Abstract

Context

Iodide transport defect (ITD) (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man No. 274400) is an uncommon cause of dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism due to loss-of-function variants in the SLC5A5 gene, which encodes the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS), causing deficient iodide accumulation in thyroid follicular cells.

Objective

This work aims to determine the molecular basis of a patient’s ITD clinical phenotype.

Methods

The propositus was diagnosed with dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism with minimal 99mTc-pertechnetate accumulation in a eutopic thyroid gland. The propositus SLC5A5 gene was sequenced. Functional in vitro characterization of the novel NIS variant was performed.

Results

Sanger sequencing revealed a novel homozygous missense p.G561E NIS variant. Mechanistically, the G561E substitution reduces iodide uptake, because targeting of G561E NIS to the plasma membrane is reduced. Biochemical analyses revealed that G561E impairs the recognition of an adjacent tryptophan-acidic motif by the kinesin-1 subunit kinesin light chain 2 (KLC2), interfering with NIS maturation beyond the endoplasmic reticulum, and reducing iodide accumulation. Structural bioinformatic analysis suggests that G561E shifts the equilibrium of the unstructured tryptophan-acidic motif toward a more structured conformation unrecognizable to KLC2. Consistently, knockdown of Klc2 causes defective NIS maturation and consequently decreases iodide accumulation in rat thyroid cells. Morpholino knockdown of klc2 reduces thyroid hormone synthesis in zebrafish larvae leading to a hypothyroid state as revealed by expression profiling of key genes related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis.

Conclusion

We report a novel NIS pathogenic variant associated with dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism. Detailed molecular characterization of G561E NIS uncovered the significance of KLC2 in thyroid physiology.

Keywords: dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism, iodide transport defect, sodium/iodide symporter, tryptophan-acidic motif, kinesin light chain 2, impaired transport to the plasma membrane

Congenital hypothyroidism is the most frequent endocrine disorder in neonates. A recent meta-analysis indicates that 31% to 42% of patients with congenital hypothyroidism in iodine-sufficient countries have a eutopic thyroid gland consistent with genetic defects impairing thyroid hormone synthesis, also called dyshormonogenesis (1). In particular, iodide transport defect (ITD) is an uncommon autosomal recessive disorder caused by the inability of thyroid follicular cells to actively accumulate iodide, thus leading to dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism (2, 3). A diagnostic hallmark of this disease is reduced to absent radioiodide accumulation in a thyroid gland in the normal position and a low saliva-to-plasma iodide ratio.

Active iodide accumulation, the first step in the synthesis of the iodine-containing thyroid hormones—which are essential for development and maturation of the central nervous system in the fetus and newborn—is mediated by the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) (4). Human NIS is an integral plasma membrane glycoprotein of 643 amino acids located on the basolateral surface of thyroid follicular cells (5). NIS-mediated iodide transport is electrogenic (2 Na+:1 I– stoichiometry) and couples the inward transport of iodide against its electrochemical gradient to the inward transport of Na+ down its electrochemical gradient (6). Remarkably, NIS transports iodide efficiently at the submicromolar concentrations—orders of magnitude below its KM for iodide—at which it is found in the bloodstream by taking advantage of the physiological Na+ concentration (7).

To date, more than 20 pathogenic variants in the NIS-coding SLC5A5 gene have been identified in patients with thyroid dyshormonogenesis. The detailed molecular analysis of several ITD-causing NIS mutants has yielded key mechanistic information on NIS structure/function relations; remarkably several amino acid residues have been identified as critical for substrate binding, specificity, and stoichiometry, as well as folding and plasma membrane targeting (8-12). These studies have led to the identification of an allosteric site in NIS that, when occupied by the environmental pollutant perchlorate (ClO4–), changes the mechanism by which NIS transports iodide (13).

Here, we report a thorough molecular characterization of the missense pathogenic variant G561E NIS, identified in a pediatric patient with dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism. We show that G561E lowers iodide uptake owing to defective expression of the NIS molecule at the plasma membrane. Bioinformatics and biochemical analyses indicate that G561E impairs the recognition of an adjacent tryptophan-acidic motif [L/M] × W[D/E] by the adapter kinesin light chain 2 (KLC2) of the motor protein kinesin-1, thus reducing NIS export from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and further transport to the plasma membrane. Underscoring the significance of KLC2 in thyroid physiology, in vivo experiments revealed that knocking down KLC2 reduces NIS-mediated iodide accumulation in the thyroid cell line PCCl3 and thyroid hormone synthesis in zebrafish larvae. Taken together, our data suggest that kinesin-1 participates in anterograde ER-to-Golgi transport of newly synthesized NIS molecules in thyroid follicular cells—a significant finding, given that NIS function has been successfully harnessed theranostically using a variety of imaging and therapeutic substrates.

Materials and Methods

Patient

The propositus was a full-term, 3680-g male infant born in 2005 from healthy nonconsanguineous Argentinian parents. On day 2, an abnormally high thyrotropin (TSH) level was detected by newborn screening (64 µIU/ml, cutoff < 10 µIU/mL). The diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism was confirmed on day 10 by determining the following values: TSH 203 µIU/mL (range, 0.9-9.0 µIU/mL), free thyroxine (T4) 1.6 ng/dL (range, 1.2-2.6 ng/dL), total T4 8.7 µg/dL (range, 7.1-19.2 µg/dL), and total 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine 121 ng/dL (range, 111-286 ng/dL). Serum thyroglobulin (Tg) level was slightly increased at 84 ng/mL (range, 6.4-82.8 ng/mL) and thyroid autoantibodies were negative. Age-specific reference intervals were established in-house (14). Thyroid function analyses were performed by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay by Cobas e412 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics). Ultrasonography showed a normal size (thyroid volume 2.8 mL; range, 0.7-3.3 mL) and properly located thyroid gland. Radionuclide scintigraphy revealed diffuse and severely reduced, though not absent, 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake by the thyroid gland, suggesting a defect in iodide accumulation. 99mTc-pertechnetate accumulation in the salivary gland was not tested. Determination of saliva-to-plasma iodide ratios was not technically possible in the Division of Nuclear Medicine.

Thyroid hormone supplementation was started immediately after diagnosis, with a daily dose of 14 µg/kg levothyroxine. Thyroid function was normalized during the first month of levothyroxine replacement therapy. However, the patient may have been noncompliant with his substitutive hormonal treatment, as suggested by several elevated serum TSH values that have been recorded over the course of a 5-year follow-up period. At age 5 years, thyroid function evaluation indicated persistent congenital hypothyroidism (TSH 42.2 µU/mL, free T4 1.4 ng/dL). The parents were clinically and biochemically euthyroid.

Sanger Sequencing

The genetic analysis was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital de Niños de la Santísima Trinidad, Córdoba, Argentina, and performed with the written informed consent of the propositus’ mother. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega). All coding exons and exon-intron boundaries of the SLC5A5 gene were examined by Sanger sequencing (Macrogen) (15).

Expression Vectors and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Amino-terminus hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged human NIS and green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged mouse kinesin light chain 2 (KLC2) expression vectors were the same that have previously been used (11, 16). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with oligonucleotides carrying the desired mutation using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore), which was followed by template plasmid digestion with DpnI (New England BioLabs) (17). The fidelity of all constructs was verified by Sanger sequencing (Macrogen).

Cell Culture, Transfections, and Transductions

Type II Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK-II) and human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Cells were transfected at the ratio of 4 µg plasmid/10-cm dish using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) (18). Stable MDCK-II polyclonal populations were selected and propagated in media containing 1 g/L G418 (AG Scientific).

The Fisher rat–derived thyroid cell lines FRTL-5 and PCCl3 were cultured in DMEM/Ham F-12 medium supplemented with 5% calf bovine serum (Thermo-Fisher Scientific), 1 mIU/mL bovine TSH (National Hormone and Peptide Program), 10 μg/mL bovine insulin, and 5 μg/mL bovine transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich) (19). When cells reached 60% to 70% confluence, they were cultured in the same media for 3 days without TSH but containing 0.2% serum, before treatment with 0.5 mIU/mL TSH for 48 hours.

