Abstract

Context

Thyroid cancer is the second most common cancer in Hispanic women.

Objective

To determine the relationship between acculturation level and unmet information needs among Hispanic women with thyroid cancer.

Design

Population-based survey study.

Participants

Hispanic women from Los Angeles Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results registry with thyroid cancer diagnosed in 2014–2015 who had previously completed our thyroid cancer survey in 2017–2018 (N = 273; 80% response rate).

Main Outcome Measures

Patients were asked about 3 outcome measures of unmet information needs: (1) internet access, (2) thyroid cancer information resources used, and (3) ability to access information. Acculturation was assessed with the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH). Health literacy was measured with a validated single-item question.

Results

Participants’ median age at diagnosis was 47 years (range 20–79) and 48.7% were low-acculturated. Hispanic women were more likely to report the ability to access information “all of the time” if they preferred thyroid cancer information in mostly English compared to mostly Spanish (88.5% vs 37.0%, P < 0.001). Low-acculturated (vs high-acculturated) Hispanic women were more likely to have low health literacy (47.2% vs 5.0%, P < 0.001) and report use of in-person support groups (42.0% vs 23.1%, P = 0.006). Depending on their level of acculturation, Hispanic women accessed the internet differently (P < 0.001) such that low-acculturated women were more likely to report use of only a smartphone (34.0% vs 14.3%) or no internet access (26.2% vs 1.4%).

Conclusions

Low-acculturated (vs high-acculturated) Hispanic women with thyroid cancer have greater unmet information needs, emphasizing the importance of patient-focused approaches to providing medical information.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, health literacy, information needs, information seeking behavior, Hispanic women

Thyroid cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in Hispanic women in the United States (1). Despite a favorable prognosis for most patients with thyroid cancer, prior work has found that Hispanic patients with thyroid cancer are more likely to have cancer-related worry and a greater tendency to overestimate their recurrence risk compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts (2, 3). Thus, there may be a role for improving the quality of and access to medical information about thyroid cancer for this understudied patient cohort.

Patients with thyroid cancer have reported significant unmet information needs (4–9). However, it is not clear if patients in the United States who predominantly use a language other than English have greater unmet information needs compared with those whose primary language is English. The majority of studies examining patient-reported receipt of and access to thyroid cancer-related information have primarily focused on patients with internet access who are fluent in written and spoken English (5–8). Thus, the findings may not be generalizable to all Hispanic adults in the United States, a group in which 41% of adults aged 18 and above reported no home internet access, and 31% of adults aged 16 to 65 performed at the lowest proficiency level for English literacy, which corresponds to being able to locate straightforward information in short, simple texts or documents (10, 11).

Little is known about unmet information needs in a Hispanic cohort and how factors such as acculturation and language preference influence access to and use of information resources. Acculturation is the process by which individuals adopt the language, values, attitudes, and behaviors of a different culture (12). Although acculturation is a multidimensional construct, it is profoundly intertwined with the construct of language such that differences in language are associated with differences in social values, views on gender roles and workplace success, and attitudes about government (13, 14). According to studies by the Pew Research Center on language preferences and abilities in adults in the United States, English language-dominant Hispanics had attitudes and beliefs that were more similar to those of non-Hispanic adults than those of Spanish language-dominant Hispanics. This correlation holds even after controlling for factors such as age, gender, education, income, and country of origin (13).

Given the critical role of medical information in cancer patients' treatment decision-making, our goal was to determine access to and utilization of medical information resources by Hispanic women with thyroid cancer in the United States, an understudied patient population. We hypothesized that low-acculturated Hispanic women would have greater unmet information needs when compared with high-acculturated Hispanic women.

