Key Points

Question

Which characteristics of patients with infantile hemangioma (IH) are associated with a higher or lower risk of PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies) syndrome?

Findings

In this cohort study of 242 patients with IH, higher-risk features associated with PHACE syndrome were IH that involved 3 or more locations and a surface area of 25 cm2 or greater. Involvement of the parotid gland and S2 segment were associated with a significantly lower but still present risk of PHACE syndrome; race and ethnicity may also be associated with risk.

Meaning

These associations with risk of PHACE can guide practitioners in performing diagnostic evaluation and treatment initiation as well as improving counseling of patients’ families.

Abstract

Importance

A 2010 prospective study of 108 infants estimated the incidence of PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies) syndrome to be 31% in children with facial infantile hemangiomas (IHs) of at least 22 cm2. There is little evidence regarding the associations among IH characteristics, demographic characteristics, and risk of PHACE syndrome.

Objectives

To evaluate demographic characteristics and comorbidities in a large cohort of patients at risk for PHACE syndrome and assess the clinical features of large head and neck IH that may be associated with a greater risk of a diagnosis of PHACE syndrome.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, retrospective cohort study assessed all patients with a facial, head, and/or neck IH who were evaluated for PHACE syndrome from August 1, 2009, to December 31, 2014, at 13 pediatric dermatology referral centers across North America. Data analysis was performed from June 15, 2017, to February 29, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was presence or absence of PHACE syndrome. Data included age at diagnosis, sex, patterns of IH presentation (including size, segment location, and depth), diagnostic procedures and results, and type and number of associated anomalies.

Results

A total of 238 patients (mean [SD] age, 2.96 [4.71] months; 184 [77.3%] female) were included in the analysis; 106 (44.5%) met the criteria for definite (n = 98) or possible (n = 8) PHACE syndrome. A stepwise linear regression model found that a surface area of 25 cm2 or greater (odds ratio [OR] 2.99; 95% CI, 1.49-6.02) and involvement of 3 or more locations (OR, 17.96; 95% CI, 6.10-52.85) to be statistically significant risk factors for PHACE syndrome. Involvement of the parotid gland (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.18-0.85) and segment S2 (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.16-0.91) was associated with a lower risk. Race and ethnicity may also be associated with PHACE syndrome risk, although more studies are needed.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study further described factors associated with both a higher and lower risk of PHACE syndrome. The presence of multiple anatomical sites and large surface area were associated with greater risk, whereas S2 or parotid IHs were associated with lower, but still potential, risk. These findings can help in counseling families and decision-making regarding evaluation of infants with large head and neck IHs.

This cohort study evaluates demographic characteristics and comorbidities in patients at risk for PHACE syndrome and examines clinical features of large head and neck infantile hemangiomas that may be associated with a greater risk of the diagnosis of PHACE syndrome.

Introduction

PHACE(S) (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies [with sternal clefting or supraumbilical raphe]) syndrome is the association of large facial infantile hemangiomas (IHs) with structural anomalies of the brain, eye, heart, and arteries; central nervous system arterial anomalies are seen most frequently.1 Depending on the associated abnormalities present, patients may be especially at risk for neurologic complications, including developmental delays, cognitive impairment, and, rarely, stroke.2,3 Patients often require multidisciplinary management from several specialties, including pediatric dermatology, neurology, otolaryngology, radiology, cardiology, general surgery, neurosurgery, endocrinology, and ophthalmology.