Lentiviral particles were produced in packing HEK-293T cells by cotransfection of pCMV-dR8.2-dvpr and plasmid cytomegalovirus pCMV-VSVG packaging plasmids along with scrambled (SCR) or anti-KLC2 short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) cloned in MISSION pLKO.1-puro plasmid (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously reported (20). Thyroid cell lines cells were transduced with lentiviral particles in growth media supplemented with 6 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) and stable cell clones were generated in the presence of 1 μg/ml puromycin (Thermo-Fisher Scientific).

125Iodide Transport Assays

Cells were incubated in Hank’s balanced salt solution containing 10 μM iodide supplemented with 50 μCi/μmol carrier-free 125iodide (PerkinElmer Sciences) for 30 minutes at 37 °C (21). NIS-specific iodide uptake was assessed in the presence of 40 μM perchlorate. Radioiodide accumulated in the cells was extracted with ice-cold ethanol and quantified in a Triathler Gamma Counter (Hidex). The amount of DNA was determined by the diphenylamine method after trichloroacetic acid precipitation (22). Results were expressed as picomoles of iodide per microgram DNA, and standardized by the ratio of the percentage of mutant NIS-positive cells to the percentage of wild-type (WT) NIS-positive cells—both of which were determined by flow cytometry under permeabilized conditions, to correct for differences in transfection efficiency between samples.

Membrane vesicles were prepared as described elsewhere (23, 24). Aliquots containing 200 μg of protein were incubated with an equal volume of a solution containing 20 μM iodide (25 μCi/μmol carrier-free 125iodide), 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES; pH 7.5), and 200 mM NaCl. Reactions were quenched with 1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 250 mM KCl followed by filtration through 0.22-μm nitrocellulose filters (EMD Millipore). Iodide uptake was expressed as picomoles of iodide per milligram of protein, and standardized by transfection efficiency, as indicated earlier.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were fixed in 2% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5 μg/mL rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody (No. 11867423001, Roche Applied Science) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.2% human serum albumin for nonpermeabilized conditions, or an additional 0.2% saponin for permeabilized conditions (25). After washing, cells were incubated with 1 μg/mLAlexa-488–conjugated antirat antibody (A-11006, Molecular Probes). The fluorescence of approximately 5 × 104 events per tube was assayed in a BD FACSCanto Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). The relative plasma membrane expression of mutant NIS was calculated as the ratio (plotted as percentage of WT NIS) of the percentage of mutant NIS-positive cells assessed under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions to the percentage of WT NIS-positive cells assessed under the same conditions.

Immunofluorescence

Cells seeded onto glass coverslips were fixed in 2% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5 μg/mL rat monoclonal anti-HA and 2 μg/mL mouse monoclonal anti-SEKDEL epitope (sc-58774, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies in PBS containing 0.2% human serum albumin and 0.1% Triton X-100 (26). Secondary staining was performed with 2 μg/mL Alexa-488–conjugated antirat and Alexa-594–conjugated antimouse antibodies (A-11005, Molecular Probes). Nuclear DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes). Coverslips were mounted with FluorSave Reagent (EMD Millipore) and images were acquired on an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus America).

Deglycosylation Assays and Western Blot

Whole-cell lysates were deglycosylated with endo-β-acetylglucosaminidase H (Endo H) (New England BioLabs) in 50 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.5). Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electrotransfer to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotting were carried out as previously described (27). Membranes were blocked and incubated with 0.25 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal antihuman or antirat NIS antibodies (28, 29), 1 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (sc-8334, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or 1 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-KLC2 primary antibody (HPA040416, Atlas Antibodies). After washing, membranes were further incubated with 0.07 μg/mL IRDye 680RD–conjugated antirabbit secondary antibody (No. 926-68071, LI-COR Biosciences). Membranes were visualized and quantified by Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Loading levels were determined by stripping and reprobing the same blot with 1 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH (anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) primary antibody (sc-25778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Green Fluorescent Protein Pull-Down Assays

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 20 mM CHAPS, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10% glycerol. After centrifugation, cleared cell extracts were incubated with GFP-Trap beads (Chromotek) for 4 hours at 4 °C under rotation. Beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer and bound proteins were eluted by heating at 75 °C in Laemmli sample buffer.

Proximity Ligation Assay

Cells seeded onto glass coverslips were fixed in methanol for 20 minutes at –20 °C and stained with 1 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal antihuman NIS antibody and 4 μg/mL mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (No. 11814460001, Roche Applied Science) diluted in antibody diluent solution. A Duolink proximity ligation assay (Olink Bioscience) was performed as per the manufacturer’s recommendations using Texas red fluorophore. DAPI-containing mounting medium was used to mount coverslips. Images were collected using a Leica DMi8 inverted fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Structural Modeling and Bioinformatic Analysis

Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT), Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2), and MutationTaster2 algorithms integrated in the Alamut Suite version 2.15.0 (Interactive Biosoftware) were used to predict the impact of the missense variant. Short linear motifs were predicted using the Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource (ELM; http://elm.eu.org). A structural human NIS homology model, comprising residues M1 to T571, using as a template the crystal structure of the Vibrio parahaemolyticus sodium/glucose cotransporter (PDB ID: 2XQ2) (30) and Microbacterium liquefaciens benzyl-hydantoin transporter (PDB ID: 2JLN) (31), and tryptophan-acidic motif NIS-containing peptide complexed with the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains of KLC2 (PDB ID: 3ZFW) (16) were built using MODELLER software. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the Amber molecular dynamics package and force field in explicit water using default parameters. The interaction of NIS peptides complexed with KLC2TPR domains were simulated for 100 ns without restraints. Short helical segments were simulated for 100 ns fixing residues 541 to 550 in helical conformation. Images were prepared using Visual Molecular Dynamics software.

Zebrafish Animal Model

The zebrafish research protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Facultad de Ciencias Bioquímicas y Farmacéuticas, Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Rosario, Argentina. Standard negative control morpholino (MO-GLO) and splice-blocking morpholino targeting the exon 2 donor splice site of the zebrafish klc2 gene (MO-klc2-SP) were as reported elsewhere (32). Morpholinos were synthesized by Gene Tools. One- to 2-cell stage embryos were microinjected with morpholinos at doses of 4 ng/embryo. Alternatively spliced KLC2 transcript was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of reverse transcriptase–PCR amplicons generated with the flanking primers 5′-CCACATTAGAAGTTTGAACCCCATCC (sense) and 5′-GTTGGGTATTCGCCAGCTCG (antisense) at 48 and 120 hours post fertilization (hpf).

Whole-mount immunofluorescence was carried out as previously reported (33). Briefly, 120-hpf larvae were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde overnight, treated with 10 μg/mL proteinase K, blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, 1% dimethylsulfoxide, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5% horse serum, and 0.8% Triton X-100 (blocking buffer), and incubated overnight in blocking buffer containing rabbit polyclonal anti-Tg antibody (A0251, Dako Corporation) or rabbit polyclonal anti-L-thyroxine-BSA (MFCD00164678, MP Biochemicals) primary antibodies. After several washing steps in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 1% BSA, larvae were incubated overnight with Alexa-488–conjugated antirabbit secondary antibody (A-11008, Molecular Probes). Whole-mount imaging of stained specimens embedded in 3% methylcellulose was performed using a Leica DMi8 inverted fluorescent microscope.

Whole-body of zebrafish larvae were homogenized (30 larvae for each replicate, n = 3-4 replicates), and total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Complementary DNA synthesis was performed by using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) using 2 μg RNA as template. Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) as described elsewhere (34). Validated gene-specific primer sets were as previously reported (35, 36). Relative changes in gene expression were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method normalized against the expression of the endogenous housekeeping gene elongation factor 1-α. Melting curve analyses were performed to validate the specificity of the PCR amplifications. The specificity of the reactions was determined by a melting curve analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical tests were performed using Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software). Multiple-group analysis was conducted by nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn multiple-comparisons post hoc test. Comparison between two groups was assessed by Mann-Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant at P less than .05.

