Abstract

Background

Medical education in this era has been disturbed by coronavirus disease. Our faculty has quickly adapted the curricula to online formats. The online format seems to be more advantageous in terms of content material and virtual activities, but the results of these adjustments will require subsequent evaluation. The aim of this study was to evaluate medical student expectations of online orthopedics learning that was created based on social constructivism theory.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional survey was carried out to assess the fifth-year medical student expectations of our newly developed online orthopedics course during the outbreak. Constructivist Online Learning Environment Survey (COLLES) was applied for evaluating the expectations during orthopedic rotation. The survey contains six aspects based on social constructivist principles: relevance, reflection, interactivity, tutor support, peer support, and interpretation. All students responded to the preferred COLLES before starting the online course, and the actual COLLES was filled out when the online course was completed. Before and after attending the online course, the scores were compared and interpreted to assess student expectations.

Results

A total of 126 fifth-year medical students studied the online orthopedic course. The preferred COLLES were completed by 125 students, while 120 students replied to the actual COLLES. The overall scores from the post-course survey in all aspects were significantly higher than scores from the pre-course with P-value < 0.01. The comparison between the preferred and actual scores showed this online course fulfilled student expectations.

Conclusion

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 19 has disrupted medical student education. The online orthopedic learning course in our department has been developed to deal with the current situation. Using the various activities based on social constructivism theory in the online platform was able to fulfill medical student expectations.

Keywords: Constructivist, Online learning, Medical student, Orthopedic

Highlights

-

•

Medical education in this era has been disturbed by coronavirus disease.

•Transforming to online teaching is expected to solve the problems from traditional.

•Online learning based on constructivism theory is beneficial for medical students.

•The online learning environment survey was applied to evaluate the expectations.

•Using online various constructivist activities was fulfilled student expectations.

1. Introduction

Medical education in this era has been disturbed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Traditional teaching alone cannot achieve the learning objectives; therefore, instructors should quickly adjust the teaching method [1]. Transformation to online teaching is expected to solve this issue. Online healthcare information is currently continually updated, and medical students can easily reach these data to enhance their knowledge [2]. Online teaching provides lecture contents to students at home, in dormitories, or in their preferred place through electronic means and uses class time for practical application activities “anytime/anywhere.” [3]. However, students still convene for some laboratory sessions, simulations, and technology sessions, such as learning plain radiography. In response to the influence of COVID-19, our faculty has immediately adapted to append online learning to traditional in-classroom learning.

The cognitive and social process is the concept of knowledge construction following the Social Constructivism Theory (SCT) [4]. Students gather and assemble meanings by actively collaborating with others by sharing and receiving information. Therefore, to achieve Social Constructivist Learning Environment (SCLE), an interactive process should occur among students, their peers, and instructors by discussing, negotiating, and sharing information. Merging social constructivism with an online format has been proved to be beneficial for medical students [5]. It can provide more time for students to think and effectively share their opinions equally. Consequently, medical students will develop their own knowledge and discover the solution to clinical problems [6].

For isolation and distancing, the transition from learning in the medical school setting to home is needed, and a well-established online course is also required. Instructors should take responsibility for designing and constructing active online activities for medical students. Therefore, the newly generated the interactive online course in orthopedics based on SCT was created. However, this course has not been evaluated. Thus, this study was conducted to investigate the extent to which online learning components in our teaching fulfilled medical student expectations through an online survey.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted during the 2020 to 2021 academic year at Prince of Songkla University, Thailand. During the fifth year of our Doctor of Medicine program, all medical students are required to take part in orthopedic and rehabilitation rotation for one month. In the last academic year, we provided only in-classroom learning courses for medical students. However, we have recently adjusted this course due to the widespread coronavirus. In the four weeks of rotation, we separated this course into one week of online learning and followed by three weeks of clinical rotation, for studying actual patients on the ward, outpatient clinic, in-patient clinic, and operating room. For evaluating our course, the survey was carried out among fifth-year medical students before starting and after finishing the rotation, using online self-administered questionnaires. This study was investigated just solely by fifth-year medical students. The medical students who filled in the questionnaire completely were included in this study. The questionnaires completed by a total of 126 students were interpreted. The present study was approved by the Prince of Songkla University Institutional Review Board and has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria [7]. The study was registered in the research registry with Unique Identifying number 6775, and the link is https://www.researchregistry.com/register-now#home/registrationdetails/6087ef77dfbf1b001b01bbd0.

