Abstract

Background:

Although family behaviors are known to be important for buffering youth against substance use, research in this area often evaluates a particular type of family interaction and how it shapes adolescents’ behaviors, when it is likely that youth experience the co-occurrence of multiple types of family behaviors that may be protective.

Methods:

The current study (N = 1716, 10th and 12th graders, 55% female) examined associations between protective family context, a latent variable comprised of five different measures of family behaviors, and past 12 months substance use: alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and e-cigarettes.

Results:

A multi-group measurement invariance assessment supported protective family context as a coherent latent construct with partial (metric) measurement invariance among Black, Latinx, and White youth. A multi-group path model indicated that protective family context was significantly associated with less substance use for all youth, but of varying magnitudes across ethnic-racial groups.

Conclusion:

These results emphasize the importance of evaluating psychometric properties of family-relevant latent variables on the basis of group membership in order to draw appropriate inferences on how such family variables relate to substance use among diverse samples.

Keywords: Adolescence, Substance Use, Family Dynamics, Ethnicity

Introduction

Despite improvements in adolescent population health, adolescence is characterized by increases in risk-taking behaviors, and consequently high rates of substance use remain a public health concern.1-3 As investigations of adolescent risk-taking behaviors continue from multiple perspectives, the most protective and promotive influence on youth well-being is the family context.4 Yet, research in this area often evaluates only one quality of the family context at a time, and how it shapes adolescents’ behaviors. It is likely, though, that youth experience multiple types of family behaviors such that their co-occurrence and common variance may be protective.5 Family behaviors such as parental monitoring, involvement, presence, and support, as well as family dinners, may together provide youth with structure and interactions that support less engagement in substance use.

As the U.S. youth population becomes increasingly diverse, proponents continue to emphasize the importance of not using race and ethnicity as control variables in the study of youth outcomes, especially when facets of race and ethnicity may be salient.6,7 There is a myriad of mixed findings regarding ethnic-racial group differences in the relations between protective family behaviors and substance use. One potential way to bring more clarity in interpreting findings from this line of research is to determine whether youth of diverse ethnic-racial backgrounds experience these “protective” family behaviors in similar or different ways. As a step toward characterizing a protective family context, the current study examined whether such family context is experienced similarly among Black, Latinx, and White youth via measurement-invariance assessment. The current study investigated whether multiple types of family behaviors experienced by youth characterize a family context which is protective, its associations with substance use, and to what extent these associations were similar or different among Black, Latinx, and White youth.

Theoretical Framework

Several reviews of protective family behaviors suggest that the family context is a vital source of protection (e.g., positive family relationships) and of risk (e.g., stress, parental substance use, family dysfunction) for adolescent substance use.8-10 In fact, these protective family behaviors are associated with reducing youth risk-taking behaviors above and beyond other factors that contribute to substance use, such as neighborhood, schools, and peers.4,11

Family system theory may elucidate how the family context provides a critical platform for meaningful interpersonal interactions that shape youths’ behaviors.9 Family system theory posits that a system of individuals (i.e., the family) is a vital organizing agent for development, whereby an individual who feels bonded to this system is more likely to adhere to the norms, rules and regulations established by that system.9 The current study views the family context as a system where youth may experience behaviors and expectations that reflect a set of family norms, rules, regulations, and supports that confer protection.

Parental monitoring, parental involvement, family dinners, parental presence, and positive parent-child relationships are types of related, yet distinct, family behaviors that have been identified in prior research as protective against youth substance use.8-10,12 Studies have demonstrated the unique contribution of specific family behaviors on substance use in the context of other protective family behaviors, as well as the interactive effects of two types of family behaviors (e.g., parental monitoring and support) on substance use.13-15 In addition, studies have demonstrated that many of these family behaviors tend to be correlated with one another.16,17 However, less is known about whether the co-occurrence of these protective family behaviors have meaningful implication for youth substance use.5 Multiple types of family behaviors may better reflect youths’ day-to-day experience of their family context than focusing on any specific type of family behavior. Specifically, the common variance among multiple family behaviors may present youth with a structure that supports their well-being. Additionally, measuring the family context as a latent construct in a Structural Equation Modeling framework accommodates measurement error whereas using all family measures as covariate would ignore measurement error.

Family Context and Risk Involvement

Parental monitoring refers to the degree to which adolescents believe their parents are aware of their whereabouts,18 and has been associated with less alcohol and marijuana exposure.19-21 Parental involvement refers to the degree to which adolescents perceive that their parent is engaged in their daily activities.22 Examples may include parents’ encouragement to complete chores or homework. Parental presence, another hypothesized protective family behavior, refers to how often parents are home when their adolescent is home. It is important to note that while parental involvement in the daily activities of their child may implicate parental presence at home, presence does not necessarily equate to involvement. Parental presence at home may structure a child’s environment, yet given the autonomy which emerges during adolescence, it is important to specifically measure the degree of parental involvement. Altogether, parents’ involvement in their child’s activities and their presence at home has been shown to buffer youth from substance use.19,22

Frequent family dinners are also considered as another protective factor for youth as it has been associated with less substance use and positively associated with other protective family behaviors, such as family connectedness, parental monitoring, and parent-child communication.14,16,17,23 Supportive presence reflects an adolescent’s perceived interaction with parents and the extent to which they feel they can communicate with parents about what is going on in their lives.8 Similar to the other family behaviors discussed above, supportive presence has been associated with less substance use.24-26 These family behaviors are prevlant across multiple studies assessing their role in reducing substance use in youth. These behaviors potentially provide youth with structure and interpersonal interactions that could support a protective family context. As discussed below, however, some of these family behaviors have presented unique protective influence for particular ethnic-racial groups and therefore require additional consideration.