Results

Identification of Homozygous SLC5A5 Missense Variant p.G561E

ITD was suspected in the propositus on the basis of congenital hypothyroidism and reduced 99mTc-pertechnectate accumulation in a normally located thyroid gland. The propositus’ SLC5A5 gene (GenBank Reference Sequence NM_000453) sequencing revealed a novel homozygous missense variant in exon 14: c.1.682G > A, p.G561E (Fig. 1A). This variant has been reported in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (rs1258025735) in heterozygosis showing a minor allele frequency of 8.01e-6, according to The Genome Aggregation Database. However, its pathophysiological significance was unknown. In silico analysis of the pathogenic impact of this variant yielded conflicting results: PolyPhen-2, benign (score: 0.4; scale: 0 = benign, 1 = probably damaging), MutationTaster2, disease-causing (P value: 1.0; P value for prediction confidence: 0 = low confidence, 1 = high confidence), and SIFT, tolerated (score: 0.51; scale: 1 = tolerated, 0 = deleterious). The parents were not available for genetic analysis.

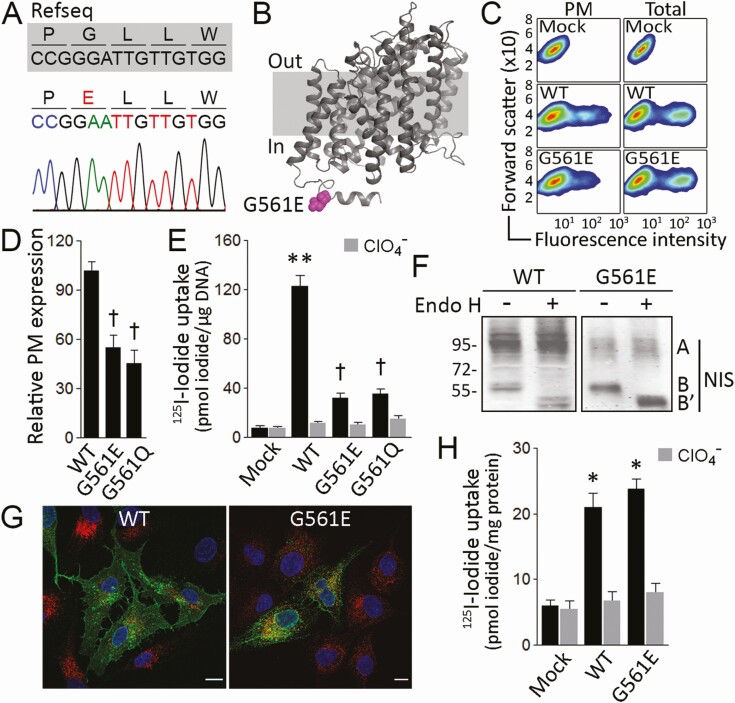

Figure 1.

G561E severely reduces sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) plasma membrane expression. A, Chromatogram showing a 15-bp fragment of NIS-coding exon 14 (nucleotides + 1.678 to + 1.692). The reference sequence (Refseq) is indicated in gray; the variant p.G561E is indicated in red. B, NIS homology model highlighting the cytosol-facing residue E561 in magenta. C, Representative flow cytometry analysis (pseudo-color density plot, forward scatter vs fluorescence intensity) of NIS expression at the plasma membrane (PM) and whole-cell (total) in cells permanently expressing vector (Mock), wild-type (WT) or G561E NIS. D, Relative WT or mutant NIS expression at the plasma membrane assessed by flow cytometry under nonpermeabilized conditions. Data are mean ± SEM. †P < .05 vs WT NIS-transfected cells (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn post hoc test). E, Steady-state iodide uptake in cells permanently expressing WT, G561E, or G561Q NIS. Results are expressed in pmol iodide/μg DNA ± SEM. **P < .01 vs mock-transfected cells, †P < .05 vs WT NIS-transfected cells (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn post hoc test). F, Endo-β-acetylglucosaminidase H (Endo H) treatment of whole-cell lysates from cells expressing WT or G561E NIS. Labels indicate the relative electrophoretic mobilities of the corresponding NIS polypeptides (A: Endo H resistant, fully glycosylated; B and B’: Endo H sensitive, partially glycosylated before and after Endo H digestion) depending on glycosylation status. G, Confocal microscopy analysis of permeabilized cells expressing WT or G561E NIS. Nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). The overlay of green (NIS) and red (KDEL) channels is shown. Scale bar: 10 μm. H, Iodide uptake in membrane vesicles prepared from cells expressing empty vector (Mock), WT, or G561E NIS. Results are expressed as pmol iodide/mg protein ± SEM. *P < .05 vs mock-transfected cells (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn post hoc test).

G561E Severely Impairs Sodium/Iodide Symporter Targeting to the Plasma Membrane

The residue G561 is located in the cytoplasm-facing carboxy-terminus (Fig. 1B). To functionally investigate the pathogenic impact of the G561E substitution, MDCK-II cells, which do not express NIS endogenously, were stably transfected with WT or G561E NIS expression vectors. Flow cytometry analysis in nonpermeabilized cells showed that the levels of G561E NIS at the plasma membrane were significantly lower than those of WT NIS (Fig. 1C and 1D). By contrast, the analysis in permeabilized cells showed similar expression levels for both proteins (see Fig. 1C). Moreover, to ascertain whether the intracellular retention of G561E NIS was due to the negatively charged Glu, we replaced G561 with the polar noncharged residue Gln. Although properly expressed, G561Q NIS, like G561E, did not reach the plasma membrane efficiently (see Fig. 1D). Consistent with this, iodide uptake assays revealed that both G561E and G561Q NIS-expressing cells exhibited modest perchlorate-sensitive iodide accumulation, compared to that of WT NIS-expressing cells (Fig. 1E). Together, these findings indicate that the G561E substitution decreases NIS targeting to the plasma membrane, and consequently reduces NIS-mediated iodide transport.

On Western blots, the fully glycosylated (~90-100 kDa) NIS polypeptide was barely detectable in G561E NIS-expressing cells, indicating that only a small percentage of the mutant protein is fully glycosylated (Fig. 1F). Consistent with this observation, most G561E NIS was sensitive to Endo H, indicating that the mutant protein is retained before it can reach the medial-Golgi (see Fig. 1F). The electrophoretic pattern of WT NIS, by contrast, showed a higher ratio of fully glycosylated (~90-100 kDa) to Endo H-sensitive, partially glycosylated (~60 kDa) polypeptides (see Fig. 1F). Additionally, using confocal microscopy, colocalization experiments with the endogenous ER marker retention signal KDEL indicated that G561E NIS was mostly intracellularly located and retained in the ER, whereas WT NIS was mostly expressed at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1G).

In intact cells, iodide transport is observed only when NIS is properly expressed at the plasma membrane. G561E NIS-expressing cells exhibited modest iodide uptake, ultimately because G561E NIS was mostly retained intracellularly. To determine whether G561E NIS is intrinsically active, we measured iodide transport in membrane vesicles (23, 24), which contain sealed membranes from all intracellular organelles, except the nucleus, as well as from the plasma membrane. Strikingly, membrane vesicles from cells expressing G561E NIS accumulated as much iodide as those prepared from cells expressing WT NIS (Fig. 1H), indicating that, although G561E NIS transport to the plasma membrane is severely reduced, the protein itself is properly folded and highly functional. Moreover, this result demonstrates that a negatively charged residue at position 561 does not affect NIS overall folding or activity; rather, the replacement of a small neutral residue (Gly) with a larger, negatively charged one (Glu) may interfere with interacting proteins that are essential for NIS transport to the plasma membrane.