2.2. Online materials

The Orthopaedics Committee designed the competency-based online course as initiated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2001 for emphasizing the educational outcomes in terms of competencies to be achieved during training [8,9]. Six domains, including medical knowledge, patient care, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, practice-based learning and improvement, and system-based practice, were evaluated. Therefore, our objectives of the online course were (1) Having responsibility in the task which the students are assigned by using various technologies, (2) Core medical knowledge in orthopedic science, (3) Showing how to interpret the basic common fracture, (4) Showing how to communicate during activities and (5) Able to answer the clinical question by using evidence-based medicine.

The online learning management system used in this study was developed by the Prince of Songkla University. The e-learning components can be developed, uploaded, and monitored by course tutors to ensure that the contents are relevant, up-to-date, and interesting. This online learning management system was aimed to stimulate, deliver, guide, and manage learning processes. Using this system, tutors can upload any types of teaching materials, such as lecture slides, audio files, videos, and online quizzes. The medical students and instructors can assess this online system after enrollment by authorized instructors.

The online orthopedic course is included with various interactive activities such as online lectures and live meetings with medical educators via zoom application (traumatic film interpretation, upper limb disease case discussion, lower limb disease case discussion, assignment learning in spine disease, and quizzes). Our department assigned medical instructors as mentors in each group to monitor the online course and receive feedback from our students. In online lectures, the students have to perform self-study via video streaming conducted by medical instructors as one lecture per hour, 12 lectures from Monday to Friday in that week. For traumatic film interpretation, students were assigned one film each to present and interpret with medical instructors via the online application. For the case discussion activities, we chose common and simple cases, consisting of 2 cases with upper limb diseases and 2 cases with lower limb disease. For online assignments, the questions related to common spine problems were assigned to each student. We expected them to find the answer using evidence-based medicine. The students have to prepare and present the completed assignments to the medical instructor through an online application. One instructor was assigned to support five students in the discussion part, and another teacher was assigned to provide support for all students in each rotation. In the traumatic film interpretation and assignment learning in spine disease, all students had to discuss the stages with their peers and the instructor, sharing their opinions through linking reflective thinking, interactivity, interpretation, and peer support.

2.3. Questionnaire for assessment

The online orthopedic course contained interactive and collaborative activities that were created based on constructivism theory. Therefore, the Constructivist Online Learning Environment Survey (COLLES) developed by Taylor and Mayor was used in this study [10]. The COLLES contains six aspects, with each aspect being represented by four items, resulting in 24 items for the whole survey instrument. These aspects reflect the social constructivist principles, making them suitable to be used for the assessment of teachings that are based on SCT. The SCLE aspects that are assessed by the COLLES include (1) relevance: the extent to which the students think e-learning is relevant to their professional practices; (2) reflection: the extent to which e-learning promotes students’ reflective critical thinking; (3) interactivity: the extent to which students engage interactively with other students and tutors; (4) tutor support: the extent to which tutors support the engagement of students in e-learning (4 items); (5) peer support: the extent to which fellow friends provide sensitive and encouraging support; and (6) interpretation: the extent to which students and tutors make good sense of meaning in a congruent and connected manner.

To measure the expectations of the online course environment, we used two forms of COLLES at different times, “preferred COLLES” and “actual COLLES,” completed at the beginning and the end of a semester, respectively. The expectations of the online learning environment (preferred and actual) were assessed by averaging all items (24 items) to calculate the mean overall COLLES scores or averaging each scale's scores. Both preferred and actual COLLES are available online and are free to use.

2.4. Data collection

The survey was embedded within the online orthopedic course. All of the students who participated in this online course were encouraged to complete both survey forms. All of them were offered anonymity and confidentiality. Their responses in the survey did not influence their assessment marks or final grades. Completion and return of the questionnaire by the participants implied consent.