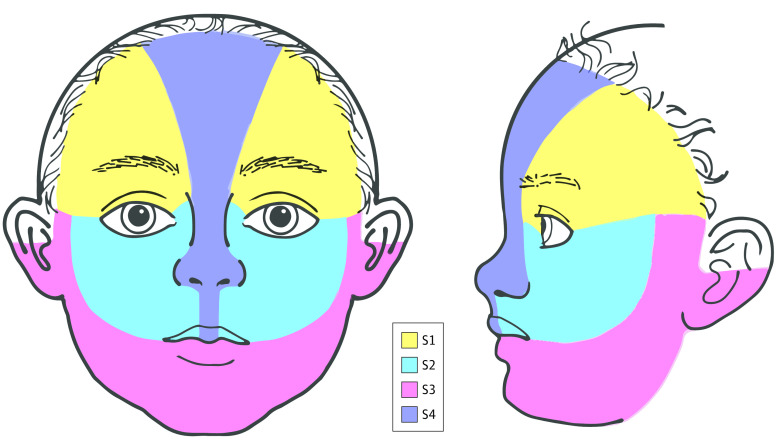

To our knowledge, the only prospective study4 performed to date evaluating the risk of PHACE syndrome in patients with facial IHs of at least 22 cm2 found an overall risk of 31%. Larger IHs and involvement of more than 1 facial segment (as defined by Haggstrom et al5) were risk factors for PHACE syndrome diagnosis. Frontotemporal (S1) and mandibular (S3) segments were frequently involved in patients with PHACE syndrome, whereas involvement of the maxillary segment (S2) was much less common (Figure 1). However, the prevalence of facial segments involved in patients without PHACE syndrome was not reported, and conclusions regarding the risk associated with these segments cannot be drawn.

Figure 1. Isolated Segmental Infantile Hemangioma of the Maxillary (S2) Segment in a Patient With Definite PHACE (Posterior Fossa Malformations, Hemangioma, Arterial Anomalies, Cardiac Defects, Eye Anomalies) Syndrome.

This S2 hemangioma spares the preauricular cheek.

In our review of the literature, most published photographs of patients with PHACE syndrome showed an IH with a superficial component. We hypothesize that children with large, purely deep IHs or those IHs limited to S2 or the parotid gland may have a far lower risk of PHACE syndrome than other patients with large superficial or mixed facial IHs. Therefore, these patients may not need to undergo a comprehensive evaluation for PHACE syndrome. This study aimed to assemble a retrospective cohort of pediatric patients with IHs of the face, neck, and/or scalp who were evaluated for PHACE syndrome to determine which clinical and/or demographic characteristics may be associated with a higher or lower risk of the syndrome.

Methods

Thirteen large pediatric dermatology centers in the US and Canada participated in the study. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each center. Sites reviewed all patients who were evaluated for PHACE syndrome between August 1, 2009, and December 31, 2014. Sites were required to have performed a minimum of 10 PHACE syndrome evaluations during the study period to ensure they had sufficient expertise in evaluating for the presence of PHACE syndrome. If records were not accessible back to 2009, a mean of 2 evaluations per year was required. These sites were recruited via the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Those whose evaluations were performed at multiple institutions were excluded to eliminate the risk of duplicating patients. Data analysis was performed from June 15, 2017, to February 29, 2020. One site (Boston Children’s Hospital) required written consent, which was obtained from the parent or legal guardian of each patient. A waiver of informed consent was obtained from each remaining site's institutional review board. Data were deidentified. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Patients were identified in the electronic medical record using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes for hemangioma or through photographic archives that were created as part of standard clinical record keeping. All patients between the ages of 0 and 4 years with a large IH on or above the neck who underwent a PHACE syndrome evaluation with high-quality clinical photographs or diagrams, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck were included.

For patients who met the inclusion criteria, the following data were collected: IH characteristics at presentation, including location (facial segment), size (surface area additive for multiple IHs), depth (superficial, deep, or mixed), and parotid involvement if present clinically; demographic characteristics, including race (White, race other than White, and unknown) and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic, and unknown); results of PHACE syndrome–related diagnostic studies (MRI, MRA, echocardiography, or eye examination); and type and number of associated anomalies (posterior fossa, arterial, cardiac, eye, and sternal or supraumbilical). Data were entered into Medrio, an online Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant database.

Facial segment location was based on the locations described by Haggstrom et al.5 The preauricular cheek was classified as part of S3 based on updated facial segment maps (Figure 1 and Figure 2).6 In addition, separate scalp and neck categories were included. Location of the IH was confirmed by 1 of 3 methods, depending on the transmitting institution’s institutional review board: (1) photographs were uploaded in their original form to a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant database, (2) photographs were deidentified and then uploaded, or (3) boundaries of the IH were traced onto a standardized facial diagram and then uploaded. These photographs and standardized diagrams were then reviewed by 2 authors (I.J.F. and A.N.H.) to verify segment classification and maintain consistent classification throughout the cohort. Bilateral involvement of the same location (eg, bilateral S3) was considered to be involvement of 2 locations. Because there are no defined segments for the scalp or neck, each of these was considered as its own location.