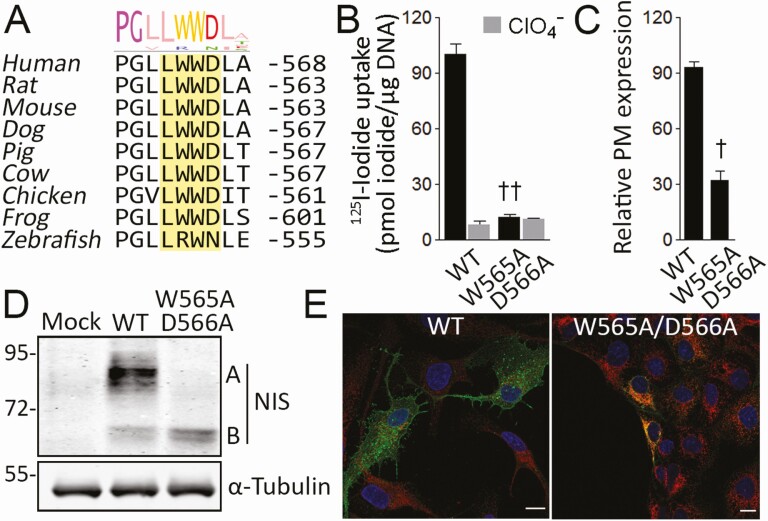

A Conserved Tryptophan-Acidic Sorting Motif Is Needed for Sodium/Iodide Symporter to Exit the Endoplasmic Reticulum

Recently, we demonstrated that the NIS carboxy-terminal segment from I546 to E578 is required for NIS ER exit, and subsequent transport to the plasma membrane (37). Significantly, in silico analysis revealed a putative highly conserved tryptophan-acidic sorting motif [L/M] × W[D/E] formed by residues L563 to D566 flanking the mutated residue G561 (Fig. 2A). To investigate the participation of the tryptophan-acidic motif in NIS ER exit, we generated MDCK-II cells stably expressing the NIS mutant W565A/D566A to disrupt the putative sorting motif. Significantly, W565A/D566A NIS-expressing MDCK-II cells did not exhibit perchlorate-sensitive iodide accumulation (Fig. 2B). Consistent with this, flow cytometry analysis, under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions, revealed that, although properly expressed, W565A/D566A NIS did not reach the plasma membrane efficiently (Fig. 2C). On Western blots, the electrophoretic pattern of W565A/D566A NIS showed only the partially glycosylated (∼60 kDa) polypeptide, indicating that the mutant protein matures only partially (Fig. 2D). Consistent with this observation, colocalization experiments with the ER marker KDEL demonstrated that W565A/D566A NIS was retained in the ER (Fig. 2E). Together, these findings indicate that the tryptophan-acidic motif, which is highly conserved across species, is critical for NIS ER exit.

Figure 2.

A conserved tryptophan-acidic motif is required for sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) endoplasmic reticulum (ER) exit. A, Multiple NIS sequences alignment. The conserved tryptophan-acidic motif in the NIS carboxy-terminus is highlighted. Sequence logo represents degree of conservation. B, Steady-state iodide uptake in cells permanently expressing wild-type (WT) or W565A/D566A NIS. Results are expressed in pmol iodide/μg DNA ± SEM. ††P < .01 vs WT NIS-transfected cells (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn post hoc test). C, Relative WT or mutant NIS expression at the plasma membrane assessed by flow cytometry. Data are mean ± SEM. †P < .05 vs WT NIS-transfected cells (Mann-Whitney U test). D, Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates from cells expressing WT or W565A/D566A NIS. Labels indicate the relative electrophoretic mobilities of the corresponding NIS polypeptides (A: Fully glycosylated; B: partially glycosylated) depending on glycosylation status. α-tubulin is shown as a loading control. E, Confocal microscopy analysis of permeabilized cells expressing WT or W565A/D566A NIS. Nuclei were stained with ′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). The overlay of green (NIS) and red (KDEL) channels is shown. Scale bar: 10 μm.

G561E Interferes With the Interaction Between Sodium/Iodide Symporter and the Adapter Kinesin Light Chain 2

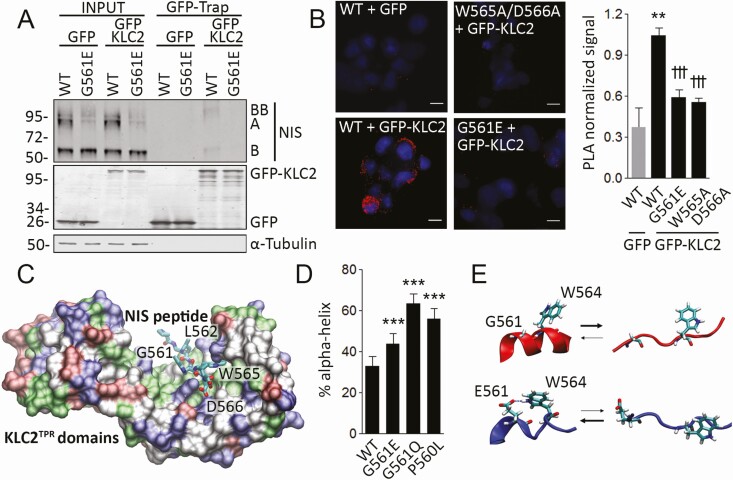

Microtubule motors drive bidirectional intracellular ER-to-Golgi transport (38). The motor protein kinesin-1, a heterotetramer composed of Kif5 kinesin heavy chain and KLC homodimers, is required for ER protein export and anterograde ER-to-Golgi transport (39). Tryptophan-acidic motifs are KLC-dependent kinesin-1 cargo–binding motifs (16, 40). Based on The Human Protein Atlas database (www.proteinatlas.org), the most abundant KLC isoform in the thyroid is the ubiquitously expressed KLC2. Therefore, we investigated the physical interaction between NIS and KLC2 by carrying out GFP-Trap-based coimmunoprecipitation experiments in HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with WT or G561E NIS, and GFP or GFP-KLC2. Western blot analysis of GFP-KLC2 eluates in WT NIS-expressing cells revealed monomers (~60 kDa, band B) and dimers (~100–120 kDa, band BB) of partially glycosylated NIS polypeptides (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the anterograde ER-to-Golgi transport of NIS is mediated by direct interaction with KLC2. Moreover, we observed that G561E severely reduced the physical interaction between NIS and KLC2 (see Fig. 3A). To further analyze this interaction, we carried out proximity ligation assays (PLAs) in HEK-293T cells transiently coexpressing WT, W565A/D566A, or G561E NIS along with GFP or GFP-KLC2. In agreement with the results of the coimmunoprecipitation experiments, the PLA signal was detected in cells coexpressing WT NIS and GFP-KLC2, but not in those expressing GFP alone (Fig. 3B). In contrast, a significant reduction in PLA signal was detected in cells coexpressing W565A/D566A or G561E NIS and GFP-KLC2 (see Fig. 3B). Taken together, our data indicate that the tryptophan-acidic motif is required for NIS to interact with KLC2, and that the G561E substitution interferes with the interaction between NIS and KLC2.

Figure 3.