2.5. Data analysis

The data was analyzed using R program Version 3.4.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria). Demographic data were shown in mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentages for discrete variables. Comparing the preferred (pre-course) and actual (post-course) COLLES scores was performed, using the paired T-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test as appropriate. Medical students were considered satisfied with this online learning if there was no significant difference between the preferred and actual COLLES scores, or actual COLLES scores were significantly greater than the preferred COLLES scores. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Of the 126 fifth-year medical students who attended the online orthopedic course, 125 students completed the preferred COLLES while 120 completed the actual COLLES. There were 64 male and 61 female students in this study. Demographic data was shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of included medical students.

| Characteristics | Numbers (Percent) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 64 (50.8) |

| Female | 62 (49.2) |

| Questionnaire completeness | |

| Preferred COLLES | 125 (99.2) |

| Actual COLLES | 120 (95.2) |

COLLES Constructivist Online Learning Environment Survey.

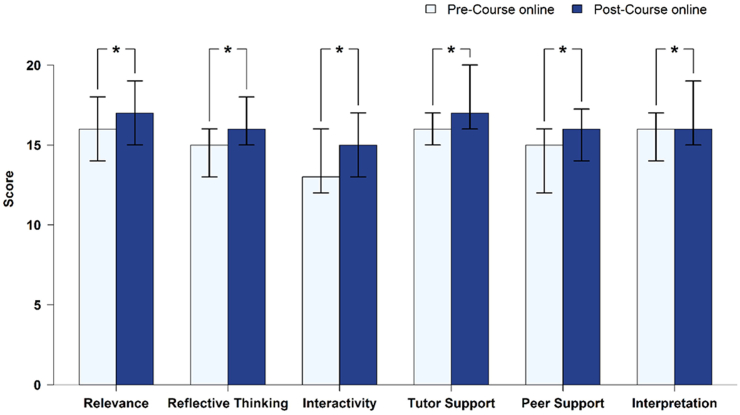

A comparison of median scores between preferred COLLES and actual COLLES of each aspect of SCLE, including relevance, reflective thinking, interactivity, tutor support, peer support, and interpretation, was presented in Table 2. There was a statistically significant difference in all aspects with P-value < 0.01. The overall median scores of the relevance aspect were 16 (14,18) in preferred COLLES with an improvement to 17 (15,19) in actual COLLES. In terms of reflective thinking, the median scores in preferred COLLES were 15 (13–16), while the actual median scores were 16 (15,18). The preferred and actual median scores of interactivities were 13 (12,16) and 15 (13,17), respectively. The preferred median score of tutor support was 16 (15,17), and the actual was 17 (16,20). The preferred median scores were 15 (12,16), and the actual scores were 16 (14,17.2) in the peer support aspect. The last aspect was interpretation, with median preferred scores 16 (14, 17) and 16 (15,19) in actual scores. The summary of the comparison between preferred and actual COLLES scores (pre-and post-course) was illustrated in Fig. 1. These findings show a significant increase in overall mean scores in all aspects of SCLE. The two highest overall actual COLLES scores were in relevance and tutor support aspect.

Table 2.

Scores obtained from the online survey comparing between pre-course and post-course.

| SCLE Aspects | Preferred COLLES scores (n = 125) |

Actual COLLES scores (n = 120) |

P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | P25 | P75 | Median | P25 | P75 | ||

| Relevance | |||||||

| Focus on interesting issues | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Important to my practice | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Improve my practice | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Connects with my practice | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Overall | 16 | 14 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 19 | <0.01 |

| Reflective Thinking | |||||||

| I'm critical of my learning | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| I'm critical of my own ideas | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4.2 | |

| I'm critical of other students | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| I'm critical of readings | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Overall | 15 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 18 | <0.01 |

| Interactivity | |||||||

| I explain my ideas | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| I ask for explanations | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| I'm asked to explain | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Students respond to me | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Overall | 13 | 12 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 17 | <0.01 |

| Tutor Support | |||||||

| Tutor stimulates thinking | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4.5 | 4 | 5 | |

| Tutor encourages me | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Tutor model discourse | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Tutor models self-reflection | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Overall | 16 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 20 | <0.01 |

| Peer Support | |||||||

| Students encourage me | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| Students praise me | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Students value me | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Students empathies | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Overall | 15 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 17.2 | <0.01 |

| Interpretation | |||||||

| I understand other students | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Students understand me | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| I understand the tutor | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Tutors understand me | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Overall | 16 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 19 | <0.01 |

SCLE Social Constructivist Learning Environment; COLLES Constructivist Online Learning Environment Survey; P25 25th percentile; P75 75th percentile.

Fig. 1.

Overall scores in each aspect of Constructivist Learning Environment comparing between pre-course (Preferred COLLES) and post-course (Actual COLLES).