Figure 2. Infantile Hemangioma Facial Segment (S1-S4) Boundaries With Modifications From the Original Map of Haggstrom et al5.

For many IHs, exact measurements were not recorded in the medical record. To include these patients, a single investigator (C.H.C.) estimated the maximum diameter horizontally and vertically as less than 5 cm, 5 to 10 cm, 10 to 15 cm, 15 to 20 cm, or greater than 20 cm. The estimated diameters were calculated using mean facial measurements compiled during nonrandom sequential pediatric dermatology visits of any chief concerns for infants 0 to 4 months of age (eFigure in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Presence or absence of PHACE syndrome was determined by strict application of the 2016 consensus criteria.7 The statistical significance of the association between measured variables and PHACE syndrome was assessed with the χ2 test for categorical variables and the 2-sided t test for continuous variables. P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. Covariate effect on PHACE syndrome diagnosis was evaluated using multivariable logistic regression (SAS software, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Main Outcomes

A total of 238 patients (mean [SD] age, 2.96 [4.71] months; 184 [77.3%] female) met the inclusion criteria. Four of these patients had localized IHs smaller than 5 cm in diameter and were thus excluded from the analysis; none had PHACE syndrome. Of the remaining 238 patients, 106 (44.5%) were diagnosed with PHACE syndrome, 98 with definite PHACE syndrome and 8 with possible PHACE syndrome. For the purposes of our analyses, patients with possible PHACE syndrome were assumed to have PHACE syndrome to avoid underestimating the true risk of the condition. The breakdown of individual major and minor criteria used to meet the diagnosis of PHACE syndrome are outlined in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Table 1 summarizes patient demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics of IH in patients with and without PHACE syndrome. Sex, birth weight, race, ethnicity, and gestational age did not have an association with PHACE risk. The IH characteristics that were significantly related to PHACE syndrome risk from these unadjusted data were bilaterality, involvement of 3 or more locations, surface area of 25 cm2 or larger, and involvement of S1, S4, neck, and scalp locations.

Table 1. Demographic and IH Characteristics for Patients With and Without PHACE Syndromea.

| Demographic or clinical characteristic | PHACE syndrome diagnosis | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 106) | No (n = 132) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 80 (75.5) | 104 (78.8) | NA | .56 |

| Male | 26 (24.5) | 28 (21.2) | NA | |

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wkb | 38.1 (2.7) | 38.3 (2.2) | NA | .51 |

| Race | NA | |||

| White | 67 (63.2) | 98 (74.2) | NA | .06 |

| Other than White | 18 (17.0) | 10 (7.6) | NA | |

| Asian | 13 (12.3) | 2 (1.5) | NA | |

| Black or African American | 3 (2.8) | 6 (4.5) | NA | |

| Asian and White | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | NA | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 1 (0.8) | NA | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.9) | 0 | NA | |

| Unknown | 21 (19.8) | 24 (18.2) | NA | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 23 (21.7) | 14 (10.6) | NA | .06 |

| Non-Hispanic | 66 (62.2) | 93 (70.5) | NA | |

| Unknown | 17 (16.0) | 25 (18.9) | NA | |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), kgc | 3.3 (0.72) | 3.2 (0.74) | NA | .29 |

| IH characteristics | ||||

| Depth | ||||

| Purely superficial | 42 (39.6) | 50 (37.9) | NA | .06 |

| Mixed | 59 (55.7) | 64 (48.5) | NA | |

| Purely deep | 5 (4.7) | 18 (13.6) | NA | |

| Characterization | ||||

| Segmental | 98 (92.5) | 115 (87.1) | NA | .18 |

| Indeterminate | 8 (7.5) | 17 (12.9) | NA | |

| Parotid | 17 (16.0) | 34 (25.8) | 0.55 (0.29-1.05) | .07 |

| Bilateral | 40 (37.7) | 18 (13.6) | 3.84 (2.04-7.23) | <.001 |

| Location | ||||

| S1 | 62 (58.5) | 48 (36.4) | 2.47 (1.46-4.17) | <.001 |

| S2 | 21 (19.8) | 30 (22.7) | 0.84 (0.45-1.57) | .59 |

| S3 | 61 (57.5) | 60 (45.5) | 1.63 (0.97-2.72) | .06 |

| S4 | 28 (26.4) | 14 (10.6) | 3.03 (1.50-6.12) | .002 |

| Scalp | 35 (33.0) | 19 (14.4) | 2.93 (1.56-5.52) | <.001 |

| Neck | 30 (28.3) | 22 (16.7) | 1.97 (1.06-3.68) | .03 |

| Area ≥25 cm2 | 85 (80.2) | 67 (50.8) | 3.93 (2.18-7.06) | <.001 |

| No. of locations | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 55 (51.9) | 120 (90.9) | 9.27 (4.58-18.8) | <.001 |