G561E interferes with the interaction between sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) and kinesin-1 light chain 2. A, Immunoprecipitation of green fluorescent protein (GFP) with GFP-Trap technology using whole-cell lysates from type II Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK-II) cells permanently expressing wild-type (WT) or G561E NIS and transiently transfected with GFP or GFP-KLC2. Labels indicate the relative electrophoretic mobilities of the corresponding GFP-Trap pulled-down NIS polypeptides (A: Fully glycosylated; B and BB: monomer and dimer of partially glycosylated) depending on glycosylation status. Labels on the right side of the blot indicate the relative electrophoretic mobilities of the corresponding NIS polypeptides. Undetectable α-tubulin protein levels demonstrate the absence of cytoplasmic contamination in GFP-Trap pull-downs. B, Proximity ligation assay (PLA) in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells cotransfected with WT, W565A/D566A, or G561E NIS along with GFP or GFP-KLC2. **P < .01 vs WT + GFP, †††P < .001 vs WT + GFP-KLC2 (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn post hoc test). Scale bar: 10 μm. C, Tryptophan-acidic motif-containing NIS octapeptide P560-L567 bound to the KLC2 tetratricopeptide (KLC2TPR) domains represented as a molecular surface colored by residue type. D, Percentage of α-helix structure adopted by WT, G561E, G561Q, and P560L NIS octapeptides P560-L567 during the molecular dynamic simulation. ***P < .001 (analysis of variance, Bonferroni post hoc test). E, Structural equilibrium of WT (red) or G561E (blue) octapeptide P560-L567. A putative hydrogen bond between residues E561 and W564 is indicated.

We performed computer simulations to gain structural insights into the interaction between the tryptophan-acidic motif-containing human NIS octapeptide P560-L567 and the KLC2 tetratricopeptide repeat (KLC2TPR) domains (Fig. 3C). We built the corresponding complex using as template the crystal structure of mouse KLC2TPR domains bound to a SifA-kinesin interacting protein peptide containing a tryptophan-acidic motif (16). Molecular dynamic (MD) simulations showed that the KLC2TPR domains form a stable complex with NIS octapeptide bound in an extended conformation. As expected (16), NIS peptide residues L563, W565, and D566 were embedded into a concave groove formed by KLC2TPR domains 2, 3, and 4. Significantly, MD simulations revealed that the mutant NIS peptide E561 also binds to KLC2TPR domains, but the peptide W565A missing the tryptophan-acidic motif does not. Visual inspection of the trajectories showed no significant differences between WT and E561 NIS peptides complexed with KLC2TPR. These observations are not quite unexpected, as the side chain of E561 does not directly participate in the interaction between KLC2 and the cargo peptide (see Fig. 3C); thus, a subtle change in the NIS-KLC2 interaction surface does not explain the pathogenicity of G561E.

Tryptophan-acidic motifs are recognized in the background of unstructured peptides (16); therefore, we analyzed the effect of the mutant G561E on the intrinsic structure of the peptide containing the tryptophan-acidic motif. Molecular modeling and analysis of secondary structure predictors suggested that the sequence 552 to 565 forms a short helix preceded by a highly conserved Pro-Gly pair (Fig. 2A) that favors the unstructured conformation required for KLC2 interaction. Considering that the presence of E561 might shift the equilibrium toward a helical conformation unable to interact with KLC2, we performed MD simulations of WT and E/Q561 peptides starting from a complete helical conformation. On the time scale of the simulation, the E561-containing peptide adopts an α-helix secondary structure 44% of the time, whereas the WT peptide adopts one 33% of the time (Fig. 3D). Accordingly, the variant Q561 also favors the helical structure of the peptide that hides the tryptophan-acidic motif, causing G561Q NIS to be retained intracellularly (see Fig. 3D). Moreover, Yamaguchi et al (41) recently reported the heterozygous P560L NIS variant in a patient with oligogenic thyroid dyshormonogenesis. Consistently with the importance of the Pro-Gly pair favoring the unstructured conformation of the tryptophan-acidic motif, the variant L560 also favors a helical conformation (see Fig. 3D). Additionally, MD simulations predicted a frequent hydrogen bond interaction between E561 and the tryptophan residue W564 in the mutant peptide that might contribute to the stability of the α-helical conformation hindering the recognition of the tryptophan-acidic motif by KLC2 (Fig. 3E). In summary, based on our structural bioinformatic analysis, we hypothesized that G561E might shift the equilibrium of the unstructured tryptophan-acidic motif toward a more structured conformation unable to be recognized by KLC2.

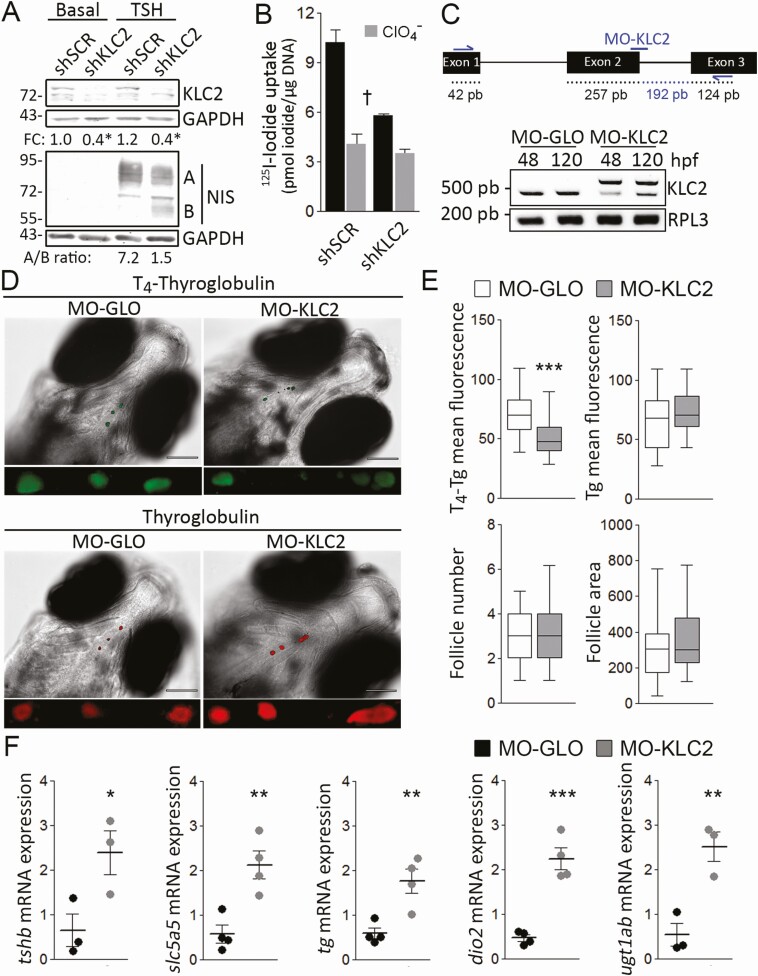

Role of Kinesin Light Chain 2 in Normal Thyroid Hormonogenesis

To ascertain the relevance of KLC2 for adequate iodide uptake in thyroid follicular cells, we knocked down Klc2 expression using shRNA in PCCl3 thyroid cells, which express NIS endogenously. Western blot analysis revealed a significant knockdown of KLC2 protein levels in KLC2 shRNA-transduced cells, compared to those of SCR shRNA-transduced cells (Fig. 4A). Although García et al (42) reported that TSH regulates the expression of ER-Golgi transport factors involved in the secretory pathway, we saw no evidence that TSH treatment induces KLC2 protein expression in SCR shRNA-transduced PCCl3 cells (see Fig. 4A). As previously reported (43), TSH stimulation increased NIS protein expression, maturation, and transport to the plasma membrane in thyroid cells. In TSH-stimulated Klc2 knockdown cells, we observed defective NIS maturation, as revealed by a reduced ratio of fully glycosylated (~90-100 kDa) to partially glycosylated (~60 kDa) NIS polypeptides (see Fig. 4A). Consistent with this, Klc2 knockdown significantly decreased NIS-mediated perchlorate-sensitive iodide accumulation (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained using FRTL-5 thyroid cells (44). Together, these results suggest that KLC2 is required for NIS anterograde kinesin-1–dependent ER-to-Golgi transport, and consequently NIS plasma membrane expression and iodide accumulation.

Figure 4.