Evaluating a Protective Family Context across Race and Ethnicity

In operationalizing a protective family context, it is important to consider how ethnic-racial background, as a facet of development, may influence how family behaviors are experienced across racially and ethnically diverse youth.27-29 Beyond how these family behaviors may be differentially experienced, much empirical evidence has suggested variability in substance exposure as well as in the buffering effects of family behaviors among racially and ethnically diverse youth. The family behaviors discussed above have all been demonstrated to be protective against health risk behaviors across multiple ethnic-racial groups.19,21,30,31 Yet, some family behaviors, such as parental support, have been shown to be particularly more protective for certain ethnic-racial groups such as Latinx youth.32 Research on ethnic-racial differences in substance use and initiation have yielded mixed results, with some research indicating ethnic-racial differences.33,34 Other research, however, has indicated no ethnic-racial differences in adolescent substance use.31,35

There is limited and mixed evidence regarding for whom, and how, these family behaviors confer protection against substance use among racially and ethnically diverse adolescents. Some research indicates that parental behaviors, specifically parental support and family acceptance, seem more important for Latinx adolescents than their Black or White counterparts.32,34 Differential parenting effects are also evident in other types of parenting behaviors among Black, Latinx, and White adolescents. For example, an authoritarian parenting style can decrease the proportion of heavy episodic drinking in Black adolescents while the same parenting style does not provide a protective factor for White adolescents;36 greater parental respect can protect against substance use in White adolescents.37 Ideally, differential protective effects may have the most informative value when these family behavior measures have similar psychometric properties across diverse youth. However, despite that, many of these family behaviors measures have been developed and validated for either White youth samples or nationally representative diverse samples, psychometric evaluations like measurement invariance have been previously overlooked. In evaluating the characteristics of a protective family context, it is essential to determine whether a constellation of widely used parenting measures manifest similar measurement properties across diverse ethnic-racial groups. A measurement invariance assessment, for example, may demonstrate the existence of a protective family context latent construct for multiple ethnic-racial groups and identify whether any particular family indicator differs in its contributions in a particular ethnic-racial group compared to others.

Current Study

Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of parental monitoring, parental involvement, parental presence, family dinners, and parental support have all been shown to reduce youth health risk behaviors. However, this set of family behaviors likely co-occur and there is evidence suggesting that these family behaviors are related to each other.16,17 It is unknown whether the common variance among these family behaviors has meaningful implications for youth substance exposure.5,16,17 In operationalizing a protective family context latent construct, we examined whether this family context was experienced similarly by different ethnic-racial groups via an evaluation of measurement invariance (e.g., factor structure and factor loading equivalence). This measurement invariance assessment provides the opportunity to examine the relationship between protective family context and substance use in the past 12 months among Black, Latinx and White youth, as well as the extent to which these associations were similar or different among three ethnic-racial groups.

Methods

Participants

Data were drawn from a study characterizing adolescent health risk behavior among 10th and 12th graders (N = 2017) recruited from public schools using a quota sampling design to approximate the diversity of the statewide population. From the larger study sample, 1716 adolescents (age M = 16.7, SD = 1.1; 49% 10th grade; 55% females) were included in the present analysis, comprised of 1103 White Non-Hispanic adolescents (White youth), 453 Black Non-Hispanic adolescents (Black youth), and 161 Latinx/Hispanic adolescents (Latinx youth). The rest of the participants identified as belonging to ethnic-racial groups that were too small in size for the present analysis, in particular measurement invariance testing, and thus were excluded (n = 301).

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the University [blinded] Institutional Review Board. Active parental consent and adolescent assent for participation were obtained. Among 5009 potentially eligible participants (contacted by mail through their schools), 2278 (45.5%) of students provided parental consent by returning consent forms to their schools, and 2017 (88.5%) of those with parental consent participated, with absence from school on the day of data collection as the primary reason for non-participation. Data were collected between mid-March 2015 and mid-February 2016. Data were collected in schools during school hours or after school via a self-report survey, which was administered using computer-assisted interviewing (Illume: 5.1.1.18300). Upon completion of the survey, participants were compensated with $50 for their time.

Measures

Parental monitoring.

Three items measured parental monitoring. The scale had similar reliability (α = .84) with that of a national sample (α =.85-86).38 Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. A mean score was calculated such that higher means indicate more parental monitoring. A sample item includes, “My parents know where I am after school.”

Parental involvement.

Four items measured parental involvement. The scale had similar reliability (α = .58) with that of a national sample (α = .54).22 Items were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1 = never to 4 = often. A mean score was calculated such that higher scores indicate more parental involvement. A sample item includes, “How often do your parents check on whether you have done your homework?”

Parental presence.

Six items measured parental presence and this scale has been utilized in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.39,40 Three items assessed maternal presence and three items assessed paternal presence. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. A total score was calculated such that higher scores indicate more parental presence in the home. A sample item includes, “How often is she [mother] home when you return from school?”

Family dinner.

One item assessed the number of times spent eating dinner with one’s family, “During a typical week, how often do you have dinner with one or both of your parents?” This item was rated on a 6-point scale: 1 = less than one day per week, 2 = one day, 3 = two days, 4 = three days, 5 = four or five days, 6 = six or seven days.