Materials and Methods

Data source and study population

Between May 2, 2019, and December 31, 2019, we identified Hispanic women aged 18 to 79 years who had diagnoses of differentiated thyroid cancer reported to the Los Angeles Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2015, and who had previously completed our patient survey on thyroid cancer in 2017–2018 (2, 3). Similar to the methodology used in prior studies on cancer patients, we surveyed female patients who completed our 2017–2018 thyroid cancer survey in Spanish or were identified in the SEER database as having a Spanish surname or being of Hispanic origin (15, 16). The modified Dillman method of survey administration was used to encourage a greater response rate (17). Patients were mailed surveys in both English and Spanish, which were written at an eighth-grade reading level. The initial mailing came with a $20 cash incentive. Bilingual interviewers conducted follow-up calls to nonresponders. Survey data were electronically entered using a double entry method to ensure < 1% error. Survey responses were merged with clinical cancer data from the Los Angeles SEER registry to create a de-identified data set.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan and the University of Southern California, the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, and the California Cancer Registry.

Survey questionnaire design and content

The survey questionnaire was developed based on the research questions and hypotheses, and prior research experience in the thyroid cancer patient population (2, 3, 18, 19). We utilized standard techniques to assess content validity, including the review by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians and survey design experts, and pilot testing in a select cohort of Hispanic patients at the University of Michigan.

Measures

Access to and utilization of medical information resources.

Our cohort of Hispanic women with thyroid cancer were asked about 3 outcome measures of unmet information needs: (1) internet access, (2) thyroid cancer information resources used, and (3) ability to access information.

To evaluate access to digital information resources, patients were asked how they access the internet, with options including: a smartphone, at home on their own computer/tablet, public library, and no internet access. Patients could select more than one option.

Patients were asked about their use of the following resources to find information about thyroid cancer: search engine, medical websites and medical journals, pamphlets/printouts, cellphone or tablet apps, social media, web-based support groups and/or forums, and in-person support groups. Additionally, they were asked to identify their preferred language for the resources used (Spanish/ English for each). For the analysis, patients’ preferred language for thyroid cancer information resources used was dichotomized into “mostly Spanish” and “mostly English.”

Patients were also asked whether they found information in their preferred language while accessing information about thyroid cancer (yes/no). Patients were then asked about the frequency in which they were able to access information in their preferred language with response options based on a 5-point Likert scale from “all of the time” to “none of the time.”

Covariates

We obtained patient-reported highest level of education and income from the patient survey, and age at time of diagnosis (years) from the SEER registry.

We assessed acculturation with the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) (18). Patients were asked to indicate their language preference for the following five items: (1) In general, what language(s) do you read and speak?; (2) What was the language(s) you used as a child?; (3) What language(s) do you usually speak at home?; (4) In which language(s) do you usually think?; and (5) What language(s) do you usually speak with your friends? Response categories were based on a 5-point Likert scale from “only Spanish” to “only English.” A summary score (range 1–5) was calculated by averaging the responses from the individual items. Higher scores indicate a higher level of acculturation. Summary scores of patients who responded to 4 items (N = 8) or all 5 items (N = 263) of the SASH were included in the analysis. Similar to prior publications using the SASH, we used a cutoff of 2.99 to discriminate low-acculturated respondents from high-acculturated respondents (15, 20–22).

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (19, 23, 24). We assessed health literacy with the single-item question “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?” which has been validated using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) and the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA) as the gold standard (19). Response categories were based on a 5-point Likert scale from “extremely confident” to “not at all confident.” Similar to prior publications, low health literacy was defined as “somewhat,” “a little bit,” or “not at all confident” (19, 25).

Statistical analyses

We generated descriptive statistics for all categorical variables. As part of the preliminary analyses to help us understand the relationships among our variables of interest, we performed Rao-Scott adjusted chi-square tests on level of acculturation, highest level of education, and health literacy. The tests showed a significant relationship among the variables (P < 0.001). Since there was collinearity among acculturation, education, and literacy, we only tested for a relationship between acculturation level and unmet information needs. We used Rao-Scott adjusted chi-square tests to test for a relationship between the 3 outcome measures of unmet information needs and acculturation or language preference: (1) internet access and level of acculturation, (2) thyroid cancer information resources used and level of acculturation, and (3) ability to access information and preferred language of resources used.