KLC2 knockdown reduced thyroid hormonogenesis due to defective sodium/iodide symporter (NIS)-mediated iodide accumulation. A, Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates from scrambled (SCR) or Klc2 short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-transfected PCCl3 cells in response to thyrotropin (TSH) treatment for 48 hours. Labels indicate the relative electrophoretic mobilities of the corresponding NIS polypeptides (A: Fully glycosylated; B: partially glycosylated) depending on glycosylation status. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression was used as loading control. *P < .05 vs SCR shRNA-transfected cells (Mann-Whitney U test). Fold change (FC) represents the mean from 3 independent experiments. B, Steady-state iodide uptake in SCR or Klc2 shRNA-transfected PCCl3. Results are expressed in pmol iodide/μg DNA ± SEM. †P < .05 vs SCR shRNA-transfected cells (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn post hoc test). C, Partial schematic representation of the klc2 gene. Anti-klc2 morpholino (MO-KLC2) and primer hybridization’s sites are indicated. Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assessing KLC intron 2 inclusion in control (MO-GLO) or anti-klc2 (MO-KLC2) morpholino-microinjected larvae at 48 and 120 hpf. The expression of rpl-3 was used as loading control. D, Representative whole-mount immunofluorescence assessing thyroglobulin (Tg)-bound thyroxine (T4-Tg) and Tg in embryos microinjected with MO-GLO or MO-KLC2 at 120 hpf. Scale bar: 100 μm. Close-up shows representative selection of immunostainings (magnified ventral views of thyroid region). E, Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity of T4-Tg and Tg, and number and cross-section area (μm2) of T4-Tg immunoreactive follicles in embryos microinjected with MO-GLO or MO-KLC2 at 120 hpf. ***P < .001 vs MO-GLO–microinjected larvae (Mann-Whitney U test). The number of larvae analyzed per condition was 35. F, Relative whole-body messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of genes related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in MO-GLO– or MO-KLC2–microinjected embryos at 120 hpf. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs MO-GLO–microinjected larvae (Mann-Whitney U test). The number of larvae analyzed per replicate was 30.

Hence, considering the importance of NIS-mediated iodide uptake for thyroid hormone synthesis, we investigated the relevance of Klc2 in thyroid physiology in vivo using zebrafish larvae. Using a splice-blocking morpholino that abrogates zebrafish klc2 messenger RNA intron 2 splicing (MO-klc2-SP) leading to p.I78Kfs10* Klc2, we knocked down klc2 functional expression (Fig. 4C). We then analyzed Tg-bound thyroxine (T4-Tg) and Tg levels in the colloid of thyroid follicles of zebrafish larvae microinjected with control (MO-GLO) or MO-klc2-SP morpholinos (MO-KLC2) at 120 hpf. Whole-mount immunofluorescence analysis revealed significantly reduced immunostaining for T4, but unaltered immunostaining for Tg in klc2 morphants, suggesting reduced thyroid hormone synthesis (Fig. 4D and 4E). We did not observe changes in the number and size of Tg-immunoreactive follicles (see Fig. 4E), indicating normal thyroid development. Moreover, we examined the transcription of genes involved in the pituitary-thyroid axis. Consistently with a hypothyroid state, klc2 morphants showed upregulation of genes involved in thyroid follicular cell stimulation (TSH-β subunit, tshb), thyroid hormone biosynthesis (slc5a5, tg), and thyroid hormone metabolism (thyronine deiodinase 2, dio2 and UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family ab, ugt1ab). Altogether, our data demonstrate that KLC2 deficiency significantly decreases the synthesis of thyroid hormones leading to a hypothyroid state, most likely as a consequence of impaired NIS expression at the plasma membrane, leading to deficient accumulation of the iodide necessary for thyroid hormonogenesis, thus demonstrating that KLC2 is needed for adequate thyroid hormonogenesis.

Discussion

Here, we have reported the identification of a novel homozygous SLC5A5 missense and pathogenic G561E variant in an Argentinian pediatric patient diagnosed with dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism due to defective iodide transport. The G561E substitution lies in the carboxy-terminus of NIS, which is required for the expression of the symporter at the plasma membrane (37). Underscoring the significance of the carboxy-terminal region, we have reported the pathogenic S547R variant, which causes the intracellular retention of the mutant protein (45). Importantly, the mutations in NIS that cause the transporter to be retained intracellularly are not restricted to the carboxy-terminal region (46). Moreover, although the mechanisms preventing proper NIS function remain to be identified, nonsense homozygous R636* and heterozygous Q639* NIS variants were detected in patients with hypoplastic thyroid glands and congenital hypothyroidism (47, 48). Interestingly, Darrouzet et al (49) reported a putative carboxy-terminal postsynaptic density 95/disc large/zonula occludens-1 (PDZ)-binding short linear motif [S/T]xΦ COOHthat, in other transmembrane proteins, is involved in their expression at the plasma membrane (50-53). Although the insertion of a carboxy-terminal epitope tag does not have any major effect on NIS targeting to the plasma membrane (54, 55), the role of the putative PDZ-binding motif remains to be determined.

Functional characterization of G561E NIS revealed a dramatic reduction in perchlorate-sensitive iodide uptake. Of note, in vitro data correlate with the clinical observation of reduced 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake when the patient was examined by thyroid scintigraphy. Considering that NIS-mediated iodide uptake is the initial step in the synthesis of the iodine-containing thyroid hormones, our results indicate that the G561E substitution impairs normal iodide uptake by interfering with NIS maturation and transport to the plasma membrane, not with the intrinsic activity of the protein. Therefore, the consequent lack of sufficient NIS molecules at the basolateral plasma membrane in the thyroid follicular cells reveals the mechanism underlying the deficient accumulation of iodide that leads to dyshormonogenic hypothyroidism. Patients with congenital hypothyroidism due to deficient accumulation of iodide show a substantial clinical and biochemical heterogeneity (56). Under conditions of iodine sufficiency, thyroid function at diagnosis reflects differences in residual mutant NIS protein activity. The thyroid function of our propositus was sufficient to conserve normal thyroid hormone levels though they were at the lower end of the normal range for his age. This could be due residual G561E NIS activity (which was detected by 99mTc-pertechnetate thyroid scintigraphy). In this context, the increase in TSH levels following a decrease in thyroid hormone production may partially overcome the defect in G561E NIS transport to the plasma membrane by upregulating NIS transcription, as has been observed in patients with different NIS loss-of-function variants (57, 58). Interestingly, the impaired targeting of G561E NIS to the cell surface is not due to a negatively charged residue, as G561Q also results in defective NIS expression at the plasma membrane.

A thorough in vitro characterization of the molecular mechanism underlying G561E NIS defective transport to the plasma membrane led to surprising findings. We identified a conserved tryptophan-acidic motif formed by residues L563 to D566—flanking the mutated residue G561—required for NIS ER exit. We have further extended our work by investigating the role of the kinesin-1 KLC2 subunit that binds to tryptophan-acidic motifs in NIS transport to the plasma membrane. Based on computer simulations and biochemical analyses, we hypothesized that G561E favors a helical secondary structure that hinders the recognition of the tryptophan-acidic motif by KLC2, thus abrogating mutant NIS ER exit, and its subsequent transport to the plasma membrane. Interestingly, Vacic et al (59) demonstrated that 20% of disease-associated missense mutations mapped to intrinsically disordered protein regions induce disorder-to-order transitions, thus likely disrupting functions that require protein disorder, such as recognition of short linear sorting motifs (60).