Supportive presence.

One item measured parental support, “If you were having problems in your life, do you think you would talk them over with one or both of your parents?” This item was rated on a 3-point scale: 0 = No, 1 = Yes, for at least some of my problems, 2 = Yes, for most or all of my problems.

Substance use.

One item was used to assess the frequency of exposure to each type of substance: alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and e-cigarettes/vaporizers. An example item includes, “On how many occasions (if any) have you used an electronic vaporizer such as an e-cigarette during the last 12 months?” Items were rated on a Likert-type scale and response options include: 1 = zero occasions, 2 = one to two occasions, 3 = three to five occasions, 4 = six to nine occasions, 5 = ten to 19 occasions, 6 = twenty to 39 occasions, 7 = forty or more. Items are identical to those used in the annual, national Monitoring the Future surveys.2

Analysis Plan

Mplus 8.141 was used to conduct a multi-group measurement invariance assessment and a multi-group path model to test the association between the latent protective family context construct and four substance use measures (alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and e-cigarette). The latent construct, protective family context, comprised of mean score or total score derive from each family measure. Using the summary scores of these particular family measures as factor indicators was chosen to preserve model parsimony of a multi-group path model (i.e., three groups) with four dependent measures each (alcohol, marijuana, cigarette, and e-cigarette). Family behavior summary scores has been previously used in a Structural Equation Modeling Framework (e.g., Maslowsky25)

Measurement invariance analyses assessed whether the latent variable had equivalent psychometric properties across three ethnic-racial groups. This step was important in order to assess the relationships between protective family context and substances use across race/ethnicity in the multigroup path model. Configural invariance indicates equivalence in factor structure. Metric invariance indicates equivalence in factor loadings. Scalar invariance indicates equivalence in item intercepts.42 Chi-square difference tests between invariance models indicated whether model fit was compromised as features of the model (e.g., factor loadings) are constrained from configural to metric, and from metric to scalar. Configural and metric invariance were deemed appropriate to test the association between the latent variable and the outcomes of interest in the proceeding multi-group path model.42 Scalar invariance would be necessary to compare the mean of the latent variable across groups, which was not an aim of the present analysis. In the case of measurement non-invariance, modification indices would be extracted to specify a partial metric measurement invariance model.

Protective family context was defined as latent variable based on the specifications of the measurement invariance assessment and was entered into the multi-group path model to examine the associations between protective family context and each of the four types of substance exposure. To account for missingness, we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML). The multi-group model controlled for sex (0 = female; 1 = male), parental level of education (1 = completed grade school or less, 6 = graduate or professional school after college), and grade (0 = 10th grade, 1 = 12th grade). We followed recommended thresholds including a comparative fit index (CFI) of greater than .90, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of less than .05 with a 90% confidence interval less than .08, and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of less than .08.43,44 First, a multi-group path base model was estimated where the latent variable was specified based on the measurement invariance assessment described above; and second, the association between the latent variable and the outcomes was freely estimated across groups (see supplemental Figure S1).

To test whether the associations between protective family context and substance use were different across groups, the multi-group path base model was compared, via a Chi-square difference test, to a nested constrained path model in which all paths (protective family context to substance use) were constrained as equal across groups. A non-significant Chi-square difference test would indicate that the equality constraints were tenable, therefore path estimates are similar across groups. A significant Chi-square difference test would indicate that the equality constraints were not tenable and that the paths estimates are not similar across groups.

To determine which group differed in their path estimate, the multi-group path base model would be sequentially constrained. A nested constrained model involved freely estimating a path (i.e., protective family context to cigarette use) in one group and constraining the same path as equal in the two other groups. This nested constrained model would be compared to the unconstrained model where a non-significant Chi-square difference test suggests that constrain path is not different between two groups and could be held equal. If the equality constraints not tenable (e.g., significant Chi-square difference), then a subsequent set of constraints were applied that involved freely estimating the path of interest for another group and constraining the path as equal for the remaining two groups. If no equality constraints for a path of interest are tenable, meaning the path could be held equal between any two groups, this would suggest that the path estimate is significantly different among each of the groups and should be freely estimated.