All statistical analyses incorporated nonresponse weights to reduce potential nonresponse bias. Analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Characteristics of study cohort

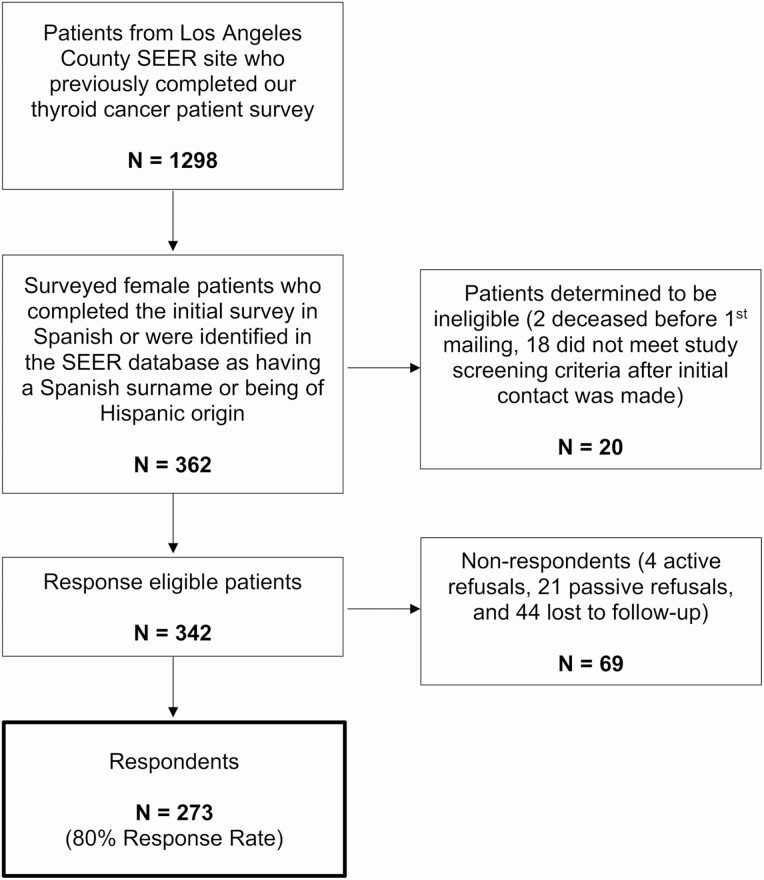

Of the 362 patients identified and mailed a survey, 342 were determined to be eligible. A total of 273 patients responded, yielding an 80% response rate (Fig. 1). Patients’ median age at time of diagnosis was 47 years (range 20–79 years) with 74.6% (N = 203) of Mexican origin, 48.7% (N = 135) with low acculturation, 25.3% (N = 72) with low health literacy, and 14.3% (N = 40) with report of no internet access at home (Table 1). Low-acculturated Hispanic women were more likely to have low health literacy than high-acculturated Hispanic women (47.2% vs 5.0%, P < 0.001). In this cohort, low acculturation was more common in women aged 40–54 years (46.3%) or 55–79 years (38.3%) as compared to 20–39 years (15.4%).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of survey respondents (N = 273, 80% response rate). SEER indicates Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program.

Table 1.

Distribution of patient characteristics (N = 273)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |

| 20–39 | 88 (34.3%) |

| 40–54 | 104 (37.6%) |

| 55–79 | 81 (28.1%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Some college and above | 125 (47.9%) |

| High school diploma and below | 140 (52.1%) |

| Annual household income | |

| > $49 000 | 76 (28.4%) |

| ≤ $49 000 | 121 (43.8%) |

| Missing value | 76 (27.8%) |

| Level of acculturation | |

| High acculturation | 136 (51.3%) |

| Low acculturation | 135 (48.7%) |

| Health literacy | |

| High health literacy | 201 (74.7%) |

| Low health literacy | 72 (25.3%) |

| Internet access at home a | |

| Yes | 227 (85.7%) |

| No | 40 (14.3%) |

a Patients who endorsed internet access at home included those who reported internet access on their own computer/tablet and/or smartphone. Patients who reported no internet access at home included those who reported internet access only at the public library or no internet access.