4. Discussion

Assessing from the COLLES questionnaire, higher scores were obtained after attending the new online orthopedic course. This course was beyond medical student expectations in all SCLE aspects, comprising relevance, reflective thinking, interactivity, tutor support, peer support, and interpretation. This may imply that they preferred online learning experience due to our online contents and activities related to their practices, encouraged critical thinking, and allowed interactions with peers and tutors. Receiving support from both tutors and peers was also important for them.

The online orthopedic course met the fifth-year medical student expectations, which can be seen from the scores being significantly improved from pre-course to post-course. Compared to a previous study, Sthapornnanon N et al. reported no significant difference between actual COLLES and preferred COLLES scores were found in thirty third-year pharmacy students using an online introductory module of Pharmacy Professional Practice in Pharmaceutical Marketing and Business in an 8-week course [5]. However, assuming that the post-course scores are not different from their expected scores before starting the course, they concluded that students' expectations were fulfilled after taking part in the online pharmaceutical course, developed based on social constructivism theory. The possible reasons to explain the minor difference being that this was an online orthopedic course, while the previous study was a pharmaceutical course. Consequently, there was a variation in the activities and also course objectives. Additionally, course learning duration may affect the findings. Medical students need to spend only one week on our course, while they needed two months in the pharmacy education program.

The highest overall post-course scores were in relevance and tutor support aspect. These findings proved that students were most satisfied with learning focused on their interests or professional practice as well as stimulating them to think or participate by active instructors. The creation of an easily-accessed online web friendly environment for all students was intended to encourage them to share opinions and dare to discuss them in an online orthopedic course. Due to the friendly environment that facilitates learning, students were comfortable giving comments or opinions to peers and instructors during interactive activities, including film interpretation and case-based discussion [11,12]. A qualitative study using focus groups and interviews in 50 physicians by Sargeant J et al. also supported that key roles of facilitating created a comfortable learning environment and increased educational value of discussions [13]. Other than that, instructors were assigned as advisory teachers for coaching and supervising medical students throughout the online course; therefore, the medical students could report any problems or inconveniences while attending the online course.

Having instructors for course orientation could facilitate introduction and welcome all students at the course beginning. Also, facilitating introductions and sharing experiences in an informative manner during activities were helpful. Emphasizing what students should acquire by instructors was necessary [14]. In this online course, instructors guided students in every activity and highlighted the responsibility to complete the assignments. Moreover, providing effective small-group learning, instructors' thoughtful use of techniques facilitated constructive interaction based on learner's needs and practice and contributed to the educational value of interpersonal interactions, especially in the activities using case-based discussion to link with this result. Several previous studies also stated that small-group face-to-face learning and learning theory can inform the educational design and facilitation of online learning [13,15]. Vaona et al. conducted a systematic review comparing e-learning programs versus traditional learning at 12-month follow-up including 16 studies with randomized trial involving 5679 licensed health professionals (4759 mixed health professionals, 587 nurses, 300 doctors, and 33 childcare health consultants) and found that the teacher-student ratio should be reduced to successfully train the students [16]. For live activities (Traumatic film interpretation, Case discussion, Evidence-based learning), one tutor takes responsibility to teach five medical students per group. Therefore, this hypothesis may be effective in facilitating the medical students as the actual score was improved. Besides, scores from reflective thinking, interactive aspects were improved; however, there were some limitations about interactive knowledge in online learning because of the time constraints of a one-week course. There was not much time to allow all students to reflect on their thinking entirely. Moreover, some students ignored performing self-learning before the class, which led to one-way communication and lack of response from them.

Following the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2001, this course emphasized the educational outcomes in terms of competencies to be achieved during an online course. At this point, it was important to design a course that depended on competencies rather than adapting to the expectations of learners [16]. From our findings, the online orthopedic course that was developed achieved students' expectations. However, whether medical students were reaching these competencies, was not explored. Further studies in the relation of online learning courses and learning competencies are suggested.

This study has some limitations. This research was conducted in a single-center academic hospital with only fifth-year medical students in orthopedic rotation. The generalization of the results in this study to other departments or pre-clerkship students might be of concern. Applying to different study populations may change the findings. Moreover, baseline characteristics and attitudes of students that possibly affected the student expectations were not explored. Lastly, the sample size was not calculated to demonstrate the differences; however, data from all possible participants attending orthopedic rotation in the recent academic year was collected.