Results

Preliminary Results

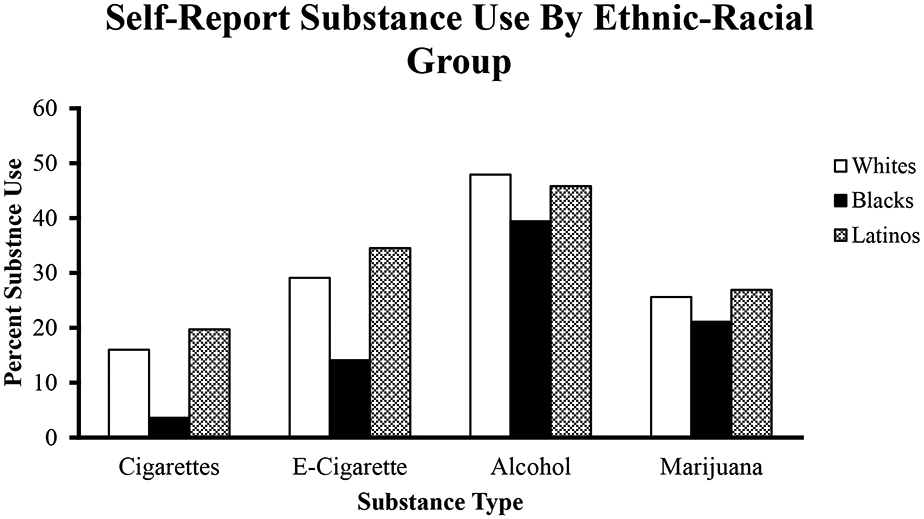

Fifty-five percent of adolescents reported engaging in some kind of substance use. Among participants who did report use, about 50% engaged in alcohol use, 12% in cigarette use, 19% in marijuana use, and 21% in e-cigarette/vaporizer use. Percentages of substance use by ethnic-racial group are provide in Figure 1. Black youth had a lower percentage of substance use overall compared to White and Latinx youth. All three ethnic-racial groups reported higher percentages of alcohol use and lower percentages of cigarette use compared to other types of substance use. Correlations between each family measure, as well as their correlation with each type of substance use, are presented by ethnic-racial group in Tables 1-3. Among Black youth, all family measures were positively associated with each other except for parental presence and parental monitoring. Among Latinx youth, all family measures were positively associated with each other except for parental presence and supportive presence. Among White youth, all family measures were positively associated with each other. The magnitude of the correlations between family measures and each substance use varies across ethnic-racial group. For example, family dinners had moderate negative associations with each type of substance use among Latinx youth, while demonstrating no association with any type of substance use among Black youth. Among each ethnic-racial group, parental monitoring was the only family measure that is negatively and overall strongly associated with all of the four types of substance use.

Figure 1.

Percentages of self-reported substance use past 12 months by ethnic-racial group.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for primary study variables for Black youth (n=453)

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.) Family Dinners | 3.7 (2.0) | - | ||||

| 2.) Parental Involvement | 2.8 (0.7) | .38*** | - | |||

| 3.) Parental Monitoring | 4.5 (0.7) | .17*** | .28*** | - | ||

| 4.) Parental Presence | 7.4 (4.5) | .21*** | .14** | .07 | - | |

| 5.) Supportive Presence | 1.0 (0.7) | .34*** | .31*** | .17*** | .11* | - |

| Past 12-months Substance Use | ||||||

| Alcohol | −.04 | −.15** | −.21*** | −.06 | −.02 | |

| Cigarette | −.07 | −.13* | −.28*** | .02 | −.03 | |

| Marijuana | −.05 | −.05 | −.36*** | −.00 | −.01 | |

| Vaporizer/E-Cigarette | −.00 | −.15* | −.21*** | −.00 | −.04 | |

Notes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for primary study variables for White youth (n=1103)

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.) Family Dinners | 4.4 (1.6) | - | ||||

| 2.) Parental Involvement | 2.8 (0.7) | .39*** | - | |||

| 3.) Parental Monitoring | 4.4 (0.7) | .31*** | .32*** | - | ||

| 4.) Parental Presence | 9.6 (3.6) | .23*** | .28*** | .25*** | - | |

| 5.) Supportive Presence | 1.1 (0.7) | .26*** | .30*** | .27*** | .18*** | - |

| Past 12-months Substance Use | ||||||

| Alcohol | −.17*** | −.20*** | −.40*** | −.12*** | −.06 | |

| Cigarette | −.13*** | −.18*** | −.20*** | −.18** | −.09** | |

| Marijuana | −.21*** | −.23*** | −.35*** | −.11*** | −.11*** | |

| Vaporizer/E-Cigarette | −.10** | −.15*** | −.25*** | −.11*** | −.10** | |

Notes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Primary Results

Measurement invariance assessment indicated the latent variable showed configural invariance with five indicators as a single variable across race/ethnicity. Compared to a nested model with constrained factor loadings (configural vs metric), the model fit was significantly compromised (see Table 4). Modification indices suggested parental monitoring was variant at the metric level for Black youth. Upon freely estimating the parental monitoring factor loading for Black youth and constraining all other factors loading equal across ethnic-racial groups, partial (metric) measurement invariance was supported (see Table 4). All factor loadings were significant at p < .001(see Figure 2).

Table 4.

Multi-Group Measurement Invariance Assessment

| Model | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

χ2(df), p-value | Model Comparison |

Δχ2(df),p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1: Configural | .997 | .993 | .02 (.00, .05) | 18.140 (15), .255 | - | - |

| M2: Metric | .985 | .980 | .03 (.01, .05) | 37.432 (23), .030 | M1 vs M2 | 19.292 (8), .013 |

| M3: Partial Metric | .993 | .990 | .02 (.00, .04) | 29.022 (22), .144 | M1 vs M3 | 10.882 (2), .144 |

Notes. Groups = Black, Latinx, White. M3 partial metric model, all factor loadings across groups were constrain as equal except for parental monitoring for Black youth. The factor loading for parental monitoring among Black youth were freely estimated in all subsequent models.

Figure 2.

Multi-group path model. The effect of protective family context on alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and e-cigarette/ vaporizers exposure in the past 12 months. Model fit: χ2(110) = 398.443, p < .001; CFI =.905; TLI = .837; RMSEA =. 070, 90 % CI =.06, .08; SRMR = .057. Covariates include gender, parent education, and grade, and were regressed on protective family context and each type of substance use. Model depicts unstandardized coefficients and standard error. Parental monitoring factor loading freely estimated for Black youth (italicized) and constrained as equal for Latinx and White youth (bold). All other factor loadings held equal across groups. Paths freely estimated for Black youth (italicized) and constraint as equal for Latinx and White youth (bold).