Patient-reported access to the internet

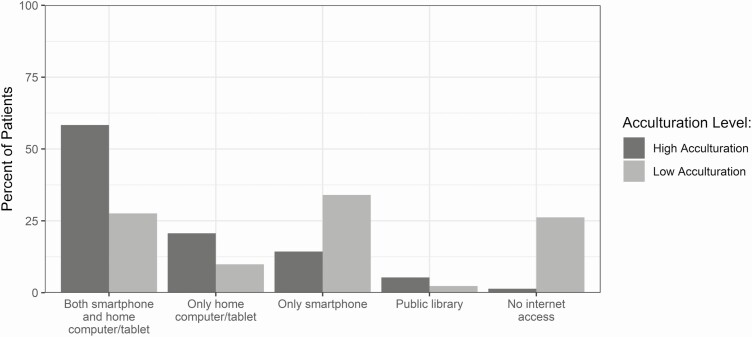

Figure 2 demonstrates that depending on their level of acculturation, Hispanic women accessed the internet differently (P < 0.001). Low-acculturated women were more likely than high-acculturated women to report use of only a smartphone (34.0% vs 14.3%) or report no internet access (26.2% vs 1.4%), and less likely to report use of both a smartphone and home computer/tablet (27.6% vs 58.3%) or report use of only a home computer/tablet (9.9% vs 20.7%). Furthermore, older patients were more likely to report no internet access (30.7% for age 55–79 years vs 13.7% for age 40–54 years and 0% for age 20–39 years) and less likely to report use of both a smartphone and home computer/tablet (27.4% for age 55–79 years vs 37.5% for age 40–54 years and 62.1% for age 20–39 years).

Figure 2.

Patient-reported access to the internet by level of acculturation. Rao-Scott adjusted chi-square P-value was < 0.001.

Patient-reported use of thyroid cancer information resources

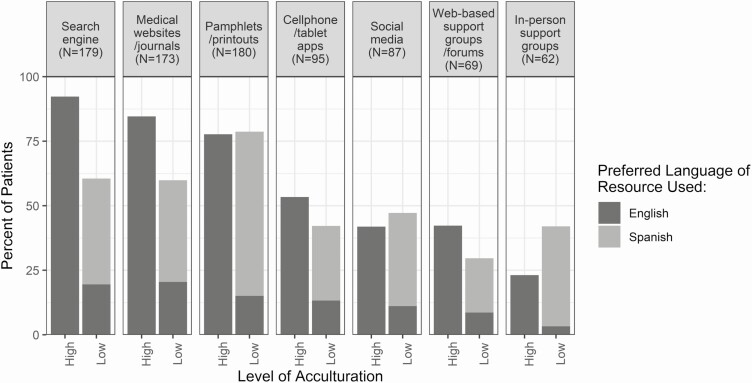

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of resources used by patients to find medical information about thyroid cancer by level of acculturation and preferred language. Low-acculturated Hispanic women reported using thyroid cancer information resources in both English and Spanish, whereas high-acculturated women used resources in English only. Low-acculturated Hispanic women were more likely to report use of in-person support groups (42.0% vs 23.1%, P = 0.006), and less likely to report use of search engines (60.5% vs 92.3%, P < 0.001) and medical websites/journals (59.9% vs 84.6%, P < 0.001) than high-acculturated women. Furthermore, older patients (age 55–79 years vs 40–54 years and 20–39 years) were less likely to report use of search engine, medical websites/journals, social media, and web-based support groups/forums to find information about thyroid cancer (all P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Patient-reported use of thyroid cancer information resources by level of acculturation and preferred language. Low-acculturated (vs high-acculturated) Hispanic women were more likely to report use of in-person support groups (P = 0.006) and less likely to report use of search engines or medical websites/journals (both P < 0.001).