Microtubule transport defects due to mutations in microtubule-based motors, that is, kinesins, dynein and its accessory protein dynactin, or microtubules themselves are associated with several diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders (61). However, the role of microtubule-based motors along endocytic and secretory pathways in the thyroid follicular cell remains uncertain. D’Amico et al (62) investigated the role of the heterotrimeric kinesin-2 molecular motor complex subunit KIF3A in thyroid follicular cells. Thyroid-specific Kif3a-deficient mice developed mild hypothyroidism caused by a putative defect in TSH receptor transport to the basolateral membrane of thyroid follicular cells and, consequently, a deficient TSH signaling pathway. Here, we ruled out a defective TSH signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of the mutant phenotype since NIS protein expression is unaltered in TSH-stimulated KLC2 knockdown PCCl3 cells. Moreover, recently, Stoupa et al (63) reported that mutations in the β-tubulin isotype I gene TUBB1 cause thyroid dysgenesis associated with abnormal platelet function. Here, we discovered that the kinesin-1 KLC2 subunit plays a role in thyroid hormonogenesis. We provided evidence that knocking down KLC2 impairs the maturation of NIS and its expression at the plasma membrane, leading to insufficient accumulation of the iodide needed to synthesize the thyroid hormones. To date, no disease-associated loss-of-function mutations in human KLC2 have been reported. However, Ingham et al (64) identified Klc2 as a gene underlying progressive sensorineural hearing loss in mice. Moreover, a homozygous gain-of-function mutation in human KLC2 causes SPOAN syndrome, a neurodegenerative disorder that consists of spastic paraplegia, optic atrophy and neuropathy (32).

Not only does NIS play a key role in thyroid hormonogenesis, but also, NIS-mediated radioiodide therapy provides the molecular basis for theranostic procedures for differentiated thyroid carcinomas (65). The efficacy of radioiodide therapy ultimately depends on functional NIS expression at the plasma membrane. Immunohistochemical analyses have shown that, in thyroid cancer cells, NIS is frequently located in intracellular compartments, suggesting impaired transport of NIS to the plasma membrane (66). From a therapeutic perspective, interventions allowing more NIS molecules to reach the plasma membrane of tumor cells would dramatically improve the efficacy of radioiodide therapy. Recently, Fletcher et al (67) showed that inhibiting the NIS-interacting protein known as valosin-containing protein increases NIS expression at the plasma membrane and radioiodide accumulation in thyroid cancer models. In view of the role that KLC2 plays in NIS plasma membrane expression, it will be of interest to ascertain whether unregulated posttranslational modifications impairing NIS/KLC2 interaction cause NIS to be retained intracellularly in thyroid tumors, which would lead to radioiodide resistance. If so, a deeper understanding of this phenomenon may enable us to develop novel strategies for restoring radioiodide accumulation in thyroid cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mark Dodding (King’s College London) for providing GFP-tagged KLC2 expression vector. We also thank Dr Carlos Mas and Dr Pilar Crespo (Centro de Micro y Nanoscopía de Córdoba, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba) for imaging technical assistance.

Financial Support: M.M. was partially supported by international traveling fellowships from The Company of Biologists’ Journal of Cell Science and The International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. This work was supported by fellowships and research grants from Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica—Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Nos. PICT-2014-0726, PICT-2015-3839, PICT-2015-3705, and PICT-2018-1596 to J.P.N.), Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología—Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Nos. 30820150100222CB and 33620180100772CB to J.P.N.), Instituto Nacional del Cáncer—Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social, American Thyroid Association–Thyroid Cancer Survivors’ Association (No. 2015-033 to J.P.N.), and the National Institutes of Health (grant No. DK-41544 to N.C.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- ClO4–

perchlorate

- DAPI

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- Endo H

endo-β-acetylglucosaminidase H

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- ITD

iodide transport defect

- KLC2

kinesin light chain 2

- MD

molecular dynamic

- MDCK-II

type II Madin–Darby canine kidney

- MO-GLO

control morpholino

- NIS

sodium/iodide symporter

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PLA

proximity ligation assay

- SCR

scrambled

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- T4

thyroxine

- Tg

thyroglobulin

- TPR

tetratricopeptide repeat

- TSH

thyrotropin

- WT

wild-type

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in “References.”