Note. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

The primary analysis examined the relationships between the latent construct of protective family context and each of the four substances in a multi-group model. The covariates were modeled onto protective family context and each of the four types of substance use for each group. Based on path coefficient estimates in the multi-group path base model (Figure S1), estimates for Black youth were of relatively less magnitude compared to Latinx and White youth. To test for group differences in path estimates, the procedure for sequentially constraining paths began with freely estimating the path of interest for Black youth and constraining the same path as equal among White and Latinx youth. Supplemental Table S1 details procedures for comparing nested sequentially constrained models starting from the base model. The final model is depicted in Figure 2.

In the final multi-group path model, protective family context was associated with less cigarette, e-cigarette/vaporizer, alcohol, and marijuana use in the past 12 months among Latinx and White youth. These associations did not differ significantly among Latinx and White youth and were thus allowed to be constrain as equal. Among Black youth, protective family context was associated with less cigarette and e-cigarette/vaporizer use, however to a lesser extent compared to Latinx and White youth (see Figure 2). There were different patterns of association between the covariates and past 12 months substance use for each ethnic-racial group (Table 5). Notably, there were sex differences in alcohol and marijuana use among Black youth, in alcohol use among Latinx youth, and in e-cigarette/vaporizer use among White youth. Among White youth, higher parental education was associated with more alcohol and less cigarette use. Among Black and White youth, 12th graders engaged in more alcohol and marijuana use than 10th graders. Parental education was positively associated with protective family context, and grade was negatively associated with protective family context, each of similar magnitude among each ethnic-racial group.

Table 5.

Multi-Group Path Model Covariates

| Protective Family Context |

Cigarettes | E-Cigarettes/ Vaporizers |

Alcohol | Marijuana | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | |||||

| Male (Reference =Female) | −.03 (.06) | .06 (.06) | .07 (.06) | −.11 (.06) * | .12 (.06) * |

| Parent Education | .22 (.06) *** | .07 (.06) | .02 (.06) | −.07 (.06) | −.04 (.06) |

| 12th Grade (Reference = 10th Grade) | −.26 (.06) *** | .09 (.06) | −.02 (.06) | .29 (.06) *** | .29 (.06) *** |

| Latinx | |||||

| Male (Reference = Female) | −.02 (.09) | −.06 (.09) | .05 (.09) | −.23 (.08) ** | −05 (.09) |

| Parent Education | .19 (.09) * | −.03 (.09) | −.02 (.09) | −.03 (.08) | .08 (.09) |

| 12th Grade (Reference = 10th Grade) | −.23 (.09) * | −.06 (.09) | .02 (.09) | .11 (.09) | .15 (.08) |

| White | |||||

| Male (Reference = Female) | −.00 (.04) | −.06 (.03) | .09 (.03) ** | −.02 (.03) | .04 (.03) |

| Parent Education | .25 (.04) *** | −.14 (.03) *** | −.03 (.03) | .09 (.03) ** | −.02 (.03) |

| 12th Grade (Reference = 10th Grade) | −.22 (.04) *** | .03 (.03) | .02 (.03) | .22 (.03) *** | .07 (.03) * |

Notes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. Standard coefficient (standard error). Covariates corresponds the Multi-Group Path Model in Figure 2.

Discussion

The family context is vital for children’s development and has been considered as a source of both protection and risk for adolescent substance use. It is no surprise that the family context remains a key platform for many interventions to promote positive youth health behaviors. The present study found that an overarching family context characterized by multiple types of family behaviors and this family context was associated with less adolescent substance use. Through measurement invariance assessment, protective family context was evident among Black, Latinx, and White youth in partially similar ways comprised of family dinners, parental involvement, parental monitoring, parental presence, and parental support. This yielded a comparable way to interpret the relations between protective family context and various types of substance use across three ethnic-racial groups. Overall, protective family context was experienced similarly among Latinx and White youth and was associated with less adolescent alcohol, cigarette, e-cigarette, and marijuana use. Black youths’ parental monitoring experiences contributed to their protective family context in distinct ways compared to Latinx and White youth. Black youth also benefited from a protective family context (as a latent construct), however only with regards to cigarette and e-cigarette exposure, and to a lesser extent compared to Latinx and White youth. It is important to note, however, that overall rates of substance use were lower among Black youth in general (Figure 1), and that parental monitoring as an independent variable was significantly correlated with lower substance use across all categories (Table 1).

Protective family context

Drawing from family systems theory, evaluating the co-occurrence of multiple family behaviors may capture how youth experience their family environments more so than focusing on any one type of family behavior. A contextually informative picture of youths’ family environment may help to better understand its influence on youth behaviors. Although these family behaviors are inherently interpersonal among family members, adolescents’ own perceptions of these family experiences, rather than parents, are most informative regarding adolescents’ health risk-behavior involvement.20,45 These behaviors likely represent parents’ daily involvement in the lives of their adolescents, which help to structure adolescent behaviors. Consistently engaging and adhering to the expectations set by a family system may influence how youth regulate their behaviors and make decisions in multiple domains. However, given ethnic-racial differences in how family behaviors serve as protective factors against substance exposure and the inherent contextual role race and ethnicity plays in everyday family interaction, it is important to consider how variant this protective family context is across race and ethnicity.28,29,46 The present student examined whether protective family context was supported by multiple family indicators among Black, Latinx, and White youth.