Patient-reported ability to access information in preferred language

Ninety-seven percent of the Hispanic women in our cohort preferred using thyroid cancer information resources in only one language. Patients who were categorized as preferring “mostly English” thyroid cancer information resources included those who preferred only English resources (N = 158) and those who preferred more English than Spanish resources (N = 4). Similarly, patients who were categorized as preferring “mostly Spanish” thyroid cancer information resources included those who preferred only Spanish resources (N = 86) and those who preferred more Spanish than English resources (N = 4).

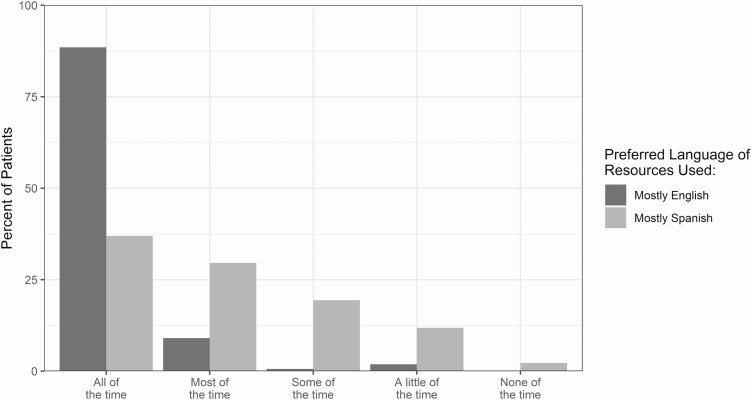

The majority of patients (N = 250) reported being able to access information about thyroid cancer in their preferred language. However, the frequency with which patients could access information in their preferred language differed in those who preferred information in English vs Spanish. Hispanic women were more likely to report the ability to access information “all of the time” if they preferred thyroid cancer information in mostly English compared to if they preferred it in mostly Spanish (88.5% vs 37.0%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Patient-reported ability to access information in preferred language. Hispanic women were more likely to report the ability to access information “all of the time” if they preferred thyroid cancer information in mostly English compared with if they preferred it in mostly Spanish (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Our study provides novel insights into the relationship between acculturation level and unmet information needs in Hispanic women with thyroid cancer in the United States, an understudied patient population. Low-acculturated Hispanic women with thyroid cancer access information differently and have greater unmet information needs compared with high-acculturated Hispanic women.

Our finding that low-acculturated Hispanic women with thyroid cancer were more likely to report no internet access or report use of only a smartphone to access the internet is consistent with prior general studies on internet use in Hispanic adults. According to studies of U.S. adults by the Pew Research Center, Hispanics were more likely to report not using the internet (14%) compared with non-Hispanic Whites (8%) (26). Furthermore, Hispanics who reported not accessing the internet were more likely to be born outside of the United States or in Puerto Rico (77%) and to be more proficient in Spanish than in English (58%) (10). The use of smartphones helps to narrow the internet access gap with 79% of Hispanics reporting that they own a smartphone (vs 82% of non-Hispanic Whites), whereas only 57% own a desktop or laptop computer (vs 82% of non-Hispanic Whites) and 43% own a tablet computer (vs 53% of non-Hispanic Whites) (27). However, 23% of Hispanics (vs 10% of non-Hispanic Whites) do not have broadband at home and access the internet exclusively using a smartphone, which may make it difficult for users to access information due to data caps and small screens (10, 28). While the decision to not subscribe to a high-speed service at home is multifactorial, 59% of nonbroadband adult users cite the high monthly cost as a contributing factor (28).

With the internet, patients have the ability to access American websites and websites of other countries to find thyroid cancer information in English and in Spanish (29–40). In our study, we found that Hispanic women were less likely to report the ability to access information “all of the time” if they preferred thyroid cancer information in Spanish compared to if they preferred it in English. While the drivers of this information access gap remain unknown, it may in part be due to inadequate availability of Spanish resources and/or to patients not knowing how or where to find medical information about thyroid cancer. Although most of the Hispanic women who preferred thyroid cancer information in Spanish reported that they were able to access information at least “some of the time,” little is known about the quality of that information. It is not known if Spanish resources are missing information critical to patients’ treatment decision-making to the same or to a greater extent than that missing from English websites focused on thyroid cancer (41–43).

