Summary

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease characterized by significant vascular alterations and multi‐organ fibrosis. Microvascular alterations are the first event of SSc and injured endothelial cells (ECs) may transdifferentiate towards myofibroblasts, the cells responsible for fibrosis and collagen deposition. This process is identified as endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EndMT), and understanding of its development is pivotal to identify early pathogenetic events and new therapeutic targets for SSc. In this review, we have highlighted the molecular mechanisms of EndMT and summarize the evidence of the role played by EndMT during the development of progressive fibrosis in SSc, also exploring the possible therapeutic role of its inhibition.

Keywords: endothelial cells, endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition, systemic sclerosis

During Systemic Sclerosis (SSc), the alteration of endothelial cells (ECs) functions plays a pivotal role during vascular remodelling, playing as trigger for fibroproliferative disorder. After pathological stimuli, such as TGF‐β, ET‐1, TNF‐α, IL‐1, INF, hypoxia, ROS and miRs, ECs may trans‐differentiate toward myofibroblasts, through the endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EndMT), losing vascular ECs markers, gaining mesenchymal cell markers and invading the surrounding tissue. A better understanding of EndMT mechanisms is pivotal, to identify clinically useful biomarkers, in order to develop effective anti‐fibrotic therapies during SSc, a condition in which an appropriated therapy is still lacking.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease, characterized by vascular disorder and progressive tissue fibrosis [1]. Recently, a systematic review emphasized the evidence that, during SSc, endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction is the pivotal event contributing to SSc vasculopathy [2]. Much work has confirmed that injured microvascular cells may transdifferentiate towards myofibroblasts, the cells responsible for fibrosis and collagen deposition in the affected tissues [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. In‐vivo animal models, in which collagen‐producing cells have been tracked, showed that pericytes may differentiate to myofibroblasts, as shown during the development of kidney fibrosis [11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. With regard to ECs, several reports [4, 16, 17] have confirmed the ability of these cells to transdifferentiate towards myofibroblasts through the endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EndMT), which is a non‐malignant phenomenon of cellular transdifferentiation by which ECs undergo a phonotypical differentiation, losing vascular ECs markers and gaining mesenchymal cell markers [2, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. EndMT was first reported in studies on the physiological development of the heart [18, 23] but, to date, this process is considered as a possible pathogenetic mechanism for different conditions, including cardiac fibrosis, kidney fibrosis, diabetic nephropathy, pulmonary hypertension and SSc [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. Understanding the mechanism and functions of the EndMT process is pivotal to individuate early pathogenetic events and possibly new therapeutic targets for SSc in a very early phase, before the fibrotic process, which may be considered an end‐stage condition [10, 30, 31]. In this review, we highlight the molecular mechanisms of EndMT and summarize the evidence on the role of EndMT in SSc fibrosis. Although EndMT is now considered to be the first step leading to the fibrotic processes of many diseases [18], its role in the pathogenesis of SSc vasculopathy still needs further clarification. The possibility to more clearly identify the mechanistic steps and the related molecules of EndMT in SSc will allow us to develop new therapeutic perspectives for fibrosis in SSc, a condition for which an appropriate therapy is still lacking.

Methods

We designed a comprehensive search of literature on EndMT in SSc because this process plays an important role in the pathogenesis of SSc, linking the two main aspects of the disease, such as vasculopathy and fibrosis, by a review of reports published in indexed international journals until 31 December 2020. We followed the proposed guidelines for preparing a biomedical narrative review [32]. MedLine (via PubMed) and Embase databases were searched. The bibliography of relevant articles was also hand‐searched for identification of other potentially suitable studies.

The EndMT process

The EndMT process is an embryonic physiological method observed in 1975, during the development of heart valves in vertebrate embryos. In this pioneering study, the authors reported that, at day 9 of embryo life, the endocardial cells from the atrioventricular canal and the efferent tract showed cellular hypertrophy, lateralization of the Golgi apparatus, formation of cellular appendages and loss of cell polarity [23]. This observation was further confirmed in chicken embryos, where the ECs derived from the heart underwent morphological transdifferentiation, with activation of migratory phenotype and expression of α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) [33].

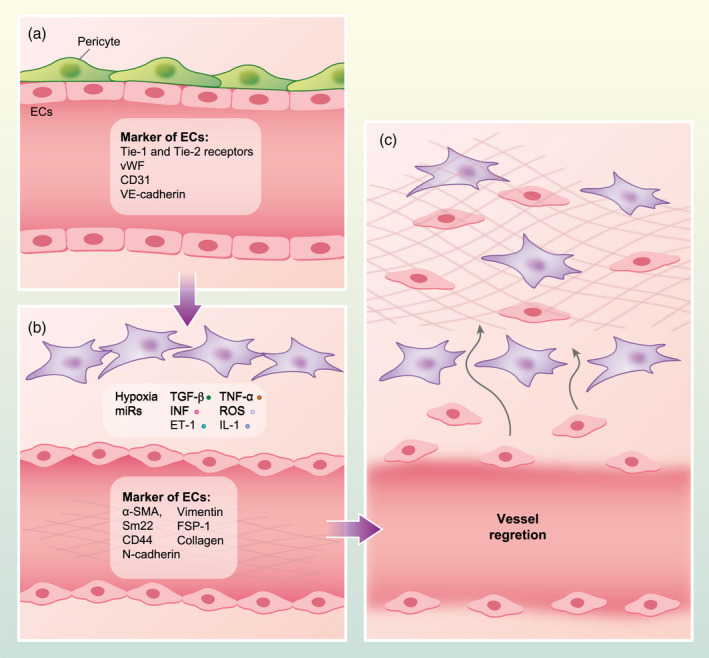

Molecularly, the EC ‘mesenchymal’ phenotype is characterized by the loss of both junctions among cells and EC markers, such as von Willebrand Factor (vWF), CD31, Tie‐1 and Tie‐2 receptors and vascular endothelial‐cadherin (VE‐cadherin), as well as acquisition of the expression of mesenchymal markers such as α‐SMA, smooth muscle 22 (Sm22), CD44, neuronal‐(N‐)cadherin, vimentin, fibroblast‐specific protein‐1 (FSP 1) (S100A4) and collagen [18, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Furthermore, ECs lose their typical cobblestone morphology, acquiring the phenotype and proliferative ability typical of mesenchymal cells, but diminishing barrier skill [39, 40, 41]. During EndMT, the vessel lining is impaired due to disaggregation of ECs from the vessel layer and EC invasion of the surrounding tissue [42, 43, 44, 45] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Outline of the endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EndMT) process. (a) In physiological conditions, endothelial cells (ECs) express von Willebrand factor (vWF), Tie‐1 and Tie‐2 receptors, CD31 and vascular endothelial‐cadherin (VE‐cadherin), displaying cobblestone morphology and surrounded by pericytes. (b) After pathological stimuli, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β, endothelin‐1 (ET‐1), tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin (IL)‐1, interferon (IFN), hypoxia, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and microRNAs (miRs), ECs acquire invasive properties and express mesenchymal markers such as α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA), smooth muscle 22 (Sm22), CD44, N‐cadherin, vimentin and fibroblast‐specific protein‐1 (FSP‐1) (S100A4) and collagen. In these conditions, ECs show the typical elongated shape of mesenchymal cells and, together with surrounding pericytes, may transdifferentiate toward myofibroblasts. (c) ECs, differentiated towards mesenchymal cells, increase their migratory and proliferative capacity, losing their barrier skill. During EndMT, resident ECs disaggregate from the organized cells layer of the vessel walls and invade the surrounding tissue. In this phase, the transdifferentiated cells may release collagen in the tissue, contributing to fibrosis.

The EndMT process was observed not only during physiological development [24, 46] and wound healing [47], but also during pathological processes, characterized by fibrosis, vascular injury and inflammation [24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. The use of lineage tracing models, assessing the EndMT in vivo, confirmed the EC lineage conversion [48]. This strategy has been successfully employed to show the EndMT process in several diseases, including cardiac [18] and kidney [49, 50] fibrosis, vein graft remodelling [51] and cancer [18].