Measurement invariance assessment of the latent protective family context construct across Black, Latinx, and White youth suggested it had similar factor structure (configural invariance) but differing factor loadings (metric non-invariance) across groups. Metric non-invariance was identified with the parental monitoring indicator among Black youth. The factor loading of parental monitoring was freely estimated among Black youth and all other indicators were allowed to be constrained as equal-- achieving a partial metric invariance model of the protective family context variable. Metric invariance was deemed acceptable for the subsequent path analysis as it allows to assess factor covariances across group.42

The variability in the factor loadings of parental monitoring among Black youth merits further discussion. Overall, compared to Latinx and White youth, parental monitoring had weaker correlations among family variables among Black youth (Table 1-3). This is not to say that parental monitoring is not protective among Black youth, as the correlations in Table 1 indicate. The present study also finds comparable rates of reported parental monitoring across groups (Table 1-3). Prior research has shown the importance of parental monitoring among Black youth, and interestingly, lower rates of parental monitoring among Black youth compared to White youth.47-49 In the context of multiple type of family behaviors, however, the importance of parental monitoring is reflected in its significance as an indicator of protective family context among Black youth, while the nature of its contribution to a protective family context is different compared to Latinx and White youth. Altogether, the lesser, yet significant, contribution of parental monitoring in a protective family context among Black youth compared to Latinx and White youth has implications for interpreting the relations between protective family context and substance use. Estimated effects (e.g., betas) are comparable across race and ethnicity as long as it is acknowledged that the contribution of parental monitoring to protective family context was freely estimated for Black youth while the contribution of parental monitoring to protective family context occurred in similar ways among Latinx and White youth. For example, when interpreting the negative association between protective family context and cigarette use in the Black youth group (Figure 1), the contribution of parent monitoring is significant in supporting this protective family context -but of a lesser extent compared to Latinx and White youth.

Protective family context and substance use

In general, about 55.3% of adolescents reported engaging in some form of substance use in the past 12 months. Alcohol was the most prevalent substance, mirroring the high prevalence among 12 graders around the same year, 2015, in the national Monitoring Future study.2 Interestingly, the use of e-cigarettes/vaporizer surpassed the use of cigarettes, which was the least prevalent. This pattern is consistent with the trends in e-cigarettes/vaporizer use found by the national Monitoring the Future study.2,50,51 Efforts to improve adolescent health should continue to focus on alcohol and should also elevate the consideration of vaporizer use and its potential health effects.50

In the final multi-group path model, there were demographic difference in substance use within each ethnic-racial group (see Table 5). Black females engaged in more alcohol use and less marijuana use than Black males. Similarly, among Latinx youth, females engaged in more alcohol use than male. Among White youth, males engaged in more e-cigarettes/vaporizer use than males. These patterns are consistent with general gender difference reported in national survey findings.51 Variation in substance use with respect to parent’s education level only emerged among White youth whereby higher parent education level was associated with less cigarette and more alcohol use. Finally, Black and White 12th graders engaged in more alcohol and marijuana use compared to 10th graders, a pattern that is also consistent with previous national survey findings.51

Protective family context was associated with less substance use in the past 12 months, but this association varied according to the type of substance use across groups. The extent to which protective family context was negatively associated with cigarette and e-cigarettes/vaporizer did not differ among Latinx and White youth and was of a lesser magnitude among Black youth. Protective family context was associated with less alcohol and marijuana use among Latinx and White youth to a similar extent. This association was not supported among Black youth.

The present findings illustrate that more detailed psychometric evaluation of family behaviors may help discern its protective role among diverse youth. Continued evaluations (e.g., scalar and residual invariance assessments) of derived family-latent variables, such as protective family context, may have the potential to identify specific family behaviors of protective value for diverse youth. The group specific findings of the present study may have been overlooked had protective family context been defined in an aggregated group of ethnic-racially diverse youth with race/ethnicity specified as control variables. A multi-group approach allowed to model the association between protective family context and substance use in a way that accounted for ethnic-racial variability in the protective family context variable. In practice, promoting a protective family context should perhaps involve increasing multiple types of family behaviors that serve to structure adolescent development. Since it is possible that different ethnic-racial group could have different important indicator of a protective family context, similar psychometric evaluations in the present study could be a way of identifying such salient family behaviors that may confer unique protection.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although protective family context was evident similarly among three ethnic-racial groups, this still may not fully reflect the ways in which these behaviors are experienced on a daily basis. For example, psychometrically, family dinners and extent of parental involvement may be interpreted similarly for diverse youth in the U.S. However, what that family time looks like or how parents’ involvement is experienced may vary qualitatively but not quantitatively (at least as captured in these scales) due to ecological factors that were not evaluated as covariates in this study (e.g., social economic status, employment, neighborhood safety, culture). Recent ecological models of development place culture at the forefront, rather than as a distal informer of development, such that culture is an organizing agent of daily interaction within the family context.52 Future research needs to look beyond ethnic-racial group differences and take into account how specific cultural values and practices may influence the promotion of positive youth health behaviors.53 Relatedly, there may be social culturation variations in the perception and socialization of substance use and substance use risks across ethnic-racial groups that may impact reasons for engaging or avoiding substance use.55

Based on evidence from previous studies, parental support was expected to contribute non-invariance among Latinx youth based on the saliency of this type of family interaction and its unique protective effect against substance use.19,21,32 One reason for not supporting this may be in how parental support was assessed in the present study compared to other studies with more items and wider response options. Further measurement invariance assessment at the scalar (indicator intercepts) and residuals levels would help to determine whether a given level of protective family context is experienced in the exact way among diverse youth (e.g. comparison of the latent means). In addition, although the relatively smaller Latinx sample was sufficient in size for measurement invariance assessment, a larger sample of comparable size to the Black and White youth group could help ensure a similar range in variability in Latinx youth family behaviors and substance use experience.