| ≥3 | 51 (48.1) | 12 (9.1) | ||

Abbreviations: IH, infantile hemangioma; NA, not applicable; PHACE, posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Data available for only 193 patients (85 with PHACE syndrome and 108 without).

Data available for only 145 patients (63 with PHACE syndrome and 82 without).

Using the presence of IH in only 1 location as the reference group, we performed a logistic regression with PHACE syndrome as the outcome variable and the number of locations involved as the risk variable. No significant difference in risk of PHACE syndrome between 1 and 2 locations was found. The largest statistically significant increase was 3 locations involved compared with 1 location (OR, 9.61; 95% CI, 3.63-25.42). This finding prompted the collapse of the locations variable into 2 groups for subsequent analyses: those with 1 to 2 locations and those with 3 or more locations.

A multivariable logistic regression was then performed (Table 2). Because of the degree of interrelatedness of various IH characteristics, all these variables were included in the model even if they did not appear statistically significant in a univariate analysis. We used a stepwise regression method where variables were required to have a significance level of .80 to enter the model and a significance level of .10 to remain. The value of .80 was chosen to give as many variables as possible a chance to enter the model. After other variables were controlled for, race other than White (OR, 3.25; 95% CI, 1.23-8.60), Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 3.00; 95% CI, 1.15-7.83), involvement of 3 or more locations (OR, 17.96; 95% CI, 6.10-52.85), and area of 25 cm2 or larger (OR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.49-6.02) were independently associated with a statistically significant increased risk of PHACE syndrome over reference. Any involvement of parotid (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.18-0.85), S2 (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.16-0.91), or neck (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.10-0.81) was independently associated with a statistically significant decreased risk of PHACE syndrome.

Table 2. Multivariable Logistic Regression Using a Stepwise Selection Model for the Presence of PHACE Syndrome.

| Characteristic | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| Other than White | 3.25 (1.23-8.60) | .03 |

| Unknown | 1.15 (0.47-2.81) | .36 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 3.00 (1.15-7.83) | .01 |

| Unknown | 0.80 (0.32-1.97) | .09 |

| Parotid IH | 0.39 (0.18-0.85) | .02 |

| ≥3 Locations involved | 17.96 (6.10-52.85) | <.001 |

| S2 involvement | 0.38 (0.16-0.91) | .03 |

| Neck involvement | 0.28 (0.10-0.81) | .02 |

| Area ≥25 cm2 | 2.99 (1.49-6.02) | .002 |

Abbreviations: IH, infantile hemangioma; PHACE, posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies.

The direction of the association between PHACE syndrome and neck involvement changed from increased risk to decreased risk after other variables were controlled for. To determine whether this was the result of collinearity with other variables in our model or if there was a confounding variable not accounted for, the degree of collinearity with other variables was assessed. Those with the highest degree of collinearity were bilateral involvement, 3 or more locations, and S3 involvement. When these variables were excluded from our logistic regression model, the direction of the association did not change, indicating that when these 3 factors are controlled for, neck location is associated with a lower risk of PHACE syndrome.

Subgroup Analyses

To better evaluate the risk of isolated S2 and isolated parotid IH, subgroup analysis was performed of unilateral single-location IHs (Table 3). Rates of PHACE syndrome in each location as well as multiple locations were compared to the rate of 31% found in the original prospective cohort study by Haggstrom et al.4 The risk of individual segments was not statistically different when compared with this cohort; however, involvement of multiple segments or locations was associated with a significantly higher risk of PHACE syndrome.