Microvascular damage and remodelling in SSc

Vascular alterations and remodelling are a pivotal event of SSc, observed in different affected organs, including lung, heart, skin and kidney [34, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57]. At present, the SSc vasculopathy, including pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), heart involvement and scleroderma renal crisis, is the main cause of disease‐related mortality [58]. Small‐ and medium‐sized arteries may undergo intimal hyperplasia, medial thickening, obliteration of the lumen, perivascular inflammation and microthrombi [58, 59]. Additionally, in the early stages of SSc, the capillary are often enlarged and thinned during the later phases. Despite the persistent hypoxia observed after the loss of the microvasculature during SSc, compensatory angiogenesis did not occur [60]. Hypoxia promotes the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor (TGF‐β), both promoting the EC activation and their transdiffferentiation towards mesenchymal cells, thus leading to fibrosis [58]. It must be noted that, despite the high levels of VEGF in skin and serum of SSc patients, an impaired angiogenic response persists [61, 62]. This impaired compensatory angiogenesis may be due to an anti‐angiogenic VEGF165b isoform, derived from alternative splicing of VEGF‐A pre‐mRNA, which may be over‐expressed in dermal ECs, fibroblasts and inflammatory cells isolated from SSc patients [63, 64]. Furthermore, it has been shown that platelets may release VEGF165b after activation with the damaged SSc endothelia, probably the main source of this molecule in bloodstream [65, 66].

Recently, our group showed that the deficit in compensatory angiogenesis observed in SSc patients may be related to impaired endothelium–perivascular cell cross‐talk. We have reported that the maintenance and the stabilization of the new vessel is regulated by the cross‐talk between ECs and pericytes via the release of both cytokines and growth factors [13]. This homeostasis is altered during SSc: after injury, the SSc‐ECs release TGF‐β and platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF‐BB) and these molecules promote pericyte proliferation and transdiffferentiation towards myofibroblasts, thus leading to fibrosis. Additionally, the increased expression of VEGFR receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2) on pericytes may inhibit PDGF receptor (PDGFR) signalling through the induction of VEGFR‐2/PDGFR complexes, interfering with vessel stabilization and leading to vascular regression [13].

Approach to operations in patients with SSc

SSc patient management during perioperative phases is an important challenge for the clinicians, due to its rare incidence, little evidence‐based guidance and multi‐organ involvement. The extension and the severity of disease should be evaluated during preoperative and anaesthesiological evaluation [67, 68, 69, 70].

Cardiovascular involvement, especially in SSc patients at risk for cardiomyopathy, should be carefully assessed during preoperative phases [71, 72]. During post‐operative vascular implants, including stents, vascular grafts and heart valves, the patients should be monitored because it has been reported that EndMT may be involved in endothelia disfunction leading to in‐stent restenosis. Previous work has shown that substrate stiffness may influence EC behaviour; stronger EndMT was observed when ECs were cultured on stiffer film [73, 74]. Furthermore, conflicting results have been reported concerning the use of silicone, a synthetic polymer retained as an inert substance present in several medical products, including breast implants and insurgence of SSc, especially after implant rupture, which has been supposed to activate cell transdiffferentiation [75, 76].

The facial manifestations of SSc are strongly disabling and severely impair the patients’ self‐image, compromising their quality of life [77]. The face of SSc patients is frequently involved by fibrosis leading to aesthetic and functional concerns [78]. Due to skin thickening, fibrosis may lead to microstomia, restricted mouth opening and poor cervical extension [79, 80]. Additionally, during intra‐operative management of the patients, skin thickening may generate a barrier for intravenous access, leading to a low threshold for ultrasound guidance for vascular catheter insertion [81]. Autologous fat tissue grafting, also known as lipofilling, is one of the most common procedures in the area of plastic surgery used to restore the defect of soft tissue. It has recently been reported that autologous fat grafting improves facial scleroderma from both aesthetic and functional aspects, playing a therapeutic role on fibrosis [82, 83]. The effect of fat tissue grafting depends not only upon its volumizing effect, but also upon its regenerative/reparative effect, probably for the adipose‐derived stem cell (ASC) content [9, 84, 85]. The regenerative effect of ASC, contained in fat tissue, is due the ability of these cells to transdiffferentiate in situ [86], and probably to control inflammation and angiogenesis, as reported during the early phase of tissue repair in experimental peritoneal fibrosis [87]. At present, further investigation is needed to confirm the possible active role of fat tissue grafting on EndMT in SSc patients.

Mediators involved in EndMT

TGF‐β

TGF‐β is a cytokine involved during development of the embryo, cellular differentiation and inflammation, playing a role in fibrotic disease, promoting the release of collagens and preventing the expression of metalloproteinases [58, 88]. The TGF‐β family is currently considered to be the pivotal inducer of EndMT during development of the heart [89], cancer [90] and SSc. In the latter, TGF‐β is considered to be the main actor in fibrotic process [88, 91]. There are three TGF‐β isoforms which bind to the TGF‐β receptor type II, promoting the activation of TGF receptor type I (the so‐called activin receptor‐like kinases, ALKs), thus activating the cell signals via the SMA‐ and mad‐related (Smad) signal pathway family [34]. Although TGF‐β is the pivotal trigger for EndMT, the type I receptors’ contribution to TGF‐β‐induced EndMT is still unknown. Recently, it has been reported that TGF‐β1 and TGF‐β2 promoted EndMT mediated by an increase of ALK5 expression, associated with a decrease of ALK1, in the presence of N‐cadherin over‐expression and inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [92]. Although all TGF‐β isoforms may induce EndMT, it has been reported that TGF‐β1 is mainly associated with the pathological fibrotic process associated with EndMT, while TGF‐β2 seems to be mainly associated with the physiological EndMT condition, such as embryonic heart development [93]. TGF‐β promotes its profibrotic role, inducing morphological changes in ECs, committing them to a fibrogenic fate and stimulating the transient expression of PDGFR‐α mRNA, resulting in increased expression of the mesenchymal markers associated with a reduced expression of endothelial markers [94, 95, 96].

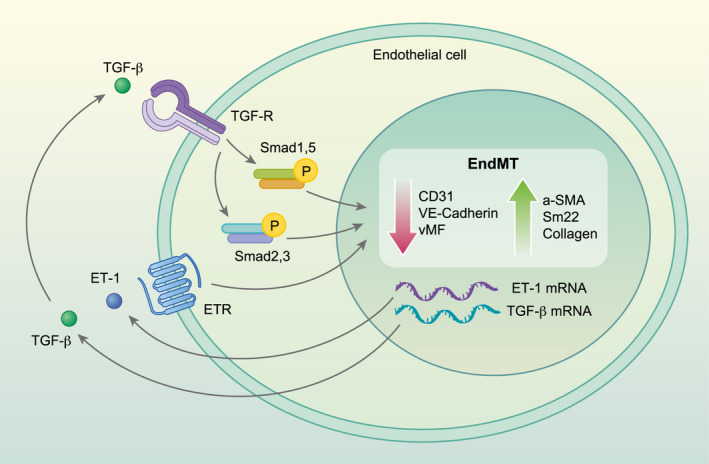

Endothelin‐1 (ET‐1)

ET‐1 is a potent vasoconstrictor and controls the vascular tone, binding both endothelin receptors A (ETRA) and B (ETRB), thus promoting fibrosis, and possibly contributing to the small‐vessel rarefaction observed in SSc patients [97, 98]. Interestingly, it has been reported that, in skin fibroblasts, TGF‐β may promote the transcription of the ET‐1 gene [52, 99], and ET‐1 may increase the de‐novo synthesis and secretion of TGF‐β [34, 100], suggesting that the TGF‐β/ET‐1 axis in these cells may modulate fibrogenic responses [34, 101] (Fig. 2). In fibroblasts, ET‐1 may induce transdiffferentiation towards myofibroblasts, promoting the release of extracellular matrix proteins such as types I and III collagen and fibronectin and the inhibition of metalloproteinase expression [102, 103]. Conversely, in human ECs, ET‐1 may promote increased expression of α‐SMA, as well as increased collagen production, thus modulating the EndoMT [4, 16, 17, 34].

Fig. 2.