Further research should consider alternative measures of the family indicators studied here as well other family behaviors that were not accounted for in the present study. Future research may also benefit from testing whether certain interactive effects between two or more family behaviors provide unique protection than any single one type of family behavior. Assessing the covariance among multiple family behaviors is one way to examine the family context. A person-centered approach such as profile clustering may be another way to operationalize the family context. Assessing family behaviors individually ultimately still provides meaningful implications about the effectiveness of a particular behavior in buffering adolescent substance use. There is substantial potential to determine whether such latent family context variables also vary by other salient demographic and identity-base variables such as gender and social economic status. Finally, as parents and adolescents renegotiate expectations of one another, it is important to consider how protective the family context remains over the adolescent years.55 The current study examined a non-clinical sample, and future research may benefit from examining a protective family context in clinical samples or heavier substance users.

Conclusion

The family context is a meaningful environment for adolescent development and is a key platform for intervention and prevention. We infer that protective family context reflects a system of family behaviors, whereby youth consistently regulate their behaviors to align with expectations set through experiences of protective family behaviors. The current study showed that the covariance among multiple family behaviors together provide a protective context that buffers engagement in substance use among youth from diverse ethnic-racial backgrounds. The benefits of using a multi-group approach was evident in how it allowed the identification of the ways in which protective family context varied across race-ethnicity, as well as how its relations with a myriad types of substance use varied across race-ethnicity.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for primary study variables for Latinx youth (n=161)

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.) Family Dinners | 4.2 (1.8) | - | ||||

| 2.) Parental Involvement | 2.7 (0.7) | .37*** | - | |||

| 3.) Parental Monitoring | 4.3 (0.9) | .30*** | .40*** | - | ||

| 4.) Parental Presence | 7.9 (4.4) | .18* | .23** | .26*** | - | |

| 5.) Supportive Presence | 1.1 (0.7) | .30*** | .50*** | .38*** | .13 | - |

| Past 12-months Substance Use | ||||||

| Alcohol | −.20* | −.22* | −.28** | −.10 | −.30*** | |

| Cigarette | −.28** | −.09 | −.30*** | −.22* | −.18 | |

| Marijuana | −.25** | −.17 | −.45*** | −.02 | −.26* | |

| Vaporizer/E-Cigarette | −.28** | −.20* | −.35*** | −.04 | −.30*** | |

Notes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Acknowledgements:

This research was, in part, supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) grant R01 HD075806-01A1 (D.P. Keating, Principal Investigator). The authors thank Peter Batra, Meredith House, Kyle Kwaiser, Kathleen LaDronka, and Rebecca Loomis and the U-M Survey Research Operations staff for their generous support. Portions of these data were presented at the 2017 Society for Research in Child Development biennial meeting (Austin, TX).

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Driscoll AK, Mathews TJ. Births: Final Data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2017;66(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future, National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2015. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shults RA, Williams AF. Trends in teen driver licensure, driving patterns and crash involvement in the United States, 2006-2015. Journal of Safety Research. 2017;62:181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wen M Social Capital and Adolescent Substance Use: The Role of Family, School, and Neighborhood Contexts. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2017;27(2):362–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas HJ, Kelly AB. Parent-child relationship quality and adolescent alcohol use. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;47(11):1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng TL, Goodman E. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in research on child health. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e225–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychological Association ATFoRaEGiP. Race and Ethnicity Guidelines in Psychology: Promoting Responsiveness and Equity. In. http://www.apa.org/about/policy/race-and-ethnicity-in-psychology.pdf2019.