References

- 1. Szinnai G. Genetics of normal and abnormal thyroid development in humans. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;28(2):133-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fujiwara H, Tatsumi K, Miki K, et al. Congenital hypothyroidism caused by a mutation in the Na+/I– symporter. Nat Genet. 1997;16(2):124-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsuda A, Kosugi S. A homozygous missense mutation of the sodium/iodide symporter gene causing iodide transport defect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(12):3966-3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicola JP, Carrasco N, Masini-Repiso AM. Chapter one—Dietary I– absorption: expression and regulation of the Na+/I– symporter in the intestine. Vitam Horm. 2015;98:1-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martín M, Geysels RC, Peyret V, Bernal Barquero CE, Masini-Repiso AM, Nicola JP.. Implications of Na+/I– symporter transport to the plasma membrane for thyroid hormonogenesis and radioiodide therapy. J Endoc Soc. 2019;3(1):222-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ravera S, Quick M, Nicola JP, Carrasco N, Amzel LM. Beyond non-integer Hill coefficients: A novel approach to analyzing binding data, applied to Na+-driven transporters. J Gen Physiol. 2015;145(6):555-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nicola JP, Carrasco N, Amzel LM. Physiological sodium concentrations enhance the iodide affinity of the Na+/I– symporter. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nicola JP, Reyna-Neyra A, Saenger P, et al. Sodium/iodide symporter mutant V270E causes stunted growth but no cognitive deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(10):E1353-E1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paroder V, Nicola JP, Ginter CS, Carrasco N. The iodide-transport-defect-causing mutation R124H: a δ-amino group at position 124 is critical for maturation and trafficking of the Na+/I– symporter. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 15):3305-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li W, Nicola JP, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. Asn441 plays a key role in folding and function of the Na+/I– symporter (NIS). FASEB J. 2013;27(8):3229-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paroder-Belenitsky M, Maestas MJ, Dohán O, et al. Mechanism of anion selectivity and stoichiometry of the Na+/I– symporter (NIS). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(44):17933-17938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De la Vieja A, Reed MD, Ginter CS, Carrasco N. Amino acid residues in transmembrane segment IX of the Na+/I– symporter play a role in its Na+ dependence and are critical for transport activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(35):25290-25298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Llorente-Esteban A, Manville RW, Reyna-Neyra A, Abbott GW, Amzel LM, Carrasco N.. Allosteric regulation of mammalian Na+/I– symporter activity by perchlorate. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:533-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sobrero G, Muñoz L, Bazzara L, et al. Thyroglobulin reference values in a pediatric infant population. Thyroid. 2007;17(11):1049-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicola JP, Nazar M, Serrano-Nascimento C, et al. Iodide transport defect: functional characterization of a novel mutation in the Na+/I– symporter 5′-untranslated region in a patient with congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):E1100-E1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pernigo S, Lamprecht A, Steiner RA, Dodding MP. Structural basis for kinesin-1:cargo recognition. Science. 2013;340(6130):356-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peyret V, Nazar M, Martín M, et al. Functional toll-like receptor 4 overexpression in papillary thyroid cancer by MAPK/ERK-induced ETS1 transcriptional activity. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(5):833-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. del Mar Montesinos M, Nicola JP, Nazar M, et al. Nitric oxide-repressed Forkhead factor FoxE1 expression is involved in the inhibition of TSH-induced thyroid peroxidase levels. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;420:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geysels RC, Peyret V, Martín M, et al. The transcription factor NF-κB mediates thyrotropin-stimulated expression of thyroid differentiation markers. Thyroid. 2021;31(2):299-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trucco LD, Andreoli V, Núñez NG, Maccioni M, Bocco JL. Krüppel-like factor 6 interferes with cellular transformation induced by the H-ras oncogene. FASEB J. 2014;28(12):5262-5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicola JP, Peyret V, Nazar M, et al. S-Nitrosylation of NF-κB p65 inhibits TSH-induced Na+/I– symporter expression. Endocrinology. 2015;156(12):4741-4754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferrandino G, Nicola JP, Sánchez YE, et al. Na+ coordination at the Na2 site of the Na+/I– symporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(37):E5379-E5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De la Vieja A, Ginter CS, Carrasco N. Molecular analysis of a congenital iodide transport defect: G543E impairs maturation and trafficking of the Na+/I– symporter. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(11):2847-2858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reyna-Neyra A, Jung L, Chakrabarti M, Suarez Mikel, Amzel LM, Carrasco N.. The iodide transport defect-causing Y348D mutation in the Na+/I– symporter (NIS) renders the protein intrinsically inactive and impairs its targeting to the plasma membrane. Thyroid. Published March 27, 2021. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purtell K, Paroder-Belenitsky M, Reyna-Neyra A, et al. The KCNQ1-KCNE2 K⁺ channel is required for adequate thyroid I⁻ uptake. FASEB J. 2012;26(8):3252-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peinetti N, Scalerandi MV, Cuello Rubio MM, et al. The response of prostate smooth muscle cells to testosterone is determined by the subcellular distribution of the androgen receptor. Endocrinology. 2018;159(2):945-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rossich LE, Thomasz L, Nicola JP, et al. Effects of 2-iodohexadecanal in the physiology of thyroid cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;437:292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tazebay UH, Wapnir IL, Levy O, et al. The mammary gland iodide transporter is expressed during lactation and in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):871-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levy O, Dai G, Riedel C, et al. Characterization of the thyroid Na+/I– symporter with an anti-COOH terminus antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(11):5568-5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Watanabe A, Choe S, Chaptal V, et al. The mechanism of sodium and substrate release from the binding pocket of vSGLT. Nature. 2010;468(7326):988-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weyand S, Shimamura T, Yajima S, et al. Structure and molecular mechanism of a nucleobase-cation-symport-1 family transporter. Science. 2008;322(5902):709-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melo US, Macedo-Souza LI, Figueiredo T, et al. Overexpression of KLC2 due to a homozygous deletion in the non-coding region causes SPOAN syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(24):6877-6885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Opitz R, Maquet E, Zoenen M, Dadhich R, Costagliola S. TSH receptor function is required for normal thyroid differentiation in zebrafish. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(9):1579-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scalerandi MV, Peinetti N, Leimgruber C, et al. Inefficient N2-like neutrophils are promoted by androgens during infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosas MG, Lorenzatti A, Porcel de Peralta MS, Calcaterra NB, Coux G. Proteasomal inhibition attenuates craniofacial malformations in a zebrafish model of Treacher Collins syndrome. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;163:362-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhai W, Huang Z, Chen L, Feng C, Li B, Li T.. Thyroid endocrine disruption in zebrafish larvae after exposure to mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP). PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martín M, Modenutti CP, Peyret V, et al. A carboxy-terminal monoleucine-based motif participates in the basolateral targeting of the Na+/I– symporter. Endocrinology. 2019;160(1):156-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gurel PS, Hatch AL, Higgs HN. Connecting the cytoskeleton to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Curr Biol. 2014;24(14):R660-R672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gupta V, Palmer KJ, Spence P, Hudson A, Stephens DJ. Kinesin-1 (uKHC/KIF5B) is required for bidirectional motility of ER exit sites and efficient ER-to-Golgi transport. Traffic. 2008;9(11):1850-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dodding MP, Mitter R, Humphries AC, Way M. A kinesin-1 binding motif in vaccinia virus that is widespread throughout the human genome. EMBO J. 2011;30(22):4523-4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yamaguchi T, Nakamura A, Nakayama K, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing for congenital hypothyroidism with positive neonatal TSH screening. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(8):e2825-e2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. García IA, Torres Demichelis V, Viale DL, et al. CREB3L1-mediated functional and structural adaptation of the secretory pathway in hormone-stimulated thyroid cells. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(24):4155-4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Riedel C, Levy O, Carrasco N. Post-transcriptional regulation of the sodium/iodide symporter by thyrotropin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):21458-21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Martín M, Modenutti CP, Gil Rosas ML, et al. Data from: A novel SLC5A5 variant reveals the crucial role of kinesin light chain 2 in thyroid hormonogenesis. figshare 2021. Deposited 12 April 2021. 10.6084/m9.figshare.14401874.v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martín M, Bernal Barquero CE, Geysels RC, et al. Novel sodium/iodide symporter compound heterozygous pathogenic variants causing dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2019;29(7):1023-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ravera S, Reyna-Neyra A, Ferrandino G, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. The sodium/iodide symporter (NIS): molecular physiology and preclinical and clinical applications. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79:261-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Makretskaya N, Bezlepkina O, Kolodkina A, et al. High frequency of mutations in ‘dyshormonogenesis genes’ in severe congenital hypothyroidism. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang H, Kong X, Pei Y, et al. Mutation spectrum analysis of 29 causative genes in 43 Chinese patients with congenital hypothyroidism. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22(1):297-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Darrouzet E, Graslin F, Marcellin D, et al. A systematic evaluation of sorting motifs in the sodium-iodide symporter (NIS). Biochem J. 2016;473(7):919-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perego C, Vanoni C, Villa A, et al. PDZ-mediated interactions retain the epithelial GABA transporter on the basolateral surface of polarized epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1999;18(9):2384-2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Petitprez S, Zmoos AF, Ogrodnik J, et al. SAP97 and dystrophin macromolecular complexes determine two pools of cardiac sodium channels Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011;108(3):294-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Reiners J, Nagel-Wolfrum K, Jürgens K, Märker T, Wolfrum U. Molecular basis of human Usher syndrome: deciphering the meshes of the Usher protein network provides insights into the pathomechanisms of the Usher disease. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(1):97-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Müller D, Kausalya PJ, Claverie-Martin F, et al. A novel claudin 16 mutation associated with childhood hypercalciuria abolishes binding to ZO-1 and results in lysosomal mistargeting. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(6):1293-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dayem M, Basquin C, Navarro V, et al. Comparison of expressed human and mouse sodium/iodide symporters reveals differences in transport properties and subcellular localization. J Endocrinol. 2008;197(1):95-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smith VE, Read ML, Turnell AS, et al. A novel mechanism of sodium iodide symporter repression in differentiated thyroid cancer. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 18):3393-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Szinnai G, Kosugi S, Derrien C, et al. Extending the clinical heterogeneity of iodide transport defect (ITD): a novel mutation R124H of the sodium/iodide symporter gene and review of genotype-phenotype correlations in ITD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(4):1199-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kosugi S, Sato Y, Matsuda A, et al. High prevalence of T354P sodium/iodide symporter gene mutation in Japanese patients with iodide transport defect who have heterogeneous clinical pictures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(11):4123-4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. De La Vieja A, Ginter CS, Carrasco N. The Q267E mutation in the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) causes congenital iodide transport defect (ITD) by decreasing the NIS turnover number. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 5):677-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vacic V, Markwick PR, Oldfield CJ, et al. Disease-associated mutations disrupt functionally important regions of intrinsic protein disorder. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(10):e1002709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fuxreiter M, Tompa P, Simon I. Local structural disorder imparts plasticity on linear motifs. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(8):950-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Franker MA, Hoogenraad CC. Microtubule-based transport—basic mechanisms, traffic rules and role in neurological pathogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 11):2319-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. D’Amico E, Gayral S, Massart C, et al. Thyroid-specific inactivation of KIF3A alters the TSH signaling pathway and leads to hypothyroidism. J Mol Endocrinol. 2013;50(3):375-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stoupa A, Adam F, Kariyawasam D, et al. TUBB1 mutations cause thyroid dysgenesis associated with abnormal platelet physiology. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10(12):e9569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ingham NJ, Pearson SA, Vancollie VE, et al. Mouse screen reveals multiple new genes underlying mouse and human hearing loss. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(4):e3000194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Reiners C, Hänscheid H, Luster M, Lassmann M, Verburg FA. Radioiodine for remnant ablation and therapy of metastatic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(10):589-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tavares C, Coelho MJ, Eloy C, et al. NIS expression in thyroid tumors, relation with prognosis clinicopathological and molecular features. Endocr Connect. 2018;7(1):78-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fletcher A, Read ML, Thornton CEM, et al. Targeting novel sodium iodide symporter interactors ADP-ribosylation factor 4 and valosin-containing protein enhances radioiodine uptake. Cancer Res. 2020;80(1):102-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in “References.”