5. Conclusion

The outbreak of widespread coronavirus disease 19 has disrupted medical student education. An online orthopedic learning course in has been developed by our department to deal with the current situation. Using the various activities based on social constructivism theory, the online platform can fulfill the medical students’ expectations in the aspects of relevance, reflection, interactivity, tutor support, peer support, and interpretation. Even though this online course met student expectations, the effectiveness of the course needs further verification.

Ethical approval

The present study was approved by the Prince of Songkla university Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine, Songklanagarind Hospital, Prince of Songkla University (IRB number EC 63-217-11-1).

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

This study was conducted using online platforms. The participants interested in this study freely completed and submitted the questionnaire. They could ignore performing if they were not interested in participating in the study.

Author contribution

All authors involved in study conceptualization and design. Sitthiphong Suwannaphisit: Methodology, Data analysis, Writing - Original Draft Theerawit Hongnaparak: Data interpretation, Supervision Jongdee Bvonpanttarananon: Acquisition of data Chirathit Anusitviwat: Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: Researchregistry.com.

-

2.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry6775.

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/register-now#home/registrationdetails/6087ef77dfbf1b001b01bbd0/

Guarantor

Sitthiphong Suwannaphisit Department of Orthopedics, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University 15 Karnjanavanich Road, Hat Yai, Songkhla 90110, Thailand Email Address: aunsittipong@gmail.com.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Nannapat Pruhetkaew of the Epidemiology Unit, Faculty of Medicine, for providing statistical support. We also thank Dave Patterson for English editing the first draft and Geoffrey Cox of the International Affairs Department, Prince of Songkla University, for English editing the final draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102493.

Contributor Information

Sitthiphong Suwannaphisit, Email: aunsittipong@gmail.com.

Chirathit Anusitviwat, Email: chirathit.a@psu.ac.th, chirathit.a@psu.ac.th.

Theerawit Hongnaparak, Email: theerawit.h@gmail.com.

Jongdee Bvonpanttarananon, Email: sjongdee@medicine.psu.ac.th.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pei L., Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Educ. Online. 2019;24:1666538. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2019.1666538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold-Garza S. The flipped classroom teaching model and its use for information literacy instruction. 2014. [DOI]

- 4.Kim J.S. The effects of a constructivist teaching approach on student academic achievement, self-concept, and learning strategies. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2005;6:7–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03024963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sthapornnanon N., Sakulbumrungsil R., Theeraroungchaisri A., Watcharadamrongkun S. Social constructivist learning environment in an online professional practice course. Am. J. Pharmaceut. Educ. 2009;73:10. doi: 10.5688/aj730110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wertsch J.V., Tulviste P. L. S. Vygotsky and contemporary developmental psychology. Dev. Psychol. 1992;28:548–557. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.4.548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R., Abdall-Razak A., Crossley E., Dowlut N., Iosifidis C., Mathew G., Strocss Group STROCSS 2019 Guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2019;72:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swing S.R. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med. Teach. 2007;29:648–654. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rani M., Rahman S. Competency-based medical education, here next? 2018. [DOI]

- 10.Taylor P., Maor D. 2000. Assessing the Efficacy of Online Teaching with the Constructivist On-Line Learning Environment Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meo S.A. Basic steps in establishing effective small group teaching sessions in medical schools. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2013;29:1071–1076. doi: 10.12669/pjms.294.3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karani R. Enhancing the medical school learning environment: a complex challenge. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015;30:1235–1236. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargeant J., Curran V., Allen M., Jarvis-Selinger S., Ho K. Facilitating interpersonal interaction and learning online: linking theory and practice. J. Continuing Educ. Health Prof. 2006;26:128–136. doi: 10.1002/chp.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vega C., McAnally-Salas L., Gilles L. Attitudes and perceptions of students in a systems engineering e-learnig course. Acta Didact. Napoc. 2009;2 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muñoz-Castro F.J., Valverde-Gambero E., Herrera-Usagre M. Predictors of health professionals' satisfaction with continuing education: a cross-sectional study. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2020;28:e3315. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.3637.3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaona A., Banzi R., Kwag K.H., Rigon G., Cereda D., Pecoraro V., Tramacere I., Moja L. E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018;1:CD011736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011736.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.