Role of endothelin‐1 (ET‐1) and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β during endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EndMT). Both TGF‐β and ET‐1, which are largely over‐expressed in systemic sclerosis (SSc), may promote the decrease of endothelial markers, such as CD31, von Willebrand factor (vWF) and vascular endothelial‐cadherin (VE‐cadherin) and the increase of mesenchymal markers, such as α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA), smooth muscle 22 (Sm22) and collagen (Col1A1). ET‐1 may promote the TGF‐β mRNA transcription which, in turn, further promote ET‐1 mRNA, in a vicious loop. Both these molecules may modulate fibrogenic responses.

Wingless/integrated (Wnt) proteins

The Wnt proteins include a family of glycoproteins, playing a pivotal role in the pathogenic process occurring in fibrotic diseases, including SSc, via canonical and non‐canonical intracellular signalling pathways [104, 105, 106]. TGF‐β activates the canonical Wnt pathway and several genes which are transcriptional targets of Wnt/β‐catenin [107], leading to tissue fibrosis. It has been reported that, in human ECs, Wnt3a may modulate EndMT promoting the expression of cadherin and inhibiting the expression of vimentin [108].

Interleukin (IL)‐1

IL‐1 family consists of 11 pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines. Expression of the principal IL‐1 family cytokines, such as IL‐1α, IL‐1β, IL‐18 and IL‐33, is impaired in several autoimmune diseases, including SSc. Additionally, gene polymorphisms of IL‐1α, IL‐1β, IL‐18 and IL‐33 correlate with SSc susceptibility [109] The involvement of these cytokines during EndMT was first demonstrated via in‐vitro experiments, where human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured with supernatants derived from activated peripheral blood mononuclear leucocytes. In this setting, morphological and phenotypical changes were observed in HUVECs, mirroring the EndMT process and confirming the important role of IL‐1β during this process [110]. IL‐1β acts synergistically with TGF‐β2 to promote the EndMT in HUVECs. ECs, stimulated with both IL‐1β and TGF‐β2, exhibited morphological and phenotypical changes and significantly increased Sm22 expression when compared to cells separately stimulated with IL‐1β or TGF‐β2 [91]. This observation confirmed that IL‐1β and other inflammatory cytokines may be potent stimuli for EndMT [111, 112]. Recently, it has been reported that IL‐1β promotes EndMT in HUVECs via the natural killer (NF)‐κB/Snail pathway and protein tyrosine phosphatase L1 (PTPL1), a non‐receptor‐type protein tyrosine phosphatase, implicated in several signal pathways. The inhibition of PTPL1/NF‐κB signalling may prevent the IL‐1β‐induced EndMT process in HUVECs [113]

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α

TNF‐α is a cytokine mainly released by macrophages, modulating immune response and driving the main cellular response [112]. It has been reported that serum concentrations of TNF‐α are increased in SSc patients and correlate with the onset of pulmonary fibrosis and PAH [114]. Additionally, over‐expression of TNF‐α has been shown to result in severe pulmonary hypertension and emphysema in mice, suggesting that TNF‐α plays a pivotal role in pulmonary vascular physiology, stimulating the progression of the endothelial dysfunction [115]. TNF‐α has been implicated in EC activation following inflammatory events, promoting the expression of adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM‐1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM‐1) [19, 116]. Furthermore, TNF‐α has been implicated in EndMT activation in lymphatic ECs; EndMT‐related miRNAs were over‐expressed in rat mesenteric lymphatic ECs [117]. During the last year it has been reported that EC treatment with TNF‐α stimulates Smad2/3 signals, which are probably promoted by the increased expression of TGF‐β type I receptor, TGF‐β2, activin A and integrin α V. These data suggest that TNF‐α enhances TGF‐β‐induced EndMT by stimulating the TGF‐β signalling pathway [118].

Interferon (IFN)

Another possible mediator of EndMT is the IFN family. It has been reported that IFN‐γ induces the expression of TGF‐β2, ET‐1 and α‐SMA in human microvascular ECs. Furthermore, IFN‐γ may also induce the expression of several genes related to EndMT, including regulator of G protein signalling 2 (RGS2), fibronectin 1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1), TWIST‐related protein 1 (TWIST1), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT‐3), Snail‐1 and genes implicated in Wnt signalling [119]. Saigusa et al. showed that the IRF5 gene, a member of the IFN regulatory factor (IRF) family, may play a critical role in the bleomycin (BLM) SSc murine model, acting as a SSc susceptibility gene. Dermal and pulmonary fibrosis induced by BLM are inhibited in IRF5‐deficient (Irf5−/−) mice. Furthermore, also the classical hallmarks of SSc, such as fibroblast activation, inflammation, EndMT, vascular regression, impaired T helper type 2 (Th2)/Th17 immune polarization and B cell stimulation, are inhibited in this model. On this basis, IRF5 may be involved in EndMT, and suppressing the IRF5 pathways may lead to the inhibition of SSc development [120].

MicroRNA (miR)

New advances for EndMT mediators are represented by miRs. These molecules are small non‐coding RNAs, which are post‐transcriptional repressors of genes [121, 122]. Previous studies have shown the involvement of several miRs (miR‐29s, miR‐125b and 126, miR‐130) in the development of EndMT [42] and the interaction between TGF‐β and several miRs (miR‐21, miR‐31, miR‐155) in modulating EndMT [42]. Of note, the increased expression of miR‐148b stimulates, in ECs, the ability to form vessels, migrate and proliferate, whereas its silencing increases the EndMT after TGF‐β stimulus. [123]. Additionally, the constitutive expression of miR‐31 induces TGF‐β‐induced EndMT in ECs [124] and the up‐regulation of miR‐130a, which is increased in the PAH experimental model, may promote the expression of α‐SMA, a key molecule in the EndMT process [125]. Considering the regulatory effects exerted by miRs on several signalling pathways, these molecules have been extensively studied as potential therapies for a large number of diseases, including cancers and cardiovascular diseases [126, 127, 128]. Concerning cancer diseases, intratumoral injections of miR drugs, such as miR mimics or repressors, may regulate the expression of specific genes decoding for molecules involved in the cancer development, thus enhancing target specificity, efficacy and minimizing side effects [129, 130, 131]. It has been shown that miR‐204 is inhibited by hypoxia in both rat pulmonary arterial intima and human pulmonary artery ECs. When miR‐204 is suppressed using a specific inhibitor the lack of this miR, in the context of hypoxia, leads to enhanced autophagy, a cellular homeostatic process that occurs both under basal and stressful conditions, with subsequent death of ECs and inhibition of hypoxia‐induced EndMT [132]. Recently, it has been reported that miR‐200c‐3p may play a critical role in EndMT. In a model of aortic grafting, miR‐200c‐3p expression is strongly increased, and grafted arteries undergo to neointimal hyperplasia via the EndMT process. Conversely, the inhibition of this miRin grafted arteries is associated with a reduction of neointimal formation [133]. Another important miR is MiR‐181b, which is down‐expressed in rat models of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Its over‐expression, in this model, attenuated the pulmonary vascular hypertrophy, right ventricular remodelling and the EndMT process. Additionally, in primary rat pulmonary arterial ECs, the induction of miR‐181b reversed the EndMT [134]. Also, miR‐92a may be a pivotal regulator in promoting EndMT during vein graft remodelling, Interestingly, in vivo, the inhibition of miR‐92a, by adeno‐associated virus‐mediated gene therapy, decreases EndMT, reducing vein graft neointimal formation and improving graft patency [135]. We may speculate that a clearer understanding of the role of miR during the EndMT observed in SSc and in other diseases may open new therapeutic advances, targeting key molecules of fibrotic disorders [121].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Another mediator of EndMT may be ROS [25, 42]. It has been shown that ROS play an important role in controlling the TGF‐β profibrotic effects via Smad2/Smad3 activation [42, 136, 137, 138]. It has been demonstrated that [25] chronic oxidative stress and abnormal fibrillin‐1 expression may mediate EndMT in Tsk−/+ mice and that reducing the oxidative stress, by administration of oxidized phospholipids scavengers, may decrease both endothelial apoptosis and mesenchymal transition [25]. Furthermore, in models of SSc‐like BLM‐induced fibrosis, this agent induces collagen (I and III) synthesis, mediated by ROS [139]. Anti‐oxidants such as N‐acetyl‐cysteine may attenuate collagen expression in experimental models of BLM‐induced lung fibrosis [140, 141]. Although the latter studies do not explore the effect on EndMT, the reduction of ROS levels is able to inhibit EndMT process, both in vitro and in the lung of rats with pulmonary hypertension [142].

Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)

Hypoxia is another pivotal characteristic of SSc, playing a key role during angiogenesis. Furthermore, hypoxia is a potent promoter of EndMT, mainly in PAH [143] and in radiation‐induced fibrosis [144], via the HIF‐dependent pathways [145]. Furthermore, hypoxia may also regulate the expression of TGF‐β, the main promoter of EndMT [146]. EndMT keys transcription factors, such as Snail [147] and Twist‐1 [148], are also identified as targets of hypoxia. The role of hypoxia and HIF signalling are particularly relevant in SSc angiogenesis [149]. Recently it has been reported that autophagy may mediate both hypoxia‐induced fibroblast collagen synthesis and EndMT in SSc. Hypoxia exposure up‐regulates the expression of collagen I and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in SSc fibroblasts and the expression of EndMT markers in HUVECs. In the same conditions, fibroblasts and HUVECs form more autophagosomes and autolysosomes, suggesting the induction of autophagy [150].

Evidence of EndMT during human SSc

Following the first evidence of the lack of endothelial‐specific marker (VE‐cadherin) in SSc skin [151] our group was able to show that, after ET‐1 and TGF‐β stimulation, SSc‐ECs display a reduction of endothelial markers, including vWF, CD31 and VE‐cadherin, and an up‐regulation of profibrotic markers such as sSm22, α‐SMA and collagen, confirming the induction of the EndMT programme [34].

ECs lining injuries are the early events occurring in patients with SSc [152, 153]. In these patients, arteries are generally impaired and characterized by intimal hyperplasia, medial thickening, obliteration of the lumen and inflammation [58, 154], thus contributing to the vascular remodelling occurring during PAH [155]. It has been reported that EndMT may also play a pivotal role during the PAH pathogenesis, promoting dysfunction of the ECs [156]. Histological assessment of patients with SSc‐associated PAH identifies the presence vWF/α‐SMA‐positive ECs in up to 5% of pulmonary vessels [156]. Furthermore, the exposure of ECs, obtained from the pulmonary artery, to proinflammatory cytokines, including IL‐1β, TNF‐α and TGF‐β, changes their typical cobblestone phenotype and induces the expression of mesenchymal markers [156]. CD31+/CD102+ ECs isolated from SSc lungs expressed at the same time as mesenchymal/EC markers support the evidence of EndMT in lung tissues from SSc patients with ILD [157, 158]. Successively, EndMT is documented in SSc skin [22], showing the increased expression of mesenchymal markers in SSc‐ECs when compared with healthy controls (HC). Taken together, these data confirm the evidence of the EndMT programme in all the affected tissues and indicate the important pathogenic role of this mechanism during this disease.

Recently, in an experimental model of SSc, the double heterozygous mice for Klf5 and Fli1 (Klf5+/−; Fli1+/−), showing the three main pathological characteristics of SSc [159], the dermal microvascular ECs isolated from these mice, show defective angiogenesis and reduced expression of VE‐cadherin and CD31, confirming the evidence of EndMT in this SSc model [160].

As previously discussed, the exposition to several local biological mediators, such as TGF‐β, PDGF, VEGF and ET‐1 [42], activates the ECs and modulates the expression of adhesion molecules on the EC surface [161, 162], thus promoting the recruitment activated T and B lymphocytes and profibrotic macrophages. Following recruitment, inflammatory cells release profibrotic growth factors such as TGF‐β and CTGF in the tissue. Under the effect of these growth factors, ECs release ET‐1, activating EndMT [163, 164]. Furthermore, increased levels of the IL‐6 family, such as oncostatin M (OSM) and IL‐6, have been shown in many pathological diseases, characterized by inflammation, vasculopathy and fibrosis, including SSc [165]. Recently, it has been reported that, in dermal SSc‐ECs, the treatments with OSM or IL‐6+sIL‐6R stimulate proinflammatory genes, together with genes related to EndMT [166]. The serum levels of the leucotriene (LT) B4, an inflammatory lipid mediator, are increased in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc and ILD and promote EndMT via the phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, independently of TGF‐β release [167].

Macrophages are both a player and a target in SSc [147]. These cells play an important role in the innate response [168, 169, 170, 171], although conflicting results are present in the available literature. Alternatively, activated macrophages (M2) prompt precursor transdiffferentiation towards myofibroblasts. These macrophages are present in the perivascular area of the tissues of patients with SSc, supporting fibrosis [172, 173, 174]. Moreover, some authors have shown that these macrophages may influence the function and molecular repertoire of ECs, inhibiting EndMT and preventing fibrosis, in a model of muscle repair after sterile injury [175]. Successively, their inhibiting role has been confirmed by lineage‐tracing transgenic mice models, in which endothelial‐derived cells (EdCs) transdiffferentiate towards mesenchymal cells after treatment with BLM. EdCs retrieved from the lung show a significant inhibition of endothelial markers and an increase of mesenchymal markers. This effect is counterbalanced by macrophages, which preserve the endothelial morphology of EdCs. Finally, the EndMT was activated after macrophage depletion [176].

Targeting EndMT

Due to the importance of EndMT in the pathogenic steps of many diseases, several drugs have been assessed in experimental models as potential EndMT inhibitors.

Conflicting results have been reported concerning rapamycin, an inhibitor of the mTOR signalling pathway, which plays a key role in TGF‐β‐mediated EndMT [159, 177, 178, 179]. It has been shown that this drug may prevent EndMT by suppressing the EC ability to migrate and to degrade the extracellular matrix [180]. It has been reported that in mice undergoing peritoneal dialysis the treatment with rapamycin reduces the peritoneal membrane thickness and EndMT process, suggesting that rapamycin has a protective effect on peritoneal membrane during peritoneal dialysis through an anti‐fibrotic and anti‐proliferative effect [181]. Moreover, it has been recently reported that, although rapamycin is able to suppress the senescence‐associated phenotype in human coronary artery ECs, treatment with rapamycin in this model may promote EndMT through the activation of autophagy [182].

Tanshinone IIA (Tan IIA), a phytochemical drug, plays an anti‐fibrotic effect, ameliorating skin thickness and collagen deposition, in the BLM‐treated SSc mouse model. Tan IIA contrasts the inhibition of angiogenesis promoted by BLM probably interfering with the induction of the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway, which seems to be implicated in vascular damage of the BLM‐treated SSc mouse model [159, 177, 183, 184].

Geniposide, an iridoid glycoside, has been shown to inhibit the EndMT in the BLM‐induced scleroderma experimental model via the suppression of the mTOR signalling. On this basis, it is possible to speculate that geniposide may be a new potential therapeutic candidate to prevent vascular damage in SSc patients [185].

Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the PDGF receptor, which is the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia [186], has been shown to relieve EndMT in experimental models of PAH, induced by hypoxia, suggesting its potential therapeutic use [187, 188]. Recently, another tyrosine kinase inhibitor of PDGF and VEGF, nintedanib, is able to improve PAH by inhibiting EndMT. Nintedanib attenuates the expression of mesenchymal markers in human pulmonary microvascular ECs and the proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, suggesting that this molecule might be another new therapeutic treatment for PAH, preventing vascular remodelling [189].