- 8.Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44(9):774–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vakalahi HF. Adolescent substance use and family-based risk and protective factors: a literature review. Journal of Drug Education. 2001;31(1):29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velleman, Templeton, Copello. The role of the family in preventing and intervening with substance use and misuse: a comprehensive review of family interventions, with a focus on young people. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24(2):93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerman GM, Farrell C. Parents, Peers, Perceived Risk of Harm, and the Neighborhood: Contextualizing Key Influences on Adolescent Substance Use. J Youth Adolescence. 2017;46(1):228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bry BH, Catalano RF, Kumpfer KL, Lochman JE, Szapocznik J. Scientific findings from family prevention intervention research. Drug Abuse Prevention Through Family Interventions. 1998:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippold MA, Greenberg MT, Graham JW, Feinberg ME. Unpacking the Effect of Parental Monitoring on Early Adolescent Problem Behavior: Mediation by Parental Knowledge and Moderation by Parent-Youth Warmth. Journal of family issues. 2014;35(13):1800–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen B The relationship between frequency of family dinner and adolescent problem behaviors after adjusting for other family characteristics. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(1):187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfarb S, Tarver WL, Sen B. Family structure and risk behaviors: the role of the family meal in assessing likelihood of adolescent risk behaviors. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2014;7:53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Utter J, Denny S, Robinson E, Fleming T, Ameratunga S, Grant S. Family meals and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2013;49(11):906–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulkerson JA, Story M, Mellin A, Leffert N, Neumark-Sztainer D, French SA. Family dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: relationships with developmental assets and high-risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(3):337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(3):366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagan Rivera M, Depaulo D. The role of family support and parental monitoring as mediators in Mexican American adolescent drinking. Substance Use and Misuse. 2013;48(14):1577–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cottrell L, Li XM, Harris C, et al. Parent and Adolescent Perceptions of Parental Monitoring and Adolescent Risk Involvement. Parent-Sci Pract. 2003;3(3):179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopak AM, Chen AC, Haas SA, Gillmore MR. The importance of family factors to protect against substance use related problems among Mexican heritage and White youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124(1-2):34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilgrim CC, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Mediators and Moderators of Parental Involvement on Substance Use: A National Study of Adolescents. Prevention Science. 2006;7(1):75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fruh SM, Fulkerson JA, Mulekar MS, Kendrick LAJ, Clanton C. The Surprising Benefits of the Family Meal. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2011;7(1):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C-T, Padilla-Walker LM, Memmott-Elison MK. The role of parents and peers on adolescents’ prosocial behavior and substance use. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2017;34(7):1053–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maslowsky J, Schulenberg J, Chiodo LM, et al. Parental Support, Mental Health, and Alcohol and Marijuana Use in National and High-Risk African-American Adolescent Samples. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2015;9(Suppl 1):11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly AB, Toumbourou JW, O'Flaherty M, et al. Family relationship quality and early alcohol use: evidence for gender-specific risk processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(3):399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blum RW, Beuhring T, Shew ML, Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Resnick MD. The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(12):1879–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coll CG, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Philadelphia, PA, US: Brunner/Mazel; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffman LW. Cross‐cultural differences in childrearing goals. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1988;1988(40):99–122. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Windle M, Brener N, Cuccaro P, et al. Parenting predictors of early-adolescents' health behaviors: simultaneous group comparisons across sex and ethnic groups. J Youth Adolescence. 2010;39(6):594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yabiku ST, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Parsai MB, Becerra D, Del-Colle M. Parental monitoring and changes in substance use among Latino/a and non-Latino/a preadolescents in the Southwest. Substance Use and Misuse. 2010;45(14):2524–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broman CL, Reckase MD, Freedman-Doan CR. The role of parenting in drug use among black, Latino and white adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;5(1):39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez L, Eaton CA, Fairlie AM, Chun TH, Spirito A. Ethnic Group Differences in Substance Use, Depression, Peer Relationships and Parenting among Adolescents Receiving Brief Alcohol Counseling. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9(1):14–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno O, Janssen T, Cox MJ, Colby S, Jackson KM. Parent-adolescent relationships in Hispanic versus Caucasian families: Associations with alcohol and marijuana use onset. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;74:74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luk JW, King KM, McCarty CA, McCauley E, Stoep AV. Prospective Effects of Parenting on Substance Use and Problems Across Asian/Pacific Islander and European American Youth: Tests of Moderated Mediation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78(4):521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark TT, Yang CM, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Racial Differences in Parenting Style Typologies and Heavy Episodic Drinking Trajectories. Health Psychology. 2015;34(7):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shih RA, Miles JN, Tucker JS, Zhou AJ, D'Amico EJ. Racial/ethnic differences in the influence of cultural values, alcohol resistance self-efficacy, and alcohol expectancies on risk for alcohol initiation. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(3):460–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dever BV, Schulenberg JE, Dworkin JB, O'Malley PM, Kloska DD, Bachman JG. Predicting Risk-Taking With and Without Substance Use: The Effects of Parental Monitoring, School Bonding, and Sports Participation. Prevention Science. 2012;13(6):605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merten MJ, Williams AL, Shriver LH. Breakfast consumption in adolescence and young adulthood: parental presence, community context, and obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109(8):1384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Videon TM, Manning CK. Influences on adolescent eating patterns: the importance of family meals. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32(5):365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research. Developmental Review. 2016;41:71–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. In: 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2010: http://umichigan.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=570362. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cordova D, Huang S, Lally M, Estrada Y, Prado G. Do parent-adolescent discrepancies in family functioning increase the risk of Hispanic adolescent HIV risk behaviors? Family Process. 2014;53(2):348–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development , Volume 1, 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1998:993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Latendresse SJ, Ye F, Chung T, Hipwell A, Sartor CE. Parental Monitoring and Alcohol Use Across Adolescence in Black and White Girls: A Cross-Lagged Panel Mixture Model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(6):1144–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blustein EC, Munn-Chernoff MA, Grant JD, et al. The Association of Low Parental Monitoring With Early Substance Use in European American and African American Adolescent Girls. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(6):852–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark DB, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Chung T. Parental supervision and alcohol use in adolescence: developmentally specific interactions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(4):285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patrick ME, Miech RA, Carlier C, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Self-reported reasons for vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the US: Nationally-representative results. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:275–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975-2015: Overview key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Velez-Agosto NM, Soto-Crespo JG, Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer M, Vega-Molina S, Garcia Coll C. Bronfenbrenner's Bioecological Theory Revision: Moving Culture From the Macro Into the Micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017;12(5):900–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.German M, Gonzales NA, Dumka L. Familism Values as a Protective Factor for Mexican-origin Adolescents Exposed to Deviant Peers. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):16–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Shakib S, Palmer PH, Nezami E, Mora J. A Cultural Psychology Approach to “Drug Abuse” Prevention. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39(10-12):1779–1820. doi: 10.1081/JA-200033224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laursen B, Collins WA. Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In: Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development, Vol. 2, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009:3–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.