Table 3. Subgroup Analysis of Unilateral Single-Location Infantile Hemangioma.

| Location | PHACE syndrome diagnosis, No. (%) | Positive for definite or possible PHACE syndrome, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite (n = 98) | Possible (n = 8) | No (n = 135) | ||

| S1 only | 14 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | 22 (16.3) | 40.5 |

| S2 only | 3 (3.1) | 1 (12.5) | 19 (14.1) | 17.8 |

| S3 only | 12 (12.2) | 0 | 33 (24.4) | 26.7 |

| S4 only | 1 (1) | 0 | 5 (3.7) | 16.7 |

| Scalp only | 2 (1.5) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (1.5) | 60.0 |

| Neck only | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 2 (1.5) | 33.3 |

| Multiple | 66 (67.3) | 4 (50.0) | 52 (38.5) | 57.4a |

Abbreviation: PHACE, posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies.

Statistically significant at P < .05.

Stepwise logistic regressions were performed in subcohorts of single-location IHs and multiple-location IHs. Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 4.14; 95% CI, 1.33-12.86) and surface area of 25 cm2 or larger (OR, 5.51; 95% CI, 2.23-13.60) were statistically significant factors associated with increased risk of PHACE syndrome in the unilateral single-location IHs. Among multiple-location IHs, S3 (OR, 3.52; 95% CI, 1.08-11.53) and scalp involvement (OR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.09-7.74) were significantly associated with an increased risk of PHACE syndrome. Notably, there were no purely superficial single-location IHs and only 2 purely deep IHs that covered multiple locations.

Four of 23 patients with isolated S2 IHs had PHACE syndrome. There were no specific S2 patterns (eg, contiguous lower eyelid involvement) associated with PHACE syndrome. Among the 32 isolated parotid IHs in the study cohort, 15 were purely deep. Three of 15 patients with purely deep isolated parotid IHs had PHACE syndrome.

Discussion

This cohort study assembled a substantial number of patients with large head and/or neck IHs to assess which IH segments are associated with both a higher and lower risk of PHACE syndrome. This work is important for several reasons. Propranolol has become the standard of care for treatment of large IHs. There is a potential risk of using a blood pressure–lowering agent in patients who may be at increased risk for ischemic injury and stroke because of arterial anomalies, although a previous retrospective study8 found that oral propranolol appears safe to use in patients with PHACE syndrome irrespective of stroke risk. Severe coarctation of the aorta, a potential feature of PHACE syndrome, is a contraindication to using β-blocker therapy. Conversely, delaying the initiation of propranolol therapy until an evaluation for PHACE syndrome can be completed may increase the risk of complications from the IH (eg, ulceration or visual obstruction).

Another issue is the need for general anesthesia during PHACE syndrome evaluation. Caution regarding the potential effects of general anesthesia on the developing brain in young infants has recently been emphasized.8,9 Many infants require general anesthesia for MRI and MRA with gadolinium contrast to fully evaluate for PHACE syndrome. Gadolinium contrast is deposited in the brain of otherwise healthy patients, including children, and its effect is not fully known.9,10 Substantial time and cost are associated with obtaining these imaging techniques, including hospital admission, which may be required to expedite PHACE syndrome evaluation.

Several studies4,11 have confirmed that infants with facial IH currently or expected to grow to 5 cm or larger in diameter are at risk for PHACE syndrome. This study emphasizes that this risk is not uniform. A strong case can be made for expediting a full PHACE syndrome evaluation in those patients with the highest risk (eg, ≥3 locations or surface area ≥25 cm2). For those with features associated with lower risk of PHACE syndrome (eg, parotid IH or S2 involvement), the decision regarding timing of evaluation can include shared decision-making by the physician and parents. This decision-making includes considering deferral of complete evaluation until an age when the risk of general anesthesia decreases. If other signs or symptoms, such as developmental delay, headache, hearing loss, or characteristic dental anomalies,7,12 are found, then a complete PHACE syndrome evaluation is certainly indicated, even if originally deferred.

Patients with PHACE syndrome were present in every group, including low-risk groups (eg, S2 or unilateral parotid). Some practitioners have considered performing a modified PHACE syndrome workup for patients perceived to be lower risk with echocardiography and ophthalmologic examination performed without MRI and MRA. However, the data from this study suggest that this limited workup, even if the results are entirely normal, may provide a false sense of security. All 7 low-risk patients (unilateral deep parotid and unilateral S2) who had PHACE syndrome had cerebral arterial anomalies (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Because the study relied on MRI and MRA reports rather than formal review of images, independent risk stratification was not possible. However, several of the low-risk patients had cerebrovascular anomalies of multiple vessels. Only 1 of these patients had abnormalities on an echocardiogram that would have prompted an MRI and MRA to complete the PHACE syndrome workup.

