lappe JM, Davies KM, Recker RR. Transmenopausal changes in the trabecular bone structure. Bone. 2007;41(1):111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greendale GA, Huang M, Cauley JA, et al. Trabecular bone score declines during the menopause transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(4):e1872-e1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishii S, Cauley JA, Greendale GA, et al. Trajectories of femoral neck strength in relation to the final menstrual period in a multi-ethnic cohort. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(9):2471-2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zaidi M, Turner CH, Canalis E, et al. Bone loss or lost bone: rationale and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of early postmenopausal bone loss. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;7(4):118-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karlamangla AS, Burnett-Bowie SM, Crandall CJ. Bone health during the menopause transition and beyond. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(4):695-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berger C, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, et al. ; CaMos Research Group . Association between change in BMD and fragility fracture in women and men. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(2):361-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cawthon PM, Ewing SK, McCulloch CE, et al. ; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Research Group . Loss of hip BMD in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(10):1728-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Riis BJ, Hansen MA, Jensen AM, Overgaard K, Christiansen C. Low bone mass and fast rate of bone loss at menopause: equal risk factors for future fracture: a 15-year follow-up study. Bone. 1996;19(1):9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen TV, Center JR, Eisman JA. Femoral neck bone loss predicts fracture risk independent of baseline BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(7):1195-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmed LA, Emaus N, Berntsen GK, et al. Bone loss and the risk of non-vertebral fractures in women and men: the Tromsø Study. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(9):1503-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD. Rate of forearm bone loss is associated with an increased risk of fracture independently of bone mass in postmenopausal women: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(11):1929-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—2020 update executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(5):564-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eastell R, Rosen CJ. Response to letter to the editor: “Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline”. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(8):3537-3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians . Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(11):818-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. SWAN: a multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo R, Kelsey J, Marcus R, eds. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press; 2000:175-188. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cummings SR, Eastell R. Stop (mis)classifying fractures as high- or low-trauma or as fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(6):1023-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leslie WD, Schousboe JT, Morin SN, et al. Fracture risk following high-trauma versus low-trauma fracture: a registry-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(6):1059-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Warriner AH, Patkar NM, Curtis JR, et al. Which fractures are most attributable to osteoporosis? J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):46-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fisher LD, Lin DY. Time-dependent covariates in the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berry SD, Samelson EJ, Pencina MJ, et al. Repeat bone mineral density screening and prediction of hip and major osteoporotic fracture. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1256-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, et al. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leslie W, Morin S, Lix L. Rate of bone density change does not enhance fracture prediction in routine clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):1211-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shieh A, Greendale GA, Cauley JA, Karlamangla AS. The association between fast increase in bone turnover during the menopause transition and subsequent fracture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(4):e1440-e1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shieh A, Ishii S, Greendale GA, Cauley JA, Lo JC, Karlamangla AS. Urinary N-telopeptide and rate of bone loss over the menopause transition and early postmenopause. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(11):2057-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gossiel F, Altaher H, Reid DM, et al. Bone turnover markers after the menopause: T-score approach. Bone. 2018;111:44-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rogers A, Hannon RA, Eastell R. Biochemical markers as predictors of rates of bone loss after menopause. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(7):1398-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ebeling PR, Atley LM, Guthrie JR, et al. Bone turnover markers and bone density across the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(9):3366-3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang J, Stein EM, Zhou B, et al. Deterioration of trabecular plate-rod and cortical microarchitecture and reduced bone stiffness at distal radius and tibia in postmenopausal women with vertebral fractures. Bone. 2016;88:39-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shanbhogue VV, Brixen K, Hansen S. Age- and sex-related changes in bone microarchitecture and estimated strength: a three-year prospective study using HRpQCT. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(8):1541-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2407-2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reid IR, Black DM, Eastell R, et al. ; HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial and HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial Steering Committees . Reduction in the risk of clinical fractures after a single dose of zoledronic acid 5 milligrams. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(2):557-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grey A, Horne A, Gamble G, Mihov B, Reid IR, Bolland M. Ten years of very infrequent zoledronate therapy in older women: an open-label extension of a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(4):e1641-e1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leder BZ, Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, et al. Denosumab and teriparatide transitions in postmenopausal osteoporosis (the DATA-Switch study): extension of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1147-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1532-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2019 ISCD official positions—adult 2019. August 1, 2019. Accessed November 1, 2020. https://iscd.org/learn/official-positions/adult-positions/

- 42. Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(12):985-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferrari S, Rizzoli R, Slosman D, Bonjour JP. Familial resemblance for bone mineral mass is expressed before puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(2):358-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, et al. ; Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group . BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(11):1947-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Newton-John HF, Morgan DB. The loss of bone with age, osteoporosis, and fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;71:229-252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matković V, Kostial K, Simonović I, Buzina R, Brodarec A, Nordin BE. Bone status and fracture rates in two regions of Yugoslavia. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32(3):540-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Greendale GA, et al. Bone resorption and fracture across the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2012;19(11):1200-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ishii S, Greendale GA, Cauley JA, et al. Fracture risk assessment without race/ethnicity information. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(10):3593-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Christian JC, Yu PL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC Jr. Heritability of bone mass: a longitudinal study in aging male twins. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44(3):429-433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McGuigan FE, Murray L, Gallagher A, et al. Genetic and environmental determinants of peak bone mass in young men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(7):1273-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matkovic V, Fontana D, Tominac C, Goel P, Chesnut CH III. Factors that influence peak bone mass formation: a study of calcium balance and the inheritance of bone mass in adolescent females. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52(5):878-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Välimäki MJ, Kärkkäinen M, Lamberg-Allardt C, et al. Exercise, smoking, and calcium intake during adolescence and early adulthood as determinants of peak bone mass. Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study Group. BMJ. 1994;309(6949):230-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matkovic V. Calcium metabolism and calcium requirements during skeletal modeling and consolidation of bone mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(1 Suppl):245S-260S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Forsén L, Sogaard AJ, Meyer HE, Edna T, Kopjar B. Survival after hip fracture: short- and long-term excess mortality according to age and gender. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10(1):73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Karlsson MK, Hasserius R, Obrant KJ. Individuals who sustain nonosteoporotic fractures continue to also sustain fragility fractures. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;53(4):229-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Cauley JA, et al. Wrist fracture and risk of subsequent fracture: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(11):2086-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gehlbach S, Saag KG, Adachi JD, et al. Previous fractures at multiple sites increase the risk for subsequent fractures: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(3):645-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References (21). The analyzed data are publicly available and can be accessed at https://www.swanstudy.org/.