Among the EndMT mediators, TGF‐β is the principal molecule involved, and inhibiting TGF‐β may be a potential therapeutic approach. Spironolactone, an aldosterone receptor‐blocker, significantly inhibits EndMT induced via TGF‐β, down‐regulating vimentin, up‐regulating CD31 in HUVECs as well as inhibiting cell migration during EndMT, via the block of TGF‐β and Notch signalling [190]. Another TGF‐β inhibitor, the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitor linagliptin, may block TGF‐β2‐induced EndMT, interfering with TGF‐β/integrin‐β1 interaction [191]. Arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD) is an Arg‐Gly‐Asp tripeptide motif, implicated in cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix. It has been reported that the RGD antagonist may revert TGF‐β1‐induced EndMT and consequently may be potentially used as an anti‐fibrotic therapeutic approach [192]. Glycyrrhizin, clinically used for chronic hepatic diseases and itching dermatitis, improves dermal fibrosis and EndMT in BLM‐treated mice, interfering with TGF‐β signalling in dermal fibroblasts via thrombospondin‐1 down‐regulation [193]. Another TGF‐β signalling inhibitor is AdipoRon, a novel orally active small molecule selective for adiponectin receptors. It has been shown that adiponectin exerts its protective role in preclinical models of cardiac, pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis, interfering with TGF‐β signalling. It has been shown that chronic administration of AdipoRon significantly improves BLM‐induced dermal fibrosis in mice, attenuating fibroblast proliferation, adipocyte‐to‐myofbroblast transdifferentiation, Th2/Th17 polarization, vascular regression and EndMT within the affected skin. These results suggest that AdipoRon plays a protective role in microvascular damage induced by the treatment with BLM, preventing EndMT and vessel regression [194]. Additionally, treatment with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) significantly prevents the occurrence of TGF‐β1‐induced EndMT in HUVECs via blocking Notch signalling [37, 195, 196].

Tamibarotene (Am80) is a synthetic retinoid, able to control the pathological events of several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. It has been shown that this molecule significantly attenuates dermal and hypodermal fibrosis as well as EndMT, ICAM‐1 expression in ECs, infiltration of macrophages, mast cells and lymphocytes and M2 macrophage differentiation in BLM‐treated mice [197].

Interestingly, in previous work [52] we reported that macitentan, an ET‐1 receptor antagonist in vitro, inhibits both ET‐1‐ and TGF‐β‐induced EndMT in microvascular ECs isolated from HC and SSc patients [34, 52]. This effect is mediated by the TGF‐β receptors/ET receptor heterodimer complex expressed on the cell surface, which may be activated by both ET‐1 on the TGF‐β, thus leading to the profibrotic programme and probably inhibited by the ET‐1 antagonist [52]. Successively, these results were confirmed by Corallo et al. [198] using both macitentan and bosentan, another ET‐1 receptor antagonist, in the fibroblast and ECs co‐culture model [198]. These findings suggest that EndMT may be a reversible mechanism, opening a new therapeutic perspective for fibrotic diseases [199, 200, 201].

A decreased expression of the junctions between ECs seems to be a pivotal aspect of EndMT. In blood vessels, ECs form a lining that separates blood from the surrounding tissue. During EndMT ECs lose their cell adhesion, lose their ability to form a barrier and detach from the endothelial monolayer [202]. It has been reported that the adherens junctions, such VE‐cadherin and β‐catenin, are disconnected from the cell membranes, contributing to vasculopathy and EndMT. Interestingly, iloprost, a synthetic analogue of prostacyclin (PGI2), may promote VE‐cadherin clustering at adherens junctions, preventing their loss from the ECs membrane [203, 204]. Recently, Tsou et al. showed that iloprost promotes the stabilization of adherens junctions, promotes angiogenesis and prevents EndMT, all these activities having important therapeutic benefits in SSc [205].

Recently, it has been reported that paeoniflori (PF), a monoterpene glycoside with endothelial protection, vasodilation, anti‐fibrotic, anti‐inflammatory and anti‐oxidative properties, significantly prevents chronic hypoxia/SU5416‐induced PAH in rats and its therapeutic effect seems to be related to its ability to inhibit EndMT in pulmonary arterial ECs [206].

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

During SSc, dysregulation of EC functions plays a pivotal role during vascular remodelling, acting as trigger for fibroproliferative disorder [2, 207, 208]. The transdiffferentiation of injured ECs towards a myofibroblastic phenotype plays an important role in SSc pathogenesis, this process being the link between vascular activation and fibrotic process [4, 34, 52]. A clearer understanding of the processes responsible for EndMT is of primary importance to recognize clinically useful biomarkers in order to predict fibrotic remodelling, and/or to develop effective anti‐fibrotic therapies in different fibrotic conditions. To date, many EndMT inhibitors are available, and exploring their efficacy in SSc may be an important challenge, considering that, to date, no disease‐modifying agents are still available.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition and interpretation of literature. All authors contributed to the critical review and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. P. D. B. and P. R.: study conception and design, literature search, figure creation, writing, paper revision and acceptance; O. B., M. V., L. N. and V. D.: literature search, writing, paper revision and acceptance; P. C., R. G.: study conception and design, writing, paper revision and acceptance.