Although S1 has been considered to be a high-risk location in clinical practice, the current study raises the possibility that location alone may not be directly responsible for the higher risk seen. Analysis of these data suggests that involvement of multiple other facial segments and larger area are more important in determining PHACE syndrome risk. Once these were controlled for, the S1 segment was no longer significantly associated with risk of PHACE syndrome. The possibility that there is a subset of S1 IH patterns that may be associated with higher risk of PHACE syndrome was not evaluated in this study. In clinical practice, it may be more helpful for practitioners to focus on the size of the IH and how many segments are involved rather than focusing purely on segment location.

Involvement of the neck deserves special consideration. It initially appeared in the univariate analysis that neck involvement was associated with an increased risk of PHACE syndrome. However, after bilateral involvement, 3 or more locations, and S3 location were controlled for, neck location remained significantly associated with PHACE syndrome but actually appeared to be protective. Therefore, we cannot make any recommendations regarding the use of neck location in predicting PHACE syndrome involvement, and practitioners should focus on other statistically significant factors in stratifying risk.

Most of the patients were White and female, which is consistent with prior studies5,13 on demographic characteristics of patients with IHs. Because of the low number of patients of other races, these variables were collapsed into 1 group of race other than White. This group still had only 28 patients, more than half of whom were Asian (including the Indian subcontinent). Of 15 Asian patients, 13 had PHACE syndrome. Both this group of races other than White as well as patients of Hispanic ethnicity had a higher risk of PHACE syndrome, suggesting that race and/or ethnicity may play a role in risk. However, because of the small number of patients of races other than White and several with unknown race and ethnicity (Table 1), further studies to examine the role and effect of race and ethnicity are warranted. Factors such as access to care, socioeconomic status, and other health disparities could also have played a role in patient inclusion.

Although PHACE syndrome is a rare disease, the involvement of 13 referral centers allowed a large cohort of patients to be assessed. Although retrospective in nature, we believe the strict inclusion criteria regarding clear identification of IH location and full MRI and MRA of the head and neck add validity to this analysis. A minimum number of patients evaluated for PHACE syndrome per year per site was also required to decrease potential bias involving centers that may have infrequently or inconsistently applied a PHACE syndrome evaluation protocol.

The most recently updated 2016 diagnostic criteria were applied to all patients included in our study.7,14 There was discrepancy regarding PHACE syndrome diagnosis for 21 cases between the determination by the original practitioner and strict application of the 2016 criteria (16 changed from no PHACE syndrome to definite and 5 changed from no PHACE syndrome to possible). The risk of PHACE syndrome in patients with large facial IHs observed in the current study was slightly higher than the original prospective study4 but lower than a more recent retrospective study11 performed in the United Kingdom, which estimated a risk of 58%. We hypothesize that differences in referral patterns and health care systems as well as the change in diagnostic criteria may account for these discrepancies in rates.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Because of the retrospective nature, it was not possible to account for the patients with IHs who may have had PHACE syndrome but did not receive a full workup if perceived as being low risk (eg, S2 or parotid involvement). The true risk of PHACE syndrome for various IH characteristics cannot truly be known without prospective data for all patients with large facial IHs regardless of perceived risk. The lack of documented echocardiography results in 21 patients (9%) and eye examination results in 42 patients (18%) may have resulted in a slight underestimation of the incidence of PHACE syndrome. Any underestimate is likely quite small because MRI and MRA are the most likely studies to identify an abnormality diagnostic of PHACE syndrome that would not otherwise be identified on a regular physical examination, which includes heart rate and blood pressure. Patients with only scalp or neck IHs may not have undergone PHACE syndrome evaluation before the newer diagnostic criteria, limiting their numbers and our ability to speculate regarding any associations that involved patterning or risk. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, some patients were missing data points that were not recorded (ie, birth weight, gestational age, race, and ethnicity). Race and ethnicity data entered into the medical record may not match the race and ethnicity that patients identify with. Information on potential confounding factors, including unanticipated factors, may not have been captured. Estimated sizes were also created using mean facial measurements for infants who were being evaluated for any pediatric dermatology issue. This approach precluded a more detailed risk analysis that could have been performed for IH surface area. In addition, these mean facial measurements might not have been representative of the same population of infants with large facial IHs worked up for PHACE syndrome.