Even though thyroid cancer is the second most common cancer in Hispanic women in the United States (1), Hispanic women and in particular those who prefer information resources in Spanish, remain an underrepresented patient population in the thyroid cancer literature. Strengths of our study include the focus on this understudied patient population, the administration of the survey instrument in both English and Spanish, a high response rate among surveyed patients, and use of validated survey items to assess acculturation and health literacy. Some potential limitations should be noted. First, patients were not asked specific details on the thyroid cancer information that they accessed or about their satisfaction with this information, which could provide insight into specific gaps in the available Spanish resources on thyroid cancer. Second, although patients reported their current use of information resources, such as a search engine and pamphlets/printouts, we did not specifically ask about preferred media. It is plausible that preferred media varies by age, and understanding this may be key to designing interventions aimed at providing medical information to Hispanic women with thyroid cancer. Third, our cohort was restricted to Hispanic women with thyroid cancer from Los Angeles County where 49% of the population is of Hispanic or Latino origin, and thus compared with health systems with a smaller proportion of Hispanic patients, health systems in the area may more readily have information resources available in Spanish. There may be greater unmet information needs for low-acculturated Hispanic women who live in counties where Hispanics and Latinos account for a smaller percentage of the population. Furthermore, with Spanish being the second most common language in the United States after English (44), there may be greater unmet information needs for thyroid cancer patients who speak and read in another non-English language.

This current study highlights the importance of considering language and resource preferences when providing medical information to this vulnerable but highly relevant patient population. Information on patients’ language and resource preferences may be obtained as part of the patient portal profile or health history questionnaire for new patients, or by medical assistants during the patient assessment at the start of the clinic visit. Patient education handouts on thyroid cancer, developed by the clinic or downloaded from the websites of organizations such as the American Thyroid Association and National Cancer Institute (29–40), can then be provided to patients in their preferred language at the appointment check-in or during the office visit. This would provide physicians with the opportunity to highlight information on the handout that is relevant to topics addressed during the visit, and patients with the opportunity to review the information after the visit. Alternatively, for patients who have internet access, physicians can include reputable websites in the after-visit summary as an information resource for patients to learn more about thyroid cancer. Understanding and addressing unmet information needs is key to improving patient care for all.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with gratitude the patients who responded to our survey.

Financial Support: This study is supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant No. R01 CA201198 with R01 supplement from the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) to Principal Investigator, Dr. Megan Haymart. Dr. Haymart also receives funding from R01 HS024512 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Debbie Chen receives support from grant T32DK007245 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under Cooperative Agreement No. 5NU58DP003862-04/DP003862; and the NCI’s SEER Program under Contract No. HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