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for this study. The authors thank Mrs Federica Sensini for her technical assistance.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1. Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017; 7:1685–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mostmans Y, Cutolo M, Giddelo C et al. The role of endothelial cells in the vasculopathy of systemic sclerosis: A systematic review. Autoimmun Rev 2017; 16:774–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ebmeier S, Horsley V. Origin of fibrosing cells in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015; 27:555–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jimenez SA. Role of endothelial to mesenchymal transition in the pathogenesis of the vascular alterations in systemic sclerosis. ISRN Rheumatol 2013; 2013:835948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Liakouli V et al. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from scleroderma patients (SSc) preserve their immunomodulatory properties although senescent and normally induce T regulatory cells (Tregs) with a functional phenotype: implications for cellular‐based therapy. Clin Exp Immunol 2013; 173:195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jinnin M. ‘Narrow‐sense’ and ‘broad‐sense’ vascular abnormalities of systemic sclerosis. Immunol Med 2020; 43:107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Benedetto P, Liakouli V, Ruscitti P et al. Blocking CD248 molecules in perivascular stromal cells of patients with systemic sclerosis strongly inhibits their differentiation toward myofibroblasts and proliferation: a new potential target for antifibrotic therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 2018; 20:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cutolo M, Soldano S, Smith V. Pathophysiology of systemic sclerosis: current understanding and new insights. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019; 15:753–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P, Cipriani P et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in systemic sclerosis: challenges and perspectives. Autoimmun Rev 2020; 19:102662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P, Liakouli V et al. The vessels contribute to fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Isr Med Assoc J 2019; 21:471–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kida Y, Duffield JS. Pivotal role of pericytes in kidney fibrosis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2011; 38:467–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P et al. Perivascular cells in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis overexpress activated ADAM12 and are involved in myofibroblast transdifferentiation and development of fibrosis. J Rheumatol 2016; 43:1340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P et al. Impaired endothelium–mesenchymal stem cells cross‐talk in systemic sclerosis: a link between vascular and fibrotic features. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16:442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Humphreys BD, Lin S‐L, Kobayashi A et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2010; 176:85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duffield JS. The elusive source of myofibroblasts: problem solved? Nat Med 2012; 18:1178–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frid MG, Kale VA, Stenmark KR. Mature vascular endothelium can give rise to smooth muscle cells via endothelial–mesenchymal transdifferentiation: in vitro analysis. Circ Res 2002; 90:1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arciniegas E, Sutton AB, Allen TD et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 promotes the differentiation of endothelial cells into smooth muscle‐like cells in vitro . J Cell Sci 1992; 103:521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M et al. Endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med 2007; 13:952–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaudhuri V, Zhou L, Karasek M. Inflammatory cytokines induce the transformation of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells into myofibroblasts: a potential role in skin fibrogenesis. J Cutan Pathol 2007; 34:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arciniegas E, Frid MG, Douglas IS et al. Perspectives on endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition: potential contribution to vascular remodeling in chronic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 293:L1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Asano Y, Sato S. Vasculopathy in scleroderma. Semin Immunopathol 2015; 37:489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Manetti M, Romano E, Rosa I et al. Endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition contributes to endothelial dysfunction and dermal fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76:924–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Markwald RR, Fitzharris TP, Smith WNA. Structural analysis of endocardial cytodifferentiation. Dev Biol 1975; 42:160–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li J, Bertram JF. Review: Endothelial–myofibroblast transition, a new player in diabetic renal fibrosis. Nephrology 2010; 15:507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu H, Zaidi M, Struve J et al. Abnormal fibrillin‐1 expression and chronic oxidative stress mediate endothelial mesenchymal transition in a murine model of systemic sclerosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011; 300:C550–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kizu A, Medici D, Kalluri R. Endothelial–mesenchymal transition as a novel mechanism for generating myofibroblasts during diabetic nephropathy. Am J Pathol 2009; 175:1371–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yun E, Kook Y, Yoo KH et al. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition in pulmonary vascular diseases. Biomedicines 2020; 8:639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y, Dong Y, Xiong Z et al. Sirt6‐mediated endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition contributes toward diabetic cardiomyopathy via the Notch1 signaling pathway. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2020; 13:4801–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li C, Kuemmerle JF. The fate of myofibroblasts during the development of fibrosis in Crohn’s disease. J Dig Dis 2020; 21:326–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cipriani P, Marrelli A, Liakouli V et al. Cellular players in angiogenesis during the course of systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev 2011; 10:641–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cipriani P, Marrelli A, Benedetto PD et al. Scleroderma mesenchymal stem cells display a different phenotype from healthy controls; implications for regenerative medicine. Angiogenesis 2013; 16:595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H et al. Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int 2011; 31:1409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakajima Y, Mironov V, Yamagishi T et al. Expression of smooth muscle alpha‐actin in mesenchymal cells during formation of avian endocardial cushion tissue: a role for transforming growth factor β3. Dev Dyn 1997; 209:296–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P et al. The endothelial‐mesenchymal transition in systemic sclerosis is induced by endothelin‐1 and transforming growth factor‐β and may be blocked by macitentan, a dual endothelin‐1 receptor antagonist. J Rheumatol 2015; 42:1808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zeisberg EM, Potenta S, Xie L et al. Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma‐associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res 2007; 67:10123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin F, Wang N, Zhang TC. The role of endothelial–mesenchymal transition in development and pathological process. IUBMB Life 2012; 64:717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clere N, Renault S, Corre I. Endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020; 14:747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Piera‐Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition: role in physiology and in the pathogenesis of human diseases. Physiol Rev 2019; 99:1281–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen PY, Schwartz MA, Simons M. Endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020; 7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kovacic JC, Dimmeler S, Harvey RP et al. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition in cardiovascular disease: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73:190–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dejana E, Hirschi KK, Simons M. The molecular basis of endothelial cell plasticity. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thuan DTB, Zayed H, Eid AH et al. Potential link between oxidative stress and endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in systemic sclerosis. Front Immunol 2018; 19:1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Welch‐Reardon KM, Wu N, Hughes CC. A role for partial endothelial mesenchymal transitions in angiogenesis? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015; 35:303–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van Meeteren LA, Ten Dijke P. Regulation of endothelial cell plasticity by TGF‐β. Cell Tiss Res 2012; 347:177–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin F, Wang N, Zhang T‐C. The role of endothelial–mesenchymal transition in development and pathological process. IUBMB Life 2012; 64:717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lu C‐C, Liu M‐M, Clinton M et al. Developmental pathways and endothelial to mesenchymal transition in canine myxomatous mitral valve disease. Veterinary J 2015; 206:377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee JG, Kay EP. FGF‐2‐mediated signal transduction during endothelial mesenchymal transformation in corneal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res 2006; 83:1309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li Y, Lui KO, Zhou B. Reassessing endothelial‐to mesenchymal transition in cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018; 15:445–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zeisberg EM, Potenta SP, Sugimoto H et al. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19:2282–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xavier S, Vasko R, Matsumoto K et al. Curtailing endothelial TGF‐β signaling is sufficient to reduce endothelial–mesenchymal transition and fibrosis in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26:817–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cooley BC, Nevado J, Mellad J et al. TGF‐β signaling mediates endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EndMT) during vein graft remodelling. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:227ra34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P et al. Macitentan inhibits the transforming growth factor‐β profibrotic action, blocking the signaling mediated by the ETR/TβRI complex in systemic sclerosis dermal fibroblasts. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Altorok N, Wang Y, Kahaleh B. Endothelial dysfunction in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014; 26:615–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Giacomelli R, Liakouli V, Berardicurti O et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: current and future treatment. Rheumatol Int 2017; 37:853–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woodworth TG, Suliman YA, Li W et al. Scleroderma renal crisis and renal involvement in systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018; 14:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P, Liakouli V et al. Linking myofibroblast generation and microvascular alteration: The role of CD248 from pathogenesis to therapeutic target (Review). Mol Med Rep 2019; 20:1488–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ota Y, Kuwana M. Endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Eur J Rheumatol 2020; 7:S139–S146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nicolosi PA, Tombetti E, Maugeri N et al. Vascular remodelling and mesenchymal transition in systemic sclerosis. Stem Cells Int 2016; 2016:4636859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brown M, O'Reilly S. The immunopathogenesis of fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2019; 195:310–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rosa I, Romano E, Fioretto BS et al. The contribution of mesenchymal transitions to the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Eur J Rheumatol 2020; 7:S157–S164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Distler O, Distler JHW, Scheid A et al. Uncontrolled expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors leads to insufficient skin angiogenesis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Circ Res 2004; 95:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cantatore FP, Maruotti N, Corrado A et al. Angiogenesis dysregulation in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Biomed Res Int 2017; 2017:5345673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Manetti M, Guiducci S, Romano E et al. Overexpression of VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, leads to insufficient angiogenesis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Circ Res 2011; 109:e14–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Manetti M, Guiducci S, Romano E et al. Increased plasma levels of the VEGF165b splice variant are associated with the severity of nailfold capillary loss in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72:1425–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hirigoyen D, Burgos PI, Mezzano V et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis by platelets in systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Qiu Y, Hoareau‐Aveilla C, Oltean S et al. The anti‐angiogenic isoforms of VEGF in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans 2009; 37:1207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carr ZJ, Klick J, McDowell BJ et al. An update on systemic sclerosis and its perioperative management. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 2020; 29:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Katsumoto TR, Whitfield ML, Connolly MK. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2011; 6:509–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Herrick AL. Neurological involvement in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34:1007–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Amaral TN, Peres FA, Lapa AT, Marques‐Neto JF, Appenzeller S. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013; 43:335–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Luo Y, Jiang C, Krittanawong C et al. Systemic sclerosis and the risk of perioperative major adverse cardiovascular events for inpatient non‐cardiac surgery. Int J Rheum Dis 2019; 22:1023–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nokes BT, Raza HA, Cartin‐Ceba R et al. Individuals with scleroderma may have increased risk of sleep‐disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med 2019; 15:1665–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhang H, Chang H, Wang LM et al. Effect of polyelectrolyte film stiffness on endothelial cells during endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition. Biomacromol 2015; 16:3584–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhong A, Mirzaei Z, Simmons CA. The roles of matrix stiffness and ß‐catenin signaling in endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition of aortic valve endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Eng Technol 2018; 9:158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lidar M, Agmon‐Levin N, Langevitz P, Shoenfeld Y. Silicone and scleroderma revisited. Lupus 2012; 21:121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Englert H, Morris D, March L. Scleroderma and silicone gel breast prostheses – the Sydney study revisited. Aust NZ J Med 1996; 26:349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Albilia JB, Lam DK, Blanas N et al. Small mouths… big problems? A review of scleroderma and its oral health implications. J Can Dent Assoc 2007; 73:831–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Panchbhai A, Pawar S, Barad A et al. Review of orofacial considerations of systemic sclerosis or scleroderma with report of analysis of 3 cases. Ind J Dentistry 2016; 7:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Shionoya Y, Kamiga H, Tsujimoto G et al. Anesthetic management of a patient with systemic sclerosis and microstomia. Anesth Prog 2020; 67:28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sallam H, McNearney TA, Chen JD. Systematic review: pathophysiology and management of gastrointestinal dysmotility in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 23:691–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. D’Angelo R, Miller R. Pregnancy complicated by severe preeclampsia and thrombocytopenia in a patient with scleroderma. Anesth Analg 1997; 85:839–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Strong AL, Adidharma W, Brown OH et al. Fat grafting subjectively improves facial skin elasticity and hand function of scleroderma patients. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021; 25:e3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gheisari M, Ahmadzadeh A, Nobari N et al. Autologous fat grafting in the treatment of facial scleroderma. Dermatol Res Pract 2018; 1:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Magalon G, Daumas A, Sautereau N et al. Regenerative approach to scleroderma with fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg 2015; 42:353–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Del Papa N, Caviggioli F, Sambataro D et al. Autologous fat grafting in the treatment of fibrotic perioral changes in patients with systemic sclerosis. Cell Transplant 2015; 24:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Guillaume‐Jugnot P, Daumas A, Magalon J et al. State of the art. Autologous fat graft and adipose tissue‐derived stromal vascular fraction injection for hand therapy in systemic sclerosis patients. Curr Res Transl Med 2016; 64:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wakabayashi K, Hamada C, Kanda R et al. Adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells transplantation facilitate experimental peritoneal fibrosis repair by suppressing epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. J Nephrol 2014; 27:507–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lafyatis R. Transforming growth factor β – at the centre of systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014; 10:706–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Garside VC, Chang AC, Karsan A et al. Co‐ordinating Notch, BMP, and TGF‐beta signaling during heart valve development. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013; 70:2899–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Principe DR, Doll JA, Bauer J et al. TGF‐beta: duality of function between tumor prevention and carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106:djt369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Maleszewska M, Moonen J‐RA, Huijkman N et al. IL‐1b and TGFb2 synergistically induce endothelial to mesenchymal transition in an NFkB‐dependent manner. Immunobiology 2013; 218:443–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Verma A, Artham S, Somanath PR. ALK‐1 to ALK‐5 ratio dictated by the Akt1‐β‐catenin pathway regulates TGFβ‐induced endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition. Gene 2020; 4:145293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mercado‐Pimentel ME, Runyan RB. Multiple transforming growth factor‐b isoforms and receptors function during epithelial‐mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Cells Tissues Organs 2007; 185:146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sobierajska K, Wawro ME, Ciszewski WM, Niewiarowska J. Transforming growth factor‐β receptor internalization via caveolae is regulated by tubulin‐β2 and tubulin‐β3 during endothelial‐mesenchymal transition. Am J Pathol 2019; 189:2531–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Boezio GLM, Bensimon‐Brito A, Piesker J et al. Endothelial TGF‐β signaling instructs smooth muscle cell development in the cardiac outflow tract. eLife 2020; 9:e57603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Li Z, Jimenez SA. Protein kinase Cδ and c‐Abl kinase are required for transforming growth factor β induction of endothelial–mesenchymal transition in vitro . Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:2473–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Rodriguez‐Pascual F, Busnadiego O, Gonzalez‐Santamaria J. The profibrotic role of endothelin‐1: is the door still open for the treatment of fibrotic diseases? Life Sci 2013; 18:156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Arfian N, Suzuki Y, Hartopo AB et al. Endothelin converting enzyme‐1 (ECE‐1) deletion in association with endothelin‐1 downregulation ameliorates kidney fibrosis in mice. Life Sci 2020; 258:118223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lagares D, García‐Fernández RA, Jiménez CL et al. Endothelin 1 contributes to the effect of transforming growth factor beta1 on wound repair and skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62:878–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lambers C, Roth M, Zhong J et al. The interaction of endothelin‐1 and TGF‐β1 mediates vascular cell remodeling. PLoS One 2013; 8:e73399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ahmedat AS, Warnken M, Seemann WK et al. Pro‐fibrotic processes in human lung fibroblasts are driven by an autocrine/paracrine endothelinergic system. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 168:471–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Shi‐wen XU, Denton CP, Holmes AM et al. Fibroblast matrix gene expression and connective tissue remodeling: role of endothelin‐1. J Invest Dermatol 2001; 116:417–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Soldano S, Montagna P, Villaggio B et al. Endothelin and sex hormones modulate the fibronectin synthesis by cultured human skin scleroderma fibroblasts. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68:599–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wei J, Fang F, Lam AP et al. Wnt/β‐catenin signalling is hyperactivated in systemic sclerosis and induces Smad dependent fibrotic responses in mesenchymal cells. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:2734–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Beyer C, Schramm A, Akhmetshina A et al. Beta‐catenin is a central mediator of pro‐fibrotic Wnt signaling in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lam AP, Herazo‐Maya JD, Sennello JA et al. Wnt coreceptor Lrp5 is a driver of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190:185–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Akhmetshina A, Palumbo K, Dees C et al. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF‐β‐ mediated fibrosis. Nat Commun 2012; 3:735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lee WJ, Park JH, Shin JU et al. Endothelial‐to mesenchymal transition induced by Wnt 3a in keloid pathogenesis. Wound Repair Regen 2015; 23:435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Xu D, Mu R, Wei X. The roles of IL‐1 family cytokines in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Front Immunol 2019; 3:2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Montorfano I, Becerra A, Cerro R et al. Oxidative stress mediates the conversion of endothelial cells into myofibroblasts via a TGF‐β1 and TGF‐β2‐dependent pathway. Lab Invest 2014; 94:1068–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Cheng S‐L, Shao J‐S, Behrmann A et al. Dkk1 and MSX2‐Wnt7b signaling reciprocally regulate the endothelial‐mesenchymal transition in aortic endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33:1679–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pérez L, Muñoz‐Durango N, Riedel CA et al. Endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition: cytokine‐mediated pathways that determine endothelial fibrosis under inflammatory conditions. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2017; 33:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wei X‐M, Wumaier G, Zhu N et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase L1 represses endothelial‐mesenchymal transition by inhibiting IL‐1β/NF‐κB/Snail signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2020; 41:1102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hasegawa M, Fujimoto M, Kikuchi K. Elevated serum tumor necrosis factor‐alpha levels in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with pulmonary fibrosis. J Rheumatol 1997; 24:663–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Fujita M, Shannon J. Irvin C et al. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha produces an increase in lung volumes and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cel Mol Physiol 2001; 280:L39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Mahler GJ, Farrar EJ, Butcher JT. Inflammatory cytokines promote mesenchymal transformation in embryonic and adult valve endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33:121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Chakraborty S, Zawieja DC, Davis MJ et al. MicroRNA signature of inflamed lymphatic endothelium and role of miR‐9 in lymphangiogenesis and inflammation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2015; 309:C680–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Yoshimatsu Y, Wakabayashi I, Kimuro S et al. TNF‐α enhances TGF‐β‐induced endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition via TGF‐β signal augmentation. Cancer Sci 2020; 111:2385–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Chrobak I, Lenna S, Stawski L et al. Interferon‐γ promotes vascular remodeling in human microvascular endothelial cells by upregulating endothelin (ET)‐1 and transforming growth factor (TGF) β2. J Cell Physiol 2013; 228:1774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Saigusa R, Asano Y, Taniguchi T et al. Multifaceted contribution of the TLR4‐activated IRF5 transcription factor in systemic sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:15136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Di Benedetto P, Panzera N, Cipriani P et al. Mesenchymal stem cells of systemic sclerosis patients, derived from different sources, show a profibrotic microRNA profiling. Sci Rep 2019; 9:7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Nelson P, Kiriakidou M, Sharma A et al. The microRNA world: small is mighty. Trends Biochem Sci 2003; 28:534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Miscianinov V, Martello A, Rose L et al. MicroRNA‐148b targets the TGF‐beta pathway to regulate angiogenesis and endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition during skin wound healing. Mol Ther 2018; 26:1996–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Katsura A, Suzuki HI, Ueno T et al. Micro RNA‐31 is a positive modulator of endothelial–mesenchymal transition and associated secretory phenotype induced by TGF‐β. Genes Cells 2016; 21:99–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Li L, Kim I‐K, Chiasson V et al. NF‐kB mediated miR‐130a modulation in lung microvascular cell remodeling: implication in pulmonary hypertension. Exp Cell Res 2017; 359:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Henry TW, Mendoza FA, Jimenez SA. Role of microRNA in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis tissue fibrosis and vasculopathy. Autoimmun Rev 2019; 18:102396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Berindan‐Neagoe I, Monroig PDC, Pasculli B et al. MicroRNAome genome: a treasure for cancer diagnosis and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64:311–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Philippen LE, Dirkx E, Wit JBM et al. Antisense MicroRNA therapeutics in cardiovascular disease: quo vadis? Mol Ther 2015; 23:1810–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Hanna J, Hossain GS, Kocerha J. The potential for microRNA therapeutics and clinical research. Front Genet 2019; 10:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Mercatelli N, Coppola V, Bonci D et al. The inhibition of the highly expressed miR‐221 and miR‐222 impairs the growth of prostate carcinoma xenografts in mice. PLOS ONE 2008; 3:e4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Chen Y, Gao DY, Huang L. In vivo delivery of miRNAs for cancer therapy: challenges and strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015; 81:128–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Liu T, Zou X‐Z, Huang N et al. Down‐regulation of miR‐204 attenuates endothelial–mesenchymal transition by enhancing autophagy in hypoxia‐induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Pharmacol 2019; 863:172673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Chen D, Zhang C, Chen J et al. MiRNA‐200c‐3p promotes endothelial to mesenchymal transition and neointimal hyperplasia in artery bypass grafts. J Pathol 2020; 30:209–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Zhao H, Wang Y, Zhang X et al. miR‐181b‐5p inhibits endothelial‐mesenchymal transition in monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by targeting endocan and TGFBR1. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2020; 386:114827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Zhong CM, Li S, Wang XW et al. MicroRNA‐92a‐mediated endothelial to mesenchymal transition controls vein graft neointimal lesion formation. Exp Cell Res 2021; 398:112402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Jiang F, Liu G‐S, Dusting GJ et al. NADPH oxidase‐dependent redox signaling in TGF‐b‐mediated fibrotic responses. Redox Biol 2014; 2:267–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Hecker L, Vittal R, Jones T et al. NADPH oxidase‐4 mediates myofibroblast activation and fibrogenic responses to lung injury. Nat Med 2009; 15:1077–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Jarman ER, Khambata VS, Cope C et al. An inhibitor of NADPH oxidase‐4 attenuates established pulmonary fibrosis in a rodent disease model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013; 50:158–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Kokot A, Sindrilaru A, Schiller M et al. Alpha‐melanocyte‐stimulating hormone suppresses bleomycin induced collagen synthesis and reduces tissue fibrosis in a mouse model of scleroderma: melanocortin peptides as a novel treatment strategy for scleroderma? Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60:592–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Hagiwara SI, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Aerosolized administration of N‐acetylcysteine attenuates lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162:225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Serrano‐Mollar A, Closa D, Prats N et al. In vivo antioxidant treatment protects against bleomycin induced lung damage in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2003; 138:1037–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Chen Y, Yuan T, Zhang H et al. Activation of Nrf2 attenuates pulmonary vascular remodeling via inhibiting endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition: an insight from a plant polyphenol. Int J Biol Sci 2017; 13:1067–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Suzuki T, Carrier EJ, Talati MH et al. Isolation and characterization of endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition cells in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2018; 314:L118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Choi SH, Hong ZY, Nam JK et al. A Hypoxia‐induced vascular endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in development of radiation‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21:3716–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Tang H, Babicheva A, McDermott KM et al. Endothelial HIF‐2alpha contributes to severe pulmonary hypertension due to endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2018; 314:L256–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Hung SP, Yang MH, Tseng KF et al. Hypoxia‐induced secretion of TGF‐beta1 in mesenchymal stem cell promotes breast cancer cell progression. Cell Transplant 2013; 22:1869–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Xu X, Tan X, Tampe B et al. Snail is a direct target of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha (HIF1alpha) in hypoxia‐induced endothelial to mesenchymal transition of human coronary endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:16653–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Mammoto T, Muyleart M, Konduri GG et al. Twist1 in hypoxia‐induced pulmonary hypertension through transforming growth factor‐beta‐smad signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018; 58:194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Capelli C, Zaccara E, Cipriani P et al. Phenotypical and functional characteristics of in vitro‐expanded adipose‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells from patients with systematic sclerosis. Cell Transplant 2017; 26:841–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Liu C, Zhou X, Lu J. Lu J et al. Autophagy mediates 2‐methoxyestradiol‐inhibited scleroderma collagen synthesis and endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition induced by hypoxia. Rheumatology 2019; 58:1966–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Fleming JN, Nash RA, McLeod DO et al. Capillary regeneration in scleroderma: stem cell therapy reverses phenotype? PLOS ONE 2008; 16:e1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Wigley FM. Vascular disease in scleroderma. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2009; 36:150–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Saketkoo LA, Distler O. Is there evidence for vasculitis in systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012; 14:516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Di Benedetto P, Guggino G, Manzi G et al. Interleukin‐32 in systemic sclerosis, a potential new biomarker for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Res Ther 2020; 22:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Derrett‐Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane A et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth factor b‐dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65:2928e2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Good RB, Gilbane AJ, Trinder SL et al. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition contributes to endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Pathol 2015; 185:1850–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Mendoza FA, Piera‐Velazquez S, Farber JL et al. Endothelial cells expressing endothelial and mesenchymal cell gene products in lung tissue from patients with systemic sclerosis‐associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68:210–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Jimenez SA, Piera‐Velazquez S. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis‐associated pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Myth or reality? Matrix Biol 2016; 51:26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Taniguchi T, Asano Y, Akamata K et al. Fibrosis, vascular activation, and immune abnormalities resembling systemic sclerosis in bleomycin‐treated Fli‐1‐haploin‐sufficient mice. Arthritis Rheum 2014; 67:517–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Nakamura K, Taniguchi T, Hirabayashi M et al. Altered properties of endothelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells underlying the development of scleroderma‐like vasculopathy in KLF5+/–;Fli‐1+/– mice. Arthritis Rheum 2020; 72:2136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Andersen GN, Caidahl K, Kazzam E et al. Correlation between increate nitric oxide production and markers of endothelial activation in systemic sclerosis: findings with the soluble adhesion molecole E‐selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and vascular adhesion molecule 1. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43:1085–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Kuryliszyn‐Moskal A, Klimiuk PA, Sierakowski S. Soluble adhesion molecules (sVCAM‐1, sE‐selectin), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and endothelin‐1 in patients with systemic sclerosis: relationship to organ systemic involvement. Clin Rheum 2005; 24:111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Trojanowska M. Cellular and molecular aspects of vascular dysfunction in systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6:453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Giordano N, Papakostas P, Pecetti G et al. Cytokine modulation by endothelin‐1 and possible therapeutic implications in systemic sclerosis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2011; 25:487–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Rincon M. Interleukin‐6: from an inflammatory marker to a target for inflammatory diseases. Trends Immunol 2012; 33:571–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Marden G, Wan Q, Wilks J et al. The role of the oncostatin M/OSM receptor β axis in activating dermal microvascular endothelial cells in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2020; 22:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Liang M, Lv J, Jiang Z et al. Promotion of myofibroblast differentiation and tissue fibrosis by the leukotriene B4‐leukotriene B4 receptor axis in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2020; 72:1013–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Chia JJ, Lu TT. Update on macrophages and innate immunity in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015; 27:530–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:762–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity 2005; 23:344–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P, Vadasz Z et al. Macrophages with regulatory functions, a possible new therapeutic perspective in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2019; 18:102369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Dowson C, Simpson N, Duffy L et al. Innate immunity in systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017; 19:2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Higashi‐Kuwata N, Jinnin M, Makino T et al. Characterization of monocyte/macrophage subsets in the skin and peripheral blood derived from patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12:R128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Stifano G, Christmann RB. Macrophage involvement in systemic sclerosis: do we need more evidence? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18:2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Zordan P, Rigamonti E, Freudenberg K et al. Macrophages commit postnatal endothelium‐derived progenitors to angiogenesis and restrict endothelial to mesenchymal transition during muscle regeneration. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5:e1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Nicolosi PA, Tombetti E, Giovenzana A et al. Macrophages guard endothelial lineage by hindering endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition: implications for the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. J Immunol 2019; 203:247–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Jiang Y, Hu F, Li Q et al. Tanshinone IIA ameliorates the bleomycin‐induced endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition via the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway in a murine model of systemic sclerosis. Int Immunopharmacol 2019; 77:105968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Zhang W, Chen G, Ren J‐G et al. Bleomycin induces endothelial mesenchymal transition through activation of mTOR pathway: a possible mechanism contributing to the sclerotherapy of venous malformations. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 170:1210–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]