One of the study objectives was to assess whether purely deep parotid IHs were associated with a lower risk of PHACE syndrome. Even within this large cohort of an uncommon condition, only 15 patients had purely deep parotid IHs. Some study sites had already discontinued evaluating patients with these types of IHs during the study period based on personal experience. This discontinuation may have decreased the number of these patients in the current study, limiting the ability to fully evaluate the true risk of PHACE syndrome in isolated deep parotid IHs.

Conclusions

This study identified factors associated with both higher and lower risk of PHACE syndrome. The results suggest that high-risk factors are surface area of 25 cm2 or larger and 3 or more segment locations. Involvement of the parotid gland and S2 segment was associated with lower risk of PHACE syndrome. None of the characteristics examined were associated with no risk. More studies are needed to better delineate the association of PHACE syndrome with race and ethnicity. This knowledge can guide practitioners in evaluation and treatment of these patients.

eTable 1. Additional Information on PHACE Patients With Presumed “Low Risk” IH (Isolated S2 IH or Isolated Deep Parotid IH)

eTable 2. Number of Patients Diagnosed With PHACE Meeting Individual Relevant Major and Minor Criteria

eFigure 1. Facial Measurements of Consecutive Infants Between 3 Weeks and 3 Months of Age Seen in the Pediatric Dermatology Clinic

References

- 1.Frieden IJ, Reese V, Cohen D. PHACE syndrome. the association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(3):307-311. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1996.03890270083012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner JE, McCoy GN, Hess CP, et al. Structural malformations of the brain, eye, and pituitary gland in PHACE syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(1):48-55. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosig CL, Siegel DH, Haggstrom AN, Frieden IJ, Drolet BA. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with PHACE syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(4):415-423. doi: 10.1111/pde.12870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haggstrom AN, Garzon MC, Baselga E, et al. Risk for PHACE syndrome in infants with large facial hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):e418-e426. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggstrom AN, Lammer EJ, Schneider RA, Marcucio R, Frieden IJ. Patterns of infantile hemangiomas: new clues to hemangioma pathogenesis and embryonic facial development. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):698-703. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haggstrom A, Endicott A, Chamlin S, et al. Mapping of segmental and partial segmental hemangiomas of the face and scalp. Abstract presented at: International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies Online Workshop; May 14-15, 2020; virtual presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garzon MC, Epstein LG, Heyer GL, et al. PHACE syndrome: consensus-derived diagnosis and care recommendations. J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.07.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen GM, Hansen LM, Stefanko NS, et al. Evaluating the safety of oral propranolol therapy in patients with PHACE syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(2):186-190. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SmartTots.org. Consensus statement on the use of anesthetic and sedative drugs in infants and toddlers. Published October 2015. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://smarttots.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/ConsensusStatement V10-10.2017.pdf

- 10.Blumfield E, Swenson DW, Iyer RS, Stanescu AL. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: review of recent literature on magnetic resonance imaging signal intensity changes and tissue deposits, with emphasis on pediatric patients. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(4):448-457. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4304-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forde KM, Glover MT, Chong WK, Kinsler VA. Segmental hemangioma of the head and neck: high prevalence of PHACE syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):356-358. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youssef MJ, Siegel DH, Chiu YE, Drolet BA, Hodgson BD. Dental root abnormalities in four children with PHACE syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(4):505-508. doi: 10.1111/pde.13818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drolet BA, Esterly NB, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas in children. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):173-181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metry D, Heyer G, Hess C, et al. ; PHACE Syndrome Research Conference . Consensus statement on diagnostic criteria for PHACE syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1447-1456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Additional Information on PHACE Patients With Presumed “Low Risk” IH (Isolated S2 IH or Isolated Deep Parotid IH)

eTable 2. Number of Patients Diagnosed With PHACE Meeting Individual Relevant Major and Minor Criteria

eFigure 1. Facial Measurements of Consecutive Infants Between 3 Weeks and 3 Months of Age Seen in the Pediatric Dermatology Clinic