- 1. Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, et al. Cancer statistics for hispanics/latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):425-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Papaleontiou M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay BL, et al. Worry in thyroid cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis. Thyroid. 2019;29(8):1080-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen DW, Reyes-Gastelum D, Wallner LP, et al. Disparities in risk perception of thyroid cancer recurrence and death. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1512-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banach R, Bartès B, Farnell K, et al. Results of the thyroid cancer alliance international patient/survivor survey: psychosocial/informational support needs, treatment side effects and international differences in care. Hormones (Athens). 2013;12(3):428-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Husson O, Mols F, Oranje WA, et al. Unmet information needs and impact of cancer in (long-term) thyroid cancer survivors: results of the PROFILES registry. Psychooncology. 2014;23(8):946-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang K, Berthelet E, Grubbs E, et al. Websites, websites everywhere: how thyroid cancer patients use the internet. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(6):1177-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldfarb M, Casillas J. Unmet information and support needs in newly diagnosed thyroid cancer: comparison of adolescents/young adults (AYA) and older patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(3):394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morley S, Goldfarb M. Support needs and survivorship concerns of thyroid cancer patients. Thyroid. 2015;25(6):649-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sawka AM, Brierley JD, Tsang RW, Rotstein L, Ezzat S, Goldstein DP. Unmet information needs of low-risk thyroid cancer survivors. Thyroid. 2016;26(3):474-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown A, López G, Lopez MH.. Digital divide narrows for Latinos as more Spanish speakers and immigrants go online. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Center for Education Statistics. Program for international assessment of adult competencies (PIAAC) results. Available at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/current_results.asp. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 12. Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am Psychol. 2010;65(4):237-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pew Research Center. 2002 National surveys of Latinos. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/dataset/2002-national-survey-of-latinos/. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 14. Lanca M, Alksnis C, Roese NJ, Gardner RC. Effects of language choice on acculturation: a study of Portuguese immigrants in a multicultural setting. J lang Soc. 1994;13(3):315-330. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen DW, Reyes-Gastelum D, Veenstra CM, Hamilton AS, Banerjee M, Haymart MR. Financial hardship among Hispanic women with thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2020. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katz SJ, Wallner LP, Abrahamse PH, et al. Treatment experiences of Latinas after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3022-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM.. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183-205. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dancel LD, Perrin E, Yin SH, et al. The relationship between acculturation and infant feeding styles in a Latino population. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(4):840-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sepucha K, Feibelmann S, Chang Y, Hewitt S, Ziogas A. Measuring the quality of surgical decisions for Latina breast cancer patients. Health Expect. 2015;18(6): 2389-2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Silveira ML, Dye BA, Iafolla TJ, et al. Cultural factors and oral health-related quality of life among dentate adults: Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Ethn Health. 2020;25(3):420-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of america’s adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan S, Parker RM, ed. , ed. Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson M, Perrin A, Jiang J, Kumar M.. 10% of Americans Don’t Use the Internet. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perrin A, Turner E.. Smartphones help Blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anderson M, Horrigan JB.. Smartphones help those without broadband get online, but don’t necessarily bridge the digital divide. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. American Thyroid Association. ATA list of printable/downloadable patient brochures. Available at https://www.thyroid.org/thyroid-information/. February 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30. American Cancer Society. About thyroid cancer. Available at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/thyroid-cancer/about/what-is-thyroid-cancer.html. Accessed. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- 31. National Cancer Institute. Thyroid cancer – patient version. Available at https://www.cancer.gov/types/thyroid. Accessed February 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Thyroid Cancer. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/thyroid/index.htm. Accessed February 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hormone Health Network. Thyroid Cancer. Available at https://www.hormone.org/diseases-and-conditions/thyroid-cancer. Accessed February 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thyroid Cancer Survivors’ Association. Thyroid cancer basics. Available at http://www.thyca.org/download/document/350/TCBasics.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- 35. American Thyroid Association. Lo que necesitas saber sobre la tiroides! Available at https://www.thyroid.org/informacion-sobre-la-tiroides/. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 36. American Cancer Society. ¿Qué es el cáncer de tiroides? Available at https://www.cancer.org/es/cancer/cancer-de-tiroides/acerca/que-es-cancer-de-tiroides.html. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 37. National Cancer Institute. Cáncer de tiroides – versión para pacientes. Available at https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/tipos/tiroides. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cáncer de tiroides. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/spanish/cancer/thyroid/index.htm. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 39. Hormone Health Network. Hoja Informativa: Cáncer de tiroides. Available at https://www.hormone.org/pacientes-y-cuidadores/cancer-de-la-tiroides. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 40. Thyroid Cancer Survivors’ Association. Información en Español. Available at http://www.thyca.org/espanol/. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 41. Air M, Roman SA, Yeo H, et al. Outdated and incomplete: a review of thyroid cancer on the World Wide Web. Thyroid. 2007;17(3):259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Doubleday AR, Novin S, Long KL, Schneider DF, Sippel RS, Pitt SC. Online information for treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer: assessment of timeliness, content, quality, and readability. J Cancer Educ. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01713-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kuenzel U, Monga Sindeu T, Schroth S, Huebner J, Herth N. Evaluation of the quality of online information for patients with rare cancers: thyroid cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(5):960-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. United States Census Bureau. Detailed languages spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009-2013. Available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Accessed February 1, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.